A picture – or so the saying goes – is worth a thousand words. After all, to see something is to confirm its existence, verify its truth. But it’s not always as simple as that. When you’re looking from the outside in, it’s easy to miss the things that run beneath the surface. And a picture is never just that; the ‘truth’ of an image lies as much (if not more) in the framing of its photographer and the biases of its audience as it does in the captured lived experience of its subject.

The nature and ethics of responsible representation form a longstanding debate among those who build their careers around documenting others’ lives. As such, it is perhaps unsurprising that they also form the core themes of a documentarian’s first fiction feature. Co-written and directed by Ben Lawrence, Hearts and Bones (2019) is the story of two men united by their struggle to voice their respective traumas, set in motion by a photograph one took of the other during his moment of greatest suffering and vulnerability.

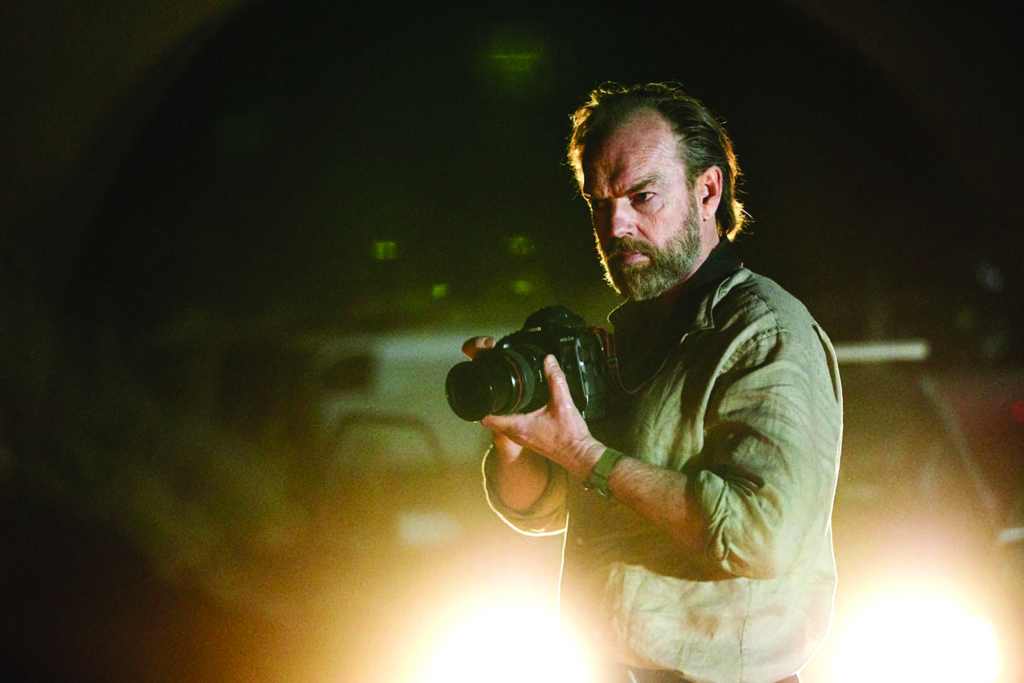

Sydney-based Dan Fisher (Hugo Weaving) is nothing short of a national treasure. A much-celebrated artist and fearless war photographer, he chronicles truths that many wouldn’t dare to go near. Recently returned from his latest trip, he has much to be grateful for: his loving long-term partner, Josie (Hayley McElhinney), who is newly expecting; his supportive brother, Graham (Alan Dukes), who readily provides him with the kind of grounding influence and logistical support artists often learn to rely on; a much-anticipated retrospective exhibition to celebrate his life’s work.

But the suffering Dan has borne witness to and the decades of distress he has endured in order to do so have left their mark on his body and mind. Additionally, the prior loss of his and Josie’s infant daughter, after a pregnancy that also threatened Josie’s life, means that, for Dan, the news of Josie’s second pregnancy is not the entirely happy occasion we might expect it to be. Of course, in the fashion of every stereotypically Aussie bloke, most of Dan’s suffering is locked deep inside him, and questions about his wellbeing are mostly met with platitudes or silence.

