As anyone who frequents film festivals of any scale can attest, there’s a near-ritualistic approach to scheduling as one maps out the sequence of movies one hopes to see. Running times, venue locations, care factors – all come together in an often much-laboured final timetable constructed to ensure the optimum festival experience. While it’s hard to think of an exercise more intrinsically bourgeois in the context of the contemporary art world, it is also, to be fair, a lot of fun.

These were the thoughts I was having as I sat patiently in a giant cinema in Toronto’s downtown Scotiabank Theatre, about two blocks away from the prestigious heart of the Toronto International Film Festival, the TIFF Bell Lightbox. This was the terrain across which we comrades-in-scheduling trudged back and forth, between films passionately anticipated and, well, those that just happened to fit neatly into gaps until the next films-passionately-anticipated. While, for me, the world premiere of Justin Kurzel’s fourth feature, True History of the Kelly Gang (2019), certainly fell into the former category, for the two young women sitting next to me, it was unambiguously the latter. As we chatted before the screening began, they were surprised to learn that Ned Kelly (played in the film by George MacKay) was even a real person – they were there because Nick Cave’s son, Earl, was in the film. Which he is, and his stand-out performance as youngest Kelly son Dan is, in fact, more than enough reason to catch this flick.

So I told them my story – or, more correctly, my story about the experience of growing up in a culture in which the shadow of Ned Kelly’s legend still looms large. I told them of lolly-fuelled school excursions and family daytrips as a child to Glenrowan to see a notoriously antiquated animatronic version of the iconic bushranger.[1]See the Glenrowan Tourist Centre website, <https://www.glenrowantouristcentre.com.au>, accessed 25 October 2019. I told them of the centrality of the Ned Kelly story not just to Australian film history, but to the history of cinema more broadly – Charles Tait’s 1906 film The Story of the Kelly Gang is recognised on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Memory of the World register as the first ever feature-length narrative movie.[2]See ‘The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)’, Memory of the World, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization website, <http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/memory-of-the-world/register/full-list-of-registered-heritage/registered-heritage-page-8/the-story-of-the-kelly-gang-1906/>, accessed 25 October 2019. I told them how, time and time and time again, filmmakers have returned to this outlaw tale, updating it for new generations with a regularity you could almost set your watch to. Most of all, I told them how Kelly has become the patron saint of a very specific kind of beatified hyper-masculinity tied to outlaw culture and the bad-arse ‘wild colonial boy’ legacy. At worst, I reminded them, this glorification provides fuel for a specifically Australian variant of that enduring piss-weak justification for toxic masculinity: boys will be boys.

Kelly has become the patron saint of a very specific kind of beatified hyper-masculinity … this glorification provides fuel for a specifically Australian variant of that enduring piss-weak justification for toxic masculinity: boys will be boys.

Much the same, I was informed, is true of Canada. It’s ‘a colonial thing’, they suggested, and, in the moments leading up to Kurzel’s film beginning, I received a crash course in Canadian outlaw history, hearing stories about similar figures whose names I’d never heard of, but whose misadventures – and legacies – struck me instantly as notably similar. As the lights went down, the two young women debated the surname of one of these figures; they, too, were taking their minds back to school-day history lessons, and their memories, like mine, were just as hazy around the edges.

It’s precisely within this haze that Kurzel situates True History of the Kelly Gang – both literally, within the dense fog and smoke running through his film as a consistent visual motif, and more conceptually, in its driving focus on the conscious act of history-writing itself. But, as an adaptation of Peter Carey’s 2000 novel of the same name (which won the Booker Prize the year after), this is no pompous exercise in theoretical finger-wagging; rather, it is intended as ‘a punk story for our times’.[3]Punk Spirit Holdings et al., True History of the Kelly Gang press kit, 2019, p. 2. The film even kicks off with a joke built into its opening title sequence: after the words ‘Nothing you are about to see is true’ appear on screen, all but ‘true’ fade away, with ‘History of the Kelly Gang’ subsequently manifesting – a masterclass in cinematic rabbit-out-of-a-hat-ness that establishes exactly what this film is saying about how we commemorate the past. Kurzel’s not here to muck around.

