There is a growing recognition of Media Studies within education. The Visual Media should be the real consensus point for the content of these courses.

I am not disputing the value of Mass Media Education which concentrates on the structure of mass media, the politics of ownership, ethics of journalism etc.; they are obviously valid. But my growing concern is that the understanding of, and the education in the visual communication modes generated in our society are not being taken seriously enough.

There are some strong advocates for visual education in schools, and probably the most outspoken is David Sless of South Australia. He suggests that “the visual media together form the single largest source of indirect experience in our society”, and strongly advocates a third area of skill in schools, besides literacy and numeracy – what he calls visual thinking. He also suggests that “the focus of visual learning in schools (Art education) has not only failed to educate vision but does not even provide an understanding of contemporary art.”[1]David Sless, “Visual Thinking in Education,” in The Educational Magazine Vol. 35, No. 2. 1978.

Images are mass produced into our everyday world and appear on walls, books, magazines, record sleeves, television screens and even T-shirts. It would seem that we can’t go anywhere without being surrounded by images.

Student Experience

Consider some of the likely visual experiences that individuals in your class have had. They range in magnitude from seeing astronauts on the moon (the live telecast was probably before they were even born) to microscopic views of single cell structures.

The list is endless, and draws on all forms of media; photographs from outer space, x-ray images of the students’ own bodies, photos of their grandparents as children, photos of their town or suburb fifty years ago. Although they may not have travelled further than a hundred kilometres from their birthplace they can readily recognise landmarks and people from all around the world. They could recognise paintings made by artists hundreds of years ago and housed thousands of miles away. Television has enabled students to watch open heart surgery, travel the Amazon, visit opium dens, observe a living foetus in its mother’s womb, watch people being killed in Vietnam or Beirut.

Teaching Practice

But how do we, as Media Studies teachers, use this material?

A 1978 survey of seventy-two Year 6 to Year 9 teachers from twelve randomly selected primary and secondary schools in the Adelaide metropolitan area indicated the following usage of photographs in the classroom.

• For display only (i.e. to make room attractive) 40%

• To stimulate incidental learning (i.e. for motivation) 22%

• To illustrate selected main points 30%

• To elaborate (i.e. to supplement verbal descriptions) 6%

• As a main information source 2%

The conclusions they drew from this were —

It is apparent that photographs are generally used by teachers to simply elicit responses from students which will feed back information already given. This use of pictures may not only contribute to convergent thinking, but it may also deprive students of learning experiences in which they increase understanding through their own observations and interpretations. Considering the potential that photographs have for widening our experience of the world, we could certainly use them for more purposes than simply being attractive appendages to the written and spoken word.[2]What a Picture, Visual Education Curriculum Project, Curriculum Development Centre, Canberra, 1980.

I know it’s still early days in Media Education, but the results of this survey are revealing. It seems to me that the classroom and our established teaching practice offers heaps of untapped opportunities to cultivate visual thinking whether this is in a Media Studies unit or part of any other subject – ranging from Art through the Humanities to Mathematics.

When we teach children literacy skills we engage them in writing activities. It follows that if we want to teach children the visual language of film we should engage them in filmmaking activities. To my knowledge filmmaking has been going on in schools (in Victoria at least) for the past twenty years, so I am not proposing anything revolutionary.

However, I am increasingly wondering if we are not separating out the visual activities.

Visual thinking is not only a recognisable mental process which underlies the activities I have mentioned (painting, sketching, illustrating, photography, film, television and computer graphics) but a part of all intellectual activity and must rank alongside numeracy and literacy.[3]Sless, op. cit.

In my first encounters with teaching filmmaking, a group of students discussing their script said, “We want it to go wobbly and blurry so you will know we are going back in time.” These children learnt that code, not at school, but in front of the screen.

The adults who produce, select, and order the images on the screen are responding to different criteria to those of a child left alone to select and respond visually to the world. By actually making films children can be given the opportunity to make visual selections in accordance with their own responses.

Another very different film I remember was made by primary school children at a busy railway station. Crowds of people were shot from just above knee height – the height of the young filmmakers. This obvious visual reality to a child is outside the normal experience of adult vision, and to some degree illustrates the different criteria with which children respond visually to their surroundings.

The children at the railway station simply related what visually happened. They filmed what they saw and what they responded to. The students who wanted their filming “wobbly and blurry” were responding to their TV viewing experience. They knew what was required and, given half a chance, could remake any of a dozen TV formats. The pity is that they have made no attempt to say anything of their own and unquestioningly accept these visual formats.

