Online media platforms offer unique opportunities for filmmakers and storytellers to engage a variety of audiences. Whether simply uploading short films to a website like YouTube or Vimeo or tailoring content to a specific platform and its features, creators have the capacity to reach audiences in a variety of ways.

One of the most prominent services of this kind to have emerged in recent years is short-video platform TikTok, which launched internationally in 2017 and last year became the most frequently used social media website in Australia (in terms of time users spent on the app);[1]See ‘Digital 2022 Australia: Online Like Never Before’, We Are Social website, 9 February 2022, <https://wearesocial.com/au/blog/2022/02/digital-2022-australia-online-like-never-before/>, accessed 18 June 2022. it now has over 1 billion users globally.[2]See Kim Lyons, ‘TikTok Says It Has Passed 1 Billion Users’, The Verge, 27 September 2021, <https://www.theverge.com/2021/9/27/22696281/tiktok-1-billion-users>, accessed 2 September 2022. Given TikTok’s reach and unique visual language, filmmakers can benefit greatly from learning how to use the platform to engage and sustain a viewership.

The evolution of the web series

One of the earliest web series to emerge on a social media platform, Lonelygirl15, made its first appearance in June 2006.Through the then-nascent ‘vlogging’ (or video blogging) format, the YouTube series introduced the audience to an ostensibly real sixteen-year-old girl, Bree (Jessica Lee Rose), as she shared interesting facts about her family, with hints dropped along the way that they might have strange links to a cult. Viewers soon began questioning the authenticity of Bree’s story, and online forum users sought to debunk her claims. Eventually, three months after the series’ launch, creators Miles Beckett, Mesh Flinders, Greg Goodfried and Amanda Goodfried publicly admitted that the production was fictional; they continued releasing episodes of the series until it ended in 2008.[3]See Elena Cresci, ‘Lonelygirl15: How One Mysterious Vlogger Changed the Internet’, The Guardian, 16 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/16/lonelygirl15-bree-video-blog-youtube>, accessed 2 September 2022.

In the years following Lonelygirl15’s broadcast, the vlogging genre has continued to inspire YouTube narrative productions, such as Pride and Prejudice adaptation The Lizzie Bennet Diaries (2012–2013).[4]See The Lizzie Bennet Diaries YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/user/LizzieBennet/videos>, accessed 7 September 2022. Other unique story ideas that have emerged from the world of YouTube include Marble Hornets (2009–2014), which involved audiences in its development by encouraging them to suggest ideas for the show in the comments;[5]See Marble Hornets YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/user/MarbleHornets/videos>, accessed 7 September 2022. and Who Killed Markiplier? (2017), a four-episode series shot from a first-person vantage point, in which the viewer ‘plays’ an attorney investigating a murder.[6]See ‘Who Killed Markiplier? – Chapter 1’, YouTube, 11 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YoSrocwNYjA>, accessed 7 September 2022. This level of participatory culture has continued to evolve and shape itself around available technologies; as media scholar Henry Jenkins states, such stories are being moulded by younger users in particular ‘wanting the media they want where they want it, how they want it, in the form they want it, when they want it’.[7]Henry Jenkins, in ‘Henry Jenkins – What Is Media Convergence?’, YouTube, 17 May 2012, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFbJCdCoNIc>, accessed 2 September 2022.

New-media narrative stories on other online video platforms include feature film Sickhouse (Hannah Macpherson, 2016), which was distributed exclusively on Snapchat. Following YouTuber Andrea Russett (playing herself) and her group of friends as they spend the night at a haunted house, the film was released on the platform in one-to-ten-second video snippets, building suspense through real-time delays between videos that sometimes lasted hours.[8]See Ben Child, ‘Sickhouse: How the First Ever Snapchat Movie Redefined Viral’, The Guardian, 23 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/22/sickhouse-how-the-social-media-horror-film-went-viral>, accessed 7 September 2022. On Instagram, meanwhile, Eva.Stories used the platform’s highlight feature to show near-daily video stories of a Jewish girl, Eva (Mia Quiney), living in Nazi-occupied Hungary in the 1940s. Audiences watch this narrative slowly unfold: first, her father’s business is taken away from him, then she herself is deported to a concentration camp. Some controversy has surrounded Eva.Stories regarding its anachronistic (and, in some critics’ view, trivialising) use of self-reflexive mobile filmmaking to depict an era without social media.[9]See Isabel Kershner, ‘A Holocaust Story for the Social Media Generation’, The New York Times,30 April 2019, <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/30/world/middleeast/eva-heyman-instagram-holocaust.html>, accessed 19 June 2022. Nonetheless, by presenting the history of the Holocaust via a short-form storytelling medium easily accessible to younger social media users, the series offers useful talking points for its primarily Generation Z target audience to consider.

