When the Melbourne Theatre Company mounted a new production of David Williamson’s 1971 play Don’s Party in 2007, it was surprising to find how raw and challenging it still seemed.

In terms of ‘plot’, it is no more than a party given to celebrate what looks like an Australian Labor Party election victory, and the play traces the collapse of such hopes in tandem with the emergence of personal failures and frustrations. Perhaps the imminence of another federal election in which the ALP appears more clearly in the ascendant than for a decade helps to account for the play’s continuing freshness and ‘relevance’. It was also instructive to re-view the film, thirty-odd years after its appearance – and heartening to note that it retains its lethal edge. My concern here is the film, but it has a complex intertextuality which for people of a certain age will include the play itself; the recent Melbourne production means that the demographic in the know in this respect is larger than it might have been.

THE PLAY

According to Williamson:

The genesis of the play was simply a recollection that the last two election-night parties I’d been to were pretty dramatic and funny. Also, I was a fan of ongoing real-time action at that time … and thought a party would be an interesting thing to put on the stage.[1]Interview with David Williamson, March 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by DW).

Those in left-wing circles were generally dissatisfied with twenty years of conservative government, with a middle-class deference to Britain and the United States (some would say that the latter deference is still in place), with a relegation of women to subordinate roles, and with the Vietnam War still in full swing. In Williamson’s words, ‘The political and social climate of the time, in Carlton, was an anti-elitist left-wing orthodoxy.’ And Melbourne’s suburb of Carlton was crucial to the birth of Don’s Party, described in 1976 as ‘probably the most famous Australian play since Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll’.[2]Gordon Glenn and Scott Murray, ‘Production Report: Don’s Party’, Cinema Papers, March-April, 1976, p.339.

Don’s Party was first performed at the Pram Factory in Carlton, by the Australian Performing Group (APG) on 11 August, 1971. The Pram Factory was a key element in the revitalization of Australian drama in the late 1960s, along with La Mama – another, smaller Carlton theatre. The APG was a politically oriented theatrical company, disinterested in the conventions of middle-class, realistic theatre. Wilfred Last, the first ‘Don’, recalled:

It had taken its lead from American developments such as the Living Theatre and the Performance Group, from which it took its name, and was also influenced [inter alia] by Brechtian theatre and ideas. The Pram Factory was set up … to stage a play called Marvellous Melbourne, which was very different from the sort of plays David did …[3]Interview with Wilfred Last, March 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by WL).

According to Last, when Williamson first brought his script to La Mama, a couple of APG actors there rejected it in favour of a more polemical piece.

Williamson had enjoyed a success with his earlier play The Removalists (filmed in 1974) at La Mama. Graeme Blundell was the director of the APG at the time (he directed Marvellous Melbourne), and it was probably his contact with David Williamson that brought Williamson across from La Mama. Williamson remembers Blundell having to fight hard for permission to do it at the APG collective, where ‘the authoritarian hierarchy of writer and director was to be resisted by actors who should never be forced to mouth an attitude they didn’t believe in’. In Crashing the Party, a documentary about the film’s making, Phillip Adams remembers that Blundell had to sell the play to the APG as ‘a sad saga of bourgeois life’.[4]In Crashing the Party, a feature-length documentary accompanying the DVD of Don’s Party. Blundell himself, recalling ‘a certain amount of hostility to doing it within the group’, felt this arose from opinions such as, ‘It wasn’t experimental enough; it didn’t push back the frontiers of drama, and life; its political consciousness needed raising …’ and so on.[5]Graeme Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, Theatre Australia, Vol 1, No. 5 (1976–77), p.37. Once it was accepted by the APG, Last recalled that ‘the direction was pretty much under Graeme’s control; there weren’t any changes made to the script that I can remember’. What Williamson thought of as a ‘sprawling production, with actors wandering anywhere’, Last saw as a response to the staging challenges of the Pram Factory.

The play may not have been in line with the APG’s philosophy but it succeeded with Melbourne’s audiences. And its impact with Sydney audiences, when it was staged there at the Jane Street Theatre the following year, was greater. Its producer there was John Clark, and he had the advantage of more experienced actors. Clark’s ‘Director’s Note’, introducing the published play, records that, in Sydney:

The script continued to develop, in particular the political content of the play which Williamson uses so effectively both to mirror the declining personal hopes of his characters and to create an accurate sense of time and place.[6]John Clark, ‘Director’s Note’, in David Williamson, Don’s Party, Currency Press, Sydney, 1973, p.xi.

Clark goes on to say: ‘Yet when the final text of the play emerged, it was as precise, formal and finely orchestrated as a piece of music.’ This comment, in view of the shifting pairs and groups throughout the running time of play or film, makes one think that, in a tiny homage to Anthony Powell, it might be subtitled ‘A Dance to the Music of [a Very Short] Time’. Its sinuous windings as it focuses its attention first on this, then on another character, and on their uneasy, even volatile dealings with each other, suggest both recurring musical motifs and the patternings of dance. The ‘dance’ was performed at London’s Royal Court Theatre in 1976, cast mainly with Australians, including Ray Barrett and Veronica Lang – both of whom would later appear in the film. Barrett, who admired the play’s ‘vigour and frankness’, reports how, after a slow start, there ‘was standing room only for the last few performances’.[7]Ray Barrett, with Peter Corris, Ray Barrett: An Autobiography, Random House, Sydney, 1995, pp.181, 182.

The play’s development and its reception into Australia’s cultural consciousness offer fascinating ground for more detailed exploration than there is space for here. However, it is important at least to advert to the play’s place in recent theatrical history: when the film was made five years after that first Carlton performance, the play was still very much in the minds of the film’s audiences. As H.G. Kippax noted in his Preface to the first edition of the play, ‘Don’s Party is not a political play … Nevertheless, the play has political interest. Its sociological themes sketch some of the elements of change in the electorate.’[8]H.G. Kippax, ‘Preface to the First Edition’, in ibid., p.x. When the play was revived in 2007, its structure, of which Peter Fitzpatrick has given a subtle and persuasive account,[9]Peter Fitzpatrick, Williamson, Methuen, Sydney, 1987, pp.62–63. emerges as theatrically sturdy, and the play’s issues, partly though not wholly because of the political shifts in the air in 2007, retained much of their bite and relevance. The play, and the sociopolitical circumstances in which it had its being and its success, are significant intertextual influences on the film to which we now turn.

THE FILM

Production Dramas

Jack Lee

The first name to note in the production history of the film version of Don’s Party (Bruce Beresford, 1976) is that of English director Jack Lee. He had been a reasonably successful director in Britain, his career really beginning when he joined the GPO (later Crown) Film Unit in 1938, and winning a reputation as a documentary filmmaker. Post-war, he moved into features, enjoying major commercial hits with The Wooden Horse (1950) and A Town Like Alice (1956). As noted in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

In 1963 he went to Australia to live, and continued to work in documentaries, the best-known being From the Tropics to the Snow (1964), a send-up of tourist travelogues. From 1976 to 1981, he was Chairman of the South Australian Film Corporation, in which role he helped foster the careers of such directors as Bruce Beresford and Peter Weir.[10]Brian McFarlane, ‘Lee, Wilfred Jack Raymond’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition, 2006, <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/77340>.

Lee was interested in directing a film of Don’s Party, and approached producer Phillip Adams with this in mind; Lee confirmed this when I interviewed him for another purpose in Sydney in October 1990, when he showed no bitterness at the outcome of his approaches.[11]‘Jack Lee’, in Brian McFarlane (ed.), An Autobiography of British Cinema, Methuen/bfi publishing, London, 1997, pp.355–58.

Phillip Adams

Adams recalls that Lee ‘wanted to reactivate his career, but wasn’t sure how to go about this in the new Australian industry’. Adams persuaded him that the film couldn’t be got up with him on board, that the industry was too interested in its own new people. ‘And he just drifted off the project, except he remained co-owner of the property. He was never involved in the production.’[12]Interview with Phillip Adams, February 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by PA) While the industry at the time may well have been protective of its own burgeoning talents, it is also likely that the sixty-year-old Englishman might have found himself somewhat at sea with the intensely Australian cultural mores of this ‘ocker’ would-be-radicalism. Though Lee’s name does not appear on the final film, it is encrypted there in the credit which reads ‘Double Head Productions’, which essentially comprised Adams and Lee. As was customary with Australian films then, the majority of the production finance was provided by the Australian Film Commission with additional funding from Twentieth Century Fox. Adams now needed to find another director and canvassed several new talents of the local scene, including Ken Hannam, who had directed Sunday Too Far Away (1975), but ‘was out of sympathy with the urban characters … [and] found the dialogue too aggressive, too ugly’.[13]Quoted in Glenn and Murray, op. cit., p.341.

