Jason King is not afraid of the dark. In many ways, he seeks it out. He earns his living as a security guard on long, lonely night shifts. In his spare time, he volunteers his services as a ghost hunter to Sydney residents struggling with haunted homes. He heads fearlessly into places others would never dare enter – a dark, claustrophobic crawl space apparently ripe with paranormal activity, a pitch-black drain tunnel infamously haunted by a deceased angry widow. He doesn’t do it for the money: the satisfaction of making people feel safe is enough payment for him.

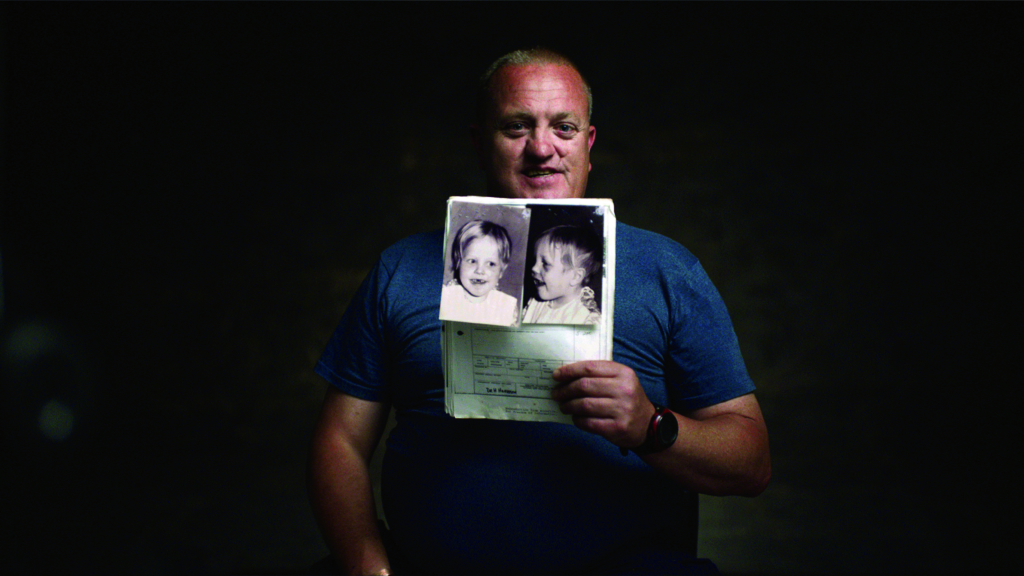

The darkness Jason himself struggles with is metaphorical rather than literal. Much of his childhood is a mystery to him, blocked out for reasons he can’t recall. His mother has refused answers, and their relationship has deteriorated and eventually dissolved. Now, only one person remains who may be able to give Jason the answers he seeks: his estranged father, a shadowy figure he remembers only in impressions. The search for the elusive John – or is it Jack, or Lynal – King started when Jason and his brother Pete wondered whether they shared a father. Jason didn’t know he had a brother until, in his twenties, Pete appeared and revealed their mother had given him up as a baby, long before Jason was born. The men quickly grew close, until Pete’s sudden death in a car crash. On the night of the funeral, amid his grief, Jason claims that he saw his first ghost: Pete, manifesting to offer consolation. After his brother’s death, Jason started hunting ghosts and became doubly determined to find his father in order to finally confirm Pete’s parentage.

It was a brief feature in a local newspaper about a ghost hunter drawn to his profession by a paranormal visit from his late brother that first attracted photographer and TV-commercial director Ben Lawrence to Jason’s story.[1]Ben Lawrence, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Ghosthunter One Pty Ltd, Ghosthunter press kit, 2017, p. 6. On the lookout for a suitable subject for his first feature-documentary project, Lawrence contacted Jason in 2010 in hopes of tagging along on a couple of ghost hunts. But the scope of the project quickly changed as Lawrence learned of Jason’s quest to find his father. By the time Ghosthunter, the feature documentary about the men’s seven-year journey together, finally premiered at the Sydney Film Festival (SFF) in 2018, its foray into the supernatural turned out to be far less haunting than the reality of what Lawrence and his team had uncovered about Jason’s childhood.

