THE NFSA RESTORES COLLECTION: PART 60

The genesis for Louis Nowra’s 1993 play Radiance was, in the playwright’s own words, ‘the sight of an unknown woman walking across the nocturnal mud flats, as they glistened in the moonlight’.[1]Louis Nowra, ‘Women on the Mud Flats’, in Nowra, Radiance: The Play + The Screenplay, Currency Press, Sydney, 2000, p. vii. This image, which Nowra observed in the late 1980s when viewing the mudflats that stretched from Kinka Beach in Queensland towards Great Keppel Island, would coalesce a number of years later with a friend’s tale of caring for her dying mother and the ‘strange and awkward family reunion’ of the friend with her four siblings, all of whom had different fathers, at their mother’s funeral.[2]ibid. Bringing together this memory and his friend’s story in May 1992, Nowra recalls being ‘seized by the image of three Aboriginal half-sisters standing on the glistening mudflats staring towards what would become Nora Island’.[3]ibid. Although Rachel Perkins, the Arrernte and Kalkadoon filmmaker who emotively transposed Nowra’s play to the silver screen, did not see any of the various theatrical productions of Radiance, she was exposed to the text by her friend Trisha Morton-Thomas, who performed a monologue from the play as part of her end-of-year performance.[4]Catherine Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins: Director of Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, p. 32. After approaching Nowra with a proposal to adapt Radiance as a thirty-minute short, Perkins would instead take up his suggestion that she expand it into a feature, and worked with Nowra on its cinematic translation.

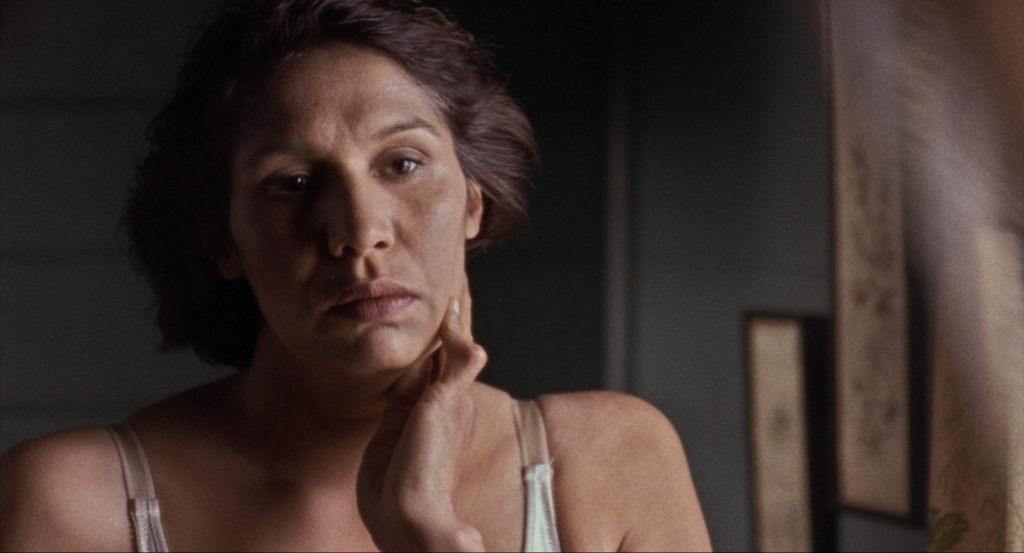

Inducting a number of firsts in the director’s career, as well as within the broader Australian film industry, Radiance (1998) was described by Perkins as ‘the first Aboriginal film to have jokes in it’,[5]Rachel Perkins, cited in Ceridwen Spark, ‘Reading Radiance: The Politics of a Good Story’, Australian Screen Education, no. 32, Spring 2003, p. 100. and was touted in the press as ‘the first commercial film in Australia to be directed by an Aboriginal woman’.[6]Mike Houlahan, ‘Kiwi Film Shines Light for Aussie’, The Evening Post, 20 July 1998, p. 11. ‘Commercial’ is the keyword here; beDevil (1993), directed by Indigenous filmmaker Tracey Moffatt, preceded Radiance by five years but only had a limited theatrical release. For more on this film and Moffatt’s work, see Virginia Fraser, ‘beDevilling’, Metro, no. 96, Summer 1993/1994, pp. 15–8, available at <https://metromagazine.com.au/bedevilling/>, accessed 31 January 2024. Hewing closely to Nowra’s play, the film captures the reunion of three half-sisters as they return to their childhood home in Queensland for their mother’s funeral. The eldest sister, Cressy (Rachael Maza), has cast aside her origins to become a renowned opera singer based overseas; the middle sister, Mae (Morton-Thomas), is a nurse who has bitterly remained with their mother to fulfil the unenviable job of caring for her as she slides further into precocious senility; and the youngest sister, Nona (Deborah Mailman), is a naive romantic who drifts between whimsical ideas, places, jobs and lovers. The sisterly reunion, which takes place over the course of twenty-four hours, lays bare a number of old wounds from their childhood, as the sisters – who all have different fathers and possess conflicting memories of their childhood as well as varying degrees of resentment towards their mother – both individually and collectively deal with their grief.

As the film progresses, the site of grief transitions from the death of their mother to the fractured bonds between the sisters, which started with Cressy and Mae being taken away by the authorities as young girls and placed in state care. Although Nona stayed with their mother as a girl and possesses the most tender childhood memories of her, she is also the sister who is most strongly impacted by their gathering. Exposing her sense of self as pure fantasy, the film climaxes with the revelation that Cressy is actually Nona’s mother. Nona also learns that the person she thinks is her father – a man on the rodeo circuit known as the ‘Black Prince’ – is a complete fabrication, and that her real father was a boyfriend of their mother who raped Cressy under the house when she was twelve years old. In what is arguably a double trauma, having only recently discovered that she is pregnant, Nona’s dream of raising her own baby in their childhood home is destroyed when Mae reveals that the house, which is owned by their mother’s ex-lover Harry Wells, is being repossessed. While Nona is the only sister interested in recapturing and preserving the nostalgia of their childhood home, Cressy and Mae are determined to exorcise the painful mnemonic debris built into the house’s foundations and to take revenge on the fickle Harry by burning the house to the ground.

