Chris Lilley has been both feted as a comic genius and condemned as an exploitative peddler of disgusting, tasteless rubbish – most recently for Summer Heights High. This eight-part comedy series polarized viewers when it screened on ABC1 over September and October 2007.

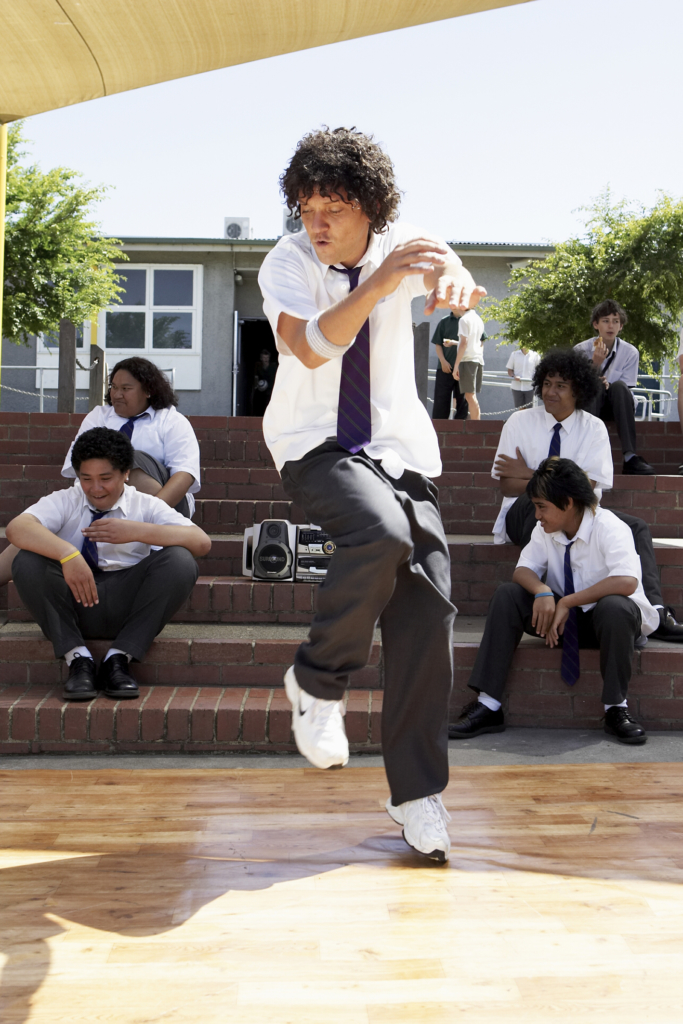

Summer Heights High was undeniably popular, gaining a forty-seven per cent viewer share of high school students (13–17 years), and it was the broadcaster’s highest rating show of the year with the coveted 0–39 youth demographic. It was also available online as a vodcast.[1]ABC’s blog, OzTAM data for Summer Heights High, Throng, 25 October 2007, <http://www.throng.com.au/summer-heights-high>, accessed 20 January 2008. The crowds at Lilley’s public signings at ABC Shops around the nation made the news, as queues of fans snaked around Westfield mezzanines, waiting for up to three and a half hours. Some dressed as their favourite Lilley character – obnoxious schoolgirl Ja’mie King, break-dancing delinquent Jonah Takalua or odious drama teacher Mr G.[2]AAP, ‘Hundreds Queue to Meet Ja’mie’, The Age, 26 October 2007, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/hundreds-queue-to-meet-jamie/2007/10/26/1192941329984.html>, accessed 30 May 2008.

At the same time, the series generated a storm of media controversy. There were calls for censorship over the depiction of a school musical about a drug-overdosing teen called Annabel, a storyline with unintentional parallels to the real-life ecstasy death of young Sydney woman Annabel Catt (which made headlines in early 2007 after the filming of Summer Heights High had ended). Viewer complaints filled online forums with claims that Lilley had ‘gone too far’ with his brutally glib approach to such issues as drug overdoses, rape, teenage sex, paedophilia, racism and disability.[3]Edmund Tadros, ‘Fury at ABC Skit Mocking Drug Death’, The Age, 21 September 2007; readers’ comments, ‘Chris Lilley Drug Death TV “Slur”’, The Daily Telegraph, 21 September 2007, <http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/comments/0,22058,22456495-5006009,00.html>; readers comments, ‘Are You Prepared For This?’, Herald Sun, 26 August 2007, <http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/comments/0,22023,22309508-5000117,00.html>. All sites accessed 20 January 2008.