- Media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously coined the phrase ‘the medium is the message’, suggesting that the method through which information is conveyed is inextricable from how the content itself is understood.[10]See Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964, pp. 7–23. How does using the features of a social media platform to tell a story affect an audience’s understanding of or response to a narrative?

Understanding audience engagement

User-generated content enables audiences to engage and participate alongside the narrative. This is the case with TikTok, where passive audiences contribute to the success and reach of videos. In 2021, journalist Ben Smith analysed an internal company document entitled ‘TikTok Algo 101’, uncovering how videos are scored on the platform and filtered into users’ individual feeds.[11]Ben Smith, ‘How TikTok Reads Your Mind’, The New York Times,5 December 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html>, accessed 17 June 2022. Factors include ‘likes’, comments and ‘playtime’ (including rewatches), each of which increases the chance of a video appearing on users’ ‘For You’ feed. Merely watching a video is thus a simple way for a user to increase its reach on TikTok, while ‘likes’ and comments are even more powerful – and, thus, essential for creators on the platform to solicit.

Audience activity occurs in a number of different ways on TikTok, and the type of interaction that should be prioritised depends on the kind of story a content creator is telling. Comments can be either passive or active; some may not necessarily add meaning to the story, whereas others can form a basis for future videos. As with most other social media platforms, TikTok creators can engage with comments by ‘liking’ or responding to them directly, but a key facet of TikTok is the ability to embed a viewer’s comment in a video response. Filmmakers can use this technique as a form of interactive storytelling, allowing the audience to inform further episodes.

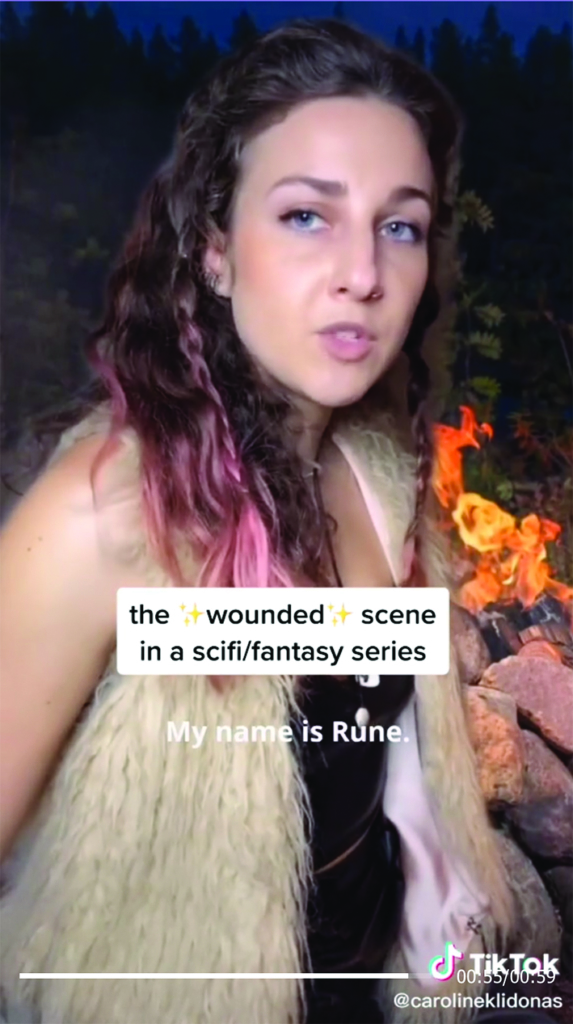

TikTok offers a low barrier for participation to creators and viewers alike. The filmmaking skills needed for production on the platform is minimal, as the app is likely to have an effect inbuilt to achieve the intended outcome. TikTok creator Caroline Klidonas, for instance, parodies the conventions of young-adult dystopian novels in her series Rune; despite not owning a green screen, she is able to use the app’s inbuilt green-screen effect to transport herself into a fantasy world.[12]See Caroline Klidonas TikTok account, <https://www.tiktok.com/@carolineklidonas>, accessed 2 September 2022. Although the feathering around her character is obvious and gaps in the green screen are occasionally visible due to either lighting issues or too much original background detail, these do not significantly detract from the videos’ quality.