As in Nowra’s play, their mother’s home – a ramshackle Queenslander sitting at the top of a cliff overlooking the beach, with the fictional Nora Island in the distance – is the central space of the film. Not merely functioning as a site of reunion, it is haunted with memories of the sisters’ childhood and uncanny echoes of their mother, which are manifest in the objects, furniture and nooks and crannies of the house’s decaying architecture. To authentically re-create the play’s strong sense of place, filming for Radiance occurred across six weeks, with half the time spent in a studio and the other half on location in the small Queensland coastal town of Seventeen Seventy, which takes its name from the year in which James Cook arrived there on his second landing on Australian soil, and Hervey Bay.[7]Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins’, op. cit., p. 32. In a twist of verisimilitude, Cressy and Mae’s burning of the house in the penultimate scene of the film was not a simulation, as the house’s owner gave permission for it to be set alight for the film in exchange for ‘a thousand dollars and a crate of Moet’.[8]Rachel Perkins, quoted in Simpson, ibid., p. 33.

Although Radiance establishes its identity as an Australian film through its location, being situated between the sugarcane fields and the Queensland coast, the critical response to the film as a narrative dealing with Indigenous issues was handled rather ambiguously upon its release. A number of critics chose to view the film through a broad lens as universally Australian, effectively denying the cultural and racial specificity of the film’s characters, with one reviewer describing their status as First Nations people as ‘incidental’.[9]Evan Williams, ‘A Warm Inner Glow’, The Weekend Australian Review, 10 October 1998, p. 21. Notwithstanding this viewpoint, which will be discussed in further detail throughout this essay, Perkins’ sensitive engagement with the themes of identity formation, belonging, dispossession and the stolen generations is undoubtedly the start of a sustained filmic practice in which she has worked to demarginalise narratives centring on First Nations peoples. To this end, a number of scholars, including cinema studies researcher Felicity Collins, have convincingly positioned Perkins’ oeuvre within the ‘Blak Wave’ – a term coined to define ‘a slow revolution [that] has taken place in Australia’s publicly funded screen culture’, which has been ‘enabled by policy initiatives since the 1980s to support Indigenous production’ and ‘was seeded in the context of a symbolic reconciliation movement that, in the lead-up to the 2001 centenary of Federation, performed a new relationship between Indigenous and settler Australia’.[10]Felicity Collins, ‘Disturbing the Peace: The Ghost in beDevil and The Darkside’, Critical Arts, vol. 31, no. 5, 2017, p. 108.

Extending the intersection of Perkins’ work with the Blak Wave, Odette Kelada and Maddee Clark contend that her films ‘exemplify both a decolonising poetics and central positioning of Indigenous women’s stories that shift the dominant norm of white, patriarchal narratives’.[11]Odette Kelada & Maddee Clark, ‘Beyond the Wonderland of Whiteness: The Blak Wave of Indigenous Women Shaping Race on Screen’, in Felicity Collins, Jane Landman & Susan Bye (eds), A Companion to Australian Cinema, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2019, p. 108. They further elucidate that Perkins’ cinema ‘embodies a reparative approach […] focusing on opening possibilities and ambiguities rather than foreclosing complexity or assuming inevitability as inherent to oppressive structures’.[12]ibid., pp. 108–9. Indeed, the director’s significant contribution to the representation of contemporary Indigenous narratives has spanned cinematic fictions (One Night the Moon (2001), Bran Nue Dae (2009), Mabo (2012) and Jasper Jones (2017)), narrative television series (Redfern Now, Mystery Road and Total Control) and documentaries (Black Panther Woman (2014), First Australians and The Australian Wars). What is notable about Perkins’ body of work is that it has navigated difficult political topics while possessing a broad commercial appeal – a mode of engagement that arguably began with Radiance’s successful capturing of the public imagination in 1998.

To this end, Radiance won the most popular film award as voted by the audiences at the Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra film festivals,[13]Anne Crawford, ‘Arrernte Auteur’, The Age, 10 October 1998, p. 6. and went on to receive six nominations at the 1998 Australian Film Institute Awards, with Mailman winning the award for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role. Although Radiance’s widespread popularity could be attributed to it having been originally written by Nowra – a white, male playwright – Perkins’ adaptation and the directorial vision she brings as an Arrernte and Kalkadoon woman position the film as a foundational cinematic narrative concerned with delivering ‘layered and complex Aboriginal perspectives to the screen’.[14]Kelada & Clark, op. cit., p. 118. A watershed in 1990s Australian cinema history, Radiance brings a distinctly Indigenous and feminine filmic voice to elucidate urgent issues of identity, belonging and mourning.

‘Up in flames’

Unfolding within an all-enveloping darkness, the cinematic space of Radiance is first heard rather than seen. As the opening credits transition on the screen, Perkins sonically locates the viewer through the soft crashing of waves, the swoosh of wind and the chirping of crickets before the black is dimly illuminated by the flame of a match held between Mae’s fingers. The camera frames her in a tight close-up as she addresses an unseen spectre, ‘You’re still there, aren’t you? Ghosts burn, do you know that?’ She throws the match away and it tumbles across the screen; the film then cuts to Nona running down an urban street before returning to Mae, holding another lit match: ‘He did the dirty on you. Did the dirty on us both.’ Transitioning the action back to Nona, the camera zooms in on her as she sits in a public toilet holding a positive pregnancy test and then transitions to her calling Mae from a public telephone. The exuberance with which she tells Mae that she is ‘coming home’ is immediately undercut when she discovers that their mother has died. Abandoning a shocked Nona, the camera takes in a shadowy domestic interior that is brightened by beams of light escaping through the cracks of the louvre windows. As the light moves across the space, it reveals two Indigenous masks mounted on the wall and a framed black-and-white photograph perched on a desk featuring a beautiful young woman. Lighting a third march, the camera returns to Mae, who continues, ‘But he’ll be too late, and it will all go up in flames.’

Although Perkins has criticised the first ten minutes of Radiance for being ‘a bit slow’,[15]Rachel Perkins, quoted in Gerry Turcotte, ‘“Let the Turtle Live!”: A Discussion on Adapting Radiance for the Screen by Louis Nowra and Rachel Perkins’, Metro, no. 135, January 2002, p. 40. these opening moments are crucial to establishing a number of the film’s key concerns and thematic interests, specifically relating to familial alienation and belonging. At the beginning, the disorienting intercutting between Mae and Nona highlights the intense feeling of estrangement that exists between all three sisters well before their reluctant reunion for their mother’s funeral. Cressy, who is the most distanced from the family unit, is notably the last sister to arrive at their childhood home, and is greeted with tentative tenderness by Nona and apparent indifference by Mae, leading her to announce, ‘I’m not a ghost.’

