Melrose Place is a television phenomenon: a show that’s talked about and written about as much as it is watched. References to it abound: Winona Ryder’s character, in the film Reality Bites, insists, always to much audience hilarity, “Melrose Place is a really good show.” There’s a computer network conference exclusively for discussion of Melrose Place episodes, with a running tally on the number of underwear sequences in the show. A Melbourne bar devotes Tuesday nights to the soap, so that patrons can drink cocktails and keep up with the latest traumatic plot twist featuring the most incident-prone piece of real estate since Towering Inferno. There are oft-quoted reports of Melrose Place dinner parties, with discussions of the latest episode over coffee, or more informal get-togethers for Coke, CCs and an in-depth analysis of who is more of a loser: Jane, the divorced wife of the fiendish Michael Mancini, who seems to have a capacity for forgiveness on a level with that of Mother Theresa, but only where her ex is concerned; or Alison, the perky, goody-goody who seems blithely oblivious to the sexual interest male characters have in her, even when they are crazed psychopathic stalkers.

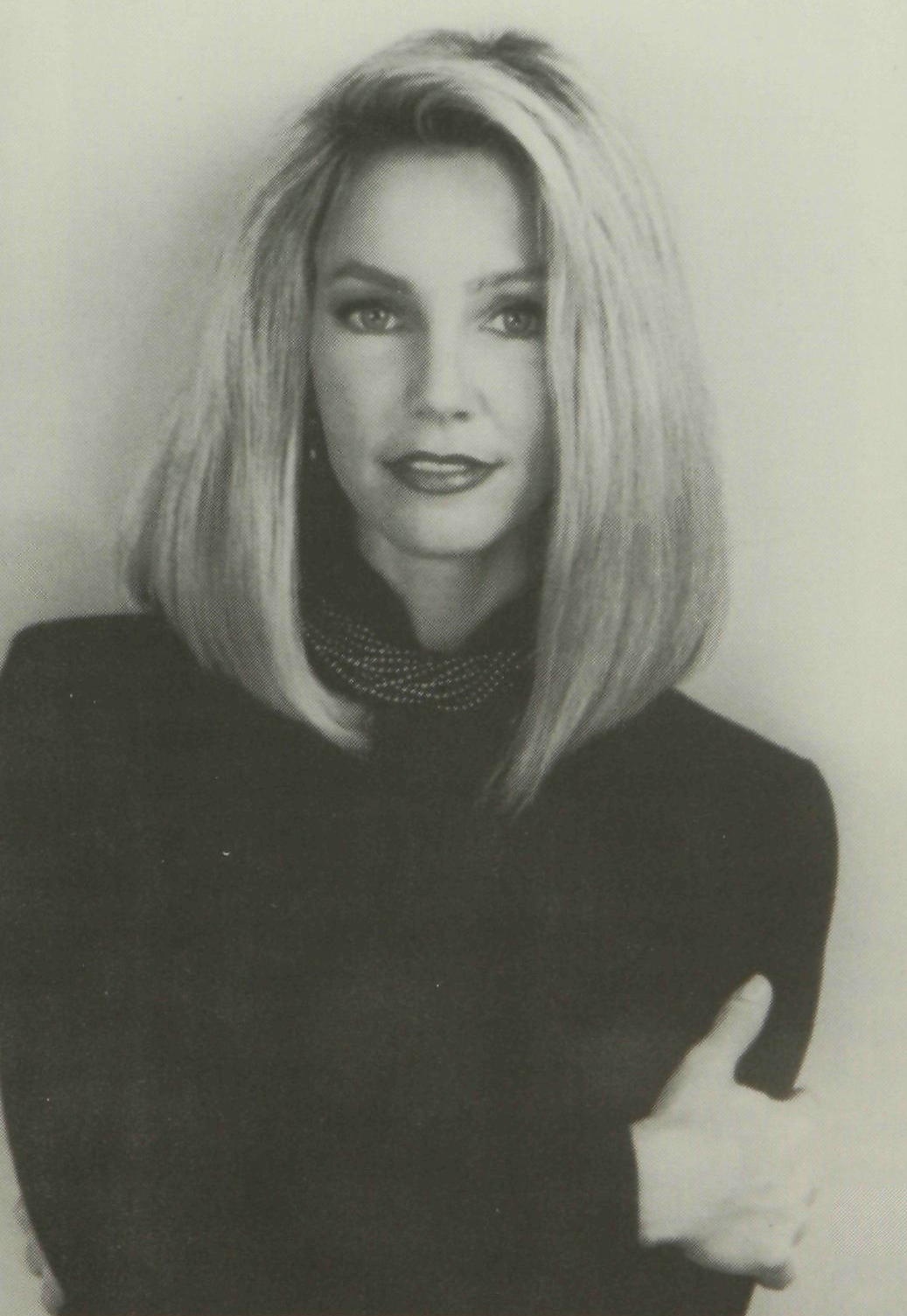

The media love this kind of show, particularly soft-centred Nineties media: it’s television as event, the soap as social phenomenon, coupled with the gossipy glamor of high-class trash culture. Comparisons with the Eighties Dynasty and Dallas phenomenon recur: Melrose Place star Heather Locklear is hailed as the Alexis of the Nineties, and the scheming Michael Mancini (Thomas Calabro) is the J.R. Ewing. The female cast members line up, in skimpy white outfits, for a fold-out ‘Rolling Stone’ cover, and a story entitled ‘Melrose Place’s Bod Squad’. The male cast members are proclaimed as examples of a new phenomenon – the male bimbo, or “himbo”. Magazines and newspapers can run chatty items about the stars of the show and psychological/sociological analysis of the show’s popularity, particularly among the over-20s.

Melrose Place was targeted at just that group: the key 19–49 adult demographic. It began as an older relative of the hugely popular teen series Beverly Hills 90210: the shows share a creator, Darren Star, and executive producer, TV veteran Aaron Spelling. Explicit links between the two were made: the character of biker Jake (Grant Show) was introduced into episodes of 90210 as a pal to Brandon (Jason Priestley); then Kelly (Jennie Garth) from 90210 spent five episodes hanging out at Melrose Place, lusting helplessly after Jake.

