Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) has been described as among the most influential Australian films of all time.[1]Dave Crewe, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock: Australia’s Own Valentine’s Day Mystery’, SBS Movies, 4 June 2015, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2015/06/03/picnic-hanging-rock-cheat-sheet>, accessed 30 May 2017. In 2015, when the film celebrated the forty-year anniversary of its release, David Stratton noted that it was the ‘industry’s first really major success for a “serious” film, a film that subsequently played in art house cinemas the world over’.[2]David Stratton, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’, At the Movies, ABC, 21 November 2012, transcript, <http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s3626005.htm>, accessed 30 May 2017 Similarly, ABC film critic Karen Percy commented that ‘[t]he movie set a new bar for filmmaking in Australia, using evocative lighting and camera moves to set an eerie mood.’[3]Karen Percy, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock 40th Anniversary’, ABC News, 6 August 2015, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-06/picnic-at-hanging-rock-mystery-keeps-people-guessing-40-years-on/6671684>, accessed 30 May 2017. Audiences have also recognised the film for its innovative soundtrack; according to a recent poll by the ABC, for instance, Picnic was ranked twelfth in a list of the 100 best film scores of all time.[4]See ‘Music in the Movies’, ABC Classic FM, <http://www.abc.net.au/classic/classic100/movies/#all>, accessed 30 May 2017.

Most academic analyses of Picnic have been grounded in literary, visual and theoretical frameworks.[5]See, for instance, Stuart C Aitken & Leo E Zonn, ‘Weir(d) Sex: Representation of Gender-environment Relations in Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock and Gallipoli’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 11, no. 2, 1993, pp. 191–212. While some studies have examined elements of the film’s music,[6]See, for instance, Jack Clancy, ‘Music in the Films of Peter Weir’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 18, no. 41, 1994, pp. 24–34. there has been surprisingly little investigation of its other sonic elements – surprising, because sound is a crucial and complex component of the film. The dynamics of its action seem embedded in the soundtrack; images are coloured in part by sound. Sound strategies are employed to smooth visual transitions, and bridge shifts in time and space – so necessary for the journeying and searching aspects of the narrative.

Of particular interest, and the focus of this article, however, is the way the soundtrack seeks to engage the audience unconsciously, viscerally and intellectually while, at the same time, foregrounding a preoccupation with a mythical, dreamlike, surreal and spiritually charged landscape. Moreover, the sonic identifications that were established in Picnic have influenced much subsequent Australian landscape cinema. Attending to the hitherto-neglected soundtrack presents an opportunity not only to achieve a more comprehensive film criticism of Picnic, but also to enrich the ways we address the Australian colonial experience and understand how sound can unsettle audiences and disturb their relationship to space.

Engaging the perceiver

The film revolves around the disappearance of, and search for, three teenage schoolgirls at the Hanging Rock outcrop in central Victoria on Valentine’s Day, 1900. Similarly to other iconic Australian films of the period, Picnic probes the mystery of the land and communicates the incongruity of European sensibilities and the harsh Australian landscape.

Picnic contains an unresolved narrative. There is no obvious explanation regarding the disappearance of the schoolgirls, and aside from Irma (Karen Robson), they are never found. This mode of storytelling falls within the realm of art cinema – a style that, as David Bordwell sums up, ‘defines itself explicitly against the classical narrative mode, and especially against the cause-effect linkage of events’.[7]David Bordwell, ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice’, in Catherine Fowler (ed.), The European Cinema Reader, Routledge, London & New York, 2002, p. 95. It appears, however, that early in Picnic’s production, the unresolved narrative posed a central problem for Weir – namely, how to stay true to the ambiguity of the original story, which does not contain a conventional ending, and still maintain audience participation and appreciation:

In Picnic, which involves a mystery without a solution, I knew that I had to, in a sense, mesmerize the audience, to induce in them a kind of dream state in order that they wouldn’t have the expectation of a conventional ending.[8]Peter Weir, quoted in Michael Bliss, Dreams Within a Dream: The Films of Peter Weir, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale & Edwardsville, 2000, p. 190.

As a means of ‘mesmeriz[ing] the audience’, Weir deploys a range of sound effects that transcend typical expectations of what a soundtrack should accomplish and amplify – that is, beyond the already heard and already familiar. Before looking at these unique sonic deployments, however, let us first briefly consider the conventional role of sound effects in the film.

As a means of ‘mesmeriz[ing] the audience’, Weir deploys a range of sound effects that transcend typical expectations of what a soundtrack should accomplish and amplify – that is, beyond the already heard and already familiar.

