For Nicholas Chare

Ode to Oz

Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986) was inspired by an interview that bushman Rodney Ansell gave to Michael Parkinson in 1981, in which he detailed becoming stranded on the Victoria River in the Northern Territory in May 1977. Ansell’s boat capsized and he was forced to live off the land while waiting for the start of the wet season, which would provide him with the opportunity to hike to safety. By chance, however, stockmen working in the area rescued him. Paul Hogan saw the bushman’s account of his travails, and the comedian subsequently wrote a film script in collaboration with John Cornell and Ken Shadie, using Ansell’s adventures as a starting point. The script, ‘Crocodile Dundee’, detailed the exploits of a character named Michael J ‘Crocodile’ Dundee, also known as Mick Dundee. Hogan, the driving force behind the film, secured the services of Peter Faiman as director. Faiman had previously worked with Hogan as director and producer of the popular comedy The Paul Hogan Show.

Crocodile Dundee was conceived as an attempt to break into the American film market. It therefore formed part of a long line of efforts to crack the US, which began with the early Australian motion picture Uncivilised (Charles Chauvel, 1936). Uncivilised adopted a Tarzan-like storyline about a white man, Mara (Dennis Hoey), who is chief of an ‘Aboriginal tribe’ living in a remote community ‘somewhere’ in the Top End, and a novelist, Beatrice Lynn (Margot Rhys), who ventures into the region looking for inspiration for her next book. Crocodile Dundee, as will become clear, shares some similarities with this film; it, too, has a powerful white ‘wild’ man as king of the bush and involves the arrival of a young female reporter looking for a story.[1]Jeanette Hoorn, ‘White Lubra/White Savage: Pituri and Colonialist Fantasy in Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised (1936)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, 2005, pp. 48–63. Hogan secured funding for the film under a special modification of the federal Income Tax Assessment Act called Division 10BA, which involved substantial tax breaks. The film, however, had to have overseas appeal to please its investors.[2]For a discussion of the impact of 10BA on the form taken by Crocodile Dundee,see Meaghan Morris, ‘Tooth and Claw: Tales of Survival and Crocodile Dundee’, Social Text, no. 21, 1989, pp. 105–27.

The storyline involves action in both Australia and the US, and the cast secured for the feature involved a studied mix of Australian and American actors. The most high-profile American was Michael Lombard, who had had previous success on television in the series Filthy Rich. Hogan was famous through television: his program, which ran weekly, had made him a household name in Australia. John Meillon, who plays Walter Reilly in Crocodile Dundee, was a veteran actor from both the stage and television, and a favourite with Australian viewers. David Gulpilil, who plays Neville Bell, was certainly the most high-profile Indigenous actor in the country at that time, following his appearance in a range of iconic films including Walkabout (Nicholas Roeg, 1971), Storm Boy (Henri Safran, 1976) and The Last Wave (Peter Weir, 1977).

Filming commenced in 1985. The shooting in Australia mainly took place in McKinlay in Queensland and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory. Filming in the US took place in a variety of locations in New Jersey and New York. The film was released in Australia in April 1986 and in the US in September of that year.

Genre bender

The central storyline is the developing romance between the American investigative reporter Sue Charlton (Linda Kozlowski) and the subject of one of her stories, Australian bushwhacker and crocodile hunter Mick Dundee (Paul Hogan). Sue travels to the outback town of Walkabout Creek to meet Mick. It is during this expedition, which involves various adventures including an encounter with a crocodile, that romance blossoms between the reporter and the bushman. At the end of their outback adventure, Sue invites Mick, who professes to have never visited a city, to return to New York with her. In the US, Mick meets a rival for Sue’s affections, newspaper editor and long-time boyfriend Richard Mason (Mark Blum), who, noticing the arrival of competition, promptly proposes marriage to the New Yorker. This leads Mick to believe his affections are unrequited and he resolves to ‘go walkabout’. Sue, however, realises her mistake and manages to track the bushman to Columbus Circle subway station, where Mick, in a famous scene, imitates a sheepdog herding a flock in the outback, trampling over the shoulders of commuters to reach her. Crocodile Dundee is, therefore, a classic romance. Love is able to conquer all, particularly the protagonists’ significant class and cultural differences. The film is usually described as a comedy – it is listed as an adventure and a comedy on IMDb – and its comedic elements have somewhat isolated it from criticism. Stephen Crofts argues that, in the film,

the political is defused or glossed over by the humour, by the romantic coupling, and by the populist tale of upward mobility: Australian outback noble savage wins daughter of media magnate from the world’s media capital.[3]Stephen Crofts, ‘Cross-cultural Reception Studies: Culturally Variant Readings of Crocodile Dundee’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 1992, p. 221.

What follows in this essay is an attempt to look beyond the manifest humour of what is an enduringly funny film and examine three key, often interrelated, themes that are given serious attention in Crocodile Dundee: gender, ethnicity and modernity.

The film’s key themes are played out against the backdrop of a romantic comedy, but the film also encompasses elements from genres beyond this hybrid. Crocodile Dundee is, in many respects, a western. In it, the badlands of Dakota and breaks of Missouri are substituted with the wetlands of the Northern Territory, instead of brown bears there are crocodiles, and Indigenous Australians replace Native Americans – ‘blackfellas’ standing in for ‘injuns’. Mick, his stockman’s hat paralleling the Stetson, is the bushman as frontiersman. The Northern Territory is the Wild West. This relationship is established cinematographically, as long shots linger over the scenery so that setting becomes subject. The sandstone plateaus of Arnhem Land replace the western’s staple shots of mountain ranges and plains.[4]Siegfried Kracauer, Nature of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, Dennis Dobson, Oxford, 1960, p. 282. Russell Boyd’s cinematography conveys the awe-inspiring immensity of the landscape and of nature, which effectively assume an uncredited role in the film. The big country acts as an unruly entity that needs to be conquered and subdued, and forms the proving ground for a particular expression of masculinity.

