By Jenny Sweeney

“I hate being called a beaver, don’t you Louise?”

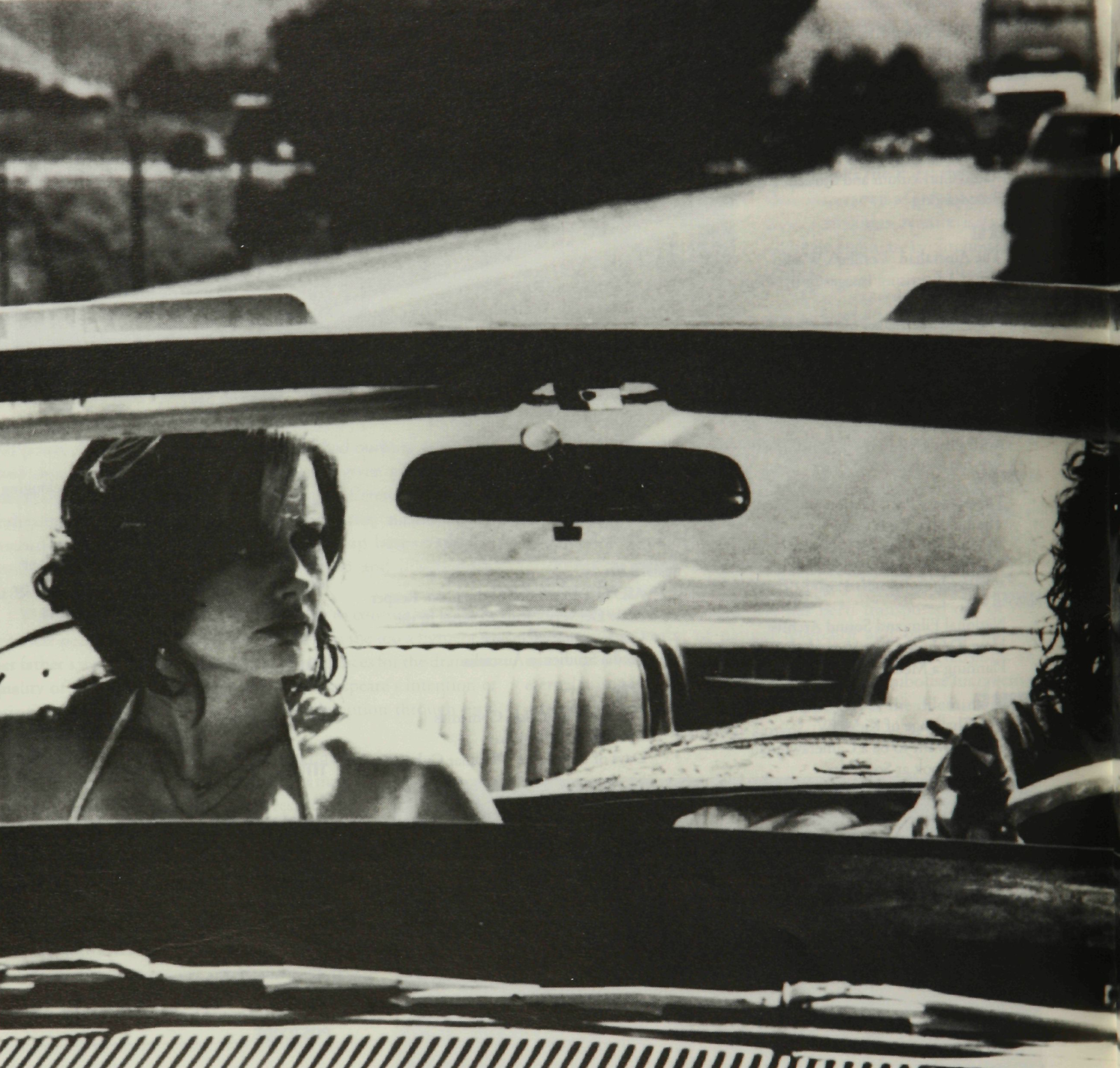

Thelma, and her best friend Louise, shoot at the sexist truckie’s truck. A glorious orange fireball erupts as the fuel ignites and the tanker explodes. It’s a jubilant moment; a sweet ka-boom. In my heart I was cheering – go Thelma! go Louise! … keep going! … blow up the trucks of all sexist truckies wherever they may be! And I pictured them standing, hands on hips, with stirring music playing and a voice-over saying something about justice and respect. In mid-flight, Thelma and Louise can do anything. They seem like the super sexism-patrol; warriors, heroes and rebels on a roll. But just as the height of noon contains the seeds of midnight, the freedom flight is the inverse of bondage.

