Courtney Barnett is, director Danny Cohen says, ‘an ordinary person in an extraordinary position’. This is a tried-and-true storytelling device, and the essential premise of Cohen’s documentary Anonymous Club (2021), a chronicle of the 33-year-old singer/songwriter’s experiences with the existential realities of international success. But unlike, say, a tale about an ordinary person who transforms into a hero in the face of a strange, surreal world, Anonymous Club is a far more honest portrait of ordinariness, a work of humanity that dares to show its subject as someone filled with self-doubts, anxieties and insecurities. ‘You could just look at Courtney on stage and assume that everything’s great, that she’s full of confidence,’ Cohen offers. ‘But people are human, and just because you’re quote unquote “a rock star” doesn’t mean that you don’t go through the same ups and downs as everybody else.’

It makes sense that a film about Barnett wouldn’t be the standard brand-burnishing entertainment. Since breaking out with her record The Double EP: A Sea of Split Peas in 2013, the Melburnian artist has managed to maintain an air of normalcy as she’s found astonishing commercial and critical success. A huge part of the reason people identify with Barnett’s witty, wordy songs is their honesty; to listeners, Cohen thinks, she feels ‘like a mate, like an everyperson’. In the opening intertitles that introduce Barnett to Anonymous Club viewers, amid the glad facts of album sales and Grammy nominations, she’s described as ‘notoriously shy’. That makes her an unlikely subject for a rockumentary – an oft-detestable genre of motion-picture products that, more often than not, feel like promotion or band merch.

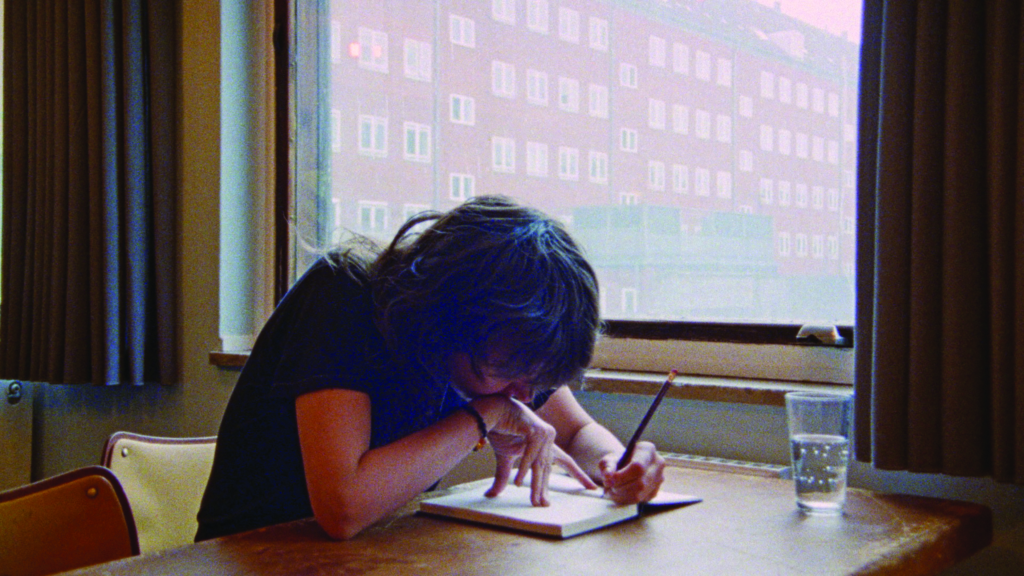

‘I never really believed it was a film until recently,’ says Barnett, forever self-effacing, in an interview for this article. She says she was ‘naive’ to the fact that what she was doing – recording her thoughts, daily, into a dictaphone, with Cohen periodically filming – was really going to end up on a cinema screen. The process lasted three years, from touring in the wake of her second full-length album, 2018’s Tell Me How You Really Feel, to finishing her third, Things Take Time, Take Time, in 2021.[1]Barnett’s first LP was 2015’s Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometime I Just Sit. Through those years, Barnett thought of it all from a personal position, that she was documenting experiences that she could look back on in years to come; so she submitted to the process, even though being in front of the camera is not something that she’s entirely comfortable with. ‘I normally get kind of shy and weird,’ Barnett admits. ‘I have gotten more used to it over the years, but it never feels completely natural […] So many people have that same feeling in front of a camera: weird self-reflection.’

Barnett … is described as ‘notoriously shy’. That makes her an unlikely subject for a rockumentary – an oft-detestable genre of motion-picture products that, more often than not, feel like promotion or band merch.