For the Fox Network, the program was an important test, a significant part of the company’s plans to expand from a five to a seven-day schedule. It needed a positive reception – not with critics but with audiences. Its US debut, with 16 million viewers, seemed more than promising: Fox chairman and chief executive officer Rupert Murdoch rang Spelling after the premiere to congratulate him.

Melrose Place was poised between the teen angst of 90210 and the domestic and professional traumas of the ‘thirtysomething’ generation. Eight characters from different backgrounds were put together in an apartment block in a chic suburb of Los Angeles – a pink, Spanish mission-style building with a communal swimming pool. The location was stylish, but the show started out with a proclaimed sense of social responsibility: its founding tenants included a black character and a gay male character. Spelling said that the often-criticised ethnic homogeneity of 90210 was not going to be a feature of Melrose Place.

The problems of young, ambitious, career-minded people were meant to be the staple of the show: relationship traumas, crises at work, financial problems. Sex was definitely going to be an ingredient: it was easier to incorporate into the storyline than it had been in 90210. But the producers also promised hard-edge storylines: “abortion, sexual harassment, inter-racial dating and the effect of the current economic hard times on the Melrose generation”. It was suggested that with a gay character, issues such as outing and gay-bashing would be explored.

But there were mixed messages about the show from the very beginning, neatly encapsulated by the opening titles. They are a cross between a rock clip and an advertisement for imported beer or liqueur. They show us grainy images of street life – leached of colour at some points, neon-bright at others – in that blurry, hand-held, home-movie style that is a sophisticated cliche. Then we are gradually introduced to the cast, shown mostly in the same deliberately raw style: candid close-ups, smiling flirtatiously or knowingly into the camera, as if the characters had shot the opening titles themselves. In between is a different kind of footage: brief carefree ensemble sequences, and, immaculately lit and framed, sharp images of the show’s designated hunk, Jake, first leather-jacketed and then bare-chested. The program itself had none of these visual qualities: the smooth surface of prime-time TV swiftly returned.

