As icons of Australian music go, Jimmy Barnes, Peter Garrett and Michael Hutchence – along with the respective bands they fronted, Cold Chisel, Midnight Oil and INXS – are about as iconic as you can get. They are among the most recognisable and renowned names in the annals of Australian music history, not to mention the global cultural landscape, and are emblematic of an era of mega-selling chart success for Australian rock around the world. Each, alongside the incredibly successful Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986), also helped give the country something of a singular, defining identity as a land of untamed masculinity.

These artists emerged out of the societal upheaval of the 1970s, in a country that was beginning to reckon with the part it played in the global market, its responsibilities within the region in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the effects of industrialisation on the environment. This was a time when the rights of Indigenous peoples were finally being institutionalised, and when multiculturalism was challenging the very meaning of the term ‘Australian’. The genre – labelled ‘pub rock’ – was a stiff middle finger to the rise of colourful and outrageous disco music and the more slickly polished American style of rock’n’roll. It was – depending on how you perceive it – an enclave for the working class alienated by the changing nation wherein ‘[t]he Woodstock spirit of peace and love and bad brown acid was largely replaced […] by VB, Tooheys and West End’.[1]James Cockington, Long Way to the Top: Stories of Australian Rock & Roll, ABC Books, Sydney, 2001, pp. 141–52.

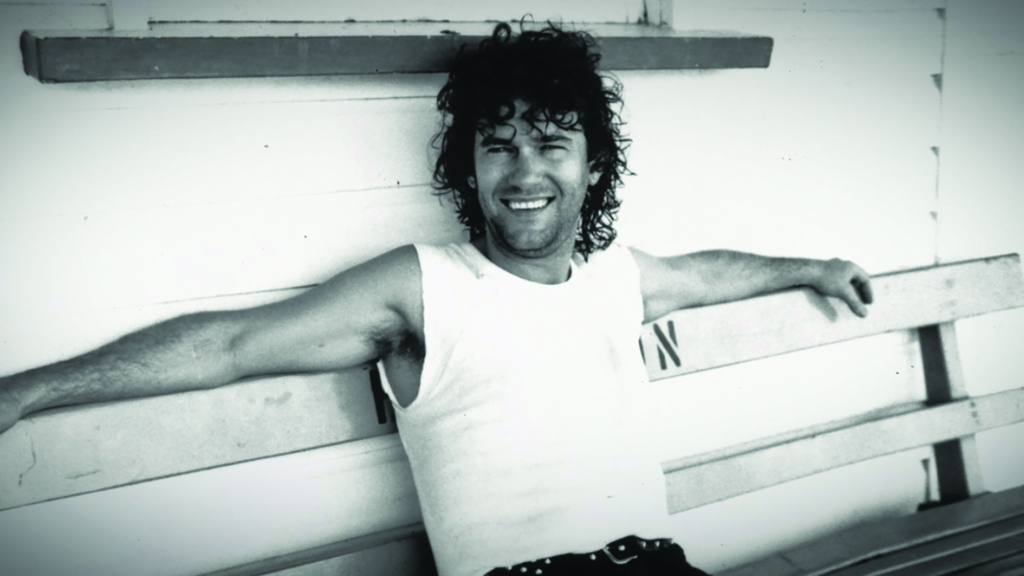

Despite Barnes and Garrett being vocal advocates for left-leaning politics, they remained beloved within this musical scene that has been critiqued for its ‘localism and hyper-masculine attitude’.[2]Vincent Dwyer, ‘From Cold Chisel to Craft Beer: The Gentrification of Pub Rock’, VICE, 25 September 2017, <https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/43axyb/from-cold-chisel-to-craft-beer-the-gentrification-of-pub-rock>, accessed 15 August 2019. And, while Hutchence, the brooding voice of INXS whose sex appeal was almost as large as his vocal talent, never ventured far into the world of politics, his excursions into the unconventional – including collaborations with queer artist Troy Davies and a relationship with pop star Kylie Minogue, not to mention his sensitive, James Dean–like persona – suggested a man who was concerned less with pub rock’s macho world than with the Europeanised world of, say, fellow Australian rock star Nick Cave.

