Tracey Moffatt’s seventeen-minute, 35mm film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990) catapulted the director onto the international stage. Born out of a distinct aesthetic vision and confidence as a marked departure from the documentary-realist representations of Aboriginality that had characterised Australian mainstream filmmaking up until its year of release, Moffatt’s film can be understood as a juncture between a host of traditions in Australian landscape painting, particularly that of Albert Namatjira, in Hollywood melodrama, and in avant-garde production and sound design and cinematic acts of telling ghost stories.

Tracey Moffatt

Moffatt is a singular figure in both Australian and international art scenes. She is a photographer, filmmaker, installation artist and music video director. She has always asserted that, from an early age, she was fascinated with ‘popular cinema and the mass-produced image’:[1]Gael Newton, ‘Tracey Moffatt: Something More Series’, in Anne Gray (ed.), Australian Art in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2002, available at <http://cs.nga.gov.au/Detail.cfm?IRN=148563>, accessed 12 November 2014.

Cinema outings were rare. The first film I saw in a cinema was Mary Poppins at age five. I remember the outing vividly. To this day I still believe Mary Poppins to be a cinematic masterpiece. Those 1960s big budget Disney technicolor works of art remain a yardstick on which I judge almost all films, and possibly all other art … I’m always hungry for an image. All over the world I find myself drawn to bookshops. Even in art museums I prefer to visit the bookshop first. I want to see the artwork in reproduction before I see the real thing on the wall. I can stand in a bookshop and easily scan an art magazine or book in five seconds flat – computer-like, taking in, discarding, or storing for later use, for later (so people tell me) ‘appropriation’.[2]Tracey Moffatt, quoted in ibid.

Moffatt studied visual communications at the Queensland College of Art in Brisbane, where she was exposed to an eccentric film education:

The good thing about the course, and we didn’t have fabulous visiting lecturers like the kids get at the [Griffith] Film School, was that they pushed an appreciation of film history. Ninety per cent of our time was spent watching films. It gave me a good grounding in film history, which has been very helpful. I’m glad I learnt filmmaking at an art school.[3]Tracey Moffat, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘Tracey Moffatt, Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Cinema Papers, no. 79, May 1990, p. 21.

After graduating in 1982 she moved to Sydney and worked on a documentary entitled Guniwaya Ngigu (a.k.a. We Fight, directed by Madeline McGrady) about a Commonwealth Games protest, and in 1985 worked as a stills photographer on the SBS production The Rainbow Serpent. At this time, Moffatt was also commencing her still photography work, participating alongside Mervyn Bishop, Brenda L Croft, Daryn Kemp, Ros Sultan and others in an exhibition at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery in Sydney. She was also exhibiting images such as The Movie Star: David Gulpilil on Bondi Beach, with the eponymous actor in ceremonial face paint and lurid board shorts, lounging on a bright yellow car bonnet, beside a boom box and holding a can of Foster’s Lager; and Some Lads, which reworks the mid-nineteenth-century scientific studio portraits into posed, assertive images of Aboriginal youth. The year 1989 saw the Something More exhibition commissioned by the Albury Regional Art Gallery. This exhibition, which led to her international reputation as a photographer, comprised a set of stills for a film about the trials of a poor but restless ‘coloured’ girl in rural Australia who wants ‘something more’ out of her life than her lot in the backblocks. In the opening shot, the would-be heroine wears an exotic Asian dress and later steals an old evening gown in her quest for a new identity. After various fragmented images of her encounters and adventures, the heroine’s ambitions to cross into the world of glamour and luxury are thwarted, and she dies on the road that promised escape from her origins.[4]Newton, op. cit.

From the outset, Night Cries’ sound and production design extends the concerns of Nice Coloured Girls, which sets in play a host of oppositions in realist literary, painterly and photographic representations of Aboriginal people.

At the same time that her still photography work was finding an audience, Moffatt was working on numerous video and documentary works. These include Watch Out (1987), a five-minute ‘discussion-starter’ dance video, part of the Women 88 series, that was funded by the Australian Bicentennial Authority; Spread the Word (1988), a nine-minute AIDS-awareness video commissioned by the Aboriginal Medical Service; and A Change of Face (1988), a three-part quasi-documentary about colonialist attitudes, captured through interviews with actors, directors and producers. Moodeitj Yorgas (1988), a twenty-two-minute video made for the Western Australian Women’s Advisory Council, features out-of-sync interviews with prominent Aboriginal women, whose voices are heard while the audience watches silent video portraits; these are linked using dramatic segments of women in black silhouette, each of whom enacts brief vignettes over stories told in two Aboriginal languages.[5]Catherine Summerhayes, ‘Moffatt, Tracey’, in Ian Aitken (ed.), The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, Routledge, London & New York, 2013, p. 643. The nine-minute It’s Up to You followed in 1989.