Wardrobe malfunctions

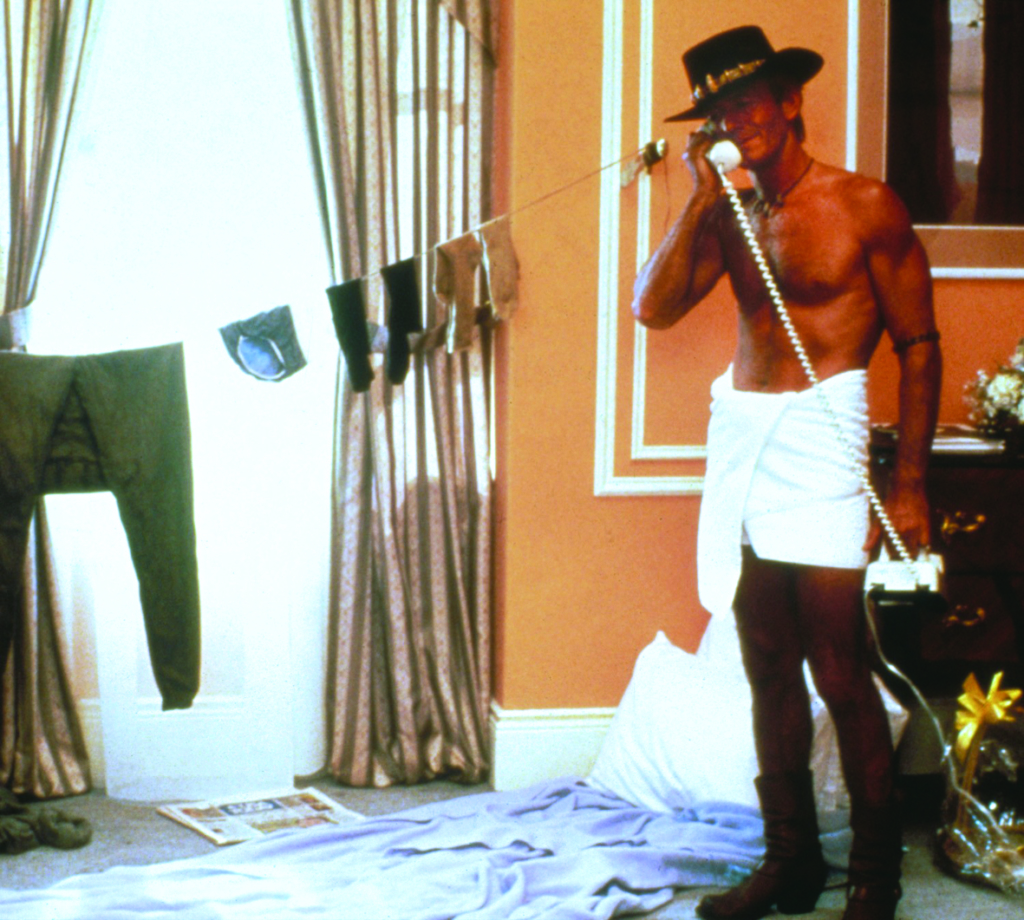

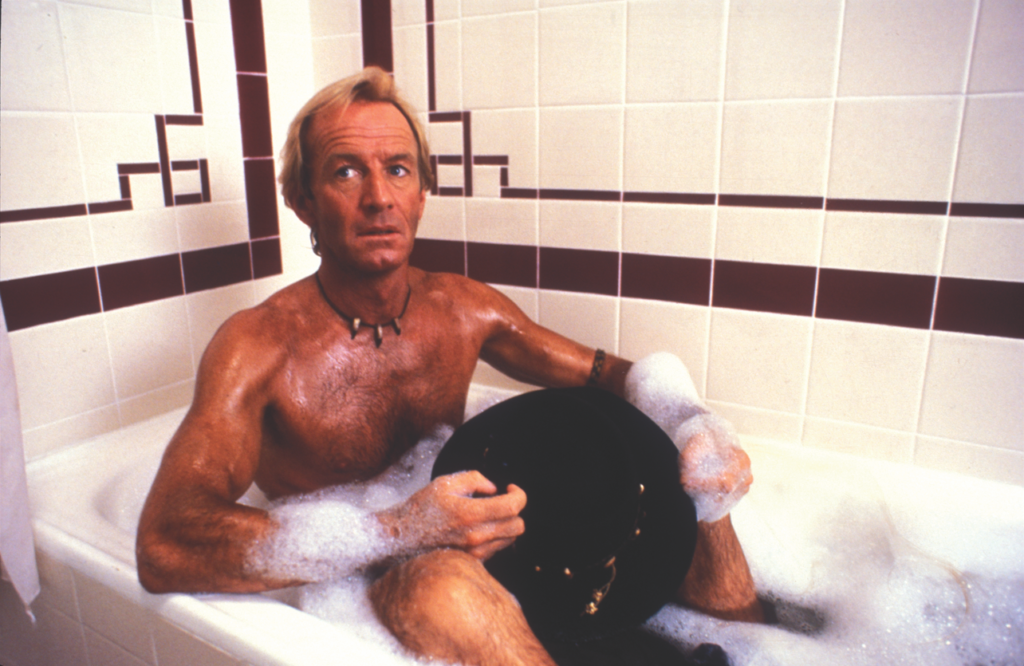

Mick’s appearance, including his attire and physical comportment, forms a crucial marker of his identity. In the Australian scenes, his outfits function to buttress his bush and cowboy credentials. Since the nineteenth century, men working in rural Australia have adopted clothing such as ‘boots, broad belts and open-necked shirts to emphasise their physicality’.[5]Margaret Maynard, Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, p. 173. Mick epitomises this tradition, sporting a wardrobe that appears designed to showcase his lean, bronzed physique. His darkened skin, frequently displayed, visibly attests to a life led outdoors. Backwoodsmen, however, often also exhibit excessive facial hair as it carries ‘explicit overtones of masculine strength’.[6]ibid. Mick, by contrast, is clean-shaven. The potential dent in his potency that this might cause is counteracted in a scene in which he is shown seemingly dry-shaving with a bowie knife. This act draws attention to his body hair (thereby affirming his male potency) while also explaining its lack. In this scene, Mick is shown to have a safety razor tucked in his waistband; the use of the knife is ‘just for appearances’, a clear form of self-presentation. He uses it in an effort to convince Sue of how rough-and-ready he is, but by this stage, she is fully aware of his theatrics.

Crocodile Dundee is, in many respects, a western. In it, the badlands of Dakota and breaks of Missouri are substituted with the wetlands of the Northern Territory, instead of brown bears there are crocodiles, and Indigenous Australians replace Native Americans.

