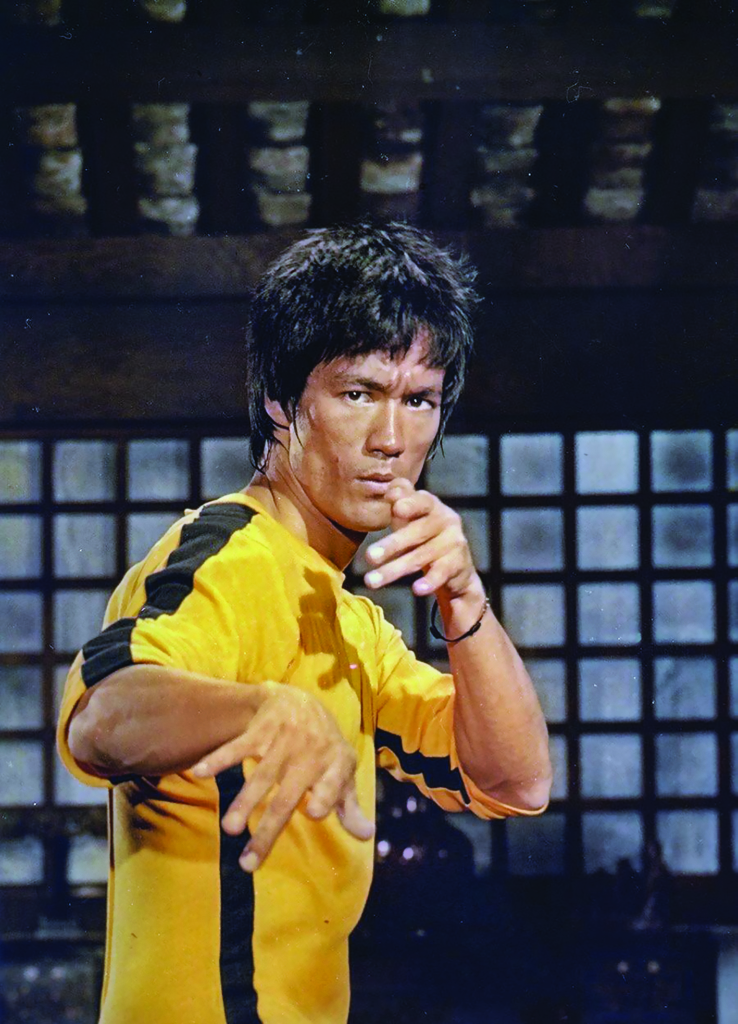

There is a scene in Once upon a Time … in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019) in which Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), an underemployed stunt performer, finds himself on the set of 1960s TV series The Green Hornet with Bruce Lee (Mike Moh). The Lee of the film is cocky; Booth observes as the famous Eurasian actor lectures other members of the cast and crew, and doesn’t take long to make his disdain clear. The two find themselves in a ‘friendly’ fight, during which Lee ends up being thrown against a car. It is by no means a beat-down, but Booth’s intention – and, by extension, Tarantino’s – is clear: they are taking this arrogant kung-fu guy down a few pegs.

While the plot of Once upon a Time … in Hollywood necessarily takes many blatant liberties with the truth, it enters murky territory with scenes like this one. Lee the character only has a few minutes of screen time, but, for those who don’t know much about his story, this version of him, boastful and fight-picking, will lace itself around their impression of the real man. And so, following the film’s release, this scene quickly prompted backlash, most prominently from Lee’s daughter, Shannon. She argued that this inauthentic portrayal wasn’t fair to her father’s legacy. Her concern, as she explained to Vanity Fair, was that people wouldn’t be able to tell fact from fiction, and that Moh’s Lee is a caricature: ‘maybe Tarantino took all the things that he knew or heard about Bruce Lee and smashed them into one encounter’.[1]Shannon Lee, quoted in Julie Miller, ‘Bruce Lee’s Daughter Has More Questions About Quentin Tarantino’s “Troubling” Depiction of Her Father’, Vanity Fair, 1 August 2019, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/08/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-quentin-tarantino-bruce-lee>, accessed 7 November 2019.

Just as it is easy to caricature Lee, it’s easy to write off kung-fu films as silly, frivolous and niche. It should also come as no surprise that Lee and kung-fu films are inextricably linked in the public consciousness; after all, they’re what put him on the map. But the link goes further than simply that between a performer and the subgenre he is best known for. As Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks (Serge Ou, 2019) impressively shows, kung-fu films have resonance beyond the screen, and their themes remain relevant even now.