The three musicians – and their complex relationship with the musical milieu in which they rose to prominence – thus make for ideal documentary subjects. And it says a lot about the creativity within the local nonfiction-filmmaking scene that the three recent works about them have opted for wildly different approaches: presenting live first-person testimonials, digging into archives and unearthing an unexamined chapter in the public life of its subject, respectively. But Australia has a long and extensive musical history, and the main limitation of what is essentially a boutique industry like ours is that, seemingly, only names as big as Barnes or Hutchence merit the investment of substantial film production. Naturally, one can hardly expect the local industry to cover our cavalcade of pop stars, Triple J indie sensations and one-album wonders with as much gusto and investment as these world-famous pub-rock stalwarts. At the same time, wider segments of the Australian music industry do also deserve critical attention.

Bared soul: Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Boy

Mark Joffe’s Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Boy (2018) is a retelling of its titular musician’s 2016 memoir.[3]Jimmy Barnes, Working Class Boy, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2016. Throughout stretches of the film, Barnes stands on a relatively sparse stage, detailing his life as the son of Scottish immigrants and his journey to Australian music stardom. His recollections are interspersed with live solo performances and footage of Barnes visiting locations from his youth, including the streets of Glasgow and the suburbs of Adelaide.

Joffe – known for having directed Cosi (1996), The Man Who Sued God (2001) and several works for television – handles the material deftly. The musical acts are elegantly staged, although fairweather fans will likely feel short-changed by the absence of many of Cold Chisel’s more significant hits, with the burden of familiarity falling predominantly on the shoulders of the sublimely performed ‘Flame Trees’ and ‘When the War Is Over’.

While Barnes speaks poetically, it’s often to mixed effect – as though he’s reading directly from the pages of his memoir. (Indeed, at times, he does: ‘Glasgow still evokes mixed emotions in me,’ he narrates over black-and-white footage. ‘Looking out the window on a Saturday night and being amazed at the scene on the street below at closing time. Singing, fighting, kissing and hustling, and that was just one couple. My mum and dad.’[4]Minimally edited extract from ibid.) More impressive is when he reflects, with refreshing candour, on the abuse he suffered at the hands of his parents, both of whom struggled to adapt to life away from Scotland. His openness is significant, given how much men have faced difficulties over the years being forthcoming about the emotional and physical troubles they have experienced – consider how momentous it was for Australian Rules football player Mitch Clark to deal with his mental-health struggles so publicly in 2015,[5]See Jessica Leahy, ‘AFL Player Mitch Clark Bravely Addresses His Battle with Depression’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 11 May 2015, available at <https://www.nowtolove.com.au/health/diet-nutrition/afl-player-mitch-clark-bravely-addresses-his-battle-with-depression-12748>, accessed 19 August 2019. and for peers Majak Daw, Dayne Beams and Adam Treloar to subsequently traverse a similar path.[6]See Jake Niall, ‘Daw Incident May Reduce Cynicism over Footballers’ Mental Health’, The Age, 19 December 2018, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/afl/daw-incident-may-reduce-cynicism-over-footballers-mental-health-20181219-p50nav.html>; Sam McClure & Jake Niall, ‘Magpies’ Beams Takes Indefinite AFL Break, Quaynor to Debut’, The Age, 3 July 2019, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/afl/magpies-beams-takes-indefinite-afl-break-quaynor-to-debut-20190703-p523qm.html>; and ‘Collingwood Star Adam Treloar Opens Up on Battling Anxiety’, News.com.au, 6 August 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/sport/afl/collingwood-star-adam-treloar-opens-up-on-battling-anxiety/news-story/3ebebe26e3173c1f17b6ada2d1e04d49>, all accessed 14 August 2019.

The main problem with Working Class Boy is that it cuts its own story short … It’s a shame that Joffe allows Barnes to bravely broach the subject of patriarchal abuse without then interrogating the relationship that his own music has to a culture of chauvinism and machismo.

