The motorsports biography has become an increasingly prevalent subgenre in antipodean documentary over the past few years, to the point that we can identify commonalities in the form beyond the obvious subject matter. Roger Donaldson’s McLaren (2017) recounted the life of New Zealand Formula One champion Bruce McLaren, while actor-turned-director Jeremy Sims made his first venture into documentary filmmaking with Wayne (2018), an effusive hagiography of Australian motorcycle-racing legend Wayne Gardner. Now comes Brabham (2019), from yet another actor-turned-director, Akos Armont.

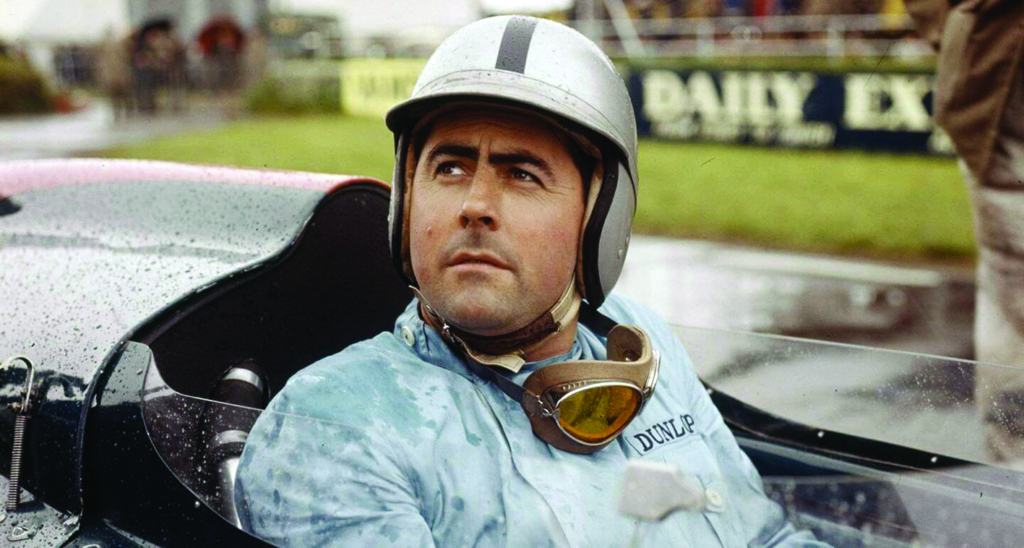

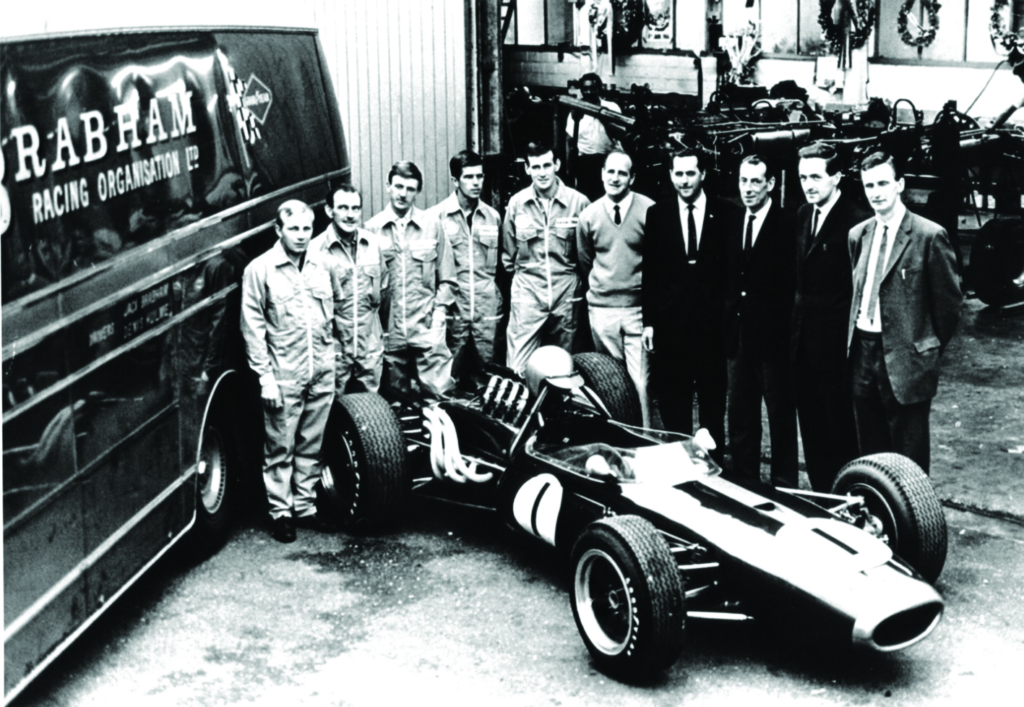

As the title suggests, Armont’s film retells the life story of Australian Formula One legend Sir John Arthur ‘Jack’ Brabham, whose most notable accomplishment (among many impressive deeds, it must be said) was becoming the first driver to win a Formula One world championship in a car he himself built – a feat he achieved at the French Grand Prix at Reims-Gueux in 1966.[1]See Cameron Leslie, ‘Sir Jack Brabham: ABC Grandstand Looks Back at His Three Formula One World Championships’, ABC News, 19 May 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-19/jack-brabham27s-greatest-triumphs/5462138>, accessed 21 February 2020. At a cursory glance, Brabham is typical of its subset: a fairly straightforward, chronological account of Jack’s career and personal experiences, told through talking-head interviews with his colleagues, contemporaries, family and friends; archival footage drawn from a variety of sources; and, occasionally, an animated interlude used to illustrate an anecdote (this technique is something it shares with Wayne).