Early on in the documentary, a few minutes of screen time are dedicated to Hong Kong’s 1967 protests. It starts out by intercutting footage of the violent rallies with fight scenes involving martial-arts actor Cheng Pei-pei, then moves on to a brief, somewhat overly simplified explanation of the protests themselves. Viewers learn how over fifty people died in the clashes, how protesters came up against the police force and how journalists were under attack.[2]For more on the 1967 protests, see ‘Fifty Years On: The Riots That Shook Hong Kong in 1967’, The Foreign Correspondents’ Club, Hong Kong website, <https://www.fcchk.org/correspondent/fifty-years-on-the-riots-that-shook-hong-kong-in-1967/>, accessed 7 November 2019. Written down in this way, it seems like a strange moment in time to include in a documentary about kung-fu films, an arguably niche subgenre of cinema. But Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks – which brings together an impressive collection of interviewees, including performers, academics and historians – digs deeper than the light overview its title might suggest. Its merging of film footage with news from the time only accentuates this depth, showing the audience that the line between movies and the world they exist within is very narrow. ‘I love films about how cinema affects culture and vice versa,’ producer Veronica Fury tells me. ‘This is an exploration of how Hong Kong cinema exploded into the West and influenced not just cinema but pop culture around the world today.’

Almost every time shots change, there is a new interviewee with a different dimension to add – we hear from director and artist Charlie Ahearn; actor, martial artist, director and producer Sammo Hung; director and martial-arts choreographer Yuen Woo-ping; actor and martial artist Ron ‘The Black Dragon’ Van Clief; and martial-arts expert turned performer Cynthia Rothrock. The list of names is long and impressive. The documentary takes us through the subgenre’s origins in Peking opera, shines a light on some interesting quirks and trivia about production, then carries viewers forwards and outwards, showing how kung-fu cinema has made its mark on some unexpected arenas. In particular, interviewed in the film are hip-hop artists such as Alien Ness, who explain how the subgenre’s theme of overcoming odds spoke to them and how the beauty of its fight scenes helped shape hip-hop dance. Ou also draws a connection between kung-fu films – specifically, the work of Jackie Chan – and the street-running sport of parkour. In recounting this wide-reaching impact, Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks describes the influence of the subgenre as something akin to a virus.

It’s a strange quirk of timing that, when Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks premiered at last year’s Melbourne International Film Festival, widespread protests were again breaking out in Hong Kong – this time, in response to an unpopular proposed extradition bill. Though quite different in underlying motivation than its 1967 counterpart, the 2019 unrest has parallels with its predecessor: clashes between protesters and the police, violence, and a pushback against authority.[3]See Jason Wordie, ‘The 2019 Hong Kong Protests and the 1967 Riots: Some Things Never Change’, Post Magazine, 16 August 2019, <https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3022953/2019-hong-kong-protests-and-1967-riots-some>, accessed 7 November 2019. The timing is a complete coincidence; Fury clarifies that the film had long been completed before the recent protests started. But this unintended resonance does allude to how and why kung-fu is an evergreen genre.

The reason the 1967 Hong Kong protests are brought up early on in Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks is that they are credited with the boom in the subgenre’s popularity. The documentary contends that, through their stories, kung-fu films tap into the very human feeling of being trapped by circumstance.

The reason the 1967 Hong Kong protests are brought up early on in Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks is that they are credited with the boom in the subgenre’s popularity. The documentary contends that, through their stories, kung-fu films tap into the very human feeling of being trapped by circumstance. ‘I think a major theme in a lot of these films is that your hand is forced,’ says Fury. Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks shows us footage of the slight Cheng sitting by herself in a tea house before fighting a roomful of men, as well as scenes from The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (Lau Kar-leung, 1978) of a man making it through the many obstacles of Shaolin training. It explicitly ties the success of The One-Armed Swordsman (Chang Cheh, 1967) to the 1967 riots because its underlying themes reflected what the Hong Kong–based audience was feeling.

Viewers relate to the subgenre because, at some stage, most people have felt like they are being picked on, or like they are facing insurmountable odds. The plot of most kung-fu films is that of an individual taking on something larger – fighting what seems to be an unwinnable battle. For the most part, Ou’s documentary argues, kung-fu films are underdog stories: David taking on Goliath; Bruce Lee taking on an entire street gang.

Unsurprisingly, the career of Lee himself is one of the film’s focuses. Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks tracks how Shaw Brothers, at the time Hong Kong’s biggest film-production company, decided not to sign Lee, prompting the martial artist and actor to move to Hollywood, where he saw a degree of success – and a proportionate degree of discrimination. While Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks doesn’t overtly state this, it demonstrates how even one of kung-fu’s biggest stars had an underdog story, reminding viewers that the mirroring of society and kung-fu is evident not just in plots but also in production. Via interviews with those who knew or were inspired by Lee, Ou paints a comprehensive portrait of the actor’s complex relationship with the industry: The way he was rejected by Shaw Brothers because kung-fu wasn’t seen as impressive at the time. How he was lauded in the US because his kung-fu skills presented the American industry with something new. The fact that he helped make kung-fu popular in Hollywood but then was rejected by US television because his accent was too strong. How he went back to the Hong Kong film industry and made his breakthrough. Then the tragedy of his untimely death at the age of thirty-two, attributed to cerebral oedema.

