Unobtrusively situated next to the entrance of the main 2018 Adelaide Film Festival (AFF) venue on Hindley Street, the Jumpgate VR Lounge boasted a selection of packages that offered audiences an opportunity to engage with a range of virtual reality (VR) titles from Australia and around the world. Despite the name, there wasn’t much lounging to be done. There, VR didn’t involve lounging; VR required swivelling. Functional swivel stools were scattered around some unassuming tables while a row of computers for the more interactive VR texts lined the back wall. It was also not particularly ‘virtual’ – several staff members were present to divvy out headsets encasing mobile phones as well as handheld controllers (which I carefully looped around my arm, certain of my non-virtual clumsiness). For my first session, I was the only participant, with five staff waiting to help or casually chatting; the unwieldy physicality of the preparation process made me feel like I was the one on display.

Fritz Lang jokes in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963) that CinemaScope is ‘only good for snakes and funerals’. Using similar(ly incorrect but still somewhat revealing) logic, it might be worth suggesting that VR is particularly good for audiences who enjoy the sensation of being surrounded; ‘claustrophile’ is the closest term I could find. While VR can create, or at least suggest, open and expansive surroundings – I remember my unease upon returning to the ‘smallness’ of an ordinary computer room after my first stint playing some VR games a few years ago – the Australian VR pieces on offer at AFF tended instead to evoke enclosure. As viewers/participants themselves were often the focal point of the ensuing narrative, even the seemingly ‘open’ simulated surroundings produced a sense of confinement. We may don a headset to ‘see’ the VR text and ‘move’ through its world, but we also can’t help imagining a phantasmic crowd with their gaze turned steadfastly back on us.

Despite this sense of enclosure – whether in physical or narrative terms, or through an awareness of being a captive audience of one – the Australian VR pieces at AFF nevertheless covered a broad range of styles and genres. One of them, The Unknown Patient (Michael Beets, 2018), won AFF’s award for best VR title as well as screening in competition in the VR sidebar of the 2018 Venice International Film Festival, suggesting the possibility of a strong and diverse Australian presence in what is still a nascent artform. Of the four titles examined here, three present direct narratives about Australian history and/or culture through fairly familiar communication methods, notwithstanding the lure of VR’s encapsulating technological frame. Film criticism can be a game of historical surveying, finding antecedents for new products and examining their place in some speculative sense of ongoing development; VR is not videogames or video art, but elements of these must inevitably influence – through prior exposure – a participant’s subjective experience of this realm. Yet what I witnessed largely mirrored established film techniques, with creators using the still-developing medium as a marketable, novel platform for direct cultural, political and social exposure and awareness-raising.

Carriberrie

Carriberrie (Dominic Allen, 2018), described on its promotional website as ‘a multi-platform immersive journey across Australia celebrating the depth and diversity of Indigenous dance and song from the traditional to the contemporary’,[1]Carriberrie official website, <https://www.carriberrie.com>, accessed 11 February 2019. propels the viewer to a variety of stunning locations, utilising music and movement to weave together the piece’s sprawling story. There’s no question that Carriberrie is a vital cultural document as well as a vivid and energising experience, but there’s also an interesting tension at the heart of its ‘immersive’ form: despite its focus on the performances in the surrounding circular space, the viewer’s position at the centre of this space always feels foregrounded. Indeed, the viewer’s entry into the diegetic world is via a theatre stage, after which we’re shifted through the various performances. The vividness of all of these fiercely talented dancers and singers[2]A list of the featured performances can be found on Carriberrie’s official website, ibid. sits awkwardly with our awareness of them performing into this ‘empty’ core: the space now occupied by the viewer. The feeling of being looked at – or performed to – so intimately while simultaneously being both ‘there’ and not there reinforces too strongly that we are never really seen.

On another level, being propelled through a variety of different cultures experienced through landscape, dance and song may seem to re-create the tourist’s passing, flimsy gaze. Again, the performances are enrapturing, but the generated feeling of merely ‘browsing’ remains: passing moments rather than extended connections and understandings. Similarly, and perhaps counterintuitively, the sense of personal address that comes with VR can’t help but imbue gravitas to the watching of this artwork: Who wants to let down these wonderful dancers who are performing for us? And how can/should non-Aboriginal viewers feel about being a privileged audience of one for a practice so culturally significant to First Nations Australians?

