Setting the scene

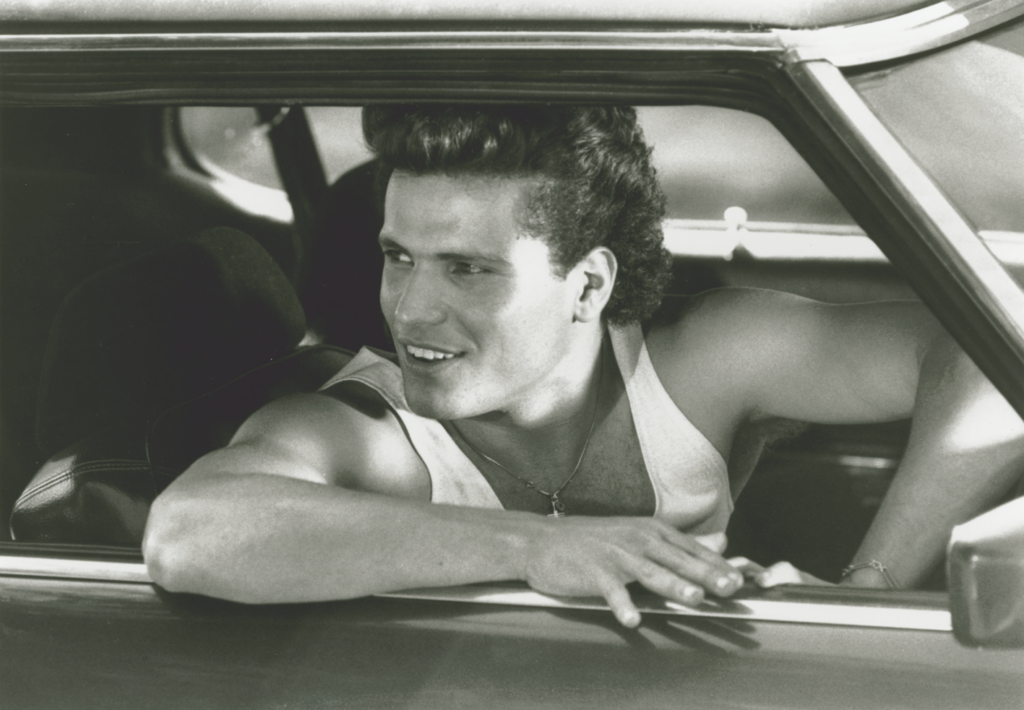

Is a car still a basic requisite for a young man’s coming of age? The emphasis may have shifted somewhat in the years since 1990; however, it is still broadly true that a set of wheels and someone special to share the front seat with is significant for many young Australians. A quarter-century since its theatrical release, The Big Steal (Nadia Tass, 1990) remains a timeless coming-of-age tale, a jaunty caper about getting a particular car and a particular girl, losing both, then winning the girl back again. In 2014, it still held enough fresh appeal for The Guardian’s Luke Buckmaster to observe that it is ‘smartly told and briskly paced – and very, very fun’.[1]Luke Buckmaster, ‘The Big Steal Rewatched – a Timeless John Hughes-esque Teen Caper’, The Guardian, 3 October, 2014, <http://www.theguardian.com/film/australia-culture-blog/2014/oct/03/the-big-steal-rewatched-a-timeless-john-hughes-esque-teen-caper>, accessed 7 March 2016.

Films about coming of age have not been inconspicuous in Australian cinema since the industry revival of the 1970s. While Hollywood usually has the target demographic – those around the same age as the lead characters – in mind, these local films have, in my view, had wider social significance in addition to capturing adolescent concerns. In the 1970s and 1980s, the coming-of-age stories that emerged on screen were as plentiful as they were diverse: a boys’ boarding school drama (The Devil’s Playground, Fred Schepisi, 1976), the tale of a young boy growing up on an isolated coast (Storm Boy, Henri Safran, 1976), stories about schoolgirls reaching maturity (The Getting of Wisdom, Bruce Beresford, 1978) and navigating the rituals of beach culture (Puberty Blues, Bruce Beresford, 1981). Elements of rites of passage were also apparent in films such as Breaker Morant (Bruce Beresford, 1980) and Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981), with the plight of young Australian men in war paralleling that of a young nation taking its place on the international stage.

Coming of age is even more intimately linked with the national narrative in certain films set at the turn of the century – around Federation in 1901 – when Australia transformed from a set of colonies and into an independent nation.[2]Jane Freebury, Dancing to His Song: The Singular Cinema of Rolf de Heer, Currency Press and Currency House, Sydney, 2015, p. 71. On the cusp of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a talented young writer opts for career instead of marriage (My Brilliant Career, Gillian Armstrong, 1979) and innocent schoolgirls face harsh and transformative new experiences on Valentine’s Day in 1900 (Picnic at Hanging Rock, Peter Weir, 1975). The treatment of coming of age in Australian film has been as an antipodean, postcolonial bildungsroman – a tale of personal growth towards maturity – that has played, at least in its earlier manifestations, into a cinema concerned with projecting Australia to the world. Perhaps the rite of passage has reflected a collective communal anxiety that Australia had not yet fully grown up.[3]Brian McFarlane & Geoff Mayer, New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, p. 183.

In the decades since, coming-of-age themes have continued unabated in Australian cinema, and have been robustly represented in Australian television serials such as the long-running Home and Away. In recent decades, coming of age in Australia’s multicultural communities has been reflected in films such as Head On (Ana Kokkinos, 1998), Looking for Alibrandi (Kate Woods, 2000), The Wog Boy (Aleksi Vellis, 2000), The Home Song Stories (Tony Ayres, 2007) and Romulus, My Father (Richard Roxburgh, 2007). Indigenous youth stories have featured in films like Yolngu Boy (Stephen Johnson, 2001), Beneath Clouds (Ivan Sen, 2002), Bran Nue Dae (Rachel Perkins, 2009) and Samson & Delilah (Warwick Thornton, 2009). Indeed, the expanding number of adolescent-themed titles in the international film industry also suggests that teen drama is a durable and expanding genre.

When The Big Steal was released in 1990, it was marketed as something to ‘steal your heart away’ – but not just young hearts. This college romance also has notable adult characters, and was ‘aimed at a very broad base audience’,[4]Timothy White, quoted in Cascade Films, The Big Steal press kit, 1990, p. 11. broader than the demographic represented by the attractive young actors whose pictures graced publicity materials. Of the film, co-producer, writer and cinematographer David Parker said just prior to its release:

We’ve tried to do a youth market story without alienating the older audixence […] I love the idea of something which appears on the surface to be a teen flick but there’s a helluva lot in it, like great characters and all sorts of issues being broached – such as justice and the study of the male in Australian society.[5]David Parker, quoted in Peter Cochrane, ‘Revved up for the Big Deal’, Spectrum, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1990, p. 75.

