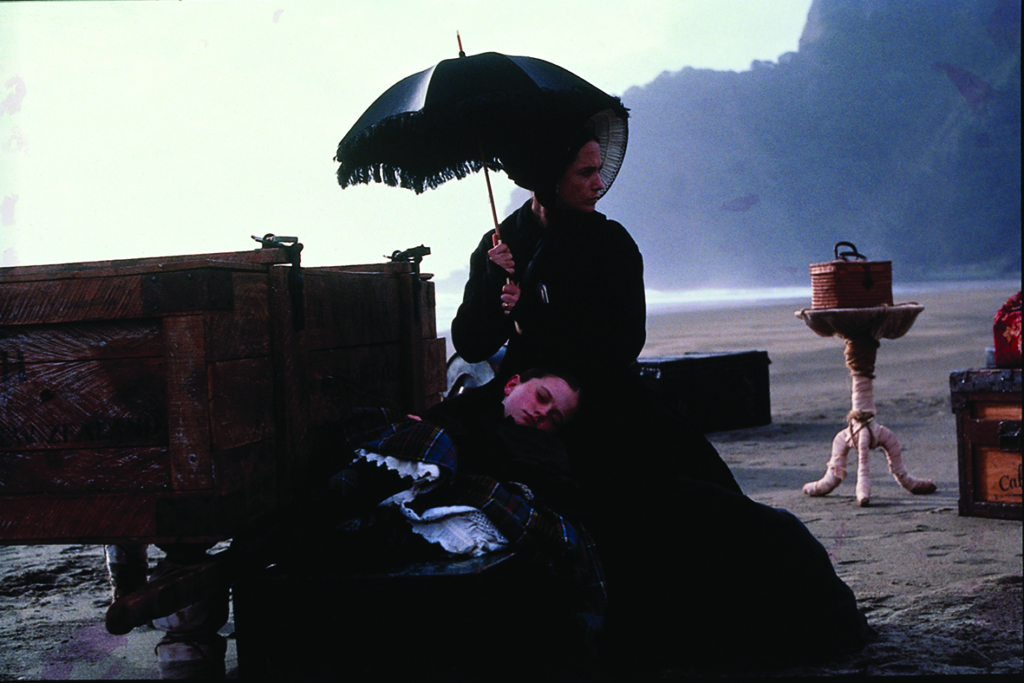

On a beach in remote New Zealand, an unstoppable tide surges towards a large shipping crate that contains a piano. Its owner, Ada (Holly Hunter), looks on in horror from a nearby cliff as she’s forced to walk away from the instrument through which she, an elective mute, is able to express herself. Michael Nyman’s rousing composition ‘The Promise’ plays as Ada watches waves creep closer to her piano. At the end of the film, Ada forces her lover Baines (Harvey Keitel) to throw her ‘spoiled’ piano into the ocean as they journey by boat to their new home in Nelson. Slipping her foot into the coiled rope that trails the sinking instrument, Ada sees herself pulled in after it. Her large black dress billows underwater, her arms go slack and her hair swirls with the tide. For a moment, Ada and her piano are together in their ‘ocean grave’.

In another story, in another time, but in the same ocean, a turquoise suitcase burps air, bouncing off rocks, sinking to the sea floor after being pushed off a cliff. The contents of the suitcase are a mystery. Soon, it rises slowly: First, with a ribbon of black hair streaming through a crack in the suitcase. Then, with a trail of bubbles, the suitcase lifts itself steadily – like someone standing up – until it finds air, bobbing to the surface. Fifty minutes of screen time later, waves the same colour as the case push it towards the beach, where lifeguards drag it ashore. Another five minutes of screen time later, detective Robin Griffin (Elisabeth Moss) opens the suitcase and whispers to the body inside, ‘Hello, darling. Want to tell me what you saw?’

The stories of silent women ebb and flow with the tide. Eventually, though, they rise.

Women’s stories

These two texts – both written and directed by Jane Campion[1]Though, on China Girl, Campion shares writing credits with Gerard Lee and directing credits with Ariel Kleiman. – seem, at first glance, quite different.