Len Masterman, in Teaching About Television,[4]Len Masterman, Teaching and Television, Macmillan, 1980. relates an incident when his class discovered, while making a videotape, a ‘correct’ and an ‘incorrect’ framing for a newsreader. WHERE DO CHILDREN LEARN THESE VISUAL CODES TO BE OBEYED?

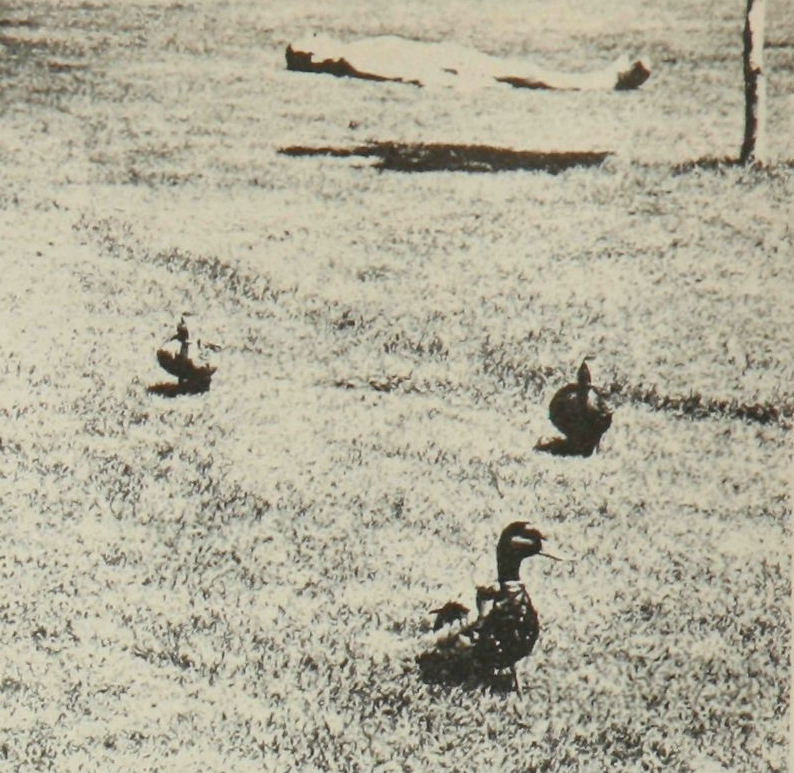

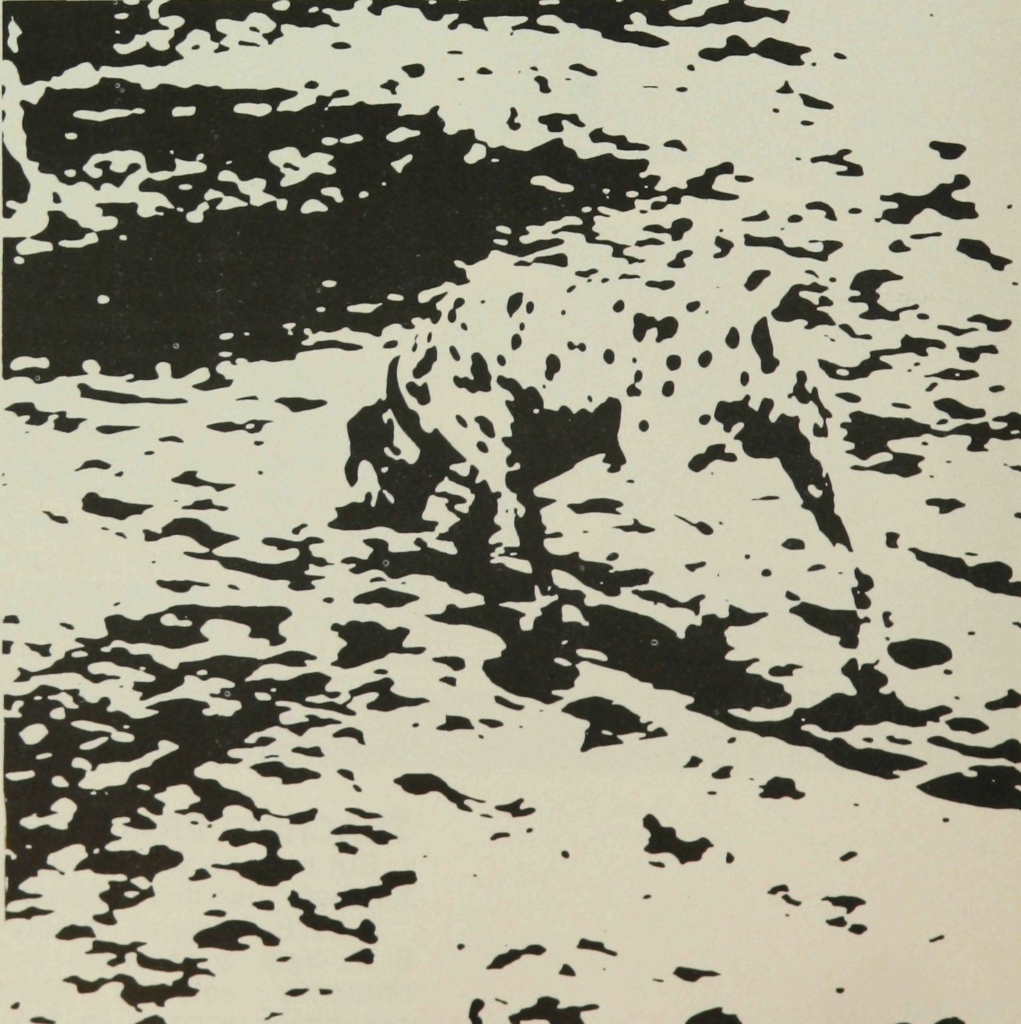

The three ducks in the foreground were obviously the subject of the photo but the reclining person now becomes the dominant interest with an illusion of floating. This effect is even more apparent if you cover the trunk of the tree.

It is not until we look closely for clues from our prior visual experience that we can explain this illusion by identifying the shadow as that of the tree canopy (out of frame) and not of the man. (Photograph: Debbie Mahler)

Eye and Brain

Some understanding of eye and brain needs to be undertaken here.

Although the scientific explanations can be very heavy going, the notion that the eyes are sensory devices which pass images to the brain must be dispelled. Eyes evolved (in all species) as protrusion, but technically are still part of the brain.

Although there is an image projection onto the retina by the lens of the eye, this image is decoded by ganglion cells, each individual cell responding to specific shapes, angles or movement. This coded information is then fed to the brain as impulses. We are therefore faced with the conclusion that vision is a thinking process.

Brief as this explanation is, the point is that there are no pictures in the mind and that the information has been abstracted according to the concepts and assumptions we make when looking at an image.

Obviously we bring prior experiences and assumptions to an image, and when an image is completely outside the realm of experience of the viewer, the brain will interpret within its experience and can also misinterpret information outside this experience.

Body Language

Body language is an area of visual communication which has had comparatively little attention by educators. John Debes in his paper on “Foundations of Visual Literacy” points out that a child not only learns to read body language, but by the age of two has a sophisticated vocabulary,

