Monica Pellizzari is a young and single-minded director of acute sensitivity and originality. She is representative of a new generation of filmmakers who come from different ethnic backgrounds but share an interest in articulating their emotional and cultural experiences in a multicultural society. These young inventive imagemakers seek to address issues of ethnic stereotyping, racism, marginality, cultural identity and displacement – in a word, cultural otherness. It is too early to characterize fully the more interesting visual and theoretical qualities of these new challenging movies. Nevertheless, what is evident at this stage is their collective wish to question conventional thinking about our post-war migration experience.

In the following interview Monica Pellizzari voices her dissatisfaction with the label of “ethnic” filmmaker. I think her complaint is justified – the adjective is too broad and lacks analytical precision. It is clearly indicative of the pressing need for a new critical language to interpret the works of such imaginative filmmakers as Monica Pellizzari, Franco di Chiera, Michael Karris, Lex Marinos, Teck Tan, George Karpathakis, Kate Pavlou, Luigi Acquisto and many others. Furthermore, what of some of the earlier figures who paved the road for these new directors? What do we know about the work of Giorgio Mangiamele and Ayten Kuyululu?

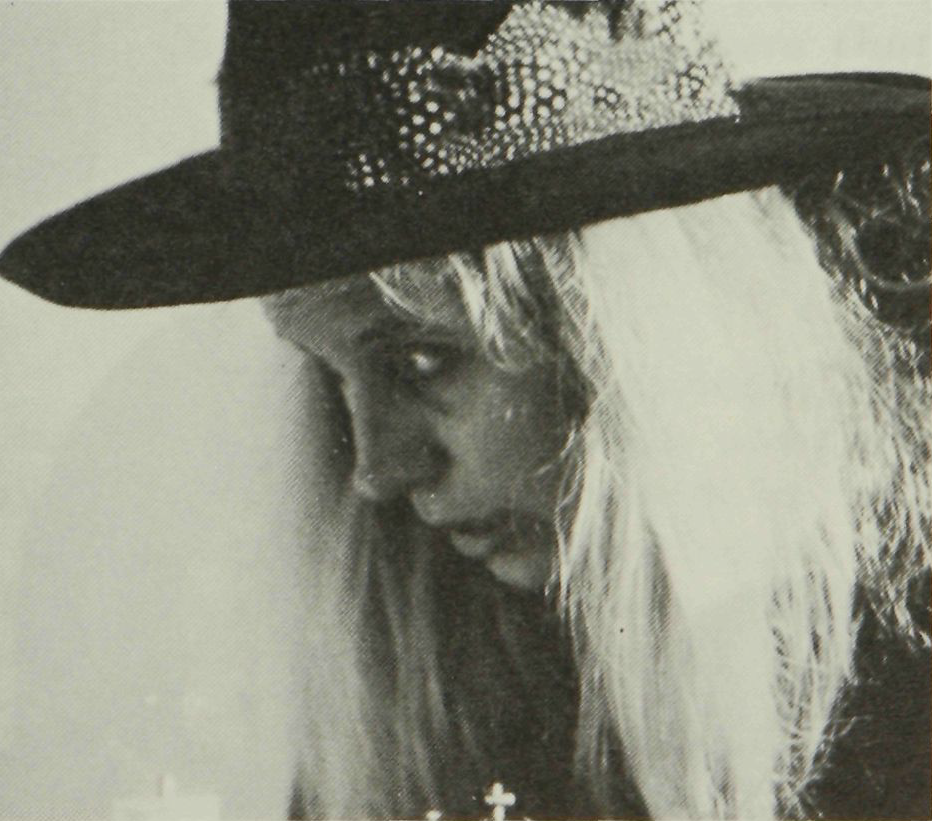

Let us return to Monica Pellizzari’s highly stimulating and intelligent work. What we see in Black Veil and Rabbit on the Moon, time and again, is her fluid ability to tell a story economically with maximum dramatic impact. In addition, her abundant stylistic capacity to portray her characters with almost Chekhovian empathy is clearly foregrounded in both of her movies. As a picturemaker, she is interested in changing our perceptions of other people. For the time being, she informs us, it is migrants that she wishes to deal with. She wishes to be both instructive and entertaining. On both matters her movies succeed. Raised in the western suburbs of Sydney as a post-war migrant’s daughter, she has a very intimate and comprehensive understanding of her working-class multicultural origins. It is this sensitive awareness of her past and present – what she has called her “first reality” – that she wishes to convey to us through the medium of cinema. One thing is certain: Monica Pellizzari is an explorer with an assured future as a filmmaker.

