Charles Chauvel’s final film, Jedda, has become iconic within the history of Australian cinema. Released in 1955, during a period when ‘assimilation’ was becoming the widely held policy of states and the Commonwealth in relation to the Indigenous population,[1]Assimilation, which had been developing as a policy direction throughout the 1950s, was formalised at the 1961 Native Welfare Conference of Federal and State Ministers: ‘The policy of assimilation means that all Aborigines and part-Aborigines are expected to attain the same manner of living as other Australians and to live as members of a single Australian community, enjoying the same rights and privileges, accepting the same customs and influenced by the same beliefs as other Australians’; see Henry Reynolds, Aborigines and Settlers: The Australian Experience 1788–1939, Cassell Australia, Sydney, 1972, p. 175 Jedda grapples directly with the nation’s ongoing questions about how ‘Aboriginality’ might be defined and understood, and about what the future for Australia’s Indigenous inhabitants might look like. While very much an ideological product of its time, Jedda provides some surprising insights into complex cultural issues, while also presenting a narrative that revels in the particularities of Australia’s outback landscape. Moreover, Jedda can claim a number of firsts: it was the first film by an Australian director made in colour, the first to use Indigenous actors (and indeed non-professional actors in leading roles), the first film to make such striking use of outback landscapes, and the first Australian film to be invited to the Cannes Film Festival.

After an earlier period of working in Hollywood, Chauvel himself already had a significant reputation as a director, writer and producer, often in collaboration (both credited and uncredited) with his wife, Elsa. His many films include The Moth of Moonbi (1926) and Greenhide (1926), both from the silent era; In the Wake of the Bounty (1933); Heritage (1935); Uncivilised (1936); Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940); The Rats of Tobruk (1944); Sons of Matthew (1949); Australian Walkabout, a thirteen-episode BBC travel documentary; four wartime shorts; and a wartime documentary re-edited from Soviet material. His last film in a long career, Jedda embodied a number of Chauvel’s key interests and skills: it has a documentary-like interest in the specific geographical landscapes of the Australian outback, particularly the rocks, creatures and plains of the Northern Territory; it demonstrates a keen interest in the idea of Australia and Australianness, and wasn’t afraid to consider the ‘Aboriginal question’ within this context; and, in line with Chauvel’s experiences in Hollywood, the film displays a strong interest in building narrative trajectory, and in using genre conventions to help it do so. Jedda has become a landmark in Australian cinema, both cinematically and for its engagement with representations of Aboriginal people and issues as well as with the specificity of the remote Australian landscape.

The narrative of Jedda

Sarah (Betty Suttor) and Douglas McMann (George Simpson-Lyttle) live on ‘Mongala’, a remote cattle station in the Northern Territory. While Douglas is away with the cattle, their only child dies from illness and Sarah is beside herself. We see her on the pedal radio, requesting a permit to bury her baby, highlighting her isolation as well as her grief. Douglas returns with his boss drover, Felix Romeo (Wason Byers), bringing with him a newborn Aboriginal child, whose mother has died ‘on the track’. Never considering leaving the child with her bereft father, Booloo (uncredited), Douglas asks Sarah to find a home for the ‘orphaned’ girl among the local Aboriginal population. Instead, Sarah decides – against Douglas’ inclinations – to keep the child herself, naming her, on the suggestion of her Aboriginal domestic servants, Jedda (which means ‘little wild goose’).

Sarah raises Jedda as her own, keeping her away from the ‘dirty piccaninnies’ and instead inculcating the girl with white customs. The young Jedda (Margaret Dingle) learns to speak English, to play the piano and to wear clean white clothes; she plays with Joe (Willie Farrar), an older, half-caste boy on the station, and watches, bemused and fascinated, when the local Aboriginal people head off on their seasonal walkabout. As Jedda (now played by Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, credited as Ngarla Kunoth) grows older, despite increasingly feeling the indeterminate call of her Aboriginal heritage, both Douglas and Sarah anticipate that she will marry Joe (now played by Paul Clarke, credited as Paul Reynall), who has evolved into a kind of second-in-charge to Douglas on the station. Such a marriage would work to keep both of them close to the homestead, thereby pleasing quasi-parents Sarah and Douglas, and also, through their role as ‘shadow couple’, reinforcing the hierarchy of ‘benevolent racism’ as practised at Mongala.

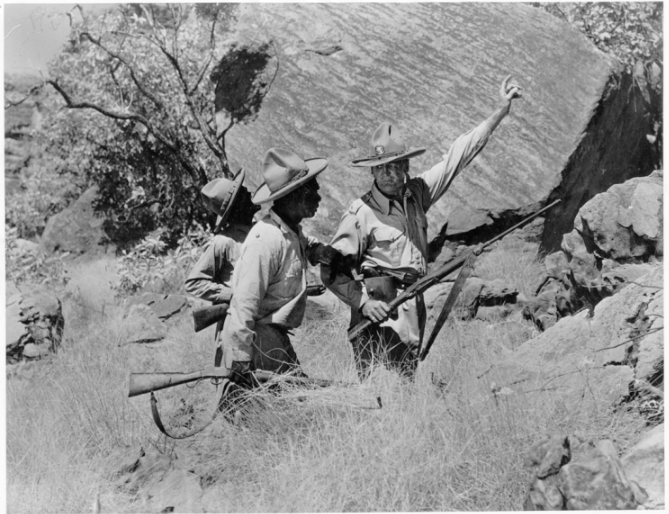

However, these plans come undone when a new Aboriginal man, Marbuck (Robert Tudawali), joins the seasonal workers. Described by police officer Tas Fitzer (Peter Wallis) as an outlaw, Marbuck is coded by the film as ‘wild’ – he wears a loincloth and proudly flaunts both his traditional background and his overt physicality and sexuality. Significantly, Marbuck is represented in the narrative as a dangerous and a seductive independent agent, and also as someone who operates across, but never truly within, both white and Indigenous cultures. And because he embodies all of her adolescent longings for cultural connection as well as romance, Jedda becomes entranced with him, finally following him out into the night and responding to his attempts to ‘sing’ her to his campfire. However, her tentative curiosity is soon overwhelmed by his violent action, epitomising the film’s ambivalent representation of Marbuck as both a cultural and sexual object of desire for the teenage Jedda, and as a violent and ultimately insane predator who steals Jedda away from the only family she has ever known. Jedda is kidnapped by Marbuck, and her incipient agency is thus fatally curtailed. This event initiates the second phase of the film’s narrative: an action-filled chase for Jedda and Marbuck, headed by Joe, who is desperate to retrieve the girl he loves.