Visually emphasising Cressy’s comment that the sisters are ‘strangers because of her [their mother]’, cinematographer Warwick Thornton avoids capturing the sisters within a single frame until they attend their mother’s funeral. In this scene, they are forced to collectively inhabit a shot after Mae realises that Father Doyle (Russell Kiefel) has lost track of his sermon while staring at Nona, who is sitting between her two elder sisters on the first church pew with her legs wide open and not wearing any underwear. The delay in the camera settling on this somewhat perverse family portrait also re-enacts the sisters’ apparent lack of belonging within the film’s settings, from the church where Cressy informs Father Doyle that she doesn’t ‘do hymns’, to the local pub where they go to buy alcohol and are met with stares from the other (white, male) patrons, to their childhood home, which is built on conflicting memories that gradually fracture the sisters’ already thin veneer of family togetherness. Indeed, the play on darkness and shadows in the film’s opening sequence – first with the limited illumination provided by the match flames lit by Mae, and then with the rippling light cast on the walls of the house – emphasises the importance of looking deeper.

Lifting the veil

One of the first revelations in the film occurs after Nona announces that she is going to be like their mother ‘and never get married’, to which Mae responds, ‘You didn’t know much about Mum, then. She was desperate to get married.’ After Mae leaves the room, Cressy and Nona’s exchange of divergent memories of their mother results in increased tension. While Nona recalls that their mother was ‘kind’ to her, Cressy struggles with the belief that their mother had them ‘with no concern for [their] future’. Their conversation reveals that both Cressy and Mae, as children, were taken by the authorities and effectively cut off from their mother, who failed to visit them. However, she prevented the same fate befalling Nona by hiding her. When Cressy proclaims, ‘What I can’t forgive is that she didn’t fight for me,’ she is met with painful resistance from Nona:

Well, what could she do? She had no husband. The law was against her. She was young. Forgive her! […] What do you want me to do? Get down on my knees and apologise for the fact that I stayed with her? Mum and I were sluts; what more could you expect? Sluts don’t write; we fuck!

After Cressy slaps Nona across the face and retreats to Mae’s car outside, they eventually reconcile and return to the house, where they are met with the almost ghostly apparition of Mae, romantically lit by candlelight and swaying gently as she stands on the dining room table dressed in a wedding gown. Dramatically lifting the veil off her face, Mae proclaims, ‘It’s Mum’s […] She spent two years paying it off on lay-by at Davis’ haberdashery. It was still in its box under the bed.’ Purchased on the failed promise that she would marry Harry, ‘the man she truly loved’, their mother’s wedding dress is a tactile symbol of the hidden truths that lurk within the crevices of the house. While their mother’s unarticulated desire for the conventions of marriage was kept hidden under the bed, the truth of Nona’s parentage is likewise hidden under the house. Although Mae’s act of lifting the veil initially appears as a cheeky insight into aspects of their mother’s personality that were rarely revealed, it also bears a deeper significance within and outside the diegesis of the film.

The motif of unveiling becomes increasingly important as the film unfolds and the layers of family deception and their troubling links to Australia’s colonial history are revealed. Ironically, when Radiance originally screened in 1998, this aspect of excavating the multiple layers of signification within the film was largely ignored by critics, who praised what they saw as the film’s universality without engaging with the manner in which it deals with contemporary sociocultural issues experienced by First Nations peoples. Surveying a collection of reviews that accompanied the film’s release, Indigenous studies scholar Benjamin Miller argues that

they have stressed either the ‘universal’ aspects of the plot (ignoring the specific racial political issues raised) or the play’s apparent lack of overt Indigenous ‘politics’ (criticizing its de-politicization or ignoring that the de-politicization might itself have political significance). On the one hand, reviewers engage in what might be termed as ‘assimilationist universalizing’ of Aboriginality and, on the other, in what might be termed a ‘segregationist politicizing’ of Aboriginality.[16]Benjamin Miller, ‘Australians in a Vacuum: The Socio-political “Stuff” in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, p. 61. Emphasis in original.

This problematic rendering of the characters’ race as invisible via either assimilation or segregation is evident in the first line of Evan Williams’ review in The Australian (‘What struck me most forcibly […] is that the three Aboriginal women at the centre of things might just as easily have been white’[17]Williams, op. cit.) and the final line of Mark Juddery’s critique in the Canberra Times (‘Incidentally, the sisters are Aborigines. This has some relevance, but is mostly immaterial. These are universal characters, in a universal story’[18]Mark Juddery, ‘Confronting, but Easy to Watch’, The Canberra Times, 10 October 1998, p. 19.). Perhaps not coincidentally, early reviews of Nowra’s play, according to theatre studies scholar Rebecca Pelan, also ‘generally failed to acknowledge any of its Aboriginal content’.[19]Rebecca Pelan, ‘Identity Performance in Northern Ireland and Australia: The Belle of the Belfast City and Radiance’, Australasian Drama Studies, no. 46, April 1995, p. 77. Notwithstanding that Australia also has white stolen generations – children who were forcibly removed from their white, unmarried mothers through illegal adoption practices[20]See Liz Hannan, ‘White Mothers of Stolen Children Also Deserve an Apology’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 2010, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/white-mothers-of-stolen-children-also-deserve-an-apology-20101207-18o7t.html>, accessed 31 January 2024. – the universalising and erasing approach of these reviews with respect to the characters’ Indigenousness has the unfortunate effect of undermining and ignoring the film’s cultural specificity.

Now that more than twenty years have passed since the film’s release, the reviews can be seen as less of a reflection of Radiance than a mirror of a pervasive white anxiety that rippled through some sectors of the country in the aftermath of the 1992 Mabo judgement. Film scholars Felicity Collins and Therese Davis convincingly link that ruling, which in their words confirmed ‘that terra nullius was achieved at the cost of dispossession of Indigenous people from their land, language and culture after 40 000 years of continuous possession’, to the dismantling of the entrenched idea of home in Australia ‘as the place of belonging of white settlers’.[21]Felicity Collins & Therese Davis, Australian Cinema After Mabo, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2004, p. 112. The year following the handing down of the Mabo decision, which coincided with Radiance’s theatrical premiere at Sydney’s Belvoir St Theatre, showed some promise for the furthering of Indigenous rights and recognition with the Federal Parliament’s passing of the Native Title Act 1993, in a year proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly as the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People.