He (sic) learns to make a face if he doesn’t like his cereal, to squirm if he’s being held too tightly … it is primarily on the basis of body language that the child obtains his whole feeling of happiness and success in dealing with his world. This language is primarily visual so his pattern of dealing with his world and his sense of success in it is primarily visual. This must be so because he has almost no words to use at this time.

Debes goes on to quote John Holt in How Children Learn who said,

The way to educate a child is to find something in which he is interested and something at which he has succeeded and give him more opportunities to succeed in directions in which he has already moved.

Debes suggests that educators seem to do almost the opposite, rejecting visual communicating techniques and insisting on the verbal, when quite often it is the visual that the child has had more success with.[5]John Debes, “Some Foundations of Visual Literacy,” in Audiovisual Instruction, November 1968.

Context

Another important contribution is the context in which an image is seen. On a mantle piece in someone’s home, in a photo album, in a commercial photographer’s window the meaning of a wedding photograph changes. On a billboard, depending on the accompanying type, it could be advertising anything from family planning to home loans.

In a gallery, in a local newspaper, in a national newspaper, or as a photo within a photo (film frame), with each shift the photo is contextualised and influences how we process the visual information.

A simple lesson which student teachers and myself devised involves the pupils viewing a series of slides and then indicating such things as;

• who took the photo?

• for what purpose?

• where was the photo displayed?

• when was it taken?

• and so on.

The images we use range from studio wedding photographs, snap shots, advertised photographs, post cards, printed photos from travel brochures, fashion magazines, and junk mail (the K-Mart sales brochure contains about 280 colour photos and 60 black and white).

As the lesson progresses the photos become more and more ambiguous; this results in some illuminating class discussions where students begin to search for and decode the visual clues they need in order to support their interpretation of the content.