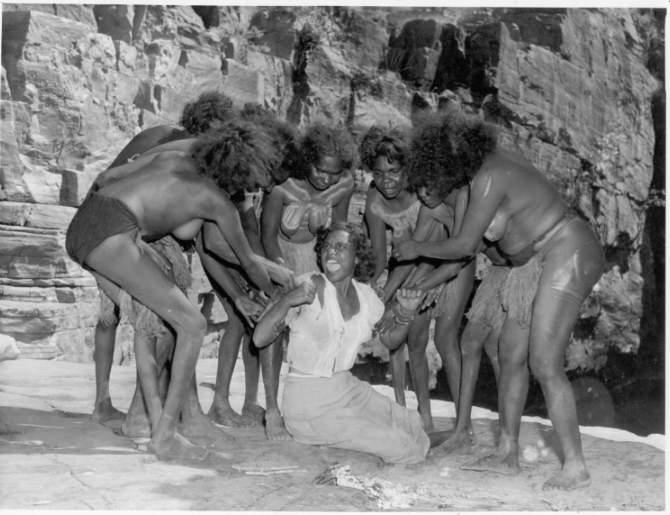

In Jedda, the Chauvels were looking for a ‘type’ of Aboriginality that conformed to notions of conventional feminine passivity, could operate as the eroticised object of the film gaze, yet confirmed an ideological link between Aboriginality and the primitive.

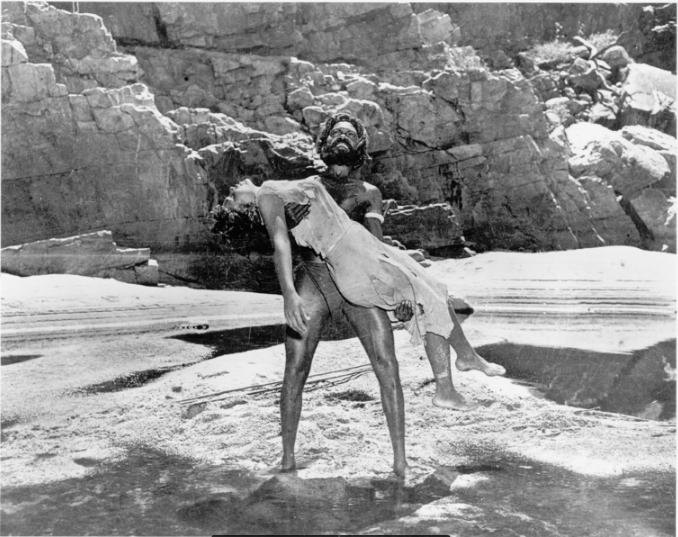

At first, Marbuck takes Jedda to his own tribe; however, they are appalled that he has taken a woman from the wrong skin group and curse him away from them. Excommunicated from his society as well as from the pastoral world of the white settlers, Marbuck is pushed to a psychological brink, becoming increasingly agitated and unstable. Meanwhile, as the pair find shelter in a cave overnight, it is implied that he sexually assaults Jedda while she is in a state of traumatised and/or manipulated stupor. The distraught girl, her clothes now in rags and her body increasingly exposed, is dragged across a variety of beautiful and harsh landscapes by an ever more erratic Marbuck – both of them now unable to return to their original homes or to find any viable alternative. Finally, the pair are located on a cliff, whereupon, despite Joe’s anguished appeals, Marbuck takes Jedda over the edge with him and they plunge to their deaths. The final voiceover by Joe – curiously spoken with an English accent – laments Jedda’s passing and narrates the incorporation of the ‘little wild goose’ into the mythic realms of the Dreamtime.

Production history

As the influential film critic Stuart Cunningham describes it, the production history of Jedda exemplifies ‘a reversal of the standard sequencing of pre-production (actor(s) (if star vehicle) -> story and character -> locations)’.[2]Stuart Cunningham, ‘Charles Chauvel: The Last Decade’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, p. 33. Indeed, the Chauvels’ approach to the making of the film seems to have begun with the very broad specificities of place, from which they worked backwards to find a story and, lastly, locate the people to act it out. As part of an extensive and well-orchestrated media campaign, Chauvel commented in a 1950 piece in The Sydney Morning Herald that he had been exhorted by a Hollywood producer to ‘go back home to Australia and get into the field […] Don’t be afraid to let that great country of yours become your star.’[3]The producer in question is Merian C Cooper; see Charles Chauvel, ‘Our Outback Is a Rich Field for Film Makers’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1950, p. 2. With such advice in mind, the Chauvels travelled to the Northern Territory that year, immersing themselves in vistas of spectacular rocks and rivers, floods, blistered plains, and cattle – as well as what Chauvel described as the ‘exotic native mixings’[4]Charles Chauvel, ‘Darwin’s Glamour Is Where You Find It’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September 1950, p. 11. that intrigued them – all the while searching for a story that might emerge almost organically out of their perceptions and experiences of place. As he noted in The Argus in 1951, the film was initially entitled the generic ‘The Northern Territory Story’: ‘I decided to produce a Northern Territory color film after my wife and I toured 8,000 miles of its vastness last year.’[5]Charles Chauvel, quoted in ‘Stark Color Film to Be “Shot” in N.T.’, The Argus, 19 June 1951, p. 3.

The end credits suggest that the narrative of the film is based on fact. However, as Elsa described it, Jedda is, rather, an amalgam of a number of anecdotal stories heard around the campfire during the couple’s trek through the Territory – stories of a young mother on an isolated cattle station who loses her child; of an Aboriginal girl raised by a white family but who nevertheless ‘ran off’ to join an Aboriginal tribe; and, finally, of ‘the able killer, Nemarluk. Ruthless and cunning, he was responsible for a number of murders and specialized in the abduction of attractive black women from station properties.’[6]Elsa Chauvel, quoted in Jane Mills, Jedda, Currency Press, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, p. 24. Quoting her husband, Elsa revealed:

These stories were adapted and interwoven to create the dramatic saga of Jedda, a girl of the Arunta tribe, who is caught up between white conventions and her sense of tribal identity.[7]ibid.

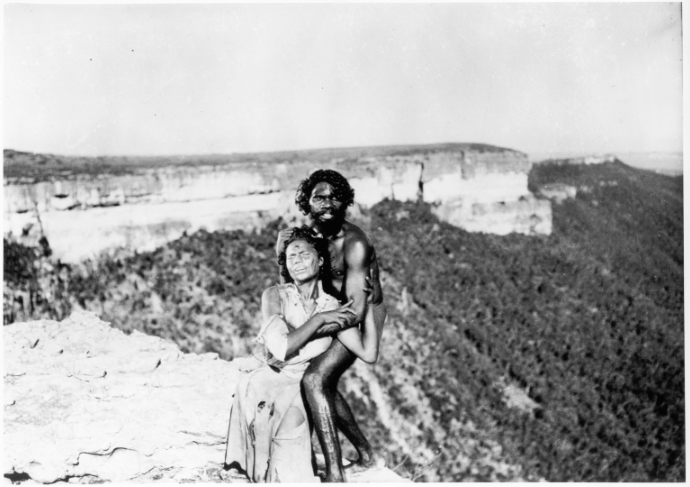

The combination of these elements provided everything the Chauvels were looking for: a poignant story (of a child lost, found, then lost again); the ability to track that story across the visually dramatic reaches of Northern Territory landscapes (although, ironically, the final scenes were shot in the Blue Mountains after film stock was lost in an accident), thereby indeed making this a story in which Australia as a place might be the ‘star’; a radical focus on the relationships between settler and Indigenous Australians, especially in the more remote areas little known to the moviegoing audiences of the cities; and plenty of drama and action, to be found in the narrative threads of romance, forbidden sexuality and the chase.

