There have been several times in my life when I was afraid to sit inside a darkened theatre during the projection of a film. The first was in 1994, when I went to a large commercial cinema in Melbourne to see Oliver Stone’s action-thriller-satire Natural Born Killers (1994). Even though the movie had barely started its local season – and these were still pre–peak Internet days – a bunch of guys up the back of the room continuously ran about, yelling Quentin Tarantino’s dialogue[1]While Tarantino’s screenplay for Natural Born Killers was substantially rewritten by Stone, David Veloz and Richard Rutowski – leading him to renounce his screenwriting credit – most of the dialogue in the film was retained from his original text. See Ryan Lattanzio, ‘Quentin Tarantino Has Never Seen All of Oliver Stone’s Version of His Natural Born Killers’, IndieWire, 1 August 2021, <https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/quentin-tarantino-oliver-stone-natural-born-killers-1234654847/>, accessed 8 January 2023. (which they had clearly already memorised) in time with the action and generally whooping it up. I was truly scared by the idea that, at some violent moment cued by the film (and there are many such moments), these fans would whip out guns from inside their bomber jackets and start firing into the crowd. Mercifully, they did not.

The second time was nine years later in Buenos Aires, Argentina, at a screening I myself had programmed as part of an Australian retrospective. It was Michael Lee’s experimental classic The Mystical Rose (1976). Whoever set the date of this event either had a wicked sense of humour or innocently presumed that it was a reverent, spiritually inclined work – because the day happened to be central in the religious calendar of that deeply Catholic country.