TikTok users, whether they be creator or viewer, understand the platform as a ‘sandbox’-style environment for filmmakers, enabling users to play make-believe and embody characters,[13]See Ethan Kurzrock, ‘Intensified Play: Cinematic Study of TikTok Mobile App’, self-published, April 2019, pp. 4–5, available at <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335570557_Intensified_Play_Cinematic_study_of_TikTok_mobile_app>, accessed 12 June 2021. and its prevailing amateur aesthetic has risen in popularity thanks to the online creative conventions that have emerged over the course of the twenty-first century. Film scholar Stephen Groening describes the amateur visual media creator as ‘an experimenter, someone aware of, but not bound by, professional conventions and protocols’.[14]Stephen Groening, ‘Introduction: The Aesthetics of Online Video’, Film Criticism, vol. 40, no. 2, June 2016, available at <https://quod.lib.umich.edu/f/fc/13761232.0040.201/–introduction-the-aesthetics-of-online-videos?rgn=main;view=fulltext>, accessed 2 September 2022. In this regard, TikTok’s barrier is arguably much lower than YouTube’s; while the latter’s most popular creators tend to make use of expensive equipment such as video cameras, microphones, lighting and editing software, most necessary TikTok tools are available within the app itself.[15]See Shan Grierson, ‘YouTube Vs. TikTok: Which Is Better for Content Creators?’, Backstage, 8 August 2022, available at <https://www.backstage.com/magazine/article/youtube-vs-tiktok-which-is-better-75397/>, accessed 8 September 2022. There is still room on the platform for professional-standard productions, as Australian TikTok series Love Songs and Scattered have demonstrated;[16]See Kim Munro, ‘Every Minute Counts: TikTok Comes of Age in Scattered’, Metro, no. 211, 2022, pp. 64–7. however, its ease of access allows creators to effectively consider how to incorporate an active audience within their projects.

Remixing media

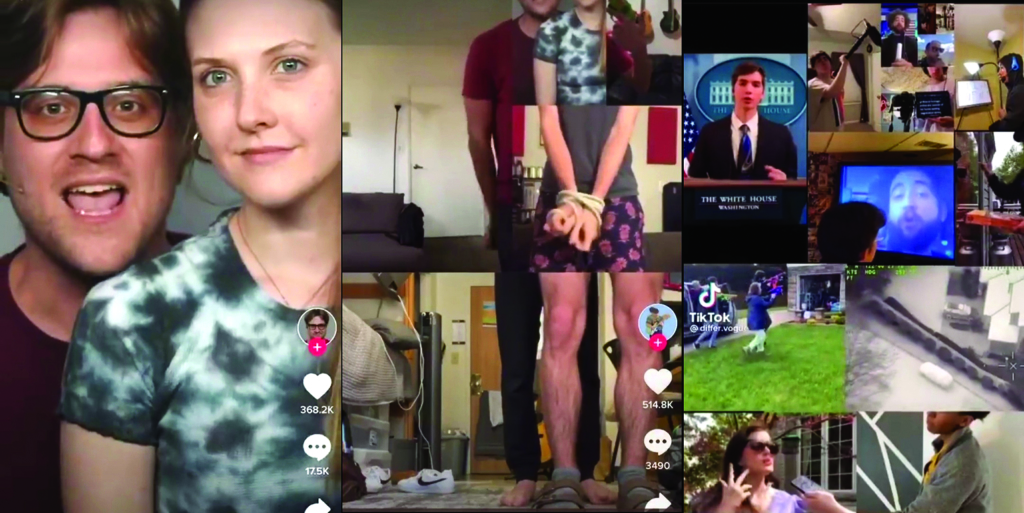

Two key features of TikTok allow users to remix other creators’ ideas: the Stitch tool, which enables a user to take an existing video and cut part of it into their own video response, giving them the opportunity to respond to a very specific moment in the production or to continue adding to the story in their own way; and the Duet function, which projects the original video alongside the response in split-screen format, with users able to position the original video above, beside or below their response.