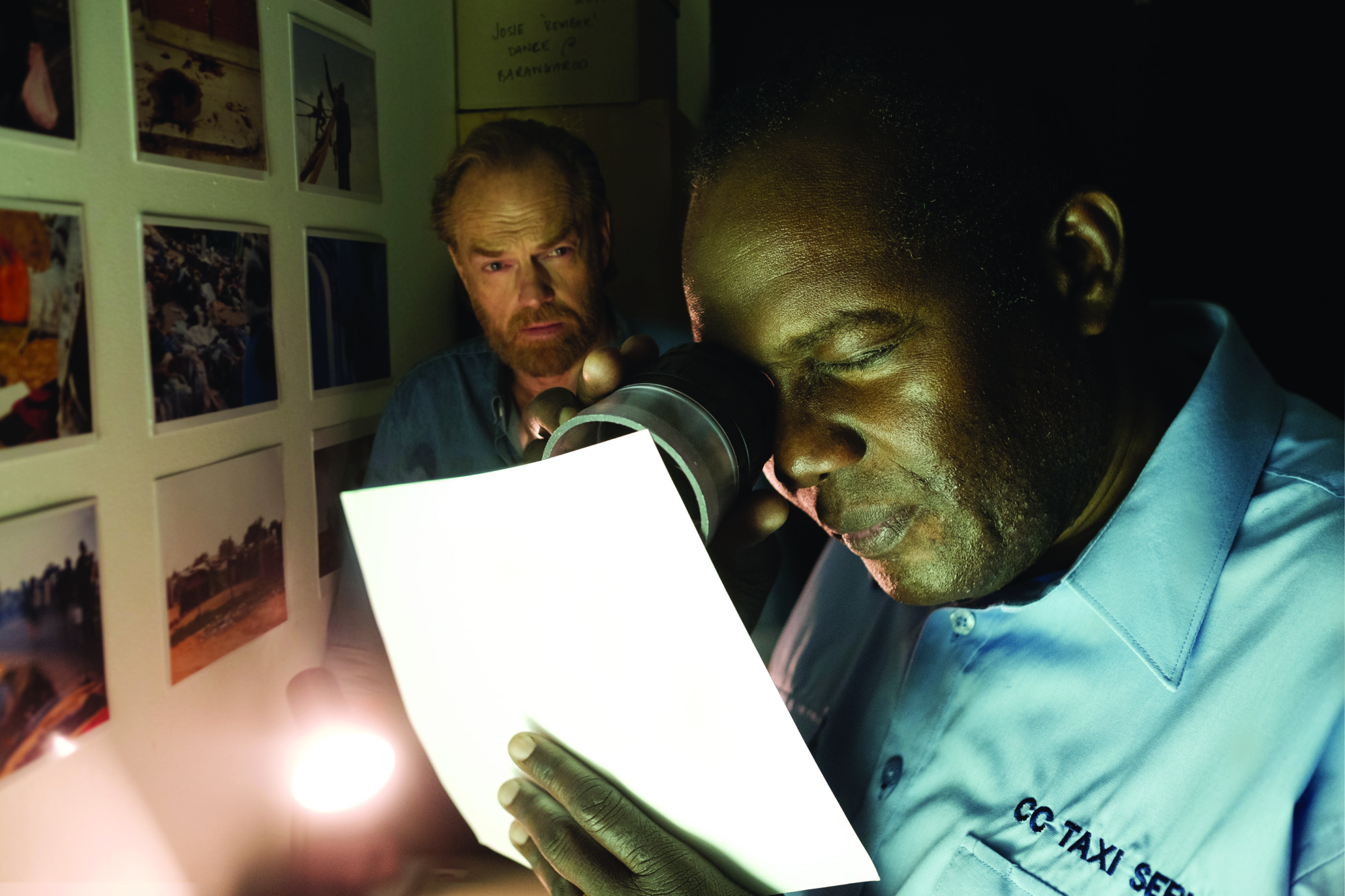

When cab driver Sebastian Ahmed (brilliantly portrayed by first-time actor Andrew Luri), who hails from South Sudan, seeks out and invites Dan to take snaps of his refugee community choir, at first, it’s as though he has entered Dan’s life to help the photographer find healing among others with similar experiences of extreme suffering and danger. But Dan and Sebastian have more in common than just the trauma of war: Sebastian, too, has kept his darkest days contained within him, hidden from his community and his wife, Anishka (Bolude Watson).