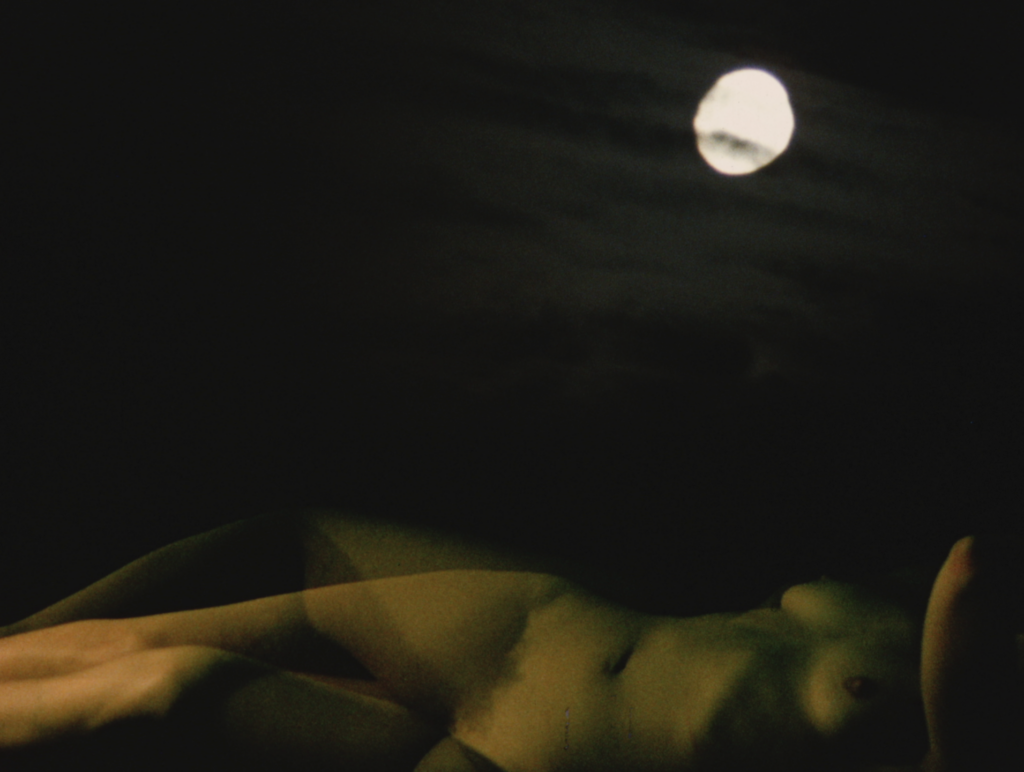

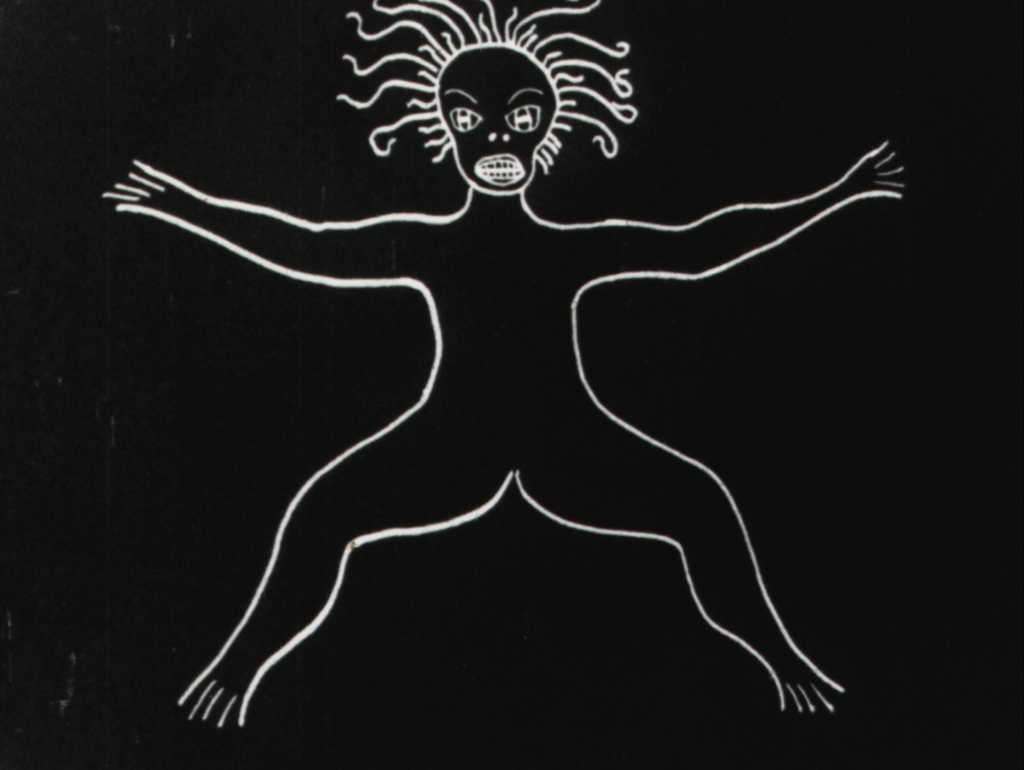

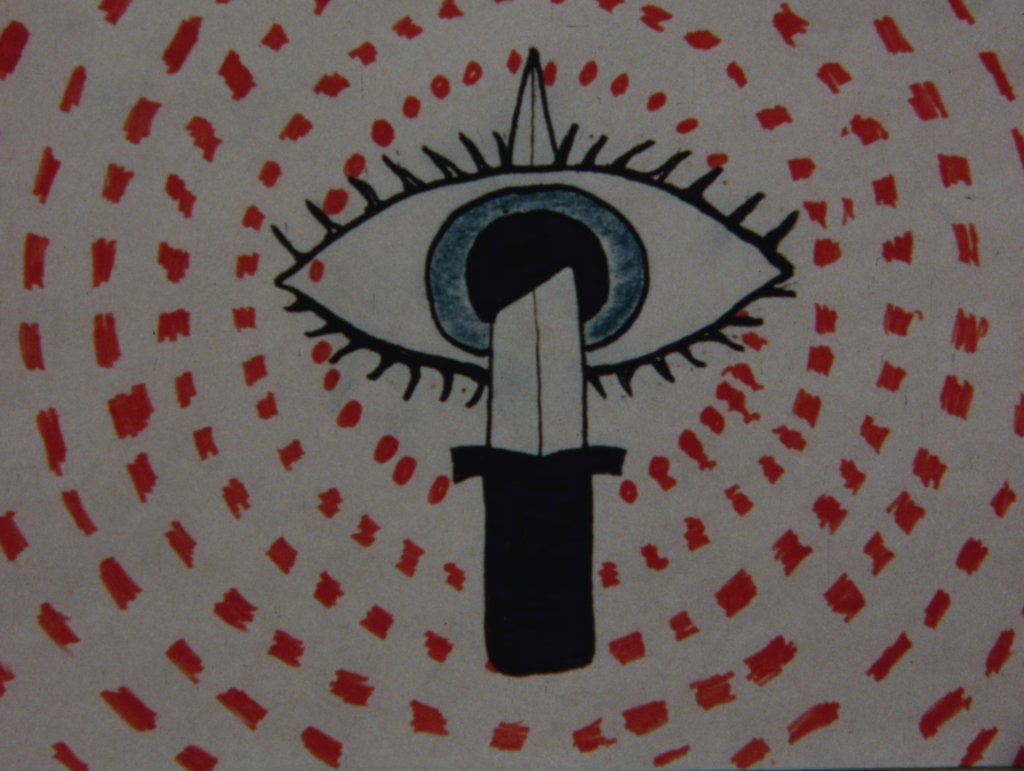

So, very quickly, this audience realised en masse that The Mystical Rose was an all-out assault on their most cherished belief system. A painted image of the Madonna holding the baby Jesus metamorphosed, via clever animation, into an androgynous figure kissing a giant penis – and then this tableau transformed, yet again, into a painting of Mary holding the recently crucified body of the adult Christ. On the soundtrack, solemn Gregorian chants were brutally interrupted by raucous rock’n’roll standards with suspiciously mock-religious titles like ‘Gloria’ and ‘Donna’. Live photographic images of erect men and writhing women were superimposed on lush natural landscapes; blossoming flowers proudly echoed female genitalia. Even the minimal, iconic form of the cross became, once animated, a depiction, radiating with heavenly light, of a penis moving inside a vagina. Oh mercy!

The crowd was, to say the least, not pleased, and they were making their reactions known in the dark. As I scrunched further and further down in my seat – and my translator spluttered, ‘Why on earth did you pick this for today?’ – I wondered whether I was going to get out of that cinema without getting lynched by an army of the devout. I have mostly erased from my memory the extremely tense, uncomfortable, post-film public discussion that ensued, which we tried to wrap up as quickly as possible. All I recall is that my erudite references to surrealist art, the psychedelic counterculture and the ‘cinema of transgression’ did nothing to stop the stream of angry verbal abuse from these paying customers. Curatorial lesson: The Mystical Rose, whatever its many virtues, is not a good Easter film.

Or, in another context, it could be the perfect Easter film! It is easy – too easy – to label The Mystical Rose as a ‘product of its time’, as if to politely imply that it has no further possible resonance today. Handcrafted over several years, completed in 1976 and publicly premiered in 1977, The Mystical Rose still preserves its energy and packs its punch (as I discovered in Buenos Aires). Iconoclasm, of the type Lee practiced, will always find a new time and place in which it is felt to be relevant and necessary. In this sense, the film could be thought of as a punk gesture just before its time – and we all know that the anarchic, young spirit of punk, across all the arts, never really dies.[2]For a delightful reflection on the eternal significance of punk, see Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1989.