The first, The Piano (1993), is set in nineteenth-century New Zealand and tells the story of the silent Ada, who has landed there from Scotland with her young daughter, Flora (the breakout role for a tiny Anna Paquin), as part of an arranged marriage. New husband Stewart (Sam Neill) is blunt, forceful and, at times, cruel upon their arrival, leaving Ada’s beloved instrument on the beach despite her insistence that it be carried to their inland home. Stewart’s neighbour Baines eventually purchases the piano, then enters into a sexual arrangement with Ada under the guise of piano lessons, promising that she can earn her instrument back by allowing him to do what he wants to her as she plays.

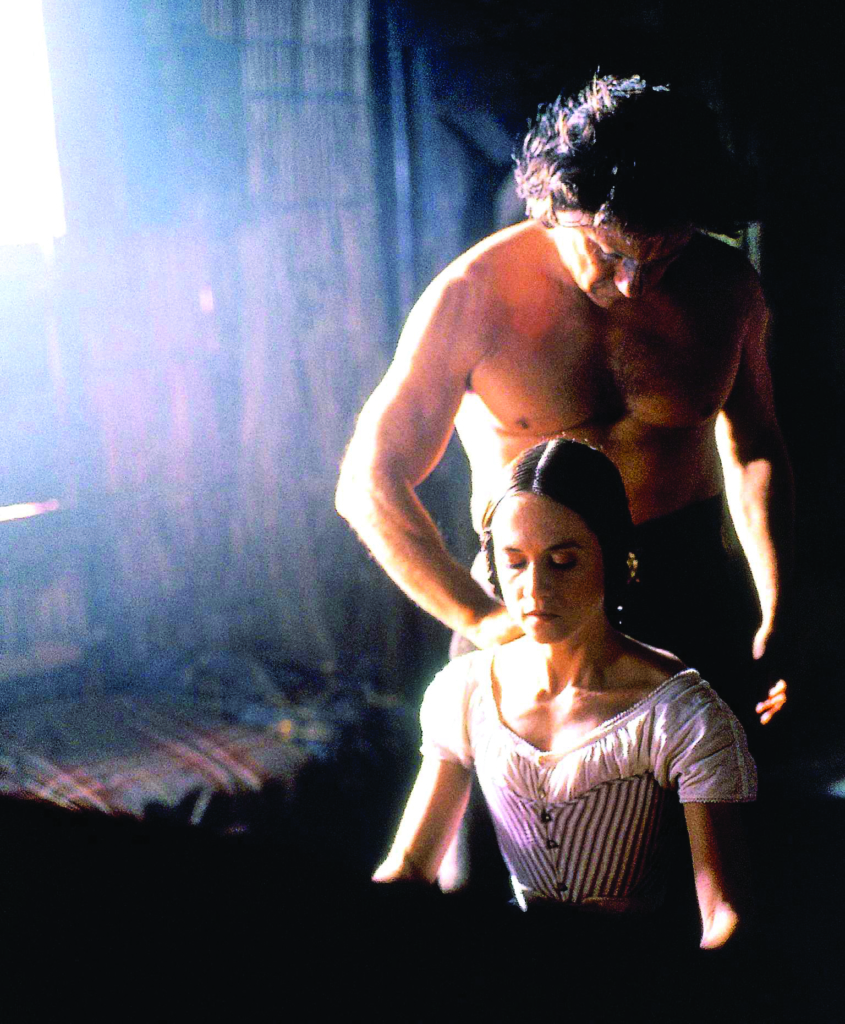

Their relationship continues even after Baines has returned the piano to her and decided that ‘the arrangement is making [her] a whore, and [him], wretched’. What unfolds between them is a quest for erotic fulfilment, particularly for the otherwise-powerless Ada. Stewart discovers the pair’s secret, however, and punishes Ada, chasing her down through the bush and assaulting her, before using an axe to cut off one of her fingers – robbing her of her ability to play the piano. In the end, Ada and Flora move to Nelson together with Baines, leaving Stewart, the failed marriage and all that pain behind.

