You don’t understand a person in their lifetime; you understand them in their death. That, to me, is a more important thing – that you are forgiven and understood.

—Michael Leunig, The Leunig Fragments

When filmmaker Kasimir Burgess first approached cartoonist Michael Leunig to propose a film on his life made over the course of twelve months, little did he know that the process would extend to a commitment lasting more than five years – or that, during that period, he would lose all communication with his particularly reticent subject, via factors that ranged from Leunig suffering a near-fatal seizure to, at times, his simply refusing to engage.[1]Kasimir Burgess, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Madman Films, The Leunig Fragments press kit, p. 3.

Despite his initial reluctance to participate in the project, the cartoonist would go on to allow access to certain spaces and encourage the camera to focus on what he wanted to reveal, while simultaneously pulling away from Burgess and the production team at critical junctures. Long vaunted for his philosopher king’s ‘outsider’ viewpoint, and for what has been termed his ‘weaponised whimsy’,[2]See ‘Leunig’s Weaponised Whimsy’, Late Night Live, Radio National, 13 February 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/latenightlive/leunigs-weaponised-whimsy/11955568>, accessed 21 May 2020. the cartoonist ultimately presents as a disingenuous and unreliable narrator. The central question the film poses, then, is just how close viewers ought to be allowed to get to a subject: that is, when does an audience’s right to know supersede the right to privacy of the individual who is being investigated?

In the case of The Leunig Fragments, the answer should be simple. While the cartoonist is fiercely guarded, he also – as Burgess suggests through a layered collage of interviews and appearances – has a compulsion to be publicly recognised. Despite his protestations that he doesn’t ‘represent the power establishment, or the wealthy, the well-armed or the beautiful people’, Leunig seems to posit himself as a voice of national conscience; a theme that he returns to is that he is ‘an outsider’. Broadcaster Phillip Adams, however, notes in the documentary that ‘one could argue that [he has] become a total insider’, and that ‘there are dangers to becoming immensely popular’.

Politics and reaction

Perhaps the greatest danger that Leunig faces in the current climate of instantaneous reaction to any politician’s, journalist’s or cultural commentator’s work is the democratisation of opinion that social media has engendered. For many people, the news cycle has become a simulacrum:[3]For more on this concept, see Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Paul Foss, Paul Batton & Philip Beitchman, Semiotext(e), New York, 1983. in a time when many people use Facebook as their news feed, the temptation to scroll through, half-read articles and then react is stronger than ever. Consider, too, that news in this format is interspersed with posts from friends, social media–targeted advertising and Google analytics trying to work out your set of interests, and the current media landscape has never more acutely reflected Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that ‘the medium is the message’.[4]See Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964, pp. 7–23.

The immediacy of the outrage machine that this ecosystem fosters – and Leunig’s particular deftness at generating it – is evident in the Twitter storm and accompanying opinion piece, usually in a rival publication, that emerge every time he produces a cartoon that seems to take a particularly aggressive or reactionary stance.[5]See, for example, Eleanor Robertson, ‘Leunig’s Anti-vaccination Stance Reveals the Fantasy World He Lives In’, The Guardian, 19 August 2015, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/aug/19/i-dont-want-to-go-on-leunigs-anti-vaccination-mental-vacation>, accessed 21 May 2020. Once a darling of the left, Leunig has been known of late to take aim at parts of society that have traditionally been marginalised, such as the LGBTQIA+ community, while he has also drawn cartoons that lend support to the anti-vaccination movement.[6]See Ben McLeay, ‘Someone Needs to Check on Leunig Because His Shit Is Getting Real Weird’, Pedestrian, 6 December 2017, <https://www.pedestrian.tv/news/what-gives-leunig/>, accessed 21 May 2020. Nonetheless, his work remains politically eclectic; he has also used his platform to condemn the immorality of Australia’s asylum-seeker policy, and has expressed genuine interest in Indigenous issues – as seen in the documentary when archival footage shows him, along with famed Indigenous artist Michael Nelson Tjakamarra, walking the sacred caves of the Walpiri people in the Northern Territory and expressing heartfelt anger and sadness at the plight of the Stolen Generations.

