‘With great power there must also come – great responsibility.’ This simple sentiment – made famous in its original form in a Spider-Man comic published in 1962,[1]‘With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility’, Quote/Counterquote, 5 July 2012, <http://www.quotecounterquote.com/2012/07/with-great-power-comes-great.html>, accessed 1 August 2016 then in Sam Raimi’s eponymous 2002 film – has become the moral cornerstone of what we know as the superhero genre. Once considered ‘kids stuff’ and confined to the pages of comic books, the genre has risen to become a multi-billion-dollar cultural form possessing legitimate artistic and social significance, and part of that enduring relevance can be attributed to how it plays out the fundamental truth that lies at the heart of the above phrase.

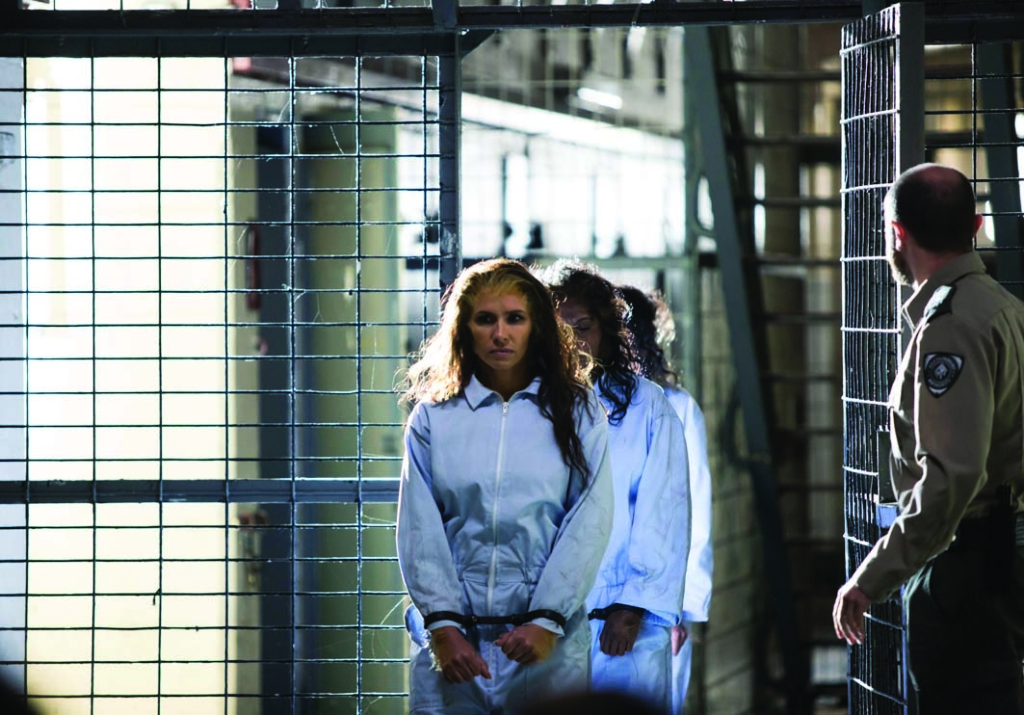

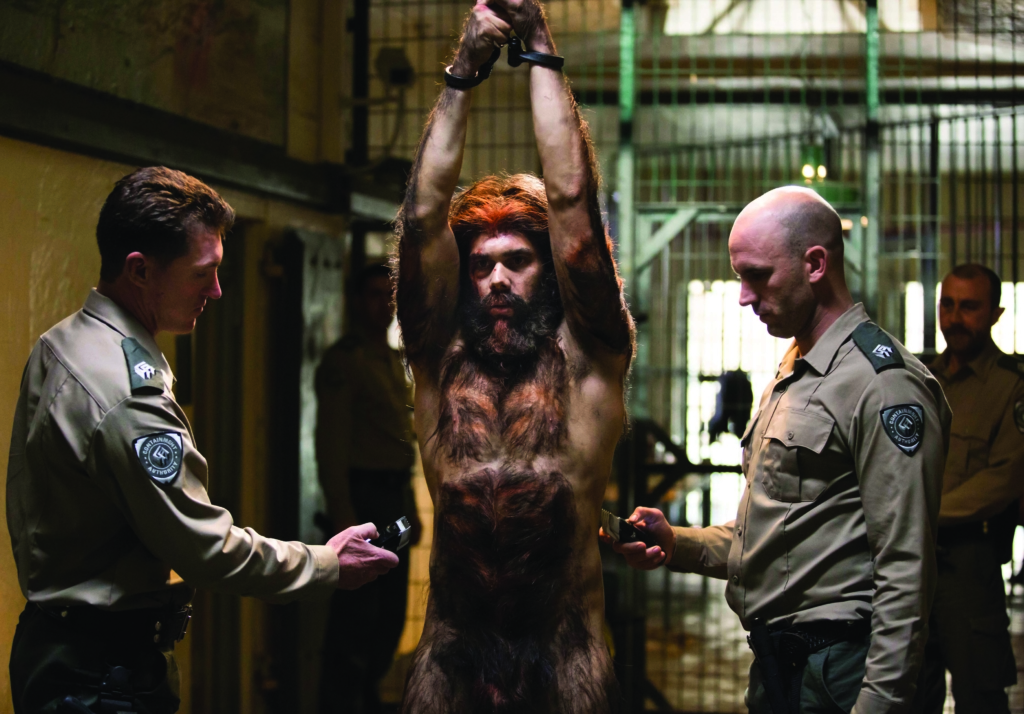

The ABC’s Cleverman has been promoted as Australia’s take on the genre. An ambitious co-production between Australia, New Zealand and the US, it represents an attempt to marry Australia’s tradition of pulp filmmaking – which has produced cult B movie classics like Undead (The Spierig Brothers, 2003) and Razorback (Russell Mulcahy, 1984), along with internationally successful pulp hits like The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014) and George Miller’s Mad Max series (1979–2015) – with a contemporary, issues-based approach. The show’s premise certainly possesses a scope rarely seen in Australian genre material. Its setting is a dystopian near-future where the Hairypeople – powerful, non-human creatures who have existed among us, hidden for millennia – have revealed themselves, and been confined to a refugee camp-cum-ghetto known as The Zone. Kept under the increasingly violent watch of the fascistic Containment Authority, the ‘Hairies’ and the Indigenous population of The Zone find strength in brotherhood. However, it is clear that the authorities will not tolerate their makeshift community much longer – and conflict is looming.

Into this volatile situation is dragged drop-out bar owner Koen (Hunter Page-Lochard), who is chosen to adopt the role of Cleverman: a kind of shaman figure that is important in many Aboriginal communities, tasked with embodying a link between the physical world and the otherworldly realm of the Dreaming. Unwilling to take the responsibility of this position, Koen ultimately finds himself entwined with the fate of the Hairies and his kin to the point where he is forced to reconcile himself with his new powers and the job with which they come. Watching everything from the side is media mogul Jarrod Slade (Iain Glen), who has found a way to distil the superhuman abilities of the Hairypeople into a serum for human use, and needs Koen to complete his research.

While a great deal of the hype around the show has quite rightly centred on its importance in featuring Indigenous actors and their cultures in a commercial genre drama, its other big selling point is how it has been positioned as Australia entering the superhero market.

Again, it’s an ambitious set-up, one that Cleverman sometimes strains to juggle over its six-episode run. So pleased were the ABC and AMC-owned co-producer SundanceTV with early reactions, however, that a second season was green-lit before the debut episode even broadcast[2]‘ABC & SundanceTV Commission Second Series of the Genre Drama – Cleverman’, media release, ABC, 2 June 2016, <https://tv.press.abc.net.au/abc–sundancetv-commission-second-series-of-the-genre-drama-cleverman>, accessed 1 August 2016. – a strong statement of confidence in a show as yet unproven in the market.

Certainly, Cleverman is brimming with ideas. Its fantastical elements are drawn from select Indigenous customs and mythologies – subject matter that rarely finds its way into popular culture, even that of Australia. As Mitch Knox points out in his review of the first episode: ‘In the space of 52 minutes, viewers were exposed to more aspects of Indigenous culture than most non-Indigenous Australians received during 12 years of schooling (and arguably beyond).’[3]Mitch Knox, ‘Why Cleverman Is One of Australia’s Most Important TV Shows’, TheMusic.com.au, 3 June 2016, <http://themusic.com.au/opinion/filmtv/2016/06/03/why-cleverman-is-one-of-australias-most-important-tv-shows/>, accessed 1 August 2016. But, while a great deal of the hype around the show has quite rightly centred on its importance in featuring Indigenous actors and their cultures in a commercial genre drama, its other big selling point is how it has been positioned as Australia entering the superhero market. Series creator Ryan Griffen has described the show as having been created specifically with the goal of giving his son an Indigenous Australian superhero to look up to:

We would read comics – I’d act out the characters’ voices – and we’d watch Batman, Ben 10 and the [Teenage Mutant Ninja] Turtles regularly. That was our time to bond.

The genesis of Cleverman came five years ago […] playing dress-ups with my son. We were playing Ninja Turtles, and in that moment I suddenly wished we had something cultural – something Aboriginal – that he could cling to with as much excitement as he did with this.[4]Ryan Griffen, ‘We Need More Aboriginal Superheroes, so I Created Cleverman for My Son’, NITV, 31 May 2016, <http://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2016/05/31/we-need-more-aboriginal-superheroes-so-i-created-cleverman-my-son>, accessed 1 August 2016.

Clearly, the show has gone through a plethora of conceptual changes since this point, as it’s hard to associate the gritty, sex- and violence-stuffed show that has eventuated with pizza-munching reptiles. However, Cleverman does stay true to many of the conventions of superhero narratives, particularly those of ‘origin stories’ – tropes that have created a loose but relatively consistent set of expectations for a nascent superhero. What can be asked, however, is whether the show actually needed to adhere to these formats, and whether the kind of story that was conceived and sold is necessarily what it has evolved into.

Koen is very much framed with traditional hero tropes in mind. Estranged from his family and community, he supplements his takings from the bar that he runs with his mate and business partner Blair (Ryan Corr) by smuggling Hairies out of The Zone. It’s the kind of grim work that demands a great deal of cynicism to make a success from, and we meet Koen as he hits a low point while taking a Hairy family’s money then promptly shopping them to the Containment Authority for a bonus reward. His amoral attitude is barely even dented when the authority shoots the family’s youngest daughter dead during the raid, showing how emotionally isolated he is from the Hairies and the humans with whom they share ties.

Cleverman’s take on the superhero puts integration very much before isolationism, with Waruu’s tendency to think he always knows what’s best for the community seemingly parodying the aloof self-righteousness of the traditional hero.

In fact, Koen has embraced the society outside The Zone – the ‘normal’ society – and has willingly adopted its antipathy towards his people, rejecting his heritage. This is similar to many superheroes who have had less-than-honourable beginnings. Iron Man, for example, essentially began as a high-class arms dealer, and a plethora of popular heroes, among them Wolverine, Spawn and Black Widow, spent time as killers-for-hire before evolving into their heroic selves. These past blemishes bestow upon them a sense of inner conflict, a marrow-deep guilt that gives added meaning to the lives they save and transforms their need for redemption into added fuel to the engine that drives their heroic acts.

While Koen buries his head in the sand, the consequences of his actions reverberate throughout the rest of the story as the shooting of the Hairy girl becomes a national scandal. This also results in the imprisonment and torture of her brother, Djukara (Tysan Towney), and father, Boondee (Tony Briggs), as well as the selling of her mother, Araluen (Tasma Walton), into sex slavery. This leads to some of the series’ most disturbing sequences, as Araluen’s dignity is slowly shattered and she becomes a sex toy to slimy immigration minister Geoff Matthews (Andrew McFarlane). Koen’s need to atone for his actions and the suffering they have caused becomes a crucial element in his eventual acceptance of the title of Cleverman. Ultimately, he must confront both the girl’s spirit and the hot-headed Djukara to redress the imbalance and earn the right to ascend to his predestined role.

One of the ways the series diverts from earlier superhero narratives is how Koen’s fate and the role of the Cleverman are intrinsically bound to the community. Traditionally, superheroes have operated in isolation from society at large, be they in cloistered groups like The Avengers or active self-exile like Batman. The classic narrative states that this is a necessity of who they are, since their abilities are generally misunderstood by the public and can attract unwelcome (generally villainous) attention to their loved ones. Part of that great responsibility that comes with great power lies in keeping oneself hidden so as not to disturb the peace within the community.

This trope may make sense for Western societies, which are highly individualistic in nature, but not for Indigenous Australians, whose systems of kinship regard all members of the society as being related to one another. What’s more, these kinship systems place a strong emphasis on universal responsibility, with many communities intricately structured in ways that determine who will care for the sick and old, or orphaned children, and who can marry whom.[5]See ‘Social Organisation’, in ‘Traditional Life’, aboriginalculture.com.au, <http://www.aboriginalculture.com.au/socialorganisation.shtml>, accessed 1 August 2016. Though Indigenous Australian societies are hugely diverse, consisting of numerous groups (or ‘skins’) that can vary wildly in custom or even language, they all share a strong sense of common living that ensures that the fate of any one member is the responsibility of all – and, certainly, most don’t need an individual vigilante to solve all their problems for them.

Appropriately, it is not the Cleverman’s role to right everybody’s wrongs; rather, he serves as a galvanising figure. To many Indigenous Australians, the Cleverman is an integral element of the community, not just in a spiritual sense but also as a source of wisdom whose guidance helps shape society at large.[6]See Tim Richards, ‘ABC TV’s Gripping Indigenous Superhero Series Cleverman to Premiere’, The Age, 29 May 2016, <http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/drama/m28cover2-20160524-gp2e90>, accessed 1 August 2016. It is this intimate involvement with the community from which Koen initially recoils, and with which he must come to terms so that he can fulfil his destiny and lead his people in the looming battle against the Containment Authority.

Conversely, it is this responsibility – and, more importantly, the prestige attendant with it – that attracts Koen’s ambitious half-brother, Waruu (Rob Collins). An active and prominent advocate for the rights of The Zone’s denizens, Waruu is loved and admired in the community, while the recalcitrant Koen is generally disliked. However, Waruu is quickly revealed as having no aversions to committing less-than-savoury acts – including adultery and murder – to maintain his status, and his desire for prestige makes him covet the role of the Cleverman. When outgoing Cleverman Uncle Jimmy (Jack Charles) instead anoints Koen as his replacement, Waruu takes it as an insult to his current reputation and a lifetime of ambition. Consequently, he plots to win the position for himself, even if it means removing Koen from the equation permanently.

The closest analogue to the Koen–Waruu dynamic in superhero fiction is probably the relationship between Marvel character Thor and his nemesis and adoptive brother, Loki. Since their childhood, Thor has been the favourite of their father, Odin, with Loki’s not-insignificant abilities generally going unappreciated. This compels the jealous Loki to villainy, forever driven to best his brother and secure the credit he has always been denied. Interestingly, Cleverman inverts this dynamic: it begins with Waruu as the one who is admired in the community, and Koen as the outcast, the ‘bad seed’ who is isolated and ignored.

However, the dynamic gradually switches as Koen is drawn slowly but surely back into the community at the behest of his newfound powers, and Waruu, into cosying up to the government and media while alienating those close to him. In time, Waruu brings upon himself a far worse isolation, stuck between two worlds and belonging to neither. This only further cements the impression that Cleverman’s take on the superhero puts integration very much before isolationism, with Waruu’s tendency to think he always knows what’s best for the community seemingly parodying the aloof self-righteousness of the traditional hero. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that the brothers’ surname, West, gives Waruu what sounds like a conventionally alliterative superhero name. It feels like an ironic nod towards both his sense of entitlement and his misguided belief in his own heroism.

Though the series ends with Waruu still ensconced within the community (though not exactly popular once his illegal acts come to light), the conflict between Koen and Waruu remains within the series’ dramatic core. Waruu, in most respects, aligns with the classic ‘nemesis’ template, an equal and binary opposite of the hero, and it would not be surprising to see Waruu’s fall continue in Season 2.

Ultimately, while Cleverman adopts the trappings of the superhero narrative, it is clear, by the end of the final episode, that Griffen and co. have a very different kind of hero in mind. After confronting Waruu and defeating the Namorrodor – a mysterious creature of the Dreaming whose role is kept vague but appears to play a ritualistic part in the changing of Clevermen (Jimmy allows it to kill him, and defeating it acts as Koen’s final test before he can ‘come of age’) – Koen finally wins the respect of the community and joins them at the battlements, ready for the imminent clash against the authority.

Frustratingly, the show then cuts to the credits – but the point is made. Koen is not a superhero in the traditional sense of the term, there to fight for truth and justice for all; he is a leader made for the needs of a small group far removed from regular society, in opposition to the regime that larger society operates under. This is the hero, not as boy scout or vigilante, but as potential insurrectionist. Even aside from its racial aspects, Cleverman is a bold take on the superhero that has arguably not been seen in popular culture since Neo (Keanu Reeves) in The Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy (1999–2003).

What kind of hero Koen will turn out to be is left unresolved. But, with the question of peaceful resistance versus violence running through the series as a point of contention, there is no reason to assume that he will always need to save the day with action-heavy pyrotechnics. Cleverman may involve superhuman powers and mystical intrigue, but its themes of identity, community and prejudice suggest a far more subtle approach to salvation than we have come to expect from the spandex crowd. One hopes that, if the series’ creators can focus on these aspects going forward, we can give the world not just some ‘me too’ Australian superhero, but a hero that represents the uniqueness and complexity of Australia’s Indigenous cultures and their focus on shared struggle over self-centric glory.

http://www.abc.net.au/tv/programs/cleverman/

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility’, Quote/Counterquote, 5 July 2012, <http://www.quotecounterquote.com/2012/07/with-great-power-comes-great.html>, accessed 1 August 2016 |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘ABC & SundanceTV Commission Second Series of the Genre Drama – Cleverman’, media release, ABC, 2 June 2016, <https://tv.press.abc.net.au/abc–sundancetv-commission-second-series-of-the-genre-drama-cleverman>, accessed 1 August 2016. |

| 3 | Mitch Knox, ‘Why Cleverman Is One of Australia’s Most Important TV Shows’, TheMusic.com.au, 3 June 2016, <http://themusic.com.au/opinion/filmtv/2016/06/03/why-cleverman-is-one-of-australias-most-important-tv-shows/>, accessed 1 August 2016. |

| 4 | Ryan Griffen, ‘We Need More Aboriginal Superheroes, so I Created Cleverman for My Son’, NITV, 31 May 2016, <http://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2016/05/31/we-need-more-aboriginal-superheroes-so-i-created-cleverman-my-son>, accessed 1 August 2016. |

| 5 | See ‘Social Organisation’, in ‘Traditional Life’, aboriginalculture.com.au, <http://www.aboriginalculture.com.au/socialorganisation.shtml>, accessed 1 August 2016. |

| 6 | See Tim Richards, ‘ABC TV’s Gripping Indigenous Superhero Series Cleverman to Premiere’, The Age, 29 May 2016, <http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/drama/m28cover2-20160524-gp2e90>, accessed 1 August 2016. |