Just a few days ago Thelma (Geena Davis) was a bored housewife, married to Darryl (Christopher McDonald) the barbarian. Louise (Susan Sarandon) was a waitress who was stuck in a rut waiting for her boyfriend to get serious at last and marry her. They both lived inside the comfort zone, safe and predictable and semi-conscious. Women in the shadow of men. Thelma cannot speak to Darryl. Louise is ordered off the phone by a belligerent boss. The opening scenes of Thelma & Louise are a parody of the muted voice of the feminine in patriarchal society. The journey which takes them away from their men powerfully expresses one kind of trajectory away from masculine values towards a new awareness of the feminine and the risks and hazards involved.

On the way to their weekend getaway they stop at a bar in Arkansas. After a few drinks, Thelma lets her hair down and starts dancing with a local called Harland. The friendly local turns nasty and tries to rape Thelma in the carpark. Louise comes to the rescue. But the would-be rapist wants to have the last word. The last word is the last straw and Louise kills Harland. Thelma and Louise are on the run.

Questions concerning the morality of the film have focused largely on the level of violence. Women murdering men in a situation of sexual power struggle is naturally hitting some raw nerves. Some feminists seem uneasy about its merit as ideological role-model material. It has been condemned as being an attempt at raising a feminist discourse, while supporting patriarchal values, such as violence. The film, it is claimed, tries to justify murder on feminist-political grounds. The danger has passed when Louise shoots Harland – his murder is therefore inexcusable.

In a postmodern climate which encourages diversity of perspective and multiplicity of truth, it is lamentable to find critics adopting a fixed stance on the question of morality in Thelma & Louise.

My doubt concerning the validity of these sorts of criticisms is twofold. Firstly, they suppose that in order for a discussion of inequality in gender relations to be effective it must be politically pure and morally righteous. Otherwise, it is implied, the film is actually supporting the ‘bad’ behaviour we witness. The moral high ground thus secured by these sorts of criticisms effectively nullifies all the joy and exuberance, all the agony and doubt, and all the tension and mess of this wonderful film, crushed under the label of ‘ideologically unsound’.

Denying that women can and do feel violent or aggressive or angry assumes that a neat line can be drawn between gender differences. Grounded feminist ideologies are surely not proposing the end of masculine values, but rather entrance into a dialogue towards balancing. The explosions and the successful escapes, even the initial murder, are a release for some of the anger accrued over millennia. It is a daydream of a spectacular revenge which satisfies the rage, but refuses to dictate an ‘approach’ or new ideology of equality. It may be messy (and in fact untidiness is part of its strength) but it is not sanctimonious. It doesn’t plead, ‘Why can’t we all get along?’

Thelma & Louise provides a safety valve for some powerful emotional pressure. When Thelma and Louise flex some muscle, my soul starts singing the Hallelujah chorus.

Further, it is, I would argue, a false assumption that the film seems to endorse violence as a means of achieving feminist ends. Or that it is suggested that you can blow up someone’s truck because they call you a beaver. While violence remains an integral constituent in mainstream cinema, it may well be a justifiable concern. Indeed Thelma & Louise is undoubtedly morally clumsy. However, the themes and metaphors in the film, it appears to me, do not celebrate not denigrate individual acts of violence but rather battle itself. Conflict and a profound sense of outrage generates aspiration. It provides the impetus for the flight of Thelma and Louise. And the flight is of greater significance in the context of the genre (the road movie) and the narrative than the fight.

Secondly, many critiques operate on the assumption that there exists a clear singular ideology, an exclusive means for an analysis of films in which women are central. In recent years women have been increasingly portrayed in films as pivotal characters of force and strength. The change in the perception of how a female character can behave and how much control she can have in a given narrative has allowed some women to play, and enjoy watching, roles previously denied them. Ripley is the hero in Aliens, Clarice Starling solves the mystery of Silence of the Lambs and Sarah Connor is the only human adult in Terminator 2 who can save the planet. For some critics, this freedom for female characters to be heroic inevitably carries the burden of responsibility for dealing with the problem of gender bias in accordance with the preferred ideology.