Notably, it was not, I feel, self-consciously encapsulating Australian identity as earlier coming-of-age films had, but rather – like other films of the early 1990s, such as The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) and Rolf de Heer’s radical revision of coming of age in Bad Boy Bubby (1993) – it was offering variations on the theme of cultural identity and the Australian male. But the need to project a national cultural identity onto the screen was simply not such an issue.

Within the envelope of the teen-comedy genre, The Big Steal is a ‘solid’ entertainment that translates well for American audiences.[6]Ben Mendelsohn, interview with the author, 29 October 2015. In his Guardian review, Buckmaster referenced the work of the late John Hughes, director of The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), and screenwriter for Pretty in Pink (Howard Deutch, 1986), seeing an affinity between the work of Tass and Parker and that of the American king of teen comedy,[7]Buckmaster, op. cit. whom critic Roger Ebert once called the ‘philosopher of adolescence’.[8]Roger Ebert, ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’, RogerEbert.com, 11 June 1986, <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ferris-buellers-day-off-1986>, accessed 7 March 2016. Hughes has been a major influence on contemporary Hollywood youth comedy, including the highly successful and prolific writer and director Judd Apatow, who has described his own work as ‘just John Hughes films with four-letter words’.[9]Judd Apatow, quoted in Pat Saperstein, ‘Director John Hughes Dies at 59’, Variety, 6 August 2009, <http://variety.com/2009/film/markets-festivals/director-john-hughes-dies-at-59-1118006975/>, accessed 7 March 2016. According to Buckmaster:

If any Australian film is the spiritual equivalent of a John Hughes movie it would have to be The Big Steal, director Nadia Tass’s 1990 puberty blues revenge romp about a brash but wily teenager who hatches an elaborate plot to get even with an oily car salesman.[10]Buckmaster, op. cit.

The Big Steal’s pop-music soundtrack also marks its youth appeal, which includes tracks by Split Enz’s Phil Judd, who contributed a number of original songs alongside band co-founder Tim Finn, as well as by The Makers, Schnell Fenster, Boom Crash Opera, Mental As Anything, Bang The Drum, The Breaknecks, Big Storm, and The Front Lawn.

Making the film

Both of the young actors cast for The Big Steal were at the beginning of their careers, in their first leading roles, though not entirely unknown on the big screen. Seventeen-year-old Claudia Karvan’s first significant appearance in a feature film was in 1987, as Judy Davis’ character’s estranged teenage daughter in High Tide (Gillian Armstrong), and that same year, twenty-year-old Ben Mendelsohn acted alongside Noah Taylor in The Year My Voice Broke (John Duigan), a break-out role that won Mendelsohn an Australian Film Institute (AFI) Best Supporting Actor award.

Husband-and-wife filmmakers Tass and Parker, were, on the other hand, already highly visible by the late 1980s. By the time The Big Steal, their third feature as producers, appeared, the Melbourne-based independent production company Cascade Films, which they created in 1983, had an established track record. Their first feature, Malcolm (directed by Tass), was released in 1986, with Colin Friels playing a socially inept and isolated tram and gadget enthusiast who becomes involved in a criminal heist. Its mechanical inventiveness, eccentric and whimsical humour, and appealing characters made it a major critical and commercial success, winning eight AFI awards including Best Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Actor. For David Stratton, it ‘seemed to come from nowhere’ and was ‘one of the happiest surprises of the decade’.[11]David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 323. The impact of Malcolm may best be summed up by australianscreen’s Paul Byrnes, who calls it ‘one of the most charming comedies of modern Australian cinema, and probably the closest we’ve come to matching the joyful silliness of Britain’s Ealing comedies of the 1950s’.[12]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Malcolm (1986)’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/malcolm/notes/>, accessed 7 March 2016.

In The Big Steal, much of the comedy derives from character and situation, and Tass was keen to find the comedy in juxtaposition by cutting between the film’s two main families, the Johnsons and the Clarks.

The Big Steal, made with local finance, was on the cusp of developments that were bringing significant structural changes to Australian cinema. In its year of production, 1989, the industry was nearing something of a tipping point. During the 1970s and 1980s, Australian films were locally produced and financed in the main, and mostly set in Australian locations. The international integration of the industry would increase during the 1990s, however, with more non-locally sourced finance and greater global involvement from project inception.[13]Tom O’Regan, ‘Beyond “Australian Film”? Australian Cinema in the 1990s’, Culture & Communication Reading Room, Murdoch University, 26 October 1995, <http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/readingroom/film/1990s.html>, accessed 7 March 2016. Indeed, Rikky & Pete (1988), the second feature by Tass (director/producer) and Parker (writer/producer), was made with backing from the major American entertainment company United Artists.

When Tass and Parker formed Cascade Films, they combined their significant talents. Tass, with her background as a theatre actor and director, had worked at Melbourne theatres the Pram Factory and Playbox. She was drawn to film for the opportunity it afforded to reach a more mainstream audience. She also professes a great love of comedy, and has no problem with the label of ‘comedy director’, relishing the challenge of making people laugh – ‘the hardest thing you can do’[14]Nadia Tass, quoted in Peter Malone, Myth & Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency Press, Sydney, 2001, p. 136. – while trying, at the same time, to say something about the world we live in.[15]ibid., p. 144. In The Big Steal, much of the comedy derives from character and situation, and Tass was keen to find the comedy in juxtaposition by cutting between the film’s two main families, the Johnsons and the Clarks.

Parker was one of the local industry’s key movie-stills photographers (with experience on major productions like Phar Lap, Simon Wincer, 1983; The Man from Snowy River, George Miller, 1982; Kangaroo, Tim Burstall, 1987; High Tide; and the TV series A Town Like Alice), and had resolved to try his hand at screenwriting after spending many long hours on set. He was also known for his work as a celebrity photographer. A photo he took of Princess Diana and Prince Charles while the couple was visiting Alice Springs in the early 1980s appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Eventually, Parker would draw on his experience as a paparazzo for his film Diana & Me (1997), a project with Toni Collette as Australian girl Diana Spencer, who wins a competition to meet her famous royal namesake. It was nearing completion when news of Princess Diana’s death shocked the world.

Parker’s talents as a writer had stepped to the fore with his screenplay for Malcolm, whose titular character was based on his wife’s late brother. Interviewed at the time, Tass said that, with Malcolm, what they were ‘really saying’ was that people with cognitive impairments have ‘a lot to contribute’ and should be valued. She then added, ‘With The Big Steal we’re saying the legal system, by its very nature, sometimes pushes individuals to take the law into their own hands.’[16]Nadia Tass, quoted in Katherine Tulich, ‘Teen Movie Could Make a Big Impact Overseas’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 September 1990, p. 88.