Bruce Beresford

‘I was told it was offered to various other Australian directors before it came to me …’[14]Interview with Bruce Beresford, February 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by BB).

Beresford’s first feature film as director was The Devil to Pay, made at Sydney University in 1961. After several shorts and documentaries, he directed the ‘ocker’ comedies, The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972, produced by Adams) and sequel Barry McKenzie Holds His Own (1974). Commercially popular, these were critically excoriated, and, as Adams said in Crashing the Party, ‘Bruce did need something redemptive’ after them. Peter Coleman records the vituperative responses of the local critics:

[The] attacks continued relentlessly despite the [first ‘Bazza’] film’s success, and Beresford’s career seemed finished … He simply could not find work as a director of feature films in Australia at a time when production was beginning to boom.[15]Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1992, p.60.

If Adams initially hesitated about Beresford as director of Don’s Party, it was because:

I didn’t think he was sophisticated enough for it, but, as we considered the scene at the time, I came to think he was the best prospect. He’s very bright intellectually, probably the smartest of his generation.

Beresford had returned to England to make the disastrous Side by Side (1975), dismissed by one reviewer as ‘this abysmal comedy’ without even the ‘exuberant vulgarity’ of the ‘Bazza’ films.[16]John Pym, ‘Side by Side’, Monthly Film Bulletin, March 1976, p.63. Of the telephone conversation in which Adams asked Beresford if he would like to direct Don’s Party, Beresford reported succinctly: ‘Phillip Adams saved my life.’[17]Quoted in Coleman, op. cit., p.61.

Problems And Decisions

Adams claimed the film had ‘a tormented production history’. Certainly there were major problems and challenges to be addressed before the cameras could roll.

Location

One of the first issues to be decided was where the film was to be set. Though the play began life as a ‘Carlton’ piece, Williamson had originally set it in Lower Plenty, a less distinctive north-eastern Melbourne suburb, in which it was reasonable to locate lower-middle-class aspirants to professional affluence. For the film, the production moved to Sydney, where, Adams felt, ‘… it would be easier to handle it financially, and to cast it’. Williamson was amenable to this, possibly recalling how Sydney audiences had ‘stamped the floor on opening night’. In a 1976 production report on the film, Adams said: ‘… we are filming on location in a New South Welsh version of Lower Plenty, but the domestic details are identical – down to the mandatory Breughel print.’[18]Quoted in Glenn and Murray, op. cit., p.342. The fact of moving to Sydney did not prove a serious problem but a more demanding locational challenge was the result of Beresford’s wish to film the action in a real suburban house. The decision ‘not to build a set but to borrow a house in Westleigh, Sydney … was at once cheaper and a way of reducing any lingering staginess’.[19]Coleman, op. cit., p.65. More ambitiously, Beresford also wanted to shoot not merely in a real house but also at night – and sequentially.

There was much to be said in favour of these decisions, but there was a matrix of tensions produced by the combination of the confinement of the shoot, the perversity of the wet February weather which made continuity difficult and led to covering the house with a marquee, and maybe the financial pressures which dictated a tight schedule. Actors used to more conventional daytime hours found the night-shooting wearying;[20]See Barrett, op. cit., p.188. there was virtually nowhere for cast or crew to escape each other’s society during the four to five week shoot; and as Adams puts it, there were ‘problems with actors locked in together with festering egos’. More positively, Graeme Blundell, playing Simon in the film, believed that ‘the ensemble thing grew during the rehearsal week’ in the house just prior to shooting.[21]Blundell, in Crashing the Party. However, writing in 1976 he had noted that ‘the real claustrophobia … created a hot bed of interpersonal tensions in the cast’.[22]Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, op. cit., p.37. In addition, the rain disrupted the sequential shooting in a way that would not have happened in studio-set filmmaking. This created difficulties for continuity personnel, and the plan to shoot in sequence had to be abandoned.

Opening out?

One of the earliest production issues to be resolved was the extent to which the setting and action of the play should be ‘opened out’ for the film. So often, such opening out looks like mere tokenism, no more than a gesture to film’s greater mobility in place and time. Take two prestigious films derived from notable American plays: Long Day’s Journey into Night (Sidney Lumet, 1962) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Mike Nichols, 1966). Lumet clung uncompromisingly to Eugene O’Neill’s claustrophobic setting, its characters locked in mortal love and combat; Nichols dissipated a potentially similar power by a fatuous mid-film break when the four characters are meaninglessly transported to a roadhouse.

There seems never to have been any aesthetic regret at largely confining the action of Don’s Party to the suburban brick-veneer house and the brief excursions outside its walls generally further our understanding of the characters. For instance, the early polling-booth segment firmly anchors the film to the party’s supposed raison d’être and provides the opportunity for a guest cameo to which I’ll return; the shot of Mack (Graham Kennedy) stocking up on beer at a drive-through bottle-shop confirms Kath’s (Jeanie Drynan) expectation of a ‘booze-up’; the brief shot of the womanizing Cooley (Harold Hopkins) lounging on a motel bed watching a non-election-oriented program, his half-naked girlfriend in evidence, suggests the extent of his political commitment; and, much later, a moment of wild driving by the surly dentist Evan (Kit Taylor) dramatizes his simmering rage. Adams remembers ‘discussion about opening the play out, to get it away from the claustrophobia of the house’, and that, as screenwriter, Williamson was receptive to suggestions. In the event, it is one of those play adaptations which makes intelligent use of opening out without sacrificing the essential tightness of the action.

Updating?

Everyone associated with the production seems to have been aware of the traps inherent in filming the play as a period piece – and of updating it to the 1975 elections. But none of the left-leaning personnel involved would, presumably, have cared for the idea of filming a party at which the expected catastrophic election, following the Whitlam ‘dismissal’, was the big-picture focus of the evening. Both play and film, despite dispiriting results on both personal and political party levels, depend on a kind of vigour and brazen, over-age laddishness that the characters would have found hard to sustain so soon after the dashing of their hopes, however trendily held.

There were negotiations with David about updating it, even perhaps providing a happy ending with the Whitlam government coming to power. David was always very good about such discussions, open to ideas.

While trying to avoid the impression of ‘period piece’, Williamson, ‘open’ as he may have been to such notions, says:

I don’t think I made any conscious changes to accommodate the passing of five years. It was always going to be the story of the 1969 election and the attitude and values of that time.

Apart from one or two small matters, such as house prices being at a slightly higher level for 1976, there is little evidence of updating for the film version.