In Australia, then–prime minister Paul Keating inaugurated the event in Australia with a speech in Redfern, urging that the Mabo decision signal ‘an historic turning point, the basis of a new relationship between indigenous and non-Aboriginal Australians’.[22]Paul Keating, ‘Speech by the Hon Prime Minister, P J Keating MP’, Australian Launch of the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People, 10 December 1992, available at <https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/original/00008765.pdf>, accessed 31 January 2024. This hope, however, had not come to fruition by the time of Radiance’s cinematic release. Rather, 1998was a year in which, a mere fifteen months after its establishment, the ultranationalist political party Pauline Hanson’s One Nation gained 22.7 per cent of the primary vote in the Queensland state election.[23]See Chris Salisbury, ‘Twenty Years On, One Nation Is Still Chaotic, Controversial and Influential’, The Conversation, 8 June 2018, <https://theconversation.com/twenty-years-on-one-nation-is-still-chaotic-controversial-and-influential-97247>, accessed 31 January 2024. This fact would appear inconsequential had One Nation not garnered much of their support through an anti-multiculturalist stance that paid implicit homage to the White Australia policy of the early 1900s, and – as researcher Simon Burgess puts it – displayed an ‘impoverished sense of what it is to be Australian’, offering no attempt ‘to engage proactively and productively with Indigenous […] community leaders’.[24]Simon Burgess, ‘One Nation and Indigenous Reconciliation’, in Bligh Grant, Tod Moore & Tony Lynch (eds), The Rise of Right-populism: Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and Australian Politics, Springer, Singapore, 2018, p. 146.

The same year also saw the inauguration of the annual National Sorry Day. Marking the first anniversary of the 26 May 1997 tabling of the Bringing Them Home report, which inquired into the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families,[25]Australian Human Rights Commission, Bringing Them Home, 1997, <https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/pdf/social_justice/bringing_them_home_report.pdf>, accessed 31 January 2024. this significant cultural event notably took place without an official government apology to members of the stolen generations. Rather, then–prime minister John Howard deemed that a formal apology would not be ‘appropriate’,[26]John Howard, quoted in Janine McDonald, ‘Thousands Say Sorry, but Not PM’, The Age, 27 May 1998, available at <https://www.theage.com.au/national/from-the-archives-1998-thousands-say-sorry-but-not-pm-20210521-p57tyr.html>, accessed 31 January 2024. a far cry from the positive reconciliation intimated in Keating’s 1992 speech. Radiance was thus released at a time when the politics around Indigenous identity were deeply divisive and the dominant political consciousness was unassailably white. From this perspective, film critics’ readings of Radiance as a universal story that aligns equally with Indigenous and white Australian experience enacts what Belinda Smaill refers to as ‘the conspicuous and uneasy staging of white hegemony in Australia’s past’.[27]Belinda Smaill, ‘Asianness and Aboriginality in Australian Cinema’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 30, no. 1, 2013, p. 89. This is not to suggest that it was Perkins’ intention to erase her characters’ Indigenousness, but rather that the film was received through a cultural filter in which whiteness was not merely privileged, but excessively dominant over signs of perceived otherness.

‘We should claim it’

Although knowledge of this historical axis is not necessary for a viewing of Radiance, I contend that an understanding of the sociopolitical events surrounding its release not only enriches a more nuanced reading of the film, but also assists with disentangling its reductive critical reception that actively worked against seeing the sisters as First Nations characters. Significantly, the sisters’ unspoken Indigenousness in the film pays respect to the wishes of Maza, Lydia Miller and Rhonda Roberts, the three actresses who appeared in the first run of Nowra’s play at Belvoir St Theatre. As Nowra recalls, ‘During rehearsals [Maza, Miller and Roberts] determined that Radiance should not be seen as “an Aboriginal play”. In other words, they didn’t want an issue-based play where the Aboriginal characters became abstractions in order to make polemical points.’[28]Nowra, op. cit., p. ix. The decision to infer rather than openly state the sisters’ Indigenousness in the film can also be traced to a perceptive comment made by Perkins during a 1998 interview:

I suppose particularly because it’s indigenous, we wanted to go out to the broadest audience possible. There’s a perception that Aboriginal film is inaccessible because it’s Aboriginal and it’s boring and it’s too hard, and we deliberately approached Radiance not to make it … not so much commercial, but more accessible I suppose.[29]Perkins, quoted in Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins’, op. cit., p. 33.

Importantly, Perkins’ comment does not imply that the characters should be identified as universal (in other words, as white) or that she has willingly sought to render the sisters’ collective background opaque. Rather, it suggests that the film’s identity politics are sensitive to the pre-Apology period in which Radiance was released. This line of thought was supported by Mailman, who commented that, while the film is ‘about three Aboriginal women’, ‘it doesn’t treat them like a social problem’.[30]Deborah Mailman, quoted in Ruth Hessey, ‘Ray of Light’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October 1998, p. 9. In this sense, the focus on the intimate and personal relationships between the sisters allows a subtle enlargement of the film’s sociopolitical themes without placing the audience in the position, in Morton-Thomas’ words, of being ‘preached to about Aboriginal issues’.[31]Trisha Morton-Thomas, quoted in Hessey, ibid. Communication studies theorist Theodore F Sheckels interprets the film’s indirect acknowledgement of race as a subversive ‘strategy’:

One can only imagine how Perkins’s effort would have been received if the political message in the film had been overt, not indirect. Second, the indirection allows the controversial, uncomfortable message to sink gradually into the minds and consciences of white viewers. A frontal assault is, as military and rhetorical strategists both know, often ineffective. Not only is there a potential backlash but there is the strong likelihood of rejection.[32]Theodore F Sheckels, ‘The “Stolen Generations” in Feature Film: The Approach of Aboriginal Director Rachel Perkins and Others’, in Belinda Wheeler (ed.), A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature, Camden House, Rochester, NY, 2013, p. 180.

The effect is that, much like the figure of their mother, the issue of the sisters’ race never fully manifests and is left to haunt the periphery of the narrative. Although Ceridwen Spark contends that ‘Radiance’s refusal to engage directly or explicitly with interracial politics has some unfortunate consequences’[33]Ceridwen Spark, ‘Gender and Radiance’, Hecate, vol. 27, no. 2, January 2001, p. 42. that lead to the reinscription of ‘white denial and indifference’,[34]ibid., p. 47. a quality that, in Nowra’s formulation, is ‘in the nervous system […] the musculature, the habitus of the [Australian social] body’,[35]Louis Nowra, cited in Spark, ibid. I would argue that the indirect expression of racial issues within the film is an apt metaphor for the status of Indigenous rights and acknowledgement in the 1990s. However, Perkins does not simply replicate the repressed status of Indigenous rights in the public arena at the time. Instead, through Radiance, she reclaims First Nations narratives via the subtle embedding of her Indigenous agenda within the textures of the film. In this sense, these textures – which include Cressy’s articulation of her and Mae’s experience of being taken from their mother as children, Nona’s desire to fulfil the Indigenous ritual of killing and eating a turtle and the references to their ancestors’ dispossession of Nora Island, which Nona jokingly suggests they ‘should claim’ from the Japanese developers who have transformed the island into a luxury resort destination – function like the wedding gown under their mother’s bed: they do not merely exist in isolation, but gesture towards unspoken memories and historical markers.