The career of Lee himself is one of the film’s focuses … While Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks doesn’t overtly state this, it demonstrates how even one of kung-fu’s biggest stars had an underdog story.

There are plenty of uncomfortable truths highlighted in Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks, although some are lighter than others. In one scene, it is revealed that, when English versions of Chinese-language kung-fu films were dubbed, voice actors weren’t given scripts; instead, they were left to decide for themselves what words best fit the lip movements on screen. It’s no wonder, then, that older kung-fu movies are often seen as lowbrow or ridiculous. Lee’s story, in contrast, emerges as the documentary’s heaviest. Ou takes viewers through the disappointment felt by Lee when he was passed over for a role in the 1970s TV series Kung Fu in favour of a white actor, David Carradine, in yellowface. The interviewees recount that Carradine was rumoured to have shown up to his first audition stoned and done a terrible job, and yet, despite this, and despite not having any martial-arts training, was given the role over Lee. The film also exposes how, in the aftermath of Lee’s death in 1973, Hollywood directors and producers had almost no shame in exploiting his legacy in order to make a quick buck. Their actions included repurposing old footage of him for new films, rewriting the films he was working on just before he died and even splicing in actual footage of Lee’s funeral into his incomplete final movie, the ironically titled The Game of Death (Robert Clouse, 1978).

After watching the documentary, it becomes clear that cases like those experienced by Lee are still happening today. While not directly mentioned in the documentary (which, interestingly, does feature actor Jessica Henwick – who plays Colleen Wing in the similarly titled show – as an interviewee), Netflix series Iron Fist is a noteworthy case study. Not only does its popularity provide further proof that the public still has an appetite for martial arts in mainstream media, but it also suggests that, in the forty years since Lee’s death, not that much has changed. Much like how Lee was rejected in favour of Carradine, the starring role in Iron Fist was offered not to the martial-arts-trained Eurasian actor Lewis Tan but to the non-martial-arts-trained white actor Finn Jones.[4]To prepare for the role, Jones underwent intensive martial-arts training in the lead-up to filming Iron Fist’s first season; see James Hibberd, ‘Finn Jones Talks Iron Fist (His Training Is Insane)’, Entertainment Weekly, 12 April 2016, <https://ew.com/article/2016/04/12/finn-jones-iron-training/>. Tan was in contention for the lead role but ended up being cast as minor villain Zhou Cheng; see E Alex Jung, ‘Meet Lewis Tan, the Asian-American Actor Who Could Have Been Iron Fist’, Vulture, 20 March 2017, <https://www.vulture.com/2017/03/lewis-tan-marvel-iron-fist-interview.html>, both accessed 7 November 2019.

Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks is a strong documentary in and of itself: it’s both educational and entertaining, and utilises a diverse cross-section of perspectives as part of its rich examination of the importance and impact of kung-fu cinema. But what makes the film remarkable is the way it shines a light on continuing problems: The snobbishness of viewing movies through the reductive lens of ‘highbrow’ vs ‘lowbrow’. The subtle racism that still plagues casting in Hollywood. How kung-fu films keep finding new life and new resonance because their core theme of societal injustice still taps into strong public sentiment. How the more things change, the more they stay the same. ‘It’s always time to tell these stories,’ says Fury. ‘There’s always a marginalised group.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Shannon Lee, quoted in Julie Miller, ‘Bruce Lee’s Daughter Has More Questions About Quentin Tarantino’s “Troubling” Depiction of Her Father’, Vanity Fair, 1 August 2019, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/08/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-quentin-tarantino-bruce-lee>, accessed 7 November 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on the 1967 protests, see ‘Fifty Years On: The Riots That Shook Hong Kong in 1967’, The Foreign Correspondents’ Club, Hong Kong website, <https://www.fcchk.org/correspondent/fifty-years-on-the-riots-that-shook-hong-kong-in-1967/>, accessed 7 November 2019. |

| 3 | See Jason Wordie, ‘The 2019 Hong Kong Protests and the 1967 Riots: Some Things Never Change’, Post Magazine, 16 August 2019, <https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3022953/2019-hong-kong-protests-and-1967-riots-some>, accessed 7 November 2019. |

| 4 | To prepare for the role, Jones underwent intensive martial-arts training in the lead-up to filming Iron Fist’s first season; see James Hibberd, ‘Finn Jones Talks Iron Fist (His Training Is Insane)’, Entertainment Weekly, 12 April 2016, <https://ew.com/article/2016/04/12/finn-jones-iron-training/>. Tan was in contention for the lead role but ended up being cast as minor villain Zhou Cheng; see E Alex Jung, ‘Meet Lewis Tan, the Asian-American Actor Who Could Have Been Iron Fist’, Vulture, 20 March 2017, <https://www.vulture.com/2017/03/lewis-tan-marvel-iron-fist-interview.html>, both accessed 7 November 2019. |