Reprinted from Meanjin Quarterly Vol 36/No 4/December 1977 with the kind permission of the editor.

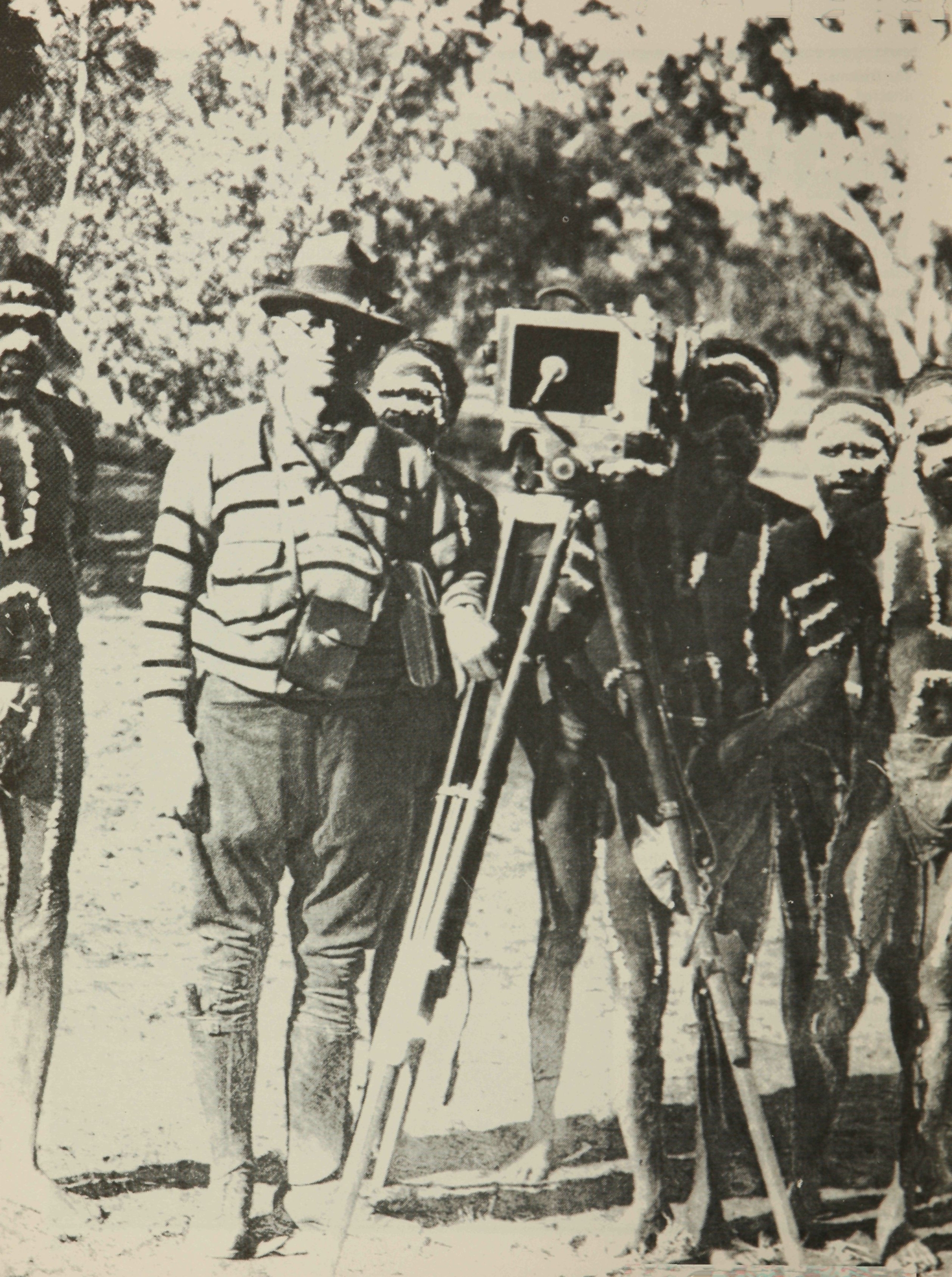

In non-narrative cinema – in ethnographic films especially – white Australians have been consciously documenting Aboriginal life and culture since the earliest days of the cinema. Baldwin Spencer was making pioneering ethnographic films as early as 1900, and the tradition continued through popular documentary adventurers and romantics such as Francis Birtles and Frank Hurley, to more serious work in the 1960s by Cecil Holmes, Ian Dunlop, Roger Sandall, and visiting anthropologists from the U.S.A. and elsewhere. But such films have generally aimed at a certain degree of objectivity, without overt political or moral biases, and it is not until we look at narrative cinema that we can more clearly see the range of values which white film-makers have attached to Aboriginal people.