The conflicted ethics of war photography come into play when Sebastian asks Dan to withhold from the upcoming exhibition some photos of a massacre that happened in his South Sudanese village. As Sebastian reveals to Dan that he has been married before, and lost his wife and children to the very men Dan photographed, questions are raised as to who should have the right to decide which photos are displayed as well as whether Dan’s artistic ownership and the public’s right and desire to be informed about the true nature of a conflict outrank a victim’s wishes for privacy and dignity. These questions come to a head when Dan discovers that the hand holding a gun to another’s head in one of his images belongs to Sebastian – after his family’s slaughter, he had sought revenge on the perpetrators. When Josie shares this revelation with Anishka, the latter’s response perfectly encapsulates this ethical debate. She challenges Josie on her assumptions and judgements, which had been made based on limited information and a Western bias that sees Sebastian’s loss of his family and Josie’s own loss of her daughter as comparable:

No pictures of you during the worst moment of your life: losing everything, burying your dead. Hope – gone. Dignity – gone. There are no pictures of you in hell. When you lost everything, I bet people showed some respect. Looked the other way.

As in the ongoing debates in real life, there are no easy answers to the questions of ethics and ownership in Hearts and Bones. While Josie and Graham are adamant that Dan’s work should be his to do with as he pleases, Dan sympathises with his friend’s request and ultimately decides to hand over all photos of Sebastian’s village to him. Sebastian’s stance on whether or not the images should be displayed evolves over the course of the film, in parallel with his own process of stepping out from the shadow of his past and learning to share his history with those he loves.

The sensitive and multifaceted portrayal of the ongoing effects of trauma, particularly the unconstructive way in which many men seek to tackle them, is one of Hearts and Bones’ greatest achievements. In Dan’s world, the sound of a camera shutter, a malfunctioning washing machine, a slamming door evoke the echoes of gunfire. What is not expressed through words manifests itself in trembling hands and night terrors, and his usually calm and introspective demeanour gives way to crippling panic attacks. When it all threatens to become too much, rather than confront his demons, he starts packing his bags and planning his next trip to yet another war zone, perhaps to find a kind of comfort in an environment that more closely resembles the chaos he holds inside himself.

Questions are raised as to who should have the right to decide which photos are displayed as well as whether Dan’s artistic ownership and the public’s right and Desire to be informed about the true nature of a conflict outrank a victim’s Wishes for privacy and dignity.

Having several sources of support in place, along with the strength offered by his community, music and faith, Sebastian initially appears as a stabilising and grounding force who can balance out Dan’s erratic existence. But sudden outbursts of anger and a strong reluctance to share personal information with government sources hint at deep-seated feelings of insecurity. As Sebastian gradually confronts his role in the massacre in his village, and as Anishka slowly distances herself from him over the secrets he has kept from her, the film makes apparent his true instability, showing him lashing out violently against others and himself.

The mental-health journeys of the two male characters authentically mirror those of Australian men generally: In 2018 alone, 2320 men died by suicide. An estimated one in seven men experience depression, anxiety or both in any given year, yet men are far less likely than women to seek the support they need, and are three times more likely to lose their lives to suicide, even though women are statistically more likely to suffer from mental illness.[1]‘Statistics’, Beyond Blue website, <https://www.beyondblue.org.au/media/statistics>, accessed 15 October 2019. Behind these disheartening statistics lie toxic yet pervasive ideas surrounding Australian masculinity that leave little room for vulnerability, and favour stubborn stoicism and silent struggle over healthier and more productive coping mechanisms.[2]Shannon Molloy & Mike Cook, ‘Australian Men Are in Crisis, with Suicide Rates Rising. Meet Some of the Men Who’ll Die This Week’, News.com.au, 11 June 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/mind/australian-men-are-in-crisis-with-suicide-rates-rising-meet-some-of-the-men-wholl-die-this-week/news-story/4488a31ab0392ce1f7ee1a8717e73d38>, accessed 15 October 2019.