The film comes at a time of renewed interest in the Brabham name and legacy. Under the aegis of Jack’s third son, David, the Brabham racing team and car-manufacturing concern unveiled a new car, the BT62, in 2018,[2]See Peter Anderson, ‘Brabham BT62 Unveiled’, The Redline, 3 May 2018, <https://theredline.com.au/brabham-bt62-unveiled/>, accessed 21 February 2020. and the story of how it came to be is the focus of Brabham’s closing act. Meanwhile a companion biography, Brabham: The Untold Story of Formula One, written by Tony Davis with contributions from Armont, was released in 2019.[3]Tony Davis, with Akos Armont, Brabham: The Untold Story of Formula One, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2019. The film demonstrates that Armont was given a remarkable amount of access to both Brabham-the-family and Brabham-the-company, with David gradually emerging as both a central figure in the narrative being shaped and unmistakably the driving force behind these interlinked projects. You could be forgiven for dismissing the film as part of a concerted effort to consolidate the ‘official’ legend, as it were – to construct an enduring, popular, digestible version of what was no doubt a complex and sometimes contradictory man and life (consider the rock band Queen’s wholesale whitewashing of their less-than-salubrious heyday in Bryan Singer’s 2018 Bohemian Rhapsody as the ur-example of this sort of thing). However, Brabham avoids the more obvious pitfalls of the ‘official biography’ subgenre by grappling with the very notion of legacy, and what it can mean to have to carry on in the shadow of an illustrious forebear. The title speaks volumes; after all, the film’s not called ‘Jack’, but rather ‘Brabham’. And, while the bulk of our admirably brisk eighty-four-minute screen time is spent on the senior Brabham’s exploits, Armont makes a good fist of trying to encompass all that that choice implies.

There’s a tragic irony in David, awed by but distant from his legendary father, dedicating himself to preserving and furthering the legacy of the Brabham name while seemingly not grasping the key that turned Jack’s engine.

