Paul Moulds is the kind of man who’ll sooner meet a challenging situation with a smile than a frown. That’s just as well: as a major in the Salvation Army who has spent his life supporting some of Australia’s most vulnerable groups, including homeless teens and asylum seekers, he is never short of a challenge. Whether it’s dragging a clothes hamper full of food up several flights of stairs or encountering nineteen athletes who have fled from the Commonwealth Games to seek asylum on his doorstep, he seems to draw on a relentless positivity that means laughter is never far away – even if it’s sometimes tinged with exasperation at yet another seemingly impossible situation he has to resolve.

For Paul, helping those in need is more than a career; it is a mission and vocation he has dedicated his life to.[1]Paul Moulds, in Sarah Kanowski, ‘Bringing Kids Back from the Edge’, Conversations, ABC Radio, 20 July 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/conversations/conversations-paul-mould/9992962>, accessed 14 February 2020. In his office hangs a beautifully calligraphed quote attributed to cricketer and missionary CT Studd – a gift presented to him when he left school, aged eighteen, by a friend who believed it foretold Paul’s future:

Some want to [live] within the sound of church or chapel bell; I want to run a rescue shop within a yard of hell.[2]Cited in ibid.

Just how close to hell Paul’s work can be was first brought to the public consciousness in 2008, when feature documentary The Oasis (Ian Darling & Sascha Ettinger Epstein) shared a glimpse of the lives of homeless teenagers using the services of the titular shelter for youth in Sydney. The violence, crime, drug abuse and severe mental-health struggles depicted in the film caused a national response rarely enjoyed by social-issues documentaries, leading then–prime minister Kevin Rudd to commit to halving youth homelessness by 2020.[3]See Fiona Hall, Life After the Oasis study guide, ATOM, Melbourne, 2019, p. 2. In reality, the tumultuous period following this promise brought us six prime ministers in less than a decade, and, today, homelessness and inequality in Australia are only getting worse.[4]See Melissa Davey & Christopher Knaus, ‘Homelessness in Australia Up 14% in Five Years, ABS Says’, The Guardian, 14 March 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/mar/14/homelessness-in-australia-up-14-in-five-years-abs-says>; and Productivity Commission, Rising Inequality? A Stocktake of the Evidence, August 2018, available at <https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/rising-inequality/rising-inequality.pdf>, both accessed 14 February 2020. In a bid to bring these forgotten kids back onto the agenda, Ettinger Epstein tracked down many of the film’s participants, documenting how their lives turned out in her film Life After the Oasis (2019).

The images that shocked so many in The Oasis were the stuff of everyday life for Paul and his equally dedicated wife, Robbin, in 2008, with the couple heading up the chaotic shelter and its associated youth-support programs. Their love and commitment for the troubled teens at the Oasis were – and are – tangible, so it’s perhaps surprising that, ten years on, Ettinger Epstein found the couple had moved on from their inner-city post.

As majors in the Salvation Army, Paul and Robbin relinquished their right to choose where they live or work, so that they may be posted where their skills and experience are deemed most needed. In a 2018 interview, Paul shared that, not long after the release of The Oasis, the Salvation Army reappointed him to a more advocacy-driven leadership role in the organisation’s head office, of which he simply says, ‘It wasn’t me, that’s certainly true.’[5]Moulds, op. cit. Perhaps in an effort to find his way back to the gates of hell, Paul then became the Salvation Army’s director of offshore missions in Nauru and Manus Island in 2012, working to ensure that offshore detainees receive some form of humanitarian aid and comfort. Seeing the immense struggle experienced by the people he sent overseas, Paul, accompanied by Robbin, soon chose to move to Manus – a time that, Paul now says, evoked the first genuine personal crisis of his life, and which caused him and Robbin to take an eight-month career break upon their return to Australia.[6]ibid.

