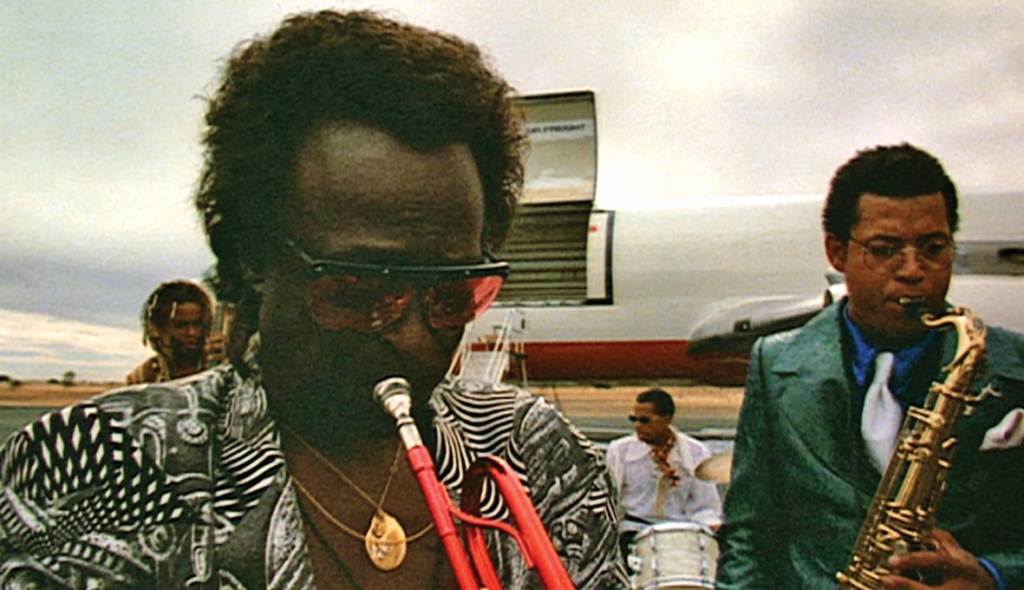

On a hot February day in 1969, twelve-year-old John Anderson (Daniel Scott) has destiny fall on him from the sky, so to speak: his sleepy outback town is rocked by a diverted jumbo jet as it thunders at low altitude above them to land at a nearby airstrip. Aboard the plane is internationally acclaimed jazz maestro Billy Cross (Miles Davis), who, as he emerges in the middle of the desert, is greeted by the understandably confused stares of the town’s population; in response, he fires up his band for an impromptu show. Watching the performance unfold, John is entranced, and a lifelong obsession with music is born – along with a quest to some day journey to Paris and play with his idol.

Dingo (1991), Rolf de Heer’s third feature, exists as part of a grand tradition established by classics such as A Star Is Born (George Cukor, 1954) and The Helen Morgan Story (Michael Curtiz, 1957): narratives of aspiring daydreamers chasing the romantic ideal of a life in music, and of the pitfalls that may potentially arise along the way. Yet Dingo takes a far humbler tack than these Hollywood rise-and-fall tales, with the film – in contrast with the director’s more renowned follow-up, the notoriously twisted urban fantasy Bad Boy Bubby (1993) – providing an early showcase of the gentler, more down-to-earth eye that would later become one of de Heer’s defining signatures as a filmmaker.

Dingo exists as part of a grand tradition: narratives of aspiring daydreamers chasing the romantic ideal of a life in music, and of the pitfalls that may potentially arise along the way.