Casting

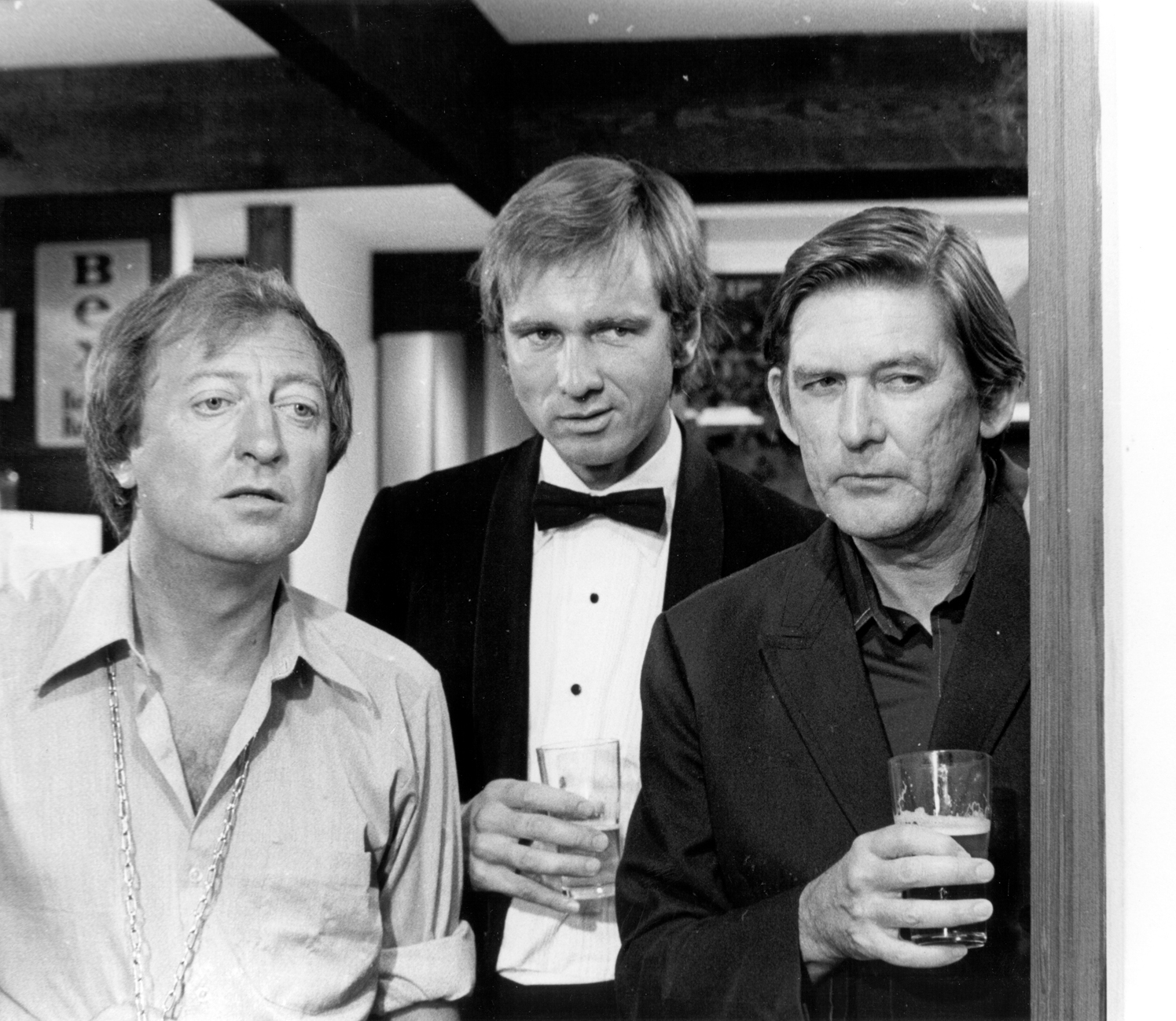

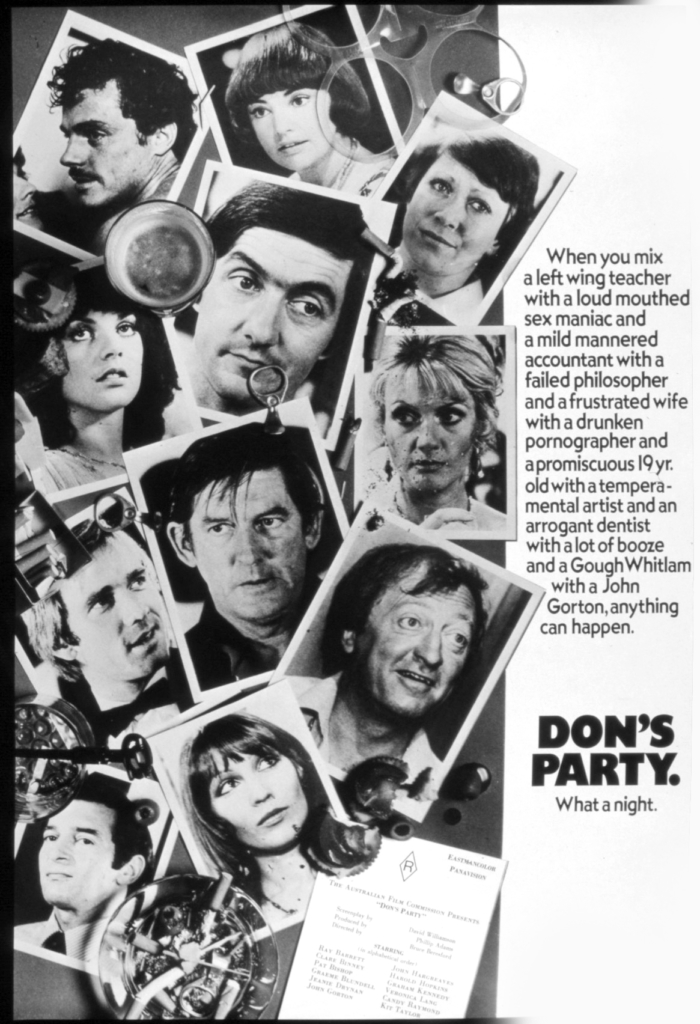

By 1976, there were scarcely any ‘names’ associated with Australian cinema, and Adams wanted to ensure a bit of box-office attractiveness by casting television personalities. Not necessarily known for their acting skills, these names could help to sell the film, in Australia at least. He wanted to cast Mike Willesee, the television compère, who, at 24, in 1966 was already a political correspondent and interviewer for TV’s This Day Tonight, and Germaine Greer, a very high-profile name by 1975. But nothing came of either of these. Adams also tried to negotiate for Paul Hogan, fresh from the Harbour Bridge, to play the lascivious Cooley, but his manager, John Cornell, ‘was worried that it might hurt their franchise. All that bad language and so on.’ Beresford remembered Hogan as ‘wanting a fee more than the whole budget’.[23]Beresford in Crashing the Party. Finally, Graham Kennedy, then a hugely popular TV personality with a genius for ad-libbing and holding a talk-show together, was signed to play Mack, who gets his kicks from watching (and photographing) other people engaged in intercourse with his wife. Kennedy was Adams’ choice; indeed, Beresford said: ‘I must have been the only person in Australia who hadn’t heard of Graham Kennedy.’[24]ibid. His hypothyroid eyes and sexually ambiguous persona made him apt and touching as Mack.

And speaking of sexuality, there were other casting problems in this regard. Beresford worried whether John Hargreaves’ gay sexuality would ‘show’, but Adams was confident Hargreaves could play Don as convincingly heterosexual. Adams and Beresford had wanted to cast Barry Crocker, star of the ‘Bazza’ films, as Don, but Crocker injured his back and had to withdraw at the last minute. Harold Hopkins, who finally played Cooley, recalled in Crashing the Party that he felt Beresford ‘had a thing about gay people’.[25]Harold Hopkins in ibid. Whether or not that is mere speculation, Adams also claims that homosexuality among the actors created problems and tensions in the confinement of the location-shooting in the suburban house, recalling that Kennedy ‘came in for some homophobia. One of the actors, who’d probably had too much to drink, turned on Kennedy and called him a “screaming little queen”’. Kennedy’s biographer, Graeme Blundell, records that there was tension between Kennedy and Ray Barrett (playing Mal):

[At first] they appeared to get along well … But as the film shoot cranked along, the rooms in the house at Westleigh growing increasingly hot and humid, Graham began to find Barrett’s jokiness, his old-style repertory theatre bonhomie tedious.[26]Graeme Blundell, King: The Life and Comedy of Graham Kennedy, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2003, p.324.

Finally, according to Blundell, ‘Graham suddenly looked up and in a loud voice said, “Look, fuck off, Ray.”’[27]ibid. Arguably, such tensions fed into the film’s increasingly acrimonious exchanges, and help to make the film such an invigorating experience, even though it – like the play – is about two ‘party’ failures.

Kennedy himself was modest about his acting capacities. Expecting to be surrounded by other television names that fell by the wayside, he recalled: ‘So it left me with all these proper actors. And I was horrified and frightened beyond words.’[28]Quoted in ibid, p.323. Adams’ choice of Kennedy was vindicated in the reviews which habitually singled him out from the ensemble. Apart from Kennedy, probably the best-known name in the cast was Barrett, whose craggy-featured, effortlessly authoritative persona had made him a household name in Britain in such well-regarded series as The Troubleshooters (1966–71).[29]British Television (compiled by Tise Vahigami), Oxford University Press, 1996, praised it for its ‘sharp and well-defined scripts [which] made this one of the more exciting mid-1960s drama series’, p.138. From some accounts (for example, Blundell’s) of the production history, one detects a possible chauvinism in regard to ‘returning’ actors. Barrett had played Cooley in the London production of the play, but was too old for this role in the film, in which he is brilliantly cast as Mal, but Veronica Lang, Jody in the London production, repeated her role in the film.

The only actor from the Australian productions of the play who also appeared in the film was Pat Bishop, who had played Kath in Sydney in 1972 and plays Mal’s angry, dispirited wife Jenny in the film. Jeanie Drynan was cast as the film’s Kath as a result of Beresford’s having serendipitously seen her in an episode of The Class of ’74, while staying at a motel in Arizona. Adams wanted Wendy Hughes for the sophisticated artist, Kerry, but later praised the ‘forensic fierceness and precision’ that Candy Raymond brought to the role.[30]Adams in Crashing the Party. And Graeme Blundell, who had directed the first production of the play in Melbourne, plays Liberal-voting Simon, for whom the party is an ordeal. Despite the fits and starts and the production difficulties, a fine ensemble was achieved.