Although already a successful director, writer and producer, Chauvel struggled to put together the necessary finance to make the film; as Tom O’Regan has shown, Jedda was made during what was a ‘downturn in film production in the early 1950s’, which largely coincided with the advent of Robert Menzies’ government.[8]Tom O’Regan, ‘Australian Film in the 1950s’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, pp. 3–6. The director had turned down an offer of American financing because it had required the use of a Hollywood actress, rather than an Indigenous actor, in the title role;[9]‘Forever Amber – but Never Jedda Role’, The Courier-Mail, 13 September 1952, p. 1. Chauvel was also committed to taking the film on an expensive location shoot in the Northern Territory and to using the colour stock Gevacolor, which required overseas processing.[10]Cunningham, op. cit., p. 32. In addition, according to Cunningham, previous backers such as Greater Union were wary because of the cost overruns involved in Chauvel’s previous project, Sons of Matthew, and Universal – a formerly strong supporter – felt that the subject matter of Jedda was too ‘radical’ for commercial audiences.[11]ibid., p. 29. Literally banking on his own reputation, in 1951 Chauvel thus established a private company, Charles Chauvel Productions Ltd, building the necessary financial base largely through public subscription. Columbia Pictures, the film’s distributor, also provided post-production financing. In addition, Chauvel received some government backing; Cunningham cites the filmmaker’s ‘long-term lobbying for various governments’ support for the project together with his repeated invocation of [the film’s] national importance’. For the Chauvels, this was not just a private or commercial venture – they clearly saw Jedda (and marketed it) as a significant reflection on, and perhaps even creator of, an emergent Australian national culture. Twenty years before a new wave of Australian films (supported by direct funding from Gough Whitlam’s government) self-consciously made Australia’s history, landscape, narratives and people a primary cultural focus, Jedda also took seriously the stories of Australia’s people and places – albeit imbued with the values and perspectives of its own era.

Having found and woven together the threads for his film narrative, Chauvel then needed to find the right actors. While publicity material describes Rosalie Kunoth-Monks as coming from the ‘ancient Arunta tribe’, the shy and sheltered young woman who was to play Jedda was, in fact, attending school in Alice Springs when she was spotted by Elsa Chauvel. Having rejected a number of other potential aspirants on the grounds that they were ‘too inter-mixed and too far removed from the primitive that we were looking for’,[12]Elsa Chauvel, My Life with Charles Chauvel, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1973, p. 122. in Kunoth-Monks the Chauvels found ‘someone who could embody both primitive mystery and modern film star beauty’, as Karen Fox puts it.[13]Karen Fox, ‘Rosalie Kunoth-Monks and the Making of Jedda’, Aboriginal History, vol. 33, 2009, p. 79. Such a choice tells us a great deal about what Colin Johnson (now known as Mudrooroo Narogin) calls the ‘ideological position of Chauvel’. According to Johnson, in accordance with widely held views of his time,

Chauvel had ideas on what constituted a ‘true’ Aborigine, and this ‘trueness’ had little basis in reality, but in his holding such notions as the ‘noble savage’ – a stereotype familiar to us from Tarzan films.[14]Colin Johnson, ‘Chauvel and the Centring of the Aboriginal Male in Australian Film’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, p. 55.

In Jedda, the Chauvels were looking for a ‘type’ of Aboriginality that conformed to notions of conventional feminine passivity, could operate as the eroticised object of the film gaze, yet confirmed an ideological link between Aboriginality and the primitive; as Elsa noted, ‘the idea of the Northern Territory and its Stone Age men [… was] always playing hide and seek enticingly in Charles’ mind’.[15]Elsa Chauvel, op. cit., p. 116.

Jedda’s narrative attempts to have it both ways: first, as a romance adventure that, it was hoped, would appeal to mainstream audiences accustomed to the templates of classical Hollywood cinema; and, second, as an ‘authentic’ account of Aboriginal life as experienced in the ‘true’ milieu of the outback.

In an interview with The Australian Women’s Weekly in 1971 regarding her then-fostering of ‘part-Aboriginal children’, Kunoth-Monks explained that, as a fifteen-year-old girl raised first in a traditional Indigenous family and then in a Catholic school in Darwin, she had no idea about the way in which film worked to construct its stories: ‘I didn’t know what it was all about. I didn’t know what a film was.’[16]Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, quoted in Maureen Bang, ‘“Jedda” and Her Foster Family’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 June 1971, p. 3. Caught up by the charisma of the Chauvels – taken, almost like Jedda herself, under the mentoring and maternal wing of Elsa, who cared for her during the shoot and coached her in acting and speech – Kunoth-Monks was vulnerable to being shaped by the expectations and assumptions of white Australia, as embodied in the cinematic vision of the Chauvels. Not only was she required to wear additional dark make-up – fulfilling the mainstream expectation that literal blackness was linked with the authentic and the primitive – but even her first name was deemed not ‘Aboriginal enough’. Elsa’s decision to credit Kunoth-Monks as Ngarla, ‘her mother’s skin name’, was a source of great distress to the young actor because, as in the narrative of the film, it seemed to link her to the wrong marriage line or skin group.[17]Fox, op. cit., p. 81. While the Chauvels could acknowledge the ways in which Marbuck’s passion for Jedda broke his own tribe’s skin laws, and indeed used that knowledge as a crucial narrative device, they seemed unaware of or indifferent to the ways in which this renaming of their young star might compromise her within the traditions of her own community. Similarly, when Kunoth-Monks did finally see the entire film, and recognised the sexual inferences of her scene with Marbuck in the cave – achieved through post-production editing – she was appalled at the implications for her own reputation. Many years later, she commented that

according to her ‘grandmothers’ law’ she ‘was not to talk [to] or look at this strange man [Tudawali]’, but she was made to raise her head to do so, leaving her ‘ashamed’ because ‘[the Chauvels] slowly broke my law to make me act’.[18]Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, Message Stick interview, 18 February 2005, as cited in Fox, op. cit., p. 86.

The casting of Robert Tudawali, a Tiwi Islander, as Marbuck was also influenced by a similar desire to capture the ‘true primitive’, or at least the appearance of such. The Chauvels chose to credit the actor by that name rather than Bob Wilson, the moniker he had adopted while living in Darwin, to suggest a similarly direct access to a traditional Aboriginality. At the premiere of the film in Darwin, recounts Jane Mills, Tudawali chose to sit downstairs with the other segregated Aboriginal people – thereby exposing the contradictions at work within racialised social structures.[19]Mills, op. cit., p. 71. However, what might be interpreted as a strong political statement by Tudawali was followed by a tragic life truncated by alcohol and tuberculosis, and by a fundamental uncertainty about which side of the white/Indigenous divide he wanted to or could survive in. In this sense, like actors David Gulpilil and Tom E Lewis, Tudawali’s troubled life reflects so much of the ongoing experience of Indigenous masculinity within a dominant Anglo culture: a flickering of fame in the movies turns out not to be enough to reverse the long-term patterns of trauma caused by centuries of dispossession, loss of language and culture, and the shocking effects of the Stolen Generations.