Lilley’s previous series, 2005’s We Can Be Heroes: Finding the Australian of the Year, was on the whole critically acclaimed and garnered respectable ratings. The DVD sat alongside Little Britain as the ABC’s top-selling DVD of the year, and was proudly mentioned four times in the ABC’s annual report for 2005–2006. We Can Be Heroes was touted as having ‘helped to redefine the Australian “mockumentary” genre and [showcased] comedian Chris Lilley’s extraordinary talent’.[4]ABC Annual Report 2005–06, p.76, <http://www.abc.net.au/corp/annual_reports/ar06/>, accessed 20 January 2008. The series was sold to the UK, the US and Finland, and won a number of awards, both local and international, including the prestigious Rose d’Or for Best Male Comedy Performance in 2006. It is also regularly repeated on Foxtel’s The Comedy Channel.

While considerably tamer than Summer Heights High, We Can Be Heroes still sought to provoke, prickle and discomfort. This was less through a choice of broadly controversial subject matter than the way it dealt with complex, needling issues such as representation and race – taboos often dismissively labelled ‘politically correct’ by those who don’t feel their sting. The series followed five ‘deluded self-believers’ in their quest to be named Australian of the Year, the real-life award bestowed annually in Canberra.[5]Chris Lilley quoted in Greg Hassel, ‘Local Heroes’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 2005. All played by Lilley, the characters included Ja’mie King, who also featured in Summer Heights High; Pat Mullins, a housewife overcoming disability by rolling from Perth to Uluru; and Ricky Wong, a 23-year-old Chinese–Australian physics PhD student who was nominated for his solar panel research but whose real interest lies in amateur musical theatre.

It was Lilley’s performance as this last ‘model migrant’ character, conjuring up regressive yellowface ghosts – think Mickey Rooney’s screeching and bucktoothed Mr Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Blake Edwards, 1961) – that was the focus of some controversy in reviews and interviews.[6]Vicki Englund, ‘Wizards of Oz’, The Blurb: Your Source for Australian Arts and Entertainment, 2005, <http://www.theblurb.com.au/Issue56/WCBH.htm>, accessed 20 January 2008; Lilley interviewed by Don Romeo, ABC NewsRadio, 27 July 2005, transcript <http://standanddeliver.blogs.com/dombo/2005/07/pictures_of_lil.html>, accessed 20 January 2008. Issues around race and representation became more complicated still as the series progressed, when Ricky and his Chinese theatre group, CHISOC, developed a musical production called Indigeridoo, which claimed to ‘tell the true Aboriginal story’. Indigeridoo gave us the bizarre spectacle of white-in-yellow-in-blackface: Lilley playing Wong performing, in turn, an indigenous Australian character called ‘Walkabout Man’.

Whether we find his work funny or not, its controversy and success suggest Lilley’s particular style of television comedy warrants some critical examination.

I admit here to having mixed feelings about Lilley’s programs, having by turns laughed out loud and recoiled in horror during both Summer Heights High and We Can Be Heroes. But whether we find his work funny or not, its controversy and success suggest Lilley’s particular style of television comedy – its riskiness, aesthetic complexity and broader social implications – warrants some critical examination. Recent comedy theorists tend to agree that it is difficult to stabilize or fix the meanings or cultural effects of comedies, as viewers receive them differently depending on their apprehension of authorial intent and the extent to which characters or comic narratives confirm or challenge their pre-existing world view or daily experience.[7]Susan Purdie, Comedy: The Mastery of Discourse, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1993; Brett Mills, Television Sitcom, bfi Publishing, London, 2005, pp.135–55; Alan McKee, ‘“Superboong! ….” The Ambivalence of Comedy and Differing Histories of Race’, Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media and Culture, vol. 10, no. 2, 1996, pp.44–59. There is far less common agreement on what is funny than what is tragic, and it can be difficult to agree upon the specific target of comedy’s barb. The polarized reception of Summer Heights High, in particular, bears this out.