Radiant memories

In confronting the unresolved and buried fragments of the past, the true power of Radiance resides within the film’s clever balancing of moments of extreme grief and humour. This is particularly the case in the scene in which Nona decides to transfer their mother’s ashes into a glass vase so that their mother will look ‘classy’ when she takes her ashes over to Nora Island to be scattered. Confronted with the reality of tipping the ashes into the vase, however, Nona freezes, and she and Mae proceed to fight over the contents of the box, eventually spilling the ashes on the floor and all over Cressy – who comments, ‘I’m going to have to tell the laundry, “That’s not a stain; that’s my Mum,”’ causing herself and her sisters to burst out laughing. After Mae vacuums the spilt remains off the carpet and dumps the contents of the vacuum bag onto a plate so that the sisters can filter out the balls of dust and other detritus that have now been mixed with the ashes, Nona comes up with the idea of placing the ashes in an empty liquorice nougat tin:

NONA: I’ve got it: the tin box – Radiance Liquorice Nougat. [Nona pronounces ‘nougat’ with a hard t sound at the end.]

CRESSY: Nougat. [Cressy corrects Nona’s pronunciation.]

NONA: No, that Italian fellow bought it for Mum. Even when it was empty, it still smelt delicious.

MAE: You’re not going to put Mum in a tin box.

NONA: She’ll smell great.

MAE: Where are you going?

NONA: Under the house.

CRESSY: No, don’t go under the house.

NONA: Anyone want to join me?

[Nona leaves the kitchen.]

CRESSY: Nona!

As a word that is etymologically imbued with paradox, ‘radiance’ evokes both the beauty of a glowing complexion and the potential danger of increased exposure to reflected light or heat. In this sense, it serves as an apt metaphor for the film’s tension between light and shadows, memory and reality, and humour and grief.

On a surface level, the ‘radiance’ that the film’s title alludes to is the brand name printed on the liquorice nougat tin that Nona imbues with childhood nostalgia. As a deeply symbolic object, the tin is a tactile receptacle for Nona’s desire to reconstruct her memories of the time when the family unit was intact. During the scene in which the sisters return home following the funeral, Nona reminisces about how their gathering replicates the last time they were together when she was a young girl: ‘This is like last time […] The three of us. You were passing through to go to that music conservatorium in London. I was five. We had a picnic, down on the beach there. Mum. Us.’ In Nona’s desperation to recapture the sisters’ previous reunion, she ensures that Cressy misses her flight to Sydney and that they have to return to their mother’s house. Later, when she follows Cressy outside to the beach and spots a turtle on the shore, the turtle also plays a part in her sentimental plot as she and Cressy take it back home with them. When Mae asks, ‘Why don’t you just let the little bugger go?’, Nona replies, ‘Don’t be slack! It’ll be like last time, remember? Curried turtle, mum here – well, her ashes, anyway – you, me, Cressy. Let’s have a proper wake for her. We’ll do it right, traditional way.’ However, when Nona realises that she doesn’t possess the resolve to kill the turtle, she suggests they have spaghetti instead and asks for candles. Although Mae humorously interprets the request for candles as enabling Nona to wax the turtle’s ‘bikini line’, Nona’s response makes her intentions clear: ‘Remember last time we had dinner by candlelight?’

Despite Nona’s best intentions, the fallibility of memory becomes increasingly evident after she fetches the tin of liquorice nougat from under the house, unaware that it is the site of Cressy’s adolescent trauma, and the latter is forced by Mae to tell the truth about Nona’s conception. However, Cressy initially claims that, while she was playing under the house, she heard their mother being raped. Refusing to believe Cressy’s story, Nona opens the tin, only to discover that it has ‘lost the smell of liquorice’. As an allusion to the film’s problematisation of nostalgia, the scentless, empty tin also ties back to the film’s thematic concern with looking deeper and not being seduced or deceived by what appears on the surface. As film historian Anthony Adah writes,

Narrative progression is organized around the revelations that highlight the destructive power of repressed Aboriginal personal and collective histories. At a broader level, the repressed family histories parallel the repressed histories of the nation and draw attention to their traumatic and psycho-social effect.[36]Anthony Adah, ‘Agential Mortality: Death, Corporeality, and Identity in Radiance (1997)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, Winter–Spring/Summer 2005, p. 37.

By engaging with painful and buried family memories and, by extension, larger collective histories, Radiance cleverly draws on the architecture of the mother’s house as a visual representation of the conflict between past repressions and present revelations. Taking the form of a traditional Queenslander that is raised on stilts and fronted by a verandah partially concealed by filigree screens, the elevated, main part of the house stands in contrast with the murky realm that lies beneath. Catherine Simpson – drawing on the work of novelist David Malouf, who broadly characterises such a space as ‘an unstructured void’[37]David Malouf, cited in Catherine Simpson, ‘Notes on the Significance of Home & the Past in Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, p. 30, available at <https://metromagazine.com.au/notes-on-the-significance-of-home-the-past-in-radiance/>, accessed 31 January 2024. – writes that, in Radiance, the area under the house is ‘endowed with both menacing and subliminal significance’.[38]Simpson, ibid. Indeed, when this void first appears in the film after Nona goes in search of the liquorice nougat tin, its shadowy depths are visually contrasted with the warmth of the house, which is bathed in the glow of candlelight. Not yet knowing the truth about Cressy’s violation and still viewing this space as a site of play, Nona calls out, ‘Here comes the bogeyman,’ and then accidentally knocks over and smashes a mirror. A portent of bad luck, the smashed mirror acts as the symbolic splintering of Nona’s idealised vision of her family. Further, her play-acting as ‘the bogeyman’ sets in motion the disclosure of the real layers of psychological disturbance that dwell within the space of the home, which can only be vanquished when it is set alight in what Cressy describes as ‘operatic’ fashion.

Signs of love, sites of haunting

Prefiguring the eventual burning of the house, the first long shot that takes in the Queenslander’s exterior, surrounded by tropical palm trees and overlooking the beach, is symbolically juxtaposed with an image of a large plume of smoke arising from the cane fields. The motif of fire is reinforced by the wisps of smoke rising to the right of the house, where it is revealed that Mae is burning their mother’s possessions, much to Nona’s distress. Far from the tropical paradise that the location initially suggests, both Perkins and Nowra have spoken about how the cinematic portrayal of the family home is indebted to the Gothic tradition, with Nowra specifically commenting that the void under the house is ‘where the monster is, which is the residue of the mother’.[39]Louis Nowra, quoted in Turcotte, op. cit., p. 39.

