Neither Heard nor Seen

It is 1958 and I am eight years old. My mother is knitting with quiet deliberation in her armchair next to the open coal fire (this is the North of England where coal used to be the major industry and to consume it conspicuously a moral responsibility). I am sitting at the dining table with the ‘nice’ young policeman who is taking down my statement with a pencil. I am excited and rather flattered by all this adult attention, and getting rather carried away with my account of what the ‘nasty’ old man whom we met while feeding the horses on Temple Park did next. Actually, he didn’t do much. He didn’t expose himself, like the old man by the toilet block at the playground, nor did he show us pornographic images of women with ginormous breasts while we sat on the swings, another memorable occasion. No – he simply picked up first Lizzie and then me so that we could give a sugar lump to our favourite horse, and slipped his rough and scratchy finger up our knicker legs. Although I’d thought it a bit unpleasant at the time and refused to give the horse any more sugar lumps, I’d completely forgotten about it until the policeman knocked on the door. Lizzie had told her parents and it was they who called the police.

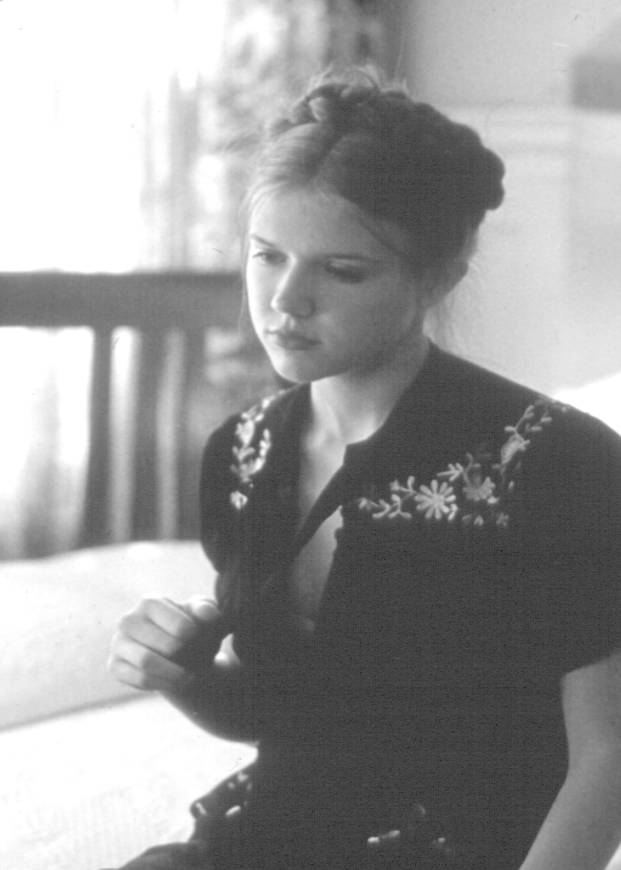

I am sixteen years old. My mother walks into my bedroom and presents me with three paperback books. ‘I think these are yours now’, she says with an embarrassed smile and leaves. The books are John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. If this is my mother’s idea of sex education at the age of consent, it’s an odd one. What I don’t tell her is I’ve read them all before (at least the best bits), nor that I have already been sexually active. I have, however, made the decision to give sex up, at least until I get to University, having realised that an academic route is possibly the easiest out of the increasingly depressed North East (they’ve closed the coal mines and the shipyards are struggling) and into an imagined literary world with which I am more deeply in love than Raymond Whitehead who runs the Walzers at the Amusement Park.

My son aged ten comes into the bedroom where I am reading. ‘Is it true’, he asks, ‘that Monica Lewinsky gave President Clinton a blow job?’ ‘Apparently’, I answer – and he returns to the living room to watch the rest of the News.

It’s the 25th of February, 1999 and I’m contemplating the front page of The Age newspaper. The main headline of the day is “PM Puts Drugs on the Agenda” and concerns the Prime Minister’s conservative response to the increasing problem of heroin addiction and drug related deaths. Below it is an article in which a Judge hits out at a proposed private youth jail and is quoted as saying:

I am very troubled that we may finish up in a situation where the state effectively abrogates its responsibilities to young people as it did in the past.