The ratings for the first series, however, were fairly lacklustre, after a strong start: the formula didn’t seem to be working. There were various reasons put forward for this among the Melrose Place creative team. The show was not originally envisaged as a prime-time soap opera, and episodes were self-contained: the consensus seemed to be that this made it more difficult to sustain viewer interest. Two characters seen to be “going nowhere in plot terms” were dumped: Rhonda, the black aerobics instructor (Vanessa Williams), who was the beginning and end of the show’s ethnic mix; and Sandy Louise (Amy Locane) the aspiring actress with the erratic Southern accent, who had – like virtually every female character in the series – a brief fling with Jake.

It was decided that the ‘90210’ link was hindering, rather than hurting, the show: it was thought necessary to reinforce a more adult image. The characters’ emotional dilemmas were deemed too dull: more extreme, intense storylines were called for.

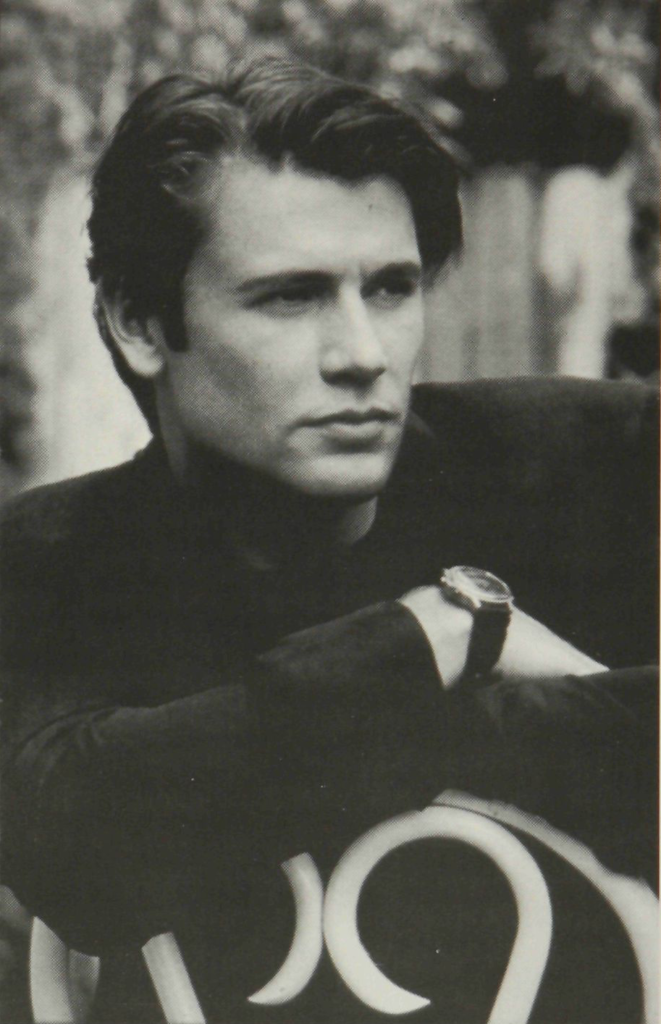

It was also found, to the producers’ surprise, that Billy (Andrew Shue) was more appealing to female viewers than Jake. Shue was a late replacement in the show: actor Stephen Fanning was originally cast as Billy, and replaced shortly after filming started – he even appeared in some of the early publicity shots. Billy is an aspiring writer who supported himself, in the early stages of the series, by working as a ballroom dancing instructor, later as a cab driver. While Jake was a biker hunk, Billy was more of a sensitive, considerate type – his muscle tone, however was more than a match for Jake’s. He and Alison (Courtney Thorne-Smith) were platonic flatmates for some time, and the sexual tension between them generated a certain amount of viewer interest.

They finally became lovers: but it wasn’t until the arrival of Amanda, the woman who came between them, that Melrose Place started to develop a significant following. Clearly, the show was already being revamped, and Heather Locklear, who played Amanda, was part of the process – but the publicity plays up her role in bringing a new audience to Melrose Place. Locklear had a soap track record as the wicked Sammy-Jo in Dynasty: she joined Melrose Place for four episodes, as Alison’s boss at the advertising agency. Her character also had an affair with Billy. When it was decided to make Locklear a permanent cast member, Amanda moved into Melrose Place, bought the block and became queen bee of the building. According to Spelling: “What we had was a very interesting but passive group. We needed Heather to stir the pot.”