According to Tass, she and Parker ‘never go into production without the script in top condition’, explaining, ‘For me script is God.’[17]Nadia Tass, quoted in Mary Colbert, ‘Where Are the Scripts?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 July 1992, p. 41. The script for The Big Steal was developed over eighteen months, was initially known as ‘Mark Clark Van Ark’, and included a fourth major character, Ark. After a script assessment by the Australian Film Commission, this character was dropped and, after reviewing a list of some forty suggestions,[18]David Parker & Nadia Tass, interview with the author, 26 October 2015. the filmmakers eventually settled on the project’s new title, The Big Steal. Incidentally, it shares its name with a well-regarded American noir from 1949, directed by Don Siegel, that also involves a protagonist (played by Robert Mitchum) with some experience of being on the wrong side of the law.

The Big Steal was based on real events, notably the experience of purchasing a secondhand car. ‘Every time I buy a car I get ripped off, and that’s why I wrote it,’ Parker has explained.[19]David Parker, quoted in ‘Creative Conflict’, The Advertiser, 8 September 1990, p. 11. (Incidentally, he still buys secondhand and won’t spend more than A$25,000 on a car.[20]Parker & Tass, op. cit.) Indeed, the jacket of the DVD released by Umbrella Entertainment offers something for anyone who can relate to being ‘taken for a ride by a used car dealer’. When the couple set out to purchase a car from the proceeds of Rikky & Pete, Parker was astonished to discover that the used-car-yard experience was the same as it was when he acquired his very first vehicle:

I found nothing had changed. Despite all the regulations and Consumer Protection groups, the used car world is exactly the same as it was when I bought my first car in 1966.[21]David Parker, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 8.

While test-driving the twelve-year-old BMW they eventually bought, they noticed that the brakes squealed a bit. The salesman openly admitted that he knew he shouldn’t have kept the authentic BMW brake pads because they always squeal, and should have put in the cheap Taiwanese ones because there wouldn’t have been a problem. The line went into the film verbatim.[22]‘Creative Conflict’, op. cit.

The Big Steal was shot at many Melbourne locations, including Footscray, where the Clarks’ home was created (from a cottage that Cascade rented); Hawthorn, where the disco was located; and Collingwood for both the campus scenes and a spot where Paddy Reardon and his production-design team built an entire secondhand car yard (which they asked the crew to park their cars in). The shoot comprised six six-day weeks from early November until Christmas 1989; there were almost three-and-a-half weeks of night shoots, including some that went overnight. Mendelsohn reflected in 1997 that it was a hard shoot with long hours[23]See ‘Ben’s Brilliant Career Film by Film’, Cinema Papers, August 1997, p. 21. – especially difficult, Parker has observed, given it was summer and still light at 9.15pm.[24]Keith Connolly, ‘Could This Couple Be Hollywood’s Next Australian Discovery?’, The Sunday Age, 23 September 1990, p. 9.

A young man dreams of attaining, in no particular order, a specific make and model of car and a very particular girl … This is a story about wish fulfilment, and what really happens when you get what you long for.

Parker’s night-time camera work captures glittering lights and rain-washed city streets that were hosed especially for the effect and shot with a single camera – ‘a very pure way of working’, he says, and common practice in that era. Otherwise, the daytime shoot is characteristically ‘naturalistic, with energy and truth’, he adds.[25]Parker & Tass, op. cit. Parker has expressed his preference for an uncluttered frame: if he can reduce the number of elements in a frame, he will, to make it more succinct. What he describes as his ‘minimalistic style of photography, preferring geometric shapes’, explains his preference for the possibilities of working in the inner city. It is no surprise to hear that he once studied mechanical engineering at university.[26]Parker, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 9.

Tass and Parker had mortgaged their Melbourne home to contribute significantly to the A$1 million budget for Malcolm, a courageous gesture that prompted Stratton to praise their ‘faith and tenacity’.[27]Stratton, The Avocado Plantation, op. cit., p. 329. Finance for The Big Steal did not require such drastic measures, but the filmmakers had a lot of passion for this project, too; as Parker explained: ‘We can’t afford to make a film that isn’t absolutely our best shot. Because that’s all we’ve got going for us […] We felt that this was a film we could go out on a limb for financially.’[28]Parker, quoted in Cochrane, op. cit. Thirty-five per cent of the A$2.5 million budget was provided by private investments, and the balance came from the Australian Film Finance Corporation. Parker suggests that getting the project up was not without its challenges, even after the significant success of Malcolm: ‘Either we are not very good deal-makers or it’s difficult for financiers to understand my scripts’.[29]ibid.

A domestic release was delayed until the film had been screened overseas. The Big Steal was shown to audiences in England, where it won The Projectionists’ Golden Sprocket Award at the London Film Festival, and in Japan. It was released in most European countries as well as in the then-USSR (it screened in Moscow in 1989, and Tass and Parker like to say that it ‘brought Russia to its knees’[30]Parker & Tass, op. cit.) and South America. It had screenings but did not have a theatrical release in the US. It was distributed in Australia by Hoyts.

What the film was about

A young man dreams of attaining, in no particular order, a specific make and model of car and a very particular girl. Neither are within easy reach. This is a story about wish fulfilment, and what really happens when you get what you long for.

The Big Steal opens in suburbia, on the trim and modest weatherboard cottage that is home to the Clark family. It is bathed in the soft light of late afternoon; a caravan is parked in the driveway, with the gleaming towers of Melbourne’s central business district rising skywards in the distance. It’s a romantic, tranquil moment before the frame is bisected by a train thundering past along the railway line directly behind the cottage, obliterating the city skyline for a brief instant before tranquillity returns.

Inside the home, there is a father-and-son discussion underway, a gentle homily about one’s place in life, which one would not imagine is the first such discussion between the two. It is introduced by a self-consciously traditional voiceover that eventually segues into the voice of the father. Danny Clark (Mendelsohn) is clearly not taking any notice as his father, Desmond (Marshall Napier), standing at the bedroom door in his denim dungarees, tries to instil ‘some sense’ into his boy. With an English working-class accent, Desmond warns Danny that the Jaguar the boy longs for is ‘out of his class’, and he should stop ‘all this nonsense’ about owning a such a car. But, like the colonialist upstart that he is, Danny will not accept such humbling advice from his ‘new chum’ dad. Inattentively, he continues to stroke the sleek model Jag on his lap. Danny’s bedroom is a temple to his obsession – he is a true ‘tragic’. The walls are plastered with posters, pages from magazines and automotive engine diagrams, a leaping big-cat hood ornament among them. It was back in the day when the looks of individual makes of cars were far more distinctive than the differences between badged brands are today. Dashboard items crowd the shelves.