Ghosthunter, like its subject, is defined by light and shadows. Lawrence’s background in advertising shines through in the beautifully rendered images of Jason’s night shifts as a security guard, which serve to visually connect nearly a decade’s worth of footage. The distinctly film noir–inspired visuals and ominous soundtrack in these cut scenes create a sense of foreboding. They also allow Lawrence to move the story along when he does not have corresponding footage – many of the most profound revelations of Jason’s journey materialise in text messages and recordings of phone calls. It’s an elegant solution that helps set the tone for a highly complex film, which, at times, reads more like a thriller or mystery than a documentary, thanks to its tight plotting and polished, stylised visuals. Jason takes on the double role of victim and investigator, hunting for clues about his father in decades-old hospital files and battling with the revelations about his own troubled upbringing also revealed therein. Unease grows when an enigmatic woman, Cathy, contacts Jason out of the blue, claiming to have known him as a child and also on the hunt for his father. When, finally, the police get involved, it becomes apparent that the demons stirred by facts may prove more destructive than the ones summoned by the uncertainty and suffering that have haunted Jason for so long.

Ghosthunter, like its subject, is defined by light and shadows … The distinctly film noir–inspired visuals and ominous soundtrack in these cut scenes create a sense of foreboding.

As a character, Jason is easy to like, but hard to pin down. He shows incredible strength and bravery in how he tackles his horrific past, and he clearly shows great warmth and a desire to be close to family and friends. But the abuse Jason experienced as a child has scarred his adult psyche and body, and uncovering his suppressed memories at times seems akin to cutting brightly coloured wires on a ticking time bomb. It comes as no surprise when we gradually learn that the image of the happy, laid-back Sydney bloke Jason likes to project is largely a facade for a man prone to emotional outbursts and struggling with his own identity.

The film’s themes are as heavy as they are numerous, spanning childhood abuse and neglect, substance abuse, domestic violence, sexual abuse, suicide, and the ongoing and life-altering fallout caused by complex trauma. The fact that Lawrence managed to edit seven years of footage into a cohesive film that has both made such expansive topics accessible and is enjoyable to watch speaks to his skill and sensitivity as a director. The value of Ghosthunter as a tool for teaching and advocacy is immense, particularly in its nuanced exposition on the long-term effects of childhood trauma.

For documentarians, Ghosthunter also serves as a valuable case study of the power and responsibility conferred by wielding a camera. When filming vulnerable subjects, filmmakers are often required to make difficult judgement calls regarding their place within their subjects’ lives. In the case of documentary, there often remains an expectation from audiences of a certain journalistic neutrality – a detachment from subjects that allows the story to unfold as unmarred as possible by the act of recording it. Of course, this is rarely the reality off camera, especially when making films with significant social impact. Documentarians will often form deep personal relationships with the communities they depict, and play an active and crucial role in advocating for their subjects.

But this degree of connection usually develops – and is kept – behind the scenes, so Ghosthunter is a rare text for making such a relationship visible to audiences. We see Lawrence struggle with his responsibility on screen several times, but most compelling is a conversation he has with Jason while driving aimlessly around Sydney. Prior to this exchange, Jason’s sister Linda has revealed to Lawrence that Jason has a history of domestic violence, which has resulted in two Apprehended Violence Orders being made out against him by ex-girlfriends. Throughout the film, Linda and several of Jason’s friends try to confront him about his angry outbursts, suicide threats and attempts, and continued refusal to seek professional help; Jason usually shrugs them off with a joke. In the car, Lawrence confronts Jason outright with this newfound knowledge, and asks him why, after half a decade of filming together, he has never seen this side of Jason. Somehow, Lawrence gets through. Jason admits he struggles with anger and depression as well as confusion about his sense of self.

The film’s themes are as heavy as they are numerous, spanning childhood abuse and neglect, substance abuse, domestic violence, sexual abuse, suicide, and the ongoing and life-altering fallout caused by complex trauma.

Lawrence’s role as de facto custodian of Jason’s story may be what has made the difference in this situation. For one, after years of filming during some deeply personal situations, Jason will have come to know Lawrence as a close confidant who has experienced moments of great vulnerability and intimacy alongside him. For another, the documentarian’s camera acts as a sort of buffer – the relationship the men have is not quite one of work, but neither is it one of friendship. This ambiguity arguably grants Jason licence to be more open than he would be with someone he shares a close personal relationship with.

But, even now, Jason appears to deflect. Instead of acknowledging what he has done, he rambles about the struggles he has been through. Lawrence, though, is determined not to let Jason pass under the radar again. ‘But you hit those women,’ he stresses, promptly stunning Jason into silence. The atmosphere in the car noticeably changes. When Jason does not immediately answer, Lawrence continues, ‘Yeah, I’ve just heard too much to ignore it, and I’ve seen your record and all that now.’ Jason seems defensive, seems to expect that Lawrence will tell him they can no longer work together; his staccato responses betray a man trying to shield himself from the hurt of being left behind yet again. But Lawrence does not want to stop filming, and instead offers to find Jason a psychiatrist, which he readily agrees to. Shooting is interrupted for several weeks and, when it resumes, Jason seems calmer, more open and more willing to own the part he plays in his – and others’ – story.