At the last National Conference in Adelaide Len Masterman demonstrated a similar activity where students were asked to identify 30 sec. segments of mute TV programs. They had no difficulty in identifying the ‘genre’ and could quite readily distinguish between TV news interviews and current affairs interviews.

Whereas in the first exercise which I use with student teachers photographs viewed out of context are often not recognised for what they are, in the second instance students quickly identify the content because the context (the TV screen) is constant.

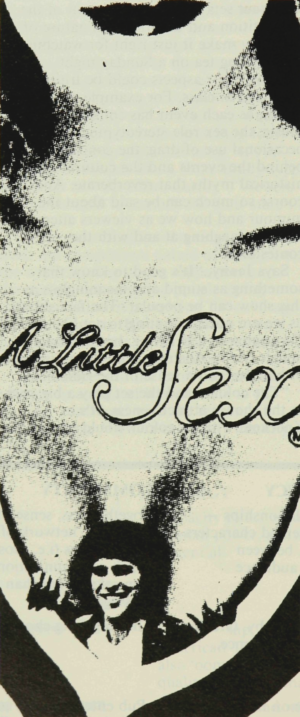

Advertisements

Probably the most sophisticated visual communication operating in our society is that produced by advertising agencies. TV ads and magazine ads often operate on the visual assumption that if one buys the product a luxurious world can be obtained by the consumer. More particularly for adolescents, there is the attainment of peer group acceptance.

The advertising industry actually goes further and claims “only advertising has enabled us to enjoy such a high standard of living as we do today”; “without advertising the public wouldn’t be informed about a wide range of products”.[6]Harry van Moorst, “A Case Against Advertising” in Barr, T., Reflections of Reality, Nelson, 1980.

So the next time you hear “It’s the newest thing there is so get into milk”,[7]Big M TV advertisement. you can thank the advertising industry for informing you of the existence of milk, and at the same time identify yourself as in a wonderful world full of young, sexy milk drinkers.

Acknowledged as one of the most successful advertising campaigns in Australia, it is interesting to look at what the Big M marketing people have actually done. In essence they have ‘packaged’ the product to make it more acceptable to teenagers. Milk becomes Big M, a symbol that is synonymous with a world in which everyone is beautiful, carefree, has a boy/girl friend bought with Big M, and enjoys life to the full – a Utopia.

While not wishing to sound a too cynical campaigner against advertising (I certainly enjoy most ads!) I am suggesting that these compact, sophisticated visual messages are excellent starting points for classroom analysis. As visual modes of communication they operate at various levels of visual consciousness.

A useful class activity is to collect photographs used in magazine advertisements. If the information referring to the actual product is deleted, the students can, by attempting to guess the product, easily start to identify the implied messages being conveyed visually. For instance cigarette advertisements often depict outdoors and fresh air, a subtle counter to the health hazard of smoking. You, and your class will quickly identify many more.

One of my favourites is an image I have collected of a woman in bed, surrounded by film cans, notes, actors’ resumes, and photographs. She is reading what appears to be a film script. Although there is usually little dispute that the woman is an actress or film producer, very few can guess that the advertisement is for sheets. Another sheets advertisement reproduces firstly a painting of well-known and successful women followed by full colour photographs of the subject in the ‘actual’ and ‘intimate’ environs of the portrait.

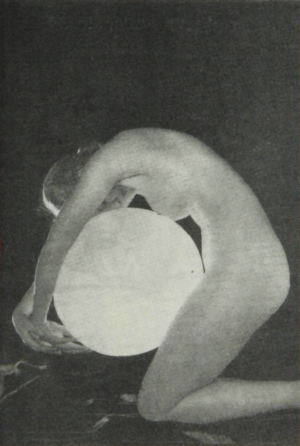

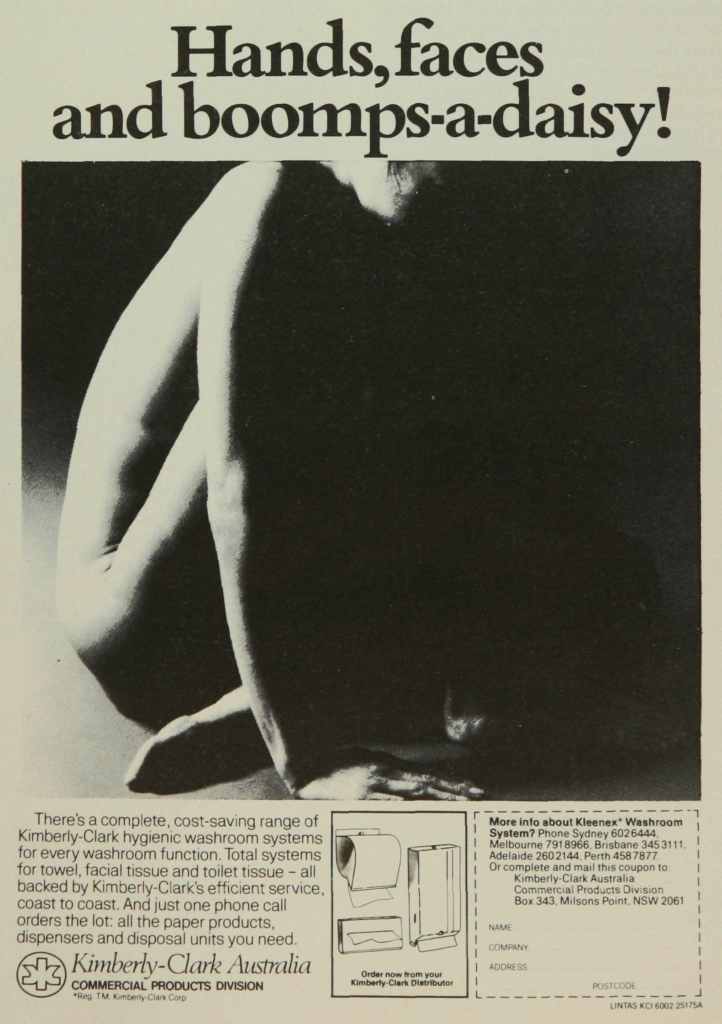

Another is a black and white photograph of a nude woman posed in such a way that the concerns of the photographer are obvious – a sophisticated visual concern for light, form and subsequent abstract composition. However the accompanying caption, “Hands, faces and boomps-a-daisy!” invites the reader to the written text which expounds the advantages of installing toilet paper and paper towel dispensing systems.

This ad poses some interesting questions. What is the target audience? If it is the head cleaner why such a sophisticated image? An important aspect to point out to the students is where the ad was published. For instance, the ad for the sheets was in Vogue Living and/or Belle and/or Home Beautiful; the paper towel ad was in The Bulletin. A collection of ads for the same product, advertised in a range of magazines with different target audiences, often reveals different approaches.

An interesting article to read is: “Photography, Ideology and Education”, Terry Dennett and Jo Spencer, Screen Education, No. 21, Winter 1976/77.

They relate their experiences of a teaching program with inner London teenagers, some of which are based around their approach to ‘found’ photographic images.

Summary

In Australia there appears to have been a fairly general philosophy common to all Media Studies teaching, and that is to learn by doing. Consequently filmmaking, photographic practice, television production and newspaper production have been the bread and butter of many media studies courses.

This I believe is integral to the function of visual education. The most efficient way of teaching is to give students the opportunity to record and arrange their own visuals in an order or context of their own choosing.

What the camera operator chooses to include or exclude in framing reflects response (or bias). An editor can reorder the shots to imply meaning not readily apparent. A sub-editor can caption, crop and position photographs on a page, manipulating meaning.

By actually confronting the problems of shooting and cutting a film, or laying out a publication, students learn how meaning can be changed or implied. Ideas such as setting tasks for students which involve them in creating deliberate bias can ensure that they explore these manipulations. One good activity is to have a group of students make a film, video, audio-visual or publication which presents their school as the best in the State. Other groups of students produce very different points of view, ranging through to, perhaps, the worst school in the State.

In this way we are incorporating the doing with learning media theory. Students must be given the opportunities to use the visual communication modes to effect and not just to emulate last night’s TV programs. There must be understanding of how the visual communication modes operate or we will become hooked on pictures, believing them to be unchallenged reality. As a recent Australia-wide survey disclosed, 67% of people see television news as more reliable than newspapers because you can actually see the news happening.

If seeing the news happening now means that ‘live to air’ is more newsworthy, regardless of content, than a news item that hasn’t any pictures, then reading the news (in every sense of the word) must give a very different picture.

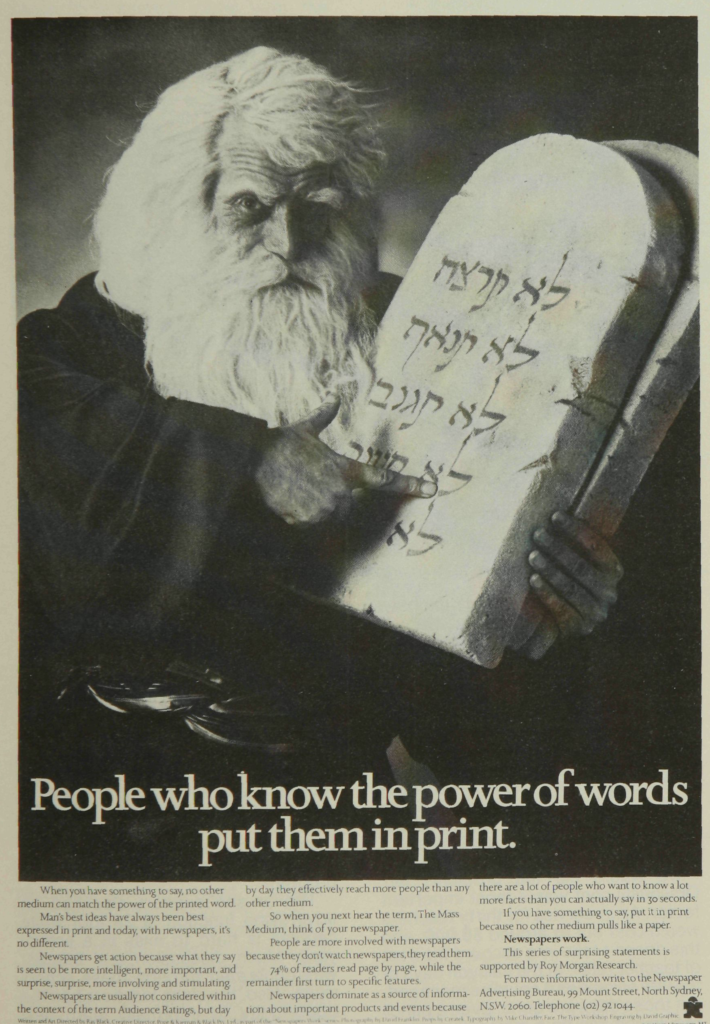

In conclusion, I would like to draw your attention to an ad placed by the Newspaper Advertising Bureau: “People who know the power of words put them in print” captions a full page, broadsheet ad dominated by a photograph, 40cm × 46cm. It would appear that people who know the power of words have more confidence in gaining your attention with a picture.

Bibliography

The following texts are useful background reading to approaches in photography.

Articles

Bethal, A., in Screen Education No. 41 Winter/Spring 1982.

Wartofsky, U., “Cameras can’t see, representation, photography and human vision,” in Afterimage, April, 1980.

Walker, J., “Context as a determinant of photographic meaning,” in Camerawork, No. 19, July 1980.

Mann, S., “Family Snapshots,” in Camerawork, No. 12, January 1979.

Dennett, T., & Spence, J., “Photography, Ideology & Education”, in Screen Education, No. 21, Winter 1976/7.

Sless, D., “Photographic Meaning, an introduction for teachers,” W.P.O.P. 1981, issue 8.

Berger, J., Ways of Seeing, Penguin, London, 1972.

Masterman, L., Teaching about Television, Macmillan, 1980.

Books

Scharf, A., Art and Photography, Penguin, 1974.

Gregory, Eye and Brain, World University Library, 1973.

Sless, D., Visual Thinking, Radio University 5UV, Adelaide, 1977.

What a Picture, Curriculum Development Centre, Canberra, 1980.

Greenhill, Murray, Spence, Photography, McDonald Guidelines, 1977.

Taylor, Hands On, a media book for teachers, National Film Board, Canada, 1977.

Evans, H., Pictures on a Page, Heinemann, 1978.

Bethell, A., “Eye Openers – A Photo Essay” in Screen Education No. 41, Winter/Spring 1982. A review of teaching material since published by Cambridge

Endnotes

| 1 | David Sless, “Visual Thinking in Education,” in The Educational Magazine Vol. 35, No. 2. 1978. |

|---|---|

| 2 | What a Picture, Visual Education Curriculum Project, Curriculum Development Centre, Canberra, 1980. |

| 3 | Sless, op. cit. |

| 4 | Len Masterman, Teaching and Television, Macmillan, 1980. |

| 5 | John Debes, “Some Foundations of Visual Literacy,” in Audiovisual Instruction, November 1968. |

| 6 | Harry van Moorst, “A Case Against Advertising” in Barr, T., Reflections of Reality, Nelson, 1980. |

| 7 | Big M TV advertisement. |