Rule-breaking and permissive contexts

Marguerite O’Hara positions Lilley’s work in a lineage of ‘mockumentary’ like This is Spinal Tap (Rob Reiner, 1984) and Waiting for Guffman (Christopher Guest, 1996), while also arguing that Lilley’s performances of the main characters puts them ‘in a league of their own’.[8]Marguerite O’Hara, ‘School’s Out There: Summer Heights High’, Metro, no. 155, 2007, p.70. While not disagreeing with this assessment, it seems important (in light of its controversy) to think of Lilley’s comedy first in relation to humour, before situating it generically. Like Sue Turnbull in her work on Kath & Kim,[9]Sue Turnbull, ‘Look at Moiye, Kimmie, Look at Moiye!: Kath and Kim and the Australian Comedy of Taste’, Media International Australia, no. 113, November 2004, pp.103–4. I find Susan Purdie’s insights into the operation of comic discourse useful here. Purdie’s basic argument is that comedy is produced through breaking a rule and marking the break.[10]Purdie, op. cit. This explains the importance of reaction shots in television comedy – cutting to a horrified or unimpressed response to a character’s speech or actions emphasizes that a rule of behaviour or speech has been broken. Purdie goes further and says that in breaking the rule, a situation has to be in play where transgression is momentarily permitted, otherwise the creation of ‘funniness’ fails.[11]ibid., p.13. Jokes fail if nothing transgressive is noted or, conversely, if inhibitions against the transgression are so strong that they remain enforced. The presence, or not, of permissible transgression in the mind of the joke’s receiver accounts for differences in reception: blankness, laughter or umbrage. Purdie also argues that laughter indicates not just a self-congratulatory recognition of the line and the rules, but acknowledges the power of a joker whose ‘mastery of discourse’ is such that they have created a particular context that permits temporary transgression.

A simple linguistic example can be found in the 2005 cult US comedy series Stella. In mid 2007, one recurring advertisement for the show in Australia on Foxtel’s The Comedy Channel showed a number of sketch fragments. In one of these, bespectacled comedian David Wain, clearly aware of the stringent rules against obscene language that govern American television, creates a linguistic context in which he can get away with seeming to vocalize the most offensive word: ‘I know I can hunt, but can Mike hunt?’ The line is delivered in a laboured, facetious fashion, with an arched eyebrow. Wain’s performance is at once making sure the transgression is marked as such, while also acknowledging the lameness of the joke and suggesting through irony that he himself does not subscribe to the taboo.

Arguably, the stronger the taboo a comedy deals with, the more a permissible context is required. This article argues in part that Lilley’s comedy relies on a combination of character identity, actor identity, performance, documentary codes and extra-textual material, creating multi-layered permissive contexts in order to produce both controversy and defensible laughter.

Note, for example, how Lilley tends to exploit the gaps between his social identity and the identities of his characters, using the latter as permissive contexts. For instance, at the end of Summer Heights High, Ja’mie has been jilted by her female date for the school formal and has returned to romantically pestering Year 7 student Sebastian (Jansen Perrone). When Ja’mie’s friends suggest he is too young for her and label her a ‘cradle-snatcher’, she retorts with a typically dismissive toss of her mane, ‘I’d rather be a paedophile than a lesbian.’

Elsewhere in the series we see Lilley as Jonah drawing cartoon penises on the bellies of pre-teen boys at a swimming carnival and insisting they photograph his posterior with their mobile phone cameras. Sequences like this encourage a viewership that swings back and forth between perceiving the actions of the character and perceiving the actions of the actor. Within the bounds of their youth, both Ja’mie and Jonah give Lilley license as a thirtysomething male actor to do and say things that, outside of the performance context, might get him a visit from the Australian Federal Police. Lilley’s knowing professional transgressions are wrapped up in Jonah’s compulsive and Ja’mie’s unwitting comic rule-breaking. These moments connect with contemporary Western fears about children, teenagers and sexuality, and show that behaviours read as naughtiness, naivety or idiocy in minors are cast as a more malevolent deviance in those over the age of eighteen.