Both your movies Black Veil and Rabbit on the Moon are concerned with Italian characters living in urban Australian society. How important are multicultural themes to you as a filmmaker?

It has always been important for me to make films about my reality. I never knew it as specifically as the philosophy of multiculturalism or anything like that. It was just that Australia was made up of lots of different people from different parts of the world with different cultures and different experiences. So I endeavoured to make films that pertained to my own reality, hoping that other people from a similar reality could identify with it. And then “multiculturalism” happened around the same time, so I got slotted into being a “multicultural” filmmaker or making films that espoused the philosophy of multiculturalism. I am sure in five years, if the Liberal party gets in, it won’t be multiculturalism any more, it will be “one Australia”. Then you could try to talk about “one Australia” kinds of films.

Do you see yourself as belonging to a particular generation of ethnic filmmakers concerned with questions of ethnicity, displacement, racism, cross-cultural conflict, etc?

When I started out there were very few of us making films like my completed films. Before I went to the Film School I wrote things that I put to the Women’s Film Fund; they were rejected, mainly because I was not anybody then and I did not have the experience. That’s when I decided that I would apply for the school, go through it, come out the other end with some pieces of work to show around, and then I hoped to be in a position to get more money to make more films.

While I was at the school I was not labelled as a multicultural filmmaker. If anything, I was labelled as a wog filmmaker, which offended me. That was mainly by the Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Celtic staff who were at the school at that time and by my peers, very few of whom were making films like mine. I had only one predecessor, my friend Franco di Chiera, who made one of the first subtitled films in the country.

It was up to us filmmakers to gear the attitudes of the school and so along with the struggle to make the sorts of films with the content that I wanted, there was also the fight of trying to make films that required subtitles. So from a financial point of view I had to lobby very, very hard to get a unit set up; Franco had tried to do that but got knocked back very severely. The time was right, I suppose, when I came along. As a consequence, people after me have continued exploring their different ethnic backgrounds.

I really don’t like being called an ethnic filmmaker because that tends to slot you into places like SBS TV and SBS radio and that is it. Work there is rare, therefore that is something that bothers me. I’d love to go and direct Neighbours tomorrow and have people from all walks of life in an episode – that is the way it should be. I don’t think one should be a multicultural filmmaker or a wog filmmaker – I really detest the use of that word.

I think Rabbit on the Moon was successful for a few reasons: one was that it was unlike films of that kind (i.e. ethnic films or whatever you want to call them) in that there was a lot of humour infused into it.

At the moment I have been financed by the AFC to make my next short film – a half-hour drama. Again it looks at Italians but it does so in a very absurdist way, which lends itself to a lot of comedy. I think it’s based on characters and narrative more than it is based on the philosophy of multiculturalism.

How would you characterize the representation of non-Anglo-Australian migrants in Australian cinema today?

Well up to the last couple of years before we – that’s to say, people from specific ethnic backgrounds – started to make films about our own origins, our roots, the representation was usually by people that were not from that background. Or if people from that background were making films they did not have the skill or the tools or the know-how or the support. A lot of them were very talented but did not have the support to get aired or heard.

I think up to then we were seeing so many stereotypes that are still continuing but to a lesser degree. For example, in E Street we see an Italian character being played by an Irishman. It is pathetic. In Neighbours you see a Greek being played by a non-Greek person. The mainstream is so lazy about trying to tap into the communities to find the talent. I know that they have problems with time and restrictions but they could try a little bit harder; they could get more interesting representation on that screen.

In what thematic and visual ways does your work attempt to question stereotype images of migrants?

Firstly you are telling a story about characters and that is fundamental. There is a theme to your story – one or two themes, depending on the length of your film. And what I do is give a lot of attention to detail to these characters and the situation that they are in. They are reality.

The irony is that the problems I have are with Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Celtic characters. I just can’t make them round enough. I tend to put them in as mouth-pieces for something I’m trying to say. I’m trying to work on that because it is not my first reality, it’s my second reality, and that is the area that I have to keep working on.