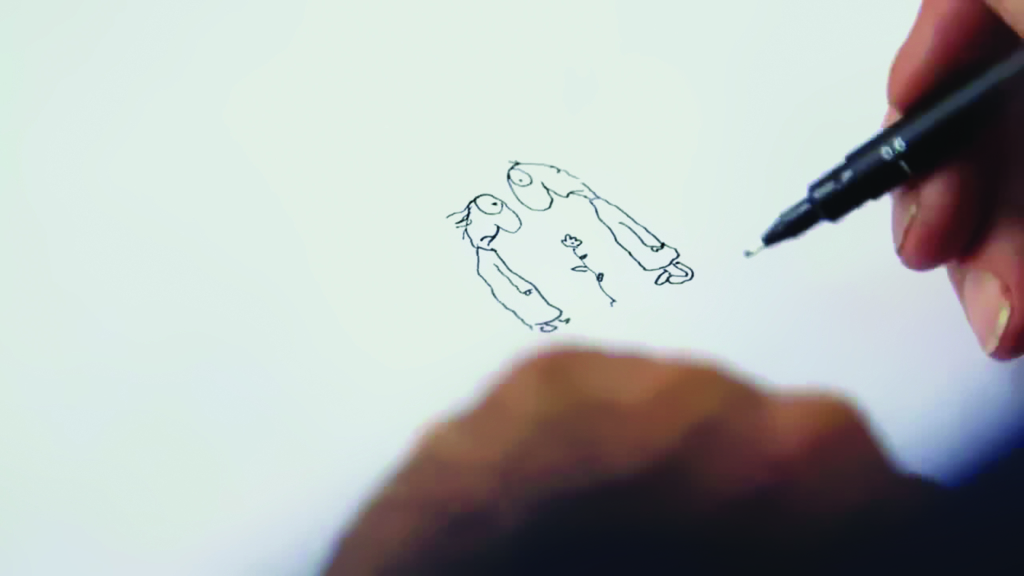

A dominant theme of his work, though, has less to do with politics than a feeling of being overwhelmed by the world and its many conflicts. In one anecdote in the film, the cartoonist recounts that he first drew his famous duck motif (a man riding a duck with a teacup on his head) as a response to his distress at the Vietnam War: an absurd response to an unbearable situation. When the cartoon caused consternation, Leunig says, he felt confused that critics didn’t seem to understand that there was no deep allegory intended – that the duck was just a duck. He goes on to describe ducks as a soul animal, and a force for good: if ever confused, he says, one should follow a duck.

An essential part of the construction of the film is bringing Leunig’s cartoons to life via animation and sound effects. Cartoons are carefully placed to make subtle statements about Leunig’s character; in one sequence, Burgess juxtaposes images of young troops being sent to the conflict and the famous photograph of the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém with an animated cartoon of Leunig’s showing a disapproving public reacting to the duck. Later, another animated sequence depicts the public decrying Leunig’s iconic character Mr Curly. These juxtapositions portray the tide turning against the once deeply beloved cartoonist.