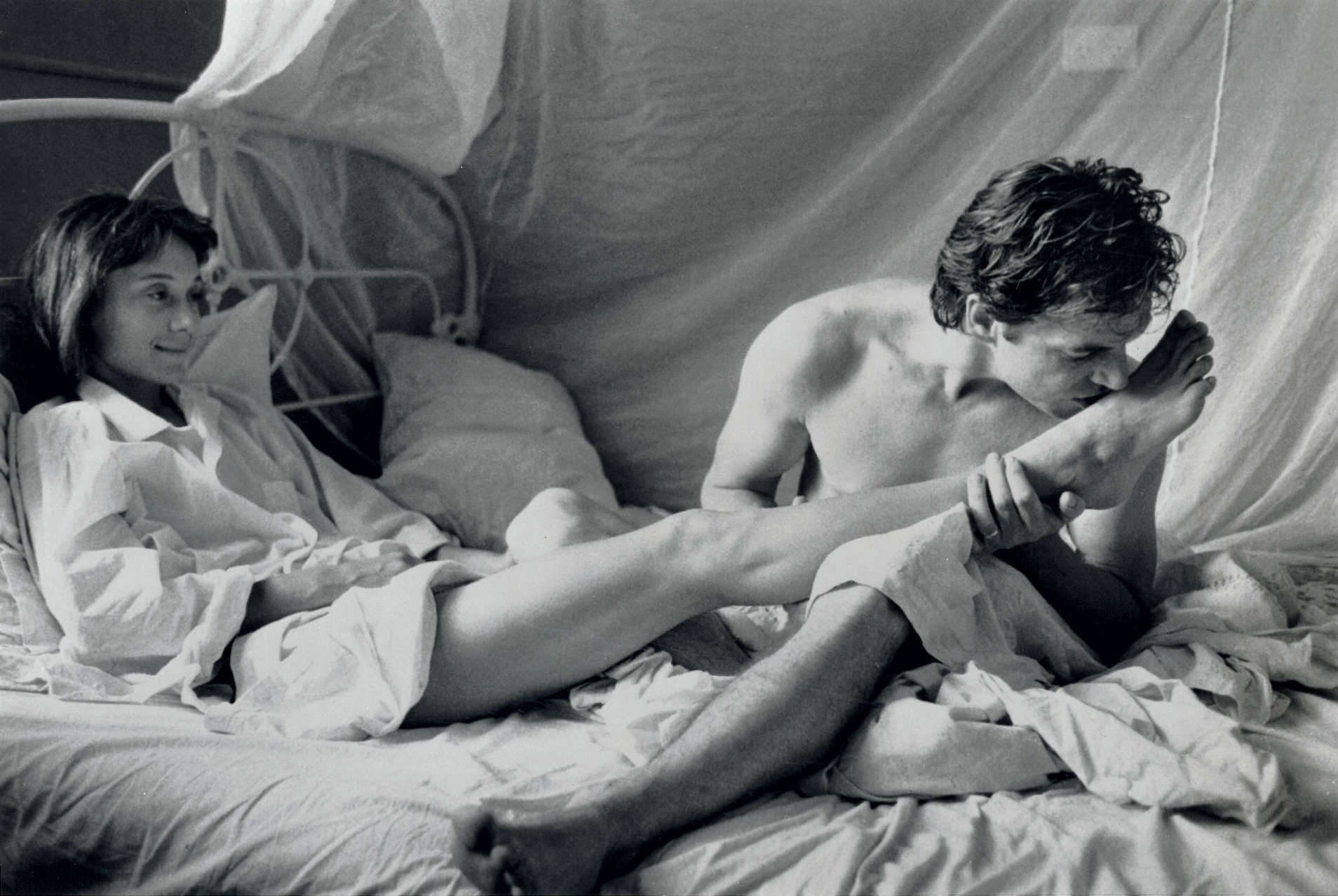

After the dreamy romanticism of the opening, the film settles into its story proper years later. An adult John (Colin Friels) – nicknamed ‘Dingo’ after his trade as a dingo trapper – now plays in a local pub band, having taken up the trumpet to emulate his hero, with whom he has maintained contact via endless fan letters. He has also gotten married and started a family with his childhood friend Jane (Helen Buday). Yet, despite this happy and settled life, he still dreams of Paris and a career in music.

This peace is disturbed by the return of Peter (Joe Petruzzi), a one-time best mate of John – and somewhat apathetic former boyfriend of Jane – who moved to Perth years ago to find success selling boats. It quickly transpires that the recently separated Peter has rekindled his romantic interest in Jane, ultimately threatening not just John’s long-term goals but also his current life. Jane tolerates John’s musical ambitions, but clearly loves him more as a man than an artist – a dynamic that immediately implies a possible gap in her needs that Peter may capitalise on.

While John is portrayed as being generally comfortable in his domestic life, Peter’s return exacerbates the friction points between his artistic ambitions and the responsibilities of maturity and interpersonal relationships. At first, Peter treats John’s passion for music with an amused scepticism: ‘You’re a dreamer; you always were,’ he tells him shortly after their reunion. However, Peter’s attitude quickly takes a more offensive turn. In attendance at a band practice, he sticks a finger in his ear to block out the sound of John’s trumpet so as to divert his entire attention to his conversation with Jane. This pointedly unsubtle gesture is not just a rejection of John’s musical talent but an implied usurpation of his status as her husband – one that, John is soon to learn, Peter threatens to enact in physical terms.

Ironically, Peter is just as ambitious as John, only in a very different direction. Peter’s goals are of the material kind, leading him to abandon his roots and seek his fortune in the big city. While this has brought some financial success, it ultimately appears to have done so at the cost of emotional grounding; having chosen the practical mechanics of the world, he now chases the dream he rejected in Jane. While John wears his heart on his sleeve, displaying his dreams to the world with boyish enthusiasm and an occasionally disarming openness, Peter, the self-styled man of the world, chases Jane in ways the practical world often rewards: with subterfuge and deceit, making an overt play for her while John is in Paris despite his earlier promises to the contrary.

