On 20 November 1983, the US network television movie The Day After (Nicholas Meyer, 1983) aired for a record-setting audience of over 100 million. It created such a strong response in terms of nationwide water-cooler conversations and classroom discussions – as well as more formal, televised debates featuring leading academic experts and governmental figures – that it significantly bolstered anti-nuclear political activism in the United States.[1]See Marsha Gordon, ‘Is It Time for a 21st-century Version of The Day After?’, The Conversation, 24 January 2018, <https://theconversation.com/is-it-time-for-a-21st-century-version-of-the-day-after-90270>, accessed 29 October 2021. As a result of this wave of interest, the TV movie was given theatrical releases in several countries, including Japan, Russia and Australia.

The new documentary Television Event (Jeff Daniels, 2020), which had its Australian premiere at the 2021 Sydney Film Festival after various festival screenings in the US, traces the development and impact of Meyer’s film.According to Daniels, his interest in the project was initially personal; he tells me that he saw The Day After at age five with a large, extended family group, and – as a self-described ‘typical Reagan baby’ – remained obsessed with and afflicted by fears of nuclear disaster long after the nuclear disarmament movement had dwindled.[2]For more on the history of the nuclear disarmament movement, see Zoe Williams, ‘No More Nukes? Why Anti-nuclear Protests Need an Urgent Revival’, The Guardian, 7 September 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/06/no-more-nukes-anti-nuclear-protests-cnd-greenham-common>, accessed 29 October 2021. Since that fateful television airing, he’s been drawn to apocalyptic films of all kinds, including zombie films (‘Though they give me nightmares every time,’ Daniels laughs). Making this documentary constituted a kind of cinematic therapy: ‘I thought, “This is a good way to finally have less nightmares.” And it sort of worked.’

As Daniels researched the genesis and production of this unusually ambitious American Broadcasting Company (ABC) TV production, he became fascinated by the way The Day After represented ‘the Cold War through the eyes of a commercial TV network that has ulterior [profit] motives, and yet […] created something that had great impact’. His tight focus in the documentary tends to stay with the accounts of key players in getting the film made – Meyer, then–ABC Motion Picture Division president Brandon Stoddard, scriptwriter Edward Hume, producer Robert A Papazian and editor William Paul Dornisch.[3]Dornisch shares an editing credit on the film with Robert Florio. Their struggles included the network executives’ apprehensions about public reaction to the subject matter; difficulties getting sponsors (with popcorn mogul Orville Redenbacher finally taking a gamble and winning big); Meyer’s battles for creative control; censorship tussles; an attempt at government interference; and fights over the final cut of the film, which morphed from its original two-part, four-hour structure designed to run two nights in a row into a single two-hour film event.

Daniels’ deliberate strategy of constructing an oral history of a landmark production has led him to worry that this documentary will be misperceived as an extended ‘making-of’ extra, such as you might find on the DVD release of the movie. But Daniels argues he’s after bigger game, a film commemorating ‘a rare moment in our history when shared experiences were able to be utilised in some way to create a sense of urgency about important political issues’.

That said, it’s fascinating to watch The Day After now and consider how relatively mild the movie seems. We’ve been immersed in apocalyptic films for decades, to the point that when the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic led to statewide lockdowns in the United States, people cheerfully shared lists of pandemic-related films[4]See, for example, Jordan Crucchiola & Bilge Ebiri, ‘The 79 Best Pandemic Movies to Binge in Quarantine’, Vulture, updated 6 April 2020, <https://www.vulture.com/2020/04/best-pandemic-movies-on-netflix-hulu-prime-and-more.html>, accessed 29 October 2021. to watch while the virus ravaged the population, with titles including deadly-outbreak disaster movies The Andromeda Strain (Robert Wise, 1971), 1994 miniseries The Stand, Outbreak (Wolfgang Petersen, 1995) and Contagion (Steven Soderbergh, 2011), as well as particularly pertinent zombie films such as 28 Days Later (Danny Boyle, 2002) and World War Z (Marc Forster, 2013). We’re a long way from finding these kinds of films shocking anymore.

In any case, the aesthetic standard of the typical ABC TV movie was never high. With their muddy imagery, formulaic and luridly emotional narratives, uneven acting, and meat-cleaver editing designed around commercial breaks, even the most memorable of those films – such as The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (Randal Kleiser, 1976) and Trilogy of Terror (Dan Curtis, 1975) – only inspire the kind of wry affection reserved for camp classics. Daniels acknowledges the undeniable schlock level and ‘hokeyness’ of these movies, and in fact regrets that he couldn’t have dwelled a little longer on the unambitious network filmmaking context for such a thematically serious work as The Day After.