‘Boy’, ‘Man’, ‘Monitor’

That this cute little title gag is rooted in written language is no accident; True History of the Kelly Gang is nothing less than obsessed with acts of writing and reading, and its introductory trick hints at the broader thrust of the film: that ‘history’ is a construction, and history-writing itself is intrinsically dominated by biased power structures. In its adaptation journey, Carey’s thirteen-part novel has been skilfully reduced to a slender three-parter, working elegantly in the medium of traditional three-act cinema. The first two sections, ‘Boy’ and ‘Man’, are self-explanatory; the third, which focuses on the infamous showdown at Ann Jones’ Glenrowan Inn, is called ‘Monitor’, referring to the class of battleship whose design inspired Kelly’s helmet and armour[4]ibid., p. 5. – iconography that has since become synonymous with the man himself.

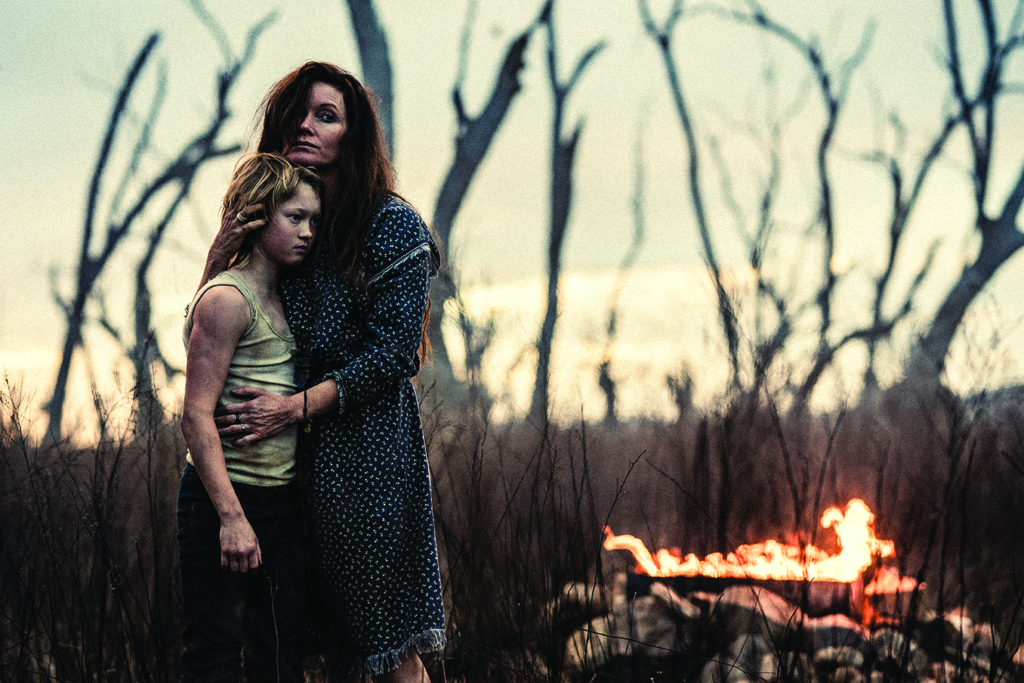

The film begins, we are told, in Australia in 1867. Ned’s father, Red (Ben Corbett), wears a fiery reddish-orange dress as he rides across the rural Victorian countryside, effectively (and permanently) excluded from the family home by its proudly Irish matriarch, Ellen (Essie Davis), Ned’s mother. Their house is sparse: an isolated corrugated-iron construction, little more than a glorified shed. But it is from here that Ellen makes her moonshine, runs her shebeen and, where needed to keep the business (and the family) afloat, offers sexual favours to the likes of local law-enforcement officer Sergeant O’Neil (Charlie Hunnam).

Despite a flicker of a better life being available to Ned (played as a child by the exceptional Orlando Schwerdt) early in the film – as a reward for saving a wealthy neighbour’s son, he is offered a free education at a boarding school in the township of Seymour – tensions between the Irish and English forbid Ellen from accepting such an offer (and, indeed, she is insulted to the level of being outright furious at such condescension). With her wild hair, foul mouth and functional frocks, Ellen is pragmatic and proud in equal measure; she sends her mullet-haired son off with one of her many lovers, bushranger Harry Power (Russell Crowe), for an informal apprenticeship. This incenses the young Ned, who realises that his mother has so strategically planned his entry into a life of crime.