Finance

There is a good deal of casual talk about how much the film cost and it is always hard to be certain about the financing of films. Cinema

Papers reported that the ‘entire film is being made on location in Sydney, and with a budget of $275,000’.[31]‘Production Report’, Don’s Party, op. cit., p.339. In a subsequent issue, the journal gave $300,000 as the figure.[32]‘Production Survey’, Cinema Papers, #10, September-October 1976, p.160. This was apparently the publicly listed budget, and is confirmed by David Stratton in his account of the 1970s revival.[33]David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, Sydney et al, 1980, p. 307. Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper’s landmark chronicling of Australian film production to 1977 has this to say:

Private investors in the $270,000 production included several independent exhibitors … and the remainder of the production cost was covered by the Australian Film Commission and a small investment from Twentieth-Century-Fox [sic].[34]‘Don’s Party’ in Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980 (revised edition 1998), p.305.

For those still following or caring about these figures, it should be noted that an exhaustive 1987 study claims that the film’s budget was $300,000 (adjusted to 1982 figures, $538,500), and that by January 1980 it had earnt $279,139 in rentals.[35]Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia, Vol.1: Anatomy of a Film Industry, Currency Press, Sydney, 1987, p.224, 222. Whichever figure is nearest the mark, Don’s Party wasn’t a very expensive film to make, but of course this could be said for most Australian films of the period. Even so, it was inexpensive as compared with several other films shot in the same or following year (dates refer to year of shooting, not of release): Eliza Fraser (Tim Burstall, 1976, $1,200,000), The Picture Show Man (John Power, 1976, $600,000), The Mango Tree (Kevin James Dobson, 1977, $800,000), The Last Wave (Peter Weir, 1977, $860,000), Newsfront (Phillip Noyce, 1977, $600,000) and the next Adams–Beresford collaboration, The Getting of Wisdom (1977, $575,000). It is easy to see why Don’s Party was comparatively cheap: it didn’t depend on imported stars or special effects or multiple locations. It makes its modest budget work hard in the interests of what matters; the money is there on the screen in performance and cinematography and fluidly intelligent direction.

Contexts

No film exists in a vacuum. It will be produced in a particular industrial climate, within the parameters of filmmaking practice at the time, and in a particular sociopolitical frame of reference. Such extra-textual matters will, to varying degree, bear on the finished film: it will be a different film because of the influence of such factors. We may respond differently to the film of Don’s Party, made in 1976, from how we would have if it had been made ten years later.

Politics and all that

The election of October 1969 is clearly a significant element in the film’s fabric. If you are too young to remember this election, and are keen to come to terms with this film, it would be helpful to find out what the anticipatory feeling was, and to try to imagine how much this might have been in the minds of the theatre-going public at the time of the play’s first appearance. A major starting point for the film is the growing dissatisfaction among middle-class, educated voters with the twenty-year Liberal dominance – the Liberal Party holding its ascendancy partly because the Catholic-based Democratic Labor Party gave its preferences to the Coalition. There seemed to be a palpable swing towards the ALP in the lead-up to the election. The protagonists were ALP leader Gough Whitlam and Liberal leader John Gorton. Of the two men, Phillip Adams said: ‘Gough, with his patrician air, always looked as if he’d strayed in from the Liberal Party, whereas Gorton looked like a scruff.’

As the votes are counted and the tally-room reports come through during the evening of the play/film, it is clear that Labor is not going to win, and the more or less affluent left-wingers, at first loudly proclaiming their political allegiance, become more and more despondent. It also becomes clear that their apparent political disappointments matter less to them than their personal failures, professional and sexual. As Kippax wrote: ‘David Williamson’s play reflects the hopes and then the frustrations of Labor supporters on that night of suspense.’[36]Kippax, op. cit., p.vii. So does the film, resisting the temptation to update the action. And, in the light of the imminent election as I write, many people, according to opinion polls, are hoping for a similar change of government (after only a decade in this case), giving the film, and the recent Melbourne production of the play, a special piquancy.

In more broadly ‘political’ – perhaps more accurately ‘cultural’ – contexts, one might draw attention to other changes occurring in Australian society that make their influence felt in the film. The play’s setting is 1969, a year before Germaine Greer’s groundbreaking book The Female Eunuch appeared, but the play itself was first performed in 1971. It would therefore have been difficult for a politically aware audience, confronted with various kinds of justified female discontent, not to have contextualized this in the broader dissatisfaction with ‘the systematic denial and misrepresentation of female sexuality by a male-dominated society’.[37]Magnus Magnusson (ed.), ‘Greer, Germaine’, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, W & R Chambers, Ltd, Fifth Edition, Edinburgh, 1991, p.624. The women in the play are in varying degrees exasperated with being put-upon in the interests of husbands’ careers or are determined to assert their sexual independence. The film reviewer who claimed that ‘behind it all Williamson is pin-pointing a staleness in marriage, class snobbery, the permissive age, problems of on-coming middle-age and unfulfilled pipedreams’,[38]Raymond Stanley, ‘Don’s Party’, Cinema Papers, Issue 11, January 1977, p.266. was properly alert to the kind of malaise disturbing the educated middle classes, and those who’d made their way from the lower-middle. Especially, though, in relation to women: Williamson may not have had the imminent ‘women’s movement’ consciously in mind when he wrote the play, but in 2007 he said:

It [the setting] was a year before … The Female Eunuch was published … the women couldn’t articulate the anger they were feeling as the women’s movement wasn’t fully underway. The sexual mores of the late 60s in the US had filtered through to Australia, and the short-lived idea that sex could be treated as a game or sport was still current. Feminists were soon to declare that this was just another method of male exploitation.

When one considers the way the film represents the women, it is interesting to see whether the five years separating the film from the play’s inception have, without conscious ‘updating’, nevertheless registered the potent seething of women’s discontent during the intervening years. About the original play script, Blundell wrote in 1976 that ‘time was also spent attempting to fill out the women’s roles as it was generally felt … that they were somewhat one-dimensional and unconvincing’.[39]Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, op. cit., p.37. By the time the film appeared, though the male roles still occupy the foreground most of the time, the women make very strong impressions. Adams is right to say: ‘They were often moving; there’s real pain in their attacks on the men.’ These are women tired of maintaining houses and bringing up children, as if that was meant to be enough to satisfy their aspirations; or they are women demanding autonomy over their own bodies.

A new Australian cinema

There is not the space here – or need – to do more than refer to the climate of burgeoning hopefulness in Australia’s film industry at the time Don’s Party was made, but a couple of points should be made.

(I) John Gorton

Adams insists that when it came to the revival of Australian cinema, ‘the accolades to Gough Whitlam were misplaced’. For Adams, ‘The revival wasn’t a matter of continuity with earlier agitation: it grew directly out of Gorton’s response to the idea that we were losing the chance of an industry.’ Gorton, who became prime minister in December 1967, sent Adams, university lecturer Barry Jones and Liberal politician Peter Coleman (later Beresford’s biographer) on a world trip to study government-funded film and television industries. Following their Interim Report, Gorton promptly announced an allocation of $300,000 to establish the Experimental Film and Television Fund (EFTF) and an Interim Council for the Film School. A full account of the processes surrounding the industrial revival can be found elsewhere.[40]See, for instance, David Stratton, op. cit.; Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, op. cit.; Brian McFarlane, Australian Cinema 1970-1985, Secker & Warburg, Ltd, London, 1987. The cameo given to Gorton in the early polling-booth scene in Don’s Party earns its place on grounds of verisimilitude; it is also a tribute to his crucial role in instigating the revival, and a graceful acknowledgment of a major viewing context for the film.

(II) The ‘Ocker’ heritage

One of the definitive features of the early days of the ‘revival’ was the commercial success of the ‘ocker’ comedies. Two 1971 films, Walkabout (Britain’s Nicolas Roeg) and Wake in Fright (Canadian Ted Kotcheff), were both so skilfully made that they might have launched the revival, but were respectively too poetic and too abrasive to command wide audiences. Instead, a series of comedies built around variations on the ‘ocker’ image of the Aussie male, as irreverent, beer-swilling, with a leery eye for the sheilas, caught the popular fancy. These films, generally deplored by the critics who were holding out for something more tasteful, were Stork (Tim Burstall, 1971), The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, Alvin Purple (Tim Burstall, 1973), Alvin Rides Again (David Bilcock, Robin Copping, 1974) and Barry McKenzie Holds His Own.

Don’s Party depicts certain ocker characteristics, but not in a mode of celebration or indulgence. The guzzling, groping men in Don’s Party are not reclaimed for intrinsic lovability: the view of them we take away is apt to be as their women see them, and it’s not a pretty picture.