Moffatt’s photography and video work prior to her better-known Nice Coloured Girls (1987) and Night Cries exhibit the kind of metatextual and appropriative method of her later films. With larger budgets and more cinematic means at her disposal, Moffatt was able to realise fuller expressions of her concerns in these subsequent works.

Nice Coloured Girls

From the outset, Night Cries’ sound and production design extends the concerns of Nice Coloured Girls, which sets in play a host of oppositions in realist literary, painterly and photographic representations of Aboriginal people, including the ways in which race relations – a dialectic of white and black – have been conditioned by the white settlement of Australia. As such, Nice Coloured Girls acts as a precursor to Night Cries. In the former, four urban Aboriginal girls (Gayle Mabo, Cheryl Pitt, Janelle Court and Fiona George) spend the night out in Kings Cross to ‘roll’ a ‘captain’, an inebriated older white man (Lindsay McCorrmack), after he has bought drinks and dinner for them. This simple, concentrated, slight narrative provides the conceit for Moffatt to construct a stylised, intricate web of two voiceovers – one Irish (by Norbet Mulholland) and one English (Ralph Cotterill) – reading out the diaries of colonists Watkin Tench and William Bradley; commentary from the girls in the form of documentary-like intertitles; a series of framed nineteenth-century paintings, in front of which dramatic vignettes are played out and one of which is eventually smashed; a studio rendition of a bar; and inserts of an Aboriginal woman (Rosemary Meagher) on rocks at the beach. These elements are interwoven among a complicated sound design of bush and sea sounds, the hum of the street and bar, and snatches of conversation – all forming a dense visual and sonic filmic text.

Text

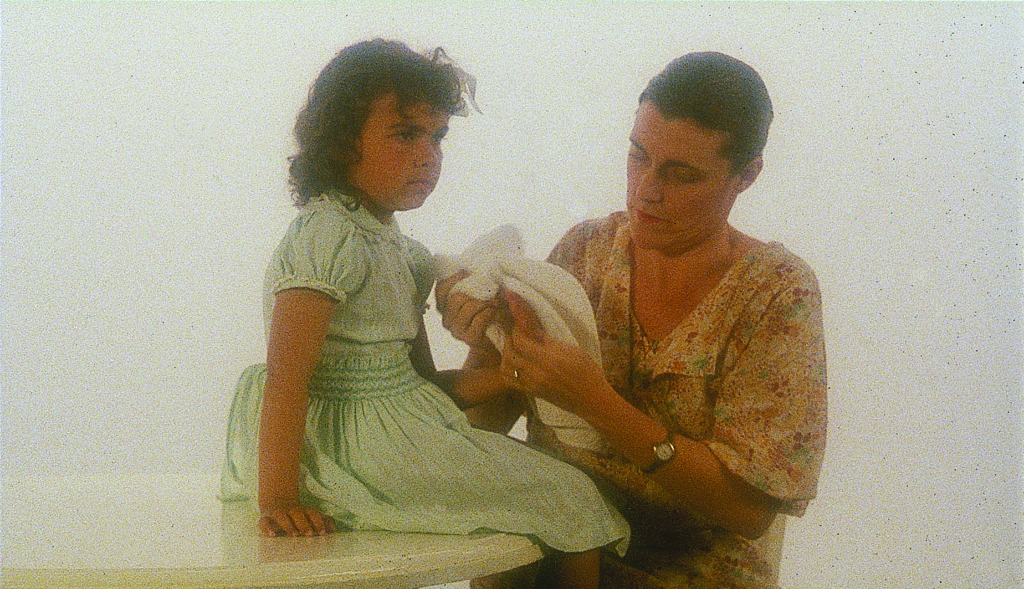

Night Cries is, at its heart, a story about an Aboriginal daughter (Marcia Langton) caring for her elderly white foster mother (Agnes Hardwick) in a remote rural homestead. But to focus solely on this relationship would be to diminish the complexity and, ultimately, the effect of the film. It contains largely stilled images with little or no character or camera movement. There are long sequences of black screen and blue-sky screen, flashbacks from various points of view, and interior ‘landscape’ shots devoid of characters. It is a noisy film crammed with sound effects, voices, screeches, and electronic, percussive and musical sounds. It features two musical performances by Jimmy Little, a popular country singer who was most prolific in the 1950s and 1960s. It is richly lit, with warm tones of red, yellow and brown, and an outback mountain landscape backdrop recalling the work of Albert Namatjira and the Aranda/Hermannsburg School of watercolour painting. It also includes sequences featuring younger versions of the mother (Elizabeth Gentle), the daughter (Alkira Fitzgerald) and the daughter’s playmates (Liam Wridgeway and Shaun Saunders) in grey-toned rear-projection seaside sequences.