Aboriginals are in fact absent from the majority of Australian feature films – even those set in the bush, such as the Hayseeds or the Dad and Dave series – and the absence reflects a lack of awareness and comprehension of Aboriginal existence that is perhaps common to most urban Australians, the very Australians who made most films. Even when Aboriginals did figure in movies, the parts were most commonly played by white actors in ‘blackface’, a practice which persisted as late as 1967 with Journey out of Darkness*, where the two principal Aboriginal roles were played by Ed Devereaux and Kamahl.

Aboriginals first appeared in Australian cinema in the bushranging genre which flourished in the first few years of the industry, until 1912. Early in that year such films were suppressed by the New South Wales police for fear that they would encourage disrespect for the law and glamorise anti-social behaviour. This state of affairs prevailed until the 1940s, by which time Australian audiences had lost their familiarity with bushranging folklore and the genre was no longer part of popular culture. One of the most recurring elements in it was the Aboriginal side-kick to the bushranging hero. Invariably played by a white actor in blackface, the offsider was a faithful ally to the hero and stood by him in times of stress, often risking life to rescue him from the police. The dramatic highlight of Assigned to his Wife (1911), for example, was ‘The Dive for Life’, in which Yacka, the faithful friend of a convict escapee in the bush, leaps 250 feet from a cliff into a river to save the hero’s life. In the same film- the bond between Yacka and his white friend expressed a mutual commitment, for later when the hero is restored to his rightful place as master of an English stately home, he takes the Aboriginal boy back to England with him to serve on the estate. Other Aboriginal offsiders to bushranging heroes figure in Robbery Under Arms (1907), Dan Morgan (1911), and The Assigned Servant (1911). And although they were outlaws, none of the Aboriginals were necessarily villainous: usually the bushranger was a romanticised and heroic figure, even if he paid a heavy price at the end of the film, and his Aboriginal friend was always a worthy ally, displaying strong virtues of loyalty and reliability.

In a recent reprise of the bushranging theme, Mad Dog Morgan (1976), the Aboriginal ally reappeared, extended far beyond the formula requirements of the original genre. Here Morgan not only depends on Billy for his physical survival but also becomes emotionally dependent: Morgan’s only expression of love for another human is towards the young Aboriginal.

In comparison with other racial minorities in Australian films, Aboriginals were rarely the butt of explicit racism. Only one film, Caloola or the Adventures of a Jackeroo (1911), depicted a white man’s vendetta against Aboriginals, reflecting the readiness, which many white settlers had possessed, to shoot at Aboriginals on sight. Chinese (or Asians generally) fared much worse, and on several occasions were the subject of vigorous racist abuse by Australian film-makers. Raymond Longford’s Australia Calls (1913) expressed the Bulletin‘s xenophobia in a screenplay by two of the magazine’s regular contributors. C A . Jeffries and John Barr. In their story of an Asian invasion of Australia, and the rallying of Australian manpower to expel the yellow hordes, the Aboriginals were clearly on the side of the whites, and one comic scene showed an Aboriginal station hand enthusiastically beating up the Chinese cook as soon as war is declared. Again, in The Birth of White Australia (1928), directed by Phil K. Walsh, the threat against white supremacy in Australia came solely from Asians, and the Aboriginal was little more than a harmless comic character, over whom the white man was confidently in control.