All these ‘ocker’ films made money, sometimes more than twice their budgets. Whatever their aesthetic merits, they undeniably created and supplied a local market for indigenous product. As Adams found when he came to place Don’s Party, this was not something that followed as the night the day. Don’s Party depicts certain ocker characteristics, but not in a mode of celebration or indulgence. The guzzling, groping men in Don’s Party are not reclaimed for intrinsic lovability: the view of them we take away is apt to be as their women see them, and it’s not a pretty picture. The film is sometimes grouped with the ocker comedies but this seems a failure to note its point of view: insofar as the ocker comedies are an important contextual element, it is a matter of satirical deconstruction, not a continuation of the japes. In the context of Beresford’s career, it is a watershed between his work on the ocker comedies and the tougher assignments that followed – including The Getting of Wisdom (1977), Money Movers (1979), Breaker Morant (1980), The Club (1980), Puberty Blues (1981) – all films exploring diverse hierarchical structures.

(III) The literary cycle

If the ocker comedies got the revival moving, it was the decorous adaptations of classic and/or popular Australian literary works, especially novels, that brought it serious réclame. Above all, it is probably Peter Weir’s swooningly elegant version of Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) that most people associate with the renaissance of the Australian film; and it was followed by other respectful adaptations such as The Getting of Wisdom, The Mango Tree, The Irishman (Donald Crombie, 1978) and My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979). These films, along with the critically applauded original screenplay Sunday Too Far Away, offered ripostes to the ocker comedies.

Don’s Party is obviously an adaptation, and of a distinguished and popular antecedent, but it doesn’t otherwise have much in common with this literary strain: it is tonally different from them, as it is from the ocker comedies with which, superficially, it may appear to have more in common. And it is, in terms of filmmaking know-how, at some remove from the preceding Williamson adaptation, The Removalists (Tom Jeffrey, 1975), which failed to shake off its theatrical origins. One reviewer wrote that Williamson’s skill with dialogue ‘does not cancel out the difficulties associated with making a film out of a play. The Removalists still splits naturally into acts’; and that it does not ‘overcome the fact that film conditions you to want more movement than you get from two sets and a couple of street scenes’.[41]Sandra Hall, Critical Business: the New Australian Cinema in Review, Rigby Publishers, Adelaide et al, 1985, p.101. Another reviewer claimed that ‘the film hardly escapes its theatrical origins and here the very obvious sets are much to blame’.[42]Stratton, op. cit., p.120. It is worth bearing these comments in mind in relation to the film of Don’s Party, with its much publicized location-shooting in an actual house.

On screen

Around the time of the film’s release, Bruce Beresford wrote:

David Williamson was aware of the differences between the two mediums. He understood the capability of the cinema to convey nuances of behaviour and had cleverly reworked a number of dialogue encounters so that the overall length was substantially reduced but the content remained the same.[43]Bruce Beresford, ‘Don’s Party from Play to Film’, Theatre Australia, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1976-77, p.33.

Williamson himself believed that:

Film made the flow of the party easier because of its ability to focus on sub-groups. The screenplay replaced a lot of words with images and … I was already aware that film can’t take the weight of dialogue that the stage can.

Bearing in mind those assessments from two of the key collaborators, I would say at once that the film maintains a remarkable fluidity of movement among the participants as the various groups form and re-form. According to Beresford, ‘Apart from being moved about the house there wasn’t much that could be done to adapt the play [to film],’ but that is too modest an account. He has orchestrated those movements around the house in such a way as to ‘spotlight’ (a theatrical metaphor) a particular sub-group at any given time, with telling glimpses of others in the background, so that there doesn’t seem anything forced about the process. In this, he is hugely abetted by cinematographer Don McAlpine whose camera tracks and pans and tilts with unobtrusive skill to highlight, first this, then that, group or person.

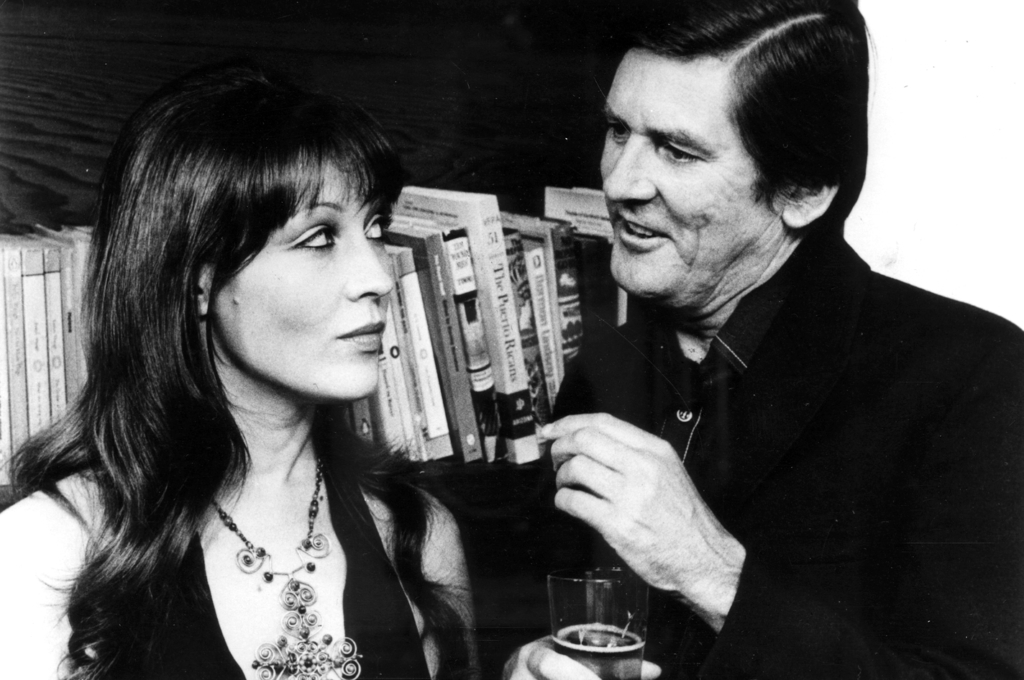

One still gets the impression, as noted previously in relation to the play, of a skilfully choreographed dance in which partners change regularly, overtures, often sexual, are made, acceded to or rejected. Those sitting out a particular movement of the dance are often seen to be watching the steps of the others with responses ranging from embarrassment through contempt to anger. Consider, for example, the sequence in which the sullen Evan and his elegant artist wife Kerry (Candy Raymond) arrive. They are dressed with more sophistication than the earlier guests, and there is from the start a prickliness between them. When someone mentions sardonically that middle-class home-owner’s delight, ‘renovating’, Evan snaps, ‘I like renovating’, introducing at once an aggressive note. His political affiliations are kept ambiguous until a post-bathroom conversation with the hapless Simon, who’s hoping to find an ally in Evan – he looks more like a Liberal voter than the other men. While Evan and Kerry are being introduced into the party, they are eyed by Don, Mal and Mack, who wonder about ‘having a go’ at Kerry. Like the accompanying music at a dance, the TV is heard to announce ‘a marked swing to Labor’. As if buoyed up by the larger optimism, Mack moves to Kerry. ‘Certain men are going to offer themselves to you tonight’, he tells her. After her discouraging reply, Mack cedes to Mal who begins his pitch: ‘Your physical beauty could cause trouble … It could place your marriage under strain’. During this unequal colloquy the camera slyly sidles round the room. Kerry drifts off, leaving Mack to crow at Mal, ‘You can’t win ’em all.’

This sequence is typical of much of the film’s modus operandi, and one can’t help thinking how much more easily film can handle this kind of brick-veneer cotillion than the stage can. It is nicely apt that the Oxford Companion to Music writes of the ‘cotillon’ [sic]: ‘In the course of the dance almost every gentleman would dance with almost every lady.’[44]Percy A. Scholes, The Oxford Companion to Music (1938), Oxford University Press, London, 1963, p.258. That goes some way to illuminating the structural arrangement of the film, except that, unlike in the stately procedures of a nineteenth-century ballroom, the shifting ‘sets’ here are also sometimes all-male, sometimes all-female. Whatever the gendered constitution of the foregrounded set, though, there is always the authenticating sense of others – observers, escapees and the ignored – hovering behind and around.

The dance analogy is appropriate also in that it implies pattern, and the film, for all its air of contemporary malaise and fragmentation, is actually very powerfully structured in several ways. It takes from the play, of course, the spinal structuring effect of the political party’s buoyancy and downfall and encourages us to see this as commentary on the other party, with its displays of bravado giving way to recrimination and awareness of failed ambitions. This parallelism governs our over-all response to the film, as the evening loses its punch and settles into acrimony and lethargy.