A sophisticated example of the latter kind of remix trended on the platform in May 2021. In response to a TikTok video of journalist Marcus DiPaola somewhat awkwardly introducing his girlfriend to his followers, other users – likening the clip to a hostage video – first ‘Dueted’ his footage by adding a split-screen on the right of a commensurate arm waving a water pistol at his ‘captive’, then paired that composite with a view beneath supposedly revealing DiPaola’s girlfriend’s arms having been bound with rope, and so on. Each time the video was added to, the shot size became larger and more details were included, from an additional arm and legs to other creators respectively pretending to be a crisis negotiator standing outside with a megaphone, a news anchor reporting on the situation and a viewer at home watching it all unfold on television.[17]See Lydia Veljanovski, ‘Marcus DiPaola Awkward Girlfriend TikTok Video Escalates into Hilarious Hostage Thriller’, Newsweek, 11 May 2021, <https://www.newsweek.com/tiktok-girlfriend-hostage-viral-video-1590429>, accessed 7 September 2022. The complexity of this Duet chain reinforces the virtual-playground nature of the app, and how TikTok stories can be contributed to in ways the original creator may not have intended.[18]While the DiPaola remixes could be interpreted as purely lighthearted and not having been made with any malicious intent, the pile-on effect of TikTok remix chains can have more harmful outcomes for original creators. See Robert McCoy, ‘I’m the TikTok Couch Guy. Here’s What It Was Like Being Investigated on the Internet.’, Slate, 6 December 2021, <https://slate.com/technology/2021/12/tiktok-couch-guy-internet-sleuths.html>, accessed 7 September 2022.

Story structure on TikTok

Analysing the aesthetics of TikTok videos, media researcher Ethan Kurzrock draws on film theorist David Bordwell’s earlier examination of ‘intensified continuity’, or the effects that techniques such as ‘shot duration, camera motion, and visual effects’ have had on visual language in cinema.[19]Kurzrock, op. cit., pp. 1–2. Noting the additional flexibility offered by lightweight cameras, Bordwell points out that such equipment has enabled cinematographers to get closer and cut more frequently, with tighter shots depicting focal areas successively rather than simultaneously (in, for instance, a long single-take wide shot).[20]David Bordwell, ‘Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film’, Film Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 3, Spring 2002, pp. 16-28. Considering Bordwell’s argument in the even more dynamic context of TikTok, Kurzrock asserts that ‘intensified play connects the intensification of contemporary cinematic techniques to the changing characteristics of play on mobile devices’.[21]Kurzrock, op. cit, p. 3. Compared with contemporary filmmaking, shots in TikTok videos are even shorter, and the visual effects that the app provides are more visible. Amateur aesthetics – including the use of jump cuts and the breaking of cinematic conventions such as the 180-degree rule – are often employed by TikTok creators to speed up storytelling within what was, at the time of Kurzrock’s research, a maximum running time of one minute.[22]As of February 2022, TikTok videos can now be up to ten minutes in length (the previous increase, from one to three minutes, occurred in July 2021). See Todd Spangler, ‘TikTok Bumps Up Max Video Length to 10 Minutes’, Variety, 28 February 2022, <https://variety.com/2022/digital/news/tiktok-maximum-video-length-10-minutes-1235191773/>, accessed 7 September 2022.

It’s important that viewers are hooked by the first few seconds of a video … while a surprising finale will increase the likelihood of a rewatch or other forms of passive audience engagement.