The influential sound designer Marvin Kerner outlines three key functions of sound effects in cinema: simulate reality (which refers to ‘hard sound effects’ that materialise specific visible actions that happen on screen), create illusion (which refers to off-screen sounds that do not correspond or synchronise to on-screen visual imagery, but rather create an illusion of action occurring) and create mood (which can manifest in both on- and off-screen forms, and tends to refer to creative and aesthetic-based applications that are specifically deployed in order to establish atmosphere).[9]Marvin M Kerner, The Art of the Sound Effects Editor, Focal Press, Boston, 1989, pp. 11–5.

Picnic’s use of sound effects exemplifies all three of these functions. For example, the first ensues through sounds that synchronise to footsteps, doors opening and closing, horses trotting, and so on. The second transpires in the various off-camera ambient animal and human sounds. It is, however, the third mode, and variations of this mode, that plays a significant role in addressing Weir’s initial concerns regarding audience participation and involvement. Some of the film’s sound effects help to establish mood, atmosphere, ambience and drama – for instance, wind gusts that increase in volume incrementally and help to create a sense of impending doom. Other sound effects, however, are deployed in even more unusual and inventive ways. Perhaps the most interesting of these is the sub-bass tremor sound, which is introduced during the film’s opening sequence and was generated through the manipulation and slowing down of an earthquake recording.[10]Annabel Carr, ‘Beauty, Myth and Monolith: Picnic at Hanging Rock and the Vibration of Sacrality’, paper presented at The Buddha of Suburbia: Proceedings of the Eighth Australian and International Religion, Literature and the Arts Conference, Sydney, 2004. This sound resonates at physical and visceral levels, and was used as a way of ‘access[ing] the audience’s unconscious, since this sound is supposedly part of those collective memories that we all have with respect to sounds or vibrations’.[11]Weir, quoted in Bliss, op. cit., p. 190. For Weir, the ability of the sound to connect physically and unconsciously helps to engage the viewer more deeply:

[T]his attempt was really part of experimenting with how far cinema can go in the sense of getting past the guardians of logic and freeing up and gaining access to unconscious areas and bringing the viewer into the film, having them join in its making.[12]ibid.

Similar environmental sound-effect manipulations are deployed in the soundtracks of many subsequent Australian landscape films. Take, for instance, the slowed-down and pitch-shifted sound of a magpie that was seamlessly integrated into the film score of Rabbit-Proof Fence (Phillip Noyce, 2002). However, whereas Picnic augments natural noises into dislocating, haunting and supernatural ambiences, the sound in Rabbit-Proof Fence is intended to emphasise a spiritual and cultural connection between the protagonists and the landscape they traverse.[13]Satellite Boy (Catriona McKenzie, 2012) also includes ominous earth-rumbling sounds (suggestive of tectonic plates shifting) combined with heavenly synth swells and drones. These sounds occur in conjunction with cosmological imagery such as the stars, the sun and the Milky Way (all of which are significant to Indigenous cultures and belief systems). Incidentally, Picnic, Rabbit-Proof Fence and Satellite Boy contain narratives revolving around children lost in the Australian outback – a theme otherwise known as the ‘lost-child motif’.