To suggest that Thelma & Louise attempts to raise feminist issues for discussion and fails because it employs the traditionally male genres and values (such as violence) sets up closure. It is impossible to step out of the patriarchal system, yet a ‘feminist’ film is expected to, though this would effectively mean science-fiction. At the same time, neither the buddy movie nor the road movie are exclusively masculine genres. Beaches, for instance, is an excellent example of female friendship. The friendship which exists and evolves between Thelma and Louise is indicative of the intimacy more typical of female friendships. As they journey further, the expression of their amity deepens.

The concern with feminist ideology threatens to eclipse other qualities of the film which stand out in the memory. Remarkable dramatic features can be overlooked, like Louise’s driving, the spectacularly fast and long reverse she performs at a gas station, or the moment she walks away from the car towards the desert in the silence of the night. They move past the oil fields towards the Grand Canyon. The vast horizons they enter echo the movement towards an extended field of vision, away from the supremacy of the technological, in favour of an awareness of the earth. In the emptiness of the desert, away from their men, the routine, civilisation, Thelma and Louise exhume a sense of self. There is no overt ecological message in the film, nevertheless the desert experience, the awesome quality of the expanse of land and sky, contribute to the sense of renewal they experience.

Reading the issues of power, liberation and rebellion presented in the film within the complex network of socio-cultural frameworks yield complex and discontinuous points of view. At the same time it would be equally revealing to view the film from a psychological/phenomenological perspective.

Men and women alike have felt an emotional rapport with Thelma and Louise. One male friend of mine was especially moved by Louise’s moment in the desert, driving to Marianne Faithfull’s ‘Ballad of Lucy Jordan’. Men and women share in the desire that Thelma and Louise should make it to Mexico. Human emotions and desires, the urge for flight and freedom, are deeper expressions of the common problems and experience of being alive. Viewed in a broader philosophical sense, the themes in Thelma & Louise are concerned with the human response to the existential problems of freedom and limitation. In this connection, it is with regard to notions of the self that I prefer to view the film and the subjective response to it.

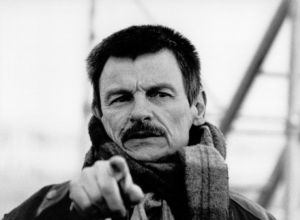

Director Ridley Scott says the film is an allegory of an encounter with one man. The eight male characters Thelma and Louise meet on their journey are like eight different aspects of one man. This way of thinking is in the realm of Jungian archetypes and philosophies of the nature of the self.

The characters in Thelma & Louise, in this sense, are at once representative of cultural archetypes (the Peter Pan, the rapist, the lover, etc.) and exemplify the human experience of multiple selves (Thelma is a housewife and a thief etc.). Existential philosophy expresses the need for accommodating paradox. Nietzsche declared that dualism is at the core of our nature. According to Kierkegaard, the human condition is a state of paradox, in movement between the two poles of limitation and possibility. Jung and the Jungians assure us we are composed of an entire ‘crew’.

The two friends are on a journey of self-discovery. Having lived at one pole of being, limitation, they have suddenly shifted to possibility. In the process they are adding more members to their crew. The journey, as it is reflected in our culture through myth and fairytales and religion, is both the means to discovering the multiplicity of the self and an archetypal motif in itself.

The road movie genre exudes a kind of promise expressing the power of the journey motif to fascinate. The sense of movement eases the yearning of the spirit to be free from the prison of the body. In motion, Thelma and Louise off-load the non-essential. Louise throws her lipstick from the car, she sells her jewellery and she loses her life savings. Louise ends her relationship to Jimmy. Thelma jettisons her marriage, and thus empowered, takes a lover.

Thelma and Louise have led passive lives but, travelling, find themselves in the province of the Rebel archetype. A form of possession takes place. Thelma is especially vulnerable to the thrill of her new persona. The progress of the Rebel invasion is like the flight path of an arrow. The arrow is ready to fire as Thelma begins her rebellion when she decides to go away with her friend without her husband’s permission. The murder in the carpark fires the arrow on an unalterable flightpath. The flight of the arrow continues on its own momentum, rising to its highest point (blowing up the sexist truckie’s truck, locking the obnoxious cop in the boot) before beginning its descent.