Also highlighting the implicit dominance of whiteness is the casting of Paul Clarke (credited as Paul Reynall), an actor of Italian and not Indigenous descent, as Joe. A white man presented in theatrical blackface, Clarke plays a character who literally ‘mimics the white man’, in Dave Palmer and Garry Gillard’s words,[20]Dave Palmer & Garry Gillard, ‘Aborigines, Ambivalence, and Australian Film’, Metro, no. 134, 2002, p. 112. compliantly enacting his beliefs and behaviours. And, as Benjamin Miller argues persuasively, the use of blackface – made so prevalent with the minstrelsy performances of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – embodies ‘a fantasy that the other is complicit with white superiority and privilege’ and, as such, ‘secur[es] the fiction of terra nullius’.[21]Benjamin Miller, ‘The Mirror of Whiteness: Blackface in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, ‘Spectres, Screens, Shadows, Mirrors’ special issue, 2007, pp. 148, 149. Clarke plays the part of a ‘half-caste’ Indigenous man, but it doesn’t matter to Chauvel or to audiences that he is a white man in masquerade, as the half-caste is well on his way to ‘whiteness’ and the Indigenous is already being ‘written out’.

Nonetheless, that two non-professional Indigenous actors were cast in the film’s leading roles also reflects Chauvel’s ethnographic and documentary interests in Aboriginal history and contemporary experience. Jedda’s narrative attempts to have it both ways: first, as a romance adventure that, it was hoped, would appeal to mainstream audiences accustomed to the templates of classical Hollywood cinema; and, second, as an ‘authentic’ account of Aboriginal life as experienced in the ‘true’ milieu of the outback. Of the casting of Kunoth-Monks and Tudawali, Cunningham writes:

‘Native’ exotica, displayed salaciously and naively for the voyeuristic frisson of a fifties white audience? Yes, if it is equally said that Chauvel dramatises black experience with a force and centrality approached only by [Fred] Schepisi’s [The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978)] in the history of Australian feature filmmaking.[22]Cunningham, op. cit., p. 36.

In 1954, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that Jedda had cost £90,823 to make;[23]‘Chauvel Film Cost £90,823’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 December 1954, p. 9. in 1956, Charles Chauvel Productions, by then retitled as Jedda Productions, listed a profit of only £50,454 on the film: ‘Directors say the film “Jedda” was a success in Australia, but overseas results were disappointing.’[24]‘Jedda’s £50,454’, The Argus, 8 December 1956, p. 25. While not the initial blockbuster that the Chauvels must have been hoping for, Jedda has nevertheless emerged as a classic of Australian cinema. It has explicitly inspired at least two later films – Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990) and Baz Luhrmann’s Australia (2008). The latter’s strange and stylised blend of romance and western also centres on the question of whether a white couple should adopt an Aboriginal child, but the answer in Luhrmann’s film, ultimately, is no. In contrast, Moffatt’s film creates, in minimalist style, a fantasy scenario in which Jedda has survived and now cares for the elderly Sarah – thereby avoiding the earlier narrative trajectory of doom and failure and exploring the shifting power dynamic between the white woman and her Indigenous daughter.

Reception

Jedda was largely lauded by critics after its premiere at the Star Theatre in Darwin on 3 January 1955. In particular, critics focused positively on the representation of an ‘authentic’ Northern Territory landscape never before seen on film. As the Sydney Sun commented in its review entitled ‘Superb scenery in the film Jedda’: ‘The frightening escarpments of Ormiston Gorge and Stanley Chasm, with Ayers Rock and the Buffalo country of Mary River, are depicted in their natural beauty.’[25]‘Superb Scenery in Jedda’, The Sun, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. According to the ‘Salute to Jedda’ special in Film Weekly, the film was important due to its depictions of uniquely Australian landscapes and its (unusual) focus on Aboriginal characters; in this way, it offered cinema-goers something ‘completely different’, thereby ensuring its box-office success.[26]‘The Real Importance of Jedda (It’s Box Office … and It’s Australian)’, ‘Salute to Jedda’, Film Weekly, 14 April 1955, p. 1. In London, where it was released under the title of Jedda the Uncivilized, The Daily Telegraph noted that Jedda ‘could be the film to put Australia on the cinema map’.[27]‘Jedda Boost to Australia’, The Daily Telegraph, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. The Adelaide Advertiser noted on 5 January that Jedda ‘shows the world’s oldest race in one of the oldest countries, in which the white man has only begun the process of development and civilisation’.[28]‘Film Jedda Is Gripping’, The Advertiser, 5 January 1955, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. The review in The Australian was more ambivalent, congratulating Chauvel for his ‘standards of production’, but concerned that the ‘unlovely’ appearance of the ‘Australian aborigine in general’, and the stated fact that ‘Australians generally have little sentiment for their native Negro people’, would adversely affect box-office receipts, especially overseas.[29]‘Jedda’, The Australian, 15 June 1955, p. 6. In May of 1955, Film Weekly summed up that

Charles Chauvel has made a film which ennobles and dignifies the Australian north, and its native inhabitants. The color photography is at most times magnificent, often in its panoramas reaching beyond Hollywood standards. There’s some fine action, and the human story, very uneven in quality, is at best compelling.[30]‘Jedda’, Film Weekly, 12 May 1955, p. 13.

When considering Jedda as a historical artefact … we are engaging with the ideology behind what is now referred to as the Stolen Generations enacted in its historical moment.

More recent writers have both taken a longer view of the position of Jedda within Australian cinema, and also situated any reading of the film explicitly within the discourses of racism and colonialism that characterised Australia in the 1950s. In her 2012 study of the film, Jane Mills notes that, while the film strikes her as important in terms of an evolving Australian cinema and in the representation of the nation’s Indigenous inhabitants, she cannot ‘love’ it: ‘when I first saw it, I thought I had never before in my life seen a film so racist’.[31]Mills, op. cit., p. 13. Reviewing the film at the time of its release on DVD in 2004, Paul Kalina interrogates the racial politics of Jedda as well as offering a closer analysis of character and the ‘human story’:

While the film is not devoid of patronising stereotypes and some clunky dialogue, it is highly critical of the then-prevailing policy of assimilation. It boldly rejects the notion that indigenous Australians should conform to the expectations of European Australians.[32]Paul Kalina, ‘Chauvel’s Jedda Led the Way’, The Age, 15 December 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/Film/Chauvels-Jedda-led-the-way/2004/12/14/1102787061956.html>, accessed 9 March 2015.

Similarly, in his Curator’s Notes for australianscreen, Paul Byrnes reads Jedda less as a simple portrayal of Australian landscape and exotic lifestyle, and more as a nuanced exploration of gendered and racialised identities:

Jedda is a more mature film, in which the emotions of Jedda and Marbuck are given considerable weight. It’s probably fair to say that Chauvel was a man of his time, with a belief in the separation of the races and the primacy of ‘blood’ as the determiner of behaviour. It’s also true that he had an unusual degree of sympathy for, and interest in, Aboriginal culture.[33]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Jedda’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/jedda/notes/>, accessed 9 March 2015.