Aboriginals have perhaps most commonly appeared in Australian films as figures in a landscape, as exotic and mysterious details bestowing local colour to outback dramas concerned exclusively with white problems. The Aboriginal corroboree especially has long been exploited as a novelty, from A Blue Gum Romance (1913), where the dance was performed by city boys in blackface, to perhaps the most spectacular of all corroboree ballets, choreographed by a white, in Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised* (1936). Corroborees often figured as a token sign of authenticity in films made in Australia for non-Australian audiences. Down Under (1927) was made by a Western Australian company for the British market and featured a corroboree as one of its main highlights, and in Kangaroo, produced by Twentieth Century Fox in 1952, scenes of Aboriginal dances behind the credits gave one of the few clues to the story’s Australian location. Aboriginal gum-leaf bands had a similar novelty function in The Squatter’s Daughter* (1933), where vividly painted Aboriginals in loin-cloths are featured at a fashionable society party, and in Rangle River (1936), a group of Aboriginals playing gum leaf music are noticed in a paddock by the hero (the American, Victor Jory) who cracks his whip at them and enjoys a hearty laugh as the Aboriginals scamper away. A display of boomerang-throwing was inserted in a similar, arbitrary way into The Kangaroo Kid, an American Western filmed on Australian locations in 1950. Another Western, made by Australians in 1953, The Phantom Stockman, presented Chips Rafferty as a legendary lone avenger of the law, known as the Sundowner. Like the Lone Ranger, he had a coloured side-kick, this time an Aboriginal, Henry Murdoch, in the role of the Australian Tonto. In this film, the Aboriginals are depicted as figures of mysterious power, and the Sundowner is dependent on his side-kick’s prowess in mental telepathy to defeat the white villains. A digression from the plot also introduces one of the Sundowner’s old friends, none other than Albert Namatjira, found painting one day in the desert: the film pauses for a brief interview. The film’s director, Lee Robinson, had not long before made a government documentary about Namatjira, and this arbitrary touch of local colour was a naive attempt to promote Namatjira commercially to the urban Australian public.

The exoticism and mystery of Aboriginal life has continued to draw film-makers, and in 1971 formed the basis of Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, where an Aboriginal youth (played by David Gulpilil) is a primitive heroic figure in a strange mythical land. In Storm Boy (1976), Gulpilil plays a similar role, a man close to the earth and in harmony with nature. In both films, Gulpilil emerges from white romantic ideals of ecology and the environment: he is not so much a noble innocent as an expression of natural energies, and a tragically lone reminder of the decay of nature and the loss of harmony in white civilisation.

The Last Wave (1977) exploits the traditional mystique inherent in many white views of Aboriginals, by making it the focus of a lawyer’s attempt to solve a murder mystery. As he unravels the enigmas of Aboriginal life, it becomes clear that understanding is not available to ordinary Australians: the lawyer himself has definite psychic powers and his other worldly connections are the key to his discovery of the secrets of Aboriginal dream-time. To some extent, the film balances mysticism with observation of harsh social realities in the life of urban Aboriginals in Sydney, but it ultimately evades these social issues by revealing in the final scenes that the basic premises of the plot are rooted in science fiction fantasy, with the discovery of the remains of a lost civilization and cave paintings which forecast a terrible holocaust for the city.

Until recently, the Aboriginal in film was generally too primitive, one must assume, to have close romantic involvement with white men or women, and Aboriginals did not figure at all in any local variant of the old Hollywood genre of inter-racial romance. The genre, which flourished during and after World War One, usually depicted the ill-fated and often unrequited love of a non-white man or woman for a white. Sessue Hayakawa played many such roles in Hollywood in the 1910s and 1920s, and there were dramatic antecedents in popular stage melodramas such as The Octoroon, a play by Dion Boucicault set in the Deep South of the U.S.A. which was filmed in Australia in 1911. A few films in the genre were made in Australia, and two depicted love affairs between whites and Maoris (A Maori Maid’s Love made by Raymond Longford in 1916, and Beaumont Smith’s The Betrayer in 1921), but white involvement with Aboriginals seems to have been scrupulously avoided, even when historical fact confronted Australian film-makers with the relationship of Captain Thunderbolt to his ‘half-caste’ mistress. In Thunderbolt (1910), the directors, John Gavin and Herbert Forsyth, cautiously referred in their synopsis to a half-caste girl who rescues Thunderbolt from the police. Later, in 1953, Cecil Holmes’ Captain Thunderbolt* was somewhat franker, with the relationship clearly evident, although it remained a subdued and sexless affair, closer perhaps to friendship than to romance.