Mysteries and obfuscation

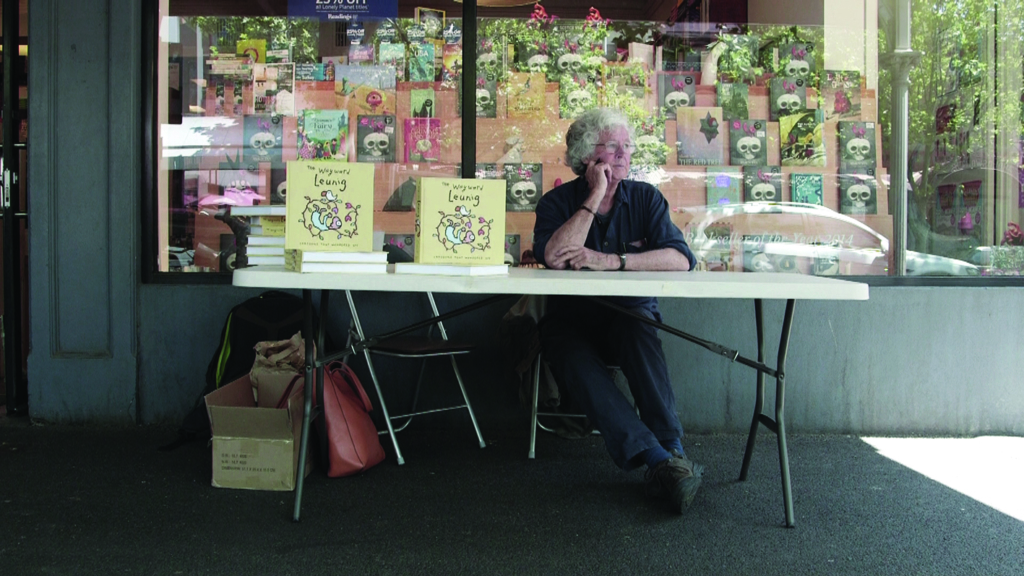

As both a reluctant documentary subject and – as satirist and poet Tug Dumbly (aka Geoff Forrester) points out in the film – a multimillion-dollar industry, Leunig embodies a contradiction. He remains one of the most recognisable faces in Australian culture, as multiple appearances on talk shows and breakfast television attest, even though he describes having received death threats in response to his cartoons. Like a moth to a flame, Leunig does want to be seen – however, it needs to be almost exclusively on his own terms.

When Burgess first meets Leunig to negotiate the terms on which the documentary will go ahead, cinematographer Marden Dean draws the audience in through conventions akin to tabloid television journalism. Peeking through the window of Fitzroy’s Tin Pot cafe at two men conversing about the private in public, the camera becomes the mystified viewer. We hear only fragments of conversations, and are given only fragments of information. This is the unspoken theme of the documentary: Leunig demands respect, privacy and the ability to create his own hagiography, all the while ensuring that the information he provides is vague and insubstantial, or profoundly contradictory.

Remaining an enigma is part of the Leunig brand, and, for an audience trying to fathom the man behind that brand, The Leunig Fragments can be a frustrating journey.

Although Leunig has worked for Fairfax papers for most of his prolific career, in the company of some of the most important investigative journalists in Australia, he claims in the documentary that he doesn’t know where his parents are buried; elsewhere, while going through photographs of his family, he casually mentions that his father was probably partially Indigenous. These mysteries that he lets slide out in casual conversation could, one presumes, easily be resolved and substantiated if that’s what Leunig wanted; but remaining an enigma is part of the Leunig brand, and, for an audience trying to fathom the man behind that brand, The Leunig Fragments can be a frustrating journey.

A restaged life

In The Leunig Fragments, we see live interviews that the artist has given in the past, along with on-stage appearances with musician Katie Noonan (with whom he co-wrote an album in 2018[7]See Steve Moffatt, ‘Leunig Quirk Gets a Double Outing’, The Daily Telegraph, 25 September 2018, <https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/leunig-quirk-gets-a-double-outing/news-story/2a36ff83485250cb74105a3fa9d4e43b>, accessed 21 May 2020.) and observations about him from other prominent Australians, including politician Bob Brown, fellow cartoonist Cathy Wilcox, newspaper editors, fans and friends. But, predominantly, the film is made up of recreations of Leunig’s childhood. Growing up in postwar Australia in a hardscrabble suburb like Footscray, with busy parents trying to juggle multiple children, can’t have been very easy for his generational cohort; and these reminiscences – as rendered by Burgess and Dean – are the most powerful and cinematically crafted aspects of the film. However, as much as they’re designed to give the audience a sense of how Leunig came to be the person that he is, they’re also a dramatic fiction guided by subjectivity.

Indulgent, beautifully shot and acted ‘sense memories’ dominate the storytelling. Child actor Liam Smith wordlessly represents a young Leunig in a series of vignettes that follow the narration of his early life: lying on the ground, looking at the light shine through a glass; listening to the sound of soil being turned in the backyard by his father; watching his mother care for his siblings; and falling in love with his first wife, Pamela, in primary school, among other idiosyncratic scenarios.

As the back and forth between Leunig’s past and present is explored, a central relationship is revealed – that with Joan Brogden, his primary school teacher. Brogden, played in flashbacks by actor Eloise Mignon, first recognised Leunig’s skill as a cartoonist and introduced him to a set of sophisticated international influences that ranged from the music of Joan Baez to the comedic stylings of Spike Milligan and The Goon Show, and Leunig recalls her as a spiritual parent. She is also a parent whom, during the filming of the documentary, he is losing. The camera follows him to Brogden’s hospital room as he holds the hand of the dying woman, who has had a series of intense strokes. Leunig tries to hold her gaze and, at times, expresses a feeling that they are present in a moment together; then that moment is lost.