Brabham begins with an ambiguous visual – Jack’s face, distorted as though viewed through water – and we hear David in voiceover hinting at his own uneasy relationship with his father’s image. Like his brothers, Geoff and Gary, David is a professional racing driver of considerable skill and achievement; in 2009, he became one of only four Australians to ever win the 24 Hours of Le Mans race.[4]See Joshua Dowling, ‘Brabhams Get Name Back on Track’, News.com.au, 28 January 2013, <https://www.news.com.au/tablet/brabhams-get-name-back-on-track/news-story/ee1ad26f66c8f709cd20d3f1db4f46ed>, accessed 21 February 2020. It’s an easy assumption to chalk at least part of David’s success up to heredity, if not dynasty, and the film does go to some lengths to show how the Brabham children grew up steeped in racing culture – which also meant spending their formative years among constant reminders of their father’s acclaim and prowess. David himself reminisces about growing up in a house full of trophies and championship cups and seeing them as ‘objects; I didn’t really understand what they were’. Later, he speaks about an angry confrontation with his father during which he is told he will never be a successful Formula One driver; the challenge spurs David on. And yet, in the opening moments of the film, we hear hints of a less cut-and-dried attitude to his father. While the exact meaning of what David is saying – at this point in the film, delivered free of context – is ambiguous, his unease with his position as the scion of a champion is not. ‘There are times I’d catch myself and go, “That’s not who I am. You’re so like your father?” There’d be something in the back saying, “Is this who you really are?”’

From this intriguing opening, we jump to the requisite information about Jack’s life, with Armont pulling footage from a Jack-focused 1976 episode of Mike Willesee’s This Is Your Life and Jack’s state funeral (the elder Brabham passed away peacefully in 2014 at the age of eighty-eight) to frame the story of his rise. The biographical details are interesting, but cleave to the expected characteristics of the ‘winner’ archetype: A precocious boy with a yen for speed, Jack raced go-karts as a youth before getting an apprenticeship in a machine shop at the age of fifteen, where he demonstrated natural engineering gifts that would serve him well for the rest of his life. Service in the Royal Australian Air Force during World War II interrupted his career, and, in the years after, he decamped to the United Kingdom, where car racing was on the upswing partly as reaction against postwar austerity and partly in a nationalistic drive to compete against the then-dominant Italian Maserati and Ferrari teams. Jack then connected with the British Cooper Car Company racing team and, from there, ascended an upward trajectory of success. He won his first Formula One world championship in 1959 by pushing his car – out of fuel – across the finish line.[5]See Leslie, op. cit. It’s an image the film will return to again and again: a near-perfect encapsulation of grit and determination.

Jack’s career is sketched out through archival footage and interviews, along with the odd artistic use of stock footage – Armont is not above inserting shots of snarling lions or marching soldiers to illustrate the masculine power and martial aspects of the car-racing game. These sections of the film are the most conventional, but not without interest. Motorsports historian Doug Nye offers vital context, while fellow driver Stirling Moss and Brabham engineer and car designer Ron Tauranac provide both technical details and colour. British artist and commentator Grayson Perry features to try to wrestle the Brabham story into some kind of cultural context – giving us descriptions of racing engaging with men’s ‘ancient primal instincts’, of the entire sport being ‘ritualised war’, of every race being ‘a dance of physics and mechanics’. It’s an effort to romanticise, if not outright mythologise, the world of car racing, and that’s an inherent part of the sport’s appeal; at one point, we hear the Monaco Grand Prix described as ‘the race of a thousand corners’, the poetry of the phrase counterpointing the hard-nosed, maths-and-physics-and-petrol-fumes reality of racing.

Indeed, Brabham frequently sets up seemingly irreconcilable contrasting perspectives on the events it depicts, and never more interestingly than when it asks us to consider the personal and familial cost of Jack’s career. A section irises in on the experiences of his wife, Betty, and how she was affected by being married to a man engaged in one of the most dangerous sports on Earth at the time. The film includes no interviews with Betty, who predeceased Jack by a year, but David – reflecting on the frequent fatal crashes that attended Formula One racing in the 1950s and 1960s – muses that ‘there was death every weekend. [My parents] went to a lot of funerals.’ He later ponders on his father’s frequent absences from home, as the latter often spent up to a year travelling on the racing circuit and worked eighteen-hour days even when with his family. ‘Did it affect us? It’s difficult to say.’

But not so difficult to illustrate – and, while David’s words might gently tiptoe around the price of his father’s success, Armont selects clips that speak volumes. Upon Jack’s retirement in 1970, Betty is presented with a ‘Ball and Chain’ award at a racing-industry function; whether this is good-natured ribbing or thinly veiled contempt is in the eye of the beholder. David observes of his childhood relationship with his father that the elder Brabham ‘didn’t have time to take much interest in what [the family] were doing’. Armont then cuts to David rehearsing his father’s eulogy. It’s a critical moment; the son is trying to lionise his father but still wrestling with his own obvious pain.

