It is impossible to speak of any election campaign in Australia without acknowledging the enormous impact the media has on its conduct and on the ways in which the campaign is understood. Most people get most of their political information on a daily basis from the media. A majority would also concede that the role of the media is vital in shaping perceptions about key personalities and policy issues central to any campaign. In some instances, it is even vital to the eventual outcome of that campaign. The purpose of this article is to outline a number of background issues surrounding the media coverage of the 2007 Australian federal election campaign in order to assess the significance of the media’s role.

Political journalists and reporters regularly remind Australian voters how important an upcoming federal election really is. For them, and the mainstream media outlets, the seemingly dominant message is that the result will irrevocably change the course of Australia’s future direction and culture. It is hard to think of a federal election where this hasn’t repeatedly been stated by media commentators. For those who were there and can remember, it’s hard to go past the famous ‘It’s Time’ 1972 campaign which saw Gough Whitlam break twenty-three years of Coalition government with a popular Labor Party victory, aided in no small measure by universally enthusiastic media endorsement and approval. The consensus among media commentators was that William McMahon’s government had become stale, had run out of new ideas and was rudderless after the resignation of long-standing prime minister Robert Menzies and the disappearance of his successor Harold Holt. In leading editorials and opinion pieces, influential print media argued strongly that it was indeed time for a change.

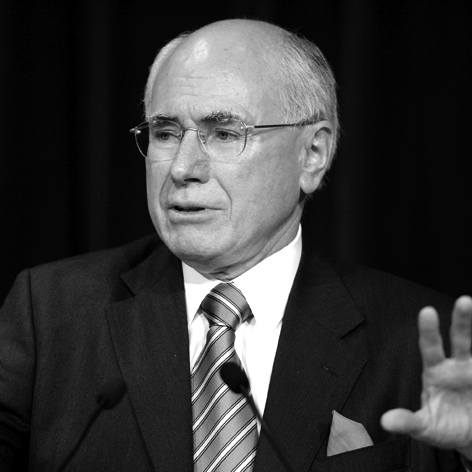

So too, in 2007, there was some gathering momentum in many media reports for political change. This perception was shaped to some extent by still important and influential sectors of the print media. Again there seemed to be a growing consensus in many feature articles, opinion pieces and some Fairfax editorials that prime minister John Howard had lost touch with the Australian electorate. The widely held perception was that having been in power for eleven years, Howard was now implementing policies that were cumulatively becoming more unpopular with growing sectors of the electorate.

The fascinating aspect about this was that well before the official campaign began there were some unexpected calls for Howard to stand down from his position in favour of his treasurer, Peter Costello. These calls were coming in from well-known Howard supporters from Rupert Murdoch’s stable of newspapers (Janet Albrechtsen, Paul Kelly and Andrew Bolt). Had they been getting word from on high? Could He see the writing on the wall for Howard? For the totally cynical, the question was whether Murdoch and Rudd’s recent and well-publicized private lunch in New York was in fact a very successful prime ministerial job interview.

Polls and more polls

The first point which needs to be made in an assessment of media coverage of any election is that the importance and significance of media commissioned polling cannot be overstated. These frequently published polls not only indicate the very latest swings and roundabouts in public voting intentions, but also come to affect the political agenda itself – as well as the tone of reporting and analysis which follow.

In 2007 these polls increasingly put the Coalition forces on the defensive. Some Coalition backbenchers started to openly question key policy initiatives. Some became worried about the unpopularity of the radical component of industrial relations policy contentiously referred to as ‘WorkChoices’. Some even began to speculate that there ought to be a last-minute change in leadership with treasurer Peter Costello replacing Howard.

The importance and significance of media commissioned polling cannot be overstated.

At the same time, the more positive poll findings for Labor helped make the party cautiously optimistic. The prevailing mood inside Labor circles was that after eleven years, the electorate was simply tired of the Howard government. With the national economy in relatively good shape, it seemed to key Labor insiders that the party could only win by playing it safe. Effectively, they were arguing that Labor could not differentiate itself too far away from Howard Government policies.

In the past, other poll findings had brought about moves from within party ranks to challenge the party leadership. This had occurred federally in cases involving Kim Beazley, Simon Crean, Bill Hayden, Andrew Peacock, Alexander Downer and, in the 1980s, Howard himself. Poll findings have also undermined innumerable state leaders and have even helped in the determination of policy initiatives.

Clearly, polls are increasingly powerful in their own right and media audiences are implicitly told to trust their veracity. What is indisputable is that media commentators refer and defer to polls constantly in reports and when making their own analysis.

For the year since Kevin Rudd assumed leadership of the ALP from Kim Beazley, the almost weekly publication of poll findings were analysed and dissected by all major media outlets. Whether they were fully media-commissioned findings such as the Age poll, NewsPoll or Galaxy poll (or well-established independent organizations such as Roy Morgan and Nielsen) these polls were more often than not pointing to a solid Labor victory.