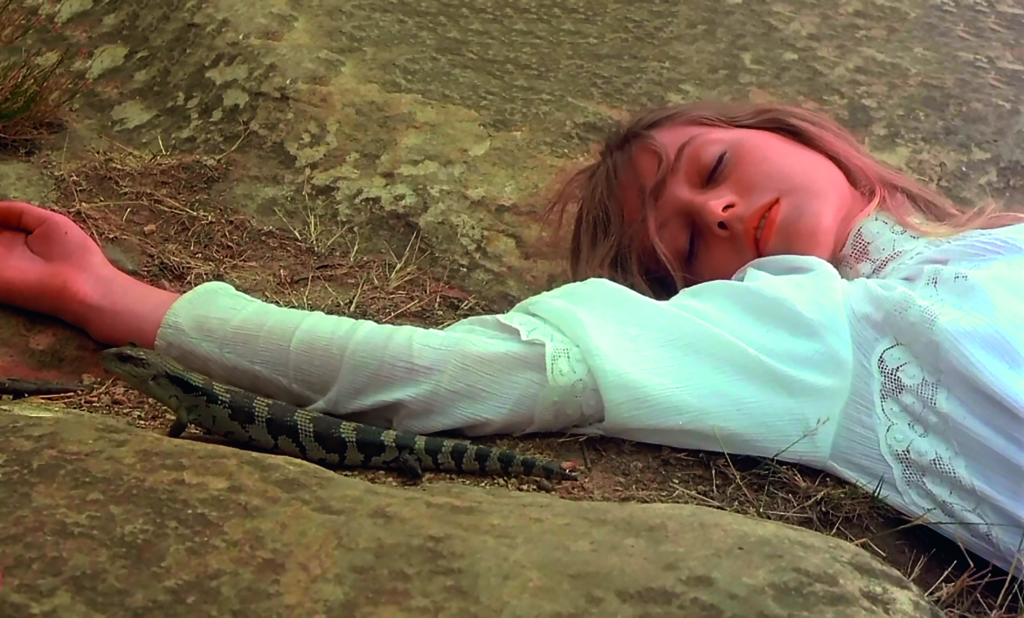

Importantly, foregrounding the natural soundscape through magnification, speed changes and filtering as a means of eliciting different psychological effects is apparent elsewhere in Picnic. Examples of such sonic alterations are evident in the highly wrought documenting of Australian wildlife intercut throughout the film’s narrative. Animal imagery is accompanied by correlating animal sounds that were recorded at an extremely close proximity to the sound source. In using such microphone configuration, the sound effect attains a kind of proximity effect, whereby there is an emphasis on bass frequencies and clarity in high-band frequencies. This method is evidenced through the closely microphoned sounds of a bird fluttering its wings, the trilling of parrots, and ants scuttling over a nest. It is extremely unlikely that one could hear such sounds in a typical exterior setting. Thus, it must be asked, why use this creative technique? What is its overall intention? And whose (acoustic) point of view is it capturing?

Although it is hard to conclude the exact reasoning behind the animal sounds, their implementation might relate to psychological themes of threat and intimacy. After all, the effects of threat, shock and affection produced in the use of visual and sonic close-ups have been well documented and identified variously as resulting from representations that are ‘jolting and excessive’, ‘aggressive’ or ‘confrontational’.[14]Per Persson, Understanding Cinema: A Psychological Theory of Moving Imagery, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003, p. 156. As the filmmaker/theorist Sergei Eisenstein noted in 1947, ‘A cockroach filmed in close-up seems on the screen a hundred times more terrible than a hundred elephants captured in long shot.’[15]Sergei Eisenstein, The Film Sense, vol. 154, trans. Jay Leyda, Houghton Mifflin, New York, 1947, p. 112. With such a scenario in mind, perhaps the same could be said about the sonic dimensions of Picnic, such as the closely microphoned sound of ants, cockatoos and flies. The highly present and confronting qualities of the sounds help to elevate the role of landscape to ‘character’, rather than simply ‘setting’; they also, as I come to explore shortly, feed into broader anxieties about the Australian landscape and Australia’s colonial past.

Here, we should also consider another related aspect of Picnic’s sound design: namely, the way it emphasises natural/environmental noises by silencing or attenuating other elements of the soundtrack. Film-music theorist Claudia Gorbman distinguishes three modes of silence: diegetic musical silence (whereby there is silence within the film world, but non-diegetic music – audible only to audiences – can be present), non-diegetic silence (when there is no music or score, but diegetic sounds can be heard) and structural silence (when a sound, previously used at a certain point, is later missing from similar places).[16]Claudia Gorbman, ‘Narrative Film Music’, Yale French Studies, vol. 60, 1980, pp. 192–4. Picnic exploits variations on these modes whereby certain elements of the soundtrack are left out – for instance, the sequence in which the girls disappear and the soundtrack quietens to near-silence, except for an amplified and synthesised moaning wind whipping through the enormous rocks. Think also of those moments before the girls vanish behind an ancient wall of stone, wherein all environmental sounds are attenuated and we hear the sound of a rock falling – a cascading, descending shiver of reverb decaying into a calm and silent atmosphere within the mise en scène.[17]Graham Reznick, ‘One Scene: Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Current, 1 August 2011, <https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1941-one-scene-picnic-at-hanging-rock>, accessed 5 June 2017. This silence is followed by the piercing scream of Edith (Christine Schuler), which permeates the surrounding space.[18]As I have argued elsewhere, foregrounding such sound effects and music in combination with atmospheric silence can be interpreted through the concept of the Australian Gothic and its associated colonial preconceptions of Australia as an unfamiliar space; see Johnny Milner, ‘Australian Gothic Soundscapes: The Proposition’, Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture and Policy, vol. 148, no. 1, 2013, pp. 94–106.