Meyer, hot off his hit movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), was aware of the step down then represented by working on a TV movie, and accepted the creative limitations he’d be dealing with. In interviews included in Television Event, Meyer describes his investment in his own political anti-nuke stance, and recognition that the lower standards and general unseriousness attributed to TV movies ‘allowed a back door into people’s consciousnesses’ because ‘nobody had ever seen anything close to this on network television’.

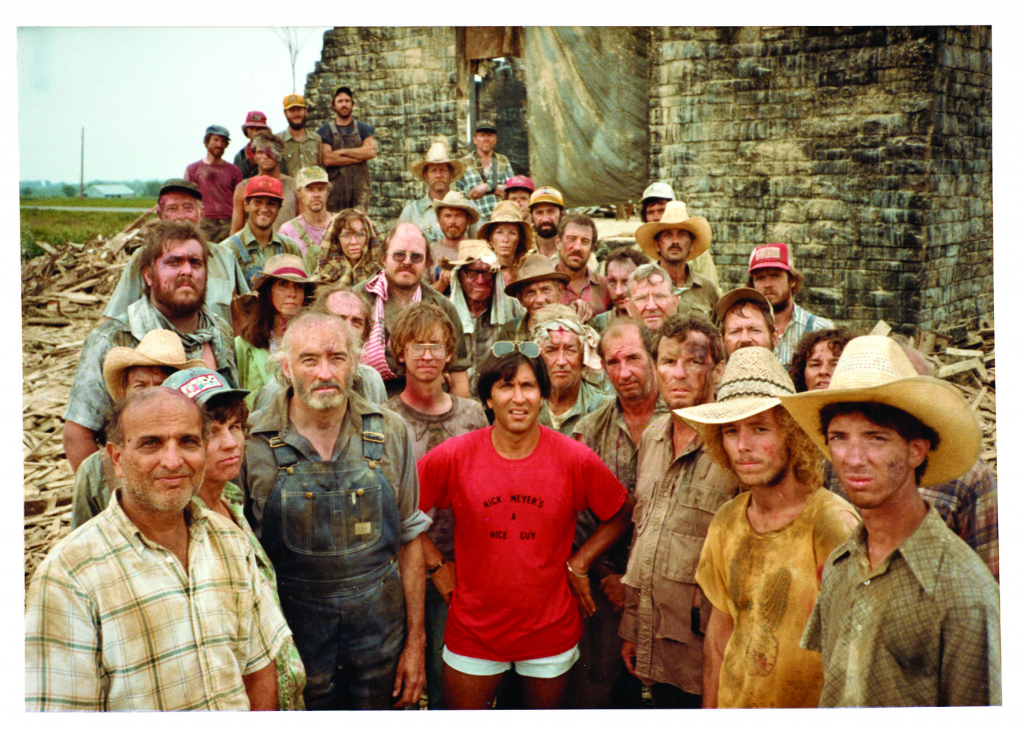

Given the restrictions of schedule and budget, and in spite of network badgering and interference, Meyer pulled out all the stops in elevating the material. He landed highly regarded actor Jason Robards for one of the lead roles, and enlisted the community of Lawrence, Kansas – chosen as the shooting location because of its centrality in the country as well as its nearby air-force base and many missile silos, which would make it a likely target in an all-out nuclear war – to fill many of the minor roles and turn out en masse to perform as extras. The film became a local passion project, Daniels notes, with ‘2000 volunteers from the University of Kansas’ going out ‘on a series of very hot days’ to play medical personnel and nuclear-fallout victims in an expansive field hospital sequence.

Meyer was aided by the in-depth research of producer Stephanie Austin – who went on to co-produce Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991) – in staging such central plot events as the nuclear missile attack sequence, which is still impressive today. It combines harrowing stock footage with simple shots made for the film – such as local abandoned barns exploding – and practical special effects that work surprisingly well. For example, the mushroom cloud images were inventively created by filming cream being poured into a glass of iced tea in close-up, and then turning the doctored image upside down.

Meyer largely stuck to Hume’s script, which relied on a long-established disaster film narrative formula, in which heroic figures rise to the challenge of confronting a terrifying and tragic scenario head-on. Disaster movies of this nature can be traced back to the early silent era, with housefire rescue films such as Fire! (James Williamson, 1901) and Life of an American Fireman (Edwin S Porter & George S Fleming, 1903). Depictions of ancient-times catastrophes such as Noah’s Ark (Michael Curtiz, 1928) and The Last Days of Pompeii (Ernest B Schoedsack & Merian C Cooper, 1935) were also good box office in cinema’s early decades, as were re-creations of more recent historical disasters like San Francisco (WS Van Dyke, 1936), about the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and In Old Chicago (Henry King, 1938), about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. And the 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic has appeared on screen on numerous occasions over the decades, ranging from three productions released in the year of the disaster through to Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster of the same name.