Can The Mystical Rose rightly be called a ‘cult classic’ of Australian cinema? It should be, and probably could be, if more people were able to view it.

Can The Mystical Rose rightly be called a ‘cult classic’ of Australian cinema? It should be, and probably could be, if more people were able to view it. There is no VHS, DVD or Blu-ray edition available to buy (partly due to copyright restrictions that will be mentioned below), and the only access to it now is through the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Lee maintains a useful YouTube channel showcasing his film work – but, for whatever reason, The Mystical Rose is not included there.[3]Michael Lee YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/@MichaelLee-hd8fz>, accessed 8 January 2024.

An unusual hybrid

Let’s back up a little. What kind of film, exactly, is The Mystical Rose? An experimental film, surely – and one that benefited, in its day, from an unofficial ‘alternative’ circuit of exhibition that included the Melbourne Filmmakers Co-Op in Carlton and screenings at tertiary institutions such as Melbourne State College (a site for training teachers, since absorbed into the University of Melbourne), where Arthur Cantrill’s classes on avant-garde film history were open to anybody interested, and to which filmmakers were often invited. It was in this tertiary education setting that I first experienced Lee’s work and met the director himself.

By the late 1970s, Lee had already started to distance himself somewhat from the excesses of both filmmaking and general lifestyle exhibited in The Mystical Rose. The director’s philosophical and spiritual evolution had, by then, taken him elsewhere, into a less outrageous form of expression. Around a decade later, when small arts organisation the Modern Image Makers Association (known today as Experimenta Media Art) screened a retrospective of his work, his equally remarkable A Contemplation of the Cross (1989) showed how the artist had come to identify almost totally with the figure of Christ.