By the time Ettinger Epstein caught up with the Mouldses in 2018, their path had taken them to Auburn, one of Australia’s most ethnically diverse and also impoverished suburbs. While leading a community centre primarily serving recently settled migrants and poverty-stricken Australians may seem a far cry from their chaotic days at the Oasis, Paul and Robbin were required to tap into many of the same skills – their work is often as much about instilling a sense of hope and community in the people they meet as it is about practical concerns like organising food, visa applications or housing.

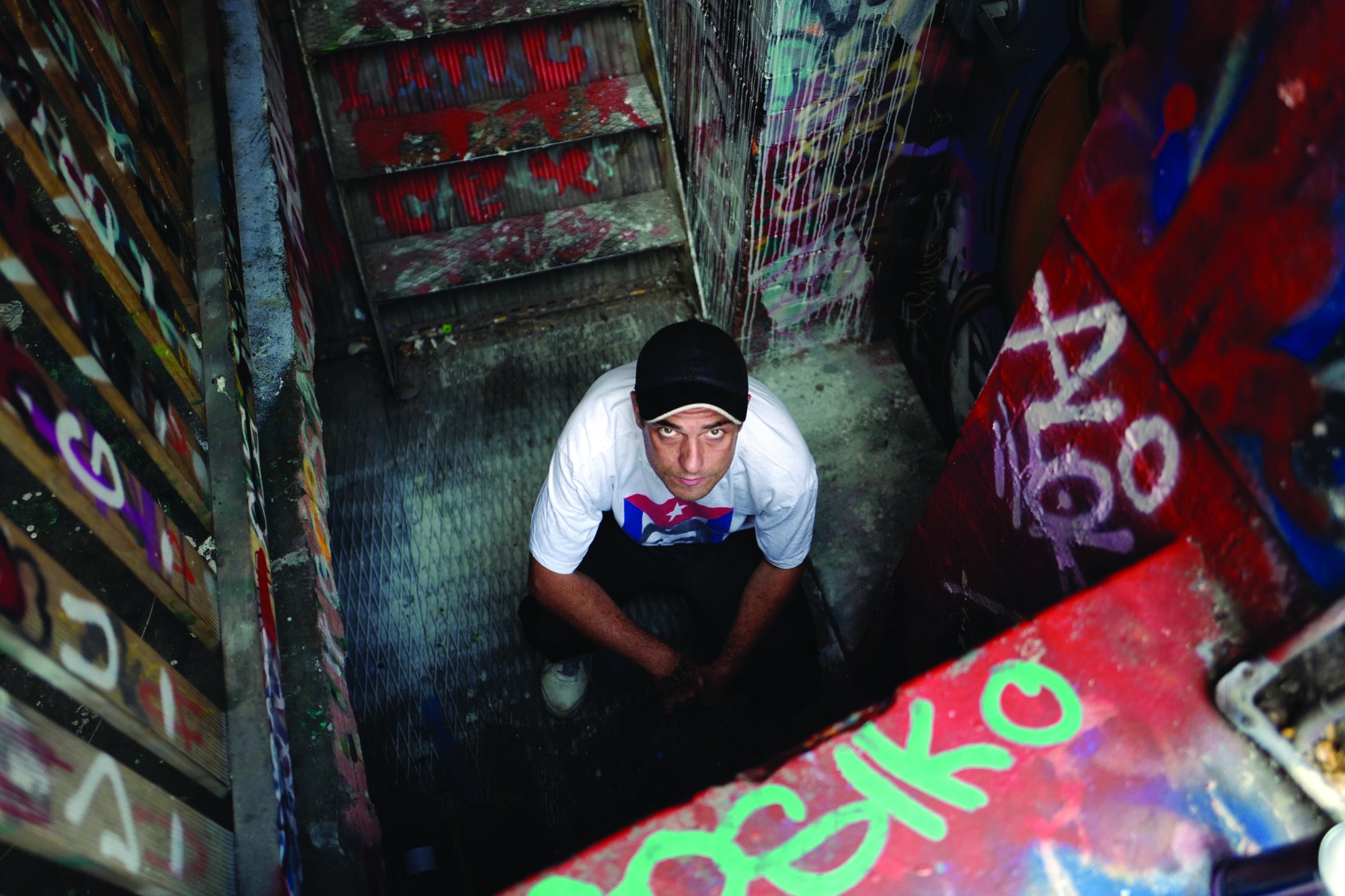

And hope, as it turns out, is regularly justified. A decade after the trials of their teenage years, many of the now-adults Ettinger Epstein meets in Life After the Oasis have gone on to build relatively settled lives for themselves. Darren and Owen, two of the most troubled boys of the original film, have left drugs and rage behind and are now themselves working with the Salvation Army. Owen also started to release hip-hop tracks under the name Ozone, and founded Street2Stage, an initiative to help other homeless teens find refuge in music.[7]Lauren Martin, ‘Salvos Homelessness Work to Feature on SBS’, Others, 8 November 2019, <https://others.org.au/news/2019/11/08/salvos-homelessness-work-to-feature-on-sbs/>, accessed 14 February 2020. Emma broke up with her abusive and drug-dependent boyfriend, and now finds purpose and healing in raising her two young children with the love she never experienced. Chris has reconnected with his family, and is managing his addiction to methadone.

In the absence of sufficient funding and a support infrastructure set up to allow genuine, long-term assistance for more than just the most urgent cases, being encouraging is sometimes the only thing frontline workers like Paul and Robbin can do.

But their paths to relative stability were far from straightforward, and challenges remain for all of them – challenges that clearly expose crucial funding and policy gaps that hinder true long-term rehabilitation for any Australians experiencing serious adversity, including homeless teenagers. Shortly after The Oasis showed Darren receiving a council flat, lack of accessible mental-health support saw him burn his new home to the ground during a schizophrenic attack. He subsequently spent two years in jail for arson. Now, as we see in Life After the Oasis, he is back in a small council flat and focused on managing his psychological and physical health, not to mention staying