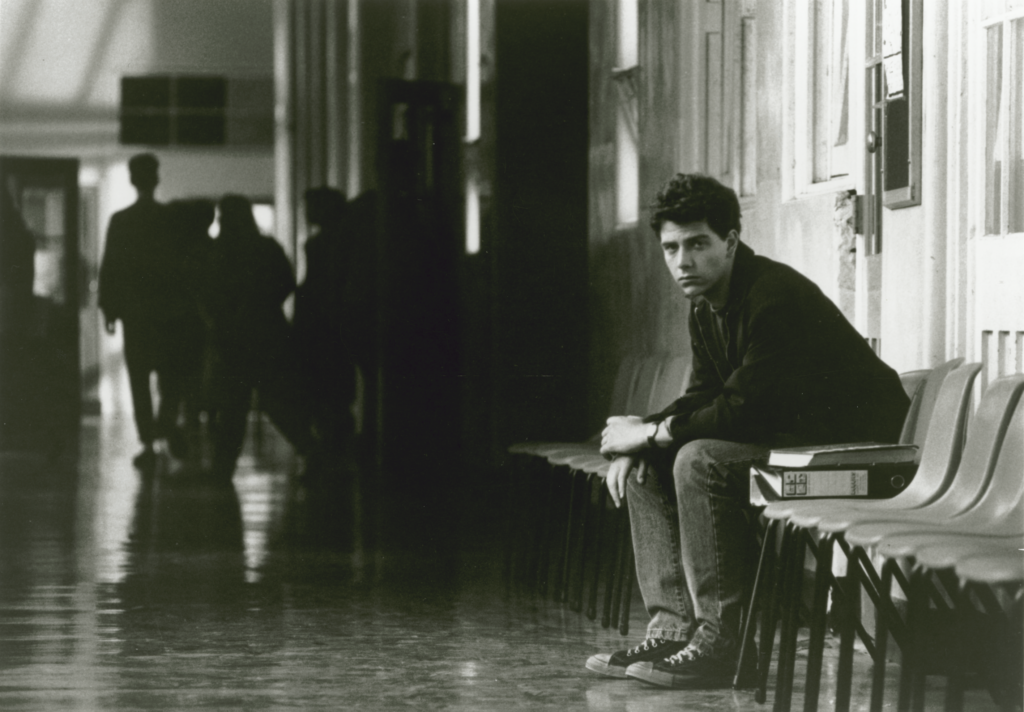

Should Danny really know his place? Of course not, and he will pursue the quest. He is ‘all class and no brass’ – a phrase used by Mendelsohn’s mother, which the actor feels is an appropriate way to describe his upstart character.[31]Ben Mendelsohn, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 14. Danny’s preference for quality and style, as he sees it, extends to girls who may be unattainable, too, and it is what he hopes they will see in him. In fact, the narrative, a traditional quest, has dual objectives that unfold in parallel stories: Danny is also infatuated with Joanna Johnson (Karvan), a crush that he has had difficulty acting on. His serious-minded, bespectacled friend Mark Jorgensen (Damon Herriman), a character that would be known today as the ‘nerd’, attempts to do so on Danny’s behalf at college but fails miserably, forcing Danny to directly ask Joanna to go on a date.

It’s another false start when, after racing up several flights of stairs at college to meet Joanna as she comes out of the lift, a breathless Danny blurts out an invitation that involves picking her up in a car he does not have. Very uncool. It’s a long way from the theatre of the school corridor in American college films, where the lead characters strut their stuff, walking three or four abreast – a motif of the American teen film. All the more absurd that one critic finds in Tass and Parker’s film a ‘brat-pack’ plotline![32]Farrah Anwar, ‘The Big Steal’, Monthly Film Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 687, April 1991, p. 100. Joanna is ‘not really into cars’, she says, and when we get to know her family background, it is easy to understand why. However, with the invitation to a date accepted, Danny believes he needs to be as good as his word and pick her up in a Jaguar.

All of these events take place before the opening credits have even finished, in a jaunty compression of narrative information within several minutes. When the final credit appears for Tass as director, Danny has arrived home from school in the red Monaro driven by his mate Vangeli ‘Van’ Petrakis (Angelo d’Angelo).

Danny is eighteen, and it won’t be too long before he considers leaving home. However, he is not the only one on the threshold. His retiree parents, Desmond and Edith (Maggie King), are simultaneously preparing to leave on a motoring holiday. They are ready to pull away from their parental responsibilities with a caravan trip to Port Campbell, but is the time right? If Danny is not quite ready to launch yet, he will prove his mettle in the ensuing narrative, showing that he is well clear of the ‘failure to launch’ comedy of adult children unable to leave home, which has become something of a subgenre in itself since 2000.

As Danny enters the kitchen with Mark and Van, they are met by Edith, in a silly party hat, who produces a three-tier birthday cake. If he is a bit embarrassed by this, he will be even more embarrassed by his birthday present. Late afternoon on Danny’s birthday, Desmond is to be found out the back putting finishing touches to the bondwood caravan. Seen in dungarees or dressing gown, he is an amiable, supportive and non-threatening dad if ever there was one. Danny’s birthday present is a hand-me-down 1963 Nissan Cedric, the family sedan. His father has replaced it with a red Nissan Pintara, which looks like it has the horsepower better suited to towing a caravan – but also more of a young man’s car. For all his modesty, it could be that Desmond has a touch of midlife crisis. His new car is clearly visible in the distance when ‘penis’ and ‘envy’ appear together on the Clarks’ Scrabble board.

Danny enjoys special attention from his parents, including a little ritual at the mention of his name: is he Daniel the lion-tamer or Daniel their son? They always fondly agree it is the latter. One of the delights of The Big Steal is that each of the secondary characters, from the adolescents to the adults, has a distinguishing quirk or two. The contrast between the Clarks, with their Anglo-Australian eccentricities, and the outside world is integral to the comedy.

With a few deft touches, the costume department also hints broadly at Australia’s emerging multiculturalism. Danny wears a T-shirt with Japanese lettering and a rising sun, while Van, conceived affectionately in Tass’ words as a ‘typical macho wog’,[33]Nadia Tass, ‘Audio Commentary by Filmmakers Nadia Tass and David Parker’, special feature, The Big Steal, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2003. wears a T-shirt inscribed with Greek lettering. Indeed, in the second edition of his influential study of Australian narrative cinema, National Fictions, Graeme Turner included this Tass and Parker title among a clutch of early 1990s films whose generic structure, urban setting or narrative closure complicated the patterns he had identified earlier. Like other Australian films of the period – Proof (Jocelyn Moorhouse, 1991), Death in Brunswick (John Ruane, 1990) and Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992) – The Big Steal showed a direct interest, Turner observed, ‘in the richness and diversity of contemporary Australian society’.[34]Graeme Turner, National Fictions: Literature, Film and the Construction of Australian Narrative, 2nd edn, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1993, p. 153.