Amanda is, in Melrose Place terms, an older woman – Locklear is 32. She’s not a straightforward villain, like Michael: she is capable of acts of generosity and altruism, as well as aggressive, self-interested feats of manipulation. She represents power, with her ownership of the building and senior position in her workplace. All the other Melrose Place inhabitants are on their way up. Alison began in the advertising agency as a receptionist before beginning to handle accounts. Billy was taking odd jobs to support his ambitions as a writer. Jake is a jack of all trades, and not particularly ambitious. Michael, the doctor, began the series as a hospital intern, and caretaker of the block. His wife Jane (Josie Bissett), an aspiring fashion designer, worked as a sales assistant. Matt (Doug Savant), the gay character, began the series as a social worker in a shelter for homeless youth. Jo (Daphne Zuniga), the other new tenant in the building, is a freelance photographer who left New York and a failed marriage to seek her fortune in the West.

All these characters underwent changes as the new “hot” Melrose Place was born, with a more adult image, ongoing storylines and more emphasis on sexual liaisons (except for Matt). Social issues, despite the promises, had never been a particularly prominent feature of the program in the first place – the black character was disposed of quickly, and Matt functioned mainly as a confidant to the female tenants.

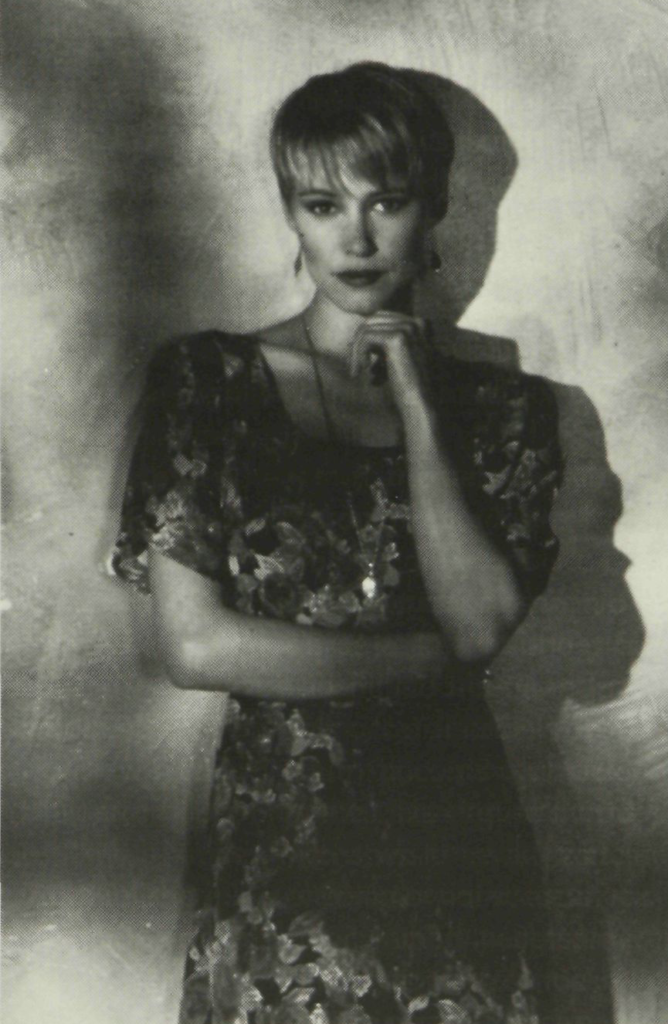

The most fundamental character change was that given to Michael Mancini, the young intern from Chicago who initially found Los Angeles an alienating place. Michael and Jane were the only married couple in the building: their marriage broke down when Michael began to have an affair at the hospital with a fellow-doctor, Kimberly Shaw (Marcia Cross). At first, this seemed like a straightforward infidelity; but it heralded a significant shift in Michael’s personality. He became manipulative, selfish and arrogant: a caricature villain who revelled in his selfishness and hypocrisy.