Personnel

The film was written and directed by Moffatt, and produced by Penny McDonald, who has had a long career through her Chili Films production company. She has also worked with Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory; in the education sector, including the Australian Film Television and Radio School; for the New South Wales Film and Television Office; and for Film Australia. She is also currently the director of Screen Territory (formerly the Northern Territory Film Office), and was a founding member and past president of Women in Film and Television. Her producer credits include Too Many Captain Cooks (1989), which she also directed, My Mother My Son (Erica Glynn, 2000) and My Mother India (Safina Uberoi, 2001).

The 35mm cinematography in Night Cries was by John Whitteron, who worked on Rivka Hartman’s Bachelor Girl (1987), Kathryn Millard’s Point of Departure (1988), Chris Nash’s Philippines, My Philippines (1989) and, following Night Cries, Millard’s Light Years (1991), Daryl Dellora’s The Edge of the Possible (1998) and Trevor Graham’s Hula Girls (2005).

Art director Stephen Curtis is given much credit for the ‘look’ of Night Cries and went on to work with Moffatt on beDevil (1993), with Susan Murphy Dermody on Breathing Under Water (1993), and on Kate Woods’ Looking for Alibrandi (2000). Curtis, according to Moffatt, ‘is a theatre person, and what I like about his work is its staginess’;[6]Moffat, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 22. it is his stylised interiors that are immediately striking in Night Cries.

Moffatt also suggests other influences:

[Masaki] Kobayashi’s Kwaidan [1964], for example, was all shot in a sound stage. As for the shiny floor surfaces, they came from looking at Paul Schrader’s Mishima [subtitled A Life in Four Chapters, 1985], where excerpts of Mishima’s writing are illustrated by very staged studio set-ups. Schrader was influenced, I suspect, by Japanese theatre, Bhutto [sic], where they work a lot with reflections on stage. He didn’t go for realism at all, and I wanted to try and do the same thing. And if you are going to go artificial, go all the way.[7]ibid.

Night Cries’ soundscape effects were by Deborah Petrovitch, while drums and additional effects were by John Murphy; both are legendary figures in Australia’s post-punk noise and drone scene. Murphy describes Petrovitch as ‘like a cross between Jarboe and Diamanda Galas’[8]John Murphy, quoted in ‘Knifeladder – Organic Traces’, Compulsion Online, <http://www.compulsiononline.com/falbum7.htm>, accessed 12 November 2014. while, according to Moffatt, Petrovitch is

a video artist. She is also a sound artist who performs in pubs around Surry Hills at three o’clock in the morning, dressed in leather and crawling around a floor shaking a rattle. She’s really into voodoo and the sound at the beginning of my film that sounds like crazy monkeys is actually a woman choking. It was recorded in Haiti in the 1930s during a voodoo ceremony.[9]Moffat, quoted Murray, op. cit., p. 22.

‘It’s just the look of Jedda that I’ve copied … But as far as the landscape goes, I created my own. In part it is a reaction to a lot of Australian landscape film where there is an obsession with photographing real landscape.’

– Tracey Moffatt

Murphy likewise has a long history in experimental and noise music. He began working within Melbourne’s north-side ‘little bands’ scene – memorably fictionalised in Richard Lowenstein’s Dogs in Space (1986) – alongside people like Ollie Olsen and Marie Hoy from bands such as Whirlywirld, Hugo Klang, Orchestra of Skin and Bone, and No.

In all, Moffatt brought together an eclectic mix of cinema, theatre and experimental sound design as well as her cinephile knowledge to assist her in realising her singular vision for Night Cries.

Intertexts

As I have suggested, Night Cries is, in narrative terms, about an Aboriginal woman who looks after her elderly white mother in a rural homestead. For cinephiles, the film throws interpretive triggers, and commentators have seen Charles Chauvel’s Jedda (1955) as a precursor to the film in terms of its fragmented narrative style and the mise en scène. As Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper tell us, Jedda was the first feature made in colour by an Australian company and was conceived by Chauvel following the local success of his earlier film Sons of Matthew (1949):

he became determined to find another story that could be told in Australia by Australians. His usual backers, Universal, refused to support the project, believing it to be excessively offbeat, and Chauvel proceeded to form his own company and raise finance from businessmen in Sydney.[10]Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980, p. 220.