Representations of Australian masculinity on screen were also beginning to change in the early 1990s. In the aforementioned films and others such as The Heartbreak Kid (Michael Jenkins, 1993), which were moving away from monocultural, Anglocentric representations and towards figures of varying ethnicities, academic Philip Butterss subsequently found a tension between conventional narratives and the changing patterns of masculinity in contemporary Australian society, which offered a fresh take on the construction of male identity in local film.[35]Philip Butterss, ‘Becoming a Man in Australian Film in the Early 1990s: The Big Steal, Death in Brunswick, Strictly Ballroom and The Heartbreak Kid’, in Ian Craven (ed.), Australian Cinema in the 1990s, Frank Cass Publishers, London & Portland, 2001. There is certainly a noticeable shift from the uniformly dominant representation that was to be seen in, say, The Year My Voice Broke.

The Big Steal has managed to combine romance and caper comedy with considerable panache. It works as both an exuberant comedy, with teenagers outwitting corrupt adults … and as a romance about two beautiful young people from different worlds.

A confident lad of Greek descent, Van is popular with the girls and is able to entice them into the back of his car, embodying a view – popular at the time – that ‘the easiest way to attract a woman is with a powerful set of wheels’. He also knows a lot about the inner workings of cars. If the film’s criticism of adolescent macho behaviour overlaps, as Butterss suggests, with ethnic stereotyping,[36]ibid. then Van is not the only one: everyone, including the Clarks with their British ways, gets a gentle serve in this good-natured romp.

On his quest to impress the lovely Joanna, Danny cruises the city’s car yards. ‘Car of the week’ at Geoff Mullens Motors is an XJ6 in racing green – just the car he is looking for. He has some savings and, after trading in the Cedric, will be better placed to buy, though it rather depends on what salesman Gordon Farkas (Steve Bisley) – a figure of fun in boofy hair, gold neck-chain and white socks visible beneath trousers that hang too short – decides to let it go for. Gordon is a very compelling villain. For all of the comedy at his character’s expense, it was important to Bisley that he be seen as a credible and successful small businessman: ‘Gordon thought he was for real.’[37]Steve Bisley, interview with the author, 2 November 2015.

Whatever the deal that is on offer, Danny is hooked, and Farkas need hardly remind the young enthusiast that he is buying ‘a piece of motoring history’. Despite his mother’s reassurance that the Cedric was his to do with what he wanted, it seems that Danny could not anticipate the intensity of his father’s reaction to the loss of the family car, a treasured possession since Danny was an infant. Desmond’s pain is a cry of anguish, a primal scream captured with a 360-degree dolly as a train happens to roar past – very un-British, though it was apparently the same when the family budgerigar died. When Desmond’s anger is spent, Edith advises him to go inside so as not to catch cold. Perhaps the Clarks’ eccentricities really are, as The Sydney Morning Herald’s Lynden Barber observes, ‘the outward expression of the comprehensively bonkers’.[38]Lynden Barber, ‘Stealing Pays off’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 September 1990, p. 12.

Having managed the purchase, Danny arrives at the Johnsons’, an incongruous McMansion in the middle of Melbourne’s western suburbs, to pick Joanna up and take her to the disco. He brings a bunch of flowers and is half an hour early, but his eagerness and friendliness are immediately rebuffed by Joanna’s surly and hostile father, Desmond Johnson (Tim Robertson), a plumbing contractor responsible for the toilets at the establishment where the young couple are headed that evening. Danny struggles to process this information and find an appropriate response. Joanna’s father remains deeply suspicious. If Danny so much as lays a finger on his daughter, there won’t be any second date – ‘Did he tell you not to touch my breasts?’ Joanna asks Danny in front of her father before they leave. In my view, Butterss’ suggestion that Mr Johnson’s threats expose a struggle with ‘incestuous desires for Joanna’[39]Butterss, op. cit., p. 86. is a subtext for another film, perhaps; this father figure is clearly a pathological control freak.

Unaccustomed to such poisonous family dysfunction, Danny tries to work out how he fits in where the father is a bully; the son, a likely clone; and the mother, a doormat – but with a daughter somehow independent of it all. Karvan sees her character as probably ‘consciously trying to create another path’ from her odious family. In aspiring to stress Joanna’s individuality, Karvan wanted her character to wear decorative cowboy boots, ‘a clue to her unique personality’, to ‘offset the generic “love interest” role she performed’.[40]Claudia Karvan, interview with the author, 27 October 2015. But Joanna is no slave to fashion, either. Her girlfriends reflect the late 1980s’ fashions, with discreet tattoos, flamboyant clothes and hair that ‘so clearly define the period’.[41]Tass, ‘Audio Commentary by Filmmakers Nadia Tass and David Parker’, op. cit. At the disco, they rush over, rudely ignore Danny and try to persuade Joanna to join them for a cocktail. How could she possibly be there with the unremarkable Danny? She turns them down and asks Danny to take her to a place of his choosing. They end up riverside, sharing fish and chips, and in this idyll of peace and harmony, Danny is able to confess it is his first date.

Unfortunately, the evening that was going so well turns into a nightmare when Danny succumbs to the challenge of a drag race at the traffic lights. The dream date turns into a nightmare when the Jaguar breaks down and Joanna’s dress is spurted with oil. Furious that Danny took the shallow challenge, she stalks off, yelling, ‘Little boys and big cars. You’re all the bloody same!’ It’s yet another point at which Danny has to call his ideas of masculinity into question. This critique of base machismo sets the plot in train for another concern: settling scores with secondhand car salesman Gordon. The plot then turns into a revenge fantasy about getting back at the slick operators who have squeezed credit from unsuspecting customers, turning it ‘into Australia’s new national sport’.[42]Jim Schembri, review of The Big Steal, Cinema Papers, no. 81, December 1990, p. 53.

Danny’s return to the car lot the next day, with Van for moral support, makes for another interaction with the execrable Gordon. The confrontation prompts the odious salesman to a new low. He won’t listen to any of Van’s opinions – ‘Listen, sonny, when I want a pig, I’ll rattle a bucket’ – and insults him with derogatory language (‘loud-mouthed dago’, ‘greaseball’) that was, unfortunately, all too familiar to those who can recall the days before multiculturalism changed the face of Australia. The exchange in the car yard is astonishing by today’s politically correct standards. Van has only a few milder insults up his sleeve: ‘You’re a rip-off merchant!’ Gordon then agrees to make good the problems with Danny’s Jaguar, but there will be a ten-month wait! Having forged his father’s signature on the contact, Danny has lost his right to recourse, and the stage is set for retribution and the big steal.