A new female character arrived: Jane’s sister Sydney (Laura Leighton). She had been obsessed with Michael for a long time: he began an affair with her while continuing his relationship with Kimberly. Sydney is an interesting figure: a manipulative woman who is a mixture of naivete and cunning. She suffers reversals and humiliations – particularly when she becomes involved, at first unwittingly, in a prostitution ring, a storyline borrowed from the contemporary Heidi Fleiss scandal which was making headlines in Hollywood. While Amanda always seems to retain control, Sydney lurches from triumph to abjection – she is often physically brutalised. She is a figure whose function is to be damaged, as well as to be damaging.

Melrose Place became successful by building up the power and impact of its female characters, its Sydneys and its Amandas, but it also increased the abuse, threats and danger to which they were subjected. Jo and Alison, in particular, became targets for psychotic males. It also heightened the competitiveness between women: sometimes it resembled a parodic amplification of the notorious Libra Fleur tampon advertising campaign, that narrative of friendship and betrayal, two-timing and commitment, secrets and confessions, with an untrustworthy blonde at the centre.

It has become more self-consciously melodramatic, revelling in its own excesses. In the first series, Jake discovered that he had a son: an ex-girlfriend had become pregnant by him, but kept it a secret. She was now informing him only to ask him to renounce his parental rights, so that her new husband could adopt the boy. At that stage of Melrose Place, the most poignantly dramatic moment took place when Jake discovered that the boy shared his liking for mayonnaise on French fries – the kid was his son after all, even if the boy was unaware of his existence. If such a plot were developed in the new series, it would be much more extreme: the new husband would be a psychopath, and the child would be a pyromaniac, a close personal friend of Michael Jackson, or the member of a kindergarten class which practised satanic rituals before play lunch.

Melrose Place has brought characters “back from the dead”: Kimberly, Michael’s lover, apparently died in a car accident in which he was the driver. She returned, however, transformed: she took her place back in Michael’s life, but as his villainous equal, bent, ultimately, on revenge. Marcia Cross plays her as a rejuvenated figure, revelling in her new wicked status, arch, cutting and confident. Her gradual reappearance – stalking Michael, before she revealed herself – was heralded with an almost Gothic, over-the-top visual style. From being a lightweight Other Woman , Kimberly has been remade on a grand scale, as an emblematic character from a Jacobean revenge tragedy, a Californian Vindice.

The show has successfully targeted a young demographic group, with a set of characters younger than those in Dallas or Dynasty. University of Sydney associate lecturer in the department of psychology Janette Perz suggests in The Australian that Melrose Place is popular with the 20-plus age-group “because it is helping them to define their sense of self. Social comparison is fundamental to their perception of themselves. They need to look at what others are doing, then judge to see whether thoughts and actions are appropriate, to see whether they’ve been doing the same sort of things.”

It functions as a kind of pantomime, where the actions of its characters are greeted with cheers and (much more often) boos, vocal abuse normally meted out to a carnival villain or a football umpire. But it is of its decade, in that its power games are personal: the characters don’t belong to an entrepreneurial class or caste, like Dallas or Dynasty, and they don’t seek business or political control of others. They are not, broadly speaking, acquisitive. The battleground is sexual – power is conceived of in terms of relationships. The current series recently ended with Kimberly’s plans for retribution executed, but the outcome unclear. The two-hour series finale also showed us Amanda being charged with sexual harassment in the workplace, and Alison realising, as she was about to walk down the aisle with Billy, that her long-running nightmares were actually memories of childhood sexual abuse by her father. (Melrose Place likes to pick up on current topics from the news – sexual harassment by women, Hollywood prostitution rings, repressed memories of incest – as long as they are about sex.)

In these final episodes, Melrose Place also acted as the host for a new series: just at it was launched by an association with the successful Beverly Hills 90210, so now it launched a new Spelling series – Models Inc, starring Linda Gray (Sue-Ellen of Dallas) who had appeared in four episodes of Melrose Place as Amanda’s mother. Its place in the Spelling pantheon, alongside Charlie’s Angels, 90210, Mod Squad, Dynasty, Fantasy Island and Starsky and Hutch, is assured.