That self-reflectiveness, that weirdness, is found throughout Anonymous Club. Early in the film, we hear Barnett’s first voice recording, in which she warily confesses: ‘I’m trying to figure out how to delete everything I’ve said, because I’m self-conscious about it.’ This sets the tenor for the film. A rollicking opening montage is set to ‘City Looks Pretty’: the song’s upbeat early stretches are matched to familiar rockumentary imagery (festival shows, big gigs, backstage hijinks, bustling cities), but when the song slows radically for its subdued second half, we see the flipside of those same images (sound check in empty venues, post-gig clean-ups and load-outs, long drives, hotel rooms, feeling alone). So goes life on the road: the whiplash from the mundanity of travel to the exhilaration of performance. But, for Barnett, even the latter isn’t guaranteed to provide the touring cycle’s natural peaks. ‘It’s amazing how different a live performance can be from day to day,’ she confides in an early section of the film called – with due irony – ‘You Must Be Having So Much Fun’. ‘One day it can be so totally liberating and electric and energetic and alive, and then another day you can just be so rigid and full of fear and feel so far away.’

If Barnett’s full of candour in her songs (a notable line from ‘City Looks Pretty’, on the destabilising nature of fame: ‘Friends treat you like a stranger and / Strangers treat you like their best friend’), her verbal confessionals that fill the film are truly revelatory – the artist speaking aloud sentiments that are in turn self-critical, vulnerable, emotional. ‘I’d go through so much love and hate of performing, like falling into the groove of the same thing,’ she says, with hindsight, of the routines of tours. At a bad show, she creates a narrative in her head where the audience ‘thinks I’m a big joke and talentless’. Shows, she says, can feel ‘pointless’, like ‘this scripted performance of what we think we’re supposed to see on stage’. Tours can seem pointless too, except when they don’t: ‘I do want to do this tour, but I also don’t want to do it at the same time. And I don’t really know why.’ She feels like the interviews for Tell Me How You Really Feel have let down the whole album, failing to live up to its themes and ideals: ‘What could have been a fantastic conversation around fragility and depression and mental health […] just ended up being swept to the side because I was too scared to talk about anything real or heavy.’ She wakes up in a fancy, gilded hotel in Berlin feeling down, trying to accept that ‘it’s okay to just feel sad’. She apologises to Cohen, via the dictaphone recording, for ‘being such a bummer lately’. In Dallas, playing her ode to inner-Melbourne deceased-estate gentrification, ‘Depreston’, she cries on stage. ‘I felt so sad I just started crying,’ Barnett says. ‘It felt quite liberating crying in front of 2000 people. And people are like, “What the fuck? What’s wrong with her?”’ Later, she’ll cover Hank Williams’ ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’, obviously relating to its sentiments. Back home in Melbourne, off tour, Barnett confesses she isn’t ‘in the mood to indulge [her] egotistical’ side and doesn’t ‘see the point in doing’ the voice recordings, apologising for their content. ‘All I can do is whinge,’ she laments. ‘It’s such a fucking bore; it’s such a bore, just listening to myself.’

All of this makes Anonymous Club a film utterly unlike a regular rockumentary. There are no celebrity testimonials (‘Those talking heads, I always feel like they could be talking about any musician,’ Cohen mocks), no potted history, no needle-drops on the hits, no attempt at making an entry-level primer to turn a viewer into a consumer. ‘I wasn’t really interested in making a film that was a retrospective of her career, using archival footage, telling a story of her beginnings and how she moved up,’ Cohen says. The only music movie the filmmaker and his subject spoke of in advance was DA Pennebaker’s famous fly-on-the-wall portrait of Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back (1967). They intended to make a film, Barnett explains, ‘about the creative process, creative fear, insecurity, the joys of making different types of art’. She trusted Cohen to make something ‘beautiful and thoughtful’ and went along with it for years, thinking of this as a document of a particular period in her life. ‘Even those moments of, like, “who am I to think I deserve to have a film about me” self-doubt,’ Barnett offers. ‘I really wanted it to document that, too.’

In turn, Anonymous Club is something close to the opposite of the heroic hagiography of a ‘great’ artist: a relatable portrait of a person struggling with their mental health, in which the rinse-repeat routine of rock’n’roll is a portable symbol for anyone who feels like they’re in groundhog day. ‘It’s a story of what happens when your passions are intrinsically linked to your anxieties,’ Cohen says. ‘And how you go about working through those, unpacking [them] and finding your feet.’ Even though they’d been acquaintances and collaborators for years (the director having made numerous music videos with the singer/songwriter), Cohen was ‘surprised and moved’ when he started receiving Barnett’s voice recordings. ‘Her nerves – nerves at playing shows, playing the songs, the record being out, how people were going to react – [were] something that I didn’t really see in her as a friend,’ he says.