The second, Top of the Lake: China Girl, is the follow-up season of a crime drama with Robin at its centre. The detective has returned to her home town of Sydney still processing the shooting of a co-worker as well as her ongoing trauma from having been gang-raped as a teenager and becoming pregnant as a result. There, she makes contact with her biological daughter, Mary (Alice Englert), while working on the case of the girl in the suitcase (‘China Girl’), and finds the two horrifically connected through Mary’s manipulative older boyfriend, ‘Puss’ (David Dencik).

What links The Piano to China Girl most obviously is the involvement of Campion – hailed as ‘Australasia’s leading auteur director’[2]Fincina Hopgood, ‘Jane Campion’, Senses of Cinema, issue 22, October 2002, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/campion/>, accessed 19 February 2018. – whose career is long and accomplished, and who is well known for her skilful use of landscape and setting, dark humour, and nuanced centring of women’s stories. But, more deeply than this, both texts offer case studies of Campion’s ongoing preoccupations. While an erotic, Gothic period drama might seem worlds away from a modern-day crime drama, there are underlying themes tying the two together, to the extent that they can almost be viewed as (unlikely) mirror texts.

Feminist film scholar Karen Hollinger suggests that the ‘woman’s film’ genre is ‘defined by the centrality of its female protagonist, its attempt to deal with issues deemed important to women and its address to a female audience’. Building on the work of Mary Ann Doane, she identifies four subcategories of this cinematic categorisation:

the maternal melodrama (focusing on a mother’s joys and tribulations), the love story (concentrating on the vicissitudes of heterosexual romance), the medical discourse film (with its focus on a physically or mentally ill woman) and the paranoid gothic thriller (centred on a wife’s fear of her husband’s possibly murderous designs on her).[3]Karen Hollinger, ‘From Female Friends to Literary Ladies: The Contemporary Woman’s Film’, in Steve Neale (ed.), Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, British Film Institute, London, 2002, p. 78.

While the label ‘woman’s film’ might now seem a little outdated, it’s nevertheless a useful lens through which to analyse Campion’s work; indeed, there are elements of all four of Hollinger’s subgenres in both The Piano and China Girl. Of the two, The Piano is more easily read as a woman’s film: it’s a period piece told from the perspective (and using the voiceover) of a vulnerable woman whose body is traded as a commodity, but who ultimately wrests power for herself. Yet China Girl similarly has a focus on the claiming of power by women whose bodies are under the control of men who harbour ‘possibly murderous designs’ on them. Campion herself has described The Piano as ‘a gothic exploration of the romantic impulse’.[4]Jane Campion, quoted in Andrew L Urban, ‘Making of: The Piano (1993)’, Urban Cinefile, 3 August 1993, <http://www.urbancinefile.com.au/home/view.asp?a=1512>, accessed 19 February 2018. Using Hollinger’s conception of fear of the murderous husband as a common element of Gothic woman’s films, then, ‘gothic exploration of the romantic impulse’ could equally apply to China Girl. The sex workers at the Silk 41 brothel, in particular, face constant peril from the bodily vulnerability of illegal surrogacy, sex work and Puss’ insistence on seizing women’s agency. Sending her out to work the street alone, Puss takes from Mary the small vestige of power she once had within this relationship with an older, criminal man. Only when it’s too late does she fully understand his ‘possibly murderous designs’ on her.

Similarly, both The Piano and China Girl feature vulnerable women mirrored by their even more vulnerable daughters: Flora’s bonneted head, outfits and facial expressions all mimic those of her mother; Robin and Mary’s matching volatility and precocious maturity make them seem more like sisters. Family dynamics are central to both the film and the series, as unconventional families with women at their centres attempt to join, break apart, rejoin and reconfigure towards something hopeful and safe. Ada and Flora are forced into life with Stewart, but eventually end up with the gentler and more attentive Baines. Mary and Robin attempt to build their own relationship as friends, while Mary pushes as hard as she can against her adoptive mother, Julia (Nicole Kidman). A sexual encounter between Mary’s adoptive father, Pyke (Ewen Leslie), and Robin shifts the family dynamic again. In the end, Robin and Mary silently acknowledge a new way of being a family, with Mary under the care of her adoptive parents and her ongoing relationship with Robin left ambiguous but on good terms.