Another filmmaking convention Kurzrock discerns in TikTok videos is a more simplified version of the traditional three-act structure, in this context usually incorporating a thrilling beginning and a surprise conclusion.[23]Kurzrock, op. cit., p. 7. The platform itself advocates for this approach as a means of creating successful content: in the website’s ‘creator portal’, TikTok users are encouraged to include ‘a beginning, a middle, and an ending’ in their videos.[24]See ‘Elements of a TikTok Video’, TikTok website, <https://www.tiktok.com/creators/creator-portal/en-us/tiktok-creation-essentials/elements-of-a-tiktok-video/>, accessed 19 June 2022. Because the ‘For You’ feed automatically plays video suggestions, it’s important that viewers are hooked by the first few seconds of a video and that the following act maintains audience engagement, while a surprising finale will increase the likelihood of a rewatch or other forms of passive audience engagement – thus increasing a video’s reach. This structure can be applied not only to standalone videos but also to individual episodes of a web series, though the depth of each act will be dependent on running time.

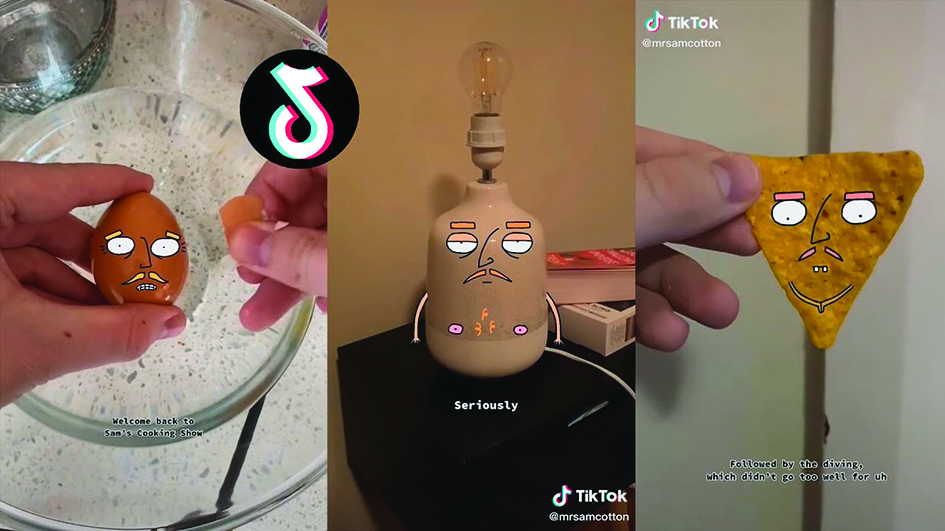

• Watch three different TikTok videos: the first episode of a web series (e.g. Scattered[25]See Scattered Series TikTok post dated 17 May 2021, <https://www.tiktok.com/@scatteredseries/video/6963103929118854402>, accessed 7 September 2022.); a standalone production (e.g. one of Sam Cotton’s short videos of animals and everyday objects enhanced by hand-drawn animation and comedic voiceover[26]See, for example, Sam Cotton TikTok post dated 6 December 2020, <https://www.tiktok.com/@mrsamcotton/video/6902884988484652290>, accessed 7 September 2022.); and a simple home movie (e.g. Gordon Ramsay’s daughter Tilly pranking him with a water bottle[27]See tillyramsay TikTok post dated 18 March 2021, <https://www.tiktok.com/@tillyramsay/video/6940704505692491013>, accessed 7 September 2022.). Identify the ‘beginning’, ‘middle’ and ‘end’ of each video, taking note of how they differ, and discuss the effectiveness of their respective opening hooks.

• Consider the above videos’ respective genres, and how the three-act structure is used to construct a story in under a minute.

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘Digital 2022 Australia: Online Like Never Before’, We Are Social website, 9 February 2022, <https://wearesocial.com/au/blog/2022/02/digital-2022-australia-online-like-never-before/>, accessed 18 June 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Kim Lyons, ‘TikTok Says It Has Passed 1 Billion Users’, The Verge, 27 September 2021, <https://www.theverge.com/2021/9/27/22696281/tiktok-1-billion-users>, accessed 2 September 2022. |

| 3 | See Elena Cresci, ‘Lonelygirl15: How One Mysterious Vlogger Changed the Internet’, The Guardian, 16 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/16/lonelygirl15-bree-video-blog-youtube>, accessed 2 September 2022. |

| 4 | See The Lizzie Bennet Diaries YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/user/LizzieBennet/videos>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 5 | See Marble Hornets YouTube channel, <https://www.youtube.com/user/MarbleHornets/videos>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 6 | See ‘Who Killed Markiplier? – Chapter 1’, YouTube, 11 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YoSrocwNYjA>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 7 | Henry Jenkins, in ‘Henry Jenkins – What Is Media Convergence?’, YouTube, 17 May 2012, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFbJCdCoNIc>, accessed 2 September 2022. |