The two women move through a landscape which progressively opens up. The desert shots reveal more sky than earth. They seem to be flying. In mid-flight the thrill and sense of freedom is intoxicating. The car is like a plane, and Louise drives it like a pilot; reversing at full speed, under bridges, out of trouble again. The police pursue them in helicopters. Great swirls of dust caught in the down draught add colour to the giddy sensations as we are kept, as ever, in mid-air. It’s a party. Booze, good music, they practically dance and drive at the same time.

Nevertheless, the opposite pole of limitation is always present. The arrow flies momentarily. The earth opens to receive them. The Grand Canyon is the image of the mother calling back her children, the delineations of the earth. Before they end their journey, Thelma and Louise indeed do fly. In fact, our final vision of them is frozen in flight, laughing and defiant to the end. However, the power Louise and Thelma feel in the freedom and abandon of their flight is illusory. Limitation resides in the rules they have broken (not everything is permitted) and in the presence of the police. The Rebel and the Police are interdependent.

The Rebel figure is typified by J.D. (Brad Pitt), – James Dean? – a spunky young thief. His amoral, free-wheeling attitude is sharply contrasted by the good-guy cop (Harvey Keitel) trying to ‘help’ Thelma and Louise. The good-guy threatens to make hounding J.D. his life’s work. It is slightly implausible that a cop might feel responsible in such a paternalistic way for the plight of the two female friends. As a figure of the Good Father, he is conspicuously ineffectual.

J.D. awakens in Thelma the thrill of the Rebel and the Lover, which has her positively glowing. He doesn’t teach her how to be sexy, he simply allows her to be. He also demonstrates his robbery technique for Thelma and she rediscovers her sense of adventure. So when J.D. splits with Louise’s life savings, Thelma knows just what to do.

Darryl the barbarian watches the re-run of Thelma’s superbly polite but commanding robbery of a store on the police video. He can hardly believe his eyes. She was stuck in the daughter role within the marriage, while he was the Bad Father. After her adventures on the road, Thelma is hardly recognisable as the obedient daughter. She can never again fit back into the narrow existence of her old life. Her meeting with J.D. completes the invasion of the Rebel. Thelma revels in a sense of power which daughters don’t have.

The friendship Louise and Thelma share is more equitable. They shift power between them. Initially Louise takes control, but when the money is stolen she falls to pieces and Thelma steps in. They support and encourage each other; they stick together. They can be tearful without being branded weak. As they drive past the monoliths of Monument Valley, we can see vulnerability in their faces. They enter unknown territory with a view to experience it, not dominate it. Thelma says “I feel really awake”. And we can see how beautiful she is when she can be herself. “You’ve always been crazy, Thelma, you just never had the chance to express yourself until now,” says Louise.

Thelma & Louise is a film which deals with extreme ambiguity. The romance of the Rebel captures the imagination but its darker face is destructive. Suddenly the Hallelujah chorus stopped singing. Reacting against the lop-sided values of society and flirting with danger is an enticing stance. The powerful, raging force (and the glamour of a position of defiance) can become a dangerous hallucination.

Yet without the Rebel there is stasis and lifelessness. Although the Rebel effectively isolates, lost in excess and indulgence, when balanced with an awareness of the other, the energy can be used constructively. According to Camus, rebellion is the very foundation of human solidarity – sharing of strangeness and solitude from which human solidarity is born. The paradox is that strangeness unites.

Thelma & Louise had a strange and disturbing impact on me. I was stranded in the tension of conflicting urges. I felt triumphant in those moments of intoxicating power – the gun wielding show of defiance. And I was saddened during the lost, out-of-control moments pointing to inevitable destruction. Yet something in the mixture of elements, the vulnerability and strength, in Thelma & Louise is intensely satisfying. Louise and Thelma entered the dialogue; they died but they did not fail. I liked the mess and the chaos. I wanted to go through it all again immediately. And sometimes I wish I could recapture the feeling it gave me.