The film’s middle segment, ‘Man’, reveals an adult Ned – non-diegetic punk music playing in the background – as the central attraction in a bare-knuckle boxing match organised to entertain the elite. Soon thereafter, we meet his best friend, Joe Byrne (Sean Keenan), their relationship shown to be so emotionally and physically close that it’s difficult not to interpret it as in some way deeply romantic. In time, life happens for Ned; he falls in love with a pregnant sex worker, Mary Hearn (Thomasin McKenzie), and, despite his protestations, is encouraged to assist Dan in stealing horses, which the latter has been trained to do by Ellen’s young Californian fiancé, George King (Marlon Williams).

True History of the Kelly Gang is nothing less than obsessed with acts of writing and reading, and its introductory trick hints at the broader thrust of the film: that ‘history’ is a construction, and history-writing itself is intrinsically dominated by biased power structures.

Like his father, Dan has a penchant for frock-wearing, and the gang are soon marked by their shared affinity for rather lovely gowns. On one hand, as Dan explains, ‘Nothing scares a man like “crazy”,’ rationalising that their choice of wardrobe will disorient their opponents and give them an advantage in battle. But there is much more to this; with flashbacks showing Red in his red-orange dress recurring at significant moments in the film, True History of the Kelly Gang finds itself punctuated by an unrelentingly queer drumbeat stressing that there is not just power but pride in difference. This element of ‘queering’ goes beyond the subversion of gender norms. That the Kelly men wear dresses – a plot device present in both film and novel – is a creative intervention by Carey, and not based on historical fact; instead, it serves to emphasise the family’s links to Irish rebellion at the time, in the form of the fictionalised Sons of Sieve group.[5]See Heather Smyth, ‘Mollies Down Under: Cross-dressing and Australian Masculinity in Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 18, no. 2, May 2009, pp. 185–214; and Magdalena Ball, ‘Interview with Peter Carey’, Compulsive Reader, 18 March 2003, <http://www.compulsivereader.com/2003/03/18/interview-with-peter-carey/>, accessed 26 October 2019.

One cop-killing later and it’s game on for the Kelly gang. The climactic Glenrowan shootout at the heart of the final act staggers enticingly towards a total collapse into stylistic abstraction. Artistically, Kurzel is in full flight as he stages the confrontation, utilising cinematographer Ari Wegner’s handheld camerawork and editor Nick Fenton’s intuitive understanding of action and rhythm to his advantage as he pushes a dramatic sense of immediacy to its fullest potential. We are, quite literally at times, right in the guts of it. But, despite the deliberate sense of immersion engendered by the chaotic cinematography and the emphasis on first-person shots, Kurzel keeps alive the message he started with: history is hard to pin down.

Writing Ned Kelly vs Ned Kelly writing

True History of the Kelly Gang hinges, both narratively and thematically, around acts of writing. It is, fundamentally, epistolary in nature; the film begins with the adult Ned uttering in voiceover, ‘My dear child’. The story we are about to hear – the supposedly ‘true’ story whose factuality has already been undermined by the title sequence – is configured as a letter that Ned writes to his young child. It is a clarification, a defence and, perhaps most of all, a confession. ‘Secrets shackle one more than any chain,’ he writes.

Rather than a narrative gimmick, this act of writing is intrinsic to what True History of the Kelly Gang seeks to convey – not just about Kelly himself as a national icon, but about ‘history’ more generally. The film is about who owns, and has the right to recount, dominant narratives; about voice; as well as about who belongs in these ‘sanctioned’ stories and, just as importantly, who doesn’t. On this last front, the film is aggressively clear. For one, its notably queered aspects are reminders of often-buried, alternative stories about the past. Additionally, the prominence it gives Ellen as a controlling, defining figure in her son’s life repositions her as a major character in the real-world Ned Kelly’s mythology, extricating her from the margins to which women are traditionally condemned by Australian (patriarchal) history. And it doesn’t stop there – a reference to the gang being ‘stolen men in a stolen land’ is not lacking in political insight, either, a subtle allusion to the (still-unresolved) issues of displacement that have plagued our country’s Aboriginal peoples.

True History of the Kelly Gang finds itself punctuated by an unrelentingly queer drumbeat stressing that there is not just power but pride in difference. This element of ‘queering’ goes beyond the subversion of gender norms … to emphasise the family’s links to Irish rebellion at the time.