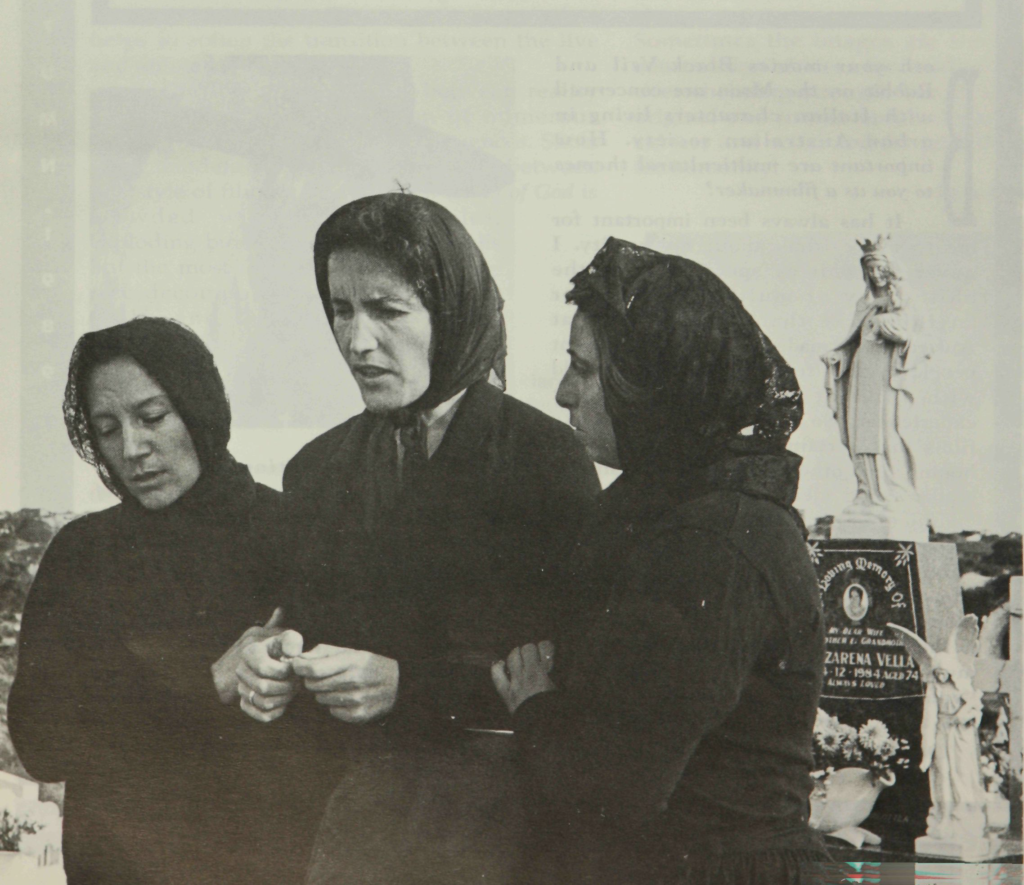

In Black Veil, the widow’s life is a very lonely one. She lives a marginal existence cut off from her country of birth and friends. Is this meant to be a metaphorical statement about post-war migrant experience in Australia?

Serafina, the character, is symbolic of post-war migrants in Australia. Primarily the problem is not being able to speak English. Also, women from non-English speaking backgrounds who live in Australia tend to be very isolated. Once their husbands or their families go they are even more isolated. They keep hold of those traditions that they grew up with.

Not only is Serafina, the widow, misunderstood and alienated but her “Good Samaritan” friend, the young Italian boy who rescues her from his Anglo-Saxon friends, seems to be misunderstood by his parents. You seem to be saying here that communication is extremely difficult to achieve whether it is across ethnic and cultural barriers or within one’s own ethnic situation?

The character of Angelo was actually based a lot on that boy, that actor. He was going through awful problems with his own identity, trying to work in Australia looking the way he looked, with his past, and also trying to relate to his family who were very deeply rooted in the traditions of Italy (particularly the region he came from). It was also about me – things that were happening to me at the time. So I say that character was a representation of Italian youth, be it male or female, who want to be Italian but don’t know which parts of being Italian are the good parts to hold onto and which parts are the negative parts. For me, I resolved a lot of that by going to Italy.

Ironically, after making that film the actor who played Angelo was so encouraged by the process that he went to Italy to discover his roots. Now he is very eager and very proud to be Italian and wants to work in these sorts of areas and projects but he is not finding these sorts of scripts.