off drugs. But his new lifestyle means he has lost much of his social network, and he feels lonely and directionless. Owen’s work with the Salvos may give him a sense of belonging and his music may offer a source of healing and empowerment, yet he is still threatened by homelessness (during the Life After the Oasis shoot, he was staying in the garage of an Auburn house managed by Paul). While Emma and her two younger kids are thriving as a family, she has lost custody of her two older children. And, while Chris has turned his back on heroin, the methadone that replaced it is playing havoc with his body.

Despite ongoing challenges, these are clear success stories – Darren, Owen, Emma and Chris are off the streets, off illegal drugs and looking to the future with hope. Sadly, the same can’t be said for all the teens from the original film. Haley, who was kicked out of home aged thirteen by her drug-dependent mother and her abusive partner, was one of the most memorable and charismatic kids featured in The Oasis. Her brushes with extreme violence, occasional rageful outbursts and severe heroin addiction – which cost her a staggering A$600 per day by the end of the documentary – stood in contrast with the innocent and childlike poems and diary entries she’d share, and with her dream to one day be married and become a nurse.

Haley always shared a particularly close connection with Robbin, whose quest to track her down once more forms one of the central narrative strands of Life After the Oasis. It’s a frustrating endeavour that feels almost like a detective drama, as Robbin calls phone number after phone number only to hear that Haley owes money to the stranger at the end of the line, hasn’t been seen in weeks or had left just two days earlier. Despite Robbin eventually managing to reach Haley, and even flying to Melbourne to attempt a meet-up, in the end, it is Paul who gets to hug the woman, who is now in her thirties, in a homeless shelter in Melbourne.

Ten years on, Haley still has a spark in her eye, and still dreams of the future – hoping to become an interior designer, and maybe reconnect with the daughter she gave up as a teenager. But her body betrays years of struggle, and her smile is now almost toothless as she tells Paul about her journey over the past decade, which was largely defined by homelessness, drugs and even jail. Now on the streets of Melbourne, it seems unlikely the young woman will ever get to realise her dreams, but Paul is as positive and loving as ever, encouraging her to keep fighting for her future.