With a running time of sixty-five minutes, The Mystical Rose occupies a peculiar position between feature-length narratives and the (frequently) shorter works of the Australian avant-garde. In its era, it was quickly perceived as an unusual hybrid of many practices and forms: it’s not abstract, like some work of the Cantrills; not a documentary essay, like the political cinema of John Hughes; and not a rigorously formal ‘structural’ piece, like Lynsey Martin’s output, and as some of Lee’s earlier shorts had more or less been. The Mystical Rose is clearly a very personal outpouring of curiosity and angst, but not presented in an overtly intimate or diaristic way (in the manner deployed, for instance, in the then-burgeoning feminist filmmaking scene).[4]For a good documentation of this period, see Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed & Freda Freiberg (eds), Don’t Shoot Darling! Women’s Independent Filmmaking in Australia, Greenhouse Publications, Melbourne, 1987.

At the time it emerged, The Mystical Rose was very evidently a sort of pop art event, drawing upon various strands of popular culture. Appropriated pop music (by artists such as Pink Floyd, Them, Gary Glitter and John Lennon) fills the soundtrack – and inadvertently fixed the film’s future destiny as an effectively undistributable work under our present copyright regime. Numerous images of heavily stereotypical beauty and glamour are snipped by Lee from mass-circulation magazines. We are not far here from the work of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein or other celebrated pop artists of the 1960s and well beyond, such as Keith Haring in the 1980s.

Another kind of affinity with the gallery/museum art world is the presence of so-called high culture in the film – usually for the purposes of subversion, but sometimes with an elevated, sublime effect. Classical paintings used include Rogier van der Weyden’s Virgin and Child, while a short, instrumental sequence of four chords from Erik Satie’s Socrate is looped with particular expressive force.