Sue is, of course, also engaging in practices of self-presentation. Her garb on the outback expedition evokes someone on safari rather than bushwalking. She is, though, suitably prepared for the terrain and does not seem overly intimidated by the surroundings. Sue’s physical comportment – her confidence and poise – marks her out as a third-wave feminist. This reporter comes across as assertive and in control; in the initial stages of the journey into the bush, she is as self-assured as Mick. This air of independence is, however, ultimately mere performance masking the reality of her masculine dependency. Sue’s masquerade is revealed when Mick saves her from a crocodile attack and she, overcome by fear, collapses in his arms. This incident is designed to demonstrate the perceived fallacy of the idea that women are equal to men. The outback is bolstered as man’s country. It is noteworthy that, prior to the attack, Sue has stripped down to a swimsuit. Her dress – her undress – at this point symbolically prefigures the stripping bare of her feminist credentials that will shortly take place. Sue, who is being spied on by Mick as she disrobes, is reduced to a source of visual pleasure, powerless to resist a male gaze that she is not aware is there.

In situations in which she is alert to the company she will be keeping, Sue is not above exploiting her sexual appeal. She is more than willing to make use of what Catherine Hakim has described as ‘erotic capital’[7]Catherine Hakim, Honey Money: The Power of Erotic Capital, Allen Lane, London, 2011. to get her way and get her man. This is most obvious in the party sequence in New York (largely shot to the strains of the Australian band Mental As Anything’s ‘Live It Up’). The sequence begins with a young woman dressed in a black two-piece outfit decorated with white alphabet letters that leaves her slender midriff exposed. This midriff, seen in close-up, becomes the camera’s focus for several seconds. It highlights a noteworthy feature of the film: its highly obvious eroticisation of skin. As Nicholas Chare has discussed, the sexual import that skin assumes in this scene is reminiscent in scope, if not in tenor, to that in Cruising (William Friedkin, 1980), one of the few other films to accord the cutaneous its erotic due.[8]Nicholas Chare, Sportswomen in Cinema: Film and the Frailty Myth, I.B. Tauris, London & New York, 2015, pp. 121–2. The other film to remark on in this context is The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993), in which a small patch of skin visible through a hole in some stockings becomes the focus of desire. Crocodile Dundee’s party scene represents a superabundance of skin to which Sue’s striking dress contributes. Her full-length, figure-hugging red cocktail gown, Chare has pointed out, prefigures the black Versace dress that Elizabeth Hurley famously wore to the premiere of Four Weddings and a Funeral (Mike Newell, 1994). This seductive outfit has several missing panels down one side, revealing exposed patches of skin. It is obvious the dress grabs Mick’s attention, most notably when Sue is dancing. The sequence is, in fact, refreshingly frank in the openness of its depiction of the desiring male gaze – of Mick’s repeated ‘eyeing up’ of the women around him. At the party, as in the outback sequences, the reporter is coded as a femme fatale. In New York, she uses her sexuality as a weapon while, in the bush, she had threatened to emasculate Mick through her defiant independence. (The bushman’s killing of snakes here takes on Edenic connotations.)

The contrast between Mick and Richard is strongly established through differing choices of male apparel. This is given its most forceful expression in the first encounter between bushman and city slicker, which takes place at Newark airport. Richard is initially shown waiting in the arrivals hall, leaning against a revolving billboard that is advertising the multinational technology brand Fujitsu. The words ‘for business in search’ from the advertisement are clearly visible behind him, and he is wearing a double-breasted suit, a shirt and a tie. His clothing, coupled with the advertisements that surround him, function to code Richard as a businessman, even though he is actually a newspaper editor. Richard’s ‘look’ of corporate couture would not be out of place in Wall Street (Oliver Stone, 1987). He is also bespectacled, and his glasses, as prostheses, draw attention to the inadequacy of his eyesight. In contrast to Mick, who appears to have 20/20 vision, Richard is thus depicted as physically lacking from the word go.

Mick arrives in the US wearing the same style of clothing he sported in the outback: a felt hat adorned with crocodile teeth, a crocodile-skin vest, a cotton shirt, jeans and cowboy-style boots. That some of Mick’s clothing is manufactured out of materials from the bush implies that he embodies the bush; his dress acts as a powerful visual marker of his difference from the city-dwellers that surround him. Having changed for dinner shortly after arriving in New York, Mick’s necklace of teeth is still plainly visible around his neck. The use of teeth in what is now referred to as jewellery has a long history. In Australia, traditional Indigenous cultures have often worn necklaces incorporating animal fur and teeth,[9]Anna Edmundson & Chris Boylan, Adorned: Traditional Jewellery and Body Decoration from Australia and the Pacific, Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1999, p. 10. which are seen as spiritually charged adornments. Given the proximity to Indigenous culture that Mick manifests in the outback, it is not unreasonable to presume that the jewellery possesses a similar significance to him and is not solely used as decoration. Mick is bound to the country; Richard, by contrast, is a creature of the city.

As the action in New York develops, Richard is represented as at once an urbane, multilingual sophisticate and a fawning, self-absorbed, two-pot screamer. The editor is shown to be a ‘man about town’, while Mick is the real man in Uptown. The newspaper editor’s emasculation is given its fullest expression when he is shown as unable to handle his drink. The importance of prodigious alcohol consumption as an indicator of masculine accomplishment is established early on in Crocodile Dundee in the scene of the spit-and-sawdust pub known as the Walkabout Creek Hotel. Beer is the drink of choice in such watering holes;[10]Recognising the importance held by ale in many an Australian male psyche, Bob Hawke, the prime minister of Australia at the time Crocodile Dundee was released, used to make much of his beer-drinking prowess, regarding it as an election asset. The enduring importance of this aptitude in some quarters of Australia is demonstrated by the wide reportage of Hawke’s ability to scull a beer at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 2012. tellingly, however, Richard is shown getting drunk on vodka martinis at the restaurant.

Cocktails are culturally coded as a drink for women and the upper classes; they are a ‘soft’ drink. Though Mick is shown ordering two of them with his beer, ostensibly out of ignorance, it nonetheless reinforces his skill for alcohol consumption. Richard is subsequently driven home, lolling and flopping in the back of a limousine, feeling nauseated. His flaccid physical comportment here contrasts strikingly with the still-upstanding, steadfastly lucid Mick. In the film, Richard fails to live up to his stoneworker surname. He is too soft; it is Mick who is cast as the hard man.[11]For a discussion of hardness as a masculine attribute, see Nicholas Chare, ‘Getting Hard’, in Adam Locks & Niall Richardson (eds), Critical Readings in Bodybuilding, Routledge, New York, 2012, pp. 199–214. This is particularly the case in the international release of the film, from which an earlier scene in Australia of Mick sprawled drunk in the back of a ute was cut.[12]For an analysis of many of the differences between these two releases, see Stephen Crofts, ‘Re-imaging Australia: Crocodile Dundee Overseas’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 1989, pp. 129–42.