While John is clearly loved by those around him, he also displays a lack of maturity, with his passionate, open nature at times exploding in a fiery temper. Embarrassed by Peter’s gesture during the practice, he compensates by berating the rest of the band and storming off stage. He’s later repaid for this outburst when the band members fake a letter from a music-publishing company telling him that they want to buy one of his compositions. By the time they can confess to the joke, John has already gone on a spending spree, assuming the costs will be covered by the non-existent publishing cheque.

John’s temper causes problems in his marriage, too. When Peter sneakily tells Jane about the secret stash of money John has been putting aside for a trip to Paris – money that is very much needed for domestic expenses – John, in another flash of immaturity, reacts angrily to both of them, creating a rift between him and Jane (as Peter has clearly planned). John’s passion may be a defining feature of his character, but in order for him to grow in the ways he needs to, it must be tempered.

The film’s narrative is framed around three dingoes. The first of these is ‘Dingo’ the man; while the second, most literal one is the livestock-menacing dog that John spends the first half of the film fruitlessly chasing. He describes it as ‘educated’: crippled after surviving one of his previous traps, the dingo has learned how to recognise where the traps are buried and neutralise them by dropping stones. On a superficial level, the dog acts as John’s second nemesis, disrupting his professional life just as Peter is putting his personal life in jeopardy. The dingo is also a pretty direct metaphor for John’s dreams – an inescapable constant that he can never conquer nor escape, and that, if left running wild for too much longer, will threaten his future.

However, the dog eventually reveals what may be its true purpose. When John, having hit his lowest point, finally gets the animal in his sights, we see the dingo turn into a vision of Billy’s band on the airport runway. One of the band members waves, beckoning him. It’s unclear whether the dog is some kind of spirit guide conjuring the vision, or whether this is all purely in John’s brain, but the result is clear: when he snaps back to reality, the dog has gone, and John has finally made the decision to go to Paris and meet his dreams head-on.

To do so, he must encounter the film’s third dingo – John’s hero, Billy. At first, the reunion is clearly not what John anticipated: Billy has become a very different man from the one he met all those years ago on the runway; following a stroke and becoming disillusioned with his career, he has spent years in self-imposed exile from the jazz scene, holed up in a home full of medical equipment and synthesisers on which he composes experimental music. Though he takes John out on the town – culminating in a visit to a jazz club, where he finally gives this odd, wide-eyed Australian dog trapper the horn duet he’s dreamed of for all these years – there’s an air of amused curiosity mixed with genuine concern surrounding him. Billy’s first words to John on meeting him again make it clear that the latter is foremost in his mind:

You know that old expression, ‘The grass is greener on the other side’? […] It’s true. Here, you look down and see grass and dirt. Look straight ahead, you see green grass. Think about it.

While the scene is played for laughs – this being the kind of wilfully opaque thing you’d expect an eccentric jazz player to say – there’s intent behind the observation. Billy’s enigma lies in how he functions as both aspirational wise man and cautionary tale. At first, we are encouraged to think of him as a tragic figure, a man decimated by fame. He may have once stridden confidently out, shirtless under the outback sun, to play for a bunch of strangers he had just dropped in on from out of the sky, but he has since become frail, cloistered and wary, perpetually hiding behind a pair 1970s-style oversized sunglasses. He has abandoned jazz and the raw emotional power of his trumpet playing for esoteric experimentations with digital facsimiles of the sounds that brought him fame and purpose. What little he says about his previous career is curt and guttural, the ghost of a wound that was survived but never completely healed:

I reached for a beer in Munich, and my head kept going down and down and down and down. After playing the same old shit for forty years, my soul had pulled a switch on me. I was becoming a jazz museum piece.

Yet inside that weathered shell is the wisdom of someone who learned to walk away, to cut out of his life the things that had grown sour for him. Billy’s self-imposed exile, while sad in some respects, clearly makes him happier than if he were still out living the life of a performer. What we’re seeing is a man in the aftermath of burnout, not in the process of it. John may inspire him to go out into the world – even to play the trumpet for the first time in years – but Billy’s own redemption was won a long time ago.

After the night at the jazz club, Billy confides that he is planning to record one of John’s compositions. John has finally sold a song – and to his idol, at that. But when John starts talking about starting his own career in Paris, Billy advises, ‘It’s not gonna sound the same here. What you’re born with was the dingo sounds, outback sounds […] And even if you’re good, it’s still gonna be hard.’ Billy isn’t telling him that he can’t make it in Paris, but prompting him to consider whether he belongs there. The lesson he imparts to John is that career success is but one component of the artist’s dream – a lesson he failed to learn for himself, and a trap he also sees John heading for. Being the educated, older third dingo, Billy is able to drop some stones himself to save his friend, allowing him to return to his family renewed.