Dream sounds, dialogue and piecing together the puzzle

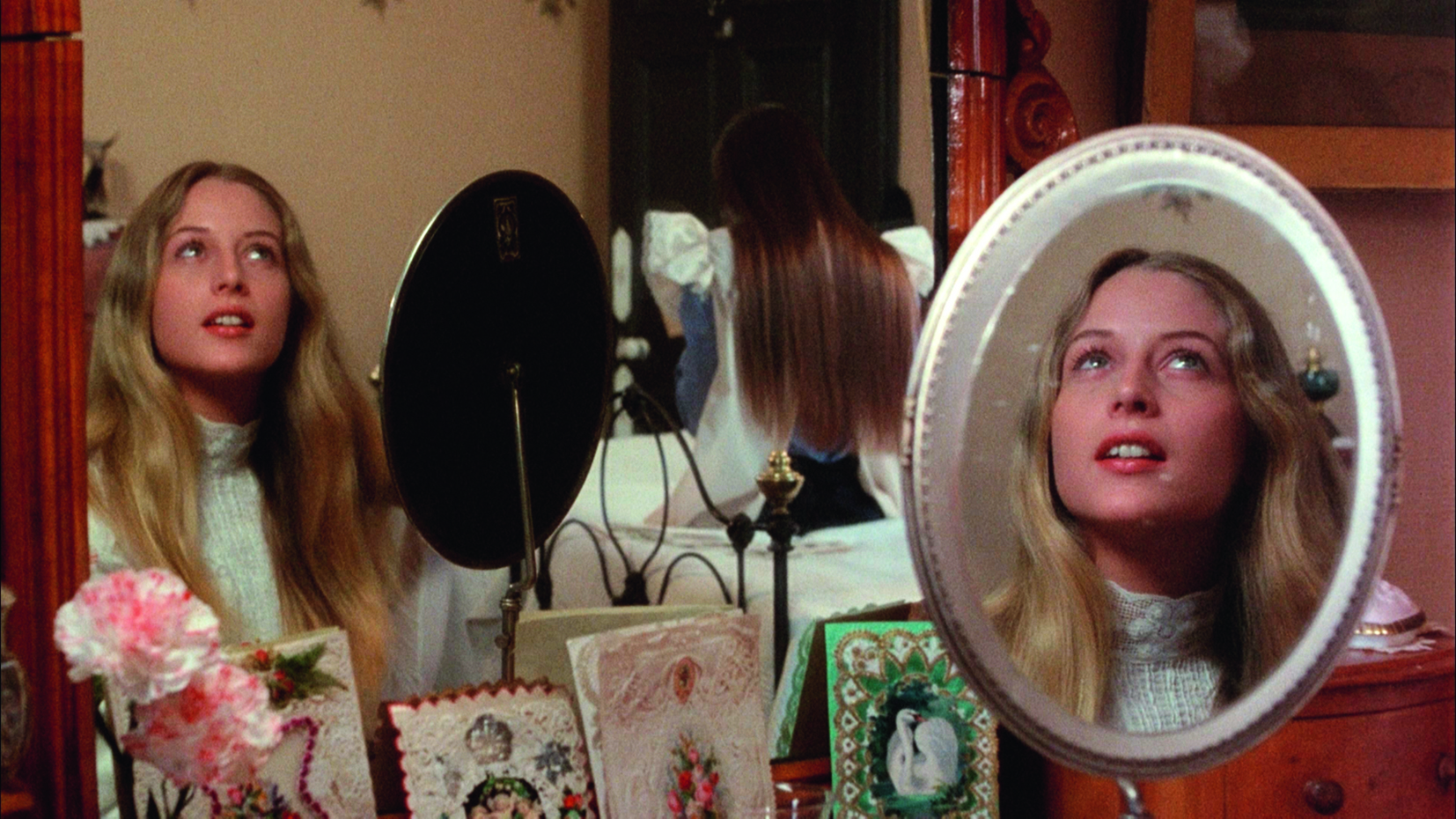

It is not only, however, the sound-effects track that helps to bring the viewer into the world of the film. Contributing in this regard are the many fragments of voiceover and diegetic poetry that combine with visual montage and overt sound effects. The fragments of dialogue assist in creating a sense of ambiguity and temporal distortion, as well as heightening the film’s surreal aesthetic. This dialogue also facilitates an unusual level of audience participation, whereby the perceiver is required to look back and reflect on what had previously been unclear.[19]David Melbye describes this as ‘retrospective dynamism’; see Melbye, Landscape Allegory in Cinema: From Wilderness to Wasteland, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010, p. 105. Such strategies are evident in sequences that feature the girls (especially Miranda, played by Anne-Louise Lambert), who ‘appear as “revenants” in frequent flashbacks’[20]Stefan Gullatz, ‘Exquisite Ex-timacy: Jacques Lacan vis-a-vis Contemporary Horror’, Offscreen, vol. 5, no. 2, March 2001, <http://offscreen.com/view/lacan>, accessed 1 June 2017. and cold-sweat nightmares subsequent to their disappearance. This effect is aptly conveyed in the scene in which Miranda manifests as an angelic figure juxtaposed – through crosscutting, overexposure and soft-focus camera techniques – over a white swan, a symbol that is frequently deployed throughout the film. The use of the white swan is curious. Is it a symbol of Miranda and her pure white innocence, or is it indicative of the destruction European culture has bestowed on Aboriginal people and the Australian landscape?[21]An example of this notion can be found in the work of Wiradjuri author, artist and activist Kevin Gilbert. In 2013, a retrospective exhibition (I Do Have a Belief) was held in conjunction with the Canberra centenary celebrations. The major piece in the exhibition, 1989’s Colonising Species, for instance, features a white swan (an emblem of European nature) clutching the neck of a lifeless black swan (an animal endemic to southern Australia), blood dripping, over the lower red half of a backdrop that seems to evoke an Aboriginal flag. See my review of the exhibition at ‘Review: Kevin Gilbert – “Distinctive” Language’, Canberra CityNews, 10 April 2013, <http://citynews.com.au/2013/review-kevin-gilbert-distinctive-language/>, accessed 31 May 2017. In this sequence, a visual flashback is cued through Beethoven’s music, and we hear the disembodied asynchronous voice of the young French teacher, Mlle de Poitiers (Helen Morse), who accompanies the girls on the picnic. Here, Mlle de Poitiers provides a distant statement that recalls an early scene in which she describes Miranda as a ‘Botticelli angel’. This scene also demonstrates a dislocation of time in the direction of myth (the angel) and earlier European history (Botticelli and Beethoven).

As with many Australian films, Picnic’s empowering of the natural, mythological landscape is at odds with the British colonialists and the rationality of the British colonial edifice. Weir is attempting to create a world of irrationality.