The transposition of the haunting and claustrophobic characteristics of the Gothic genre to an Australian national film context to explore what Anne Barnes describes as ‘issues surrounding colonisation, race, gender, and identity’[40]Anne Barnes, ‘Mapping the Landscape with Sound: Tracking the Soundscape from Australian Colonial Gothic Literature to Australian Cinema and Australian Transcultural Cinema’, Critical Arts, vol. 31, no. 5, 2017, p. 159. finds particular expression in Radiance, with the house functioning as a site of multiple hauntings and dispossession. In the words of humanities scholar Sue Gillett, ‘The family home that is a traumatic site for Cressy, a nostalgic retreat for Nona and a mausoleum for Mae, does not, and never did, belong to them.’[41]Sue Gillett, ‘Through Song to Belonging: Music Finds Its Place in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance and One Night the Moon’, Metro, no. 159, 2008, p. 89. Crucially, the sisters’ individual and largely irreconcilable feelings towards the house stem from their respective relationships with their mother. While Nona believes that it was gifted to their mother by Harry as ‘a sign of his love’, thereby continuing her unrealistic view of both her mother as a true maternal figure and her infidelity as a romance, Cressy tells the truth and says that the house was a bribe by Harry to prevent their mother from telling his wife about their affair. Meanwhile, Mae has the most caustic characterisation of their mother, telling Cressy,

She was a witch. She was. She spat on people if I took her out. Cursed anyone in the street – men, women, children. Spat on them. Why do you think no-one turned up today? No-one goes to [the] funeral service of a witch.

Notably, in Radiance the mother is only featured through the sisters’ memories and the framed black-and-white photograph that the camera appears to compulsively return to throughout the film. In outlining the creative process for cinematically imagining the mother, Perkins has stated that she and Nowra pondered the questions ‘Do we show the mother? Do we have flashbacks to show the past?’ before ultimately deciding ‘that the story was not to do with the past but actually to do with the present and how their lives unfold in the present’.[42]Perkins, quoted in Turcotte, op. cit., p. 36. By eschewing the use of flashbacks and instead representing the mother through the home’s interior spaces and objects – such as her photograph, her clothing and the chair in which she passed away – Perkins emphasises the Gothic trope of the past uncannily impinging on the present.[43]See Andrew Smith, Gothic Literature, 2nd edn, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK, 2013 [2007], p. 14. The photograph achieves this effect in particular: though it is shot as a still life, it also often appears within the mise en scène to further emphasise the mother’s absent presence. For example, during the scene in which Cressy carefully conceals Nona’s bruised eye before going to the funeral, Thornton composes the shot so that the photograph is positioned in the background as a silent witness to what is unfolding.

This visual detail, which does not feature in Nowra’s play, is strikingly accompanied by another image, featuring the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Not just an enduring symbol of their mother’s Catholicism – referred to by the priest during the funeral service – the image of Christ ironically intimates a level of love, compassion and devotion that Cressy and Mae feel was particularly lacking from their mother towards them. Undoubtedly, it also gestures towards the state-sanctioned removal of Cressy and Mae from their home and their subsequent placement in convents, thereby drawing attention to the institutions that have effectively destroyed their sense of family and belonging. When the respective images of their mother and Christ are both doused with petrol as Cressy and Mae prepare to burn down the house, this is presented as the final exorcism of the entrenched institutions of family and church that have either abandoned or diminished them.

However, haunting in the film is not solely focused on the mother; it also encompasses the fictional figure of Madame Butterfly. Before Cressy appears in the film, she is first seen on the cover of a Madame Butterfly CD, while her embodied entrance in the film is accompanied by her own rendition of ‘Che tua madre dovrà’, which Nona plays on their mother’s stereo. As Craven suggests, the importance of Giacomo Puccini’s 1904 opera extends beyond Cressy’s occupation as an opera singer and her ability to transcend the shackles of her past – if only via performance – to function as a key intertextual referent that mirrors elements of her own family history. As Gillett contends, ‘Without conscious acknowledgement of their shared history, Cressy, in the role of Butterfly, has used that voice to lament their common fate as young mothers, wronged by their seducers and robbed of their children.’[44]Gillett, op. cit., p. 89. Significantly, it is Nona and not Cressy who appears in the role of Butterfly in the film. Sung while wearing a vibrant, salmon-pink kimono that she bought after seeing one of Cressy’s performances on television, Nona’s rendition of ‘Un bel dì, vedremo’ transforms the aria’s pathos into comic melodrama. Moreover, her reimagining of Puccini’s lyrics gestures towards her true parentage by mimicking the performative role taken on by her biological mother (Cressy) while, strangely, also giving voice to her grandmother’s romantic experiences: ‘My life is shit. My boyfriend left me for another woman. He’s a big arsehole, and she’s a slut.’ The slippages of identity in this scene foreshadow the numerous performances built into the family’s construction.

‘Just like Mum – she was into dress-ups too’

Although the drama at the heart of Radiance pivots on the revelation that Cressy is Nona’s biological mother, the anxiety of identity is not just confined to the relationship between Cressy and Nona, but is also traumatically articulated by Mae in the scene in which the sisters walk along the mudflats:

Who are you? Who is me? I’d ask her again and again. But she wouldn’t tell me. That thing wouldn’t tell me. And yet, I looked after her. I wanted to know where I came from. I wanted to know why my grandparents got thrown off that island. I wanted to know about my father. About her.

With no recourse to answer these questions, Radiance stages the search for identity and belonging through the mother’s clothing. As a form of somatic memory, the act of dressing up and trying on the identity inherited through clothing first takes place when Nona is getting ready for the funeral and puts on a blue-and-white patterned dress from their mother’s wardrobe. Although she happily admires her reflection in the mirror, she eventually chooses to wear her own dress and wig, and later asks Cressy if she can wear her elegant lilac scarf. Though a small gesture, Nona’s rejection of her mother’s dress is the first indication that she does not have a strong maternal connection with the woman she believes to be her mother. Meanwhile, Nona’s link to Cressy is shown when she copies the latter’s absent-minded action of fiddling with the necklace she’s wearing, as well as her exclamation that she also wants to become a singer before launching into a rendition of ‘My Island Home’.