Against Thelma and Louise

By Adrian Martin

Speaking against a film which is a topical hit is an aggressive position from which to practise criticism. It makes me immediately uncomfortable, since I have no sympathy for the typical ‘strike’ manoeuvres of cultural debate – the kind of writing or talk which claims that anyone who likes or supports a particular contested film (for instance) is either ignorant, possessed of a coarse sensibility, or has been hopelessly sucked in by prevailing hype. It’s perfectly fine by me if someone likes Thelma & Louise, or is moved to make a case for it. For no cultural object is, in and of itself, good or bad, worthwhile or worthless; a part (perhaps a very large part) of its reality derives from the investments that people make in it. And already some very interesting ideas have been spun out of Ridley Scott’s film by investing fans (like Patricia Mellencamp in her 1991 Power Institute lecture).

Nonetheless, I find myself feeling very against Thelma & Louise. I want to use this occasion not to discredit anyone else’s intelligent, positive position on the film, but to explain (partly to myself) my own deep dissatisfaction and irritation with it – to work out the interpretative frames that might give rise to a negative investment in this particular cultural object.

Let me say straight away that my argument with the film has absolutely nothing to do – even unconsciously – with the idea that there’s something ‘unseemly’ about women protagonists running around an action movie shooting men (or trucks). There are plenty of female man-killers on screen I have no hesitation investing myself in, from Gena Rowlands in Gloria to Jamie Lee Curtis in Blue Steel. Indeed, I suspect even the imaginary male spectator hypothesised in some film theory would find very little to disturb their patriarchal psyches in Thelma & Louise. For as James Cameron proves every few years, there’s sometimes no greater fetishistic turn-on than a girl with a gun.

There’s another popularly expressed idea about Thelma & Louise – this one more of a journalistic cliche – that I don’t think gets us far into the film. It’s the notion that, for good or ill, the film’s essential strategy is to conjure female Rambos or Schwarzeneggers, simply by putting women actors into the tough hero roles that men would usually fill – a notion that led one reviewer to (rather oddly) describe the film as a ‘transvestite’. I don’t think this observation is even accurate. Films that really do have straight-out female terminators or robocops in this sense are obviously deemed so strange and unfit for mainstream theatrical consumption that they are emptied out, very quietly, into the home video stream (which is where the fetishists certainly find them). But Thelma & Louise is very far from this kind of mechanistically kinky exploitation cinema.

The current crop of important films about women who kill men – Thelma & Louise, Silence of the Lambs and Mortal Thoughts – are, more correctly, dialogical in nature. Film criticism has, in the last years, taken on the idea of dialogism from the work of Mikhail Bakhtin. It refers to the play of ‘voices’ or discourses in a text, often via the differential positions of characters – discourse not only in the sense of a train of speech, but the embodiment or tracing of a whole set of experiences or values. Of course, movies have always been in the business of making characters represent certain values, and then comparing or contrasting them so as to generate and resolve a fiction that is probably the essential semantic operation of the classical narrative film. But, as the classic ’70s critical text Women in Film Noir showed, the various discourses arrayed in much classical cinema are inexorably racked into a hierarchy, whereby some emerge as dominant (lawful, truth-telling, wise, etc) and others are subordinated (as ridiculous, duplicitous, marginal, etc).

A dialogical film, in its ideal state, would be something quite different: a textual ‘space’ wherein different voices, equally charged with personal and social significance, might pass, meet, echo, clash, enter into new and surprising relations. It would not be obsessed with laying down hierarchical tracks for its chosen elements, but would allow them to float, or ‘interleave’ (to use Marie Maclean’s term). In cinema history, two key dialogical filmmakers are Preston Sturges – whose films, as Jean-Pierre Gorin memorably put it, are like open courtrooms where people spring up to speak ‘in terms comprehensible only to themselves’ – and Jean Renoir. Thelma & Louise is, from the outset, a dialogical film because it so clearly sets about distinguishing, and then interrelating, the separate ‘voices’ of women’s and men’s experiences under patriarchy, without (it would seem) the clear-cut moral hierarchies of older Hollywood fictions. It can’t be a ‘transvestite’, since a great deal of its detail is lovingly given over to the ‘feminine culture’ of its main characters: for example, their ways of talking with each other about life, sex, and their mutual predicament.