Aspects of the ‘medical discourse’ film can be seen in the two works, too. While neither Ada nor Mary are explicitly diagnosed with any mental illness, the speculation of those around them pathologise Ada’s muteness (Stewart wonders ‘if she’s not brain-affected’) and Mary’s volatility (Julia suggests ‘it would be better if she was in the hospital […] she could have bipolar, schizophrenia – we know nothing about her birth mother’).

But, ultimately, central to both texts are the power dynamics within eroticism: Gothic elements blurring with romance to create a narrative that is at once dangerous and compelling. In The Piano, we see how Ada’s fate is inextricably tied to the decisions and actions of the well-meaning – but ultimately paternalistic – Stewart and Baines; all the while, the strangeness of New Zealand’s landscape provides a menacing backdrop for the story. In China Girl, menace comes primarily from the presence of outwardly dangerous men and their drive to control women. As Puss tells Julia, he believes that ‘the destiny of man is to enslave women’, in much the same way that Stewart seems to expect his arranged marriage to service his needs only.

Strong female characters

A more modern conception of central roles for women in film is that of the ‘strong female character’, which normalises the presence and concerns of women as being of universal appeal, and goes beyond a filmic category pitched only to a portion of audiences. The trope immediately brings to mind Game of Thrones’ Brienne of Tarth – the most well-known screen role of Gwendoline Christie, who stars in China Girl as the cop Miranda – whose strength comes from her ability to inhabit the masculine in a mode similar to men.

Despite their bodily fragility, it’s temptingly simple to view Ada, Robin and Mary as ‘strong women’. Ada’s ferocity sits in her brow, in her dark eyes, in the urgency with which she communicates emotion as she signs – and in her immovability in the face of her husband’s violence. She is best described as wilful, attested to in her own voiceover (‘My will has chosen life’) and in the words Stewart believes he has heard her utter to him (‘I am afraid of my will – of what it might do’). Robin’s own wilfulness sees her constantly fight back against bad men despite the very real dangers they pose. And Mary fiercely pursues the relationship she wants with Puss, ignoring her parents’ concerns. Over dinner, she tells her mother that she’s not a feminist and, throughout the series, her moving in and out of the family home is very much on her own terms.

These women are ‘strong’, yes, but Campion’s telling of women’s stories is more complex than what is allowed by a simplistic designation; she is more knowing than to portray female characters as strong and strong alone. By way of comparison, male characters are often not confined to ‘strength’ – in the words of New Statesman’s Sophia McDougall, ‘They’re used to being interesting across more than one axis and in more than two dimensions.’[5]Sophia McDougall, ‘I Hate Strong Female Characters’, New Statesman, 15 August 2013, <https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2013/08/i-hate-strong-female-characters>, accessed 19 February 2018. The deep dive that both The Piano and China Girl take with regard to depicting women’s lived experiences (with the possible exception of Christie’s Miranda, who is undersold as endearing but sadly comical) renders them three-dimensional, even more sophisticated than the strangeness of the Gothic aesthetic or the dream and nightmare sequences.

In The Piano, Ada sends her daughter back through the New Zealand bush in order to chase after her lover. Selfishness acts as Ada’s motivator for much of the film, but ascertaining and getting what she wants aren’t necessarily straightforward wins. Ada’s sexual becoming isn’t simply a victory in the face of Victorian-era sexual repression; rather, as film critic Joanna Di Mattia puts it,

Ada, Baines, and Stewart each engage with touch in different ways. In particular, the economy of touch between Ada and Baines explores how sexual desire between women and men is a bargain in which power relations are repeatedly renegotiated over shifting ground.[6]Joanna Di Mattia, ‘The Heart Asks Pleasure First: Economies of Touch and Desire in Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993)’, Senses of Cinema, issue 84, September 2017, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2017/cteq/the-piano>, accessed 19 February 2018.