Clearly, for those who called for Summer Heights High to be censored, there can never be any permissive comic context for the airing of topics like paedophilia or drug-overdosing teens. However, the ABC allowed it to go to air, and it was applauded by most television critics in the country. Those of us who do laugh at these moments laugh not just at the characters as rule-breakers and disruptive forces in the school community (who in the end, for different reasons, leave that community: Jonah against his will, Ja’mie returning to her posh private school), but at Lilley’s wiliness in so closely skirting some of the biggest taboos of the contemporary cultural landscape. The significant gap in embodied identity between actor and character gives the rule-breaking a double edge, and hence a greater charge than it would otherwise have.

The broader, layered context in which Lilley’s performances and these characters operate are the mock-documentary frameworks of the two series, as well as the extratextual material circulating around them in the form of such things as reviews and press interviews.

New hybrid comedy and ‘comedy vérité’

Brett Mills’ and Sue Turnbull’s studies of television comedy since the mid 1990s have observed the evolution of new televisual forms, such as ‘new hybrid comedy’ and ‘comedy vérité’, both of which also encompass television mock-documentary.[12]Turnbull, op. cit. p.102; Brett Mills, ‘Comedy Verite: Contemporary Sitcom Form’, Screen, vol. 45, no. 1, Spring 2004. Lilley’s comedy can be seen as part of these newer categories, sitting alongside UK series like BBC hit The Office (2001–2003) and People Like Us (1999–2000), US series such as The Larry Sanders Show (1992–1998) and Curb Your Enthusiasm (2000–), and Australian series like Frontline (1994–1997), The Games (1998–2000) and Kath & Kim, which first aired in 2002.

Unlike traditional sitcom form, with its static three-camera set-up, laugh track, and one-episode narrative arcs, new hybrid comedies tend to favour a single mobile camera, no laugh track, a faux- or quasi-improvisational performance style and, in some cases, an ongoing serialized narrative. These stylistic choices mean such shows tend to position their audiences differently from more traditional sitcoms. For a start, the lack of laugh track imposing a sense of collective agreement on what is funny means we have to take responsibility for our own laughter – what we laugh at and what it might reveal about us. A serialized narrative means that characters’ problems are not neatly resolved and closed off at the end of each episode. There is no pressure for events to return to equilibrium, and so stories and issues can unfold in surprising ways and often at a pace that is more true to life. Additionally, the more mock-documentary style programs like The Office and The Games are seen by some theorists as amounting to:

[a] questioning of the form and function of the documentary as a genre and its claims to represent an unmediated reality, but also to a dismantling of the distinction between the comedic and the serious.[13]Turnbull, ibid.

Not all hybrid comedies conform to the same pattern. For instance, Kath & Kim, while eschewing canned laughter and the static three-camera staging, remains otherwise tied to traditional sitcom through its episodic problem-of-the-week narrative structure and its ‘upbeat’ opening title sequence.[14]ibid. Moreover, after the first series, Kath (Jane Turner), Kim (Gina Riley) and Kel (Glenn Robbins) no longer acknowledge the camera’s presence or address the implied audience at home. We Can Be Heroes and (to a lesser extent) Summer Heights High, however, consistently appropriate documentary codes and conventions in mimicking the sort of expensive and somewhat conservative television documentary and docu-soap series familiar to regular ABC viewers. In both shows, characters digest off-screen events and rationalize their actions to the camera. Summer Heights High has no narrator, but We Can Be Heroes makes use of Jennifer Byrne’s cool, rational voice-over, with its journalistic connotations, to explain and link the scenes. Different character sequences are visually linked by zooming in on a map graphic of the continent, a pulsing light indicating the geographical location of the subject to follow. The incidental music is resolutely sober, and the camera is less a participant than an observer, although it is evident that the subjects’ behaviour is influenced by its presence and a desire to impress the implied audience.