Another item, with pictures, concerns the stabbing of a woman outside the Family Court in Newcastle, Australia, by her estranged husband. Her four year old son who witnessed the incident is shown being led away by police officers. Another item is about the failure of the Cricket Board to punish cricketers Shane Warne and Mark Waugh for receiving payments from an illegal bookmaker in Sri Lanka some four years earlier. Teasers for the articles inside include “Nation Searches For Answer to Gun Violence” and along the top, level with the masthead: “Why the New Lolita Should Be Banned”. It is this article which initially attracts my attention and to which I first turn, only later to reflect on the juxtaposition of images on the front page and what they say about the society in which I apparently live.

The article by Susan Edwards, who is a visiting fellow at the Australian National University’s Law Faculty, begins thus:

I am a left-wing libertarian, a defender of free speech, a campaigner for abolitionism. I am also a feminist, a campaigner and an activist involved in issues of women’s struggles in Britain since the 1970s involving domestic violence, rape, and child protection. It follows, therefore, that I am viscerally repelled by any censorship of ideas, as I am viscerally opposed to the promulgation of child pornography and the sexualisation of children in any medium.

Let’s just hold on to the ‘visceral’ for a moment. The viscera are usually defined as the internal organs of the body, specially the abdomen. I think what Edwards is trying to say is that she has a gut reaction to the censorship of ideas as well as a gut reaction to child pornography and the sexualisation of children in any medium. I’m completely intrigued by this word visceral in both its contexts. Like Edwards, I am an academic; like Edwards I would call myself a feminist and a libertarian; like Edwards I’m deeply troubled by child pornography and the exploitation of children. How come, one might ask, do I so completely disagree with her on the relationship between these social problems and the film, Lolita? Why am I not caught out by the same contradiction? There is, by the way, no evidence in the article that Edwards has actually seen the film: it’s the idea of it which so viscerally repels her.

11th of March, 1999 and the Lolita controversy is running like a feral magic pudding. An article in The Australian newspaper suggests that the Prime Minister will move to ban the film to appease Independent Senator Harradine whose crucial vote is needed in other matters of State. Everybody denies this. Meanwhile Liberal Backbencher Larry Schutz, who also has not seen the film, suggests that the academics consulted by the Office of Film and Literature Classification who are preparing to grant the film release with an R18 rating were ‘out of touch’ with the broader community views on pedophilia.[1]This is not the first time during the nineties that attempts have been made to marginalise and exclude academics (and film reviewers) in public debate about censorship in Australia. Rebecca Huntley discusses a number of similar instances, including the debate over the Pasolini film Salo and the operations of the Senate Committee on Community Standards in her paper “Queer Cuts: Censorship and Community Standards”, Media International Australia, no.78, November, 1995, pp.5–12.

Academics like me, I think, but not like Susan Edwards. And I start to wonder what is really going on, what is actually at stake here. How are academics being figured in this unfolding controversy and what about childhood innocence? Let me start with childhood innocence.

I’ve used some of my own childhood experiences here, not because I think they are a-typical, but because I think they are probably very typical. I ‘think’ I had a reasonably abnormal-normal childhood. By the time I was eight, I knew about dirty old men, D.O.M.s my big sister called them, and how one should avoid them. The year was 1958, three years after the publication of Nabokov’s novel which was conceived, so he suggests in an afterword, in 1939. By the time I was sixteen, I had quite a history of sexual experimentation, again quite usual but done at my own pace, in terms of my own choosing, inflamed no doubt by a burgeoning youth culture which was moving in the direction of ‘free love’ and full blown hippiedom. What I did not have was any understanding of systematic long term child abuse or child sexual assault. Child abuse was simply not talked about, even though I know now that it was happening in an adjacent community in Newcastle, England, to little Mary Bell born in 1957 who at age eleven murdered two small boys in ways which mimicked the scenarios of her own childhood traumas.[2]Gitta Sereny, Cries Unheard: The Story of Mary Bell, Macmillan, London, 1998.

My first question is therefore this: how has the concept of childhood innocence come to hold such rhetorical and emotional force in debates about the media in the face of the overwhelming evidence from our own personal experience, and the experiences of others which are reported as matters of fact, that it is already long gone?