That Hearts and Bones excels in its realistic portrayal of hardship is no surprise, given Lawrence’s prior body of work. In 2016, he co-directed the three-part ABC series Man Up, which explores male suicide and mental health in Australia. In 2018, he released his first feature documentary, Ghosthunter – which won the Documentary Australia Foundation Award at that year’s Sydney Film Festival (SFF), and has since been adapted into a podcast[3]The Ghosthunter podcast is available via Audible, <https://www.audible.com.au/pd/Ghosthunter-Audiobook/B07V2NB3QC?source_code=AUDOR02807221900GM>, accessed 15 October 2019. For more on the documentary, see Hanna Schenkel, ‘Stirring Up Spectres: Ben Lawrence’s Ghosthunter and the Documentarian’s Duty of Care’, Metro, no. 199, 2019, pp. 92–7. – a project that involved working closely with his subject, Jason, over the course of seven years. Their investigation of Jason’s childhood allowed him to create a gripping and insightful account of the far-reaching consequences of child abuse and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. On top of his background as a filmmaker and photographer, Lawrence further drew on the accounts of real war photographers and also collaborated with members of Sydney’s South Sudanese community – including human-rights lawyer Deng Adut, who acted as a consultant on the film.[4]‘Realism the Key for New Film Hearts and Bones’, media release, Screen Australia, 20 June 2018, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/media-centre/news/2018/06-20-realism-the-key-for-film-hearts-and-bones>, accessed 15 October 2019.

Lawrence’s background in documentary shines through in his approach to everything from story development to filming. The script, which was first conceived in 2002 and co-written with Beatrix Christian, was, according to Lawrence, ‘really pieced together [from] real life experiences’;[5]Ben Lawrence, in Perri Nemiroff, ‘Hugo Weaving & the Hearts and Bones Team on the Audition That Drastically Changed the Movie’, Collider, 14 September 2019, <http://collider.com/hugo-weaving-interview-hearts-and-bones/>, accessed 15 October 2019. among these was Lawrence’s encounter with a Bosnian women’s choir while working on a project with Amnesty International, which saw each member of the choir introduce herself individually, a scene directly mirrored in the film.[6]Ben Lawrence, in Hearts & Bones post-screening Q&A, Sydney Film Festival, 16 June 2019. Lawrence also allowed his actors significant freedom to inform their characters and, in places, reworked the script to accommodate their needs and suggestions. For example, Anishka was initially conceived as Turkish, and her pregnancy was added to the script because Watson was actually expecting at the time of filming.[7]See Nemiroff, op. cit.

The mental-health journeys of the two male characters authentically mirror those of Australian men generally … Behind disheartening statistics lie toxic yet pervasive ideas surrounding Australian masculinity that leave little room for vulnerability, and favour stubborn stoicism and silent struggle.

Lawrence’s willingness and ability to draw on real life to inform his creative work enormously enriches his characters and more than makes up for a script that in some areas falls slightly short. While Dan and Sebastian are extraordinarily well-rounded and sympathetic protagonists, their families at times appear two-dimensional. The depiction of Josie feels especially shallow compared to the rest of the core cast, and her decision to reveal Sebastian’s secret to his wife seems simplistically vindictive. Sebastian, too, seems to make an uncharacteristic choice at a key point in the film: he brings up Dan’s exhibition and the contentious photographs right after Dan reveals a discovery that would have profound emotional and practical impacts on Sebastian’s life. These moments feel like they are mere components of a plot-driven script that needs to move its narrative to the next stage, hindering character arcs and story events from unfolding organically.

Luckily, these small flaws in the script are more than made up for by the production’s stellar acting, sensitive portrayals of difficult subject matter and a host of intelligent artistic choices. The brittle humanity of the characters is brought to life beautifully by Rafael May’s sensitive score, which is characterised by a pulsing undercurrent of shimmering high-strung acoustic-guitar motifs, and solo violin and cello movements that betray the weariness, pain and love on screen. May, who previously worked with Lawrence on Ghosthunter, acted as producer for the refugee choir as well. In this role, he worked with Luri, who also provided his own compositions, and choirmaster Jonathan Pease to create intimate and joyous music that would be authentic to the culture of a South Sudanese refugee.[8]Rafael May, email interview with author, 30 August 2019. As a result, music as a form of healing and community emerges as another core theme of the film, and audiences at the SFF world premiere were particularly enthralled with the men’s captivating performances on screen, if their post-screening queries were anything to go by. At the same time, Hearts and Bones is a rare modern feature that allows for ample silence, providing breathing room for Weaving’s and Luri’s layered performances to blossom to their emotional peaks.