Loss and grief permeate the film in a profound manner. During the filming of the documentary, Leunig lost another close friend, actor and satirist John Clarke, and it is clear that the cartoonist is contemplating his own mortality and the legacy he will leave. The picture that emerges is that he fears a lonely death, much as he lives a lonely life – a fact that is reinforced when Burgess interviews Leunig’s son Sunny, who ‘wouldn’t go and knock on his door’ even though he ‘just lives down the end of the street’ from his father.

It’s notable that Sunny is the only family member who agreed to appear in the film. Burgess could have examined the family relationships of his subject further – especially given that, as the documentary reveals, Leunig separated from his second wife, Helga, during the filming period – but evidently chose not to; as he puts it, ‘There are mysteries in family dynamics, and sometimes you can’t remember how something began, and I think that’s okay. The film’s not about that.’[8]Kasimir Burgess, quoted in Andrew F Peirce, ‘Interview with The Leunig Fragments Director Kasimir Burgess – on Idols, Filmmaking, and Becoming Michael Leunig’, 13 February 2020, <https://www.thecurb.com.au/interview-with-the-leunig-fragments-director-kasimir-burgess-on-idols-filmmaking-and-becoming-michael-leunig/>, accessed 21 May 2020. Nonetheless, he lets Sunny point to the contrast between the romanticisation of traditional family structures in Leunig’s cartoons and the artist’s inability to maintain his own.

Preserving the veneer

Burgess states that he didn’t have access to Leunig during some of the historical controversies that occurred over the course of filming:

Michael was sort of protecting himself from me and from the public in those moments. He kind of retreats. So, how do you show that? You can suggest those moments and I kind of prefer films that [pose] questions rather than give answers or show things overtly.[9]ibid.

Because Leunig dictated the terms by disappearing for long periods of time, Burgess explains in his director’s statement that he was forced to – almost literally – step into the shoes of his subject, donning a white wig to complete principal photography.[10]Burgess, ‘Director’s Statement’, op. cit., p. 3. But the director also expresses his own reticence to confront or criticise his subject:

You know there were people who kind of wanted me to get closer to Michael and to really see him cry and break him but I was never really interested in doing something that exposed Michael and unravelled him in that […] really personal way. The film celebrates Michael as an artist.[11]Burgess, quoted in Peirce, op. cit.

Ultimately, the documentary is an elegy, one rendered by Burgess and his talented collaborators but essentially stage-managed by its subject. It’s an incomplete version of the artist; true to its title, it is a series of fragments. Considering the mythology and enigma surrounding Leunig, perhaps that’s the best anyone can hope for.

Endnotes

| 1 | Kasimir Burgess, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Madman Films, The Leunig Fragments press kit, p. 3. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See ‘Leunig’s Weaponised Whimsy’, Late Night Live, Radio National, 13 February 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/latenightlive/leunigs-weaponised-whimsy/11955568>, accessed 21 May 2020. |

| 3 | For more on this concept, see Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Paul Foss, Paul Batton & Philip Beitchman, Semiotext(e), New York, 1983. |

| 4 | See Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964, pp. 7–23. |

| 5 | See, for example, Eleanor Robertson, ‘Leunig’s Anti-vaccination Stance Reveals the Fantasy World He Lives In’, The Guardian, 19 August 2015, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/aug/19/i-dont-want-to-go-on-leunigs-anti-vaccination-mental-vacation>, accessed 21 May 2020. |

| 6 | See Ben McLeay, ‘Someone Needs to Check on Leunig Because His Shit Is Getting Real Weird’, Pedestrian, 6 December 2017, <https://www.pedestrian.tv/news/what-gives-leunig/>, accessed 21 May 2020. |

| 7 | See Steve Moffatt, ‘Leunig Quirk Gets a Double Outing’, The Daily Telegraph, 25 September 2018, <https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/leunig-quirk-gets-a-double-outing/news-story/2a36ff83485250cb74105a3fa9d4e43b>, accessed 21 May 2020. |

| 8 | Kasimir Burgess, quoted in Andrew F Peirce, ‘Interview with The Leunig Fragments Director Kasimir Burgess – on Idols, Filmmaking, and Becoming Michael Leunig’, 13 February 2020, <https://www.thecurb.com.au/interview-with-the-leunig-fragments-director-kasimir-burgess-on-idols-filmmaking-and-becoming-michael-leunig/>, accessed 21 May 2020. |

| 9 | ibid. |

| 10 | Burgess, ‘Director’s Statement’, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 11 | Burgess, quoted in Peirce, op. cit. |