The film is underpinned by another sort of parallel: that among the various couples. Each of these is characterized by a striking inequality: teacher and would-be novelist Don is married to the deeply resentful Kath; the ageing blowhard Mal is matched with the soured-off Jenny; archetypal middle-class dentist/renovator Evan wants more control over sexy, ‘artistic’ Kerry than he has a hope of achieving; womanizing Cooley’s bimbo, Susan, turns out to have a mind as well as ‘melon breasts’; and even the Liberal-voting couple, Simon and Jody, will reveal flaws in their image quite early in the evening, and she will eventually try her charms on Mack whose real turn-on is voyeurism. In the film’s remarkably fine ensemble cast, this kind of parallelism is there in the look, and looks, of the members of each couple, the screen making use of close-ups to underscore, say, Kath’s growing anger with Don, or Jody’s vapid rising to the intrigue factor of the evening’s louche offerings.

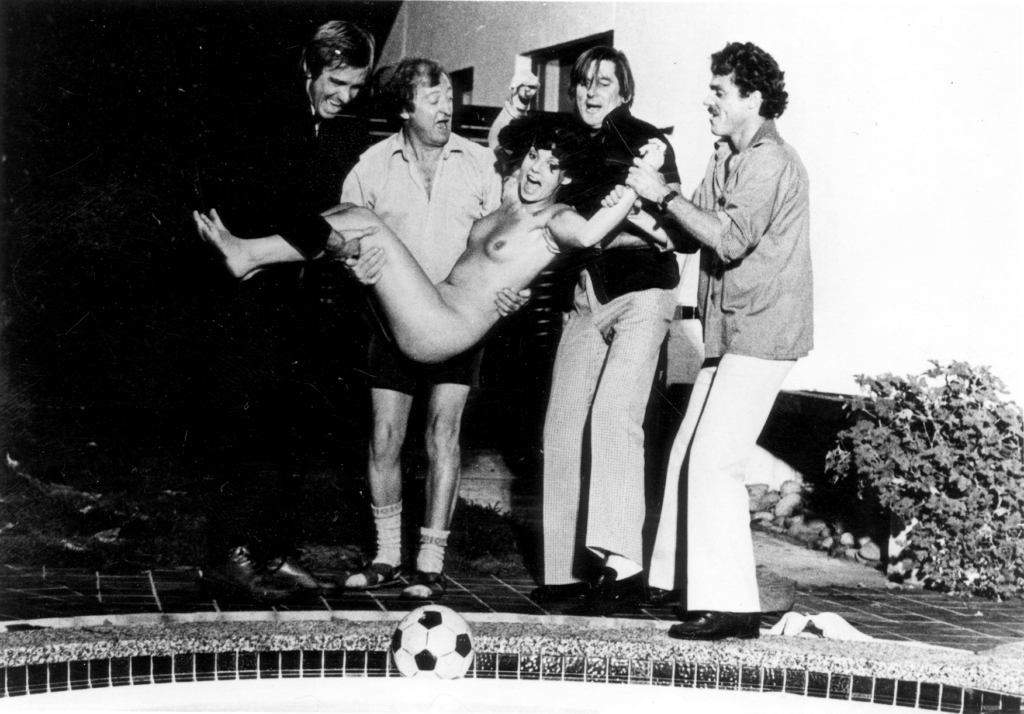

And in another lesser set of parallels, three of the men are put to humiliating flight – Evan and Simon flinging out of the party without their wives who have found other interests, and Cooley running around in his underpants when the outraged Evan finds him with Kerry in ‘one of a man’s most intimate moments’. As for the other three men, Mack is asleep on the floor, and Mal and Don (in two utterly knowing performances of windy self-delusion by Ray Barrett and John Hargreaves) are slumped boozily on beanbags, recalling ‘great days’ in a manner which led Adams to say that ‘Williamson was always conscious of repressed homosexuality in all male friendships’. The men have not emerged well from the evening’s shenanigans. They look foolish in their near-nudity after the swimming-pool sequence and it is almost as if this is a signifier of their basic ordinariness: suggesting King Lear’s ‘poor, bare, forked animal[s]’.[45]William Shakespeare, King Lear, Act 3, Scene iv, l.96. They rouse only mild sympathy for the exposure of their unadorned selves, pretensions stripped away.

The final structuring touch I want to draw attention to is the way in which the film begins and ends with Don in the garden: at the start as he contemplates the day of victory ahead; at the end dejectedly surveying the wreckage of one of his fruit trees, as Kath calls him to bed. What I am suggesting here is that Don’s Party is, for all its apparent casualness, rigorously put together. Its parallels work, sometimes subtly, sometimes boldly, to highlight the shibboleths of these middle-class lives, the affluence of which doesn’t paper over the cracks through which seep myriad discontents.

The film gains immensely from resisting the temptation to ‘open out’ just because it can. The above-noted brief examples all seem dramatically justified, in the sense that they add to our understanding of the characters involved. The main sequence devised for the film is that in which the men first kick a soccer ball around in the garden, and merely to move into the garden is not necessarily a serious break with the play’s confinement of the house. Then, the ball having gone over the fence to the absent Liberal-voting neighbour’s pool, the men, behaving with full male chauvinist abandon, strip Susan and throw her in. Don jumps in fully dressed, the other men follow his lead but strip first. There is a potent sense of the party’s getting out of control, this feeling reinforced by the movement, not merely outside the house but into another yard, into the ‘enemy’s territory’. Significantly, it is when they return from this brief liberatory excursion that Cooley turns on the naked Don and Mal and spits out contempt for their hypocrisies and pretensions. At this low point in the evening, Kath throws their clothes at them, returns to the women and says, ‘All they ever do is hand out a few how-to-vote cards’, and the ‘dance’ moves to the women talking about the men’s sexual prowess and limitations.

Don’s Party parallels work to highlight the shibboleths of these middle-class lives, the affluence of which doesn’t paper over the cracks through which seep myriad discontents.

There isn’t space here to go through the whole film in this kind of detail. It is enough to say that Beresford and his cast maintain a firm grip on the growth of tensions, sexually- and gender-based. Not one of the five pairs is intact at the end of the night, or, rather, if intact, as in the case of Don and Kath, it is as a result of accepting frustrations rather than having worked through them. The various confrontations are directed and acted with perception and a sure sense of climaxes.

Given the film’s pervasive realism in a confined space, only two moments fail to ring true to me. Kath is presented as a hostess, however reluctant, who conceives her function as being to look after her guests. So it is hard to accept the cruelty of her laughing at Simon’s discomfort as he storms out, having mis-buttoned his safari-suit jacket, or her turning on Jenny in the matter of Jenny’s extravagance and financial debt. Against these false notes, though, one sets the poignancy of Jenny’s breaking down, for which she elicits some passing sympathy from Don, Kath’s bitter outburst about having had to wait seven years for a baby, and Mack’s lonely kinkiness. Virtually all the acting is excellent, and it is probably no more than a matter of firsts among equals to distinguish Pat Bishop’s Jenny, who shocks with the rawness of the feeling she gives voice to, Jeanie Drynan’s Kath and Graham Kennedy’s Mack. Graeme Blundell’s Simon has less to work with than the others – he is mostly set up as a target for left-wing scorn. But making bricks with less straw than the others, he can cause one to feel for his isolation among what he charitably calls ‘a pretty extrovert lot’ and what Evan succinctly describes as ‘a bunch of shits’.

It’s not just a matter of the actors, confidently in command of their material, or of the fluidity of direction and cinematography as already noted. One should note also the editing skills that direct our attentions to the key faces or groupings at key moments, and the production design (the inevitable Breughel; the details of furnishing, like the awful beanbags) and the costumes, memorializing a sartorial era most of us who lived through it would rather forget. In such matters as these, Stratton is right when he says: ‘… making a film in 1975 which was set in 1969 created a lot of problems; it was too close to be a period piece but still far enough away for mistakes to be made.’[46]Stratton, op. cit., p.49. In this respect it is hard to fault the film, and overall Beresford has taken a very sturdy theatrical piece and made an equally sturdy film version of it.

Reception

In his biography of Graham Kennedy, Graeme Blundell wrote: ‘The film of Don’s Party was well received and, combined with the success of the play on which it was based, even passed into the language as an expression.’[47]Blundell, King, op. cit., p.326. Yes, but the film’s reception only came after producer Adams’ efforts to get it seen. Whatever critical interest there was in new Australian cinema, it was not easy to get the films booked into major exhibition chains. According to Adams:

The producer’s role kicks in with post-production, especially with arranging release. No one wanted Australian films at the time … I got a booking in the Capitol, a lovely old theatre in Melbourne. I couldn’t get a distributor, but then found another cinema in Melbourne, the Bryson in Exhibition Street, that was desperate for product, so I booked it there.