In the end, in the absence of sufficient funding and a support infrastructure set up to allow genuine, long-term assistance for more than just the most urgent cases, being encouraging is sometimes the only thing frontline workers like Paul and Robbin can do. Too often, teens and adults in desperate need of social services, mental-health support and affordable housing instead find themselves incarcerated, adding yet another layer of difficulty to the search for stability. According to the Health of Australia’s Prisoners report by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘About one-third (33%) of prison entrants said they were homeless in the 4 weeks before prison,’ and, ‘More than half (54%) of prison discharges expected to be homeless on release’.[8]Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The Health of Australia’s Prisoners, 2018, p. viii. Prison entrants were sixty-six times more likely to be homeless than the general population, and prisoners aged eighteen to twenty-four were both most likely to have been sleeping rough or in temporary accommodation before prison and most likely to return to various forms of homelessness upon release.[9]ibid., pp. 23–5.

In 2018, the Rudd government’s ten-year National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness and its National Affordable Housing Agreement both expired, having fallen desperately short of their target to halve homelessness by 2020, and were replaced by the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA). Despite committing to maintain the A$1.3 billion Commonwealth investment to tackle the problem, the NHHA has effectively brought funding for homeless services across Australia to the lowest it has been in a decade, ignoring the impact of inflation and discontinuing vital secondary funding agreements like the National Rental Affordability Scheme.[10]See Vivienne Milligan, ‘The New National Housing Agreement Won’t Achieve Its Goals Without Enough Funding’, The Conversation, 17 July 2018, <https://theconversation.com/the-new-national-housing-agreement-wont-achieve-its-goals-without-enough-funding-99936>, accessed 14 February 2020. There are also serious questions about the NHHA’s ability to reach the communities that need it most, with spokespersons from several homeless-support services across the nation highlighting the disparity in funding based on states’ population sizes, which leaves the sparsely populated but highly impacted Northern Territory at a serious disadvantage.[11]See Sowaibah Hanifie, ‘Homeless People Failed by the Commonwealth Funding Model, Experts Nationally Say’, ABC News, 14 July 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-13/advocates-say-homeless-people-failed-by-funding-model/11303512>, accessed 14 February 2020. The NHHA is set for review in 2022 to determine funding arrangements for 2023, suggesting the current crisis will only intensify over the next twenty-four months.[12]ibid.

Ettinger Epstein embarked on this follow-up project to try to bring these forgotten kids back onto the national agenda and reverse the current trend of worsening conditions. Whether she will ultimately be successful remains to be seen, but Life After the Oasis is unlikely to have the same impact its predecessor did. For one, the news cycle over the last decade has significantly shortened, and is currently populated by crisis after crisis; it is questionable whether the film, and any associated advocacy work, will be able to steal many headlines compared to Donald Trump’s America, Brexit, devastating natural disasters like the Australian bushfires and the (at the time of writing, ongoing) coronavirus pandemic. The film itself, while well crafted, also lacks some of the impact of the original. This is in part because its focus is necessarily somewhat diluted, due to its subjects’ diverging journeys over the past decade and the fact that Paul and Robbin are now based in Auburn; asylum-seeker rights and poverty are explored alongside homelessness, addiction and mental health. The kids who cut such disturbing figures of desperation and violence in 2008 have matured into far calmer and introspective adults in 2018, which makes for more nuanced but also less dramatic viewing – not by any means a cinematic weakness, but this does make the film less potent at stirring large swathes of Australians into action.

Despite the lower likelihood for widespread impact, Life After the Oasis offers a valuable added dimension to its more visceral predecessor. Whereas The Oasis brought a national crisis to the public consciousness, Life After the Oasis provides evidence that interventions like those led by Paul and Robbin can truly turn lives around, and that even teens who seem violent and desperate have the potential for rehabilitation with the right form of support. It also shines a light on the difficulties many people impacted by homelessness and addiction face once they leave crisis support. Ettinger Epstein is already working on a follow-up project that will broaden this latter perspective further: The Department (set for release in 2021), which will explore the complexities of child protection and the intergenerational trauma caused by poverty and homelessness.[13]See ‘The Department’, Shark Island Institute website, <https://sharkisland.com.au/portfolio/the-department/>, accessed 14 February 2020.