Perhaps the richest period of dialogism in the American cinema is the 1970s. In the films of a mightily influential figure like Robert Altman, and in whole genres like the road movie, there arises a ‘post-classicism’, at least to the extent that everything loosens up: stories sprawl, minor or ‘eccentric’ characters suddenly hi-jack plots and take them into strange territories, unusual or never-before represented lifestyles proliferate, interleave, and make a hell of a noise. For Altman (as for his 80s protege, Alan Rudolph), the very act of making a film becomes less a matter of rigid control than of a highly intuitive setting into play of diverse, heterogeneous elements: actors who bring in their own characterisations and wander around the set interacting spontaneously with the other performers; script contributions employed in a freeform manner; a commissioned or plundered musical ‘voice’ floating on its own, independent path above the existing melange of images and sounds.

Thelma & Louise has been applauded as a film that ‘revisits the 70s’ in cinematic terms – not nostalgically, but in order to revitalise a mainstream cinema that has become in many cases safe, formulaic and predigested in the 80s. The idea is certainly exciting; whether Ridley Scott’s film lives up to it is quite another matter, and one worth testing.

One of the key ways that dialogism works in narrative cinema is through genre – specifically, the ‘mixing’ of genres whose elements are usually kept mutually exclusive. This is something we tend to forget about genres: they are not only formulae for generating stories, but also ways of adumbrating a ‘world view’ that includes some things whilst vigorously excluding others. That is why it is so startling when, for instance, certain male heroes are revealed to have parents (as happens in James Toback’s films), or Jamie Lee Curtis resolves her domestic tensions by arresting her father in Blue Steel. In these cases, it is as if the ‘world’ of the action film has suddenly been invaded by the concerns of ‘human’ drama – whether melodrama, family drama or ‘woman’s drama’.

Generically, 70s cinema tended towards a great fluidity. There is an easy continuum between the ‘art’ hits of Altman (M*A*S*H and Nashville) and his more seemingly ‘populist’ assignments (like his teen movie O. C. and Stiggs, scripted by National Lampoon writers); the same goes for Rudolph, moving between Roadie or Songwriter and Choose Me or Trouble in Mind. In fact, with the extraordinary interleaving of diverse genres in this period, it was quite impossible for even those in the distribution and exhibition business to separate ‘art’ specials from ‘entertainment’ fodder. Some directors strongly marked by the 70s have managed to continue making dazzlingly ‘mixed’ films that are surprising and confounding in this fashion, such as Jonathan Demme with Something Wild.

There is no more central example of the special situation of genre in the 70s than the road movie – the first ‘frame’ through which I want to try looking at Thelma & Louise. Throughout that decade and beyond, the road movie genre has moved back and forth between two extreme treatments, never really having to settle at either end. At one extreme, there’s the ‘arty’ road movies of Wenders, Pringle, Tanner, Storm, Kaurismaki and many others – films about emptiness, waste, disillusionment and open space. At the other extreme, there’s the ‘redneck’ road movie – films like Smokey and the Bandit or Clint Eastwood’s Every Which Way But Loose – in which ordinary outlaws exact marvellously vulgar revenge on every anally retentive authority figure in sight. These two types of road movie might seem very far from one another, but in fact, in practice, they are not – for even the most Antonioni-esque of road movies (like Two Lane Blacktop) simply has to digress into a bit of knockabout business or rev up with a rock song from a car radio to rendezvous with its redneck genre brother.

Thelma & Louise draws on a particular road movie formula – that of the couple on the run from the law, fleeing the scene of an initial crime, robbing banks en route for survival, reflecting on the homes and identities they leave increasingly behind. The ‘pleasure principle’ rules in this scenario until the ‘reality principle’ insists – with the inevitable arrival of police cars and helicopters ominously filling the sky and blocking the horizon of the road ahead. This very premise has an enormous amount of in-built, interleaving possibilities: for it has (potentially) dramatic pathos and tragedy as well as redneck hi-jinx, and films including Bonnie and Clyde, The Sugarland Express and The Legend of Billie Jean have succeeded brilliantly in milking the formula for both.

It’s the redneck comedy bits in Thelma & Louise – the exploding trucks, oafish husbands and spirited cussing about the two ‘bitches from hell’ – that seem to trouble some sensitive filmgoers, as if these moments were ‘out of place’ in a Ridley Scott film. But I don’t think it’s a problem that Thelma & Louise alternates ‘serious’ moments with comic ones in the sprawl of story-lines; in a road movie, that much is usually guaranteed. The problem for me is Ridley Scott’s particular sensibility at the helm of such a road movie.