Back home at the Clarks’, the mood has shifted. Desmond and Edith are in the backyard practising tai chi under the Hills Hoist, in an effort to restore Desmond’s equilibrium after the shock of losing the Cedric. In the tete-a-tete between father and son that follows, Danny hears that his father once learned fitting and turning with Joanna’s dad at Collingwood Tech College. This revelation shows that, despite the Johnsons’ ostentatious two-storey brick home, XJ6 Jaguar and other trappings, Desmond Johnson and Desmond Clark have more in common than one would think besides the same first name. They are indeed ‘not so far apart’,[43]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘The Big Steal (1990)’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/big-steal/notes/>, accessed 7 March 2016. and it brings social pretension into focus. Be genuine, true to yourself and honest in your dealings. The Big Steal’s message is as age-old as Polonius’ advice to his son, Laertes, in Hamlet, Shakespeare’s coming-of-age tragedy: ‘to thine own self be true’.[44]William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 3. With the help of his parents and a new girlfriend who has no time for surface appearances, Danny will learn it, too.

And now to Gordon Farkas, who is also exposed for what he is: a covert voyeur who visits adult book and video outlets, and who spends entire evenings watching ladies mud-wrestling. Even so, the discovery that he is a cross-dresser is a completely unforeseen surprise. When police pull Gordon over and he emerges from his car in lace panties, fishnet stockings and red high heels, it is a great comic moment. Tass and Bisley, who was well known for his action roles in the late 1980s, came up with the idea for this hidden side to Gordon’s character while in rehearsal.[45]Bisley, op. cit. And, although we despise his impoverished moral and ethical framework, I think it is possible to feel a little empathy for Gordon after the entirely unforeseen revelation.

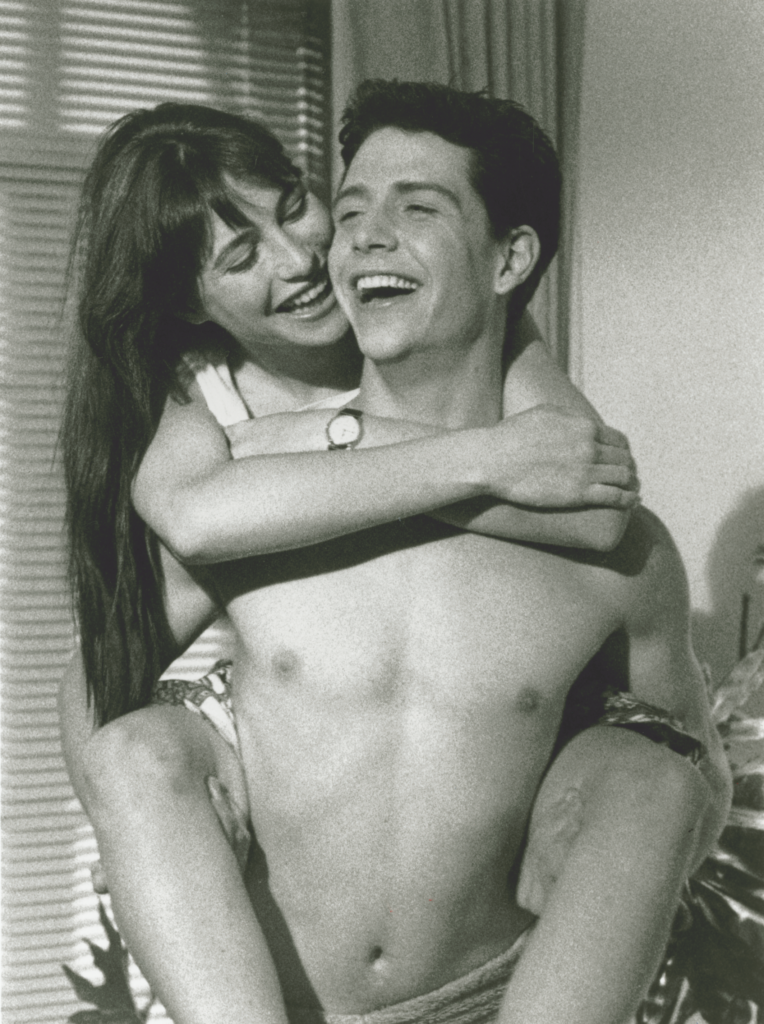

With the proper engine restored to his XJ6, Danny roars up to Joanna’s place in the early hours of the morning. Emboldened by his revenge on Gordon, he summons Mr Johnson with a megaphone. Joanna emerges in a nightgown on another balcony, a modern-day Juliet to Danny’s Romeo. Indeed, Danny’s origins on the wrong side of the tracks may have even inclined Joanna to give him a chance. It is not safe to hang around, and Danny roars off declaring, ‘I love you, Joanna!’ There is just a bit more to sort out before they can drive away together, and the narrative concludes in classic resolution: with the two young people as a couple.

The extended chase sequence in which Danny and Joanna escape in the Cedric and caravan, leaving Gordon to his fate at the hands of Desmond Johnson and his plumber mates, and then the police, is skilfully handled – and very funny. In a homage to the classic narrative, all loose ends are tied in the concluding montage, with everyone enjoying their just deserts, including Danny when the lights go out in the caravan and he and Joanna consummate their love. The Big Steal has managed to combine romance and caper comedy with considerable panache. It works as both an exuberant comedy, with teenagers outwitting corrupt adults, ‘complete with car chases and a touch of mayhem’, and as a romance about two beautiful young people from different worlds ‘trying to find their way into the adult world’.[46]Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘The Big Steal (1990)’, op. cit. By the end of Danny’s quest, he has emerged from his parents’ world, exposed the criminal activities of the used-car yard – where, in the view of many Australians, the lowest of low professions is conducted – and eluded those who would do him harm in a chase through the city streets. Finally, the boy-gets-girl / boy-loses-girl problem is resolved, but in a completely different way from what Danny envisioned. After a series of misadventures and with the help of enterprising friends Van and Mark, Danny has extricated himself from the mess he created and finds himself in Joanna’s arms.

Owning an impressive car had next to nothing to do with his good fortune and, ultimately, the fact that Desmond Johnson is also a Jaguar driver has given Danny ‘some perspective on his own aspirations’.[47]ibid. Finally, The Big Steal reveals what Joanna and Danny have in common, brushing aside the trappings of class or social status that had kept them apart.