The main problem with Working Class Boy is that it cuts its own story short. Barnes’ later material veered away from the sweaty, beer-soaked masculine mythologising of iconic songs like ‘Working Class Man’ and ‘Khe Sanh’; in recent years, he has been outspoken against right-wing politics and the insidious ways in which his music from that pub-rock era has been appropriated by the likes of Liberal Party politician Josh Frydenberg[7]See Riley Morgan, ‘“You Don’t Represent Me”: Jimmy Barnes Slams Frydenberg over Song Reference’, SBS News, 3 May 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/you-don-t-represent-me-jimmy-barnes-slams-frydenberg-over-song-reference>, accessed 15 August 2019. and alt-right hate groups such as Reclaim Australia.[8]See Tom Williams, ‘Jimmy Barnes Speaks Out Against Reclaim Australia for Using Cold Chisel Music’, Music Feeds, 21 July 2015, <https://musicfeeds.com.au/news/jimmy-barnes-speaks-out-against-reclaim-australia-for-using-cold-chisel-music/>, accessed 15 August 2019. It’s a shame that Joffe allows Barnes to bravely broach the subject of patriarchal abuse without then interrogating the relationship that his own music has to a culture of chauvinism and machismo.

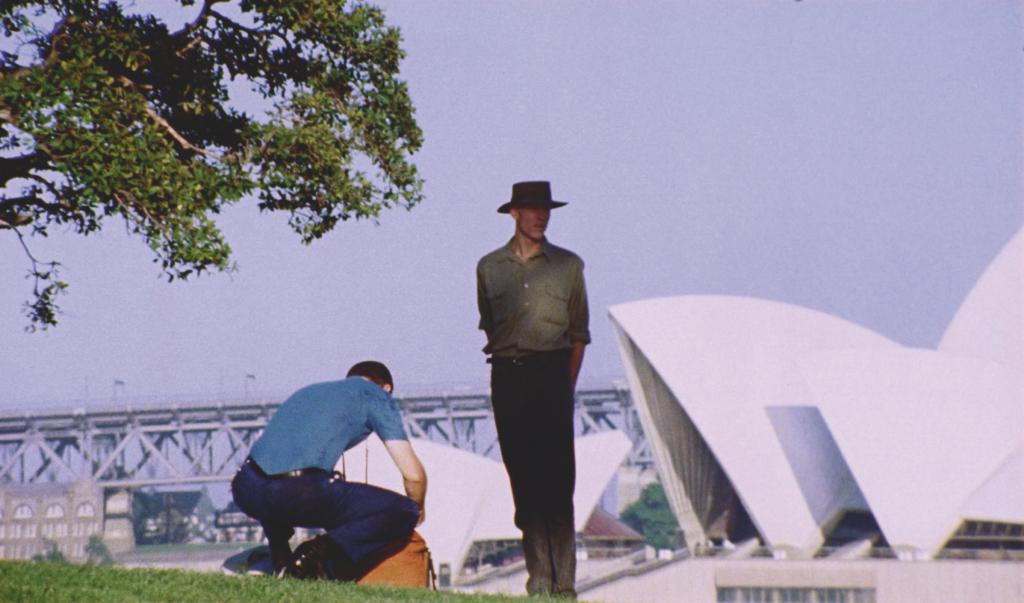

Past anew: Midnight Oil: 1984

Overall more successful – though not without its own deficiencies – is Midnight Oil: 1984 (2018), a compilation of previously unseen archival footage shot by its award-winning director, Ray Argall, whose portfolio includes music videos for Split Enz, Crowded House and Hoodoo Gurus. Set against the release of the titular band’s album Red Sails in the Sunset and Garrett’s ascent as an environmental activist and political force, Midnight Oil: 1984 is an impressive exercise in vault-diving. It boasts a wealth of remarkable on- and offstage footage, and defining its period of documentation so strictly – little context is offered regarding either side of the titular year – means that Argall, also acting as his own editor, avoids having to pad out his film with needless talking heads and a Wikipedia approach to history.