Indeed, contemporary critics continue to see Jedda as iconic in status and as influential in the development of an Australian cinema; they are also more focused on the film’s ambivalent and now-problematic portrayal of Aboriginality and its impact on the conflicted lives of the film’s main characters.

Structure and genre

Voiceover

The use of Joe as narrator, via voiceover both at the beginning and at the end of the film, serves a number of functions. Most obviously, it fulfils the conventional role of any voiceover to frame and manage a narrative that the audience might otherwise experience as either chaotic or too disturbing. By clearly bookending the story with a different register of narration, we understand where the story begins and ends, and are somewhat reassured by the film’s ability to contain it. By using Joe’s voice in narration, the film also provides us a with a particular point of view: we are to understand that the story is told from the perspective of the half-caste man who, while not central to the story, did love Jedda and, at least initially, lived a similar life to her. The improbable BBC tones of Joe’s narrator voice – which are at odds with his voice elsewhere in the film and, as Allison Craven notes, were achieved through the ‘aural blackface’ of post-production dubbing[34]Allison Craven, ‘Heritage Enigmatic: The Silence of the Dubbed in Jedda and The Irishman’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 28–30. – emphasise both his difference from Jedda and also, implicitly, his codification as white. Barbara Creed also notes these sometimes-jarring shifts, whereby Joe’s ‘voice speaks in many registers, reflecting the film’s contradictory positions on assimilation’.[35]Barbara Creed, ‘Jedda’, in Geoff Mayer & Keith Beattie (eds), The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand, Wallflower Press, London, 2007, p. 70.

While Joe is identified as the child of an Aboriginal mother and an Afghan father, Mills, like Colin Johnson, speculates on Joe’s parentage as indicative of what she describes as ‘an act of miscegenation that the film cannot discuss or represent’.[36]Mills, op. cit., pp. 67–8. Raised in an almost son-like way by Douglas, with every expectation of taking on a crucial role in the running of Mongala, Joe is nevertheless crucially not acknowledged as Douglas’ child, and is not admitted into the domestic interiors of the station; rather, he is kept in a liminal status – neither inside nor outside, ‘civilised’ nor ‘primitive’. The story of Jedda thus remains his to tell – because he loved her; because even for Chauvel it was not an important enough story to be told by someone entirely ‘white’; and also because, on a subliminal level, a similar act of violence and dispossession informs both Joe’s and Jedda’s life stories. However, as Karen Jennings discusses:

there are two Joes in Jedda – the diegetic character, Joe, whose dialogue and actions personify the perfectly assimilated ‘half-caste’, and the Joe of the (very cultivated) voice-over narration whose discourse veers strongly towards Doug McMann’s anti-assimilationist views.[37]Karen Jennings, Sites of Difference: Cinematic Representations of Aboriginality and Gender, Australian Film Institute, Research and Information Centre, South Melbourne, 1993, p. 29.

The voiceover also presents the story of Jedda as being contained in the past – with Joe, we look back with sadness as well as distance on the terrible events of her life, thus finding a degree of acceptance, especially by means of her story’s movement into the mythical. In this sense, the film’s structure asks us to pull back from identifying with a particular girl, and to understand her story as being emblematic of both the potential and the failure of Aboriginal people in general – a failure to integrate with white, Western culture, or to find any viable alternative. The strong sense of nostalgia and retrospection reinforced by the structural device of the voiceover also echoes early colonial and social Darwinist conceptions of the Aboriginal as an anachronism and, thus, as an inevitably ‘dying race’; from this point of view, despite the best efforts of Sarah, Douglas and Joe, Jedda cannot be ‘saved’ from the wildness within her Indigenous identity, and the best that can be done is to incorporate her into some kind of mythical eulogising. This excruciating and arrested narrative about Aboriginality clearly reflects much about a mid-twentieth-century discourse caught between racial essentialism and governmental policies of assimilation. Jedda is not simplistically racist in its understanding of Indigeneity, culture and identity; as Jennings argues, the film’s ‘distinctive impact derives from […] the complexity and ambivalence of the discourse it mobilizes around the issues of assimilation versus cultural maintenance’.[38]ibid., p. 33.

Narrative form

As a number of critics have noticed, Jedda is divided into (at least) two quite different narrative structures. Creed describes the film as having ‘two captivity narratives at work’: a ‘classic captivity narrative’, which ‘occurs when a white settler, usually a woman, is taken captive by indigenous people’, and a ‘reverse captivity narrative’, which transpires when ‘an indigenous woman (and sometimes a man) is taken captive by a dominant Caucasian culture’. In the case of Chauvel’s film, ‘Jedda is caught up in a reverse captivity narrative in relation to the McManns, and a classic captivity in relation to Marbuck.’[39]Creed, op. cit., p. 68.

The interweaving of captivity narratives emblematises the film’s profound ambivalence and uncertainty regarding the ‘nature’ of Aboriginality and the more productive, and even ethical, way to imagine interactions between the categories of ‘white’ and ‘black’. What indeed, we might ask, are we to identify as the central ‘theft’ within the narrative? Is it Douglas’ unquestioned assumption that the baby whose mother had just died would be better off if he took charge of her? Or is it Sarah’s patronising but well-intentioned desire to make Jedda just like her own daughter – ‘as if she were white’ – thereby excluding her from any interactions with her Indigenous family and customs? Or is it embodied by Marbuck, as an ‘untamed’ black, whose sexual theft of Jedda disrupted what would have otherwise been a harmonious assimilation? Or does the problem lie with Jedda herself, as emblematic of the ‘Aboriginal question’, whose desire for traditional experience and for Marbuck are what lead her away from the sanctuary of the homestead and into the dangers of ‘the bush’?

The film certainly shifts its emphasis and style at the point where Jedda is taken by Marbuck. The first half of the film can be seen more as a melodrama; situated predominantly within the interior domestic sphere, the narrative deals with the intimate relationships within the family – here, primarily between Sarah and Jedda or Jedda and Joe. The tone of the initial voiceover indicates that this domestic arena is fragile, however, and this is reinforced by Jedda’s own yearnings, which disrupt her progress as Sarah’s ‘white child’. Uninterested in a proposed shopping trip to Darwin, Jedda looks longingly after those heading out on walkabout; or, playing a classical piece on the piano, Jedda is tormented by thoughts that morph the Western music into the sounds of the didgeridoo and the drums, displacing the ostensibly ‘taming’ effects of white culture. As Mills illuminates, in a moment of melodramatic excess the ‘Earthy, “native” rhythms and tribal songs disrupt the classical western music’; this is reinforced by the mise en scène in which the ‘camera zooms in on tribal war artefacts (spears and shields) hanging on the wall, their asymmetrical patterns contrasting with the straight lines formed by the piano keys’.[40]Mills, op. cit., p. 38.