Jane Roscoe and Craig Hight argue that all mock-documentaries to some degree contain a ‘latent critique’ of factual genres.[15]Jane Roscoe & Craig Hight, Faking It: Mock-documentary and the Subversion of Factuality, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2001, p.53. We Can Be Heroes could be read in this way as a parody of the limited depiction of and appeal to the ‘Australian people’ in federal government and corporate advertising. On occasion it could be read as simulating the flavour of the kinds of documentaries that fulfil the ABC’s charter of reflecting the nation back to itself, as well as shoring up a sense of identity against imported culture. Such latent critique can be found in the show’s pompous title sequence, with its smug parade of surf-lifesavers, farmers, cricketers and wildlife officers, looking, as one online commentator said, ‘like an ad for One Nation’.[16]Trakka, We Can Be Heroes thread on FasterLouder, 25 August 2005, <http://www.fasterlouder.com.au/forum/showthread.php?t=3563>, accessed 20 January 2008. A critique of factual genres is not, however, foregrounded throughout the program itself.

Documentary conventions as a comic and narrative frame

The primary function of the straight, consistent and sustained use of documentary conventions in both series is to comically and narratively frame the characters. The acknowledged camera presence and the implied extra-diegetic audience at home serve to amplify the social reach of the characters’ delusions about themselves.[17]Mills makes a similar argument about David Brent’s acknowledgement of the camera in The Office: Mills, op. cit., pp.71–2. So deluded are they that they are willing to declare their self-belief to the camera and the thousands of viewers beyond, rather than just within the program’s diegesis. Additionally, in interviews about We Can Be Heroes, Lilley, his director, Matt Saville, and producer, Laura Waters, have stated that the rationale behind the use of mock-documentary was to showcase Lilley’s talents in social mimicry by embedding his characters as much as possible in a believable social and media reality.[18]Nicole Brady, ‘Face Value’, The Age, 21 July 2005, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/tv–radio/face-value/2005/07/20/1121539006115.html>, accessed 20 January 2007. Saville has spoken of the series as ‘documenting’ the characters and their social worlds. This reality effect was attained in large part by having the entire support cast play roles that conformed to their actual social identity. Many of them untrained, the actors were instructed to ‘play it straight’, and to improvise around loosely written situations, with Lilley’s characters as the main catalyst in any given scene. Saville’s camera followed the characters around and documented their conversations and interactions.[19]Brady, ibid.; Quoted in Sigmatic, ‘Lilley of the Left Field’, Vibewire, youth media blog, 5 October 2005, <http://www.vibewire.net/3/node/3577>, accessed 20 June 2007.

The reality effect extends to Lilley’s performance of some of the characters, and their shift back and forth between being caricatures presented for ridicule and rounded, psychologically real figures of empathy.

The documentary realism also provides a counterpoint to Lilley’s gender drag and race-change performances – pulling them back from caricature. The reality effect extends to Lilley’s performance of some of the characters, and their shift back and forth between being caricatures presented for ridicule and rounded, psychologically real figures of empathy. In Summer Heights High, for instance, Jonah may be the source of much naughty mirth with his penis ‘dick*tation’ graffiti, homophobic insults, fighting and break-dancing, but he is also, surprisingly, the emotional core of the series. His tentative relationship with his remedial reading teacher, Mrs Palmer (Maude Davey), at Gumnut Cottage reveals vulnerability beneath his gruff swagger. According to online forum discussions, more than a few viewers were touched by a painful extended sequence in episode eight, as Jonah is carried bodily from the classroom, screaming and struggling like a desperate animal, after being expelled.[20]Several posters, ‘Summer Heights High – New Chris Lilley Comedy …’ thread, Vogue forums, <http://forums.vogue.com.au/showthread.php?t=263578&page=86>, accessed 21 January 2007. Likewise, in We Can Be Heroes, daggy, middle-aged Pat with her dolphin figurine collection and her loving, shaggy-haired husband, Terry, shifts the series into quiet tragedy when she stoically breaks the news of her liver cancer, later passing away before she can roll to Uluru. As O’Hara notes, ‘the gaze that laughs at folly is also sympathetic to these characters’ human foibles and the final episodes are quite dark and poignant.’[21]O’Hara, op. cit.