From the moment they are born, children are socialised into a world where innocence may be revered but is routinely exploited, leading to the worrying proposition that loss of innocence may be the best form of protection. Knowing that what is being done to you is not acceptable or right means knowing that it is wrong and being able to say so to someone who will do something about it. A writer friend told me that she had been appalled by a poster in a rural school which she saw recently which simply read ‘Daddy, please don’t hurt me’. Primary schools, including the one attended by my son, know only too well that children have to learn to say ‘no’ and have to learn how to ‘tell’, and many run programs for teachers and children to enable this. However, telling a parent or teacher about the sexual approaches of a D.O.M. may be much easier than telling them what Daddy did. The real scandal is that even when schools or social services may identify a child at risk, the state regularly fails to provide adequate support because of cuts to the social welfare programs with the power to intervene. This leads one to the testy conclusion that if the government were serious about child abuse, then it would quit focusing on films and invest more money in those services which might then be empowered to make a real difference to the lives of real children.

Question number two: how can we insist on the protection of childhood innocence in the face of recent and past history which reveals just how often those empowered to protect that innocence (parents, legal guardians, the church, the state) have abused that trust?

Hence I find myself deeply sceptical about calls for censorship in the media as if the media were the problem. Even though, like Susan Edwards, I may ‘viscerally abhor’ the idea of child pornography, I suspect that banning it in whatever form it appears – and Lolita is being cast as one of those forms – will not make the problem of pedophilia or child abuse go away. The Lolita case strikes me as a tip of the iceberg issue, and like all icebergs, it’s what is going on beneath the waterline – out of sight – which is the real problem.

Lolita may indeed be providing politicians, journalists and academics with a chance to clash rhetorics over the issue of childhood innocence and censorship in public; these debates may indeed be about a struggle for definitions and limits in censorship, and yet, I would argue, this debate about Lolita – and other similar debates encompassing that other usual suspect, children and screen violence – are symptomatic of a much larger anxiety. This anxiety has to do with how the symbol of the ‘child’ in all its emotional force has come to stand for that which defines us as adults. One aspect of the current debate therefore concerns what kind of a society we have created for ourselves and how this should be represented in public. The real child, watching the evening news and wondering about Bill Clinton’s sex life, doesn’t get much of a look in.

Vladimir Nabokov understood childhood sexuality. The real Dolores Haze, if I might call her that, was no sexual innocent of twelve and a half. Lolita lost her virginity at Camp Q, crassly renamed Camp Climax in Kubrick’s crude first film version of the book, in the capable hands of her sophisticated peer, Elizabeth Talbot, and the ‘coarse and surly but indefatigable’ Charlie Holmes, age thirteen, the son of the camp mistress.[3]Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita, Corgi, London, 1961, p.144. Humbert Humbert’s crime, of which he is always acutely aware, is to feign innocence when Lolita offers to teach him what she knows, and to let her. From this moment Lolita, a child below the statutory age of consent, is coerced into a full and ongoing sexual relationship with an adult who imposes his desire upon her even when he knows both that she is unhappy and that this is wrong.

From the few clips which I have seen of Adrian Lyne’s film, including the scene where Humbert picks up Lolita from Camp Q and she tells him she has been ‘unfaithful’ to him, and compels him to kiss her, Lyne has remained remarkably faithful to the original book, which Graham Greene described at the time as ‘brilliant’ and of which Kenneth Allsop in The Daily Mail said:

Brilliantly written … a disquietingly sombre exposure of a pervert’s mind, and finally dreadfully moral in its almost melodramatic summing up of the wages of this particular sin.[4]ibid. p.341.

But, as I’ve already noted, this current debate is not just about the book, or the film, or Dolores Haze. It’s also about who gets to speak and who gets to be spoken, and in a bizarre but not unprecedented turn, I find myself as an academic with two degrees in English Literature and a Ph.D in media education (which involved a year long study of sixteen year old girls and the role of the media in their lives) marginalised because I am not ‘in touch’ with broader community views on pedophilia. This leads me to another question: what does ‘in touch’ mean and what or where is this broader community with which politicians are more in touch than academics?