What audiences thought

Tass and Parker took The Big Steal to Cannes in May 1990 and eventually released it theatrically later that year. It was a significant critical and commercial success in the home market. In particular, Barber praised the ‘unashamedly mainstream’ film, describing it as a combination of adolescent rites-of-passage film and comic caper ‘with charm to spare’.[48]Barber, op. cit. Released in the same year as Hollywood blockbusters like the Tom Cruise vehicle Days of Thunder (Tony Scott) and the sequels to Gremlins (Joe Dante) and Die Hard (Renny Harlin), The Big Steal still managed to do very good business at the Australian box office. It achieved a local gross of A$2.4 million, making it the second-highest-grossing local film of 1990, after The Delinquents (Chris Thomson), which had a box office of A$2.6 million. The Big Steal would become the fifth-highest-grossing local title over the 1989–1991 three-year period.[49]Screen Australia, ‘Top Five Australian Feature Films in Australia Each Year, and Gross Australian Box Office Earned That Year, 1988–2014’, <http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research/statistics/boxofficeaustraliatop5.aspx>, accessed 7 March 2016.

Mendelsohn had, at one point, been attached to appear in The Delinquents opposite pop singer Kylie Minogue, but the part eventually went to American actor Charlie Schlatter, who was considered likely to have more international appeal. The Big Steal did well to stand up to the Minogue and Schlatter vehicle, especially considering that both Mendelsohn and Karvan, while already appearing in film and on television, were still relative unknowns.

Overseas, The Sunday Times wrote that Tass and Parker’s film was ‘a deliciously quirky comedy which zeroes in on some of the more obviously obnoxious aspects of Australian society’. As the reviewer put it: ‘The loud-mouthed, beer-swilling ocker comes under strong fire, as does the air-headed bimbo, peer group pressure and the pretentious class rituals of the nouveau riche.’[50]Ingrid Jacobson, ‘Aussie and Hilarious’, The Sunday Times, 23 September 1990. The character Barry McKenzie, the boorish Australian abroad, had indeed cast a long shadow! In contrast, a somewhat-condescending review by Farrah Anwar in the former British Film Institute publication Monthly Film Bulletin objected to the apparent absence of a forthright political or social agenda, complaining that Danny’s final rejection of the XJ6 had more to do with ridding himself of a bad purchase ‘than a repudiation of materialism and sexual aggrandisement’.[51]Anwar, op. cit. Closer to home, Australian critic Jim Schembri wrote rather begrudgingly that, although it had ‘plenty of homespun philosophical appeal’, ‘easy charm’ and ‘simple warmth’, The Big Steal was ‘not a film to get deep about’. He admitted to some contradictory feelings about its success, but added that it was ‘great to see such an unpretentious, well-made, straightforward, crowd-pleasing Australian film filling the theatres’.[52]Schembri, op. cit., pp. 53–4.

Stratton, writing for Variety, was also won over by its appealing ‘low-key charm […] and a couple of riotously funny scenes’, venturing that Australian adolescents ‘are incredibly unsophisticated compared to 18-year-olds in Hollywood teen comedies’ but then admitting that was part of the film’s charm.[53]David Stratton, review of The Big Steal, in Variety Film Reviews, 1989–1990, vol. 21, R.R. Bowker, New Jersey, 1991. Perhaps he had romantic comedies like Pretty in Pink or Say Anything… (Cameron Crowe, 1989) in mind.

The Big Steal received nine AFI nominations, including for the award of Best Film, but lost to another coming-of-age drama, Flirting (1991), directed by John Duigan, his follow-up to The Year My Voice Broke. The Best Director award went to Ray Argall for Return Home (1990), another film in which both Mendelsohn and Frankie J Holden (who played Gordon’s colleague and partner in crime, Frank, in The Big Steal) appeared. Parker won the AFI award for his screenplay, which was then published, with a foreword by David Williamson, by University of Queensland Press in 1991. The other two awards won by The Big Steal were for Best Original Music Score (for Phil Judd) and Best Supporting Actor (Steve Bisley).

Mendelsohn may have had some misgivings about his casting as Danny in The Big Steal – he did not think, at the time, that he was suited to the comedy[54]Mendelsohn, interview with the author, op. cit. – but there have been so many other local films, from Idiot Box (David Caesar, 1996) to Hunt Angels (Alec Morgan, 2006) to Beautiful Kate (Rachel Ward, 2009), in which he has portrayed very different personas. Yet it was David Michôd’s thriller Animal Kingdom in 2010 that brought him (and fellow veteran thespian Jacki Weaver) to the attention of the international industry. Michôd wrote the role of a menacing criminal ‘specifically for Mendelsohn, trying to capture his “raw and untamed” qualities’.[55]Elissa Blake, ‘Raw Talent’, The Sydney Magazine, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 2010, p. 34. Animal Kingdom has since ushered opportunities for the actor to take up significant supporting-actor roles in big international productions such as Killing Them Softly (Andrew Dominik, 2012) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (Ridley Scott, 2014), as well as in Netflix series Bloodline, for which he received Emmy and Golden Globe nominations.

Cascade Films has continued successfully in independent production. Notable films from the company after The Big Steal include Amy (1997), which won twenty-eight international awards and also featured Mendelsohn, and Matching Jack (2010); both of these films were directed by Tass. Other titles include the 1993 three-part miniseries Stark, written by Ben Elton for the BBC and ABC, as well as features for other writers and directors.

Tass and Parker’s first three features were distinctive comedies, ‘quirky’ before the word became an overworked descriptor of Australian films. It is difficult to pinpoint when the use of the word ‘quirky’ in relation to local cinema began – it may have started in the US – but, in the early 1990s, the word was fresh and helped to describe films such as Sweetie (Jane Campion, 1989), Muriel’s Wedding (PJ Hogan, 1994) and Priscilla, as well as television series such as Round the Twist, whose episodes were partly based on Paul Jennings’ book Quirky Tails.

The Cascade comedies Malcolm, Rikky & Pete and The Big Steal represent a distinctive moment in Australian cinema. The Tass–Parker husband-and-wife creative partnership produced a unique and jaunty variant of ‘quirky’ comedy that combined the Ealing comedic spirit in 1950s British cinema with the zest of Hollywood teen romantic comedy, ultimately breaking new ground for Australia on screen.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Philip Butterss, ‘Becoming a Man in Australian Film in the Early 1990s: The Big Steal, Death in Brunswick, Strictly Ballroom and The Heartbreak Kid’, in Ian Craven (ed.), Australian Cinema in the 1990s, Frank Cass Publishers, London & Portland, 2001.

Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘The Big Steal (1990)’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/big-steal/notes/>, accessed 7 March 2016.

Cascade Films, The Big Steal press kit, 1990.

Peter Cochrane, ‘Revved up for the Big Deal’, Spectrum, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1990, p. 75.

Mary Colbert, ‘Where Are the Scripts?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 July 1992, p. 41.

Jane Freebury, Dancing to His Song: The Singular Cinema of Rolf de Heer, Currency Press and Currency House, Sydney, 2015.

Peter Malone, Myth & Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency Press, Sydney, 2001.

Brian McFarlane & Geoff Mayer, New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992.