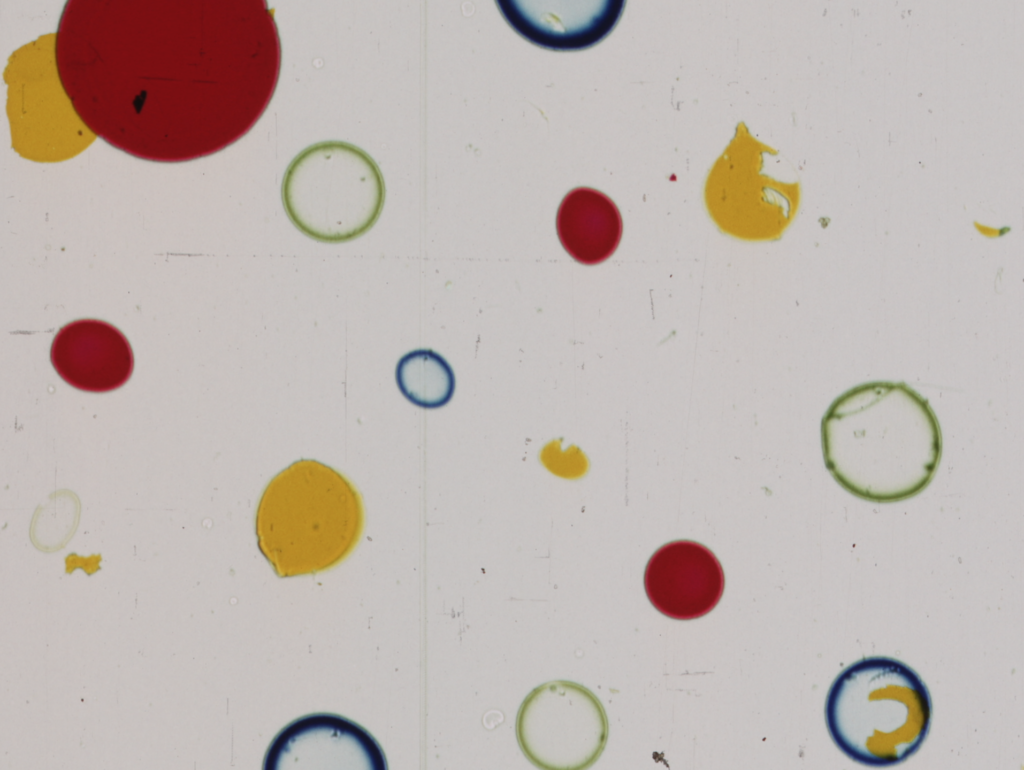

I would describe The Mystical Rose as, above all, a collage film. Many of its images are mobile collages of cut-up pictorial fragments. More substantially, the film, taken as a whole, is a large-scale collage of sequences arranged in large blocks, their order and arrangement continually shuffled. Indeed, The Mystical Rose is a rare and historically important demonstration of the precise crossover between collage in the art-world sense and montage in the cinematic sense.[5]I have devoted two essays to the relation between collage and montage in Australian audiovisual work: Adrian Martin, ‘The Cutting Edge: Collage and Montage in Australian Experimental Film and Video’, republication forthcoming in Art + Australia, 2024 [1989]; and Martin, ‘Something Close to Nothing: Appropriation in Australian Experimental Film and Video of the 1980s’, in Rex Butler (ed.), What is Appropriation?: An Anthology of Critical Writings on Australian Art in the ’80s and ’90s, Institute of Modern Power, Brisbane, 1996. Its unfolding structure can be studied deeply in this light.

Anti-cinema?

In 1980, I gave a lecture (one of my first ever) to an audience comprised of members of the Association of Teachers of Media.[6]Today known as Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM), the publisher of the article you are now reading. I still possess the detailed notes I prepared for it. It was about how to use the tools of semiotic ‘textual analysis’ – all the rage in the pedagogical context of the time – on Australian cinema. My demonstration pitted the ‘classical narrative mainstream’ example of Peter Weir’s already canonised Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) against the decidedly non-mainstream The Mystical Rose – a double bill never to be repeated, at least as far as I’m aware!

The entire film is a churning cluster of key, veritably iconic images that are constantly transformed – alchemically, one might say – through being literally animated.

To orient my listeners, I began by paraphrasing the definition of experimental/avant-garde cinema then offered in the official media studies curriculum for secondary school use in Australia: as distinct from the wider field of independent filmmaking, the avant-garde deliberately leans to the side of ‘displeasure and provocation’.[7]Adrian Martin, lecture delivered to the Association of Teachers of Media, Melbourne, 5 June 1980. The Mystical Rose sets out, I argued, to upset the standard contract between spectator and film. In comparison to Picnic at Hanging Rock – a superbly crafted film full of elegant, neatly structured, subtle rhymes and echoes on all micro and macro levels of story and style – I suggested to my 1980 audience that Lee’s opus is devoted not to smoothness or fictional illusion but to a raw reflexivity, displaying all its many techniques on the surface. Or, to use the lingo of the time, it celebrates a raucous heterogeneity rather than streamlined homogeneity.

Moreover, I proposed that The Mystical Rose courts a heady sensation of waste, confusion, incoherence – or what the radical philosopher Jean-François Lyotard had dubbed in 1973 as ‘acinema’, an anti- or non-cinema.[8]For a comprehensive treatment of this theme, including a new translation of Lyotard’s ‘Acinema’ essay itself, see Graham Jones & Ashley Woodward (eds), Acinemas: Lyotard’s Philosophy of Film, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2017. Today I see the matter rather differently, and through a less polemical frame. Lee’s film is indeed very pleasurable (to me, at least), and it possesses a definite coherence. However, that coherence is of a poetic, rather than narrative or essayistic, nature. The entire film is a churning cluster of key, veritably iconic images (rose, cross, lamb, vagina, penis, mountain, etc.) that are constantly transformed – alchemically, one might say – through being literally animated. Jake Wilson has described this process well:

The desire pent up by Catholicism breaks free in a barely controlled stream of images, as if the very principle of metaphor had been uncovered for the first time and seized upon as a key that might unlock the world.[9]Jake Wilson, ‘The Mousoulis Vision of Independence’, Realtime, no. 63, October–November 2004, <https://www.realtimearts.net/article.php?id=7575>, accessed 7 January 2024.

If The Mystical Rose is acinema, then recall that, for Lyotard, acinema is not only the site of anti-capitalist wastage, but also the locus of psychic drives and rich metamorphoses of signification – accompanied, in Lee’s case, by an often very black humour.