‘I forget I’m Chinese’

One of the strangest of these moments is where sadness and laughter clash, simultaneously building empathy for a character while reflexively drawing attention to issues of performance and representation. Towards the end of We Can Be Heroes, Ricky’s dad has forbidden him to quit his PhD in physics and follow his dream of becoming an actor. Ricky sits on his bed. The camera films him tentatively from just outside the open door, not wanting to intrude too much on this poignant and reflective moment. Recounting his father’s words half to the camera, half to himself, he says, ‘My father says I am Chinese, and there are not many roles in Australia for Chinese people.’ Ricky nods despondently and stares off into space, ‘And, sometimes I forget I’m Chinese,’ he says softly, his voice breaking with disappointment and hurt.[22]According to Brady, this line is often quoted to Lilley in the street by white fans of the series. We subsequently see him through the slightly open door lying on his bed weeping into his pillow. This moment, this pause in the ridicule, is one that seems to encourage compassion for Ricky’s plight and position as a non-white immigrant and an aspiring actor in Australian culture. Yet, at the level of casting and performance the moment is deeply ironic. Empathy for Ricky is almost immediately undercut by the reminder of the gap between Ricky’s identity and situation and that of the man who plays him – Lilley’s whiteness and comparative success in getting his face on television.

Such moments suggest that as much as they are ‘about’ anything, Lilley’s comedies are about performance and representation.

On the most immediate comedic level, both shows invite us to laugh at characters’ self-belief in their outmoded, inept or too-earnest performance. Some of the funniest moments are when characters are publicly performing: Mr G. in Summer Heights High, hips wiggling and hands outstretched towards his audience, basking in the glow of his own ego, singing his dreadful self-penned and self-aggrandizing songs; Ja’mie, in both series, coquettishly pouting and flouncing around the school auditorium with her music video dance moves; and all of Ricky’s amateur theatre performances, from his hammy audition speech to the crude pantomime of Aboriginality in the unwitting travesty that is Indigeridoo.

Professional transgression versus comic ineptitude

In contrast, think of how Lilley himself is portrayed as a performer in the promotional material, interviews and reviews circulating around his work. As we have seen above, so much of it emphasizes Lilley’s cleverness, his talent for ‘social mimicry’, his professionalism, his use of research, interviews and observation in developing his characters. Unlike David Walliams and Matt Lucas’ use of transfiguring hair and makeup for their sketches in 2003’s Little Britain, Lilley’s characters in We Can Be Heroes require only a wig and clothing supporting his plain facial features, and rely more exclusively on nuances of speech and gesture. Waters has said of him:

He has a bottomless pit of curiosity about people – about how people behave, everything from the bigger character traits to just tiny things about how somebody might pronounce something or the way they move their body.[23]Brady, op. cit.

Reportedly Lilley spent months immersed in particular social milieus, video-taping and interviewing the kinds of social types he would be playing: teenaged girls, middle-aged women, Chinese students, etc. In Ricky’s scenes, Lilley is often filmed surrounded by a large group of Asian students who treat him as one of the group, and whose responses to him work to affirm the authenticity of his performance. Implicitly, we are invited to contrast Lilley’s research and preparation with the way Mr G. or Ricky Wong prepare for their embarrassingly bad and ill-conceived forays into performance and the representation of others with little or no power. In one review, for instance, Vicki Englund notes the queasy response the series has been getting from some reviewers for the character of Ricky, before saying:

Lilley is much smarter than that … in the August 10 episode, Ricky is guilty of his own cultural insensitivity when we see him in his Chinese Musical Theatre Group rehearsing for their musical called Didgeridoo [sic].[24]Englund, op. cit.