Whether it is due to the therapy he has received, the chance to finally learn about and reconcile with his past, or the fact that he eventually finds a partner whom he feels fully supported and understood by, the Jason we see at the end of the film seems notably happier and more confident. Lawrence’s commitment to seeing Jason through his turbulent journey safely – his willingness to support his subject in any way he can – plays no small part in this successful outcome. The making of the documentary could very easily have been a catastrophically harmful process for Jason, who was and is highly vulnerable to exploitative storytelling tactics by filmmakers more unscrupulous than Lawrence.

Jason’s story could have served as the backdrop for any number of sensationalist tactics like those often seen in popular current-affairs and reality programs. Lawrence could have kept pushing Jason into emotionally volatile states to make for more dramatic sequences, or worked to manufacture conflict between Jason and his family and friends. He could have disengaged after each day of shooting and told himself that what happened as a result of their discoveries was outside his control and responsibility as a filmmaker. In the editing room, he could have chosen to tell any number of injurious stories with the same footage – the scandalous story of an abuser’s son who went on to beat women, the patronising story of a victim with no agency or hope, or even the inaccurate story of an innocent saint hard done by the world.

Then there is the actual ghost hunting. It would have been easy for Lawrence, who does not believe in ghosts, to publicly ridicule Jason and his community of paranormal enthusiasts. Instead, the filmmaker has used his footage and interviews around the topic to reveal some deep truths about Jason’s character. We don’t get to see any on-screen ghosts, but we do see a man who is willing to help people who are genuinely scared in their own homes – someone who is kind, brave, reassuring and dependable. As producer Rebecca Bennett has pointed out, ‘Whether any ghosts were actually seen or even existed didn’t really matter, the act of hunting them validates the person’s feelings and brings a form of healing.’[2]Rebecca Bennett, ‘Producer’s Statement’, in Ghosthunter One Pty Ltd, ibid., p. 7.

By capturing all the conflicting aspects of Jason, Lawrence has built a well-rounded portrait of a complex, multifaceted man with both light and darkness. And, by building a strong foundation of trust and respect – frequently checking in with his subject, and regularly consulting with psychologists and mental-health professionals throughout the production period – Lawrence was able to not only make a compelling film, but also genuinely help Jason tackle his traumas.

At SFF, Ghosthunter won the Documentary Australia Foundation Award for Australian Documentary; it also received nominations at the Sitges Film Festival and Sheffield Doc/Fest. In September last year, it received a limited theatrical release, and was released on DVD and digitally in November. Simultaneously, Lawrence and the production team have launched a social-impact campaign designed by triple-Emmy-Award-winning impact producer Jackie Turnure. The campaign aims to promote the use of the film and its accompanying materials in the training of professionals working with adult survivors of childhood trauma, raise awareness regarding trauma-related issues among the general public, and put pressure on government and other funding bodies to improve support services for survivors. June also saw Lawrence announce his next project: a feature film set among the South Sudanese community of Western Sydney, which has received support from Screen Australia and Create NSW. Despite its drastically different format and context, the so-titled Hearts and Bones is set to continue exploring many of the same themes as Ghosthunter, including ‘personal identity, the ties of family, friendship, masculinity and fatherhood’.[3]See ‘Realism the Key for New Film Hearts and Bones’, media release, Create NSW, 20 June 2018, <https://www.create.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Hearts-and-Bones-new-feature-set-to-deliver-Western-Sydney-refugee-story.pdf>, accessed 17 October 2018.

In 2010, Lawrence read an article about a ghost hunter who had lost his brother, and was intrigued to dip his toes into the supernatural in search of a good film subject. What he found instead was a man riddled by personal demons and haunted by some of the worst experiences a child could endure. Ghosthunter shows that, instead of turning away, the filmmaker sticks with Jason through all of his journey’s twists and turns. By facing the darkness with him, Lawrence helps Jason finally see the light for himself.

https://ghosthunterthemovie.com

Endnotes

| 1 | Ben Lawrence, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Ghosthunter One Pty Ltd, Ghosthunter press kit, 2017, p. 6. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Rebecca Bennett, ‘Producer’s Statement’, in Ghosthunter One Pty Ltd, ibid., p. 7. |

| 3 | See ‘Realism the Key for New Film Hearts and Bones’, media release, Create NSW, 20 June 2018, <https://www.create.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Hearts-and-Bones-new-feature-set-to-deliver-Western-Sydney-refugee-story.pdf>, accessed 17 October 2018. |