The second section of the film becomes much more focused on the chase and, in this sense, it particularly echoes the genre of the western. In a manner similar to John Ford’s captivity western The Searchers (released a year later, in 1956), the event of the kidnap leads to a linear series of events as Jedda is hauled across a range of landscapes and pursued by her would-be rescuers. Instead of the mesas and buttes of Monument Valley – Ford’s signature landscape – Chauvel uses the dramatic cliffs and ravines of the Northern Territory almost like characters in the drama, thereby giving the events of the narrative a heightened degree of intensity. However, unlike The Searchers, whose title suggests that the emphasis is clearly on the experience of those who pursue and their reaction to the ‘compromised’ status of those who are ‘saved’, Chauvel keeps our attention firmly on Jedda and Marbuck and on their increasingly manic and directionless movements. We know that Joe and his diminishing band of supporters (they are incrementally lost to the dangers of the outback) are following the pair – which lends plausibility to our knowledge of events in what is technically a first-person narrative – but, in comparison to Marbuck’s energy and virility and Jedda’s passionate emotions and suffering, Joe seems an ineffectual character, somehow emasculated by his allegiance to white customs, clothes and speech patterns. In an interesting twist, it is Joe who does survive and who goes on to narrate this story to us. Although lacking the excitement of characters such as Marbuck and Jedda, he does represent the kind of diminished and tamed version of Aboriginality that can be tolerated by a dominant Anglo-centric culture.

Jedda can also be seen as something of a romance manqué. The lingering shots of Joe and Jedda on horseback, or lying on the picnic rug and talking, and the confused and longing glances that Jedda initially gives Marbuck – all of these might suggest a focus on the emotional intensity and complex interactions of the romantic pairing. However, given the events of the narrative, romance is only ever used as a narrative driver paradoxically within the film. The romance genre requires characters to have enough autonomy and subject formation for their emotional lives to take centre stage within the narrative; freighted with the era’s ideological baggage regarding notions of femininity, Indigeneity and racial hierarchisation, the possible pairings of Jedda–Joe and Jedda–Marbuck remain pawns in an ideological debate about the relationship between white and Aboriginal Australia.

Key themes

Indigeneity

The 1950s saw the entrenchment of policies of assimilation in relation to the Indigenous population, who were not, at this point, citizens of Australia. The assumption was that, the more ‘white’ was ‘in’ an Indigenous person, the more possible it would be for that person to adapt to Western culture. This notion that genetic or racially defined identity was a determiner of the capacity to be civilised then led to the moral obligation to remove part-Aboriginal children from their Indigenous families and ‘transplant’ them into some arena of white society. To Creed, these concepts and policies of assimilation also operated within a wider postwar environment, in which ‘the West was experiencing the social and political consequences of centuries of imperial rule, slavery and colonial empire-building’.[41]Creed, op. cit., p. 67. Even though Nazi eugenics had taken notions of the supremacy of a ‘pure whiteness’ to horrific extremes only ten years earlier, it is important to remember that such binaristic ideologies that privileged whiteness over blackness, and the so-called civilised over the primitive, were in fact the widely shared legacies of post-Enlightenment imperialism. Jedda reflects this legacy in the implied assumption that the McManns – and the Anglo systems for managing land, family and economy that they represent – are inherently superior to Jedda’s own people. However, despite this backdrop of racialised thinking, the film does take some steps towards making Indigenous people and issues the main focus of the film – a radical position in 1955.

As well as the main narrative device of identification with the central character of Jedda, the film reproduces the key debates of the day regarding how to think about and treat Aboriginal people. We see these debates explicitly enacted through the positions of Douglas and Sarah McMann, as they argue over their role in relation to Jedda. Were Aboriginal people indeed a ‘dying race’, and thus just required ‘shepherding out’, sympathetically or otherwise? Was Aboriginality immutable, as Douglas’ cultural essentialism maintains, meaning that any efforts to ‘civilise’ Jedda will necessarily fail? Or, as Sarah vehemently holds, is it possible that ‘these people’ might be educated in order to be assimilated into a superior white society? Can the Aboriginal person be ‘redeemed’ by the benevolent intervention of white society? As Catherine Kevin has argued, this debate, as dramatised by the McManns within the private sphere of their kitchen, functions to ‘remind [today’s] audiences of the broader historical context of race-science and child-removal that produced this film’.[42]Catherine Kevin, ‘Solving the “Problem” of the Motherless Indigenous Child in Jedda and Australia: White Maternal Desire in the Australian Epic Before and After Bringing Them Home’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 4, no. 2, 2010, p. 147. In other words, when considering Jedda as a historical artefact, as Kevin suggests, we are engaging with the ideology behind what is now referred to as the Stolen Generations enacted in its historical moment. No, Jedda was not kidnapped from her family – a narrative explored in Phillip Noyce’s Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002) – but she was re-homed with the McManns in the explicit understanding that it was the beneficial and thus preferred outcome for her, and would always outweigh the benefits of staying within her original family and community. However, because of its complex narrative threads, the film doesn’t unequivocally support this view of assimilation, giving some weight to Doug’s belief that Jedda needed to know and experience elements of traditional culture – perhaps with a view to either being reabsorbed into the ‘primitive’, or potentially being in a position to more actively and knowingly choose a path on her own.

Like much contemporary theorising about race, Jedda found itself in deep and confusing waters in relation to the concept of Aboriginality. As the events of the narrative seem to suggest, ‘Aboriginal’ is not a static identity; rather, it is influenced (not surprisingly) by a variety of factors such as environment, family, education, personality and circumstance. While this nuance somewhat plays out in the film through the use of terms such as half-caste, full-blood, tribal, station black, etc., these ‘gradations’ of blackness foreground the inherent difficulty in privileging the construction of race or ‘blood’ as the key determiner of identity.

Gender

The character of Jedda is marked by the two problematic discourses (at least in 1955) of Aboriginality and femininity. The stereotypes associated with these two categories of identity dovetail in the passivity and compliance – indeed, gratitude – that are expected of her as the privileged ‘white daughter’ of the McManns. Her growing discomfort in such a role is presented by the film as failures of both femininity and ethnicity. The ‘blood call [that] summons her back to her tribe’[43]‘Forever Amber – but Never Jedda Role’, op. cit. suggests a racial essentialism that no amount of ‘nurture’ could eradicate or tame, while Jedda’s incipiently sexual longings for Marbuck also place her in the age-old category of Eve, whereby women’s sexual curiosity and disobedience lead to trouble for themselves and others. In this sense, Jedda’s ultimately tragic fate can be read as a punishment for these impulses to be active and curious and to stray outside the confines of the white domestic interiors – perhaps even for taking seriously Sarah’s offer that, at least under her auspices, Jedda could act with agency, ‘like a white girl’.

As I have discussed elsewhere, while Sarah is a dutiful daughter of patriarchy in her role as homemaker and support to her husband, she also demonstrates a wilfulness in taking on Jedda that is ultimately punished in her implied suffering at the loss of a second child.[44]Rose Lucas, ‘Original Sins: Imaging Maternity in Australian Cinema’, Meridian, vol. 18, no. 2, 2002, pp. 243–65. Not only is Sarah determined to raise Jedda as her own, believing strongly in the power of her nurture to ‘create’ a white girl in Jedda, but she refuses any further sexual contact with Douglas as well – ‘Never again,’ she tells him, unwilling to take the emotional risks of another pregnancy. Such defiance against the compliant role of wife, coupled with what is coded as the excessiveness of her grief for her lost child, renders her a suspect figure in the narrative, aligning her more closely than she would have realised with the incipient independence of Jedda herself.