Even if David has difficulty stating it outright, the distance between father and family is palpable, but what remains mysterious is why Jack threw himself so wholeheartedly into his chosen sport. The mountaineer’s axiom ‘Because it’s there’ is as good a take as any. Jack apparently didn’t celebrate his victories, with one colleague describing him as being like ‘a Trappist monk’ in eschewing the hard-partying lifestyle of, by way of comparison, fellow Formula One driver James Hunt. Yet Jack’s ruthless pursuit of winning at all costs earned him the nickname ‘Black Jack’, and allegations of cheating are dismissed with ‘the only way you achieve maximum result is if you’re running at the very edge of the rules’. The wealth generated by Jack’s career is touched on via a couple of anecdotes about banking in Switzerland, yet it seems that he lived fairly frugally for a man of his position and resources. What actually drove him is lost to us.

And that’s what makes Brabham such an interesting film; there’s a tragic irony in David, awed by but distant from his legendary father, dedicating himself to preserving and furthering the legacy of the Brabham name while seemingly not grasping the key that turned Jack’s engine. The final section of the film deals with David’s successful legal battle to regain commercial control of the Brabham name[6]See Geoffrey Harris, ‘Motorsport: Brabhams Win Fight for Name’, Carsales.com.au, 10 January 2013, < https://www.carsales.com.au/editorial/details/motorsport-brabhams-win-fight-for-name-34427/>, accessed 21 February 2020. – the film suggests that Jack, oblivious to the long-term implications, had licensed it away – and to crowdfund Project Brabham, an effort to re-establish a Brabham racing team (he has since teamed up with Adelaide-based investment firm Fusion Capital).[7]See Stephen Ottley, ‘Family Business: The Story of Brabham Automotive’, Drive, 5 April 2019, <https://www.drive.com.au/news/family-business-the-story-of-brabham-automotive-121099>, accessed 21 February 2020. The resulting BT62 is showcased, and the future of the Brabham name, the Brabham team, the Brabham brand and the Brabham family seems assured. This sequence, more than any other, flies close to hagiography; it’s only a few degrees off being a corporate promotional video.

What saves the overall film is the leavening presence of David, who speaks of his fears that his own ambitions have, in turn, kept him distant from his children, and worries both that he is too much like his father and, in the way of the offspring of high-achieving parents, that he does not emulate him enough. ‘If you have a very successful or famous parent,’ he tells us, ‘their perfection is held up there not just by you, but by the public as well.’ In allowing this film to be made, David has threaded a very fine needle: paying tribute to his late father, honouring both the history and the future of his name, and allowing us at least some understanding of the heavy burden of dynasty.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Cameron Leslie, ‘Sir Jack Brabham: ABC Grandstand Looks Back at His Three Formula One World Championships’, ABC News, 19 May 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-19/jack-brabham27s-greatest-triumphs/5462138>, accessed 21 February 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Peter Anderson, ‘Brabham BT62 Unveiled’, The Redline, 3 May 2018, <https://theredline.com.au/brabham-bt62-unveiled/>, accessed 21 February 2020. |

| 3 | Tony Davis, with Akos Armont, Brabham: The Untold Story of Formula One, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2019. |

| 4 | See Joshua Dowling, ‘Brabhams Get Name Back on Track’, News.com.au, 28 January 2013, <https://www.news.com.au/tablet/brabhams-get-name-back-on-track/news-story/ee1ad26f66c8f709cd20d3f1db4f46ed>, accessed 21 February 2020. |

| 5 | See Leslie, op. cit. |

| 6 | See Geoffrey Harris, ‘Motorsport: Brabhams Win Fight for Name’, Carsales.com.au, 10 January 2013, < https://www.carsales.com.au/editorial/details/motorsport-brabhams-win-fight-for-name-34427/>, accessed 21 February 2020. |

| 7 | See Stephen Ottley, ‘Family Business: The Story of Brabham Automotive’, Drive, 5 April 2019, <https://www.drive.com.au/news/family-business-the-story-of-brabham-automotive-121099>, accessed 21 February 2020. |