Where any road movie should be loose, carefully destructured, open to all sorts of moment-to-moment possibilities, Scott directs with an empty, stodgy flair. His shots (characteristically) are showy, staged: they pin the characters into the frame like so many showcase butterflies, so that the camera and the lights can do a chintzy arabesque around them. Scott shows no feel at all for the high times on the road – for the reckless velocities and open framings that animate car films from Demme’s Citizens Band to Godard’s Passion. The film’s scenes of rednecks at play (in bars or cars) are like slick Southern Comfort ads – pumped up with painstakingly contrived bursts of ‘energy’. And they betray an uneasiness, a faint distaste on the part of the filmmaker: you can hear that Scott just can’t wait to drop gritty southern blues music for an extended play of Marianne Faithfull’s syntho-dirge “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan” on the soundtrack – accompanied, of course, by ghostly, flood-lit shots of the American landscape.

What I find inadequate in my own argument to this point is that (like so much negatively charged film criticism) it is normative; i.e., it posits (or assumes) what a certain mode of cinema ‘should’ (and shouldn’t) be, and then faults an individual film for not conforming, or living up to that model. So what if Thelma & Louise isn’t a road movie like other previous movies of the type? Sometimes the most interesting films that emerge in a tradition are those that hold nothing given or sacred, and that – whether by accident or by design – take the tradition somewhere else entirely. Even a ‘failed’ genre experiment – one which seems to have little feel for the genre in question – can do this, substituting for the old texture a different ambience, approach, sensibility. Some may argue for Thelma & Louise as a radical departure from the road movie norm in terms something like these – particularly since we have on our hands a predominantly ‘male buddy’ genre helmed by two women.

But before I take on that point, I need to get to the bottom of my dissatisfaction with the film by raising another interpretative frame. At root, Ridley Scott’s film strikes m e through and through as inauthentic. Now, authenticity is undoubtedly a dangerously vague aesthetic concept, one that is often wisely avoided by contemporary criticism. Authenticity isn’t something material you can isolate and point to in a frozen film frame; it’s a matter of how the film ‘feels’ – and how any two people feel about the one film is, as we know, rarely the same, or even comparable. Nonetheless, I think it’s worthwhile trying to nail down what it is in Scott’s style that might create a feeling of pervasive emptiness – the sense that he is a filmmaker on an endless quest for ‘cheap’ dramatic and comic effects.

Here it might be useful to draw a map connecting Scott to other filmmakers – so as to figure out the pertinent ‘family resemblances’. In articles in Filmviews and Metro, Gerald Fitzgerald has already proposed one such mapping for Scott, and it is a very suggestive one. For Fitzgerald, Scott can be aligned with Alan Parker, Adrian Lyne and Mike Figgis as one of the practitioners of a ‘new’ cinema – a cinema “saturated in significance, largely because of its deployment of a huge field of signifying processes always inherent in cinema” (Metro 84). He argues that style and content are so intricately interlocked, so intensely ‘worked over’ by these directors that their films achieve a radical extreme of ambiguity, textual mobility and polysemy – simultaneously a deconstructive “dissolution of forms” and a boundless generation of interpretative possibilities.

But I would suggest another reading of this map. Putting William Friedkin at the head of this family tree of Scott-Lyne-Parker-Figgis, and adding others including Oliver Stone, Ken Russell, Martin Campbell (Criminal Law), Morton & Jankel (D.O.A.) and Zalman King (Wild Orchid), one could hypothesise the existence of a certain cinematic tradition: the cinema of hysteria. This is a cinema indeed “saturated in significance”, but in a wild, scattershot way – calculated to press all buttons and have it all ways simultaneously. Robin Wood (in his book Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan) diagnosed in Friedkin’s Cruising, Scott’s Bladerunner and Richard Brooks’ Looking For Mr Goodbar an involuntary ‘breakdown’ of meaning, a symptomatic formation of ‘incoherent texts’ for our troubled times. What he perhaps did not see is that his examples were films actively seeking the production of incoherence – mainly for the sake of spectacular ‘effect’.