Cinematographer Hugh Miller’s shots construct a landscape for Lawrence’s characters to move within that is at once strongly tied to Western Sydney, where the story is set, and also universal enough that it could be any major city around the world. The exquisite interplay of light and dark in many of the scenes brings to mind Miller’s previous work on Ghosthunter, as well as certain aspects of Lantana, the 2001 Australian classic directed by Lawrence’s father, Ray. Sequences are also set up intelligently to provide visual cues for the emotional states of each character – most effectively, several pivotal conversations are shot from either side of closed screen doors, the metal bars creating poignant metaphors for Dan’s and Sebastian’s decisions to lock themselves up emotionally and for the distance they are feeling from the rest of the world in those moments. Despite these choices betraying a deeply considered and artistic approach on Miller’s part, the film still presents itself in a realist style that both emphasises the everyday-ness of the story Lawrence is seeking to tell, and provides a visual link to his own documentary background.

As a documentarian, Lawrence seemingly can’t resist ultimately bringing his audience back to the real world, seeing out the end credits with the work of several real war photographers who have showcased the movement of refugees throughout various conflicts and periods. Set to Talking Heads’ ‘Road to Nowhere’, this closing sequence is a suitable nod to the dangerous and traumatising work of documenting conflicts. Further, Sebastian and Dan’s story helps to somewhat strip these images of the usually solely political lens Western audiences might view them through, introducing a more human element to our conception of the individuals depicted, and keeping the potentially misleading nature of a well-framed and -timed image front of mind.

Given Lawrence’s own background in filming deeply vulnerable subjects, as well as his obvious and well-documented concern for doing so without causing additional harm,[9]See Jason Di Rosso, ‘Ghosthunter – Interview with Filmmakers Ben Lawrence and Rebecca Bennett’, The Screen Show, ABC Radio National, 21 June 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/the-screen-show/the-hub-on-screen-template-segment/9885674>, accessed 29 October 2019. this juxtaposition of iconic photographs with a story of conflicted ethics could be interpreted as Lawrence’s response to the question of responsible representation. When viewed through this lens, Hearts and Bones serves as a reminder for Lawrence’s fellow photographers and filmmakers to keep the agency and interests of their subjects at the forefront of their work, and to approach such work as a means of amplifying disadvantaged voices rather than a tool for speaking on their behalf.

At the end of the day, while a good image is invaluable for helping people connect with and understand an event, pictures alone are not sufficient to get at the heart of a person’s life and experience. The desire and drive to not only share stories but also ensure they are told responsibly are fundamental to building connection as well as finding support and healing.

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘Statistics’, Beyond Blue website, <https://www.beyondblue.org.au/media/statistics>, accessed 15 October 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Shannon Molloy & Mike Cook, ‘Australian Men Are in Crisis, with Suicide Rates Rising. Meet Some of the Men Who’ll Die This Week’, News.com.au, 11 June 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/mind/australian-men-are-in-crisis-with-suicide-rates-rising-meet-some-of-the-men-wholl-die-this-week/news-story/4488a31ab0392ce1f7ee1a8717e73d38>, accessed 15 October 2019. |

| 3 | The Ghosthunter podcast is available via Audible, <https://www.audible.com.au/pd/Ghosthunter-Audiobook/B07V2NB3QC?source_code=AUDOR02807221900GM>, accessed 15 October 2019. For more on the documentary, see Hanna Schenkel, ‘Stirring Up Spectres: Ben Lawrence’s Ghosthunter and the Documentarian’s Duty of Care’, Metro, no. 199, 2019, pp. 92–7. |

| 4 | ‘Realism the Key for New Film Hearts and Bones’, media release, Screen Australia, 20 June 2018, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/media-centre/news/2018/06-20-realism-the-key-for-film-hearts-and-bones>, accessed 15 October 2019. |

| 5 | Ben Lawrence, in Perri Nemiroff, ‘Hugo Weaving & the Hearts and Bones Team on the Audition That Drastically Changed the Movie’, Collider, 14 September 2019, <http://collider.com/hugo-weaving-interview-hearts-and-bones/>, accessed 15 October 2019. |

| 6 | Ben Lawrence, in Hearts & Bones post-screening Q&A, Sydney Film Festival, 16 June 2019. |

| 7 | See Nemiroff, op. cit. |

| 8 | Rafael May, email interview with author, 30 August 2019. |

| 9 | See Jason Di Rosso, ‘Ghosthunter – Interview with Filmmakers Ben Lawrence and Rebecca Bennett’, The Screen Show, ABC Radio National, 21 June 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/the-screen-show/the-hub-on-screen-template-segment/9885674>, accessed 29 October 2019. |