Tom O’Regan, ‘Beyond “Australian Film”? Australian Cinema in the 1990s’, Culture & Communication Reading Room, Murdoch University, 26 October 1995, <http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/readingroom/film/1990s.html>, accessed 7 March 2016.

Jim Schembri, review of The Big Steal, Cinema Papers, no. 81, December 1990, p. 53.

Screen Australia, ‘Top Five Australian Feature Films in Australia Each Year, and Gross Australian Box Office Earned That Year, 1988–2014’, <http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research/statistics/boxofficeaustraliatop5.aspx>, accessed 7 March 2016.

David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990.

Graeme Turner, National Fictions: Literature, Film and the Construction of Australian Narrative, 2nd edn, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1993.

MAIN CAST

Joanna Johnson Claudia Karvan Danny Clark Ben Mendelsohn Gordon Farkas Steve Bisley Desmond Clark Marshall Napier Edith Clark Maggie King Vangeli Petrakis Angelo D’Angelo Mark Jorgensen Damon Herriman

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1990 Length 99 minutes Production Company Cascade Films Director Nadia Tass Writer David Parker Producers Nadia Tass, David Parker Co-producer Timothy White Cinematographer David Parker Composers Phil Judd, Chris Gough Editor Peter Carrodus Production Designer Paddy Reardon

Endnotes

| 1 | Luke Buckmaster, ‘The Big Steal Rewatched – a Timeless John Hughes-esque Teen Caper’, The Guardian, 3 October, 2014, <http://www.theguardian.com/film/australia-culture-blog/2014/oct/03/the-big-steal-rewatched-a-timeless-john-hughes-esque-teen-caper>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Jane Freebury, Dancing to His Song: The Singular Cinema of Rolf de Heer, Currency Press and Currency House, Sydney, 2015, p. 71. |

| 3 | Brian McFarlane & Geoff Mayer, New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, p. 183. |

| 4 | Timothy White, quoted in Cascade Films, The Big Steal press kit, 1990, p. 11. |

| 5 | David Parker, quoted in Peter Cochrane, ‘Revved up for the Big Deal’, Spectrum, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1990, p. 75. |

| 6 | Ben Mendelsohn, interview with the author, 29 October 2015. |

| 7 | Buckmaster, op. cit. |

| 8 | Roger Ebert, ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off’, RogerEbert.com, 11 June 1986, <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ferris-buellers-day-off-1986>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 9 | Judd Apatow, quoted in Pat Saperstein, ‘Director John Hughes Dies at 59’, Variety, 6 August 2009, <http://variety.com/2009/film/markets-festivals/director-john-hughes-dies-at-59-1118006975/>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 10 | Buckmaster, op. cit. |

| 11 | David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 323. |

| 12 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Malcolm (1986)’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/malcolm/notes/>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 13 | Tom O’Regan, ‘Beyond “Australian Film”? Australian Cinema in the 1990s’, Culture & Communication Reading Room, Murdoch University, 26 October 1995, <http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/readingroom/film/1990s.html>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 14 | Nadia Tass, quoted in Peter Malone, Myth & Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency Press, Sydney, 2001, p. 136. |

| 15 | ibid., p. 144. |

| 16 | Nadia Tass, quoted in Katherine Tulich, ‘Teen Movie Could Make a Big Impact Overseas’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 September 1990, p. 88. |

| 17 | Nadia Tass, quoted in Mary Colbert, ‘Where Are the Scripts?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 July 1992, p. 41. |

| 18 | David Parker & Nadia Tass, interview with the author, 26 October 2015. |

| 19 | David Parker, quoted in ‘Creative Conflict’, The Advertiser, 8 September 1990, p. 11. |

| 20 | Parker & Tass, op. cit. |

| 21 | David Parker, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 8. |

| 22 | ‘Creative Conflict’, op. cit. |

| 23 | See ‘Ben’s Brilliant Career Film by Film’, Cinema Papers, August 1997, p. 21. |

| 24 | Keith Connolly, ‘Could This Couple Be Hollywood’s Next Australian Discovery?’, The Sunday Age, 23 September 1990, p. 9. |

| 25 | Parker & Tass, op. cit. |

| 26 | Parker, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 27 | Stratton, The Avocado Plantation, op. cit., p. 329. |

| 28 | Parker, quoted in Cochrane, op. cit. |

| 29 | ibid. |

| 30 | Parker & Tass, op. cit. |

| 31 | Ben Mendelsohn, quoted in Cascade Films, op. cit., p. 14. |

| 32 | Farrah Anwar, ‘The Big Steal’, Monthly Film Bulletin, vol. 58, no. 687, April 1991, p. 100. |

| 33 | Nadia Tass, ‘Audio Commentary by Filmmakers Nadia Tass and David Parker’, special feature, The Big Steal, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2003. |

| 34 | Graeme Turner, National Fictions: Literature, Film and the Construction of Australian Narrative, 2nd edn, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1993, p. 153. |

| 35 | Philip Butterss, ‘Becoming a Man in Australian Film in the Early 1990s: The Big Steal, Death in Brunswick, Strictly Ballroom and The Heartbreak Kid’, in Ian Craven (ed.), Australian Cinema in the 1990s, Frank Cass Publishers, London & Portland, 2001. |

| 36 | ibid. |

| 37 | Steve Bisley, interview with the author, 2 November 2015. |

| 38 | Lynden Barber, ‘Stealing Pays off’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 September 1990, p. 12. |

| 39 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 86. |

| 40 | Claudia Karvan, interview with the author, 27 October 2015. |

| 41 | Tass, ‘Audio Commentary by Filmmakers Nadia Tass and David Parker’, op. cit. |

| 42 | Jim Schembri, review of The Big Steal, Cinema Papers, no. 81, December 1990, p. 53. |

| 43 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘The Big Steal (1990)’, australianscreen, <http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/big-steal/notes/>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 44 | William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 3. |

| 45 | Bisley, op. cit. |

| 46 | Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘The Big Steal (1990)’, op. cit. |

| 47 | ibid. |

| 48 | Barber, op. cit. |

| 49 | Screen Australia, ‘Top Five Australian Feature Films in Australia Each Year, and Gross Australian Box Office Earned That Year, 1988–2014’, <http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research/statistics/boxofficeaustraliatop5.aspx>, accessed 7 March 2016. |

| 50 | Ingrid Jacobson, ‘Aussie and Hilarious’, The Sunday Times, 23 September 1990. |

| 51 | Anwar, op. cit. |

| 52 | Schembri, op. cit., pp. 53–4. |

| 53 | David Stratton, review of The Big Steal, in Variety Film Reviews, 1989–1990, vol. 21, R.R. Bowker, New Jersey, 1991. |

| 54 | Mendelsohn, interview with the author, op. cit. |

| 55 | Elissa Blake, ‘Raw Talent’, The Sydney Magazine, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 2010, p. 34. |