Tribal fantasies

As already discussed, Mick’s sense of dress, particularly the necklace he wears, demonstrates the connection he strives to cultivate with the Northern Territory’s Indigenous people and with the land. Sue asks him directly about Aboriginal land rights during their bush adventure, but the bushman suggests such a discussion is a non-starter because Indigenous people do not have a perception of land ownership. Advocating such an idea of Australia as terra nullius until the arrival of the Europeans is untenable, of course. The Black War between the Indigenous population of Tasmania and its colonists, for instance, demonstrates that the native population was both territorial and proprietorial in relation to resources, and the contemporary land rights movement is testimony to the importance of country to Indigenous Australians. But Mick’s view reflects common assumptions held prior to the High Court’s Mabo decision in 1992. The film as a whole is engaged in a complex and not always constructive dialogue with Indigenous Australia. In this context, it is notable, for example, that the first Indigenous Australian whom Sue (and the viewer) encounters is disturbingly introduced with a knife held to his throat. This man turns out to be Neville, a friend of Mick’s, who is on his way to visit his father at a corroboree. Gulpilil, who plays Neville, had previously acted in a range of serious roles in which he represented aspects of Indigenous Australian spirituality, and he surprised Australian viewers here by sending it up.

Mick is, at times, with varying degrees of success, constructed as striving to ‘pass’ as Indigenous, but this passing often has satirical overtones. That it is played for laughs is clear in the scene at Echo Billabong, which plainly echoes a scene from another film set and shot in the Northern Territory, Jedda (Charles Chauvel, 1955). In Jedda, Indigenous Australian Marbuck (Robert Tudawali) is shown catching a fish in a billabong. He then cooks it and shares it with the eponymous Jedda (Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, credited as Ngarla Kunoth). Mick similarly spears a fish and, earlier in the same sequence, cooks goanna for Sue, but rejects the opportunity to eat this meal. Having proved himself as hunter-gatherer, he opts for a tin of baked beans instead, describing traditional Indigenous foodstuffs as tasting like shit. The goanna, accompanied by grubs and yams, is another prop to aid his performance as proficient bushman. That this is mere show, rather than a demonstration of Mick’s understanding of the Indigenous relationship to the land, is obvious from the wanton extravagance displayed.

Comparing Jedda and Crocodile Dundee is also informative in relation to the fights with crocodiles that occur in the two films. Mick and Marbuck both use knives to battle with these giant reptiles: Marbuck uses a small stone knife, while Mick uses a big metal one. Marbuck’s battle is lengthy, and leaves him exhausted. Mick’s is brief, and leaves him barely needing to catch his breath. The comparison gives a sense that anything an Indigenous Australian can do, Mick can do better. This is made explicit in the film when Neville leaves Mick’s camp to go to the corroboree. Sue asks how he can find his way in the dark, and Mick explains that ‘he thinks his way’. Shortly after this, however, we hear Neville collide with something and swear. When Mick follows Neville into the darkness shortly afterwards there is no suggestion that he encounters any obstacles. He evidently ‘thinks his way’ better.

Sound is, in fact, one of the key ways in which Mick’s connection to Indigenous Australia is articulated and cemented. This is clearest in the scene in which the bushman subdues a buffalo by employing what Walter describes as ‘mind over matter’. Ruth Abbey and Jo Crawford have noted that

in this scene didgeridoo music is heard in the background, so that this portrayal of Mick Dundee serves to depict him as being the repository of the ‘special relationship’ with the natural environment that has traditionally been attributed to aborigines.[13]Ruth Abbey & Jo Crawford, ‘Crocodile Dundee? Or Davy Crockett?’, Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 23, no. 4, 1990, p. 159.

This scene forms the beginning of a steady transformation in Sue’s view of Mick – from charlatan to shaman, someone in possession of otherworldly abilities. The bushman’s larrikin dissembling appears to conceal hidden depths. Like Tarzan in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novels, he can talk to the animals – command them – and he is represented as possessing attributes of the crocodile. He describes the injury he received from the reptile as a ‘love bite’, implying intimacy between man and animal, and he also tells Sue that, like the saltwater crocodile that attacked her, he too has considered ‘eating her alive’, which suggests identification with the beast. For the international release of the film, inverted commas were added around ‘Crocodile’ as a means to make it clear to the marketer’s fantasised audience that the film was not about a crocodile called Mick. This may ultimately have been misleading.

The relationship between Mick and the Indigenous population is more prominent in the international release of the film. When Mick drives Sue and Walter into the outback, the reporter questions him on his past, and he reveals that he was raised by a local tribe. In the Australian version of the film, however, it is Walter who makes this claim (as part of a subsequent scene excised from the international release). He is roundly rebuked by Mick, who claims that no such thing took place and that he actually endured an itinerant childhood being ferried between different relatives. The international audience was therefore presented with a stronger rationale for Mick’s deep affinity with Indigenous culture. This explanation was presumably deemed unsuitable for an Australian audience familiar with the issue of the Stolen Generations, although Mick still claims to belong to a tribe when he is conversing with Gus (Reginald VelJohnson), the uniformed chauffeur in New York. Despite the different childhood accorded to Mick for the film’s domestic audience, his kinship with Indigenous Australians is firmly cemented by way of his attending a corroboree. This enables him to be seen as a ‘tribal initiate’ and a ‘white Aborigine’.[14]Morris, op. cit., p. 117.

The New York setting puts black masculinity in dialogue with Australian Indigeneity. If Neville represents the Other in Australia – the person against whom Mick’s identity is to some extent constructed there – then the character of Gus fulfils an equivalent role in the US.