Other contexts

There are several contexts, beginning both before and after the film’s initial moment, in which The Mystical Rose can be productively placed. I have come, in recent years, to closely relate it to a certain mystical and psychedelic tradition of trance or ‘trip’ films of which Lee may have been only partly aware in the mid 1970s. The work of Alejandro Jodorowsky and of Sergei Parajanov, Philippe Garrel’s The Inner Scar (1972), and Dennis Hopper’s way-out The Last Movie (1971) now enjoy greater distribution on DVD or Blu-ray than Lee’s masterpiece is ever likely to achieve. Despite this, I would argue, the films form a family.

All of these works boast mythopoetic forms and structures. Just as The Inner Scar, per the film’s co-star Pierre Clémenti, illustrated the successive paths of alchemy as described in ancient, sacred texts,[10]Olivier-René Veillon, ‘Entretien avec Pierre Clémenti’, Cinématographe, no. 61, October 1980, p. 37. The Mystical Rose adopts the form of the Catholic Mass: the introductory rites, the Liturgy of the Word, the Liturgy of the Eucharist and the concluding rites.[11]See Dirk de Bruyn, ‘Re-processing The Mystical Rose’, Animation Studies, vol. 11, 30 December 2016, <https://journal.animationstudies.org/dirk-de-bruyn-re-processing-the-mystical-rose/>, accessed 8 January 2024. Yet, in both cases, such a template, even if consciously used at the outset of creating the work, only loosely fits the final, edited result. There is too much swirling repetition of elements, too intense and complex a flow of contradictory drives in The Mystical Rose for this ritual schema to hold from start to end.

In his retrospective essay on the film, Dutch-Australian filmmaker and scholar Dirk de Bruyn chooses to view The Mystical Rose within a specific lineage of animation cinema, a history marked by the names of Jan Švankmajer, Harry Smith, Walerian Borowczyk and Peter Foldes, along with – once again from the sphere of pop culture – Terry Gilliam’s contributions to the cult TV series Monty Python’s Flying Circus.[12]ibid. This is itself a provocative classification of the work, since Lee’s collage method is by no means restricted to a panoply of frame-by-frame animation techniques – it also contains slow-motion live photography of street scenes and ‘found footage’ (mainly derived from the 1925 Buster Keaton comedy Go West) crisply edited into the flow of disparate materials. De Bruyn’s point, however, is crucial: Lee was not only channelling an alternative, non-Disney history of animation, but also anticipating an expanded form of it that would become popular decades later – for instance, in fact-based ‘animated documentaries’ such as Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008).[13]See Alice Burgin, ‘Guilt, History and Memory: Another Perspective on Waltz with Bashir’, Metro, no. 164, 2010, pp. 70–4.

The hybrid, collage nature of The Mystical Rose lends itself – increasingly so, as time goes by – to such across-the-board mappings, networkings and extrapolations.

The bachelor machine

Of all the autonomous sequences in The Mystical Rose, one has most vividly stuck in my brain – from the very first screening I saw to the most recent. It is a scene that presents, and then animates, an odd, surreal, miniature sculptural assemblage of Lee’s making. There is a sort of penis-bird (fashioned from bits of wood) that spins a wheel, which, in turn, moves a string. Along this string, a fluffy cloud shifts from right to left of screen, and a lightbulb is lifted. But then, as if the load is too heavy, the wheel spins in the opposite direction and the objects fly back to their original position. And off we go again …In a truly inspired bit of audiovisual linkage, Lee places over the image a maddening, looped fragment of the unlikely 1968 pop hit ‘Merry-Go-Round’ (performed by Wild Man Fischer and produced by Frank Zappa).

One could see this cinematic spectacle as the nth illustration of the existentialist myth of Sisyphus, but it reminds me, above all, of conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp’s sculptural work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (aka The Large Glass), made between 1915 and 1923. In preparation for the piece, Duchamp formulated in 1913 the idea of a ‘bachelor machine’ – referring to the eight shadowy gentlemen depicted in the lower half of the finished work, seemingly connected to a bunch of strange, technological devices. In the commentary offered by contemporary architect Christian Hubert,

The Large glass [sic] consists of two distinct realms, the realm of the bride above, and the realm of the bachelors below, both desiring and imagining one another without any possibility of mutual comprehension.[14]Christian Hubert, ‘Bachelor Machine’, Christian Hubert Studio website, 14 August 2019, <https://www.christianhubert.com/writing/bachelor-machine>, accessed 8 January 2024. Emphasis in original.