| 8 | See Ben Child, ‘Sickhouse: How the First Ever Snapchat Movie Redefined Viral’, The Guardian, 23 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/22/sickhouse-how-the-social-media-horror-film-went-viral>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 9 | See Isabel Kershner, ‘A Holocaust Story for the Social Media Generation’, The New York Times,30 April 2019, <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/30/world/middleeast/eva-heyman-instagram-holocaust.html>, accessed 19 June 2022. |

| 10 | See Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964, pp. 7–23. |

| 11 | Ben Smith, ‘How TikTok Reads Your Mind’, The New York Times,5 December 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html>, accessed 17 June 2022. |

| 12 | See Caroline Klidonas TikTok account, <https://www.tiktok.com/@carolineklidonas>, accessed 2 September 2022. |

| 13 | See Ethan Kurzrock, ‘Intensified Play: Cinematic Study of TikTok Mobile App’, self-published, April 2019, pp. 4–5, available at <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335570557_Intensified_Play_Cinematic_study_of_TikTok_mobile_app>, accessed 12 June 2021. |

| 14 | Stephen Groening, ‘Introduction: The Aesthetics of Online Video’, Film Criticism, vol. 40, no. 2, June 2016, available at <https://quod.lib.umich.edu/f/fc/13761232.0040.201/–introduction-the-aesthetics-of-online-videos?rgn=main;view=fulltext>, accessed 2 September 2022. |

| 15 | See Shan Grierson, ‘YouTube Vs. TikTok: Which Is Better for Content Creators?’, Backstage, 8 August 2022, available at <https://www.backstage.com/magazine/article/youtube-vs-tiktok-which-is-better-75397/>, accessed 8 September 2022. |

| 16 | See Kim Munro, ‘Every Minute Counts: TikTok Comes of Age in Scattered’, Metro, no. 211, 2022, pp. 64–7. |

| 17 | See Lydia Veljanovski, ‘Marcus DiPaola Awkward Girlfriend TikTok Video Escalates into Hilarious Hostage Thriller’, Newsweek, 11 May 2021, <https://www.newsweek.com/tiktok-girlfriend-hostage-viral-video-1590429>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 18 | While the DiPaola remixes could be interpreted as purely lighthearted and not having been made with any malicious intent, the pile-on effect of TikTok remix chains can have more harmful outcomes for original creators. See Robert McCoy, ‘I’m the TikTok Couch Guy. Here’s What It Was Like Being Investigated on the Internet.’, Slate, 6 December 2021, <https://slate.com/technology/2021/12/tiktok-couch-guy-internet-sleuths.html>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 19 | Kurzrock, op. cit., pp. 1–2. |

| 20 | David Bordwell, ‘Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film’, Film Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 3, Spring 2002, pp. 16-28. |

| 21 | Kurzrock, op. cit, p. 3. |

| 22 | As of February 2022, TikTok videos can now be up to ten minutes in length (the previous increase, from one to three minutes, occurred in July 2021). See Todd Spangler, ‘TikTok Bumps Up Max Video Length to 10 Minutes’, Variety, 28 February 2022, <https://variety.com/2022/digital/news/tiktok-maximum-video-length-10-minutes-1235191773/>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 23 | Kurzrock, op. cit., p. 7. |

| 24 | See ‘Elements of a TikTok Video’, TikTok website, <https://www.tiktok.com/creators/creator-portal/en-us/tiktok-creation-essentials/elements-of-a-tiktok-video/>, accessed 19 June 2022. |

| 25 | See Scattered Series TikTok post dated 17 May 2021, <https://www.tiktok.com/@scatteredseries/video/6963103929118854402>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 26 | See, for example, Sam Cotton TikTok post dated 6 December 2020, <https://www.tiktok.com/@mrsamcotton/video/6902884988484652290>, accessed 7 September 2022. |

| 27 | See tillyramsay TikTok post dated 18 March 2021, <https://www.tiktok.com/@tillyramsay/video/6940704505692491013>, accessed 7 September 2022. |