In the second half of the film, the New York setting puts black masculinity in dialogue with Australian Indigeneity. If Neville represents the Other in Australia – the person against whom Mick’s identity is to some extent constructed there – then the character of Gus fulfils an equivalent role in the US. It is telling that, when Gus is first introduced, he is out of focus and in the background. The lack of pictorial resolution can be seen to figure unresolved tensions in relation to black masculinity as a whole within the film. Gus is labelled as Indigenous by Mick, who refers to him as both a tribesman and a ‘blackfella’. This echoes a scene in Tarzan’s New York Adventure (Richard Thorpe, 1942) in which Tarzan identifies a black hotel valet as a tribesman.[15]Morris recognises this source; see ibid., p. 120. Unlike this valet, however, the chauffeur is at least given the right to reply and is initially, at least partly, unwilling to support the bushman’s characterisation of him, stating emphatically: ‘Man, I ain’t from no tribe.’ He does, however, concede that he is a ‘blackfella’. Despite this, he later appears to confirm Mick’s assumptions in their entirety when he uses the limousine’s boomerang-shaped car-phone aerial as a flying weapon in order to knock out a criminal, and then states that the tribe he belongs to is the Harlem Warlords. Garry Gillard reads this scene as a ‘neat mirror-image of the earlier presentation of Neville as an urbanized blackfella’.[16]Garry Gillard, ‘Like a Tarzan Comic: Crocodile Dundee’, Screen Education, no. 44, 2006, p. 128. If this interpretation is accepted, then both Neville and Gus are constructed as characters unable to integrate fully in the city. Their ‘tribal’ roots – the ‘uncivil’ aspects of their character – will always ultimately manifest themselves. They are never merely urbanites; their ethnicity is always also foregrounded.

The repeated framing of Mick as a Tarzan-like character helps to sustain this interpretation: Richard refers to him as ‘Jungle Jim’; a sex worker, Karla (Nancy Mette), describes him as ‘a regular Tarzan’; and Sue asks him why he always makes her ‘feel like Jane in the Tarzan comics’. This last reference occurs after Mick has seen off a would-be mugger at the subway station exit of the Manhattan Municipal Building. This scene, one of the most memorable in the film, repays careful viewing. Sue and Mick are confronted by a gang of three youths. Their black leader threatens the bushman with a switchblade and demands his wallet. Mick then pulls out his bowie knife, declaring: ‘That’s not a knife – that’s a knife!’ He slashes the sleeve of the youth’s red PVC jacket, exposing bare flesh, and the gang retreat. This scene of knife anxiety is, of course, also one of castration anxiety. The castrating potential of Mick’s knife is rendered explicit in Crocodile Dundee II (John Cornell, 1988), when he holds a drug-enforcement officer’s penis hostage with his bowie. In the earlier film, it is only implied: the black adolescent – the black man – is symbolically castrated. Anxieties about manliness and ethnicity intersect.

It is moments after the gang retreat that Sue compares Mick to Tarzan. Her comments reinforce a set of associative links in Hollywood culture identified by Yvonne Tasker ‘between blackness, Africa and images of the jungle’, for which Tarzan films have provided ‘a key point of mediation in cinematic terms’.[17]Yvonne Tasker, Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and Action Cinema, Routledge, London, 1993, p. 50. The knife is Tarzan’s weapon of choice,[18]Marianna Torgovnick, Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990, pp. 64–5. and it embodies his manliness. In Crocodile Dundee, the underlying logic is the same: the bigger the knife, the bigger the man. The film therefore depicts the bushman as both more manly than the debonair Richard and the anonymous hoodlum. The slashing of the criminal’s jacket, however, signifies more than merely cutting his manhood down to size. It also serves to display the man’s body – to emphasise it – which reinforces the idea that black men have traditionally been equated with body and nature, as bell hooks has argued.[19]bell hooks, ‘Feminism Inside: Toward a Black Body Politic’, in T Golden (ed.), Black Male, Abrams, New York, 1994, p. 131.

The black man’s body in Crocodile Dundee is brought back to him in a way that is comparable to the dynamic of a later film, Predator 2 (Stephen Hopkins, 1990), which is also set in an urban jungle. In Predator 2, the ‘civilised’ hero, black police lieutenant Mike Harrigan (Danny Glover), is contrasted with the brutal Jamaican gangsters and the seemingly dreadlocked alien from which the film takes its name. Harrigan wears a suit, which gives him a veneer of white-collar respectability. Ultimately, however, this respectability and civility is a masquerade: the film ends with a bloodied Harrigan, his clothes shredded, his face coated in dust, returned to his ‘rightful’ place. He looks ‘savage’. The grime that coats his visage, reminiscent of clay body paint, is the strongest indicator of his ‘brutishness’. In his exhausted state he also walks stiffly, connoting the zombie. The scene forms the most obvious of several in which Harrigan is associated with images of the ‘primitive’.[20]Tasker, op. cit., p. 50. Crocodile Dundee is more subtle, yet embodies the same structure of revelation. The hoodlum is deprived of the jacket that signals his refinement; he is rendered ‘body’. Gus is made to reveal his ‘tribal’ aspect. The ‘primitiveness’ concealed by the two characters is ultimately uncovered, with Mick as the catalyst. Like Tarzan, he bears traces of the ‘primitive’ but he is also able to circulate in civilised society, whereas Gus and the criminal are forced to exist at its margins. Mick has tamed the beast within. The black men, however, merely appear to have done so.

The shock of the new

Mick’s Tarzan-like persona also enables Faiman’s film to stage an encounter between the pre-modern and the modern. This backwoodsman-meets-city-slicker formula has Australian antecedents in films such as Dad and Dave Come to Town (Ken G Hall, 1938), though the obvious set pieces of Crocodile Dundee’s staging are, in many ways, indebted to Tarzan’s New York Adventure. These include Mick’s encounter with new technology, such as the escalator at Newark airport (presumably there were no escalators in Australia) and the bidet in his hotel room. In Tarzan’s New York Adventure, the apeman is confused by a radio and amazed by a walk-in shower. Crocodile Dundee is, however, more sophisticated in its exploration of modernity’s violence. In his discussion of Charles Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin wrote of the flux of people in a big city, observing that ‘moving through this traffic involves the individual in a series of shocks or collisions’.[21]Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire, trans. Harry Zohn, Verso, London, 1997, p. 132. City-dwellers grow used to these impacts and learn how to avoid them. They are inured to and insulated by the balm of familiarity. Shortly after arriving in New York, Mick endeavours to take a walk and ends up taking to the ‘trees’ – climbing road signs to escape the street-level traffic of New York’s concrete and asphalt jungle. He registers the shock of navigating the city crowd as though for the first time.

Mick strives to greet all those he encounters and to engage many in pleasantries, which displays his small-town upbringing and attitude, and also brings home the alienating effects of living in a metropolis: masses of people pressed together, united in their indifference to one another. There is no bush telegraph in New York, and no evidence presented in the film of the city having strong communities comparable to that of Walkabout Creek. Country living, and the country, is contrasted favourably with the city. The country, as constructed by Crocodile Dundee, is a place of togetherness, exemplifying the ethos of mateship, whereas the metropolis is characterised by disconnection and is a place associated, in the film, with drugs, violence and dissatisfaction.

The main criticism of the modern city – and, by extension, modernity – that the film articulates is that its inhabitants are constricted, exclusive and rootless. The centre of the city is filled with people who are socially excluded by the well-to-do and thus economically marginalised. There are strong class differences that are not apparent in the rural society constructed by Crocodile Dundee – one seemingly untouched by the pernicious effects of capitalism.These differences intersect with race. The black men in the film – Gus (who does not own the car he drives) and the nameless robber – are economically disenfranchised. The society reflected in Crocodile Dundee is thus, in many ways, comparable to that represented in Tarzan’s New York Adventure forty years earlier. There is a telling scene in the Tarzan film in which Cheeta is shown causing chaos at a water dispenser in the airport arrivals hall, littering the ground with paper cups to the amusement of bystanders. Briefly, to the right of the frame, at its margins, a black cleaning attendant is shown waiting to clear up the mess. He must deal with the joke’s debris. The cleaner, like Gus, is a member of the service industry, but with the character of the chauffeur, the walk-on part has progressed into a bit-part role in the Big Apple.

Crocodile Dundee, however, is of a different order to its Tarzan antecedent. It provides a genuine exploration and critique of the contemporary state of interpersonal relations in 1980s America. Mick fosters real affection among many of those who encounter him because his communication with them goes beyond hollow pleasantries and empty commonplaces – the vacuous ‘Have a nice day!’ – that accompany capitalist commodity-exchange culture. He takes an interest in the limousine that Gus drives, and he teaches Irving (Irving Metzman), a doorman, Australian expressions and learns their US equivalents in an educational give-and-take. Irving shows touching sadness when Mick leaves to go walkabout, as the usual platitudes he had exchanged with hotel guests has been replaced by a sense of true connection in his interactions with the bushman. It is through its depiction of these kinds of relations – of which Mick’s friendship with taxi driver Danny (Rik Colitti) is another example – that Crocodile Dundee advances mateship as the founding point for an ethics of interpersonal encounter. The film comments on the breakdown of social bonds between individuals under the current economic system, which is particularly evident in urban environments, and strives to offer a solution.

Crocodile Dundee also equates capitalism and its alienating effects with dislocation. Walkabout Creek is constructed as a community because the outback as a ‘place’ fosters a sense of belonging among the people living there, both to one another and to the land. This belonging arises because the bush is understood as a locale of stasis. The city, by contrast, is portrayed as being in perpetual motion: people are continually journeying and moving between spaces, and are never at rest, arriving or settling. The importance of place to identity is common in Australian cinema, and the countryside often offers locations that are presented as a kind of prelapsarian paradise providing an outside to, and escape from, the harsh realities of contemporary existence. In Tomorrow, When the War Began (Stuart Beattie, 2010), the remote valley of ‘Hell’ belies its name and fulfils this function of refuge in wartime. The Year My Voice Broke (John Duigan, 1987) includes a rocky outcrop that functions as a refuge for the two main characters, Freya (Loene Carmen) and Danny (Noah Taylor). In an early scene, Freya is shown caressing the rock, touching the place that is tied so strongly to her sense of self and to which she often retreats to avoid family pressures.

Mick fosters real affection among many of those who encounter him because his communication with them goes beyond hollow pleasantries and empty commonplaces … that accompany capitalist commodity-exchange culture.

Echo Billabong performs the equivalent role in Crocodile Dundee. The place’s positive significance is clearly established by a shot midway through the sequence at the small lake in which Sue and Mick swim. The camera slowly pulls back; the two figures splashing in the billabong’s turquoise waters gradually recede from view until they are reduced to scuffs of white set against a blue-green backdrop. This shot fades and is replaced by another of the sky so that, for a moment, Sue and Mick briefly appear to be swimming in the heavens. In a film that constantly mirrors scenes of the outback with scenes of New York, there is, revealingly, no equivalent in the city for this idyllic moment.

The difference between the country and the city is demonstrated most obviously by one of the many instances of parallel scenes that structure the film. In New York, Mick is shown on top of a skyscraper, gazing out over the metropolis. Sue takes several photographs to record the moment as the bushman points at the cityscape. This mirrors an earlier scene in which Mick points out the damage to the wreck of his boat while the reporter takes photographs. This earlier gesture is informed by memory and filled with meaning and significance, whereas the later gesture is an empty one. The trip to the viewing platform is pure theatre, staging Mick as a tourist to feature in Sue’s newspaper article about him. Mick points to nothing – he is singling out no detail, and has no connection to the buildings in the distance. There is nothing substantial, other than Sue, that binds him to the panorama. The entire scene bespeaks superficiality. Mick’s fake smile and pose symbolise a more significant shallowness and detachment in the city; in this sense, something is being pointed out.

The scene also involves a moment of distancing, estranging the viewer from the film as semblance of truth by way of arresting on-screen time: there is a freeze-frame of Mick gesturing. This seemingly still image can be seen to represent the photograph Sue has just taken. The click of the analog camera has transformed Mick into a commodity – a spectacle. His outback image will now be used to sell newspapers. It is detached from Mick and from the forward flow of the narrative. This use of editing opens a space for the viewer to develop a critical distance from the film, to reflect on the helplessness of the bushman in the face of the conspicuous consumption that surrounds him.

There is another freeze-frame in the film that should be read in conjunction with this one, as it offers a possible means of escape from the alienating effects of modernity. This stopped motion occurs at the end of the film, when Sue declares her love for Mick in the subway station. It is part of a sequence described by Abbey and Crawford as ‘perhaps Mick’s greatest victory over mass society’.[22]Abbey & Crawford, op. cit., p. 162. The lead-up to the freeze-frame involves Sue running to the station, discarding her high heels along the way, only to arrive and find she is separated from the bushman by a crowd of commuters. She calls out ‘Cooee!’ – hailing Mick in pidgin Dharug and, thus, identifying with Australia for the first time. The reporter then initiates a bush telegraph, asking Mick not to leave and declaring her love via word-of-mouth relay. The bushman responds to this last communication by stating that he will cross the crowded platform to deliver his response in person. A construction worker claims, ‘It’s just too crowded in here. We’re jammed in like sheep.’ For an Australian viewer, the reference to sheep may connote the pastoral,[23]For an examination of the role of the pastoral in the Australian imaginary, see Jeanette Hoorn, Australian Pastoral: The Making of a White Landscape, Fremantle Press, Fremantle, 2007. and Mick’s solution to the problem of being hemmed in is likely to strengthen such an association: he raises himself up and walks upon the heads and shoulders of the commuters in a way redolent of sheepdogs walking over the heads of sheep.[24]Abbey & Crawford, op. cit., p. 162. The station thus becomes a mixture of bush and pastoral, and it is also transformed into a miniature community. Sue and Mick foster connection among the people present, which is given its most potent expression through the spontaneous applause that greets their embrace. This clapping forms a coming-together of those present, acoustically and emotionally. It is for this reason that Veronica Brady has referred to the scene as the victory of mateship.[25]Veronica Brady, ‘Evading History’, Australian Society: A Magazine of Social Issues, vol. 7, no. 3, 1987, p. 34. The freeze-frame that distils the action suggests that more is going on here.

The sequences of the outback offer an anchored and reflective way of interacting with the world, which is at odds with the film’s quick-fire conveyor-belt comedy that offers easy laughing and instant gratification.

The only two freezes in Crocodile Dundee occur in the second half of the film. In terms of the film’s cinematography, these interruptions to the fast-paced rhythm of the American sequences can be understood as echoes of an alternative tempo present in the earlier Australian section. In the footage of the outback, it is sometimes as though the sly beauty of the landscape has crept up on the unsuspecting cameraman. There are certain shots in which the camera lingers over the land, staying behind the narrative.[26]This phenomenon is recognised by Neil Rattigan, who regards it as an attempt to aestheticise the outback; see Rattigan, ‘Apotheosis of the Ocker’, Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 15, no. 4, 1988, p. 150. This occurs, for example, early on, in the sixth shot of the truck that Mick is driving to the bush. The Dodge travels past the camera, which remains fixed in place, continuing to film after the vehicle has passed, recording red dust swirling and dissipating, a dirt track, trees, the sun and the sky. The film’s tarrying in soil and sun does not aid the development of the storyline, nor does it provide a dazzling special effect with which to astonish the audience. These enduring scenes, which are of a different temporal order from the action in New York, fortify a sense of place, as though the camera itself were striving to find somewhere to belong, and briefly succeeding.

These scenic interludes – views that elude verbal description – function in a way that is comparable to Nicolas Poussin’s landscapes for art historian TJ Clark. They are points of opposition to the society of the spectacle – a society in which commodification has colonised social life to such an extent that commodities are now all there is to see.[27]Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone, New York, 1995, p. 29. The visual imagery here, in excess of the film’s narrative and not involved in selling its story, embodies a site of resistance ‘in a world saturated by slogans, labels, sales pitches, little marketable meaning-motifs’.[28]TJ Clark, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing, Yale, New Haven, 2006, p. 123. The cinematography of the land is used in Crocodile Dundee to stand against Times Square – to defy the dislocation and transitoriness of the city, and contest the culture of consumption it exemplifies. The sequences of the outback offer an anchored and reflective way of interacting with the world, which is at odds with the film’s quick-fire conveyor-belt comedy that offers easy laughing and instant gratification. Humour in the film provides meagre compensation for the reality of poor wages and social alienation. Shots of the land, by contrast, exist outside of Crocodile Dundee’s comic timing, inviting serious reflection on changing those circumstances.

Afterimages

Recognised as a landmark of Australian cinema, Crocodile Dundee is also one of Australia’s most successful films in financial terms. It had a budget of A$8.8 million and has so far earned US$360 million worldwide. It was the second-highest-grossing film in the United States in 1986 after Top Gun (Tony Scott, 1986), and therefore fulfilled its aim of breaking into that previously elusive market. The film was followed by two sequels that were also lucrative: Crocodile Dundee II and Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles (Simon Wincer, 2001).

The film also had immense influence beyond the box office. It is credited with providing a significant boost to Australia’s tourism industry, so much so that Australian tourism officials ‘talk about visitor figures in terms of BD or AD; that is, before or after Dundee’.[29]Nichola Tooke & Michael Baker, ‘Seeing Is Believing: The Effect of Film on Visitor Numbers to Screened Locations’, Tourism Management, vol. 17, no. 2, 1996, p. 89. In an example of life imitating art, the Federal Hotel, which was used as the location for the Walkabout Creek Hotel scenes, changed its name to reflect its identity in the film. Crocodile Dundee therefore ably demonstrates how cinema has real effects, and how fantasies on screen can inform reality. It brings home the truth that the boundaries between on-screen and lived existence are permeable. This is fitting for a film that recurrently explores the relationships between reality and appearance, and between fact and fantasy.

Given the film’s tremendous influence, its problematic treatment of issues related to gender and ethnicity demands caution. With hindsight, however, if the film is sexist and racist, it is a tired sexism and racism – an exhausted performance of discrimination. Meaghan Morris draws attention to Mick’s poor imitation of Tarzan’s cry, describing it as a ‘mangled gurgle’;[30]Morris, op. cit., p. 112. the efforts to live up to manly cinematic models of the past are half-hearted. It is telling that Mick gets the girl at the moment when he no longer has possession of his bowie knife, the symbol of his power, and is at his most emotional: hurt, upset and bewildered. Crocodile Dundee can be seen to pose ethnicity and masculinity as questions, and it betrays a commendable honesty in refusing to provide easy answers to them. The final freeze-frame embodies a refusal to offer any simple resolution and foreclosure in relation to the issue of identity politics. It is for this reason that the film, despite its faults, possesses an enduring appeal.[31]I wish to thank Nick Chare – who shares with me a long-term affection for Crocodile Dundee – for the many insights that he has given to me and that appear in this article. I also wish to express my gratitude to Nick for his outstanding contribution to teaching and research in film studies, gender studies and art history at the University of Melbourne.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Ruth Abbey & Jo Crawford, ‘Crocodile Dundee? Or Davy Crockett?’, Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 23, no. 4, 1990, pp. 155–77.

Rod Ansell & Rachel Percy, To Fight the Wild, Currency Press, Redfern, 1986.

Veronica Brady, ‘Evading History’, Australian Society: A Magazine of Social Issues, vol. 7, no. 3, 1987, pp. 33–4.

Stephen Crofts, ‘Cross-cultural Reception Studies: Culturally Variant Readings of Crocodile Dundee’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 1992, pp. 213–27.

Stephen Crofts, ‘Re-imaging Australia: Crocodile Dundee Overseas’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 1989, pp. 129–42.

Garry Gillard, ‘Like a Tarzan Comic: Crocodile Dundee’, Screen Education, no. 44, 2006, pp. 125–8.

Jeanette Hoorn, ‘White Lubra/White Savage: Pituri and Colonialist Fantasy in Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised (1936)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, 2005, pp. 48–63.

Carolyn James, Paul Hogan, St. Martin’s Press, London, 1987.

Sandra Jobson, Paul Hogan: The Real-life Crocodile Dundee, WH Allen, London, 1988.

Rose Lucas, ‘Dragging It out: Tales of Masculinity in Australian Cinema, from Crocodile Dundee to Priscilla, Queen of the Desert’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 22, no. 56, pp. 138–46.

Albert Moran, Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema, Scarecrow Press, Lanham, 2005.

Meaghan Morris, ‘Tooth and Claw: Tales of Survival and Crocodile Dundee’, Social Text, no. 21, 1989, pp. 105–27.

James Oram, Hogan: The Story of a Son of Oz, Columbus Books, London, 1987.

Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London, 1996.

Neil Rattigan, ‘Apotheosis of the Ocker’, Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 15, no. 4, 1988, pp. 148–55.

Neil Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of New Australian Cinema, Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, 1991.

Nichola Tooke & Michael Baker, ‘Seeing Is Believing: The Effect of Film on Visitor Numbers to Screened Locations’, Tourism Management, vol. 17, no. 2, 1996, pp. 87–94.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1986 Length 104 minutes (Australia), 97 minutes (international) Director Peter Faiman Producer John Cornell Screenplay John Cornell, Paul Hogan, Ken Shadie Cinematographer Russell Boyd Editor David Stiven Production Designer Lawrence Eastwood Costume Designer Norma Moriceau Music Peter Best

MAIN CAST

Michael J ‘Crocodile’ Dundee Paul Hogan Sue Charlton Linda Kozlowski Walter Reilly John Meillon Neville Bell David Gulpilil Richard Mason Mark Blum Sam Charlton Michael Lombard Gus Reginald VelJohnson Donk Steve Rackman Nugget Gerry Skilton Danny Rik Colitti Irving Irving Metzman Karla Nancy Mette Simone Caitlin Clarke Gwendoline Anne Carlisle

Endnotes

| 1 | Jeanette Hoorn, ‘White Lubra/White Savage: Pituri and Colonialist Fantasy in Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised (1936)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, 2005, pp. 48–63. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For a discussion of the impact of 10BA on the form taken by Crocodile Dundee,see Meaghan Morris, ‘Tooth and Claw: Tales of Survival and Crocodile Dundee’, Social Text, no. 21, 1989, pp. 105–27. |

| 3 | Stephen Crofts, ‘Cross-cultural Reception Studies: Culturally Variant Readings of Crocodile Dundee’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 1992, p. 221. |

| 4 | Siegfried Kracauer, Nature of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, Dennis Dobson, Oxford, 1960, p. 282. |

| 5 | Margaret Maynard, Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, p. 173. |

| 6 | ibid. |

| 7 | Catherine Hakim, Honey Money: The Power of Erotic Capital, Allen Lane, London, 2011. |

| 8 | Nicholas Chare, Sportswomen in Cinema: Film and the Frailty Myth, I.B. Tauris, London & New York, 2015, pp. 121–2. |

| 9 | Anna Edmundson & Chris Boylan, Adorned: Traditional Jewellery and Body Decoration from Australia and the Pacific, Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1999, p. 10. |

| 10 | Recognising the importance held by ale in many an Australian male psyche, Bob Hawke, the prime minister of Australia at the time Crocodile Dundee was released, used to make much of his beer-drinking prowess, regarding it as an election asset. The enduring importance of this aptitude in some quarters of Australia is demonstrated by the wide reportage of Hawke’s ability to scull a beer at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 2012. |

| 11 | For a discussion of hardness as a masculine attribute, see Nicholas Chare, ‘Getting Hard’, in Adam Locks & Niall Richardson (eds), Critical Readings in Bodybuilding, Routledge, New York, 2012, pp. 199–214. |

| 12 | For an analysis of many of the differences between these two releases, see Stephen Crofts, ‘Re-imaging Australia: Crocodile Dundee Overseas’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 1989, pp. 129–42. |

| 13 | Ruth Abbey & Jo Crawford, ‘Crocodile Dundee? Or Davy Crockett?’, Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 23, no. 4, 1990, p. 159. |

| 14 | Morris, op. cit., p. 117. |

| 15 | Morris recognises this source; see ibid., p. 120. |

| 16 | Garry Gillard, ‘Like a Tarzan Comic: Crocodile Dundee’, Screen Education, no. 44, 2006, p. 128. |

| 17 | Yvonne Tasker, Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and Action Cinema, Routledge, London, 1993, p. 50. |

| 18 | Marianna Torgovnick, Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990, pp. 64–5. |

| 19 | bell hooks, ‘Feminism Inside: Toward a Black Body Politic’, in T Golden (ed.), Black Male, Abrams, New York, 1994, p. 131. |

| 20 | Tasker, op. cit., p. 50. |

| 21 | Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire, trans. Harry Zohn, Verso, London, 1997, p. 132. |

| 22 | Abbey & Crawford, op. cit., p. 162. |

| 23 | For an examination of the role of the pastoral in the Australian imaginary, see Jeanette Hoorn, Australian Pastoral: The Making of a White Landscape, Fremantle Press, Fremantle, 2007. |

| 24 | Abbey & Crawford, op. cit., p. 162. |

| 25 | Veronica Brady, ‘Evading History’, Australian Society: A Magazine of Social Issues, vol. 7, no. 3, 1987, p. 34. |

| 26 | This phenomenon is recognised by Neil Rattigan, who regards it as an attempt to aestheticise the outback; see Rattigan, ‘Apotheosis of the Ocker’, Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 15, no. 4, 1988, p. 150. |

| 27 | Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone, New York, 1995, p. 29. |

| 28 | TJ Clark, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing, Yale, New Haven, 2006, p. 123. |

| 29 | Nichola Tooke & Michael Baker, ‘Seeing Is Believing: The Effect of Film on Visitor Numbers to Screened Locations’, Tourism Management, vol. 17, no. 2, 1996, p. 89. |

| 30 | Morris, op. cit., p. 112. |

| 31 | I wish to thank Nick Chare – who shares with me a long-term affection for Crocodile Dundee – for the many insights that he has given to me and that appear in this article. I also wish to express my gratitude to Nick for his outstanding contribution to teaching and research in film studies, gender studies and art history at the University of Melbourne. |