Feature films focussing directly on Aboriginal characters began to emerge after World War Two, but none existed before the 1940s. Ken G. Hall, who directed sixteen features for Cinesound during the 1930s, once explained the almost complete absence of Aboriginals in his films by saying that he was unable to make them credible as villains for Australian audiences. Whenever Aboriginals did appear as villains in early Australian films, it was usually as thinly disguised substitutes for coloured people in formula plots deriving from other cultures, whether Indians in Westerns or African tribes in jungle adventures. Not surprisingly, many of these films were made by visiting American or British directors. Perhaps one of the most bizarre examples occurred in 1928 with The Romance of Runnimede* a ‘Great White Queen’ saga directed by a Hollywood specialist in B-grade Westerns, Scott Dunlap. In the film, a girl returns to her father’s outback station after an absence of many years in the city. The local Aboriginals take her to be the reincarnation of their ancient queen, and kidnap her. The Aboriginals are led by an evil witchdoctor, Goondai, played by a white actor, Dunstan Webb; Goondai and the tribe make absurd villains, dancing a corroboree that looks like a conga, and all of them dressed in knee-length grass skirts. The absurdity was probably immaterial to the film-makers, who had American audiences firmly in mind in constructing the film, with an American star, Eva Novak, as the white queen, and with introductory maps of Australia and Queensland to place the film geographically for their audience. In other genres of American pulp fiction, Aboriginals appeared in a local Tarzan movie (Charles Chauvel’s Uncivilised* in 1936), and provided slapstick comic relief in grotesque imitation of the flapper fashion in Trooper O’Brien* (1928). They also appeared several times as guardians of desert gold fields, in the spirit of the African tribesmen in the novels of Rider Haggard (The Kingdom of Twilight, made in 1929 by a Scottish director, Alexander Macdonald; The Tenth Straw, made in 1926; and in parody form in Strike Me Lucky, 1934).

The first narrative films expressing any degree of concern or sympathy for Aboriginals, in their actual position as an exploited racial minority in Australia, were made by Englishmen. Towards the end of World War Two, the British company of Ealing embarked on a series of feature films set in the countries of the British Commonwealth. The first studio for the programme was established in Sydney, and one of Ealing’s top directors, Harry Watt, arrived in 1944 to begin the two-year preparations for The Overlanders*. Like many Ealing directors, Watt was a socially and politically alert film-maker, and his liberalism was evident in The Overlanders in a short but impassioned speech by Chips Rafferty protesting against reckless white exploitation of the resources of the Northern Territory, and the consequent dislocation of the Aboriginal stockmen, with Clyde Combo and Henry Murdoch (both Aboriginals) playing the first of several screen roles as stockmen. Watt’s film unobtrusively expressed awe for the stockmen’s skill and for their authoritative knowledge of the bush, and gave them lines which indicated heroic stature beneath a veneer of laconic understatement. The film’s achievements arose directly from Watt’s documentary training in England: in the interests of accuracy, he could not fail but present Aboriginals as an integral part of outback life, and their presence is felt throughout the film.

Social concern emerged far more strongly in Bitter Springs* (1950), an Ealing production directed by Watt’s assistant on The Overlanders, Ralph Smart. Bitter Springs was constructed specifically to explore the problems of Aboriginal land rights and the dispossession of Aboriginals by white settlers. The story presents a white family who trek into the wilderness to open up new land and to establish their own station. The leader is Wally King (played by Chips Rafferty), a stubborn and intolerant man who has never considered Aboriginals as landowners. When King and his family reach their allotted site and pitch camp at the only waterhole, they find that a tribe of Aboriginals also depend on it for their survival. A violent struggle for ownership ensues, and only after the death of his son does King relent and recognise the Aboriginals’ claim in a hasty compromise. A lone trooper, played by Michael Pate, appears intermittently throughout the film to make passionate pleas for an understanding of the Aboriginals’ point of view and he eventually mediates in the dispute to restore peace. The final solution is a very unequal compromise: the film ends by showing the Aboriginals working happily on King’s station, and it is very clear who is the master. But despite the hypocrisy of its ending, the film is for the most part imbued with genuine concern for the plight of the Aboriginals, and the white settlers are far from sympathetic characters.