Similar usages of dialogue are echoed and initiated elsewhere in Picnic, such as the opening scene in which the image of the rock and the Mount Macedon landscape appear. In this scene, we hear the introductory voiceover from Miranda, who quotes a famous 1849 Edgar Allan Poe poem: ‘What we see and what we seem are but a dream. A dream within a dream.’ These words can be interpreted through Michel Chion’s concept of ‘internal sound’[22]Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, trans. Claudia Gorbman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1994, p. 76. – sound that corresponds with the physical and/or mental interior of a character (for example, heartbeats, or imagined or recollected voices). In this case, the words transcend the film’s diegetic boundaries and can be interpreted as a premonition of events that occur later within the narrative, such as that afternoon’s picnic and the schoolgirls’ disappearance.[23]Melbye, op. cit., p. 105.

In such instances, the dialogue can be read as ‘dream form’ and, similarly to those opening poetic lines, what we see and what we hear – as the audience – are dreamed content.[24]ibid., p. 147. This surreal quality is given further substance in the scene in which young Englishman Michael (Dominic Guard) searches for the missing girls at the rock and enters a catatonic dreamlike state. Here, information that he could never have known otherwise is transmitted and revealed (in aural form), allowing for the mind’s transcendence of time and space.[25]ibid., p. 105.

While toing and froing dialogue contribute to the film’s dreamlike, retrospective quality and invoke imagined and unconscious states, they also render Picnic as a complex puzzle replete with symbolism and metaphor. The film requires the perceiver to engage in solving the mystery by using the characters’ dreams and the audiovisual signage to make sense of the narrative. As with the previously mentioned sound effects, Picnic’s integration of poetic lyrics, music and stylised imagery prefigures similar audiovisual syntheses in contemporary Australian cinema. Take, for instance, The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005) and Van Diemen’s Land (Jonathan auf der Heide, 2009); both films include fragments and passages of well-known and newly written poetry to enhance their poetic and surreal qualities, as well as to foreground the starkness of the physical and colonial mental landscape.

Sonic oppositions of nature and culture

As with many Australian films, Picnic’s empowering of the natural, mythological landscape is at odds with the British colonialists and the rationality of the British colonial edifice. Weir is attempting to create a world of irrationality. This idea is reinforced through the interaction between the sounds of nature and the sounds of white culture. Bruce Johnson and Gaye Poole expand on this point in their assessment of the film: ‘the organic timeless sounds of birds, wind and insects set against the “little fidget wheels” of clocks and chimes in muted Edwardian interiors invoke the nature/culture polarity.’[26]Bruce Johnson & Gaye Poole, ‘Sound and Author/Auteurship: Music in the Films of Peter Weir’, in Rebecca Coyle (ed.), Screen Scores: Studies in Contemporary Australian Film Music, Australian Film Television and Radio School, North Ryde, NSW, 1998, p. 129.

