In 1897, HG Wells published The Invisible Man, a novel with a relatively simple premise: Griffin, a scientist, has found a way to make himself invisible – but unfortunately doesn’t know how to reverse the process. Stuck in this state, he rapidly discovers that he can act without consequence, and the book – flicking back and forth between the past and the present – tracks his descent into murder and madness.

Since then, the novel has been adapted and reimagined numerous times. James Whale’s 1933 film was mostly faithful to the spirit of the story; 1984 saw a Russian version, directed by Aleksandr Zakharov, that tracked along similar lines; and Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man (2000), despite having a different title and changing its central character’s name to Sebastian Caine (Kevin Bacon), once again followed the familiar formula. Sometimes, the scientist shows a bit of remorse. Others, he fully descends into becoming a monster. His acts, once free of consequence, vary in their obscenity and violence. In some versions, there is a woman, a love interest, and her significance and impact on the plot vary too. The shift in eras allows for directors to play with details, with changing technology providing challenges for villains and heroes alike. Where once the invisible man might only be detectable by footsteps in the snow, perhaps he can now be found using infra-red goggles. In times gone by, he could have only travelled as far as a horse, a train or a boat could take him; in a world filled with cars and planes, however, he can go anywhere, be anywhere, escape more easily. Despite this, the book, Whale’s adaptation and Hollow Man all end in essentially the same way: he dies.

This is all just window-dressing, however. When you pare back all the light and colour, at their core, these narratives are all pretty much the same: stories about a man who becomes irreversibly invisible, and who abuses his newfound power. It would make sense to think that this is the foundation, the skeleton, that any adaptation of The Invisible Man would need to be built outwards from. However, Leigh Whannell has deviated from the well-trodden path. His 2020 eponymously named film, which he both wrote and directed, has an invisible man – but he isn’t the central character.

This iteration of The Invisible Man is the story of a woman. It opens on Cecilia (Elisabeth Moss) escaping in the dead of night from her abusive partner. Having drugged him, she tiptoes her way through the camera-filled house in a stressful flight that climaxes in her only just managing to get into her confused sister’s car as her partner punches the window. It’s terrifying and tense – and also serves as our introduction to Adrian Griffin (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), the brilliant and wealthy optics engineer who would normally be at the centre of the plot. In a way, with the invisible man himself out of the spotlight, this is the first time a version of Wells’ novel has truly lived up to its name.

Whannell tells me that, when he was approached about potentially taking on the project, he was asked, ‘What would be your take on this character?’ He didn’t hesitate: ‘I just blurted out, “Well, I would probably tell the story from the point of view of the victim, you know, the person that the invisible man is hunting,” and that was it.’ It’s an interesting and effective choice – and the end result, despite the different perspective, and big deviations from what audiences have come to expect from an Invisible Man story, nonetheless feels true to the spirit of the original novel.