While Lilley does not disguise his Caucasian facial features with makeup and prosthetics, Ricky and his friends wear shaggy wigs, loincloths and brown Lycra bodysuits while brandishing spears and boomerangs. If Lilley’s performance strives to give a sense of his characters’ ethnic identity, via a focus on the details of accent, gesture and cultural practice, Ricky’s wears the crude biological markers of race. If Lilley’s performances are based on close observation and months of interviews and research, Ricky tells us proudly that he researches Aborigines ‘from the Internet’ (rather than through consultation with actual Indigenous people such as representatives from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander centre at the university). The musical director, Chun, creates a didgeridoo-like sound on his synthesizer to accompany Ricky’s pretence at blowing through a painted tube. The stagehands simulate ancient Indigenous ‘hand’ painting by spray-painting around cardboard hand-shaped stencils. The dance sequences, in imitation of ‘black boy’ garden statues popular in 1950s suburban Australia, involve standing and jumping on one leg with a foot resting on the opposite knee. Gesture, when Ricky incorporates it into his performance, is not observed and mimicked from actual people, but reconstituted from white representations that belong to an earlier decade.

‘We had a million Aboriginal advisers coming in – it was ridiculous!’[25]Lilley quoted in Sigmatic, op. cit.

The series marks this rule-breaking. Ricky tells us that the Aboriginal Studies Centre at the university has forced them to make some production changes. They have had to cut the ‘Stolen Generations’ number, and are now wearing brown Lycra bodysuits rather than using black body paint. Later, during opening night, while the brown Lycra-clad actors on stage leap about to ‘Aborigine-me, Aborigine-you, we’re not just the people who eat kangaroo’, the camera keeps turning to register the stony-faced reactions of an Aboriginal couple from the Centre sitting in the audience of otherwise applauding, mainly Chinese families. Eventually we see them get up and leave, shaking their heads while everyone around them is oblivious to their disapproval.

Ricky’s happy obliviousness is again contrasted with Lilley’s awareness in interviews where he has voiced his frustration with the ABC’s rules on racial, especially Indigenous, representation. He has complained about the restrictions on what he could do in the Indigeridoo production, and evidences a kind of fierce pride at ‘getting away with it’, saying:

I thought, they’re the taboo things: you’re not allowed to impersonate an Asian person if you’re not Asian and you’re barely allowed to mention Aboriginal people, certainly not impersonate them. And so I combined that to have a Chinese student dressing up as an Aboriginal person.[26]Lilley quoted in Romeo, op. cit.

In this way, a series of implicit contrasts are set up both inside and outside the text between Lilley’s professional, knowing transgressiveness and Ricky Wong’s amateur and unknowing ineptitude. This allows Lilley to ridicule Ricky’s blackface performance as regressive, outmoded and offensive, at the same time as styling his own performance of Ricky as contemporary, boundary-pushing and cutting-edge. When Mr G. is just as offensive and tactless, and oblivious to the pain caused by his school musicals with their songs about teenage sex and drug-taking, we see these as evidence of a fundamental character flaw – his odiousness.[27]Notably in Summer Heights High, Mr G. inherits Ricky’s mantle of offensive amateurism, acting as the worse-by-comparison performing counterpoint to Lilley’s own performance of Jonah the Tongan delinquent, which, echoing Ricky as ‘Walkabout Man’, relies in part on a shaggy wig and skin darkening makeup. But like Ja’mie and Jonah, Ricky provides Lilley with another mask – a permissive context in which he can produce a blackface performance of Aboriginality, by a character who, troublingly, is positioned as ‘not knowing any better’.

It is Ja’mie’s and Jonah’s youth that allow us to excuse their behaviour. If we excuse Ricky’s lack of awareness of the rules, is it because of his ethnicity? What assumptions do we have of Chinese Australians and their place in the Australian symbolic order that would allow this? I have no answers to these questions. The upshot though is that through Lilley’s trampling or circumvention of these rules in his multi-layered comedy, we are asked to reflect upon the rules themselves, how they apply differently across the social spectrum, and what our responses (chuckles, horror or indifference) to their transgression suggest about our values.

This article was refereed.