Why do the widow’s friends at her husband’s grave attack her with a crucifix?

Originally when I made that film it was 24 minutes long and I subsequently cut it as I felt I had laboured the point. There was a scene between Angelo and the widow where they were walking down the streets and she explains (it is after the nightmare) the fact that now she’s been seen as a witch not only by the locals but by her friends who basically have dumped her because they don’t understand what she is going through. Basically, it’s got to do with the loss of the patriarch: the fact when your husband was alive you had contact with lots of friends, when the husband goes you lose contact with them.

How autobiographical in content is Rabbit on the Moon?

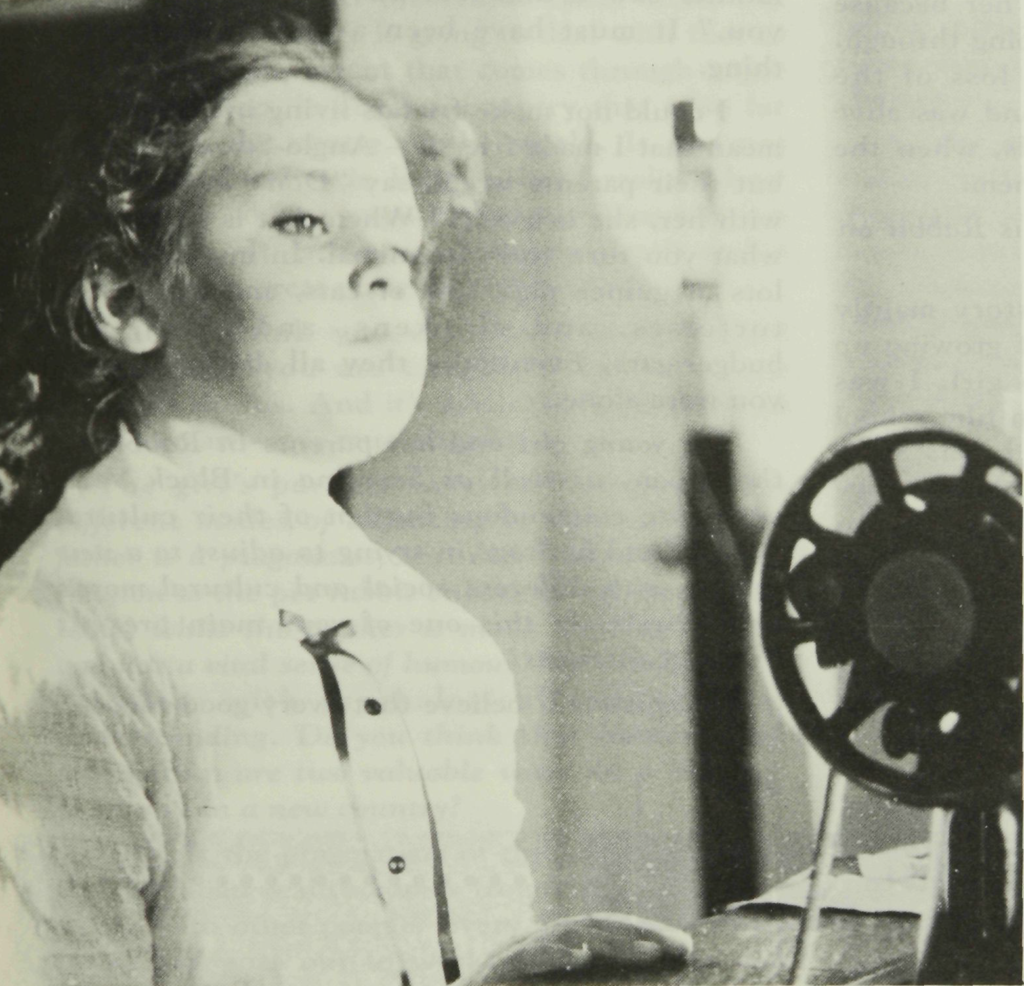

To begin with I had written a story mainly derived from my own experiences of growing up in Australia as a northern Italian girl. I was writing this when I was at the Italian film school in Italy. I needed a story line. I was very interested in myths as well. I heard the story about the rabbit on the moon, because in Australia a lot of people see a rabbit on the moon as opposed to a man on the moon or cheese on the moon or whatever. When I got back to Australia I started researching and I interviewed a lot of little kids from different migrant backgrounds aged between seven and 10 years old. They all had a pet – be it a chicken, a pigeon or a rabbit or whatever – that was edible and ended up being cooked through the father’s anger, through poverty or through tradition. Basically animals are a source of food and they are not seen as pets. That actually happened to me, although I did not know that until after I had made the film. My mother saw it and told me, “That happened to you.” It must have been a very subconscious thing.