One might also consider the previously mentioned earthquake effect, which demonstrates how sounds can undertake several important roles. This subsonic effect not only enhances audience participation through its deep resonances, but also highlights key narrative themes such as the intractability of the landscape and the broad spatial anxieties relating to Australia as perceived by the film’s white protagonists. Consider, for instance, the scene in which coach driver Ben (Martin Vaughan) and Miss McCraw (Vivean Gray) make assumptions about the age of the rock. While Miss McCraw talks about the volcanic eruption behind the rock’s formation and makes a calculated estimation of its dimensions, Ben trivialises the rock’s age. Immediately following this sequence, we see a shot of the monolith accompanied by the rumbling earthquake. The vibration heightens the irrational qualities and mythical aura given to the rock and helps to outweigh any empirical geological assessment of it. This resonating rumble is repeated with a similar effect several times throughout the film. On each occasion, from now on, the rock’s magnitude and gravity in size (both sonic and visual) correspondingly reduce the weight and significance of the human figures that come within its presence (for example, the moment when the girls are consumed by the rock and are oblivious to Edith pleading with them). The particular timing, placement and presence of this effect create a sense of the supernatural in a natural setting and renders the landscape as unstable terrain.[27]Purely as a sound effect, such usage can be linked to David Lynch’s unsettling take on US suburbia – for example, the opening scene of Blue Velvet (1986). However, unlike Lynch – whose use of such noise is decidedly not mythical – Weir sonically reinforces Australian cinema’s preoccupation with a mythical, dreamlike and spiritually charged landscape. Furthermore, it underscores the notion that European concepts of time are arbitrary and insignificant in the ancient landscape – a notion that manifests in other aspects of Picnic’s sound-effects track.

Concepts of time and timelessness are important sub-themes in Picnic. Consider, for instance, the moment when Miss McCraw’s watch mysteriously stops and we are presented with a spectacular silence, or else the ticking clock in Mrs Appleyard’s (Rachel Roberts) office, with its heavy intimations of fatality and doom. These clock sounds correlate with the noise and rhythms of the search party slapping sticks together when looking for the girls. The slapping of sticks is also a duplication of the sounds made earlier by Edith, who rapped a stick against the sides of the rock. These examples suggest a collapsing of different time schemes.[28]Bliss, op. cit., p. 51.

Moreover, oppositions between nature and culture, as well as time and timelessness, are also evident in the film’s musical workings. Consider, for instance, the film’s garden-party scene, which features the light, breezy, entertaining serenade Eine kleine Nachtmusik (by Mozart), played by a string quartet on a platform by a lake. Here, the music accompanies the formally dressed guests who ‘try to behave in a way incompatible with the laws of the new land’.[29]Marek Haltof, Peter Weir: When Cultures Collide, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1996, p. 36. As the camera pans across the guests and the well-manicured fragment of lawn, it is revealed that bush surrounds the gathering’s location. The Mozart piece contributes to the film’s aural decor by adding colour and atmosphere to the scene, but it also highlights the absurdity of European culture’s attempt to dominate and cultivate the Australian landscape.

More broadly, the use of rhythm-based as opposed to tonally based music helps to activate associated ‘oppositions between abandonment and restraint: drums versus harmony, rock versus Mozart’.[30]Johnson & Poole, op. cit., p. 129. As Marek Haltof notes, ‘the visual opposition of nature/culture (Hanging Rock/Appleyard College) has its sound equivalent in [Gheorghe] Zamfir’s “primitive” music and Beethoven’s sophisticated score’.[31]Haltof, op. cit., p. 36. Zamfir’s iconic panpipes contribute significantly in this regard because they are sharply symbolic of a pagan (perhaps even Aboriginal) world outside the Judeo-Christian norm and embedded in the mythology of the Australian landscape.[32]See, for instance, Victoria Bladen, ‘The Rock and the Void: Pastoral and Loss in Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock and Peter Weir’s Film Adaptation’, Colloquy, vol. 23, 2012, pp. 159–84; and Saviour Catania, ‘The Hanging Rock Piper: Weir, Lindsay, and the Spectral Fluidity of Nothing’, Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 84–95. Weir himself supports this idea:

You might be tempted to say, with such an ancient instrument, that it was connecting to the side of the film that was really touching on the power of nature, on the great unknown of this country, at that particular time. Here was European culture in the outback, as it were; without playing the didgeridoo – which wouldn’t have worked – it invoked, I think, a hidden world.[33]Peter Weir, quoted in Andrew Ford, The Sound of Pictures: Listening to the Movies, from Hitchcock to High Fidelity, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2010, p. 262.