On the other hand, Cressy and Mae have an entirely different experience when they wear their mother’s clothes and gaze into their mother’s bedroom mirror, first when Mae puts on her mother’s unworn wedding gown, and later when Cressy slips out of her grey suit, which has been soiled with her mother’s ashes, into the blue-and-white dress that Nona originally tried on at the beginning of the film. In both scenes, this process of dressing up and looking at their reflections is, significantly, met with the disembodied voice of their mother singing in the Birri-Gubba language.[45]See ibid. Notably, however, in the scene in which Nona looks into the mirror when wearing the dress, she hears nothing. The fashioning of a cohesive family identity between the sisters and broader sense of agency are only achieved in the film’s final moments, through – surprisingly – Nona’s collection of wigs. Returning after scattering their mother’s ashes on Nora Island, she finds Cressy and Mae surreptitiously waiting for her in the latter’s car, wearing Nona’s wigs to evade detection after the previous night’s arson.

The wearing of the wigs signals a different form of self-determination: one in which the sisters no longer attempt to define their identity as being with their mother, but instead with one another. As Adah argues, the ending reinforces ‘that home or identity is neither to be found in the Queenslander, nor in Nora Island, but in the memories, revelations, and experiences the women share’.[46]Adah, op. cit., p. 44. As the sisters burn the house, destroy the ghosts of the past and start afresh, the film’s soundtrack also signals this transition: as Nona arrives on Nora Island to scatter her grandmother’s ashes, the aural dominance of Puccini’s opera is silenced by Australian folk trio Tiddas’ version of ‘My Island Home’. In yet another reference to the film’s title, the violent flames of the previous night’s fire are replaced with the scattered ashes that float in the air and appear to reflect the sun’s light in gold-flecked splendour. By ending with a song that Gillett argues is ‘a contemporary assertion of possession, identity, restitution and belonging’,[47]Gillett, op. cit., p. 87. Perkins underlines the theme of reconciliation that runs through Radiance. Moreover, while the play concludes with the sisters going their separate ways, the film visually reinstates positive familial bonds by showing the sisters driving towards an unknown future together – even though Nona’s final line is ‘There’s no fucking way I’m calling you “Mum”.’

In a 2014 reflective essay entitled ‘A Rightful Place’, Perkins responds to land rights activist Noel Pearson’s aspiration of achieving ‘constitutional recognition of indigenous Australians’ by bringing together Australia’s ‘ancient heritage’, ‘British heritage’ and ‘multicultural triumph’.[48]Noel Pearson, cited in Rachel Perkins, ‘A Rightful Place’, Quarterly Essay, no. 56, January 2014, p. 82, available at <https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/correspondence/332>, accessed 21 February 2024. In so doing, she touches on the manner in which broad narratives of Australian identity and culture have relied on a covert legacy of racial erasure. Referring specifically to reactions to her documentary series First Australians, which maps Australia’s modern history from the arrival of British colonists in 1788 to the handing down of the Mabo verdict in 1992, she writes, ‘I understood how fundamentally the institutions and the structures of our society have failed to provide our citizens with any understanding and ownership of their deep Australian heritage.’[49]Perkins, ibid., p. 83. Although Radiance does not explicitly put forward the line of activism that has become a signature of Perkins’ oeuvre, it is nonetheless the spark from which her subsequent films have burned. Her debut feature establishes that, in a similar fashion to the layered history of Australia and its First Nations peoples, identity is not fixed but in a constant process of becoming. Ultimately, it shows that it takes only one match to cast a light.

Select bibliography

Anthony Adah, ‘Agential Mortality: Death, Corporeality, and Identity in Radiance (1997)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, Winter–Spring/Summer 2005, pp. 35–47.

Sue Gillett, ‘Through Song to Belonging: Music Finds Its Place in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance and One Night the Moon’, Metro, no. 159, 2008, pp. 86–92.

Ruth Hessey, ‘Ray of Light’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October 1998, p. 9.

Odette Kelada & Maddee Clark, ‘Beyond the Wonderland of Whiteness: The Blak Wave of Indigenous Women Shaping Race on Screen’, in Felicity Collins, Jane Landman & Susan Bye (eds), A Companion to Australian Cinema, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2019, pp. 107–30.

Benjamin Miller, ‘Australians in a Vacuum: The Socio-political “Stuff” in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, pp. 61–71.

Louis Nowra, ‘Women on the Mud Flats’, in Nowra, Radiance: The Play + The Screenplay, Currency Press, Sydney, 2000, pp. vii–xiv.

Rebecca Pelan, ‘Identity Performance in Northern Ireland and Australia: The Belle of the Belfast City and Radiance’, Australasian Drama Studies, no. 46, April 1995, pp. 70–9.

Theodore F Sheckels, ‘The “Stolen Generations” in Feature Film: The Approach of Aboriginal Director Rachel Perkins and Others’, in Belinda Wheeler (ed.), A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature, Camden House, Rochester, NY, 2013, pp. 173–86.

Catherine Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins: Director of Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, pp. 32–4.

Catherine Simpson, ‘Notes on the Significance of Home & the Past in Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, pp. 28–31, available at <https://metromagazine.com.au/notes-on-the-significance-of-home-the-past-in-radiance/>.

Belinda Smaill, ‘Asianness and Aboriginality in Australian Cinema’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 30, no. 1, 2013, pp. 89–102.

Ceridwen Spark, ‘Gender and Radiance’, Hecate, vol. 27, no. 2, January 2001, pp. 38–49.

Ceridwen Spark, ‘Reading Radiance: The Politics of a Good Story’, Australian Screen Education, no. 32, Spring 2003, pp. 100–4.

Gerry Turcotte, ‘“Let the Turtle Live!”: A Discussion on Adapting Radiance for the Screen by Louis Nowra and Rachel Perkins’, Metro, no. 135, January 2002, pp. 34–40.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1998 Length 83 minutes Production Company Eclipse Films Producers Ned Lander, Andrew Myer Director Rachel Perkins Screenplay Louis Nowra Director of Photography Warwick Thornton Editor James Bradley Production Designer Sarah Stollman Costume Designer Tess Schofield Music Alistair Jones

MAIN CAST

Nona Deborah Mailman Mae Trisha Morton-Thomas Cressy Rachael Maza Father Doyle Russell Kiefel The Barman Ben Oxenbould