John’s dreams may be challenged by fate and the pressures of adulthood, but de Heer and screenwriter Marc Rosenberg never seem particularly interested in mining melodrama from conflict.

De Heer has spoken of Dingo as a film that is ‘less about jazz’ than one that ‘just happens to use jazz’. As he describes it, ‘It’s about the fulfilment of dreams and avoidance of regret – and jazz is just a part of telling that story.’[1]Rolf de Heer, quoted in ‘Rolf de Heer: Dingo and All That Jazz’, FilmInk, 2 February 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/rolf-de-heer-dingo-and-all-that-Jazz/>, accessed 20 June 2022. Dingo is about the need to sustain one’s dreams as part of a holistic approach to life, never losing sight of one’s responsibilities and natural environment. John’s dreams may be challenged by fate and the pressures of adulthood, but de Heer and screenwriter Marc Rosenberg never seem particularly interested in mining melodrama from conflict. The tensions that threaten to cost John his family ultimately amount to a wake-up call rather than any serious ultimatum; when he returns home, Jane is still there, having rejected Peter, who by this stage has completely disappeared from the film. With its airy tone and regular dips into magic realism, Dingo is more about internal conflicts than external challenges.

As fate would have it, that theme came to resonate most with de Heer himself. Dingo was a difficult film to shoot, with harsh outback conditions and the logistical nightmares that can come with international co-production. The 65-year-old Davis, in his only major film role, also took some time to adjust to the demands of miming playing music for film. As de Heer describes it,

We rehearsed and rehearsed, and time and again Miles would find himself playing an improvised counter-melody against the original trumpet line. It was beautiful but unusable. Those first few hours with Miles and the whole attendant circus were the most despairing hours of filming I’ve ever done.[2]Rolf de Heer, quoted in ‘Production Notes’, ‘Dingo’, Vertigo Productions website, <https://www.vertigoproductions.com.au/dingo_production_notes.php>, accessed 18 June 2022.

Furthermore, the film would suffer a crippling run of bad luck on its completion. Davis passed away just before its originally scheduled release in the US, resulting in a delayed international theatrical run. Subsequently, the opportunity to have his and Michel Legrand’s soundtrack to the film nominated for an Academy Award was missed as a result of misprinted ballots. And by the time a proper release could be organised, interest had waned, consigning the film to obscurity.[3]Despite several Australian Film Institute Awards nominations and prizes for sound and original music score, along with an AWGIE Award for best original feature film screenplay, the film fared poorly at the domestic box office and received mixed reviews. See Jaymes Durante, ‘Interview: Rolf de Heer on Miles Davis & Dingo (1991)’, Pelican, 14 March 2016, <https://pelicanmagazine.com.au/2016/03/14/interview-words-rolf-de-heer/>, accessed 30 June 2022.

Yet from the trauma of its creation came a new perspective for de Heer on his own career. Looking back on the production years later, he would say:

We made no money. It was a difficult year, the film was creditable, but it sank completely, and I thought: you can make a good film and it goes nowhere, you can make a good film and it can go somewhere; you can make a bad film and it can go somewhere, and you can make a bad film that goes nowhere. It’s completely out of your hands. It’s almost random. So, I thought, I’m gonna stop doing this, making films that are hard to make, and I’m gonna start making films that I care about, for myself. Small films. I’m going to enjoy the process. Dingo changed the way I approach filmmaking radically, and happily so.[4]Rolf de Heer, quoted in Durante, ibid.

It appears that life came to imitate art for de Heer, setting him on track for a career that has made him one of the most respected contemporary Australian filmmakers. Dingo is a film about learning one’s own voice; the fact that it taught this lesson to its own maker stands as testament to its quiet power, and its foundational role in de Heer’s developing importance to the Australian film landscape.

Endnotes

| 1 | Rolf de Heer, quoted in ‘Rolf de Heer: Dingo and All That Jazz’, FilmInk, 2 February 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/rolf-de-heer-dingo-and-all-that-Jazz/>, accessed 20 June 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Rolf de Heer, quoted in ‘Production Notes’, ‘Dingo’, Vertigo Productions website, <https://www.vertigoproductions.com.au/dingo_production_notes.php>, accessed 18 June 2022. |

| 3 | Despite several Australian Film Institute Awards nominations and prizes for sound and original music score, along with an AWGIE Award for best original feature film screenplay, the film fared poorly at the domestic box office and received mixed reviews. See Jaymes Durante, ‘Interview: Rolf de Heer on Miles Davis & Dingo (1991)’, Pelican, 14 March 2016, <https://pelicanmagazine.com.au/2016/03/14/interview-words-rolf-de-heer/>, accessed 30 June 2022. |

| 4 | Rolf de Heer, quoted in Durante, ibid. |