A tangle of gendered and racialised roles are further explored through the contrasting romantic ties between Jedda and Joe, and Jedda and Marbuck. Although, in many senses, Jedda’s relationship with Joe makes sense in terms of her life on the station and her incorporation into the McManns’ way of life, it is depicted as insipid, more informed by the affections of familial obligation (given they are both quasi-children of the McManns) than by sexual or romantic passion. Joe also represents the ‘colonised’ position of acquiescence to the superiority of Western culture: he is the half-caste who is well on his way to ‘passing’ as white, and thus offers Jedda ongoing access to white culture via the ‘dilution’ of his Aboriginality. Jedda’s connection with Marbuck, on the other hand, although volatile and ultimately exploitative and fatal, elicits a passion that awakens both her sexuality and her desires to connect with her traditional culture. In many ways, Jedda and Marbuck play out a version of what Johnson has referred to as the Tarzan–Jane syndrome, although here no sustainable middle ground is found between the categories of wildness and civilisation. Similarly, Jedda and Marbuck echo the Beauty and the Beast trope, whereby the beautiful girl is attracted to the wild and dangerous – yet ultimately seductive – masculine. However, unlike in these stories, Jedda doesn’t get the chance to understand, let alone love, her ‘beast’, or to draw him at least halfway back into the taming confines of social regulation. Instead, hampered by the binarised expectations of both ‘white’ and ‘black’ identities, they are herded over a literal as well as a figurative precipice together, with nowhere further to run.

Landscape

The wild and beautiful landscapes of the Northern Territory operate both as a kind of dramatis personae within the narrative and as a backdrop to the action. Coolibah Station, situated along the Victoria River and a six-hour drive from Darwin, provides the setting for Mongala Station in the film. Between Darwin and Kakadu is the Mary River at Marrakai, where Jedda is abducted by Marbuck, ‘an area with saltwater crocodiles, freshwater billabongs, floodplains, woodlands, and paperbark and monsoon forests’.[45]Mills, op. cit., p. 5. As suggested earlier, the Chauvels have immersed themselves in landscape first, then found a story to match it – a story in which the harshness and grandeur of place is crucially aligned with the racialised identities and experiences of the characters. Cunningham uses the term ‘locationism’ to refer to Chauvel’s practice – a practice that both highlights the visual specificity of the Australian landscape (perhaps with both local and overseas audiences in mind), and links the notion of Aboriginality to scenes of remoteness and the primitive. Describing the second phase of the film, in which the surprisingly ‘slow-paced’ chase takes place, Cunningham examines the flight of Jedda and Marbuck as ‘constantly placed within locationist showcasing of scenic grandeur: the dramatized spectacle of racial alterity thus doubled by the documentarist spectacle of topographical alterity’.[46]Cunningham, op. cit., p. 36. This use of spectacle not only adds to the narrative’s intensity, creating epic effects that extend the story beyond the sphere of the individual protagonists, but it also simultaneously objectifies and even fetishises both the idea of the ‘outback’ and that of Indigeneity.

Conclusion

In 1955, the figure of the young Indigenous woman Jedda was literally backed into an impossible corner. Part of a spectrum of social engineering that we would now refer to as the Stolen Generations, Jedda was severed from her family and background and assimilated into a white family and its values – only to be violently ‘stolen’ back into what is represented as a dead-end Aboriginality associated with wildness and the primitive, which left her socially and sexually alienated from both white and Indigenous societies. On one level, Jedda would thus appear to be a film about the difficult and conflicted experience of being Indigenous in a colonised Australia. However, literally framed by the discourses and debates of assimilation, it is primarily a film about white attitudes and values – white attitudes to questions of race, Indigeneity, gender and a cultural politics of place. Jedda, together with her personal issues, is the largely passive object of the film’s dominant white gaze, her individual tragedy only a passing backdrop for the film’s exploration of the ‘Aboriginal problem’.

This article has been refereed

Select bibliography

Charles Chauvel, ‘Our Outback Is a Rich Field for Film Makers’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1950, p. 2.

Elsa Chauvel, My Life with Charles Chauvel, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1973.

Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, Charles & Elsa Chauvel: Movie Pioneers, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1989.

Allison Craven, ‘Heritage Enigmatic: The Silence of the Dubbed in Jedda and The Irishman’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 23–34.

Barbara Creed, ‘Jedda’, in Geoff Mayer & Keith Beattie (eds), The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand, Wallflower Press, London, 2007, pp. 63–72.

Stuart Cunningham, ‘Charles Chauvel: The Last Decade’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, pp. 26–46.

Stuart Cunningham, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991.

Karen Fox, ‘Rosalie Kunoth-Monks and the Making of Jedda’, Aboriginal History, vol. 33, 2009, pp. 77–95.

Anne Hickling-Hudson, ‘White Constructions of Black Identity in Australian Films About Aborigines’, Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 4, 1990, pp. 263-74.

Karen Jennings, Sites of Difference: Cinematic Representations of Aboriginality and Gender, Australian Film Institute, Research and Information Centre, South Melbourne, 1993.

Colin Johnson, ‘Chauvel and the Centring of the Aboriginal Male in Australian Film’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, pp. 47–56.

Catherine Kevin, ‘Solving the “Problem” of the Motherless Indigenous Child in Jedda and Australia: White Maternal Desire in the Australian Epic Before and After Bringing Them Home’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 4, no. 2, 2010, pp. 145–57.

Marcia Langton, ‘Out from the Shadows’, Meanjin, vol. 65, no. 1, 2006, pp. 55–64.

Marcia Langton, ‘Well, I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and About Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993, available at <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au:443/getmedia/580b7762-ceb4-4b3f-abad-7ec91b4e6adf/WellIHeard.pdf>, accessed 9 March 2015.

Rose Lucas, ‘Original Sins: Imaging Maternity in Australian Cinema’, Meridian, vol. 18, no. 2, 2002, pp. 243–65.

Benjamin Miller, ‘The Mirror of Whiteness: Blackface in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, ‘Spectres, Screens, Shadows, Mirrors’ special issue, 2007, pp. 140–56.

Jane Mills, Jedda, Currency Press, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012.

Catriona Moore & Stephen Muecke, ‘Racism and the Representation of Aborigines in Film’, Australian Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 1984, pp. 36–53.

Tom O’Regan, ‘Australian Film in the 1950s’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, pp. 1–25.

Dave Palmer & Garry Gillard, ‘Aborigines, Ambivalence, and Australian Film’, Metro, no. 134, 2002, pp. 110–6.

Suneeti Rekhari, ‘The “Other” in Film: Exclusion of Aboriginal Identity from Australian Cinema’, Visual Anthropology, vol. 21, no. 2, 2008, pp. 125–35.

Graeme Turner, ‘Breaking the Frame: The Representation of Aborigines in Australian Film’, in Anna Rutherford (ed.), Aboriginal Culture Today, Dangaroo Press, Sydney, 1988, pp. 135–45.