Endnotes

| 1 | ABC’s blog, OzTAM data for Summer Heights High, Throng, 25 October 2007, <http://www.throng.com.au/summer-heights-high>, accessed 20 January 2008. |

|---|---|

| 2 | AAP, ‘Hundreds Queue to Meet Ja’mie’, The Age, 26 October 2007, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/hundreds-queue-to-meet-jamie/2007/10/26/1192941329984.html>, accessed 30 May 2008. |

| 3 | Edmund Tadros, ‘Fury at ABC Skit Mocking Drug Death’, The Age, 21 September 2007; readers’ comments, ‘Chris Lilley Drug Death TV “Slur”’, The Daily Telegraph, 21 September 2007, <http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/comments/0,22058,22456495-5006009,00.html>; readers comments, ‘Are You Prepared For This?’, Herald Sun, 26 August 2007, <http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/comments/0,22023,22309508-5000117,00.html>. All sites accessed 20 January 2008. |

| 4 | ABC Annual Report 2005–06, p.76, <http://www.abc.net.au/corp/annual_reports/ar06/>, accessed 20 January 2008. |

| 5 | Chris Lilley quoted in Greg Hassel, ‘Local Heroes’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 2005. |

| 6 | Vicki Englund, ‘Wizards of Oz’, The Blurb: Your Source for Australian Arts and Entertainment, 2005, <http://www.theblurb.com.au/Issue56/WCBH.htm>, accessed 20 January 2008; Lilley interviewed by Don Romeo, ABC NewsRadio, 27 July 2005, transcript <http://standanddeliver.blogs.com/dombo/2005/07/pictures_of_lil.html>, accessed 20 January 2008. |

| 7 | Susan Purdie, Comedy: The Mastery of Discourse, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1993; Brett Mills, Television Sitcom, bfi Publishing, London, 2005, pp.135–55; Alan McKee, ‘“Superboong! ….” The Ambivalence of Comedy and Differing Histories of Race’, Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media and Culture, vol. 10, no. 2, 1996, pp.44–59. |

| 8 | Marguerite O’Hara, ‘School’s Out There: Summer Heights High’, Metro, no. 155, 2007, p.70. |

| 9 | Sue Turnbull, ‘Look at Moiye, Kimmie, Look at Moiye!: Kath and Kim and the Australian Comedy of Taste’, Media International Australia, no. 113, November 2004, pp.103–4. |

| 10 | Purdie, op. cit. |

| 11 | ibid., p.13. |

| 12 | Turnbull, op. cit. p.102; Brett Mills, ‘Comedy Verite: Contemporary Sitcom Form’, Screen, vol. 45, no. 1, Spring 2004. |

| 13 | Turnbull, ibid. |

| 14 | ibid. |

| 15 | Jane Roscoe & Craig Hight, Faking It: Mock-documentary and the Subversion of Factuality, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2001, p.53. |

| 16 | Trakka, We Can Be Heroes thread on FasterLouder, 25 August 2005, <http://www.fasterlouder.com.au/forum/showthread.php?t=3563>, accessed 20 January 2008. |

| 17 | Mills makes a similar argument about David Brent’s acknowledgement of the camera in The Office: Mills, op. cit., pp.71–2. |

| 18 | Nicole Brady, ‘Face Value’, The Age, 21 July 2005, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/tv–radio/face-value/2005/07/20/1121539006115.html>, accessed 20 January 2007. |

| 19 | Brady, ibid.; Quoted in Sigmatic, ‘Lilley of the Left Field’, Vibewire, youth media blog, 5 October 2005, <http://www.vibewire.net/3/node/3577>, accessed 20 June 2007. |

| 20 | Several posters, ‘Summer Heights High – New Chris Lilley Comedy …’ thread, Vogue forums, <http://forums.vogue.com.au/showthread.php?t=263578&page=86>, accessed 21 January 2007. |

| 21 | O’Hara, op. cit. |

| 22 | According to Brady, this line is often quoted to Lilley in the street by white fans of the series. |

| 23 | Brady, op. cit. |

| 24 | Englund, op. cit. |

| 25 | Lilley quoted in Sigmatic, op. cit. |

| 26 | Lilley quoted in Romeo, op. cit. |

| 27 | Notably in Summer Heights High, Mr G. inherits Ricky’s mantle of offensive amateurism, acting as the worse-by-comparison performing counterpoint to Lilley’s own performance of Jonah the Tongan delinquent, which, echoing Ricky as ‘Walkabout Man’, relies in part on a shaggy wig and skin darkening makeup. |