Effect rules in hysterical cinema: the sudden gasp, the revelatory dramatic frisson, the split-second turn-around of meaning or mood, the disorientating gear-change into high comedy or gross tragedy. It is hardly surprising that what links many filmmakers in this tradition is a background (and continued employment) in T V advertising and music video – those areas of audiovisual culture most governed by spectacular, moment-to-moment ‘sell’. Thelma & Louise is not the most hysterical of Scott’s films, but it certainly partakes of the familiar house-style.

It would be far too sweeping for me to now equate hysteria with inauthenticity. There are many fascinating films in the hysterical mode, some which have not only their own intensity, madness and inventiveness, but also their own ‘truth’ (Stone’s The Doors, for instance). But hysterical cinema is sometimes certainly empty and inauthentic cinema – entirely uninterested in its own material and the issues it raises, merely exploiting it for its artfully spectacular possibilities. Thelma & Louise strikes me as such a movie, with its twin heroines given to ominous, hushed, pointedly thematic statements like “we can’t go back now…”, its too-neat game with lit and unlit cigarettes marking the start and end of the voyage, and its ‘one good man’ (Harvey Keitel) clairvoyantly attune to the suffering of woman amidst a veritable sea of Southern male grotesques. (Is Keitel, one wonders with a shudder, meant to figure as the director’s stand-in? Such a self-flattering phantasm would certainly not be new in hysterical cinema.)

I’ve finally reached that interpretative frame that people are predominantly arguing about in relation to Thelma & Louise, is it really an instance of a feminist film made by a man from a woman’s (Callie Khouri’s) screenplay? It is not (as so few commentators have noted) the first or only example of a female-buddy road movie; Messidor, Heartaches, Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins have travelled this road before while, locally, High Tide offers an interesting interleaving of Paris, Texas with woman’s melodrama. But – even accepting the at least minimal dialogical genre-gender functioning of Thelma & Louise – what does it actually do to this film to have female heroes? In a very real and thorough sense, the film’s trajectory is pure late-1940s Hollywood. Like in the film noir or delirious gangster-action films like Joseph Lewis’ Gun Crazy, these protagonists ate doomed from the moment they cut free of society. Arguably, there is a sense conveyed by the film that Thelma and Louise are too wild, too free, too out of control, to the point where their only option is to surrender to what Freud once called the ‘death-drive’ – and Thelma & Louise, in its appallingly cheap, hysterical ending, is literally a film about a death-drive.

One might profitably argue here about the possible endings open to the film and its makers. Thelma and Louise could have been hauled back to the bosom of patriarchal society – something that might be viewed by the film and/or its viewers with either conservative approval or deep, subversive irony. They might have made it home free to Mexico, and kept up their high time – a not uncommon redneck movie ending (and one that might have worked). Of course, the ending that the film prepares us for (well in advance) is the classically fatalistic one – the meaningful frisson that the only escape from patriarchy is in a strangely euphoric slo-mo, freeze-frame, musical crescendo dive over a cliff.

A fatalistic ending to such a tale, however rueful or pessimistic, is of course not a ‘bad’ or invalid choice in and of itself. The conclusion of Thelma & Louise might have had a tragic wallop – a sense of loss and wasted possibilities, a felt insight into the brutality and limitedness of this Western, patriarchal world, like we find in the brilliant (and forgotten) 70s road movie by Spielberg, The Sugarland Express (to which Scott’s film can be closely compared). But it is hard for me to see the realised ending of Thelma & Louise as anything other than the ultimate in a very long line of cheap dramatic effects – a throwaway moment in the tradition not of the ending of Bonnie and Clyde but that of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

At least when Gun Crazy wallowed in its offering of fatalism, it was intuitively at the cutting edge of the contradictions of the immediate post-war era. Thelma & Louise seems to me a film in touch with nothing except the easy ‘topicality’ of its subject matter. It’s not, ultimately, a dialogical film because it grants so little reality or seriousness to any of its ‘voices’, female or male. There’s ambience, spectacle and ‘texture’ in Thelma & Louise as in every Ridley Scott film, but precious little else. It’s an example of a contemporary film so “saturated in significance” that it is virtually insignificant.

This article has been adapted from a review of Thelma & Louise broadcast on 3RN’s ‘Screen’ program.