The Piano emphasises this nuance and, at its conclusion, the viewer isn’t entirely sure whether they’re happy for Ada or not – particularly with so little consideration given to Flora’s fate or wellbeing. The film ends on a minor key.

In China Girl, Mary isn’t a consistently likeable character. Her blind defence of Puss puts her in deeper and deeper danger – and, while her tender-hearted nature makes her easy to love, her innocence and occasional violence make her a character that actress Englert has described as monstrous: ‘a person who doesn’t always make sense and wasn’t even making sense to herself’.[7]Alice Englert, quoted in Andrew Taylor, ‘Top of the Lake: China Girl: How Jane Campion Turned Alice Englert into a Monster’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 2014, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/top-of-the-lake-china-girl-how-jane-campion-turned-alice-englert-into-a-monster-20170804-gxpjiq.html>, accessed 19 February 2018. In a similar vein, Robin’s own needs get in the way of her ability to act as the birth mother Mary has been seeking – if, indeed, there was ever a ‘right’ way for her to do such a thing. Her ability to deal with physical aggression shows (stereotypical) strength, and the casting of Moss does, of course, bring with it an intertextual nod towards the now-iconic walkout of Peggy Olson in Mad Men’s ultimate ‘strong female’ moment. However, what makes Robin human is her fallible womanhood. She struggles in interpersonal relationships, is constantly outrunning her trauma and, at times, makes terrible decisions.

*

A key difference between The Piano and China Girl is the state of feminism outside the texts themselves. While, in 1993, a period drama was arguably considered of interest to women only, a female detective at the centre of a 2017 crime drama offers appeal across a large and varied audience, regardless of gender.

With 2018 marking twenty-five years since the release of the earlier text, it is timelier than ever to revisit Campion’s filmic and political predilections. Her oeuvre is known for its seasoned aesthetic and portrayal of women’s stories as significant, three-dimensional and nuanced. Over her decades-long career, Campion has collected multiple awards, including at the Oscars, the AACTAs and the Venice International Film Festival, along with the Cannes Film Festival’s coveted Palme d’Or for The Piano. While this film has created a high watermark for the director, the critical reception of her work across the years has certainly fluctuated – China Girl itself was received less favourably than the series’ first season. In spite of that, Campion’s sensibility and preoccupations give her work a certain steadiness. Moving beyond the contemporary trend of ‘strong female characters’, her women are relatable (for better or worse), emotionally truthful and relevant. While The Piano and Top of the Lake: China Girl might seem like vastly different texts, these currents tie the two together.

Endnotes

| 1 | Though, on China Girl, Campion shares writing credits with Gerard Lee and directing credits with Ariel Kleiman. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Fincina Hopgood, ‘Jane Campion’, Senses of Cinema, issue 22, October 2002, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/campion/>, accessed 19 February 2018. |

| 3 | Karen Hollinger, ‘From Female Friends to Literary Ladies: The Contemporary Woman’s Film’, in Steve Neale (ed.), Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, British Film Institute, London, 2002, p. 78. |

| 4 | Jane Campion, quoted in Andrew L Urban, ‘Making of: The Piano (1993)’, Urban Cinefile, 3 August 1993, <http://www.urbancinefile.com.au/home/view.asp?a=1512>, accessed 19 February 2018. |

| 5 | Sophia McDougall, ‘I Hate Strong Female Characters’, New Statesman, 15 August 2013, <https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2013/08/i-hate-strong-female-characters>, accessed 19 February 2018. |

| 6 | Joanna Di Mattia, ‘The Heart Asks Pleasure First: Economies of Touch and Desire in Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993)’, Senses of Cinema, issue 84, September 2017, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2017/cteq/the-piano>, accessed 19 February 2018. |

| 7 | Alice Englert, quoted in Andrew Taylor, ‘Top of the Lake: China Girl: How Jane Campion Turned Alice Englert into a Monster’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 2014, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/top-of-the-lake-china-girl-how-jane-campion-turned-alice-englert-into-a-monster-20170804-gxpjiq.html>, accessed 19 February 2018. |