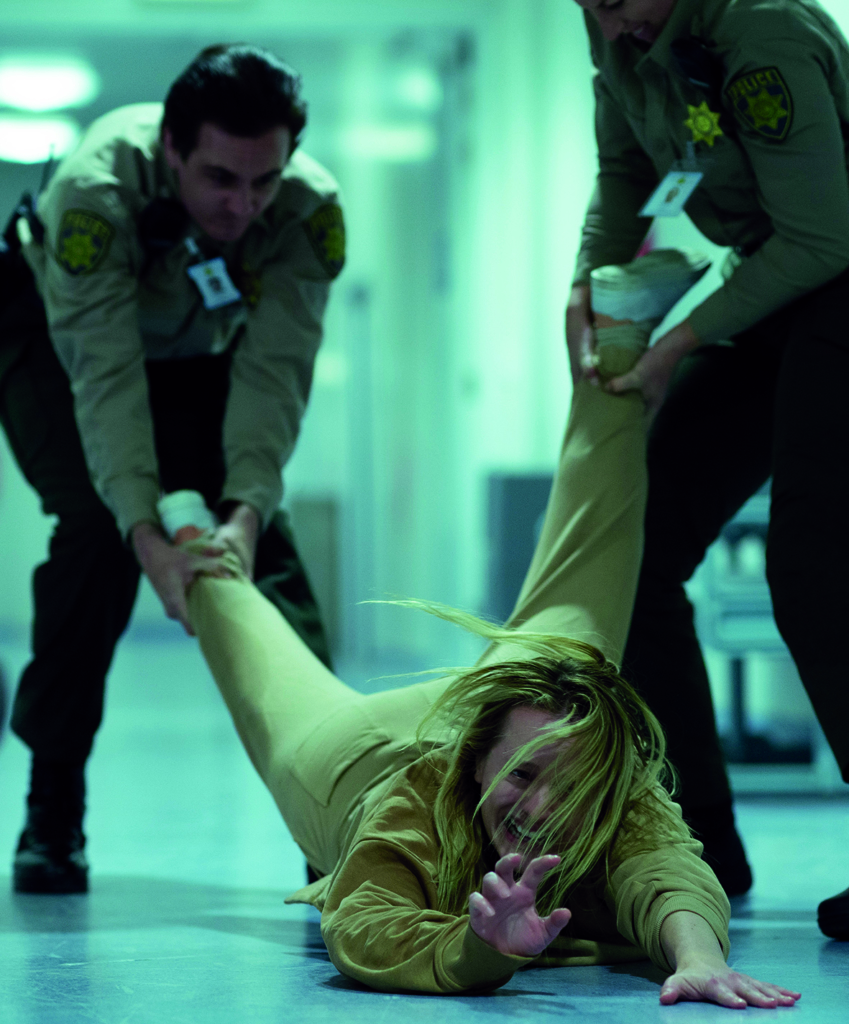

Cecilia moves in with a friend. She is shaken and scared, and can barely leave the house. Then she receives the unexpected news that Adrian has died. She rapidly cycles from shock to relief – and finally feels free, safe. But then, of course, strange things start to happen. She finds the front door open when she is sure that it was closed; senses a presence in her room; goes to pull on her blanket, only to find that it is caught on something, and sees the outline of a shoe holding it down – except there’s no-one there.

The end result, despite the different perspective, and big deviations from what audiences have come to expect from an Invisible Man story, nonetheless feels true to the spirit of the original novel.

Whannell is a deft hand when it comes to depicting horror and psychological torment on screen – he wrote and starred in the now-legendary Saw (James Wan, 2004), and wrote the screenplays for Saw II (Darren Lynn Bousman, 2005), Saw III (Bousman, 2006) and all four Insidious films (2010–2018), a series that tears at the boundary between life and death. He also wrote and directed the science fiction body-horror feature Upgrade (2018). So it’s fitting that The Invisible Man lies at the intersection of these genres. It’s a psychological thriller in which, for a large portion of the film, viewers try to figure out whether there really is an invisible man or whether Cecilia is herself going mad. It’s a horror film, as things descend into murder and mayhem, blood and gore. And it’s science fiction at its best, as Whannell gently pushes at what is both possible and plausible when it comes to making invisibility a reality.

‘Thrillers, science fiction, horror film – they’re all close cousins, so you can kind of dabble in each and take elements,’ Whannell explains.

Alien is basically a horror movie, but it’s also a sci-fi movie, [though] some may say it’s only called a sci-fi movie because there are spaceships in it […] I don’t necessarily like to pin down the genre when I’m writing.

Given the source text’s strong legacy, any adaptation of The Invisible Man comes with certain expectations. Asked if the preceding body of work acted as a millstone on the writing and directing process, Whannell is circumspect: ‘I was hoping to weave that spell on the audience [to] make them forget about any past iterations of this character, and kind of drag it kicking and screaming into the modern era.’ He pauses. ‘I think there’s an interesting amnesia that happens with movie audiences – as soon as the lights go down, they’re just with the character.’

It’s true. Despite the title leading viewers to reasonably expect that the film will, quite literally, feature an invisible man, for a large portion of the movie it’s unclear whether it actually does. The film is richer for this ambiguity; it allows for a deeper insight into Cecilia’s mind and trauma. As she tries to confide her suspicions to those around her, she is dismissed. When it is ultimately confirmed that her tormentor is real, it’s revealed that his invisibility is achieved through a sophisticated suit covered in movable lenses. Here is another big deviation from the other adaptations and source material: in this version, the invisibility is reversible.

Cecilia’s domestic-abuse story is told twice: once, off screen, through the lens of realism; and a second time, through the lens of science fiction and horror.

Whannell puts this choice down to a matter of storytelling and focus:

I feel like if I made a story about someone who is invisible and […] unable to make themselves visible, I would probably have to make that character the central character so that I could unravel their psyche. It would be a character study of them, whereas this film is really a character study of [Cecilia].

The impact of this choice ripples into Cecilia’s characterisation and the story of the domestic abuse inflicted upon her by Adrian. In previous versions of The Invisible Man, forced, permanent invisibility means that there is no hope for him to have a normal life, and it is perhaps this that makes him embrace the worst parts of his nature: whether or not he was a good or bad man before, this is arguably the catalyst for him embracing the path of darkness. In Whannell’s version, the invisible man has a choice every time he puts on the suit – it simply augments the person he already was. He chooses to put on the suit in order to tug at Cecilia’s sanity, to sabotage her relationships. His actions done with the aid of the suit echo the abuse from before: he isolates her, makes her question her own judgement, causes her physical harm. But now, she can’t make anyone believe her. In this way, Cecilia’s domestic-abuse story is told twice: once, off screen, through the lens of realism as she recounts in scant detail why she was fleeing her previous life; and a second time, through the lens of science fiction and horror, which serves to underscore just how unbearable her experience has been.

Cecilia’s story could have been told without the invisibility; the performances and the writing are strong enough that the film doesn’t need a gimmick to hook viewers in. But here, the invisibility isn’t a gimmick at all – it’s a technique used to throw audiences off their guard in how they perceive the experience of a survivor of domestic violence, showing how easily someone can be cut off from their support networks and be made to seem unstable, their story easy to dismiss.

It’s a compelling film, with real-world resonance. But is this an adaptation of Wells’ The Invisible Man, or is it simply a film that takes certain familiar elements and twists them into something entirely new? ‘When I was writing it,’ Whannell explains, ‘I just really forgot about any other past approach to this character, and was like, “I’m just going to use this character as a springboard for a thriller.”’ This response would seem to suggest he falls into the latter camp. Yes, both the novel and the film hinge on a scientist named Griffin figuring out the secret to invisibility. And yes, the Griffins on both the page and the screen use this power to do awful things. But the motives differ. The plot, for the most part, is entirely new. The perspective is different.

So which of these elements matter most? Which of them carry more weight? How far can we push the boundaries of a text? Maybe it isn’t the specific way a story unfolds that makes for a faithful adaptation; perhaps it is more about the core questions the story asks: in this case, what would someone do if they had the power to move through the world unseen? And would the ability to act without consequence be enough to corrupt anyone?

Every version of The Invisible Man has taken these questions on in some way. ‘I felt that human tendency to get away with things really drove the story,’ Whannell says. Whether it is intentional or merely an interesting side effect, an opportunity to explore these questions is opened up by the fact that, in this version, the invisibility is made possible by a suit. In all his previous iterations, Griffin is always the only one with the power to become invisible, and so there is no-one to compare or contrast him with. His experience is the only one from which readers and viewers are able to draw conclusions. Does the invisibility itself drive him to madness? Or was he a malicious person all along, the invisibility simply allowing him to act on his true desires? In Whannell’s film, someone else has the opportunity to put on the suit and do as they please without repercussions. What they ultimately choose to do with this power only adds, if anything, more questions into the mix.

A successful adaptation should not simply repeat the existing narrative for the sake of it; it should revitalise the conversation, offering something new while staying true to the ideals of the original. The Invisible Man, in all its versions, prompts us to think about ourselves and those around us from a different standpoint – because if we always stay in the same place, it becomes easy to stop seeing. As Wells wrote in the original book: ‘Great and strange ideas transcending experience often have less effect upon men and women than smaller, more tangible considerations.’[1]HG Wells, The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance, Edward Arnold, New York, 1897, p. 85.

Endnotes

| 1 | HG Wells, The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance, Edward Arnold, New York, 1897, p. 85. |

|---|