While the film is framed through Ned’s act of composition, as both a child and an adult, he is also revealed to be constantly reading, constantly watching – a challenge to the widespread myth that he was illiterate.[6]Historian Ian Jones suggests that this misconception is due to ‘the fact that his right hand was crippled by bullet wounds at Glenrowan and his Condemned Cell letters to the Governor are signed with crosses’; see Jones, ‘Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 66, Spring 2000, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-66/t1-g-t3.html>, accessed 26 October 2019. He takes it all in, and, in his letter, gives what he sees an overarching shape. Even the practice of writing is itself something he learned through mimicry, noting earlier in the film that Harry was writing his own life story. Time and time again, True History of the Kelly Gang features Ned speaking in voiceover, or else re-enacts his accounts of both history and historiography; ‘Every man should be an author of his own history,’ he says at one point. As the gang plan to lure the police to Glenrowan with a final gambit focused on taking Melbourne itself, Ned asks in a rousing rhetorical speech, ‘Are we going to rewrite our own history? Are we going to write it in blood? Are we going to kill some coppers?’

Underscoring Kurzel’s broader interest in historiography and the role of folklore in national identity, the film is framed simultaneously as both an (un)true story and an explicitly fictionalised Ned’s own version of events. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that questions of authenticity are explicitly raised throughout the narrative. Disgusted when the young Ned attempts to resist violence, an angry Ellen tells him, ‘Be who you were meant to be’; later, the venal Constable Alex Fitzpatrick (Nicholas Hoult) mocks the adult Ned with ‘You’re not the man you pretend to be.’ In these scenes, the film is suggesting that even Ned Kelly struggles to live up to the expectations of what being ‘Ned Kelly’ means in the national consciousness. Tellingly, it goes so far as to deny the on-screen Ned the chance to deliver his real-world counterpart’s famous (ostensible) final words: ‘Such is life.’[7]Even in the realm of real life, it seems history is murky: whether Kelly actually uttered these words is a matter of contention. See Allison Jess, ‘Paper Says Ned Kelly’s Final Words Were Not Such Is Life’, ABC Goulburn Murray, 17 November 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2014/11/14/4128818.htm>, accessed 25 October 2019. Instead, the statement is transmitted secondhand, by way of a figure of authority who soothes Melbourne’s upper classes with news of the outlaw’s execution.

With these issues of authenticity, voice, historiography, Otherness and power laid out on the table before us, Kurzel’s grand, conceptual finale chooses not to present a twist in the well-worn narrative, but instead circles around a question of audience – of who is watching. From the very beginning, Ned addresses his letter to his child, but it is no small leap to suggest that this is as much for Mary’s baby as something far more symbolic: that he is speaking to those who, like me, have been raised in the shadow of his more toxic folkloric legacy. What Kurzel offers us – not the outlaws, not the wild colonial boys, but the rest of us – is a powerful precedent in the context of national history-telling. As Ned states eloquently in voiceover near the film’s conclusion, wrapping up his letter, ‘Write your own history, for you are my future now.’ A vibrant, essential exercise in punk historiography, True History of the Kelly Gang reminds us that, when it comes to dominant cultural narratives, sometimes the only way to move forward is to rip them up and start again.

Endnotes

| 1 | See the Glenrowan Tourist Centre website, <https://www.glenrowantouristcentre.com.au>, accessed 25 October 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See ‘The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)’, Memory of the World, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization website, <http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/memory-of-the-world/register/full-list-of-registered-heritage/registered-heritage-page-8/the-story-of-the-kelly-gang-1906/>, accessed 25 October 2019. |

| 3 | Punk Spirit Holdings et al., True History of the Kelly Gang press kit, 2019, p. 2. |

| 4 | ibid., p. 5. |

| 5 | See Heather Smyth, ‘Mollies Down Under: Cross-dressing and Australian Masculinity in Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 18, no. 2, May 2009, pp. 185–214; and Magdalena Ball, ‘Interview with Peter Carey’, Compulsive Reader, 18 March 2003, <http://www.compulsivereader.com/2003/03/18/interview-with-peter-carey/>, accessed 26 October 2019. |

| 6 | Historian Ian Jones suggests that this misconception is due to ‘the fact that his right hand was crippled by bullet wounds at Glenrowan and his Condemned Cell letters to the Governor are signed with crosses’; see Jones, ‘Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 66, Spring 2000, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-66/t1-g-t3.html>, accessed 26 October 2019. |

| 7 | Even in the realm of real life, it seems history is murky: whether Kelly actually uttered these words is a matter of contention. See Allison Jess, ‘Paper Says Ned Kelly’s Final Words Were Not Such Is Life’, ABC Goulburn Murray, 17 November 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2014/11/14/4128818.htm>, accessed 25 October 2019. |