None of these are criticisms of the text per se; instead, they suggest some of the baggage that comes, if not from VR technology itself, then from making the viewer’s gaze so central to VR storytelling and the difficulty of communicating culture using mere snippets and spectacle. Carriberrie employs wonderful footage that undoubtedly provides the viewer with a vibrant and visually engrossing experience – but it’s too soon to say exactly how well performances of this sort work in the VR space.

The Unknown Patient

Presented as the first episode of a possible five-part series, The Unknown Patient uses VR as a slightly unwieldy amalgam of prestige-style historical drama and interactive game, not quite inhabiting either form nor effectively distancing VR from them. Its interactive aspects are fairly perfunctory: in particular, the viewer is commanded to repeatedly ‘find that coin’ before the narrative can continue.

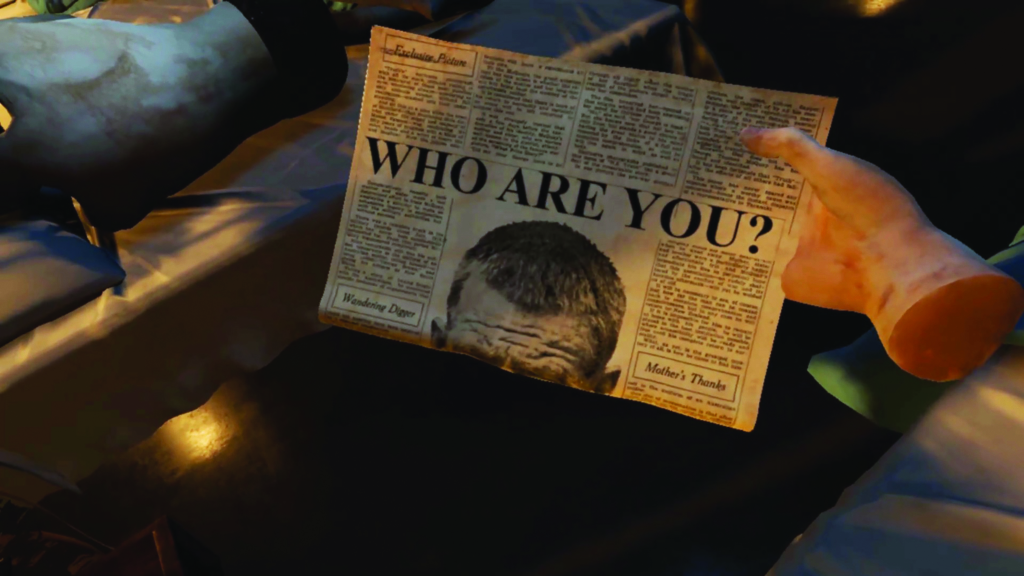

While The Unknown Patient does allow for some interaction with elements of the environment, its main task remains that of, essentially, looking, listening and swivelling. The piece’s central point of interest is its underlying narrative: the true story of an ANZAC soldier who was found wandering the streets of London in 1916 and ended up in a Sydney hospital for twelve years. Placing the viewer in the shoes of someone without a known name or backstory gives the mystery a personal impetus (a technique that obviously predates VR storytelling, but is given additional weight by the medium’s heightened faculty for point of view), as does the effectively perturbing ambience of the hospital setting.

As the storyline unfolds in a largely traditional manner, The Unknown Patient never quite allows the viewer to feel truly lost in the character’s identitylessness. A conveniently earnest and talkative nurse, Diana (Lily Sullivan), and some fragmentary flashbacks (which are fairly generic in terms of narrative, but also surprisingly effective in the way they appear within, and overwhelm, the surrounding virtual environment) ensure that the narrative’s momentum never threatens to disappear. But direct involvement here still feels like a token element in a passive narrative realm: interaction, but not yet ‘real’ contribution. Nevertheless, The Unknown Patient’s strong use of historical detail and visual design makes the prospect of further instalments an intriguing one for Australian VR.

Parragirls Past, Present: Unlocking Memories of Institutional ‘Care’

Parragirls Past, Present: Unlocking Memories of Institutional ‘Care’ (2017) – written, designed and produced by a team including Lily Hibberd, Bonney Djuric, Jenny McNally, Volker Kuchelmeister and Alex Davies – summons confronting memories of life in the Parramatta Girls Home, which operated under different guises from 1887 until 1983. It positions the viewer within the establishement’s high-walled grounds as former residents, returning some forty years later, recount the abuses and torments they experienced there. While ‘residents’ is the term used in promotional material, the stories relived in Parragirls Past, Present may lead viewers to feel that ‘prisoners’ might be a more apposite word.