CREDITS AND KEY CREW

Year of Release 1955 Production Company Charles Chauvel Productions Running Time 101 minutes Director/Producer Charles Chauvel Screenplay Charles Chauvel, Elsa Chauvel Director of Photography Carl Kayser Special Photography Eric Porter Dialogue Direction Elsa Chauvel Editors Alex Ezard, Jack Gardiner, Pam Bosworth Sound Arthur Browne Assistant Director Philip Pike Unit Manager Harry Closter Technician Tex Foote Original Music/Conductor Isadore Goodman Song ‘Dreamtime for Jedda’ Leslie Lewis Raphael Songs Recorded by Bob Gibson Vocals Jimmy Parkinson Special Aboriginal Recording Professor AP Elkin Research Bill Harney Costumes Wendels

MAIN CAST

Jedda Rosalie Kunoth-Monks (as Ngarla Kunoth) Marbuck Robert Tudawali (A.K.A. Bob Wilson) Sarah McMann Betty Suttor Douglas McMann George Simpson-Lyttle ‘Joe’ (Half-Caste) Paul Clarke (as Paul Reynall) Tas Fitzer, Northern Territory Mounted Police Officer Peter Wallis Felix Romeo (Boss Drover) Wason Byers Young Joe Willie Farrar Young Jedda Margaret Dingle Other Nosepeg Tjunkata Tjupurrula (uncredited), as well as Aboriginals from the Pitjantjatjara, Aranda, Pintupi, Yungman, Djauan, Waugite and Tiwi tribes of north and central Australia. Uncredited Indigenous actors in directed roles with the names of Moonlight, Charcoal, Booloo, Millie, May, Nita, Bessie and others unnamed.

Endnotes

| 1 | Assimilation, which had been developing as a policy direction throughout the 1950s, was formalised at the 1961 Native Welfare Conference of Federal and State Ministers: ‘The policy of assimilation means that all Aborigines and part-Aborigines are expected to attain the same manner of living as other Australians and to live as members of a single Australian community, enjoying the same rights and privileges, accepting the same customs and influenced by the same beliefs as other Australians’; see Henry Reynolds, Aborigines and Settlers: The Australian Experience 1788–1939, Cassell Australia, Sydney, 1972, p. 175 |

|---|---|

| 2 | Stuart Cunningham, ‘Charles Chauvel: The Last Decade’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, p. 33. |

| 3 | The producer in question is Merian C Cooper; see Charles Chauvel, ‘Our Outback Is a Rich Field for Film Makers’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1950, p. 2. |

| 4 | Charles Chauvel, ‘Darwin’s Glamour Is Where You Find It’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September 1950, p. 11. |

| 5 | Charles Chauvel, quoted in ‘Stark Color Film to Be “Shot” in N.T.’, The Argus, 19 June 1951, p. 3. |

| 6 | Elsa Chauvel, quoted in Jane Mills, Jedda, Currency Press, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, p. 24. |

| 7 | ibid. |

| 8 | Tom O’Regan, ‘Australian Film in the 1950s’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, pp. 3–6. |

| 9 | ‘Forever Amber – but Never Jedda Role’, The Courier-Mail, 13 September 1952, p. 1. |

| 10 | Cunningham, op. cit., p. 32. |

| 11 | ibid., p. 29. |

| 12 | Elsa Chauvel, My Life with Charles Chauvel, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1973, p. 122. |

| 13 | Karen Fox, ‘Rosalie Kunoth-Monks and the Making of Jedda’, Aboriginal History, vol. 33, 2009, p. 79. |

| 14 | Colin Johnson, ‘Chauvel and the Centring of the Aboriginal Male in Australian Film’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1988, p. 55. |

| 15 | Elsa Chauvel, op. cit., p. 116. |

| 16 | Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, quoted in Maureen Bang, ‘“Jedda” and Her Foster Family’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 June 1971, p. 3. |

| 17 | Fox, op. cit., p. 81. |

| 18 | Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, Message Stick interview, 18 February 2005, as cited in Fox, op. cit., p. 86. |

| 19 | Mills, op. cit., p. 71. |

| 20 | Dave Palmer & Garry Gillard, ‘Aborigines, Ambivalence, and Australian Film’, Metro, no. 134, 2002, p. 112. |

| 21 | Benjamin Miller, ‘The Mirror of Whiteness: Blackface in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, ‘Spectres, Screens, Shadows, Mirrors’ special issue, 2007, pp. 148, 149. |

| 22 | Cunningham, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 23 | ‘Chauvel Film Cost £90,823’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 December 1954, p. 9. |

| 24 | ‘Jedda’s £50,454’, The Argus, 8 December 1956, p. 25. |

| 25 | ‘Superb Scenery in Jedda’, The Sun, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. |

| 26 | ‘The Real Importance of Jedda (It’s Box Office … and It’s Australian)’, ‘Salute to Jedda’, Film Weekly, 14 April 1955, p. 1. |

| 27 | ‘Jedda Boost to Australia’, The Daily Telegraph, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. |

| 28 | ‘Film Jedda Is Gripping’, The Advertiser, 5 January 1955, quoted in Film Weekly, 13 January 1955, p. 13. |

| 29 | ‘Jedda’, The Australian, 15 June 1955, p. 6. |

| 30 | ‘Jedda’, Film Weekly, 12 May 1955, p. 13. |

| 31 | Mills, op. cit., p. 13. |

| 32 | Paul Kalina, ‘Chauvel’s Jedda Led the Way’, The Age, 15 December 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/Film/Chauvels-Jedda-led-the-way/2004/12/14/1102787061956.html>, accessed 9 March 2015. |

| 33 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Jedda’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/jedda/notes/>, accessed 9 March 2015. |

| 34 | Allison Craven, ‘Heritage Enigmatic: The Silence of the Dubbed in Jedda and The Irishman’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 28–30. |

| 35 | Barbara Creed, ‘Jedda’, in Geoff Mayer & Keith Beattie (eds), The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand, Wallflower Press, London, 2007, p. 70. |

| 36 | Mills, op. cit., pp. 67–8. |

| 37 | Karen Jennings, Sites of Difference: Cinematic Representations of Aboriginality and Gender, Australian Film Institute, Research and Information Centre, South Melbourne, 1993, p. 29. |

| 38 | ibid., p. 33. |

| 39 | Creed, op. cit., p. 68. |

| 40 | Mills, op. cit., p. 38. |

| 41 | Creed, op. cit., p. 67. |

| 42 | Catherine Kevin, ‘Solving the “Problem” of the Motherless Indigenous Child in Jedda and Australia: White Maternal Desire in the Australian Epic Before and After Bringing Them Home’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 4, no. 2, 2010, p. 147. |

| 43 | ‘Forever Amber – but Never Jedda Role’, op. cit. |

| 44 | Rose Lucas, ‘Original Sins: Imaging Maternity in Australian Cinema’, Meridian, vol. 18, no. 2, 2002, pp. 243–65. |

| 45 | Mills, op. cit., p. 5. |

| 46 | Cunningham, op. cit., p. 36. |