I could not make friends living in Australia, I mean that I made friends – Anglo-Saxon friends – but their parents would say “Don’t hang around with her, she is a wog.” When that is said to you what you turn to is an animal. In my case I had lots of guinea pigs, lots of cats, and turtles and tortoises, and chickens, and birds, and budgerigars. Eventually they all died and again you were alone.

The young girl and her parents in Rabbit on the Moon, as well as Serafina in Black Veil, carry the tremendous burden of their cultural identity and heritage in trying to adjust to a new society with different social and cultural mores and rituals. Is this one of your main present thematic interests?

Definitely. I believe that every good film is a reflection of the filmmaker and that’s what I’m going through. I feel very displaced in this country and very alone. Even though I have people around me from my own background, they are either very traditionalist or they have completely dropped their links with their roots.

Again, my next film deals with displacement. Every character in the film is displaced, from the old man through to the child. After that, I’m sure, that the feature is going to deal with that as well. It is displacement that comes through anger and frustration, living in a country that is so far away from the centre of the world. It was not until I went to live in Europe that I realized how Australia is so far away. I often say Australia is a great place. It is a cross between death and a holiday. It’s a great place to have a holiday.

I don’t think you can live a truly happy existence if you are caught in between two different worlds. And it’s particularly hard if you are a woman – it is much harder.

The girl’s parents seem to represent two different modes of adjusting to Australia. The father is a pragmatist, a realist (particularly in relation to the pet rabbit ending up on the dinner table) while the mother is much more of a stoic and has a vital sense of humour. She provides her daughter with psychological comfort and understanding. Do you think that humour and pragmatism are two valuable ways for a migrant to survive in a new country?

I think the pragmatism of the father adjusting to Australian reality comes from the fact that he works with other people. Every day he leaves the house and goes out to work, as my father did. Therefore he mixes with people from different backgrounds (mainly Anglo-Saxon), and he tends to fit in a little better because he learns the language more rapidly than the mother. Sometimes we think, “These poor women isolated at home”, but sometimes I wonder which choice I’d rather have when I used to see my father come home and weep because of the fact he was treated badly, as a wog. But at the same time living within your own house can create your own little world, you know, you can only face the world when you go out to shop or whatever – doing the duties to survive. But at home you can harbour your dreams and your fantasies. I found that in my house a lot of humour came from my mother through her interpretation of Australia. In a way it’s quite sad when you stop and analyze it, but on a superficial level it’s hysterically funny.

Finally, are there any local and/or overseas directors who may have influenced you as a filmmaker?

When I was about 14 years old I saw Picnic at Hanging Rock and I just loved the film though everyone criticized it for not having a definitive ending. I just thought that there was such a sensitivity and beauty in that film that I just became obsessed with it. I became obsessed with the music, the images: I could not get enough of the film – the script, the book, you name it. My aim in life was to work with Peter Weir. Years later, I pursued that. I got to work with him. He’s probably my favourite being in the whole world. I really love his cinema, I love his way of telling stories. I love the mystery he imbues in his films and the sensitivity he portrays in his characters.

At the other extreme there is my link with Italian cinema. I saw a few Italian films. Living in Australia at the time it was very hard to get access to any Italian films. Then I started going to the cinema and I saw a few of Lina Wertmuller’s films. I just went “Wow – here is a woman not pulling punches” – political punches, and they >were done with humour and they were about women and about the North and the South (which I really identify with). Again it was my aim – to work with her. A few years later I got to do that and got to know her quite well. I must say that I think her recent films have lost that originality and punch, but I still maintain she has made some of the best films to have come out of world cinema. So I draw a lot from these two filmmakers. And of course, influences from Italian cinema, from Fellini to Rossellini. I think that they have made fantastic films and have a very interesting vision of the world.

Subconsciously, I am sure they have influenced me. However, I don’t go out of my way to emulate anybody. My films are a reflection of me and everything that affects me.