The Sydney release was delayed because Fred Schepisi’s The Devil’s Playground (1976) was running so well at the Ascot, the independent cinema Adams had recommended to him. Don’s Party then had a reasonably popular run in Australian metropolitan centres, and went on to distinguish itself in the Australian Film Institute Awards for 1976 releases. The film won five times: Director, Screenplay, Actress (Pat Bishop), Supporting Actress (Veronica Lang), Editing (William Anderson).

The film was successfully shown at the San Francisco and Berlin Festivals in 1977, and Filmnews reported that ‘F.J. Holden and Don’s Party were the success stories of the [Cannes 1977] festival’ in the sense of racking up overseas distribution sales.[48]‘News from Cannes’, Filmnews, June 1977, p.5. Cinema Papers reported sales to Israel and six South American countries.[49]‘Territories Sold at Cannes’, Cinema Papers, Issue 13, July 1977, p.33. However, its UK cinema release didn’t happen until early 1979 and its US release was delayed until 1982, by which time Beresford was known for The Getting of Wisdom and Breaker Morant. When Don’s Party did open across the US, it was widely and positively reviewed, from New York to Seattle, from Washington to Los Angeles. Such notable critics as Andrew Sarris in The Village Voice and Vincent Canby in The New York Times were strong in their praises and were quoted in a full-page ad in Variety (9 June, 1982).[50]For those interested in following up the overseas reviews, the Australian Film Institute library has a prolific cuttings file on the film (and on many others). This ad made much of the fact that the film broke box office records at the D.W. Griffith Theater in New York. In time, its US distributor, the Satori Entertainment Corporation, would be successfully sued by the Australian Film Commission which was awarded $US100,000 in May 1987 in compensation for Satori’s ‘dishonest accounting’.[51]Judge Thomas Griesa, in the US District Court, New York, quoted in Brisbane Courier-Mail, 5 May 1987. Whether David Stratton was wholly correct to say that the film ‘succeeded with the public and easily covered its costs’[52]Stratton, op. cit., p.48. would be challenged seven years later by Dermody and Jacka who wrote: ‘A number of pre-tax films such as Don’s Party and Newsfront did manage to edge into profit years after initial release, through the slow returns from overseas and art-house circuits.’[53]Dermody and Jacka, op. cit., p.184.

When the film was finally released in Britain, it received generally favourable notices from Monthly Film Bulletin (‘Bruce Beresford orchestrates … with enjoyable brio’[54]Tim Pulleine, Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1979, p.22.) and Films and Filming, which, in a long, analytic review, praised it for its ‘sharp observation of human nature.’[55]Eric Braun, Films and Filming, May 1979, p.37. Among newspaper reviewers, Alexander Walker in the Evening Standard found it ‘savagely funny’, the Financial Times critic thought its ‘satirical edge [was] knife-sharp’, while Patrick Gibbs in the Daily Telegraph found the people dislikeable and the taste sour but had ‘no reservation’ about the quality of the acting.[56]See AFI cuttings file on the film. Walker and The Financial Times critic were quoted in The Sunday Telegraph (Sydney), 22 April 1979; and Gibbs were reported in both The Herald (Melbourne), 21 April 1979 and The Canberra Times, 23 April 1979. In both Britain and the US, there was a sense of reviewers being startled by the boldness of the language and the men’s behaviour. However, praise for the acting, direction and Don McAlpine’s cinematography was almost universal, particularly in relation to the film’s skill in negotiating its confined setting.

Local reviewers were guarded in their praise, perhaps because the film seemed neither ocker comedy (it submits ockerism to savage scrutiny) nor respectful adaptation and/or period piece of the kind that had brought prestige to the local industry. Several reviewers compared the film with the play to the film’s detriment. Sandra Hall, in The Bulletin, somewhat bafflingly wrote:

The play is able to work on several levels by keeping more than one strand functioning at once, each a comment on the other. Superficially, the film does the same, but the cinema’s great tool, the close-up, works against this by breaking up the set and providing an intimacy that the play doesn’t need.[57]Hall, (reprinted in Critical Business, op. cit.), p.58.

One might quibble over several locutions there, but it’s enough to draw attention here to the last clause, ‘that the play doesn’t need’, to indicate that Hall hasn’t made the necessary leap into understanding how Beresford’s film works as a film. Cinema Papers’ reviewer concluded a meandering account of the film: ‘For those who have not seen the play, the film will probably be satisfying; others who have are likely to be disappointed.’[58]Stanley, Cinema Papers, op. cit., p.266. Geraldine Pascall, however, writing in The Australian, praised the film’s ‘success in translating the play into a movie’, claiming that ‘director, writer, camera and cast manage it with admirable professional skill’.[59]Geraldine Pascall, ‘Full frontal male ignominy’, The Australian, 6 December 1976. These comments suggest that adaptation theory had a long way to go in 1976, though there is no guarantee, despite its repudiation of ‘fidelity criticism’ or insistence on comparative evaluations, that its advances have had the slightest effect on reviewers.

There have been plenty of critical reappraisals since then (see Dermody and Jacka, Tom O’Regan, Jonathan Rayner and others listed in the bibliography). One of the most provocative came from Robin Wood, who analysed the film as an attack on ‘the monstrousness of the heterosexual male as lord-of-the-universe’, calling into question ‘the fundamental structures of patriarchal capitalist society’. Wood, who admired Beresford’s next film, went on to say, ‘The clear feminist impulse that animates Don’s Party and The Getting of Wisdom makes Beresford’s subsequent career the more unaccountable.’[60]Robin Wood, ‘Quo Vadis Bruce Beresford?’, in Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan, An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985, pp.200, 201, 202. There is characteristically intelligent, wide-ranging commentary in Wood’s essay, but, as for finding Beresford’s later career ‘unaccountable’, that is open to query. Does Wood suggest that the director had an obligation to pursue a similar Marxist-feminist path or to risk the imputation of inconsistency – or worse? Part of the interest of Beresford’s work is, alongside some recurring thematic concerns, a maverick refusal to be contained by genres or ideology. His filmography of now nearly three dozen titles has its share of duds (remember King David [1985]?), but there is enough sense of venturesomeness, along with unpretentious craftsmanship, to make one forgive these as falterings in the larger picture. A man who has gone from Don’s Party in 1976 to adapting Oscar Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance thirty years later may not be done with surprising us.

FROM THE NFSA

For the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA), Don’s Party is important from a number of perspectives:

Don’s Party was made by a significant Australian director, it encapsulates significant ideas and debates in relation to ‘being’ Australian and has an important place in the renaissance of Australian filmmaking.

So says David Noakes, project manager of the Atlab/Kodak Cinema Collection at the NFSA:

Plus 1976 was a watershed year for the Australian film industry as significant films like The Devil’s Playground [Fred Schepisi], Caddie [Donald Crombie], Storm Boy [Henri Safran], and the less known but influential Pure Shit [Bert Deling] and Queensland [John Ruane] were all produced in that year.

The NFSA recognizes Don’s Party as part of a strong post-1970 stable of Australian stage adaptations to film, many of which were penned by David Williamson.

Working with Atlab Australia, the NFSA created a new intermediate on Kodak Polyester stock. ‘This allowed us to capture the images before the acceleration of fading which overcomes all film stock,’ says Noakes. Atlab also re-mastered the mono sound mix to Dolby (mono), ensuring respect for the original sound balance and presence.

These new materials have allowed NFSA to create new prints that have stabilized the fade and allowed the film to be screened on modern projectors with Dolby playback.

Educational bodies can access Don’s Party and other films through the National Film, Video and Lending Service collection that is managed by the NFSA. For further details, see <http://www.nfsa.afc.gov.au/nfvls>.

Clips from Don’s Party and study notes can be found on the australianscreen website: <http://www.australianscreen.com.au>.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

(NB: See endnotes for details of individual contemporary reviews and short newspaper items.)

Ray Barrett (with Peter Corris), Ray Barrett: An Autobiography, Random House, Sydney, 1995.

Bruce Beresford, ‘Don’s Party from Play to Film’, Theatre Australia, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1976-77.

Graeme Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, Theatre Australia, Vol 1, No. 5. 1976-77.

Graeme Blundell, King: The Life and Comedy of Graham Kennedy, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2003.

Tim Burstall, ‘Twelve Genres of Australian Film’, in Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan (eds), An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985.

John Clark, ‘Director’s Note’, in David Williamson, Don’s Party, Currency Press, Sydney, 1973.

Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1992.

Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia: Anatomy of a Film Industry, Vol. 1, Currency Press, Sydney, 1987.

Susan Dermodyn and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia: Anatomy of a Film Industry, Vol. 2, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988.

Peter Fitzpatrick, Williamson, Methuen, Sydney, 1987.

Gordon Glenn and Scott Murray, ‘Production Report: Don’s Party’, Cinema Papers, March-April, 1976.

Sandra Hall, Critical Business: The New Australian Cinema in Review, Rigby, Adelaide, 1985.

Peter Hamilton and Sue Mathews, American Dreams: Australian Movies, Currency Press, Sydney, 1986.

H.G. Kippax, ‘Preface to the First Edition’, Don’s Party, Currency Press, Sydney, 1973.

Brian McFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, Methuen/bfi publishing, London, 1977.

Brian McFarlane, Australian Cinema 1970-1985, Secker & Warburg, London, 1987.

Brian McFarlane and Geoff Mayer, The New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992.

Brian McFarlane, Geoff Mayer and Ina Bertrand (eds), The Oxford Companion to Australian Film, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 1999.

Peter Malone (ed.), Myth & Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency, Strawberry Hills, 2001.

Scott Murray (ed.), New Australian Cinema, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1980.

Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Film 1978-1994: A Survey of Theatrical Features, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1995.

Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London, 1996.

Tom O’Regan, ‘Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films’, in Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1989.

Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980 (revised edition 1998).

Jonathan Raymer, Contemporary Australian Cinema, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2000.

Eric Reade, History and Heartburn: The Saga of Australian Film 1896-1978, Harper and Row, Sydney, 1979.

David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1980.

David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990.

David Williamson, Don’s Party, Currency Press, Sydney, 1973.

Robin Wood, ‘Quo Vadis Bruce Beresford?’ in Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan (eds), An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Length: 90 minutes. Format: 35mm. PC: Double Head Productions. Producer: Phillip Adams. Director: Bruce Beresford. Screenplay: David Williamson, from his play. Original Music: Leos Janacek. Piano: John Grayling. Editing: William Anderson. Art Director: Rhoisin Harrison (set decorator). Titles: Fran Burke. Costume: Anna Senior. Sound: Desmond Bone, Graham Irwin. Sound Editor: Lyn Tunbridge. PH: Don McAlpine. Camera Operator: Gale Tattersall. Casting: Alison Barrett. First Assistant Director: Mike Martorana. Second Assistant Director: Toivo Lember. Continuity: Moya Iceton. Make-up/Hair: Judy Lovell

CAST

Don Henderson: John Hargreaves. Kath Henderson: Jeanie Drynan. Mal: Ray Barrett. Jenny: Pat Bishop. Mack: Graham Kennedy. Simon: Graeme Blundell. Jody: Veronica Lang. Cooley: Harold Hopkins. Susan: Clare Binney. Kerry: Candy Raymond. Evan: Kit Taylor. Himself: John Grey Gorton.

Endnotes

| 1 | Interview with David Williamson, March 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by DW). |

|---|---|

| 2 | Gordon Glenn and Scott Murray, ‘Production Report: Don’s Party’, Cinema Papers, March-April, 1976, p.339. |

| 3 | Interview with Wilfred Last, March 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by WL). |

| 4 | In Crashing the Party, a feature-length documentary accompanying the DVD of Don’s Party. |

| 5 | Graeme Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, Theatre Australia, Vol 1, No. 5 (1976–77), p.37. |

| 6 | John Clark, ‘Director’s Note’, in David Williamson, Don’s Party, Currency Press, Sydney, 1973, p.xi. |

| 7 | Ray Barrett, with Peter Corris, Ray Barrett: An Autobiography, Random House, Sydney, 1995, pp.181, 182. |

| 8 | H.G. Kippax, ‘Preface to the First Edition’, in ibid., p.x. |

| 9 | Peter Fitzpatrick, Williamson, Methuen, Sydney, 1987, pp.62–63. |

| 10 | Brian McFarlane, ‘Lee, Wilfred Jack Raymond’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition, 2006, <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/77340>. |

| 11 | ‘Jack Lee’, in Brian McFarlane (ed.), An Autobiography of British Cinema, Methuen/bfi publishing, London, 1997, pp.355–58. |

| 12 | Interview with Phillip Adams, February 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by PA) |

| 13 | Quoted in Glenn and Murray, op. cit., p.341. |

| 14 | Interview with Bruce Beresford, February 2007 (source of subsequent unattributed comments by BB). |

| 15 | Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1992, p.60. |

| 16 | John Pym, ‘Side by Side’, Monthly Film Bulletin, March 1976, p.63. |

| 17 | Quoted in Coleman, op. cit., p.61. |

| 18 | Quoted in Glenn and Murray, op. cit., p.342. |

| 19 | Coleman, op. cit., p.65. |

| 20 | See Barrett, op. cit., p.188. |

| 21 | Blundell, in Crashing the Party. |

| 22 | Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, op. cit., p.37. |

| 23 | Beresford in Crashing the Party. |

| 24 | ibid. |

| 25 | Harold Hopkins in ibid. |

| 26 | Graeme Blundell, King: The Life and Comedy of Graham Kennedy, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2003, p.324. |

| 27 | ibid. |

| 28 | Quoted in ibid, p.323. |

| 29 | British Television (compiled by Tise Vahigami), Oxford University Press, 1996, praised it for its ‘sharp and well-defined scripts [which] made this one of the more exciting mid-1960s drama series’, p.138. |

| 30 | Adams in Crashing the Party. |

| 31 | ‘Production Report’, Don’s Party, op. cit., p.339. |

| 32 | ‘Production Survey’, Cinema Papers, #10, September-October 1976, p.160. |

| 33 | David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, Sydney et al, 1980, p. 307. |

| 34 | ‘Don’s Party’ in Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980 (revised edition 1998), p.305. |

| 35 | Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia, Vol.1: Anatomy of a Film Industry, Currency Press, Sydney, 1987, p.224, 222. |

| 36 | Kippax, op. cit., p.vii. |

| 37 | Magnus Magnusson (ed.), ‘Greer, Germaine’, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, W & R Chambers, Ltd, Fifth Edition, Edinburgh, 1991, p.624. |

| 38 | Raymond Stanley, ‘Don’s Party’, Cinema Papers, Issue 11, January 1977, p.266. |

| 39 | Blundell, ‘Don’s Party … Then and Now’, op. cit., p.37. |

| 40 | See, for instance, David Stratton, op. cit.; Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, op. cit.; Brian McFarlane, Australian Cinema 1970-1985, Secker & Warburg, Ltd, London, 1987. |

| 41 | Sandra Hall, Critical Business: the New Australian Cinema in Review, Rigby Publishers, Adelaide et al, 1985, p.101. |

| 42 | Stratton, op. cit., p.120. |

| 43 | Bruce Beresford, ‘Don’s Party from Play to Film’, Theatre Australia, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1976-77, p.33. |

| 44 | Percy A. Scholes, The Oxford Companion to Music (1938), Oxford University Press, London, 1963, p.258. |

| 45 | William Shakespeare, King Lear, Act 3, Scene iv, l.96. |

| 46 | Stratton, op. cit., p.49. |

| 47 | Blundell, King, op. cit., p.326. |

| 48 | ‘News from Cannes’, Filmnews, June 1977, p.5. |

| 49 | ‘Territories Sold at Cannes’, Cinema Papers, Issue 13, July 1977, p.33. |

| 50 | For those interested in following up the overseas reviews, the Australian Film Institute library has a prolific cuttings file on the film (and on many others). |

| 51 | Judge Thomas Griesa, in the US District Court, New York, quoted in Brisbane Courier-Mail, 5 May 1987. |

| 52 | Stratton, op. cit., p.48. |

| 53 | Dermody and Jacka, op. cit., p.184. |

| 54 | Tim Pulleine, Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1979, p.22. |

| 55 | Eric Braun, Films and Filming, May 1979, p.37. |

| 56 | See AFI cuttings file on the film. Walker and The Financial Times critic were quoted in The Sunday Telegraph (Sydney), 22 April 1979; and Gibbs were reported in both The Herald (Melbourne), 21 April 1979 and The Canberra Times, 23 April 1979. |

| 57 | Hall, (reprinted in Critical Business, op. cit.), p.58. |

| 58 | Stanley, Cinema Papers, op. cit., p.266. |

| 59 | Geraldine Pascall, ‘Full frontal male ignominy’, The Australian, 6 December 1976. |

| 60 | Robin Wood, ‘Quo Vadis Bruce Beresford?’, in Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan, An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985, pp.200, 201, 202. |