So there is, on an imaginary plane, much frantic, even pathetic movement on the part of the hopeful bachelors, but no ultimate union, let alone consummation with the bride – a little like the allegory we see in this sequence of The Mystical Rose.

Some will undoubtedly argue in 2023 that the explicitly sexual iconography of The Mystical Rose – and, indeed, its general sexual politics – has not aged well. So much thrusting genitalia; such idealisation of explosive, cosmic orgasm! And what about all that anxious castration imagery? Yet there’s a leitmotif of androgynous representation, an equality in the depiction of genders (female and male bodies are equally laid bare for the camera – with the intimate quality, characteristic of avant-garde cinema, of those bodies belonging to the filmmaker and those closest to him) and an ironic, melancholic, defeated aura grafted onto the carnal, erotic realm. These aspects have to be duly taken into account. To be either a bachelor machine or a bride, it seems, ain’t much fun.

In another, stunning sequence – so good that Lee reprises it immediately – a montage-parade of penises, hammers and giant bird beaks all rock along in perfect synchronisation to the thumping beat of Gary Glitter’s camp cover of ‘Donna’. In any audiovisual anthology of the greatest hits of Australian cinema, that surely needs to be included.

Endnotes

| 1 | While Tarantino’s screenplay for Natural Born Killers was substantially rewritten by Stone, David Veloz and Richard Rutowski – leading him to renounce his screenwriting credit – most of the dialogue in the film was retained from his original text. See Ryan Lattanzio, ‘Quentin Tarantino Has Never Seen All of Oliver Stone’s Version of His Natural Born Killers’, IndieWire, 1 August 2021, <https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/quentin-tarantino-oliver-stone-natural-born-killers-1234654847/>, accessed 8 January 2023. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For a delightful reflection on the eternal significance of punk, see Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1989. |

| 3 | Michael Lee YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/@MichaelLee-hd8fz>, accessed 8 January 2024. |

| 4 | For a good documentation of this period, see Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed & Freda Freiberg (eds), Don’t Shoot Darling! Women’s Independent Filmmaking in Australia, Greenhouse Publications, Melbourne, 1987. |

| 5 | I have devoted two essays to the relation between collage and montage in Australian audiovisual work: Adrian Martin, ‘The Cutting Edge: Collage and Montage in Australian Experimental Film and Video’, republication forthcoming in Art + Australia, 2024 [1989]; and Martin, ‘Something Close to Nothing: Appropriation in Australian Experimental Film and Video of the 1980s’, in Rex Butler (ed.), What is Appropriation?: An Anthology of Critical Writings on Australian Art in the ’80s and ’90s, Institute of Modern Power, Brisbane, 1996. |

| 6 | Today known as Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM), the publisher of the article you are now reading. |

| 7 | Adrian Martin, lecture delivered to the Association of Teachers of Media, Melbourne, 5 June 1980. |

| 8 | For a comprehensive treatment of this theme, including a new translation of Lyotard’s ‘Acinema’ essay itself, see Graham Jones & Ashley Woodward (eds), Acinemas: Lyotard’s Philosophy of Film, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2017. |

| 9 | Jake Wilson, ‘The Mousoulis Vision of Independence’, Realtime, no. 63, October–November 2004, <https://www.realtimearts.net/article.php?id=7575>, accessed 7 January 2024. |

| 10 | Olivier-René Veillon, ‘Entretien avec Pierre Clémenti’, Cinématographe, no. 61, October 1980, p. 37. |

| 11 | See Dirk de Bruyn, ‘Re-processing The Mystical Rose’, Animation Studies, vol. 11, 30 December 2016, <https://journal.animationstudies.org/dirk-de-bruyn-re-processing-the-mystical-rose/>, accessed 8 January 2024. |

| 12 | ibid. |

| 13 | See Alice Burgin, ‘Guilt, History and Memory: Another Perspective on Waltz with Bashir’, Metro, no. 164, 2010, pp. 70–4. |

| 14 | Christian Hubert, ‘Bachelor Machine’, Christian Hubert Studio website, 14 August 2019, <https://www.christianhubert.com/writing/bachelor-machine>, accessed 8 January 2024. Emphasis in original. |