This does mean, however, that Argall’s film doesn’t deeply explore Garrett’s or Midnight Oil’s place in the broader story of land-rights struggles, environmentalism and anti-nuclear activism in Australia, which is arguably the more interesting angle for a movie about the band and its infectious lead from a 2019 viewer’s perspective. Decades before these topics became political hot potatoes – An Inconvenient Truth (Davis Guggenheim, 2006) would not come out for another twenty-two years – the band were selling their ‘green’ message to enthusiastic, enraptured crowds of all ages across the world. Certainly, I was taken by the film’s wonderfully evocative home-movie aesthetic of pockmarked celluloid and its immensely satisfying soundtrack of killer songs. But, despite the intentional limitation of its scope, I would have relished the chance to learn more about the band’s legacy – particularly as some of their then-budding-environmentalist fans will now have risen up the societal ranks.

Untold story: Mystify: Michael Hutchence

The most affecting of the three documentaries is Mystify: Michael Hutchence (Richard Lowenstein, 2019), which adopts an unconventional tack in telling the story of the late INXS frontman. Unlike most films of this variety, which opt for a birth-to-death trajectory, Lowenstein has chosen to concentrate on the years leading up to Hutchence’s tragic death, which many still believe was the result of a sexual mishap[9]See ‘Paula Challenges Hutchence Verdict’, BBC News, 10 August 1999, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/416509.stm>, accessed 14 August 2019. but, as Mystify suggests, was a suicide resulting from years of living with a chronic brain injury following an assault in Copenhagen.

The film’s focus on this specific arc means that swathes of Hutchence’s and INXS’s career go unrecognised. My personal favourite INXS album, 1982’s Shabooh Shoobah, doesn’t get a single mention, while more personal elements of Hutchence’s life – such as synth-pop side project Max Q – feature prominently. Despite this, there’s no sense that Mystify is missing something biographically essential. Instead, it seems to get closer to the truth of its central figure than what audiences are offered by either Working Class Boy or Midnight Oil: 1984.

This is helped by the fact that Lowenstein is a sort of cinematic father-figure for the Australian rock scene, having previously directed the rock docs Australian Made: The Movie (1987, also featuring Barnes), We’re Livin’ on Dog Food (2009), Autoluminescent: Rowland S. Howard (co-directed with Lynn-Maree Milburn, 2011) and Ecco Homo (co-directed with Milburn, 2015) as well as some of INXS’s most notable videos, including ‘Never Tear Us Apart’ and ‘Need You Tonight’. Lowenstein’s intimate relationship with Hutchence and those who knew him best have allowed him to dig more deeply with his interviewees, get more personal with the delicate archival material and, ultimately, deliver a story with greater weight. As critic Anthony Morris puts it in his ArtsHub review of the film: ‘A good biography gives you the facts; a great one gives them a life.’[10]Anthony Morris, ‘Film Review: Mystify – Michael Hutchence’, ArtsHub, 4 July 2019, <https://www.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/film/anthony-morris/film-review-mystify-michael-hutchence-258328>, accessed 15 August 2019.

Counterpoints: Gurrumul and others

Gurrumul (Paul Damien Williams, 2017) stands as something of an outlier – and, perhaps, a sort of course correction – as it puts the life story of award-winning, platinum-selling Yolngu musician Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu under the spotlight. It’s a refreshing change of pace to see a film about somebody whose musical legacy is more than a single degree of separation from the rest.

Through evocative and atmospheric cinematography as well as impressive sound design, Williams’ film presents a classic ‘year in the life’–style narrative documenting the singer/songwriter’s travails on the road and the time he spends at home on Elcho Island. Of course, considering it premiered shortly after the singer’s death, Gurrumul plays as more of a tribute than may have been intended. Perhaps because of this – or, otherwise, out of a lack of desire to engage in interrogation – the film’s exploration of Yunupingu’s career is divorced from the industry surrounding it. Ours is a music scene that, for instance, oddly relegates those who sing in Indigenous Australian languages to the ‘World Music’ category of its own national awards (the ARIAs),[11]See ‘Best World Music Album’, ‘Winners by Award’, ARIA Awards website, <https://www.ariaawards.com.au/history/award/best-world-music-album>, accessed 14 August 2019. in a case of simultaneous ‘owning’ and Othering. And, while the film packs as much of an emotional punch as Gurrumul’s music, it’s almost as if it needed someone like Garrett to swing by and cause a bit of a ruckus to whip it out of its more traditional storytelling beats.

Still, Gurrumul presents audiences with a story that they normally might not encounter; for that alone, it is already an achievement. In industry terms, the film is also notable for its scale and reach, particularly when compared to earlier work profiling Aboriginal luminaries – Best Kept Secret (Richard Reisz, 1991) on Archie Roach; Tribal Voice (Stephen Michael Johnson, 1993) on Yothu Yindi; Jimmy Little’s Gentle Journey (Sean Kennedy, 2003) on Jimmy Little; and The Black Fella White Fella Tour (Rob Stewart, 1987) on Warumpi Band as well as Big Name No Blanket (Steven McGregor, 2013) on its frontman, George Burrarrawanga.

Outside of the pub-rock fold, other seminal Australian performers have enjoyed attention on screen, but not recently – including the titular subjects of John Farnham: 25th Anniversary Celebration (Ed St John & David Wilson, 1992) and The Slim Dusty Movie (Stewart, 1984). The Go-Betweens: Right Here (Kriv Stenders, 2017) did give viewers a lively silver-screen account of its eponymous band, but The Easybeats only got a made-for-TV miniseries with all the usual tropes, the ABC’s 2017 Friday on My Mind, while The Seekers enjoyed a mere Australian Story instalment – 2019’s ‘A World of Their Own’ – also for the ABC. Even Olivia Newton-John has only managed to be the unfortunate recipient of a Seven Network two-parter, 2018’s Olivia Newton-John: Hopelessly Devoted to You; with its seemingly low-budget re-creations and cheap sentimentality, the Delta Goodrem–headlined biopic received savage reviews.[12]See ‘“This Is a True Trainwreck”: Viewers Slam Delta Goodrem in New Olivia Newton-John Biopic’, The Music, 14 May 2018, <https://themusic.com.au/article/l8uIi4qNjI8/this-is-a-true-trainwreck-viewers-slam-delta-goodrem-in-new-olivia-newton-john-biopic/>, accessed 14 August 2019.

Strangely, Australian musicians’ concerts and tours rarely get the cinematic treatment – Savage Garden: Superstars and Cannonballs (Mark Adamson & Pip Mattiske, 2000) comes to mind as a rare example. While American pop behemoths Taylor Swift and Beyoncé have recently had their respective tour documentaries premiere on Netflix, the streaming service could easily up its quota of local content by commissioning films trailing Aussie stars who’ve made it big here and overseas, like Jessica Mauboy, 5 Seconds of Summer or The Veronicas. I was glad, though, to see Lowenstein’s Australian Made receive the remastering treatment in 2016,[13]See ‘Australian Made Celebrates 30 Years with Remaster’, Mediaweek, 31 October 2016, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/australian-made-30-years/>, accessed 19 August 2019. which at least put a small spotlight on the female-fronted bands Divinyls and I’m Talking.

Shockingly, Kylie Minogue – arguably this country’s most successful international musical export – had her behind-the-tour documentary White Diamond: A Personal Portrait of Kylie Minogue (William Baker, 2007) receive mere one-night-only screenings before being sent to DVD. The filmed 3D version of her acclaimed Aphrodite: Les Folies Tour, aired as a TV special four years later, was met with a similarly restrictive release window. An illegal full upload of the latter has racked up close to 2 million views on YouTube; I dare say streaming providers had best begin talks with Minogue.

From our current vantage point, it does seem that the tide is turning away from giving the same old suspects big-screen prominence. I Am Woman (Unjoo Moon, 2019), a biopic about the life of singer/activist Helen Reddy (to be played by Tilda Cobham-Hervey), recently premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. Before that, the Melbourne International Film Festival unveiled Suzi Q (Liam Firmager, 2019), a documentary about musician and regular music-doco talking head Suzi Quatro. And waiting in the wings is Chrissy Amphlett: Lay My Body Down (Milburn), which, at the time of writing, is in production. Elsewhere, super-indie documentaries like Her Sound, Her Story (Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore, 2018), Now Sound: Melbourne’s Listening (Tobias Willis, 2018) and No Time for Quiet (Hylton Shaw & Samantha Dinning, 2019) have, in their own ways, shone a spotlight on the gendered power imbalances within Australia’s music scene.

*

Biographical films about musicians have the ability to explore not just the lives of their subjects, but also how attitudes reflected and reinforced by popular music at the time mutate and exert influence on the contemporary cultural landscape. Hyper-masculine attitudes are as potent today, for instance, as they were in the pub-rock days because we continue to mythologise (accurately or otherwise) the figureheads of that era. But there is room for diversity and growth – and, if the newer titles gracing our screens are anything to go by, perhaps audiences will one day have a more heterogeneous range of musical heroes to wax nostalgic about.

Endnotes

| 1 | James Cockington, Long Way to the Top: Stories of Australian Rock & Roll, ABC Books, Sydney, 2001, pp. 141–52. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Vincent Dwyer, ‘From Cold Chisel to Craft Beer: The Gentrification of Pub Rock’, VICE, 25 September 2017, <https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/43axyb/from-cold-chisel-to-craft-beer-the-gentrification-of-pub-rock>, accessed 15 August 2019. |

| 3 | Jimmy Barnes, Working Class Boy, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2016. |

| 4 | Minimally edited extract from ibid. |

| 5 | See Jessica Leahy, ‘AFL Player Mitch Clark Bravely Addresses His Battle with Depression’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 11 May 2015, available at <https://www.nowtolove.com.au/health/diet-nutrition/afl-player-mitch-clark-bravely-addresses-his-battle-with-depression-12748>, accessed 19 August 2019. |

| 6 | See Jake Niall, ‘Daw Incident May Reduce Cynicism over Footballers’ Mental Health’, The Age, 19 December 2018, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/afl/daw-incident-may-reduce-cynicism-over-footballers-mental-health-20181219-p50nav.html>; Sam McClure & Jake Niall, ‘Magpies’ Beams Takes Indefinite AFL Break, Quaynor to Debut’, The Age, 3 July 2019, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/afl/magpies-beams-takes-indefinite-afl-break-quaynor-to-debut-20190703-p523qm.html>; and ‘Collingwood Star Adam Treloar Opens Up on Battling Anxiety’, News.com.au, 6 August 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/sport/afl/collingwood-star-adam-treloar-opens-up-on-battling-anxiety/news-story/3ebebe26e3173c1f17b6ada2d1e04d49>, all accessed 14 August 2019. |

| 7 | See Riley Morgan, ‘“You Don’t Represent Me”: Jimmy Barnes Slams Frydenberg over Song Reference’, SBS News, 3 May 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/you-don-t-represent-me-jimmy-barnes-slams-frydenberg-over-song-reference>, accessed 15 August 2019. |

| 8 | See Tom Williams, ‘Jimmy Barnes Speaks Out Against Reclaim Australia for Using Cold Chisel Music’, Music Feeds, 21 July 2015, <https://musicfeeds.com.au/news/jimmy-barnes-speaks-out-against-reclaim-australia-for-using-cold-chisel-music/>, accessed 15 August 2019. |

| 9 | See ‘Paula Challenges Hutchence Verdict’, BBC News, 10 August 1999, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/416509.stm>, accessed 14 August 2019. |

| 10 | Anthony Morris, ‘Film Review: Mystify – Michael Hutchence’, ArtsHub, 4 July 2019, <https://www.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/film/anthony-morris/film-review-mystify-michael-hutchence-258328>, accessed 15 August 2019. |

| 11 | See ‘Best World Music Album’, ‘Winners by Award’, ARIA Awards website, <https://www.ariaawards.com.au/history/award/best-world-music-album>, accessed 14 August 2019. |

| 12 | See ‘“This Is a True Trainwreck”: Viewers Slam Delta Goodrem in New Olivia Newton-John Biopic’, The Music, 14 May 2018, <https://themusic.com.au/article/l8uIi4qNjI8/this-is-a-true-trainwreck-viewers-slam-delta-goodrem-in-new-olivia-newton-john-biopic/>, accessed 14 August 2019. |

| 13 | See ‘Australian Made Celebrates 30 Years with Remaster’, Mediaweek, 31 October 2016, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/australian-made-30-years/>, accessed 19 August 2019. |