Jedda tells the story of a newly born Aboriginal girl adopted by a white woman, Sarah McMann (Betty Suttor), as a ‘replacement’ for her own child, who has just died. Sarah names the child Jedda, after a local bird, and raises her with European customs, disallowing her from making contact with the Aboriginal people who work on the station. After many years, the teenage Jedda (Ngarla Kunoth) finds herself drawn to Aboriginal people and myths while remaining tied to her white upbringing. When Marbuck (Robert Tudawali) appears at the station looking for work, his powerful build and Aboriginal machismo fascinate Jedda, who is initially attracted to him before he kidnaps her and takes her to his tribal lands. He is rejected by his tribe for breaking marriage law, and is cast out and also pursued by the men from Jedda’s station. Marbuck is driven insane and falls to his death, taking Jedda with him, off a cliff. Of course, the chase sequences across the landscapes of the Northern Territory include landmarks such as Standley Chasm and Ormiston Gorge – both near Alice Springs – and the area around Mary River in the far north of the state, close to Darwin.

Part nightmare, part paean to the spirit world, Night Cries crashes history and present into each other, drawing on the world of popular culture … to explore how race relations are impacted by and impact on familial relations.

Langton contends that Jedda ‘expresses all those ambiguous emotions, fears and false theories which revolve in Western thought around the spectre of the “primitive”’ and ‘rewrites Australian history so that the black rebel against white colonial rule is a rebel against the laws of his own society’.[11]Marcia Langton, ‘Well, I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993, available on the Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au:443/getmedia/580b7762-ceb4-4b3f-abad-7ec91b4e6adf/WellIHeard.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2014, p. 45. For Moffatt, Jedda was the starting point from which to distil her film:

I really like the set, which is a homestead interior. It is very American, very Bonanza, from the era. When Australian films were trying to be like American Westerns – even down to the landscape and music. So I decided to re-create the set in a film.

Then I took two of the film’s characters, Jedda, the black woman, and her white mother, and aged them as if thirty years had past [sic]. In the original film, Jedda is thrown off a cliff and killed. I wanted to resurrect her, and place the two of them back in the homestead situation, living out their lives.

But as I developed the script, the film became less about them and more about me and my white foster mother. I was raised by an older white woman and the script became quite a personal story. The little girl who appears in some of the flashback sequences looks a lot like me. That is quite intentional.[12]Moffat, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 22.

Moffatt then qualifies these narrative concerns:

It’s just the look of Jedda that I’ve copied, that sort of artificial interior. But as far as the landscape goes, I created my own. In part it is a reaction to a lot of Australian landscape film where there is an obsession with photographing real landscape. I’m not particularly obsessed with landscape, and I like to think I can create my artificial version of it.[13]ibid.

While Night Cries is Moffatt’s (re)imagining of Jedda, the film homes in on the ‘ambiguous emotions’ that Langton identifies, condensing and realising them aesthetically, and utilising sound and production design to set things in motion.

Night Cries is comparatively sparse, yet utilises the same strategy as Nice Coloured Girls. Extending the use of the studio in the former film, Night Cries is entirely studio-bound; alongside its brevity, this intensifies the film’s departure from the low-budget realism that abounds in Australian cinema. This intensification is evident in the gleaming red of the floor of the homestead, the warm red and yellow glow of the diffuse lighting, and the bright blue of the studio sky, as well as the howling wind, the shrieks and screams, and the grating and scratching of corrugated iron. Every wheel squeak, dingo yowl, lip smack, laboured exhale, train whistle, wheel thunder and door clunk is at the forefront of the sound mix.

Visually, the film’s mise en scène utilises a host of intertexts to construct an imaginary landscape. One of these intertexts operates through the use of a studio backdrop that is reminiscent of the work of Albert Namatjira.[14]The backdrop in Night Cries recalls Namatjira’s Ullambaura Haast Bluff (c. 1946) and Gosses Bluff Range (c. 1945). For many Australians, Namatjira’s work and those of the Aranda/Hermannsburg watercolour school are immediately familiar as embodying a landscape ‘type’ redolent of commerce, tourism, 1950s kitsch and an attendant oppressive suburban reverie. Laleen Jayamanne points to the ways in which Namatjira and the Aranda school were rejected by the art establishment despite their popularity, and how the school’s innovative use of watercolour challenged contemporary notions of modernity.[15]Laleen Jayamanne, ‘“Love Me Tender, Love Me True, Never Let Me Go …”: A Sri Lankan Reading of Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Framework, nos 38–39, 1992, p. 89. The school’s artworks were an example of the adaptation of Aboriginal ceremonial art practices into watercolour style, which was met with enthusiasm by commercial enterprises recognising the potential of the works for white audiences.[16]One of the first films of the fledgling Department of Information Film Unit was Namatjira the Painter (1947), directed by Lee Robinson and produced by Ralph Foster. In Night Cries, the Namatjira-like backdrop functions as a haunted screen, at once recalling these traditions in 1950s commercialised Aboriginal art and divested of all cultural specificity. As Ingrid Periz puts it:

Namatjira’s work serves as a backdrop, a screen denuded of the watercolour’s charm, functioning simply as a sign, not of nature but of another sign, hollowed out and empty. This is a landscape inhabited by memory – of a once great cattle station fallen victim to a changing agricultural economy, of foregone hope, of resentment and familial obligation.[17]Ingrid Periz, ‘Night Cries: Cries from the Heart’, Filmnews, vol. 20, no. 7, August 1990, p. 16.

After the title sequence replete with buzzing insect tones, a train chugging and screeching voices, Night Cries cuts to a black screen. For several seconds we hear the opening of the song ‘Royal Telephone’ before the film cuts to another 1950s figure: that of Aboriginal musician Jimmy Little. With his coiffed hair and sideburns, semi-formal suit and tie, and expressive hand gestures, Little’s crooner persona recalls an era of masculine performers such as Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Jim Reeves. Little performs without backing music, and his appearance and the song, along with the title sequence, are equally jarring and displacing, redolent of a nostalgia for the 1950s and 1960s as well as a middle-of-the-road sensibility. ‘Royal Telephone’, a version of a Burl Ives song, was a top-ten hit for Little; in 1964, a year after the song’s release, he was voted Australian Pop Star of the Year, and he continued to have success until the mid 1970s.

According to Jayamanne, Little’s function in Night Cries fits a schema of aesthetic assimilation. Following on from her assertions regarding the Namatjira-like backdrop, she posits that Little’s rendition of ‘Royal Telephone’ puts into play a sanitised pop-culture image of Aboriginality that precisely exemplifies an Indigenous reworking of international models of musical performance as well as Western Christianity.

[Little] mediates several cultural forces via his body/voice. With style and panache he embodies cultural assimilation. Here the notion of assimilation may suggest the mimicry involved in camouflage, the point of which is not to be able to tell if you are there or not. Now you are there, now you are not, it all depends on how you look. Ambivalent, unsettling perception becomes necessary: the performer is working in a tradition which is not his but which he sings as his own.[18]Jayamanne, op. cit., p. 92.

In Night Cries, Little’s figure interrupts as it prefigures the scenes featuring the mother and the daughter. In these ways, the performance of ‘Royal Telephone’ haunts the film, returning in various ways to condition the reading of the images interlaced with it.[19]Jayamanne tells us that ‘in a series of shots putting the guitar strap over his shoulder, adjusting it, then adjusting his collar in an effort to get comfortable so as to perform […] the sound here is that of static electricity. The song he then sings silently is “Love Me Tender, Love Me True, Never Let Me Go”.’ This song was first recorded by Elvis Presley, who was famous for appropriating black musical forms but is also a figure who has been invariably refashioned and appropriated well beyond his mortal death. The closing images of the film and the end credit sequence show Little miming the fully accompanied version of ‘Royal Telephone’. Here, Little returns again and again – from history and from within the film – to reconfigure himself and his era among the ruins of a popular-culture figure contemporaneous with him, Jedda.[20]Following Night Cries, Little returned to performing, garnering some success again. In 1999, in an echo of Rick Rubin’s revitalisation of Johnny Cash’s career, he released Messenger, an album of cover versions of songs by Paul Kelly, Nick Cave, Warumpi Band, The Go-Betweens, The Church and others.

These returnings and ellipses, caught among the flashbacks and interspersals, signify a ghostlike dreamscape. Part nightmare, part paean to the spirit world, Night Cries crashes history and present into each other, drawing on the world of popular culture, including Technicolor film, to explore how race relations are impacted by and impact on familial relations. In her follow-up film beDevil, Moffat makes explicit her interest in ghost stories while still employing the short-film form, this time in a trilogy comprising the segments ‘Mr Chuck’, ‘Choo Choo Choo Choo’ and ‘Lovin’ the Spin I’m in’. Largely studio-set, beDevil takes the intensity enabled by the short form – as seen in Nice Coloured Girls and Night Cries – and, across the trilogy, extends the rich colours and stylistics of her earlier films. Virginia Fraser describes the film thus:

beDevil is intensely Australian in ways both familiar and strange. The characters inhabit real and imagined north Queensland landscapes – mostly bizarre, hyperbolic, and artificial (created in a warehouse studio by production designer, Stephen Curtis, an army of carpenters and other set technicians) representing the heightened locations of memory, with semi actual, realistic locations from the televised present.[21]Virginia Fraser, ‘beDevilling’, Metro, no. 96, Summer 1993/94, p. 15.

Again, Moffatt confounds realist filmic practices while simultaneously inviting spectators to embrace new ways of reading and, therefore, new ways of seeing her Australia. As Carol Laseur tells us,

the stories are an ongoing interventionist practice into a destabilising of white Australian history as a master narrative. More than simply evoking a different (or ‘new’) set of voices, beDevil suggests the vital and ongoing processes of cultural definition and redefinition.[22]Carol Laseur, ‘beDevil: Colonial Images, Aboriginal Memories’, Span, issue 37, December 1993, p. 76.

Reception

Despite its distinction from most contemporary Australian cinema, Night Cries was warmly received overseas and in Australia, being selected in competition and nominated for the Palme D’Or – Best Short Film at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival. That same year, it won Best Australian Short Film at the Melbourne International Film Festival and Best Short Film at the Montreal Women’s Film Festival, and in 1991 attained the Special Jury Award at Finland’s Tampere International Short Film Festival.

Manohla Dargis, in New York’s The Village Voice, included Night Cries – alongside Jane Campion’s Sweetie (1989), Aki Kaurismäki’s The Match Factory Girl (1990) and Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger (1990) – in the paper’s ‘Our Favorites of 1990’, describing it as ‘a grand opera of silence and maternity, as opulent as Robert Wilson, as soulfully anguished as [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder’.[23]Manohla Dargis, ‘Our Favorites’, The Village Voice, 8 January 1991. The New York Times’ Caryn James compared Night Cries to Yvonne Rainer’s Privilege (1990), writing that ‘a fresher approach to the subject of women’s identity is taken in Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy [… which] manages to be formally innovative and thought-provoking at once’.[24]Caryn James, ‘Women on the Subject of Menopause’, The New York Times, 26 September 1990, <http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/26/movies/women-on-the-subject-of-menopause.html>, accessed 12 November 2014. Evan Williams wrote, in The Weekend Australian, that Night Cries

is a fascinating work, visually impressive, with a powerful, if not immediately accessible, message […] as I discovered on a second viewing, Night Cries yields much to the mind and eye as we contemplate its disturbing, sometimes frightening implications.[25]Evan Williams, ‘Visual Cries Better by Half’, The Weekend Australian, 3–4 November 1990.

Much of the buzz around the release of Night Cries was accompanied by the heralding of a new, distinct, assertive voice in Australian cinema. Moffatt’s work was seen as a marked departure from the then-contemporary Australian films – for example, Return Home (Ray Argall, 1990), The Big Steal (Nadia Tass, 1990) and Nirvana Street Murder (Aleksi Vellis, 1990) – that relied on a documentary-like realism. While Australian cinema turned to the city and the suburbs for images of identity, reacting to the decline of what Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka have termed the ‘Australian Film Commission genre’ – as seen in the landscape films of the 1970s and 1980s, such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975), My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979), The Getting of Wisdom (Bruce Beresford, 1978), The Devil’s Playground (Fred Schepisi, 1976) and The Mango Tree (Kevin Dobson, 1977)[26]Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, Anatomy of a National Cinema, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, pp. 33–4. – Moffatt returned to that much-mythologised landscape in order to rework and reconfigure its representations using her modern, Aboriginal, cinephilic and popular-culture sensibilities.

A filmmaker belonging to Moffatt’s intellectual and aesthetic lineage is Warwick Thornton, who as a director – with a number of short and feature films, photographic works, videos and installations – has further stretched the presumptions about Aboriginal filmmaking in this country. In his early shorts such as Payback (1996) and Mimi (2002), documentary shorts such as Willigan’s Fitzroy (2000) and The Old Man and the Inland Sea (2005), and the award-winning Nana (2007), Thornton marked out a space for himself as an original voice working across diverse forms including his cinematographic work on his and others’ projects. Samson & Delilah (2009) won him the Australian Film Institute’s awards for Best Director, Best Cinematography and Best Original Screenplay, and the film won the Caméra d’Or and competed in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. The film was also nominated as Australia’s official entry to the Academy Awards’ Best Foreign Language Film category. Like Moffatt’s Night Cries, Samson & Delilah has seen Thornton being recognised internationally, but it is his The Darkside (2013) that provides the most explicit connection to Moffatt. Following the lineage of cinematic tellings of Indigenous ghost stories set off by Night Cries and beDevil, The Darkside features prominent Indigenous and non-Indigenous actors such as Langton, Romaine Moreton, Deborah Mailman, Bryan Brown, Jack Charles, Claudia Karvan, Aaron Pedersen and Sacha Horler telling stories to-camera.[27]Alongside The Darkside, Thornton established The Otherside, a project allowing Indigenous ghost stories to be uploaded to an online archive and accessed on various media; see <http://www.theothersideproject.com/the-otherside/stories>, accessed 17 November 2014. His latest project, True Gods, is a contribution to the nine-part anthology film Words with Gods (2014), alongside international directing figures such as Guillermo Arriaga, Emir Kusturica, Héctor Babenco, Amos Gitai and Hideo Nakata.

Contemporary Australian Aboriginal cinema

In concluding, I would like to mention two intriguing frameworks by which Tracey Moffatt’s work has been understood: first, Aboriginal filmmaking, and second, in relation to a minor multicultural cinema in Australia. In ‘Aborigines, Film and Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy: An Outsider’s Perspective’, American E Ann Kaplan writes:

Like Nice Coloured Girls, Night Cries makes an important cultural intervention. Just as locating and celebrating Aboriginal racial specificity is one important current intervention, so also is starting the task of seeing cultural interrelatedness. Even as an outsider, one can appreciate (Moffatt’s works precisely help one appreciate) the difficulty of formulating desirable modes of cultural interrelatedness in Australia: as the first ‘Australians’, how do Aborigines want now (after all that has happened) to relate to later Anglo-Celt, European, and Asian immigrants?[28]E Ann Kaplan, ‘Aborigines, Film and Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy: An Outsider’s Perspective’, Bulletin of the Olive Pink Society, vol. 1, no. 2, 1989, p. 16.

And, in his Australian National Cinema, Tom O’Regan places Moffatt’s work alongside that of Pauline Chan, Monica Pellizzari and Clara Law as exemplars of multicultural cinema. As O’Regan argues, multicultural cinema (such as the works of Tracey Moffatt)

imagines its task as one of accentuating differences. It projects the expression of differences as an ethical principle. It projects itself on the side of the emergent and the open-ended. It imagines another beginning in the cinema and another chance for Australia.[29]Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 330.

This article has been refereed.

Bibliography

Manohla Dargis, ‘Our Favorites’, The Village Voice, 8 January 1991.

Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, Anatomy of a National Cinema, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988.

Virginia Fraser, ‘beDevilling’, Metro, no. 96, Summer 1993/94, pp. 15–8.

Caryn James, ‘Women on the Subject of Menopause’, The New York Times, 26 September 1990, <http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/26/movies/women-on-the-subject-of-menopause.html>, accessed 12 November 2014.

Laleen Jayamanne, ‘“Love Me Tender, Love Me True, Never Let Me Go …”: A Sri Lankan Reading of Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Framework, nos 38–39, 1992, pp. 87–94.

E Ann Kaplan, ‘Aborigines, Film and Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy: An Outsider’s Perspective’, Bulletin of the Olive Pink Society, vol. 1, no. 2, 1989, p. 16.

‘Knifeladder – Organic Traces’, Compulsion Online, <http://www.compulsiononline.com/falbum7.htm>, accessed 12 November 2014.

Marcia Langton, ‘Well, I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993, available on the Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au:443/getmedia/580b7762-ceb4-4b3f-abad-7ec91b4e6adf/WellIHeard.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2014.

Carol Laseur, ‘beDevil: Colonial Images, Aboriginal Memories’, Span, issue 37, December 1993, pp. 76–88.

Jimmy Little, Messenger, music album, 1999.

Scott Murray, ‘Tracey Moffatt, Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Cinema Papers, no. 79, May 1990, pp. 19–22.

Gael Newton, ‘Tracey Moffatt: Something More Series’, in Anne Gray (ed.), Australian Art in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2002, available at <http://cs.nga.gov.au/Detail.cfm?IRN=148563>, accessed 12 November 2014.

Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996.

Ingrid Periz, ‘Night Cries: Cries from the Heart’, Filmnews, vol. 20, no. 7, August 1990, p. 16.

Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980.

Catherine Summerhayes, ‘Moffatt, Tracey’, in Ian Aitken (ed.), The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, Routledge, London & New York, 2013, pp. 643–5.