To visually capture this state, and Barnett’s experiences, Cohen sought to try and be as much of a ‘fly on the wall’ as he could; though, he laughs, ‘I’m six-foot-five with a film camera on my shoulder; I never blend in’. Cohen worked with a camera engineer and a computer technician to develop a device that instantly synced each camera recording and sound recording, a technical achievement that allowed him to be a one-man crew, solitary in the corner, without needing someone to hold a boom or mark recording with a clapper. He discovered that he could never truly disappear – ‘Being in the room changes everything. It changes how Courtney acts, how other people react around Courtney, how I interact with Courtney’ – but, still, his solitary method ‘created a level of intimacy’, further fostering the confessional air cultivated by the voice recordings.

Barnett saw this intimacy as mirroring her art, noticing the parallels between her songs, her spoken sentiments, the filming and the interviews she does that often end up on camera. ‘I feel like it all ties together,’ Barnett tells me. ‘It’s all quite a vulnerable process and activity.’ Some of the interviews shown within Anonymous Club are intense: on German TV, she’s asked a wildly inappropriate opening question in front of a studio audience; on a US radio station, when talk turns to her song ‘Nameless, Faceless’, the interviewer wants Barnett to explain ‘how male fear is turned into violence’, as if she’s an anthropologist, a psychologist, an expert. Barnett laments, within the movie, that she feels like she’s bad at interviews (‘I don’t know how to say these things I want to say, and I know I end up sounding like a fucking moron’); and, in conversation for this piece, she talks of being forever wary about her conversational words carrying such weight and falling short – the ‘frustrations of saying something and being misinterpreted, or misheard’.

Another intense interaction depicted in Anonymous Club is when Barnett meets and greets superfans. With our subject having been established as humble, reserved, self-effacing and awkward, there’s dissonance with those stans who openly display their desperation and devotion, proselytising, to the source herself, how much Barnett’s lyrics mean to them. ‘It used to make me feel kind of awkward; layers of impostor syndrome and self-criticism used to creep in,’ Barnett admits, in interview. But, over time, she learned to ‘take [her] own ego out of that situation’, allowing it to be about this other person, the power of their feelings and identification with the music. ‘My own story can just get in the way of that, and if I can take that out of it, then you’re just left with a beautiful, meaningful connection,’ says Barnett. ‘I’m so grateful that it happens, that people have such intense reactions or revelations or emotions to one little thing that I might write.’

The release of Tell Me How You Really Feel invited the identification of fans directly into Barnett’s life and furthered the idea of performer and listener operating on the same wavelength, with the album website hosting a comment box asking listeners to do as its title said.[2]See Tell Me How You Really Feel official website, <https://tellmehowyoureallyfeel.fm/>, accessed 26 August 2021. The ‘humbling and beautiful’ response was thousands of confessionals, showing just how much people are willing to share when they think someone will listen. ‘A lot of people feel alone, but maybe they’re not so alone,’ Barnett says, on screen.

Anonymous Club further humanises a figure who, through her music, already appeared plenty human – drawing viewers into a world in which success isn’t some celebration, or arrived-at destination, but an amplifier of anxieties and self-doubts.

This is, essentially, the theme of the film, its hoped-for takeaway. Anonymous Club further humanises a figure who, through her music, already appeared plenty human – drawing viewers into a world in which success isn’t some celebration, or arrived-at destination, but an amplifier of anxieties and self-doubts. The honesty that Barnett shows in her music is echoed by the honesty she displays on screen. ‘I’m not incredibly great at not telling the truth,’ Barnett tells me.[3]‘Double negative … it’s tricky.’ – Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera), in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (Edgar Wright, 2010). ‘I feel like sometimes I talk a little bit too openly. I don’t know if that’s a bad thing.’

In this space, it’s definitely not; Anonymous Club’s goal, beyond refusing to roll out a rote rockumentary, is ultimately revealed as participating in a greater cultural conversation about mental health. ‘It’s not the most glamorous or comfortable thing to watch, sometimes,’ Barnett admits, of the doc. Those things that other films might cut out – ‘because they feel a little bit uncomfortable, or a little bit private, or a little bit vulnerable’ – are kept in, to live up to the film’s hopes. ‘If there’s one moment where people can relate it to themselves, or understand one thing about themselves better, all those things are always going to be worth it,’ Barnett says. ‘It’s really important,’ Cohen furthers, ‘to talk about those [struggles], and show ways that other people get through things. I hope people can relate to [the film in] their own personal way, even if they’re not a musician or an artist.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Barnett’s first LP was 2015’s Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometime I Just Sit. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Tell Me How You Really Feel official website, <https://tellmehowyoureallyfeel.fm/>, accessed 26 August 2021. |

| 3 | ‘Double negative … it’s tricky.’ – Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera), in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (Edgar Wright, 2010). |