After the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, however, the Cold War and its nuclear arms race brought about an unprecedented surge of disaster films. These tended to feature the now highly recognisable narrative structure in which several unrelated characters feature in interwoven subplots; though they’re introduced to us leading ordinary lives, we’re already aware – thanks to the title, trailer and marketing – that they’ll be smashed by an impending cataclysmic event. The famous post–nuclear war disaster film On the Beach (Stanley Kramer, 1959), a clear antecedent of The Day After, was publicised with a similar saturation ad campaign emphasising the importance of its subject matter for each American citizen. But by the end of the 1970s – a decade that saw a spate of star-studded casts wandering unsuspectingly into their doom in big-budget films such as Airport (George Seaton, 1970), The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 1972), The Towering Inferno (John Guillermin, 1974), Earthquake (Mark Robson, 1974) and Avalanche (Corey Allen, 1978) – the disaster film had faded in popularity, with the genre not regaining momentum until the 1990s, when computer-generated special effects gave it new possibilities.[5]For more on the decline of disaster movie production in the US at the end of the 1970s, see Stephen Keane, Disaster Movies: The Cinema of Catastrophe, 2nd edn, Wallflower, London & New York, 2006 [2001], pp. 44–62.

The relative rarity of disaster movies at the time of The Day After’s broadcast may have been one factor in explaining the way the film struck a nerve with audiences, though the main factor was probably the savvy publicity campaign.

The relative rarity of disaster movies at the time of The Day After’s broadcast may have been one factor in explaining the way the film struck a nerve with audiences, though the main factor was probably the savvy publicity campaign targeting average Americans’ shaky state of denial regarding nuclear war. As Daniels attests,

I spoke with a lot of people who were adults at the time The Day After came out, and they say, ‘I didn’t really think about nuclear stuff, and I didn’t want to.’ I think that’s the point of why people at ABC wanted to make this, because they thought this is something people are either thinking about all the time or not thinking about at all, because they don’t want to, so if we can make something that really forces them to engage with this subject, then we could really have a real hit on our hands.

At the time of the film’s production, the Ronald Reagan administration was overseeing a huge military build-up and relying on a message that, as Daniels puts it, ‘America is strong and can survive anything that the Soviet Union can throw at us in terms of nuclear war.’ Getting wind of The Day After as a potentially agitating influence on the public, Reagan and his wife, Nancy, requested a private advance screening of the film at the White House; as Television Event recounts, the president found the film ‘a little too real’. The filmmakers had taken a particular chance in having a scene in which, following the nuclear attack, a Reaganesque president addresses the nation with hollow bravado; one character, listening to the address among a group of survivors, exclaims, ‘That’s it? That’s all he’s gonna say?’ Following this viewing, the administration submitted a list of recommended cuts and changes, to which Stoddard, in a rare moment of network TV courage, responded, ‘Tell them to fuck off; we’re not touching the film.’

While The Day After’s immense viewership and the extraordinary response to the film – in terms of both a public demand for clearer information about the possibilities and potential consequences of nuclear war and a powerful shared experience of alarm and dread – led to a revival of pro–nuclear disarmament demonstrations, Daniels concedes that the Reagan administration didn’t change its nuclear arms policy as an immediate result of the film’s impact. As former secretary of state Henry Kissinger expressed during a televised discussion on the issue inspired by The Day After, ‘Are we supposed to make policy by scaring ourselves to death?’[6]Henry Kissinger, in ‘The Day After Discussion Panel, ABC News Viewpoint November 20, 1983’, YouTube, 5 July 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzXcQ2Lr-40>, accessed 8 November 2021. In the documentary, Meyer says he shouted at the television image of Kissinger, ‘That’s exactly how I think you should make policy!’