However, while Weir makes the point that the didgeridoo ‘wouldn’t have worked’ in such a situation, it could be argued that the panpipes echo the Aboriginal didgeridoo.[34]For a discussion on how world music is used to evoke Aboriginality and the mythical Australian landscape, see Johnny Milner, ‘Sonic Assimilation: Exotic Soundscapes in Rabbit-Proof Fence’, Metro, no. 176, Autumn 2013, pp. 72–6. They do this by evoking through their resonance what Marjorie Kibby and Karl Neuenfeldt label a sense of ‘primitive spirituality [in] an exotic landscape’.[35]Marjorie Kibby & Karl Neuenfeldt, ‘Sound, Cinema and Aboriginality’, in Coyle (ed.), op. cit., p. 73.

Conclusion

Picnic deploys a poetic mode, conveying the limitations of Western colonial culture when confronted with the realities of the Australian outback. The film’s soundtrack is vital in highlighting this central disparity. Sounds and music are mediated and manipulated, conveying geographic and cultural dislocation – and, in doing so, engaging the audience viscerally, psychologically, emotionally and intellectually.

Reflecting on Picnic’s soundtrack forty years after its release, we see the way it has radiated across time and maintained atypical status in Australian film. We note, too, that Picnic’s sonic projection of the sublime, mythical and unknowable has been challenged recently. Think, for instance, of post-2000 Indigenous film productions such as Rabbit-Proof Fence, its soundtrack crowded with environmental sounds and music, connoting a vibrant Indigenous culture, a pre–British-settlement Australian landscape. Think, too, of the diversity of representation suggested by Samson & Delilah (Warwick Thornton, 2009), with its sonically tedious and monotonous landscape.

Nonetheless, it is clear that Australian soundtracks (old and new) are powerful modes of expression that demand continual evaluation and re-evaluation. Such a project may also prove to be of fundamental significance to our present-day challenge of securing a more productive engagement with the Australian landscape tradition and colonialism, and how these themes are represented on film.

This article has been refereed.

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/picnic-at-hanging-rock

Endnotes

| 1 | Dave Crewe, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock: Australia’s Own Valentine’s Day Mystery’, SBS Movies, 4 June 2015, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2015/06/03/picnic-hanging-rock-cheat-sheet>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | David Stratton, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’, At the Movies, ABC, 21 November 2012, transcript, <http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s3626005.htm>, accessed 30 May 2017 |

| 3 | Karen Percy, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock 40th Anniversary’, ABC News, 6 August 2015, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-06/picnic-at-hanging-rock-mystery-keeps-people-guessing-40-years-on/6671684>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

| 4 | See ‘Music in the Movies’, ABC Classic FM, <http://www.abc.net.au/classic/classic100/movies/#all>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

| 5 | See, for instance, Stuart C Aitken & Leo E Zonn, ‘Weir(d) Sex: Representation of Gender-environment Relations in Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock and Gallipoli’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 11, no. 2, 1993, pp. 191–212. |

| 6 | See, for instance, Jack Clancy, ‘Music in the Films of Peter Weir’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 18, no. 41, 1994, pp. 24–34. |

| 7 | David Bordwell, ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice’, in Catherine Fowler (ed.), The European Cinema Reader, Routledge, London & New York, 2002, p. 95. |

| 8 | Peter Weir, quoted in Michael Bliss, Dreams Within a Dream: The Films of Peter Weir, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale & Edwardsville, 2000, p. 190. |

| 9 | Marvin M Kerner, The Art of the Sound Effects Editor, Focal Press, Boston, 1989, pp. 11–5. |

| 10 | Annabel Carr, ‘Beauty, Myth and Monolith: Picnic at Hanging Rock and the Vibration of Sacrality’, paper presented at The Buddha of Suburbia: Proceedings of the Eighth Australian and International Religion, Literature and the Arts Conference, Sydney, 2004. |

| 11 | Weir, quoted in Bliss, op. cit., p. 190. |

| 12 | ibid. |

| 13 | Satellite Boy (Catriona McKenzie, 2012) also includes ominous earth-rumbling sounds (suggestive of tectonic plates shifting) combined with heavenly synth swells and drones. These sounds occur in conjunction with cosmological imagery such as the stars, the sun and the Milky Way (all of which are significant to Indigenous cultures and belief systems). Incidentally, Picnic, Rabbit-Proof Fence and Satellite Boy contain narratives revolving around children lost in the Australian outback – a theme otherwise known as the ‘lost-child motif’. |