The VR experience is largely fixed in its format: we drift through the dark premises, shifting through standard film-style transitions into new locations and buildings as the narration details life in that particular section or in the general confines of the institution. The generated sensation of drifting can initially be frustrating, but the feeling of powerlessness that this elicits ultimately contributes to the work’s overall depiction of physical and emotional confinement. The slow, powerless drift – almost like being wheeled around unwillingly – suggests the impetus of an ominous dream, an aesthetic that effectively paints the home as a nightmarish site of trauma from the not-so-distant past. Indeed, the filmmakers talk of their desire not to follow the standard CGI pursuit of ‘ever more realistic depictions’, instead opting for an ‘abstract reconstructed reality’ that ‘can be interpreted as being compatible with how human memory operates. It is mutable, constructed and fragmented.’[3]Parragirls Past, Present: Unlocking Memories of Institutional ‘Care’ official website, <https://parragirlsmovie.com>, accessed 11 February 2019.

Yet, at times, this dreamlike presentation can be evocative of a horror movie’s constructed CGI setting – we witness stock-standard motifs like shadowy spaces and techniques like the (highly overused) low drone on the soundtrack. This is far from tonally inappropriate, of course, but it does mean that the depicted location can occasionally feel generic rather than specific. At the end of the piece, the viewer floats back to see the home isolated in space, not only reinforcing its status as an imprisoning context for suffering but also reminding us of the lack of historical and cultural specificity within the text itself.

By allowing viewers to hear the voices of the victims directly, in an approximation of the real location within which they suffered, Parragirls Past, Present offers a vital contribution to Australia’s historical record and future understanding of institutional abuses.

One particularly upsetting detail (although there’s no shortage of upsetting stories) involves a subject describing having to respond to doubts about the abuse claims. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse may have released its findings into the Parramatta Girls Home,[4]Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Report of Case Study No. 7: Child Sexual Abuse at the Parramatta Training School for Girls and the Institution for Girls in Hay, October 2014, available at <https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/file-list/case_study_7_-_findings_report_-_parramatta_training_school_for_girls.pdf>, accessed 11 February 2019. but, ultimately, a traumatic history can never be declared closed. By allowing viewers to hear the voices of the victims directly, in an approximation of the real location within which they suffered, Parragirls Past, Present offers a vital contribution to Australia’s historical record and future understanding of institutional abuses.

Summation of Force

Perhaps the most formally ambitious of the titles being looked at here, Summation of Force (Trent Parke, Narelle Autio & Matthew Bate, 2017) engages most overtly with the possibilities that come with VR’s encapsulating space. Rather than relying on the viewer to swivel in order to ‘survey’ the text’s portrayed surroundings, Summation of Force is carefully designed to encourage smaller, less certain evaluations of the enveloping space, with certain visual elements appearing in particular parts of the frame rather than forming constitutive parts of a generalised environment.

Summation of Force’s move away from the focal points of the aforementioned three works – narration in Parragirls Past, Present; flashback and dialogue in The Unknown Patient; linked vignettes in Carriberrie – sees it drawing instead on the tradition of experimental filmmaking, and this arguably leads to it feeling more fully developed as a VR-specific work.[5]Even though it was produced in conjunction with an installation piece; see David Knight, ‘Trent Parke and Narelle Autio’s The [sic] Summation of Force’, The Adelaide Review, 21 June 2017, <https://www.adelaidereview.com.au/arts/visual-arts/trent-parke-narelle-autios-summation-force/>, accessed 11 February 2019. The film’s description in its promotional material of the way it examines, and (to some extent) elevates, sport and childhood growth may be avowedly blunt – its official synopsis describes it as a ‘a paean to collective dreams, youthful determination, and the bonds that sporting ambition can create’.[6]‘Summation of Force’, Closer Productions website, <http://closerproductions.com.au/films/summation-force>, accessed 11 February 2019. In reality, however, its abstract images, occasional use of extreme slow motion and lack of exposition will, for many viewers, present a somewhat less comfortable and comforting view of the childhood sporting realm.