Even if it doesn’t generate the same public outcry as its predecessor, Life After the Oasis remains a valuable tool for those seeking to better the lives of some of Australia’s most vulnerable people – after all, not all impact has to be governmental or societal in scale to be meaningful. In the film itself, one of the social workers Robbin speaks to during her search for Haley excitedly shares that she chose her career path after seeing The Oasis in high school. Now, a new generation of high school kids will have the chance to learn about the struggles some of their peers grapple with on the street and beyond,[14]The film is freely available to all schools across Australia. Teaching resources aligned with the national curriculum across several subjects also exist – see Hall, op. cit.; and ‘Life After the Oasis’, Cool Australia website, <https://www.coolaustralia.org/lifeaftertheoasis/>, accessed 14 February 2020. and, if not directly inspired to take up social work, can develop a more compassionate understanding of the issues that lead to homelessness and addiction.

On a more personal level, the very act of Ettinger Epstein revisiting her subjects arguably helps them to feel seen and heard, and to foster pride in their journey thus far as well as purpose for the future. After all, a sense of community and belonging is just as essential as a roof over one’s head in the fight for lasting change. Ettinger Epstein’s decade-long commitment to these once-lost souls is as much a piece of that puzzle as Paul’s ability to meet them with a smile, no matter how dire the situation may be.

Endnotes

| 1 | Paul Moulds, in Sarah Kanowski, ‘Bringing Kids Back from the Edge’, Conversations, ABC Radio, 20 July 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/conversations/conversations-paul-mould/9992962>, accessed 14 February 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Cited in ibid. |

| 3 | See Fiona Hall, Life After the Oasis study guide, ATOM, Melbourne, 2019, p. 2. |

| 4 | See Melissa Davey & Christopher Knaus, ‘Homelessness in Australia Up 14% in Five Years, ABS Says’, The Guardian, 14 March 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/mar/14/homelessness-in-australia-up-14-in-five-years-abs-says>; and Productivity Commission, Rising Inequality? A Stocktake of the Evidence, August 2018, available at <https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/rising-inequality/rising-inequality.pdf>, both accessed 14 February 2020. |

| 5 | Moulds, op. cit. |

| 6 | ibid. |

| 7 | Lauren Martin, ‘Salvos Homelessness Work to Feature on SBS’, Others, 8 November 2019, <https://others.org.au/news/2019/11/08/salvos-homelessness-work-to-feature-on-sbs/>, accessed 14 February 2020. |

| 8 | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The Health of Australia’s Prisoners, 2018, p. viii. |

| 9 | ibid., pp. 23–5. |

| 10 | See Vivienne Milligan, ‘The New National Housing Agreement Won’t Achieve Its Goals Without Enough Funding’, The Conversation, 17 July 2018, <https://theconversation.com/the-new-national-housing-agreement-wont-achieve-its-goals-without-enough-funding-99936>, accessed 14 February 2020. |

| 11 | See Sowaibah Hanifie, ‘Homeless People Failed by the Commonwealth Funding Model, Experts Nationally Say’, ABC News, 14 July 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-13/advocates-say-homeless-people-failed-by-funding-model/11303512>, accessed 14 February 2020. |

| 12 | ibid. |

| 13 | See ‘The Department’, Shark Island Institute website, <https://sharkisland.com.au/portfolio/the-department/>, accessed 14 February 2020. |

| 14 | The film is freely available to all schools across Australia. Teaching resources aligned with the national curriculum across several subjects also exist – see Hall, op. cit.; and ‘Life After the Oasis’, Cool Australia website, <https://www.coolaustralia.org/lifeaftertheoasis/>, accessed 14 February 2020. |