A key strength of Australia’s local game making scenes is the distinct character of the games themselves; while the global connectivity afforded by the internet tends to obstruct the formation of scenes with particular stylistic sensibilities, Australia’s relative geographical isolation has helped produce an environment where people can still make games that stand out. Notably, despite scene-specific trends that influence the popularity of certain types of games being made, obvious clones are rare. What’s particularly striking about a new wave of recent and upcoming Australian releases is their emphasis on narrative content, which speaks to changes in approach for indie game production.

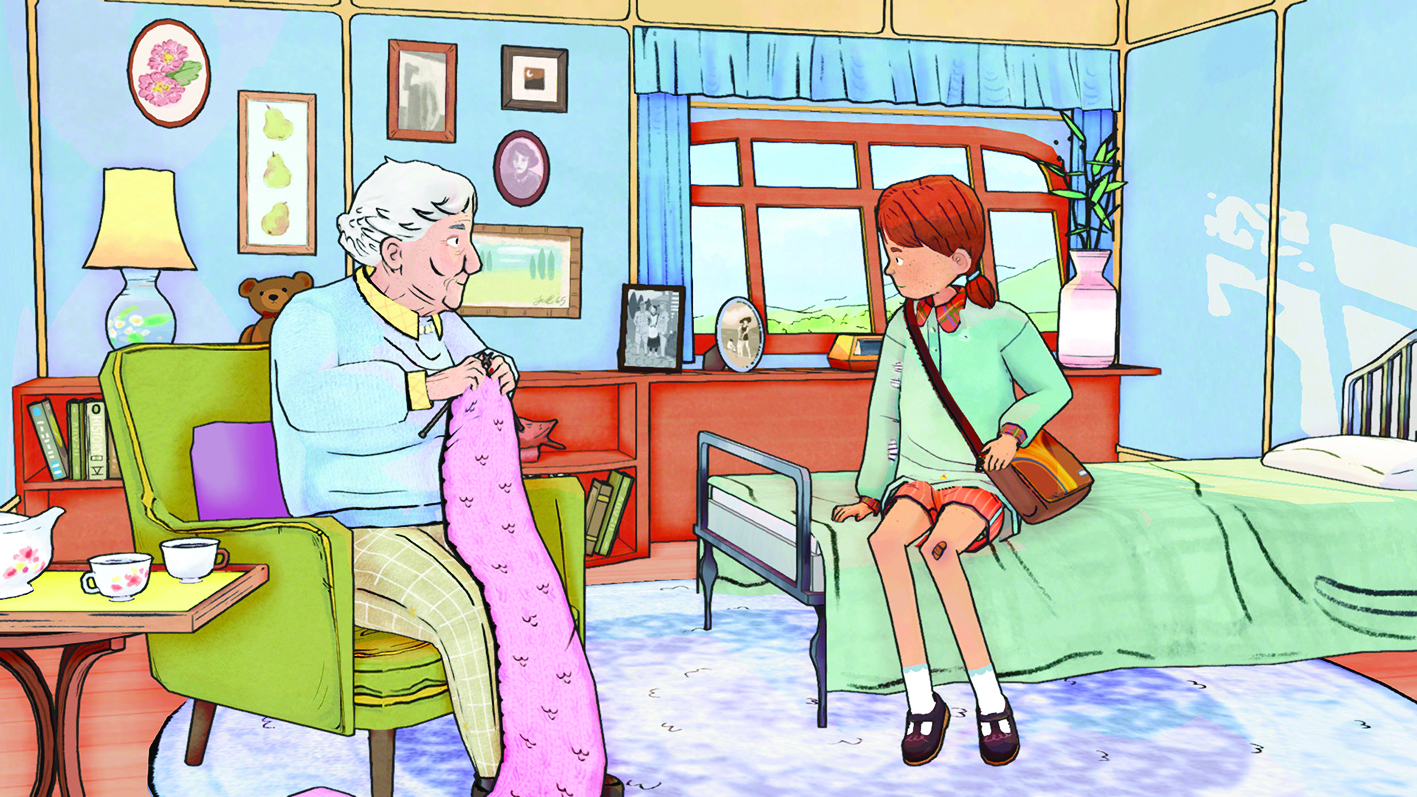

For some of these titles, such as Unpacking, Way to the Woods and Totem Teller, this narrative content is expressed implicitly, deploying environmental storytelling and world-building techniques to convey a sense of place and stimulate player imagination, recalling the design of 2018’s Florence. Other forthcoming games – such as Wayward Strand, Beyond the Veil, Broken Roads and The Forgotten City – also heavily emphasise narrative elements, but do so more explicitly. In particular, these games tend to lean more heavily on direct exposition and incorporate branching dialogue or decision trees that vastly complicate development. Australian narrative-focused titles such as Necrobarista and the Frog Detective series have tended to forgo elaborate branching structures in favour of more linear designs. Tellingly, the most prominent Australian-made game with non-linear elements is arguably L.A. Noire, whose legacy is bound up in its blown-out budget, the gruelling crunch endured by its developers and the studio’s subsequent closure.

Many of these narrative-focused games resemble what videogame scholar Felan Parker has termed ‘boutique indie’: slick and polished mid-budget titles that occupy a middle ground between more experimental indie games, such as New Ice York, and more conventional games produced by the Triple-A industry. Part of these games’ appeal is their disavowal of conventional videogame skill sets, with interaction paradigms that instead more closely resemble the way things work in everyday life. Notably, boutique indie titles made overseas are often backed by established publishers like Annapurna Interactive, Devolver Digital or Humble Games, which can offer financial support while taking responsibility for marketing and other PR-related duties. In contrast, many of the games listed above are self-published – a consequence of state-level game production funding in Australia – indicating that these studios will need to be more resourceful to attain similar profit margins.