Although Bitter Springs failed to fulfil its promise as an honest appraisal of the Aboriginal in Australian society, it was the first feature film to appear in which some of the central characters were Aboriginal and in which the story related directly to Aboriginal concerns. Its commercial failure was due more to its dramatic uncertainties than to its basic subject, and Aboriginals soon emerged again as the central focus of another feature. Jedda* (1955), directed by Charles Chauvel. Jedda neatly expresses one of the many dilemmas of white liberalism in facing the Aboriginal in contemporary society. The first half of the film, depicting the emotional development of an Aboriginal girl adopted by a white family, involves much discussion of whether it is counter-productive or humanitarian to force Aboriginals, against their ‘nature’, to adopt white ways. For although Jedda is raised in seclusion from other Aboriginals, her white foster-parents cannot deny her right and her will to explore her own heritage as an Aboriginal: she falls under the spell of a mysterious Aboriginal on the station, and becomes his half-willing, half-terrified kidnap victim. The ultimate resolution of the crisis, after a long chase through the desert, is Jedda’s death: a tragic ending that was far more pessimistic about Aboriginal relations with white society than Chauvel was probably prepared to admit either to himself or to his public. In many of his films, Chauvel attempted to present consciously Australian subjects in familiar Hollywood formats, and the film’s arguments are marred slightly by the conventions of Hollywood romantic melodrama. It remains, nonetheless, a landmark in Australian cinema, by confronting the white cinema audience forcefully with Aboriginals who are characterized as people with emotions and individual personalities.

After the completion of Jedda in 1955, feature film production in Australia ground to an almost complete halt until the revival around 1970 stimulated by government investment and subsidy. 35mm feature films intended to wide theatrical release tended to follow established patterns, and continued to avoid any emphasis on the politically delicate subject of Aboriginals except in minor roles. However, a far more stimulating wave of 16mm production gave rise to a number of films which made few concessions to the commercial market and had greater freedom to explore political and social issues. Two ‘mini’ features in this 16mm undergrowth stand out especially as portraits of Aboriginals in close contact with the white society of the 1970s. Come Out Fighting* (1973), directed by Nigel Buesst, was the first Australian film to present an Aboriginal in an urban environment (apart from incidental characters in scattered films like The Enemy Within*, 1917). Based on a play by Harry Martin, Come Out Fighting was a forceful and sympathetic study of a crisis in the life of an Aboriginal boxer (played by Michael Karpaney), who is under severe emotional pressure from many quarters – from his Aboriginal friends in the city, the boxing promoters, and a group of students campaigning for Aboriginal rights. The students want him to become a symbol for their cause, but at the same time he realises that success in a white world will risk the loss of contact with his own people. His final reaction to the dilemma is bleak: he rejects all of the demands made upon him and submissively allows himself to drift away from his one chance to achieve goals coveted by white society.

The second film, Backroads (1977), was the first in which an Aboriginal played a significant creative role in the production of a feature-length narrative film. The 16mm production was directed by Phil Noyce in close collaboration with the Aboriginal activist, Gary Foley. The story, constructed in the style of a ‘road’ movie, depicted the journey of an Aboriginal (played by Foley himself) and a white man (played by Bill Hunter) through a cross-section of the life and experiences of Aboriginals in contemporary Australia. The film reflected the new political awareness of Aboriginals and of some sections of the white community, and the result was an aggressive and bitter expression of despair.

Minorities of most types, whether racial, social or political, have rarely received more than peripheral attention from the commercial mainstream of Australian cinema, which has always been the domain of the white urban middle class. But the accessibility of film as a medium in the 1970s has suddenly made many of these minorities articulate in the cinema, and a duality has emerged: complacent features like Eliza Fraser appear in the established industry, while urgent films like Backroads are beginning to flourish outside. In the past, changes in the depiction of Aboriginals in Australian film were slow to take place: it took sixty years for black consciousness to eradicate the traditional ploy of blackface actors, and for Aboriginals to no longer appear as Indians or Africans. Films of social concern are no longer as isolated as they were in the 1950s, and they are able now to be far more outspoken because of the feasibility of low-budget productions free of the worst excesses of commercial compromise. Although Aboriginals have yet to direct their own feature films, the closer involvement of people like Gary Foley is beginning to accelerate the disappearance of the old stereotypes and see the emergence of a new, more direct representation of Aboriginals in film.

Note: film titles marked with an asterisk are held in the lending collection of the National Library of Australia, Canberra. Many of the other titles are also held in the National Film Archive but are not available for loan.

This article was written before the release of The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith.