On April 6, 1895, with Australia in the grip of Depression, the Bulletin published a short sketch of life in the backblocks of the Darling Downs. Starting the Selection was the first of dozens of stories published in the Bulletin under the name Steele Rudd. It was also the beginning of a cultural phenomenon which saw a polymorphous “Rudd family”, reshaped by the ideology and showmanship of successive artists and entrepreneurs, rapidly grow beyond the control of its author. In 1899, a judiciously edited and illustrated compilation of the stories was published by the Bulletin as On Our Selection! It proved immediately popular. Adaptations for stage, screen and radio followed and attracted record audiences over many decades. By 1940, the book itself had sold a quarter of a million copies. During 1979–80, a theatre revival of On Our Selection (coming at the height of the history-led Australian film revival) took over $3 million at the box office. Other than Ned Kelly, it is hard to think of an Australian icon as potent or as enduring as the Rudd family’s Dad and Dave.

Thus, 1995, which is both the centenary of Rudd’s first story and also the official Centenary of Film[1]Australia’s first public projection was actually 1896., seemed a propitious year in which to release a new screen version of Dad and Dave: On Our Selection. It has not been so. On Our Selection (George Whaley, 1995) did not become the smash hit of earlier screen versions (1920 and 1932), despite being both cinematically accomplished and entertaining. It has been a heartfelt project, nurtured by Whaley during an eight-year struggle to raise finance and complete the film. And while there are always variable and sometimes ineffable reasons for lack of box office success, the failure of the film to appeal to Australians in large numbers, I believe, signals how rapidly mainstream Australian identity has changed and how antithetical the film is to our new-look nationalism. These are factors which those involved in the film’s production and distribution appear not to have anticipated. After all, it was not so long ago that Crocodile Dundee (1986) parlayed a similar brand of Australiana into a financial bonanza.

Then again, perhaps the film’s distributor, Village Roadshow, did understand its urban audience when, over-riding the producer’s request, they threw On Our Selection on to the maximum number of screens for a short run instead of building it slowly. The whisper around the industry when this happened was the same as it has been for the last seventy-five years: “we wuz dumped!” Village Roadshow was accused of not wanting to waste their screens on a film which could only be a moderate earner when it had a full slate of American imports coming in. Generally speaking, when the distributor is also the exhibitor their cut of the box office can cover a minor investment in an Australian film. The losses are incurred by the major investor, i.e., the government’s Film Finance Corporation.

Be that as it may, while On Our Selection was big box office in country towns like Toowoomba[2]As of October, 1995, On Our Selection had taken $1.2 million at the box office, half of which has been generated from country districts where the film is going strong. (Private communication from Tony Buckley, 18/10/95), Australians in city centres did not respond well to display ads which appeared to cross an antipodean Oklahoma (1955) with Ma and Pa Kettle (1950). Nor did we resonate to slang lifted from the poster for the 1938 Dad and Dave Come to Town: “CRIPES! Just what this country needs … a bloody (1938: darn) good laugh!” Nor to the claim with which the text continues: “They’re rough, tough and romantic … but they’re all ours!” Not so. The Rudds may be as ingrained in Australia as an old toenail, but – like “cripes” and “bloody” – they’re really not current usage any more. But does this mean they’ve got to go?

The new On Our Selection, for all its chocolate-box visuals (only a wee bit like Oklahoma), reproduces Steele Rudd’s dry social satire as an Australian past of greater social and political complexity than we usually see on our screens. And it would be sad if, in our rush to get over the rainbow and out along the information superhighway, urban Australia comes to regard Dad and Dave (and perhaps even Paul Hogan and Ned Kelly along with them) as undesirable cultural baggage. To jettison this aspect of our history would be to travel very light indeed. One has only to look at the new roles assigned to Bill Hunter, former ocker hero of Newsfront (1978) in the successful Muriel’s Wedding (1994) and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) to realise the fruitfulness of asking new questions of old icons.

On Our Selection does ask new questions of our settler past and contains much that is contemporary, relevant and continuous. Perhaps, stylistically, it celebrates the folksy “Dad and Dave” tradition with insufficient ironic distance for modernist audiences and this is where the trouble lies. But, its double centenary provoked my curiosity about how the Australian cinema and the Dad and Dave phenomenon have interacted over the years. When I compared the 1995 film with older versions, I was fascinated by their differing projections of pioneering settlement. I found it intriguing also how their production circumstances in the silent and early sound eras resonate within today’s struggle for a national cinema. My reflections on all this were augmented by a wonderful new book from the Queensland University Press, In Search of Steele Rudd, by Richard Fotheringham, which examines the creation of the Steele Rudd persona and the Dad and Dave phenomenon through the life of their author, Arthur Hoey Davis. The book enriches our viewing of both present and past films and gives considerable insight into how Davis’s original stories evolved into successive screen versions. Queensland University Press has also published the sixth-draft screenplay of the 1995 film. Taken together, this material opens up a valuable case study in Australian culture and society as we trace On Our Selection through its various manifestations, beginning with the vision of its originator.

Steele Rudd

Steele Rudd was the pen name of Arthur Hoey Davis who was born, the eighth of thirteen children, in 1868 near Toowoomba, Queensland. According to Richard Fotheringham, Davis’s father had been a convict. So too, we should add, had been the father of Ned Kelly who summed it all up on the gallows, just fifteen years before the appearance of Davis’s first story, with “that sardonic Australian remark, ‘Such is Life'”.[3]This is Manning Clark’s term in his History of Australia, Vol. IV, Melbourne University Press, 1978, p. 336. Indeed, Davis’s own wry, gallows humour emerged out of that same back-breaking, heartbreaking struggle which nourished Kelly’s banditry: the attempt to wrest a living from a small, undercapitalised family farm on inhospitable land – a centuries-old peasant dream of independence shattering against Australian realities.

In 1875, the Davis family moved on to their selection at Emu Creek on Queensland’s Darling Downs. The parents, Fotheringham tells us, had lived in the west Downs during the last years of the war between Aborigines and Europeans, in the course of which Davis’s father was speared in the thigh. Those years too were times of bitter struggle between selectors and squatters over land. The selectors won the right to land; the squatters got the best of it. Davis attended school for five years, to the age of 12, and then, as was common amongst selector families, he went to work for wages. For four years he encountered rural Queensland at all levels, working on stations and eventually becoming a stockman. The 1880s provided years of severe drought and physical hardship for the future novelist’s observation. Like his father, Davis was associated politically with the anti-squatter faction although he avoided dealing directly in his stories with the struggle in this arena to concentrate on the pioneer’s elemental struggle with inhospitable nature. (Aborigines were even less of an element in Rudd society.) At the age of 16, under pressure from his mother and through family political connections, Davis was provided with a position in the public service in Brisbane. There he survived the great economic depression of the 1890s in a job which gave him time for his writing.

On Our Selection‘s director, George Whaley, has suggested that the myth of Terra Nullius Mark I – there were no people in Australia until the Europeans arrived – has been superseded by the myth of Terra Nullius Mark II – there were no Australians in Australia until the multi-cultural present. But, of course, political and cultural nationalism made a coherent and conscious appearance over a hundred years ago, during Arthur Davis’s youth in the 1880s.[4]Stephen Alomes in A Nation at Last (Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1988) traces the forms, fluctuations and contradictions of Australian nationalism. Its flagship was the Bulletin, in whose pages writers like Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson challenged the Anglophile values which had largely dominated Australian cultural life. Predominantly city-dwellers, as Davis himself soon became, the Bulletin‘s artists and writers were part of a masculinist Bohemian intelligentsia which glorified the Australian bush, and found in it their own radicalism, male comradeship – the great Australian mateship – and belief in freedom from conventional restraints. The character of the itinerant bushworker embodied the essence of Australia; he represented an escape from urban, industrial civilisation which was, by definition, European. The bush was the “real” Australia and humorous realism its authentic Australian voice.[5]This concept of the Real Australia lives on today through ABC radio’s ‘Australia All Over – Macca on a Sunday Morning’.

Australian nationalism in this period is generally exemplified by the work of writers like Paterson and Lawson. Fotheringham argues that the Steele Rudd stories have been a hundred times more popular than Lawson’s. Yet Davis’s notion of Australian identity, while sharing some aspects of the Bulletin’s nationalist ideal, is not so palatable. To begin with, Davis was uninterested in mateship or masculine class solidarity. The male relationships which he describes are those of the patriarchal domination of the Rudd family by the authoritarian Dad. In reading the stories recently, I was struck by the thread of antagonism, rivalry and even cruelty which underlies the humour of his family relationships. No one escapes Davis’s ironic vision intact. There is no masculine hero to embody Australian identity: no man from Snowy River thundering iambically into legend. On the contrary, the Rudd community is composed of distinctly characterised families and individuals of different northern European origin. This identity is closer to historical actuality, and is reproduced also in the mix of Scottish, Irish and Scandinavian characters of George Whaley’s film, which additionally attempts a more realistic representation of women. Davis’s women are drawn as utterly saintly or wonderfully ridiculous.

While later popularisations of Dad and Dave travelled far from the realities of life on the Downs into broad farce and melodrama, Davis’s own characters are treated with a humour that is particular and well-observed. It is also a deeply pessimistic humour and, as Fotheringham demonstrates, trades on a repeated cycle of struggle and defeat by forces over which its characters have no control. For all their resilience, the Rudds exhibit that “typical” Australian passivity, that lack of drive which has been so remarked upon in studies of the heroes of our ’70s film renaissance. The Rudd boys – with the exception of Dan – are the eternal slaves of tyrannical Dad and although Davis skirts around the sickness and death that were so much a part of his own world, life is a perpetual struggle against unpredictable and uncontrollable drought, fire, flood, market prices, and human authority.

In the later stories, acceding perhaps to the popularity of his characters, Davis does indicate that the Rudd family has made a go of farming. However, this is not the tenor of the early stories. Where the 1920 and 1932 films celebrate free settlement as a way out of wage slavery, Davis’s original stories – like the Whaley film – are ambivalent. His personal experience hardly supported a Utopian vision of Australia as a nation of yeomen farmers taming an alien land. This ideological and social safety valve has persisted virtually into the present era, but, in actual fact, the Selection Scheme was always an Impossible Dream. Even in Davis’s day, there was ample evidence that escaping to the Australian bush and starting from scratch was, generally speaking, rarely an economically viable proposition.

A Royal Commission of 1883 has left a detailed analysis of the failure of the Selection Scheme as Davis knew it. It found that only about one-sixtieth of the 29 million acres selected over the previous 22 years was cropped. Of the 130,000 selections only about half had ever been settled as homesteads as required by law, and by 1883 this number had fallen to less than 18,000.[6]Greenwood, Gordon (Ed); Australia, A Social and Political History, Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1955, p. 118. In fact, Australia had a greater percentage of its population in towns than any other country of the period: 66% in 1891.[7]McQueen, Humphrey, A New Britannia, Penguin, Melbourne 1970. Clearly, the reality despite the dream was that the overwhelming majority of the population knew better than to actually turn farmer. Those who did were more often than not defeated by drought, flood, fire, poor soil, crop diseases, lack of capital, and the ruinous costs of labour and transport. By 1883 most of the survivors had acquired enough additional land to become graziers, if even in a small way. And, typically, as in Arthur Davis’s family, father and children periodically left the farm to work for wages on larger properties. In the stories, Dad might be “up the country earning a few pounds” and the rebellious son, Dan, is often away. Dan’s departure becomes a major point in the 1995 film which also has daughter Kate in the squatter’s employ as a maid. The 1920 and 1932 films adhere more closely to the myth and less closely to Davis’s stories, confining the family to a self-reliant and more isolated struggle with nature.

The Changing Face of Dad and Dave

It was the Bulletin itself which began the transformation of Davis’s original sketches of unnamed homesteaders into a tale of the Rudd family. Fotheringham describes how Bulletin editor A. G. Stephens drew the stories together into the 1899 book and, “in a moment of myth-making and marketing genius”, gave the family the same surname as the supposed author, turning documentary realism into pseudo-autobiography. Like others who followed, Stephens selected, edited and re-arranged Davis’s episodic stories into a more coherent and marketable narrative. Perhaps Stephens’ most far-reaching intervention was the commissioning of the book’s illustrations from half-a-dozen artists, deliberately emphasising the farcical rather than the realistic elements of the stories. There was little attempt by individual artists to standardise their portrayal of the characters, but Lionel Lindsay’s illustration of Dad and Norman Lindsay’s of Dave soon took on a life of their own with their animation on the stage by Bert Bailey and Fred MacDonald.

The flip side of Australian pessimism is our wild enthusiasm for the myth of success – the self-made man who starts from nothing and just might defeat the odds and win through. This was the vision created by Bert Bailey: Dad, the battler who never says die. In 1912 Bert Bailey, himself a self-made and successful entrepreneur, dramatised, produced and starred as Dad in a play of On Our Selection, and in 1932 likewise produced the Cinesound film adaptation. With Fred MacDonald as the lanky, bumbling Dave, the two dominated both of these popular productions, relegating the other characters to minor roles. For almost twenty years the play toured Australia and New Zealand, and “Dad and Dave” grew to almost mythological stature. Bailey’s reworkings of the original material can be seen in the play’s aggressive belief in self-help. The play also introduces a melodramatic plot, typical of the theatre of that period, involving murder and a villainous squatter, Carey. The cycle of defeat in Davis’s stories is here replaced by more thrilling stuff. When Dad beats Carey to a valuable piece of land, Carey impounds Dad’s cattle for money owing, and Dad brings down the curtain on Act One with a stirring speech of defiance. A version of this speech became a high point in the 1932 film.

Carey: I’m going to take possession of every head of stock on the place … I’ll break your spirit, Rudd.

Dad: (Sitting at a table, brooding) For years I’ve fought the droughts and the floods of this country. Two successive seasons the wheat failed and then when it had grown higher than the fence, a late frost withered and blackened it all up in the night … You want to break up the old home, the place where me sons and daughters were born. Well, take me few ’ead of cattle, take every stick in the place. But if you think you can break me spirit (striking the table with his fist) by the Lord, no! It’s the spirit of the pioneers who struggled to make the land.

Carey: Talk! Talk! Fine words no doubt, but what do they all amount to? The drought has got your crops, I’ve got your stock. What can you do now?

Dad: Wot the men of this country with health, strength and determination are always doin’. I can start again.

It’s worth a comparison with the original. Here is the end of a story in which Carey does Dad out of a piece of land:

Morning again. Dad halted at the foot of the Lands office steps and stared in surprise. Old Carey was feeling his way down them with a stick. Carey saw Dad and grinned. Dad went into the office and came out breathing heavily. He went down the street and searched for Carey till he missed the train.

“How’s it y’ didn’t get it?” Dave said in an unhappy kind of voice. Dad gave no reason. He sat down and thought, and we all stood round waiting as if something was going to happen.

“They’ve got it all right,” Dad groaned at last.

Then Dave’s opportunity came. “Yairs,” he said, “an’ they’ve got all our cattle – pounded every one o’ them, an’ ten shillings a head damages on them!”

Sarah rushed out, so did Bill and Barty; but Dave and Joe held Dad down and saved the furniture.

Further Transformations

Richard Fotheringham writes of the “savage feeding frenzy” which took place over the stories and characters which Arthur Hoey Davis – and A.G. Stephens – had created. As the “Dad and Dave” phenomenon took shape following the play and the 1920 Raymond Longford film, and with an oral tradition of Dad and Dave jokes already in existence, cartoons of a Dad-like figure – Bert Bailey style – began to appear in Smith’s Weekly. Dad was soon joined by Dave and, later, Mum and daughter Sarah. In the aftermath of the First World War, Smith’s Weekly had taken the Bulletin‘s nationalism to a reactionary extreme. It was racist, strongly anti-Communist and a passionate supporter of the soldier-settlement scheme and farmer-hero. Its Dad and Dave-like cartoon characters soon began to cross over into advertising, initially for farm machinery. Eventually both Bert Bailey and Fred MacDonald cashed in on the trend in person. In the ’30s, a photograph of the ubiquitous MacDonald was used to sell “Heenzo Cough Syrup.”[8]Smith’s Weekly, 7 September, 1935, p. 14. By then MacDonald was Dave, not only via the stage but on screen as well. His film character spanned a period of 23 years from the time of the “Hayseeds” comedies produced by Beaumont Smith,[9]The Hayseeds’ Back-Blocks Show (1917), The Hayseeds Come to Sydney (1917), The Hayseeds’ Melbourne Cup (1918), Prehistoric Hayseeds (1923 – MacDonald was unavailable) and The Hayseeds (1938 – with Tai Ordell who played Dave in 1920. MacDonald was appearing in the Cinesound films.) which began in 1917 (in which the Dave character is called “Jim”), to Cinesound’s final Dad and Dave film of 1940, Dad Rudd, MP.

In 1937 the first episode of Dad and Dave from Snake Gully was broadcast on Sydney 2UW. The program originated, in the words of Fotheringham, “out of a mixture of inspiration, opportunism, and marketing rat cunning.” Sponsored by Wrigley chewing gum through the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, the serial associated what was regarded as a dirty American habit with the most identifiably Australian characters available. Its theme music was “The Road to Gundagai”. The broadcasts continued for 30 years and were occasionally replayed on country and specialist radio until quite recently.

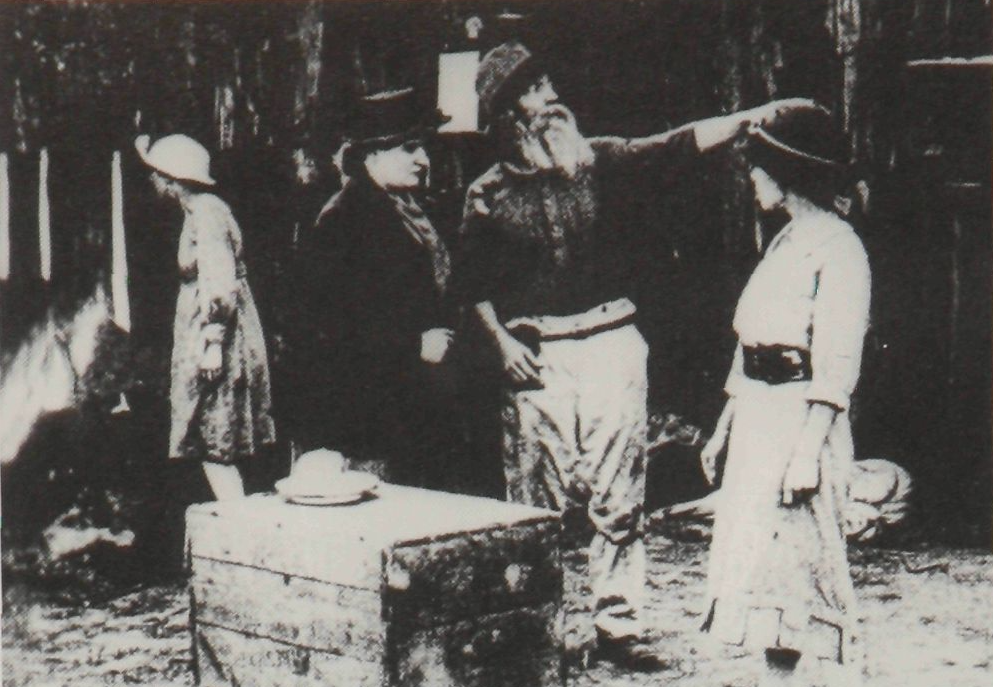

On Our Selection, 1920

Given the broad farce and crass commercialism of much of the reworking of Davis’s stories, the first film of On Our Selection, released in 1920, is all the more impressive for going in the other direction. Closer in tone to Steele Rudd’s stories, the film was “picturised and directed” by Raymond Longford, following his success the previous year with The Sentimental Bloke. Longford repudiated the artificial plot devices and buffoonery of the existing Bert Bailey play and Hayseeds films. It was reported that he “has the true Australian’s love for his country, and consequently objects strongly to seeing the characters which are presented to the public as natural types, turned into ridicule.” Nor did he like seeing the humour with which bush people face their many difficulties converted into “clumsy clowning of the ‘slapstick’ variety”.[10]Picture Show, 1 April, 1920, p. 44. His own celebration of the pioneer family was constructed with subtlety, poetic realism and humour based on well-observed characterisations. The film moves through loosely linked episodes of the Rudd family’s departure for the selection where Dad and Dave have built a slab and bark hut, the planting and harvesting of their first crop, and the interruption of the progress of the farm by drought and fire. During these hard times a romance develops between daughter Kate and neighbour Sandy Taylor, and more comic romances between Dave and Lily and daughter Sarah and Billy Bearup. The film ends happily with Kate and Sandy’s wedding and Dad’s acquisition of the deed to the selection.

On Our Selection was shot as the troops were still returning from World War I, following a period of considerable division in Australia with two conscription referendums and industrial action culminating in the 1917 “General Strike”. It was a period of increasing urbanisation and suburbanisation with 38% of the population now concentrated in the capital cities alone. Yet, as John Tulloch points out in Legends on the Screen, this was a period in which Australian silent films like On Our Selection idealised bush life at the expense of significant historical realities, including existing class hostilities. On Our Selection was an active proponent of the Impossible Dream as Longford saw it: “a sense of humour … courage and the capacity for work enabled our early settlers to overcome their many difficulties”.[11]This was suggested as Longford’s view of things, ibid. As Longford’s film was released, 35,000 grants were being taken up under the post-war Soldier Settlement scheme. By 1927 a third of these settlers had – once again – walked off their land.

Tulloch has drawn a connection between the legends of the bush pioneer and those of the Australian cinema pioneer. “The cinema elite,” he says, meaning the distributor/exhibitors, “used the Australian producers in the same way that the earlier entrepreneurial elite used the selectors: to continue the myth of a ‘magnificent reward’ through pioneering struggle, individual initiative and perseverance long after it was possible.”[12]Tulloch, John, Legends on the Screen: the narrative film in Australia 1919–1929, Currency Press, Sydney 1981, p. 356. It is a myth which today a director like George Whaley and his producer, film historian Tony Buckley, are constantly wrestling with. It is interesting that class antagonisms have been fully restored to their film’s settler society. Raymond Longford however, one of Australia’s truly gifted directors, railed against the cinema elite but appears never to have renounced the dream. Professionally, and perhaps personally, he could not find a way through this dilemma and, with the coming of sound, was frozen out of production.

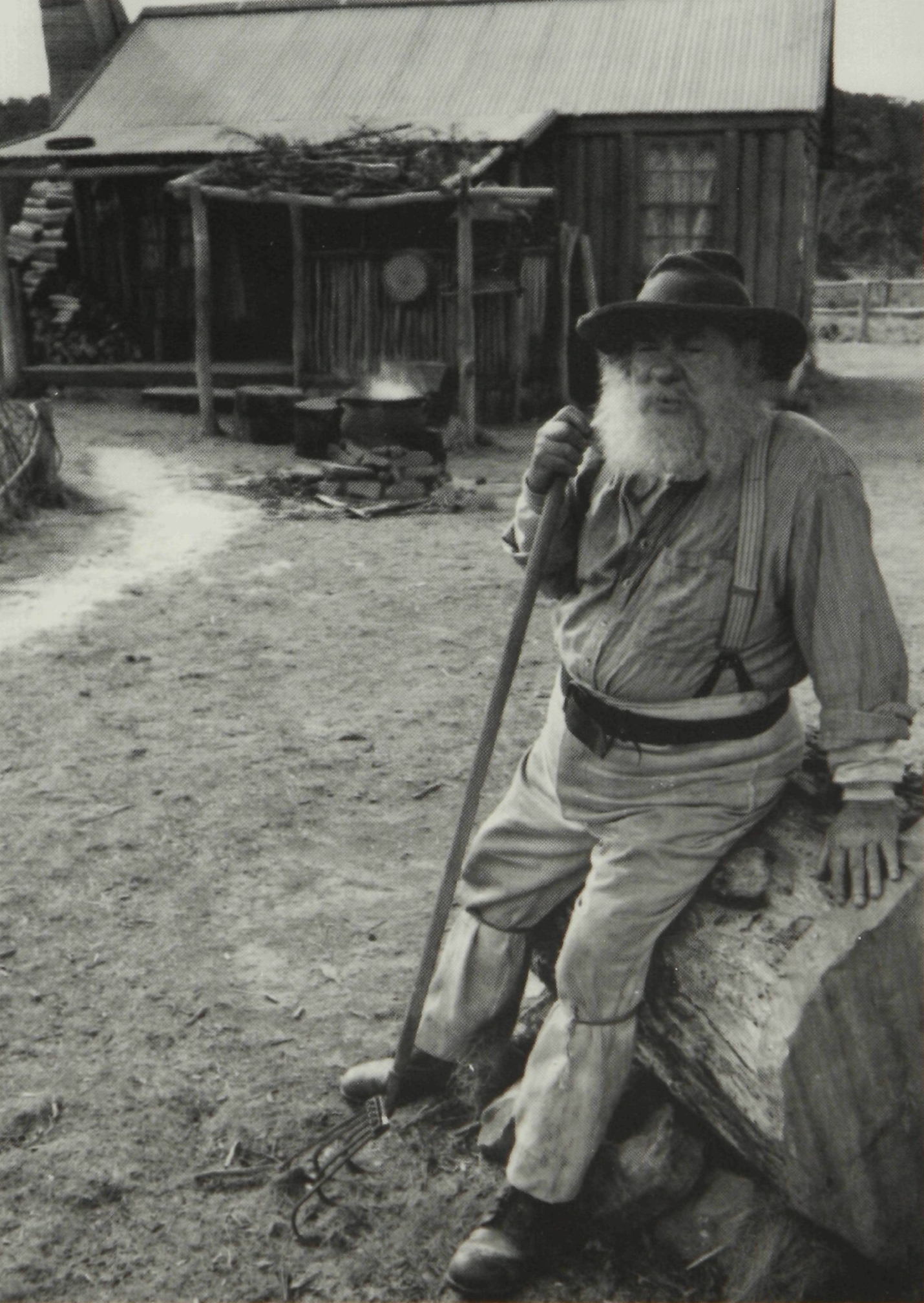

Raymond Longford was born in 1878. He made approximately thirty-five films, his first in 1911.[13]It is difficult to be precise because of the absence of adequate documentation. It is generally thought to be 35, including two films produced in New Zealand. Only five survive; two in incomplete versions, including On Our Selection. Longford was an early adherent of a growing international trend towards film realism and he achieved exquisite naturalistic performances. While some of his actors, like Percy Walshe, the ferocious, wiry Dad of the film, were experienced stage performers, others were found in the streets through a search for suitable “types”. Cranky Jack (who appeared in the lost footage) was a “well known identity” of the Sydney Waterfront and the youngest son, Joe, was a corner newspaper boy. In a period in which cinema and stage drama were still dominated by melodrama, Longford’s ideas of realism were connected to his nationalism. He believed that the best acting was not to act at all.[14]This view appears to have been the prevailing one internationally as directors worked to overcome the theatricality of earlier silent films. Imported Hollywood director Wilfred Lucas speaking at the opening of Snowy Baker’s Oxford Street acting school advised intending screen actors, ‘Learn not to act’, Picture Show, October 4, 1919, p. 23. Longford:

I’m making an Australian picture and I want the people in it to be real Australians. Now your average Australian is the most casual person under the sun, so if I put the players through their parts over and over again, worrying them, striving to perfect them, they might do good work, but they wouldn’t look like Australian … My way is to let them know the action I want, and allow them to go right ahead with it. For a picture like On Our Selection, in which it is absolutely necessary that the characters look natural, I think that’s the best course.[15]Picture Show, 1 April, 1920, p. 32.

When Longford made On Our Selection, he was at his artistic peak. Nevertheless, it was impossible for him to maintain continuity of production in Australia. At the 1927 Royal Commission into the Moving Picture Industry, he gave passionate testimony about the effects on his career of “the Combine”, a merger of key Australian distribution, exhibition and production companies in 1913 which soon became antagonistic to local production. The Combine’s control over exhibition outlets, as today, was used to facilitate the screening of imported films. In 1920 the imports numbered around 700 as opposed to ten Australian pictures produced, not all of which were successful and four of which were directed by Americans. Despite record box-offices for many of his films, including On Our Selection, Longford’s pioneering struggle and individual initiative did not result in a “magnificent reward”. When Longford formed his own production company with his partner and star Lottie Lyell in 1922, it was not successful and upon Lyell’s premature death in 1925, Longford went to work at Australasian Films for his old enemy, the Combine. At Australasian Films he was unable to repeat his previous successes. After 1926 Longford tried to get films to direct, but was shut out everywhere until 1934 when he made his only talkie. It was not well received although moderately profitable. During this period, he was sporadically employed as an actor or associate director on minor productions. In his later years he worked on the Sydney waterfront, so far forgotten that he was presumed dead when The Sentimental Bloke received its first screening in 20 years at the 1955 Sydney Film Festival. Longford was not invited. He died in 1959.

The fact that Longford represents the pinnacle of accomplishment in the silent era – a sort of antipodean Griffith with cameraman Arthur Higgins as his Billy Bitzer – says much about the opportunities provided by the Australian cinema. Perhaps it was Longford’s frustration which led him to claim, in retrospect, that he had used the close-up before D. W. Griffith. In fact, the comparison between the two directors is painful. Griffith started using close-ups in 1909–1910, as part of an innovative array of narrative devices. Between 1908 and 1913, the sophisticated Griffith had made 150 short films, constantly experimenting. In 1913 Griffith made a 4 reeler, and The Birth of a Nation, released in 1915 initiated his great epics – upwards of 12 reels long and drawing upon vast resources of crew, cast and technical equipment. Because Australia was the first country to produce feature-length films, Longford began his career with 4–5 reelers and the surviving version of On Our Selection is almost 7 reels long. But, typically for Australian films of the times, it was a cheap and simple production, probably made with a crew of 3 to 4 people.

In shooting On Our Selection, cameraman Arthur Higgins had no assistant and he achieved beautiful, poetic images on the slow, blue-sensitive, orthochromatic stock with no more lighting than a couple of reflectors. Interiors in the hut were shot with a gauze roof to diffuse the sun. In those days, cinematographers had no light meters, no standard ratings for film speed, and employed rack-and-tank processing whereby the negative was dipped in the developer until judged to be done. Tinted films were provided for the printing: blue for night, yellow for day, red for fire, as we see in the print of the film restored by the National Film and Sound Archive (using modern Aeroplane Jelly food dye to approximate the old colours). Arthur Higgins, one of three cameramen brothers, was just twenty when he shot his first film for Longford in 1911 and not yet thirty when he photographed On Our Selection. He was a tiny man, very much respected by his colleagues, and worked almost to his death in 1963.

The box office success of On Our Selection led to a 1921 sequel, Rudd’s New Selection, now lost, which was received even more favourably. Contemporary reviews of On Our Selection were mixed, as some critics were disturbed by its realism. Today, this distinctively Australian film stands up well to the test of time, even alongside other acclaimed overseas productions of the 1919-1922 period: F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1921), Fritz Lang’s Doctor Mabuse the Gambler (1922), Douglas Fairbanks’ The Mark of Zorro (1920), Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) and Orphans of the Storm (1921), Buster Keaton’s shorts, Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives (1921) and Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1921). The silent Australian cinema, in an era in which film required little capital to produce, is touted by some scholars as our “Golden Age”, but it is worth remembering the realities which confronted our filmmakers’ nationalist aspirations. Within the American studio system, John Ford directed 14 features released in 1919, four in 1920, and seven in 1921; Longford released one a year – when he was lucky. In Australia, continuous studio-based production always seemed to be just around the corner.

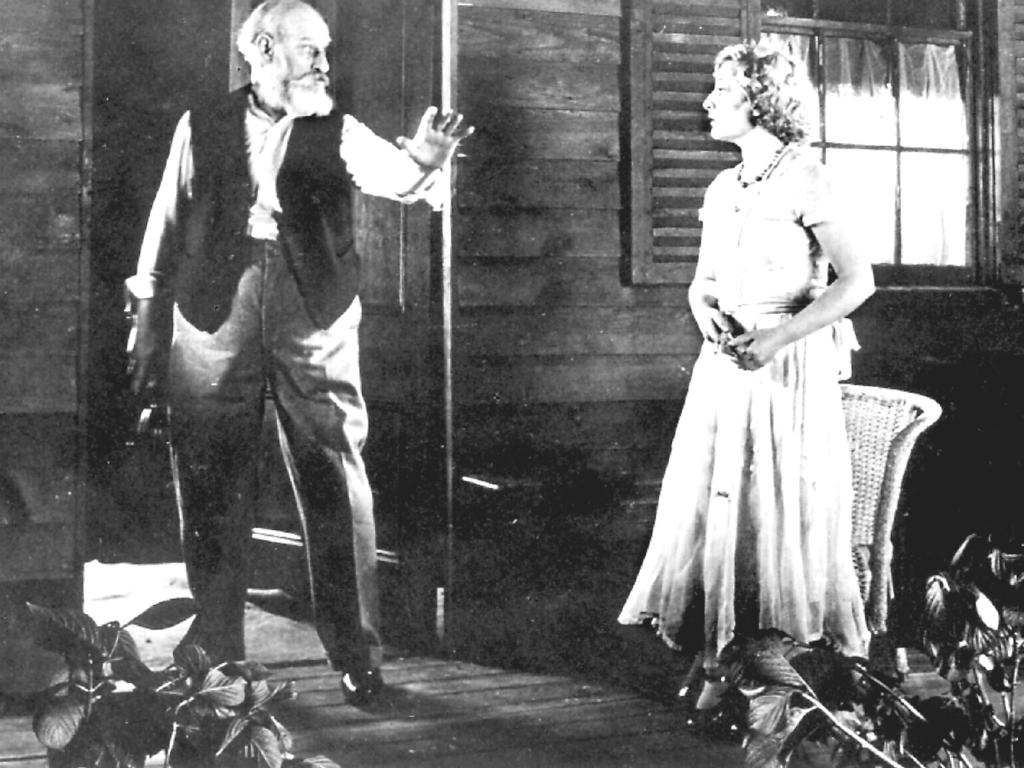

On Our Selection, 1932

The second On Our Selection was of a very different order to the first and did begin Australia’s one sustained and, within its own terms, successful attempt at continuous studio production. It was the first of 17 feature films produced by Cinesound before the cessation of feature production for World War II. One of three Australian films released in 1932, On Our Selection was dominated by Bert Bailey as producer, scriptwriter and star, with Fred MacDonald repeating his stage role of Dave. Ken G. Hall, at this time relatively inexperienced in production, was the director. The film was financed by Greater Union, the very Combine which Longford blamed for stifling Australian production. Hall had begun working for the Combine in 1917 at the age of 16, where he soon became a protege of Managing Director Stuart F. Doyle. After managing the Lyceum Theatre, Hall rose to the position of national publicity director of Union Theatres and Australasian Films (as it was then). A trip to Hollywood impressed upon him the necessity for creative people to watch the trends and calculate for future markets. As he wrote later:

Filmmaking is indeed a tough way of life and no quarter can be expected or will be given by the customer … the general public. There is no way you can get around, over or under that judgement.[16]Hall, Ken G., Australian Film: The Inside Story, Sydney, 1980, p. 27.

It was with this precept foremost in his mind that the former publicist turned to directing, well aware that despite the advantages of working from within Greater Union, only profits could ensure future production. Hall recalls that Doyle instructed him explicitly:

“Never make a failure”. What he meant by that was, if you make a failure, you’ll lose your support. As Ray Longford did. You lose your backers … It sounded pretty callous, but it was good advice. It made me make films of the kind that I would not have made of choice sometimes … I couldn’t afford to make a failure. Cinesound would have died on its feet … [17]Hall, Ken G. interviewed by Graham Shirley, 2/8/76.

In fact, On Our Selection was Doyle’s choice, not Hall’s:

I didn’t want to make a dirty-filthy “Dad ‘n Dave”. You know, everybody looked down their noses at “Dad and Dave”… They said, “Oh, surely you can do something better than that. Oh, surely.”[18]ibid.

The general public, however, was not “everybody”. Doyle, calculating on the continued popularity of “Dad and Dave”, believed correctly that the film would provide much-needed revenue for Union Theatres now, in 1931, badly affected by the Depression. The revival of this rural melodrama at a time when 47% of the population lived in the capital cities proved to be a big hit. The film basically follows the play with the inclusion of a murder mystery and considerable clumsy clowning of the slapstick variety. Dad is a battler, politicians get a serve, the rich – Carey and his womanising son – are foiled by the Rudds, the rain comes and all live happily ever after. Ken Hall worked with Bert Bailey to adapt the script for Depression audiences. The confrontation between Dad and Carey was rewritten to reflect the Rudd family’s poverty as well as their struggle with nature:

Dad: For years I’ve faced and fought the fires, the floods and the droughts of this country. I came here and I cut a hole in the bush when I hadn’t enough money to buy a billy can with, or a shirt to put on me back. I worked hard and honest, living on dry bread, harrowing me bit of wheat in with the brambles. But I never lost heart for one single moment. The cattle had perished and died before me very eyes, but … me spirit was never broken.

Perhaps these sentiments were designed to give hope at a time when, according to the calculations of the Economic News of the day, 38% of the 1931 workforce was unemployed![19]Economic News, 9 June 1932, p. 67 quoted in Wendy Lowenstein’s Weevils in the Flour, Melbourne 1978. Calculated on reported and unreported figures for each state. New South Wales was hit the hardest. In his Australian Film: The Inside Story, Ken Hall speaks of the Depression as “grim, bitter, hungry years” when he too felt the fear of losing his job and accepted a 50% cut in salary. Hall’s Labor sympathies were well known in later years. Yet, in the interests of commercial success, On Our Selection was deliberately aimed at distraction. Hall did not believe in “bringing politics into film”. As he once said in criticism of the overtly political stance of ’50s director Cecil Holmes, ” … the public don’t want to know. They want to know if you’re going to entertain them.”[20]Ken Hall interviewed by Bruce Molloy, 1 June, 1977. Hall felt that the key to success lay in showmanship: shaping and selling a film properly for the general public. And while a later generation of filmmakers criticised him for too great a reliance on “Hollywood formulas”, it should be noted that only one of his films failed to turn a profit.

Sounds of Australia

On Our Selection was made on a shoestring budget of £6000, with a crew of twelve. Its production values are not high; it played for melodrama and “hick” humour and most scenes retain the staginess of the original play. Nevertheless, it was the first Australian talkie to be shot substantially on location and its emphasis on the sounds of the Australian bush was a big selling point. Stuart Doyle’s announcement of the film’s impending production traded upon the popular appeal of an optimistic bush nationalism and, as with the bush films of the ’20s, held out the myth of a magnificent reward:

Opportunity will be taken to get really atmospheric Australian scenes and sounds into On Our Selection. The aim is to make it as thoroughly characteristic of our native land, and the bush will be presented not as a forbidding, gloomy land of droughts and semi-starvation, but as it really is – a great rich country which, like all others, passes periodically through trying times. We propose to show the outside world – and city born Australians themselves, for that matter – what the bush really is. The addition of sound gives the opportunity of capturing the very spirit of the back country, and of the sturdy pioneers who turned the wilderness into productive farm-lands.[21]Everyone’s, 11 March, 1931.

At a time when millions of dollars were being spent in Hollywood by RCA and Western Electric to perfect film sound, a Tasmanian radio engineer named Arthur Smith arrived in Sydney with £100 in his pocket. He teamed up with Bert Cross, head of Greater Union’s Australasian Film Laboratory, who, keen to bring his studio into the sound era, donated facilities for Smith to design and manufacture an Australian sound-on-film recorder. Smith and Cross experimented for a year and enlisted Ken Hall’s support. Doyle was sceptical and Hall didn’t blame him. He writes that prior to World War II, there was:

… an underlying lack of belief in Australian initiative, creativity, skills … In the twenties we were very much a sort of appendage of Britain, heavily dependent on her and other nations to supply our manufactured needs. We grew the wool and the crops and exported them. They came back to us ready to wear and to eat. Stuart Doyle’s doubt … about the capacity of any Australian to compete in a highly technical field with the giants overseas was not unreasonable.[22]Hall, op. cit.

Nevertheless, Arthur Smith did come up with an excellent sound system and, moreover – only the night before On Our Selection was to go on location – he and Cross finally arrived at a solution to the problem of portable power, enabling them to shoot sound without the support of mains electricity. Smith and Cross sound systems were subsequently installed in Australian cinemas. Thus, it is Smith, more than anyone else connected with the saga of On Our Selection, who best fulfils the role of Australian hero, the “Man From Snowy River”. His story of making do and winning through despite slender resources is one which is repeated in the achievements of many of our industry’s film technicians through the decades.

The publicity for On Our Selection was intensely nationalistic. For the first time ever, Australians would hear as well as see their own country. The cumbersome nature of the heavy equipment – sound and camera – imposed severe limitations on shooting style, but exteriors were shot primarily along the Nepean River near Castlereagh. Taking full advantage of this location, the film opens with a “Bushland Symphony” consisting of bush views and amplified bird calls. Audiences went wild. Typically, they greeted the opening with cheers. By 1933 On Our Selection had netted a return of over £46,000. By 1950 it had established a national box office record for any picture, domestic or foreign, released in Australia up until that time. It was still getting revivals in country cinemas twenty years later.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 August 1932, in praise of the film’s “vitality, originality and beauty”, declared: “the film can stand comparison with the finest products of Hollywood or Elstree.” Given how crude the film seems today, such a statement attests to Australians’ intense desire to see Australian images on the screen. Artistically, On Our Selection does not begin to compare with the finest films released around the world in the early ’30s. These include, for example, Jean Renoir’s Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), Rene Clair’s A Nous la Liberté (1931), Luis Bunuel’s L’Age d’Or (1930) and Land without Bread (1932), Fritz Lang’s M (1931), Ernst Lubitsch’s The Man I Killed (1931) and Trouble In Paradise (1932), Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934), George Cukor’s David Copperfield (1934), Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935), William Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931), Joseph Von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932), Mervyn LeRoy/Busby Berkeley’s Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Rouben Mamoulian’s Queen Christina (1933) and Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932). On Our Selection comprised half of that year’s local production in a period when in Hollywood John Ford alone was directing two to three films a year out of his total oeuvre of approximately 140.

Given the success of the film, Ken Hall should have attained a very magnificent reward indeed. He directed commercially successful features until World War II and headed the Cinesound Review newsreel into the mid-fifties. However, following the War, 50% of the shares in Greater Union, now managed by Sir Norman B. Rydge, were purchased by the British Rank Organisation and support for Australian film production was not resumed. Ken Hall, saddened and angry, bowed to the inevitable. He left Cinesound to run TCN-9 during its first ten years, retiring in 1966. Hall died in 1994 at the age of 93. A couple of years before his death, I introduced my young daughter to him at an open-air screening of his last Cinesound feature, Dad Rudd MP. The film had been received enthusiastically by a nostalgic audience which overflowed the Opera House steps. I hoped that some day my daughter would remember how she met a man who gave Australians an image of themselves at a time when virtually no one else succeeded in doing so. But she didn’t seem to care. Nor did she care later when, despite her resistance to Village Roadshow’s promotional material for the 1995 On Our Selection, I dragged her with me to a preview. She enjoyed the film, but it really meant little to her. Like most moviegoers under the age of 30 – i.e., the majority of post-television era cinema audiences – my daughter takes for granted the existence of Australian films while her heroes and narrative formulas emanate from Hollywood.

On Our Selection has received four nominations in this year’s Australian Film Institute Awards, but critics have not been as enthusiastic as one would expect about its fine production values, its generally high standard of acting (particularly the performance of Geoffrey Rush as Dave) or its fluid shot construction. One can be sure that director George Whaley, despite his obvious abilities, will not have even the relatively limited opportunity provided to Longford and Hall to develop his screen craft in Australia.

Today, with Australian film receiving tens of millions of dollars of government support, we congratulate ourselves if they achieve 7% of our own box office. The rest goes through the distributor/exhibitor chains overseas. Few from the film industry have dared to speak out against the spectacle of a Labor Party falling all over itself to donate our Showground as a film studio to Fox – a Hollywood giant with no concern whatsoever for local culture, albeit perhaps an interest in a relatively cheap and highly-skilled labor force. The urbanisation of Australia is now overshadowed by the globalisation of Australia, and today’s kangaroo nationalism urges us to take our place in the Olympic marketplace and win against the odds. Where, then, in such an environment is the appeal of a rustic, rather episodic film in which Australian identity is embodied in Leo McKern and Joan Sutherland? And a bush musical at that!

In an age of modern technology, relatively few Australians engage in manual labour and our metaphorical flights take new forms. Urban Australians still regard the bush as a symbol of freedom. But the romance has been relocated; it resides within flora and fauna and majestic views. The Green Movement, whatever its well-founded environmental concerns, pulsates with an idealised and classless “Call of the Pristine Bush”. Urban workers are regarded by many as rednecks and spoilers, while the family farm is manifestly more tenuous than even the family itself. 1995 is a difficult time to be restoring social realities to a myth centred upon carving a home out of the wilderness.

Ken Hall’s Hollywood-style commercialism was scorned by many of the filmmakers of the Australian film revival. Yet, in thinking about the differing fates of the three versions of On Our Selection, I can’t help but recall his advice: “… the chief emphasis is, and must remain, not on how you make a film but on what you choose to make in the first place.”[23]ibid. Both Raymond Longford and Ken Hall were working within a living tradition; by the time George Whaley and Tony Buckley got their film to the screen that tradition had become marginalised within Australian society. This does not mean to say that the audiences which respond to the tradition are no longer there; it’s more that the dominant urban centres which set the trends are more closely concerned with “world” culture than with the culture that informs their own suburbs and hinterlands. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that sophisticated audiences despise and even fear this heritage. The lesson to be drawn from the 1995 experience is that no matter how well-made and entertaining a film may be, new forms need to be found for old history if we are to bring it to mainstream Australian audiences.

(My thanks – as ever – to film historian Graham Shirley for his invaluable advice, information, corrections of fact, and support.)

Endnotes

| 1 | Australia’s first public projection was actually 1896. |

|---|---|

| 2 | As of October, 1995, On Our Selection had taken $1.2 million at the box office, half of which has been generated from country districts where the film is going strong. (Private communication from Tony Buckley, 18/10/95) |

| 3 | This is Manning Clark’s term in his History of Australia, Vol. IV, Melbourne University Press, 1978, p. 336. |

| 4 | Stephen Alomes in A Nation at Last (Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1988) traces the forms, fluctuations and contradictions of Australian nationalism. |

| 5 | This concept of the Real Australia lives on today through ABC radio’s ‘Australia All Over – Macca on a Sunday Morning’. |

| 6 | Greenwood, Gordon (Ed); Australia, A Social and Political History, Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1955, p. 118. |

| 7 | McQueen, Humphrey, A New Britannia, Penguin, Melbourne 1970. |

| 8 | Smith’s Weekly, 7 September, 1935, p. 14. |

| 9 | The Hayseeds’ Back-Blocks Show (1917), The Hayseeds Come to Sydney (1917), The Hayseeds’ Melbourne Cup (1918), Prehistoric Hayseeds (1923 – MacDonald was unavailable) and The Hayseeds (1938 – with Tai Ordell who played Dave in 1920. MacDonald was appearing in the Cinesound films.) |

| 10 | Picture Show, 1 April, 1920, p. 44. |

| 11 | This was suggested as Longford’s view of things, ibid. |

| 12 | Tulloch, John, Legends on the Screen: the narrative film in Australia 1919–1929, Currency Press, Sydney 1981, p. 356. |

| 13 | It is difficult to be precise because of the absence of adequate documentation. It is generally thought to be 35, including two films produced in New Zealand. |

| 14 | This view appears to have been the prevailing one internationally as directors worked to overcome the theatricality of earlier silent films. Imported Hollywood director Wilfred Lucas speaking at the opening of Snowy Baker’s Oxford Street acting school advised intending screen actors, ‘Learn not to act’, Picture Show, October 4, 1919, p. 23. |

| 15 | Picture Show, 1 April, 1920, p. 32. |

| 16 | Hall, Ken G., Australian Film: The Inside Story, Sydney, 1980, p. 27. |

| 17 | Hall, Ken G. interviewed by Graham Shirley, 2/8/76. |

| 18 | ibid. |

| 19 | Economic News, 9 June 1932, p. 67 quoted in Wendy Lowenstein’s Weevils in the Flour, Melbourne 1978. Calculated on reported and unreported figures for each state. New South Wales was hit the hardest. |

| 20 | Ken Hall interviewed by Bruce Molloy, 1 June, 1977. |

| 21 | Everyone’s, 11 March, 1931. |

| 22 | Hall, op. cit. |

| 23 | ibid. |