The prominence of boutique indie games in Australia reflects a wider trend towards more niche titles that attract a dedicated audience. This represents a clear turn away from the strategy of Defiant Development, for example, whose polished, action-centric Hand of Fate series was generally well received, but still had to compete with much larger Triple-A offerings. Conversely, Triple-A competition for the narrative-focused space is essentially non-existent; indeed, the often intimate stories that these games emphasise are largely at odds with blockbuster games, which instead tend to pull from a common pool of themes likely to appeal to a wider audience – while paradoxically taking pains to avoid any implication that the politics of their virtual worlds have any bearing on our own. Boutique indie games instead tend to lean into the real-world implications of their narrative content. This is not to say that these games attempt to convey a clear ‘message’ for audiences to consume, but rather that developers carry a strong vision of a particular time, place or experience they aim to represent. Creating these games is largely made possible through divestment from more entrenched mainstream game cultures in favour of reaching an equally dedicated niche audience. Of course, this niche appeal carries its own risks – for example, the possibility of critical acclaim without profit.

It is also worth problematising the value proposition of games marketed on the basis of their personal or ‘semi-autobiographical’ content. For many boutique indie studios, the unique value of their games rests partly on their authenticity. Artists put something of themselves into their work as a matter of course, even at the Triple-A level, but there is something different about the ways that the ‘handcrafted’ or ‘bespoke’ qualities of boutique indie titles are deployed as their key selling point. The potential for self-exploitation – in terms of mining personal qualities (for lack of a better word) rather than an excess of labour – looms large in this approach to game production. (Whether game makers themselves see this as exploitation is another matter.)

Still, it’s worth redirecting any misgivings about these games towards a prominent alternative: namely, live service games that typically rely on exploitative profit mechanics such as ‘loot boxes’ for their ongoing sustainability. Compared with titles that employ the worst design philosophies the global games industry has adopted, it’s hard to argue that polished, narrative-focused indie games are ultimately an undesirable trend. If enough of these games are successful, ‘boutique indie’ may represent a step towards Australian studios’ further professionalisation – and if the demand for smaller, more polished titles continues as it has on platforms like Apple Arcade, Australian game makers will be well positioned to face the future.