Evan Williams, ‘Visual Cries Better by Half’, The Weekend Australian, 3–4 November 1990.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Director/Writer Tracey Moffatt Producer / Production Manager Penny McDonald Cinematographer John Whitteron Art Director Stephen Curtis Editor Phillippa Harvey Sound Recordists Liam Egan, Geoff Stitt Format 35mm Film stock Agfa-Gevaert Length 17 minutes

MAIN CAST

Daughter Marcia Langton Old Mother Agnes Hardwick Singer Jimmy Little Young Daughter Alkira Fitzgerald Young Mother Elizabeth Gentle

Endnotes

| 1 | Gael Newton, ‘Tracey Moffatt: Something More Series’, in Anne Gray (ed.), Australian Art in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2002, available at <http://cs.nga.gov.au/Detail.cfm?IRN=148563>, accessed 12 November 2014. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Tracey Moffatt, quoted in ibid. |

| 3 | Tracey Moffat, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘Tracey Moffatt, Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Cinema Papers, no. 79, May 1990, p. 21. |

| 4 | Newton, op. cit. |

| 5 | Catherine Summerhayes, ‘Moffatt, Tracey’, in Ian Aitken (ed.), The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, Routledge, London & New York, 2013, p. 643. |

| 6 | Moffat, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 22. |

| 7 | ibid. |

| 8 | John Murphy, quoted in ‘Knifeladder – Organic Traces’, Compulsion Online, <http://www.compulsiononline.com/falbum7.htm>, accessed 12 November 2014. |

| 9 | Moffat, quoted Murray, op. cit., p. 22. |

| 10 | Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980, p. 220. |

| 11 | Marcia Langton, ‘Well, I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993, available on the Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au:443/getmedia/580b7762-ceb4-4b3f-abad-7ec91b4e6adf/WellIHeard.pdf>, accessed 12 November 2014, p. 45. |

| 12 | Moffat, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 22. |

| 13 | ibid. |

| 14 | The backdrop in Night Cries recalls Namatjira’s Ullambaura Haast Bluff (c. 1946) and Gosses Bluff Range (c. 1945). |

| 15 | Laleen Jayamanne, ‘“Love Me Tender, Love Me True, Never Let Me Go …”: A Sri Lankan Reading of Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’, Framework, nos 38–39, 1992, p. 89. |

| 16 | One of the first films of the fledgling Department of Information Film Unit was Namatjira the Painter (1947), directed by Lee Robinson and produced by Ralph Foster. |

| 17 | Ingrid Periz, ‘Night Cries: Cries from the Heart’, Filmnews, vol. 20, no. 7, August 1990, p. 16. |

| 18 | Jayamanne, op. cit., p. 92. |

| 19 | Jayamanne tells us that ‘in a series of shots putting the guitar strap over his shoulder, adjusting it, then adjusting his collar in an effort to get comfortable so as to perform […] the sound here is that of static electricity. The song he then sings silently is “Love Me Tender, Love Me True, Never Let Me Go”.’ This song was first recorded by Elvis Presley, who was famous for appropriating black musical forms but is also a figure who has been invariably refashioned and appropriated well beyond his mortal death. |

| 20 | Following Night Cries, Little returned to performing, garnering some success again. In 1999, in an echo of Rick Rubin’s revitalisation of Johnny Cash’s career, he released Messenger, an album of cover versions of songs by Paul Kelly, Nick Cave, Warumpi Band, The Go-Betweens, The Church and others. |

| 21 | Virginia Fraser, ‘beDevilling’, Metro, no. 96, Summer 1993/94, p. 15. |

| 22 | Carol Laseur, ‘beDevil: Colonial Images, Aboriginal Memories’, Span, issue 37, December 1993, p. 76. |

| 23 | Manohla Dargis, ‘Our Favorites’, The Village Voice, 8 January 1991. |

| 24 | Caryn James, ‘Women on the Subject of Menopause’, The New York Times, 26 September 1990, <http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/26/movies/women-on-the-subject-of-menopause.html>, accessed 12 November 2014. |

| 25 | Evan Williams, ‘Visual Cries Better by Half’, The Weekend Australian, 3–4 November 1990. |

| 26 | Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, Anatomy of a National Cinema, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, pp. 33–4. |

| 27 | Alongside The Darkside, Thornton established The Otherside, a project allowing Indigenous ghost stories to be uploaded to an online archive and accessed on various media; see <http://www.theothersideproject.com/the-otherside/stories>, accessed 17 November 2014. |

| 28 | E Ann Kaplan, ‘Aborigines, Film and Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy: An Outsider’s Perspective’, Bulletin of the Olive Pink Society, vol. 1, no. 2, 1989, p. 16. |

| 29 | Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 330. |