| 14 | Per Persson, Understanding Cinema: A Psychological Theory of Moving Imagery, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003, p. 156. |

| 15 | Sergei Eisenstein, The Film Sense, vol. 154, trans. Jay Leyda, Houghton Mifflin, New York, 1947, p. 112. |

| 16 | Claudia Gorbman, ‘Narrative Film Music’, Yale French Studies, vol. 60, 1980, pp. 192–4. |

| 17 | Graham Reznick, ‘One Scene: Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Current, 1 August 2011, <https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1941-one-scene-picnic-at-hanging-rock>, accessed 5 June 2017. |

| 18 | As I have argued elsewhere, foregrounding such sound effects and music in combination with atmospheric silence can be interpreted through the concept of the Australian Gothic and its associated colonial preconceptions of Australia as an unfamiliar space; see Johnny Milner, ‘Australian Gothic Soundscapes: The Proposition’, Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture and Policy, vol. 148, no. 1, 2013, pp. 94–106. |

| 19 | David Melbye describes this as ‘retrospective dynamism’; see Melbye, Landscape Allegory in Cinema: From Wilderness to Wasteland, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010, p. 105. |

| 20 | Stefan Gullatz, ‘Exquisite Ex-timacy: Jacques Lacan vis-a-vis Contemporary Horror’, Offscreen, vol. 5, no. 2, March 2001, <http://offscreen.com/view/lacan>, accessed 1 June 2017. |

| 21 | An example of this notion can be found in the work of Wiradjuri author, artist and activist Kevin Gilbert. In 2013, a retrospective exhibition (I Do Have a Belief) was held in conjunction with the Canberra centenary celebrations. The major piece in the exhibition, 1989’s Colonising Species, for instance, features a white swan (an emblem of European nature) clutching the neck of a lifeless black swan (an animal endemic to southern Australia), blood dripping, over the lower red half of a backdrop that seems to evoke an Aboriginal flag. See my review of the exhibition at ‘Review: Kevin Gilbert – “Distinctive” Language’, Canberra CityNews, 10 April 2013, <http://citynews.com.au/2013/review-kevin-gilbert-distinctive-language/>, accessed 31 May 2017. |

| 22 | Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, trans. Claudia Gorbman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1994, p. 76. |

| 23 | Melbye, op. cit., p. 105. |

| 24 | ibid., p. 147. |

| 25 | ibid., p. 105. |

| 26 | Bruce Johnson & Gaye Poole, ‘Sound and Author/Auteurship: Music in the Films of Peter Weir’, in Rebecca Coyle (ed.), Screen Scores: Studies in Contemporary Australian Film Music, Australian Film Television and Radio School, North Ryde, NSW, 1998, p. 129. |

| 27 | Purely as a sound effect, such usage can be linked to David Lynch’s unsettling take on US suburbia – for example, the opening scene of Blue Velvet (1986). However, unlike Lynch – whose use of such noise is decidedly not mythical – Weir sonically reinforces Australian cinema’s preoccupation with a mythical, dreamlike and spiritually charged landscape. |

| 28 | Bliss, op. cit., p. 51. |

| 29 | Marek Haltof, Peter Weir: When Cultures Collide, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1996, p. 36. |

| 30 | Johnson & Poole, op. cit., p. 129. |

| 31 | Haltof, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 32 | See, for instance, Victoria Bladen, ‘The Rock and the Void: Pastoral and Loss in Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock and Peter Weir’s Film Adaptation’, Colloquy, vol. 23, 2012, pp. 159–84; and Saviour Catania, ‘The Hanging Rock Piper: Weir, Lindsay, and the Spectral Fluidity of Nothing’, Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 84–95. |

| 33 | Peter Weir, quoted in Andrew Ford, The Sound of Pictures: Listening to the Movies, from Hitchcock to High Fidelity, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2010, p. 262. |

| 34 | For a discussion on how world music is used to evoke Aboriginality and the mythical Australian landscape, see Johnny Milner, ‘Sonic Assimilation: Exotic Soundscapes in Rabbit-Proof Fence’, Metro, no. 176, Autumn 2013, pp. 72–6. |

| 35 | Marjorie Kibby & Karl Neuenfeldt, ‘Sound, Cinema and Aboriginality’, in Coyle (ed.), op. cit., p. 73. |