Summation of Force is the only title of the four that doesn’t make the viewer’s presence central to the sense of the surrounding action … its packaging of simulated space far exceeds the surround-and-stare or drag-through approaches that have often been default choices for VR works to date.

Interestingly, Summation of Force is the only title of the four that doesn’t make the viewer’s presence central to the sense of the surrounding action, offering instead a somewhat more detached and, as a result, more dramatically intriguing experience. In fact, its packaging of simulated space far exceeds the surround-and-stare or drag-through approaches that have often been default choices for VR works to date. In the opening scene, for example, the viewer is in the middle of a suburban backyard, a batter on one side and some hanging laundry on the other, against the backdrop of a black night-time void. As the slow-motion approach of the bowler becomes apparent, the viewer is faced with two planes of action: it’s impossible not to regard the batter even if the approach of the ball seems to be the movement that dominates the frame. It’s this type of tension between spaces – rather than a uniformity – that sparks Summation of Force’s VR environment into life. As David Bordwell notes in relation to VR’s role of guiding viewers, ‘Narrative, we’ve known since forever, depends on controlling attention’[7]David Bordwell, ‘Venice 2018 College Cinema: Landscapes, Portraits’, Observations on Film Art, 7 September 2018, <http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2018/09/07/venice-2018-college-cinema-landscapes-portraits/>, accessed 11 February 2019. – and Summation of Force offers us an intriguing mix of controlled and uncontrolled experiences.

*

It’s difficult to look into any VR work’s promotional material (including those of the above titles) without running into some variation of the word ‘immersive’. This is entirely reasonable, but the near-ubiquity of the term carries certain problems, since it can feel like a general functional description of the overall nature of the technology has just been extrapolated (each time) into a defining feature of the individual VR work – a bit like (meaninglessly) referring to a film’s ‘visuality’. This ambiguity as to how we’re supposed to understand the word suggests that, just as VR has a long way to go in terms of determining exactly what its defining properties and possibilities are, the way we talk about and analyse it is also still evolving. The pursuit of some phantasmic idea of ‘immersion’ is likewise a fairly dominant trend in traditional film, which therefore couches VR as a logical extension of its forebear rather than a real game changer in an artistic sense. Like Bordwell, most viewers may still (for now) be finding ‘close affinities between VR and cinema’.[8]ibid.

It may be boorish to point out that, currently, public VR spaces such as the one I visited at AFF are far from able to compete with some of the higher-end professional products and home set-ups that accommodate powerful user-directed motion within virtual spaces, online communication, and a more immediate sense of action and interaction. But the uneasy dynamic between VR as film, VR as game, VR as interactive tool, VR as public installation and VR as immersive experience isn’t one that’s likely to be ‘settled’ in any specific way; rather, these shifting characteristics are likely to define the medium’s development into the future. Moreover, the range and variety of VR titles presented at AFF demonstrate Australia’s engagement with the VR realm’s multiple formats and approaches – as well as its ongoing pursuits in this media space to increase and promote cultural, historical and political knowledge through art and new technologies.

http://www.michaelbeets.com/the-unknown-patient-2/

http://closerproductions.com.au/films/summation-force

Endnotes

| 1 | Carriberrie official website, <https://www.carriberrie.com>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | A list of the featured performances can be found on Carriberrie’s official website, ibid. |

| 3 | Parragirls Past, Present: Unlocking Memories of Institutional ‘Care’ official website, <https://parragirlsmovie.com>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

| 4 | Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Report of Case Study No. 7: Child Sexual Abuse at the Parramatta Training School for Girls and the Institution for Girls in Hay, October 2014, available at <https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/file-list/case_study_7_-_findings_report_-_parramatta_training_school_for_girls.pdf>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

| 5 | Even though it was produced in conjunction with an installation piece; see David Knight, ‘Trent Parke and Narelle Autio’s The [sic] Summation of Force’, The Adelaide Review, 21 June 2017, <https://www.adelaidereview.com.au/arts/visual-arts/trent-parke-narelle-autios-summation-force/>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

| 6 | ‘Summation of Force’, Closer Productions website, <http://closerproductions.com.au/films/summation-force>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

| 7 | David Bordwell, ‘Venice 2018 College Cinema: Landscapes, Portraits’, Observations on Film Art, 7 September 2018, <http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2018/09/07/venice-2018-college-cinema-landscapes-portraits/>, accessed 11 February 2019. |

| 8 | ibid. |