However, the Reagan administration did change its rhetoric. In Reagan’s State of the Union address two months after The Day After ran, instead of emphasising American toughness and the survivability of nuclear war, he declared that ‘a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought’.[7]Ronald Reagan, quoted in Bernard Gwertzman, ‘Reagan Reassures Russians on War’, The New York Times, 26 January 1984, <https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/26/world/reagan-reassures-russians-on-war.html>, accessed 8 November 2021. And in the years that followed, it could be argued – and the documentary does argue – that the film contributed to ‘the biggest decline in nuclear weapons in history’ when Reagan and general secretary of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev signed an arms control agreement, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, in 1987.[8]See ‘What Is the INF Treaty?’, The Economist, 26 October 2018, <https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/10/26/what-is-the-inf-treaty>, accessed 8 November 2021. It should be noted, though, that a resurgent nuclear arms race rendered that treaty null and void in 2019; as journalist Taz Ali reports, ‘The nuclear arms race has accelerated in recent years, with the US, Russia, North Korea and China testing nuclear-capable hypersonic missiles which can potentially evade early warning systems and are harder to track.’[9]Taz Ali, ‘Fear of “Devastating” Nuclear War as World’s Major Powers Enter a New Arms Race’, i, 24 October 2021, <https://inews.co.uk/news/world/fear-of-devastating-nuclear-war-as-worlds-major-powers-enter-a-new-arms-race-1263713>, accessed 26 November 2021. The ultimate failure of the anti-nuclear campaign to rid the world of such devastating weaponry arguably affects the legacy of the film – or, at the very least, points up the need for another catalyst to revive the movement.

It’s hard to imagine, with the viewing habits of the contemporary public being so diffuse and niche-oriented, that this kind of shared experience of a media event could have such an impact today. Daniels acknowledges that the contemporary state of media reception makes such an event hard to replicate. But having begun production on Television Event while Donald Trump was running for and winning the American presidency – in the process, causing an acrimonious political rift in his own family that mirrored the widening divisions he saw in public discourse – he thought,

What a great time to remind people in the United States [that] there was a time [when] we still didn’t agree with each other, but we came together because of a shared experience that allowed us to talk about this vast global issue on an emotional level, and that changed. It wasn’t about right or wrong, because you can’t argue about emotions – you can try, good luck – but ‘I am scared’, you can’t argue with that. I was glad to see – and I tried to show in my film – that there was a lot of […] common ground, that people on either side of the issue should be [able to discuss it].

When interviewed in Television Event,the key players involved in making The Day After seem in fervent agreement about the importance of what they achieved. Meyer states, for example, that The Day After remains ‘certainly the most valuable thing I’ve gotten to do with my life to date’. And Daniels evinces no interest in challenging that point of view in his documentary, choosing instead to hold the film up as a reminder of the potential of media to help us ‘try to interpret and imagine the unimaginable of what we’re going through now’.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Marsha Gordon, ‘Is It Time for a 21st-century Version of The Day After?’, The Conversation, 24 January 2018, <https://theconversation.com/is-it-time-for-a-21st-century-version-of-the-day-after-90270>, accessed 29 October 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on the history of the nuclear disarmament movement, see Zoe Williams, ‘No More Nukes? Why Anti-nuclear Protests Need an Urgent Revival’, The Guardian, 7 September 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/06/no-more-nukes-anti-nuclear-protests-cnd-greenham-common>, accessed 29 October 2021. |

| 3 | Dornisch shares an editing credit on the film with Robert Florio. |

| 4 | See, for example, Jordan Crucchiola & Bilge Ebiri, ‘The 79 Best Pandemic Movies to Binge in Quarantine’, Vulture, updated 6 April 2020, <https://www.vulture.com/2020/04/best-pandemic-movies-on-netflix-hulu-prime-and-more.html>, accessed 29 October 2021. |

| 5 | For more on the decline of disaster movie production in the US at the end of the 1970s, see Stephen Keane, Disaster Movies: The Cinema of Catastrophe, 2nd edn, Wallflower, London & New York, 2006 [2001], pp. 44–62. |

| 6 | Henry Kissinger, in ‘The Day After Discussion Panel, ABC News Viewpoint November 20, 1983’, YouTube, 5 July 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzXcQ2Lr-40>, accessed 8 November 2021. |

| 7 | Ronald Reagan, quoted in Bernard Gwertzman, ‘Reagan Reassures Russians on War’, The New York Times, 26 January 1984, <https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/26/world/reagan-reassures-russians-on-war.html>, accessed 8 November 2021. |

| 8 | See ‘What Is the INF Treaty?’, The Economist, 26 October 2018, <https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/10/26/what-is-the-inf-treaty>, accessed 8 November 2021. |

| 9 | Taz Ali, ‘Fear of “Devastating” Nuclear War as World’s Major Powers Enter a New Arms Race’, i, 24 October 2021, <https://inews.co.uk/news/world/fear-of-devastating-nuclear-war-as-worlds-major-powers-enter-a-new-arms-race-1263713>, accessed 26 November 2021. |