The autobiographical turn in this paper has therefore been quite deliberate. Before becoming an academic I was, and still am, a member of a number of different communities: communities, I might add, from the beleaguered North East of England to the relatively affluent Eastern suburbs of Melbourne, in which I have experienced and observed as a child, a student, a teacher and now as a parent, how children live and are indeed affected by the political decisions which have implications for the quality of their lives. And I have watched the State progressively abrogate responsibility in that regard. I currently serve on the council of my son’s state run primary school and know in precise and measurable detail just how much the state cares about children’s education in financial terms, and how hard it is trying to divest itself of responsibility for the school and is seeking to transfer that responsibility, and the economic burden which this entails, back onto the community in which I live.

And I’m also a member of an academic community, or what’s left of it, after successive governments have demonstrated the high regard for the work we do by imposing upon us a managerial culture of economic rationalism which has radically altered the way in which we and our students think about university education. I’ve watched valued colleagues coerced to take ‘packages’ (to be replaced by casual staff at exploitative rates), and wondered who would be next. I’ve observed how students struggle to pay their fees, and find a course which might make those fees worthwhile as they try to juggle study and the full time work which they undertake in order to financially survive. But my views, of course, are not representative of the ‘broader community’ with which I am, apparently, not in touch.

What makes this even more ironic is that this assertion is being made in relation to the analysis of a film and its imagined social impact. Therefore, precisely because I am qualified in the study of literature, the media and the history of research relating to audiences from the nineteenth century to the present; and precisely because as an engaged academic I am constantly testing the theories against my own lived experience as I have tried to demonstrate here, my views don’t count – although those of academics who have qualifications in other areas and who tow the conservative line (like Susan Howard) do. It’s an odd state of affairs. The State, in the good old days when it did pay for education, has trained me as an academic, specialising in media and audience research, only to tell me that I am not qualified to speak on an issue which falls quite precisely within my area of expertise – and this is so because I am, supposedly, ‘out of touch’ with the community. Which community? What community? Whose community?

It’s a double insult really, and it would be only too easy to trade in this kind of sniping. In the end, it’s the same old story. A media text has become the centre of a debate in which various interest groups are using it as a platform to broadcast their legitimate outrage about a social problem, the solution to which lies outside the domain of media representation and in the field of social and political action. I suspect that the desire to censor and restrict such texts therefore stems from a combination of different factors, some, or all of which, are in play at any one time. Firstly, a genuine desire to do something, or at least to be seen to be doing something, about a social problem of genuine concern. Secondly, a suspicion that the media texts which we consume in some ways define us as a society and an understandable, though doomed, desire to eliminate that which we don’t like about our society by eliminating the text. Anyone who suggests that censoring the text may not be the solution then stands accused of not caring about the social problem it is perceived to represent and exacerbate. It’s a hard one, made harder by the assumption of us and them positions, and the invocation of a notion of community which includes some but excludes others. The lines have been drawn.

So what are we really arguing about in this instance? Adrian Lyne’s film? Or who has responsibility for children’s welfare in our society? That’s the big one, and that’s the one which is really being dodged by the State as it assumes the much easier option of drawing a veil over our eyes. Let us therefore note in passing the following duplicitous moves: as the State abrogates its responsibility for social welfare and public services, it simultaneously assumes an increasingly paternalistic role with regard to the images which reflect upon the society thus produced; images which in the end will impinge but slightly on the lives of those put at risk by such abrogation. It’s not looking too good for a film culture in Australia which might move beyond the quirky to the critical.

This paper was originally presented to The Limits of Tolerance conference, Centre for Research into Textual and Critical Studies, University of Wollongong, on the 26th of March, 1999.

Endnotes

| 1 | This is not the first time during the nineties that attempts have been made to marginalise and exclude academics (and film reviewers) in public debate about censorship in Australia. Rebecca Huntley discusses a number of similar instances, including the debate over the Pasolini film Salo and the operations of the Senate Committee on Community Standards in her paper “Queer Cuts: Censorship and Community Standards”, Media International Australia, no.78, November, 1995, pp.5–12. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Gitta Sereny, Cries Unheard: The Story of Mary Bell, Macmillan, London, 1998. |

| 3 | Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita, Corgi, London, 1961, p.144. |

| 4 | ibid. p.341. |