Endnotes

| 1 | Louis Nowra, ‘Women on the Mud Flats’, in Nowra, Radiance: The Play + The Screenplay, Currency Press, Sydney, 2000, p. vii. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | Catherine Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins: Director of Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, p. 32. |

| 5 | Rachel Perkins, cited in Ceridwen Spark, ‘Reading Radiance: The Politics of a Good Story’, Australian Screen Education, no. 32, Spring 2003, p. 100. |

| 6 | Mike Houlahan, ‘Kiwi Film Shines Light for Aussie’, The Evening Post, 20 July 1998, p. 11. ‘Commercial’ is the keyword here; beDevil (1993), directed by Indigenous filmmaker Tracey Moffatt, preceded Radiance by five years but only had a limited theatrical release. For more on this film and Moffatt’s work, see Virginia Fraser, ‘beDevilling’, Metro, no. 96, Summer 1993/1994, pp. 15–8, available at <https://metromagazine.com.au/bedevilling/>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 7 | Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins’, op. cit., p. 32. |

| 8 | Rachel Perkins, quoted in Simpson, ibid., p. 33. |

| 9 | Evan Williams, ‘A Warm Inner Glow’, The Weekend Australian Review, 10 October 1998, p. 21. |

| 10 | Felicity Collins, ‘Disturbing the Peace: The Ghost in beDevil and The Darkside’, Critical Arts, vol. 31, no. 5, 2017, p. 108. |

| 11 | Odette Kelada & Maddee Clark, ‘Beyond the Wonderland of Whiteness: The Blak Wave of Indigenous Women Shaping Race on Screen’, in Felicity Collins, Jane Landman & Susan Bye (eds), A Companion to Australian Cinema, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2019, p. 108. |

| 12 | ibid., pp. 108–9. |

| 13 | Anne Crawford, ‘Arrernte Auteur’, The Age, 10 October 1998, p. 6. |

| 14 | Kelada & Clark, op. cit., p. 118. |

| 15 | Rachel Perkins, quoted in Gerry Turcotte, ‘“Let the Turtle Live!”: A Discussion on Adapting Radiance for the Screen by Louis Nowra and Rachel Perkins’, Metro, no. 135, January 2002, p. 40. |

| 16 | Benjamin Miller, ‘Australians in a Vacuum: The Socio-political “Stuff” in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, p. 61. Emphasis in original. |

| 17 | Williams, op. cit. |

| 18 | Mark Juddery, ‘Confronting, but Easy to Watch’, The Canberra Times, 10 October 1998, p. 19. |

| 19 | Rebecca Pelan, ‘Identity Performance in Northern Ireland and Australia: The Belle of the Belfast City and Radiance’, Australasian Drama Studies, no. 46, April 1995, p. 77. |

| 20 | See Liz Hannan, ‘White Mothers of Stolen Children Also Deserve an Apology’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 2010, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/white-mothers-of-stolen-children-also-deserve-an-apology-20101207-18o7t.html>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 21 | Felicity Collins & Therese Davis, Australian Cinema After Mabo, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2004, p. 112. |

| 22 | Paul Keating, ‘Speech by the Hon Prime Minister, P J Keating MP’, Australian Launch of the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People, 10 December 1992, available at <https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/original/00008765.pdf>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 23 | See Chris Salisbury, ‘Twenty Years On, One Nation Is Still Chaotic, Controversial and Influential’, The Conversation, 8 June 2018, <https://theconversation.com/twenty-years-on-one-nation-is-still-chaotic-controversial-and-influential-97247>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 24 | Simon Burgess, ‘One Nation and Indigenous Reconciliation’, in Bligh Grant, Tod Moore & Tony Lynch (eds), The Rise of Right-populism: Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and Australian Politics, Springer, Singapore, 2018, p. 146. |

| 25 | Australian Human Rights Commission, Bringing Them Home, 1997, <https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/pdf/social_justice/bringing_them_home_report.pdf>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 26 | John Howard, quoted in Janine McDonald, ‘Thousands Say Sorry, but Not PM’, The Age, 27 May 1998, available at <https://www.theage.com.au/national/from-the-archives-1998-thousands-say-sorry-but-not-pm-20210521-p57tyr.html>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 27 | Belinda Smaill, ‘Asianness and Aboriginality in Australian Cinema’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 30, no. 1, 2013, p. 89. |

| 28 | Nowra, op. cit., p. ix. |

| 29 | Perkins, quoted in Simpson, ‘An Interview with Rachel Perkins’, op. cit., p. 33. |

| 30 | Deborah Mailman, quoted in Ruth Hessey, ‘Ray of Light’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October 1998, p. 9. |

| 31 | Trisha Morton-Thomas, quoted in Hessey, ibid. |

| 32 | Theodore F Sheckels, ‘The “Stolen Generations” in Feature Film: The Approach of Aboriginal Director Rachel Perkins and Others’, in Belinda Wheeler (ed.), A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature, Camden House, Rochester, NY, 2013, p. 180. |

| 33 | Ceridwen Spark, ‘Gender and Radiance’, Hecate, vol. 27, no. 2, January 2001, p. 42. |

| 34 | ibid., p. 47. |

| 35 | Louis Nowra, cited in Spark, ibid. |

| 36 | Anthony Adah, ‘Agential Mortality: Death, Corporeality, and Identity in Radiance (1997)’, Post Script, vol. 24, nos 2–3, Winter–Spring/Summer 2005, p. 37. |

| 37 | David Malouf, cited in Catherine Simpson, ‘Notes on the Significance of Home & the Past in Radiance’, Metro, no. 120, 1999, p. 30, available at <https://metromagazine.com.au/notes-on-the-significance-of-home-the-past-in-radiance/>, accessed 31 January 2024. |

| 38 | Simpson, ibid. |

| 39 | Louis Nowra, quoted in Turcotte, op. cit., p. 39. |

| 40 | Anne Barnes, ‘Mapping the Landscape with Sound: Tracking the Soundscape from Australian Colonial Gothic Literature to Australian Cinema and Australian Transcultural Cinema’, Critical Arts, vol. 31, no. 5, 2017, p. 159. |

| 41 | Sue Gillett, ‘Through Song to Belonging: Music Finds Its Place in Rachel Perkins’ Radiance and One Night the Moon’, Metro, no. 159, 2008, p. 89. |

| 42 | Perkins, quoted in Turcotte, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 43 | See Andrew Smith, Gothic Literature, 2nd edn, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK, 2013 [2007], p. 14. |

| 44 | Gillett, op. cit., p. 89. |

| 45 | See ibid. |

| 46 | Adah, op. cit., p. 44. |

| 47 | Gillett, op. cit., p. 87. |

| 48 | Noel Pearson, cited in Rachel Perkins, ‘A Rightful Place’, Quarterly Essay, no. 56, January 2014, p. 82, available at <https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/correspondence/332>, accessed 21 February 2024. |

| 49 | Perkins, ibid., p. 83. |