Politics has become a kind of blood sport in the way it has been represented by so many segments of the media. Australians love their sport and the media feed them ongoing stories of victories, defeats, dramas, leaders and strategies.

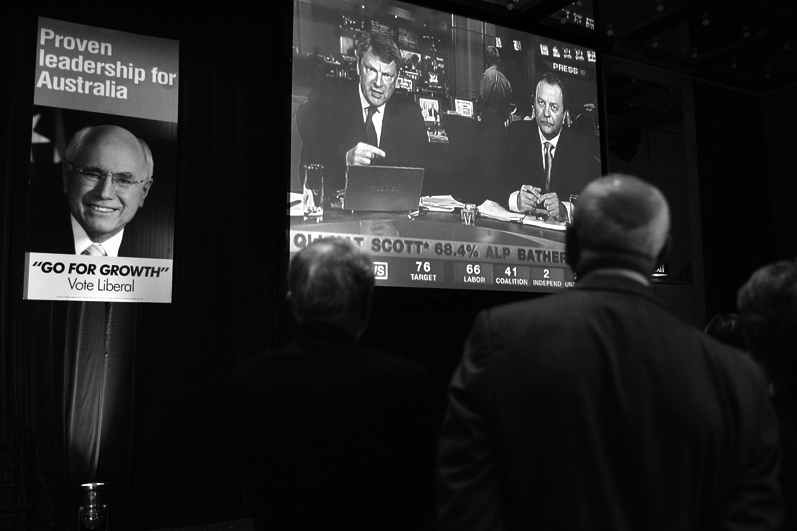

Every reputable polling organization states that there is a statistical margin of error of between one and two per cent on their findings. Political operatives, media commentators and their audiences are more poll driven than ever. Yet there are some political operatives who maintain that not all polls are accurate measures of public opinion. Some polls have been wrong while rival polling groups have reported conflicting results. On the day prior to the 24 November 2007 election, Galaxy and Newspoll predicted a narrow two-party preferred result of 52–48 to Labor. This result made it possible to speculate that Labor might not gain the sixteen seats it needed to form government. On the same day, the Age poll published a 57–43 two-party preferred result and predicted a landslide victory to Labor.

The traditional argument in representative democracy is that leaders should lead and not be poll driven. On the other hand there is a double-pronged defence of the wide use of internal party polling that says it is not only strategic to do so, but also that it fulfils a democratic principle in the purest sense. As their representatives in parliament, political leaders need to listen to their electorate – and come to understand what it is thinking. This is an ongoing and evolving debate. For those who advocate constant polling there are wider issues which must be addressed. In order to generate their collective opinions, from where did the electorate get their information? How reliable was this information? How much information did the electorate not receive due to the media’s propensity to set agendas by omitting relevant material? We need to come to an understanding of how media-commissioned polls and leaked internal party polling affect the overall media coverage of election campaigns.

Politics and sporting contests

The general level of excitement surrounding elections is largely generated by mainstream media organizations. For many mainstream outlets, such as free to air, pay-TV, the twelve capital city and national newspapers, and talk radio stations around the country, the immediate lead-up to the election was an event not dissimilar to that of an AFL grand final. Major national events such as these are usually good for television/radio ratings, press circulation figures and web site hits.

In reporting these events, individual media workers covering national politics get the opportunities to make a name for themselves by breaking that all-important scoop, getting that all-exclusive leak or exposing the latest political gaffe. Politics has become a kind of blood sport in the way it has been represented by so many segments of the media. Australians love their sport and the media feed them ongoing stories of victories, defeats, dramas, leaders and strategies. By nature, political and sporting events produce winners and losers; the personalties, strategies and tactics are fascinating components in the ongoing struggle to win. All of these are delicious components in the reporting of stories. Both political and sports commentators have reflected publicly that their own adrenalin gets pumping and their sense of excitement and purpose grows as we head towards that ultimate showdown.

Television reporters knew that their role in covering this election was crucial because most people still gain most of their political information through that medium.

Most political journalists and reporters, especially those who form the Canberra press gallery, look forward to peaks in the level of excitement in their work. During 2007, after covering an increasingly predictable political leader for eleven years – one who (for some at least) was not overly stimulating in the first place – a change might be seen as most welcome. The same was true, probably even more so, for many television reporters. Television reporters knew that their role in covering this election was crucial because most people still gain most of their political information through that medium.

One of the first to recognize this shift in our media landscape was Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, who had the foresight to predict in the early 1960s that in the new television age the emphasis on personalities would become the dominant aspect of political coverage. Television reports put far more emphasis on the human dramas surrounding personalities in the political arena than on hard policy issues.

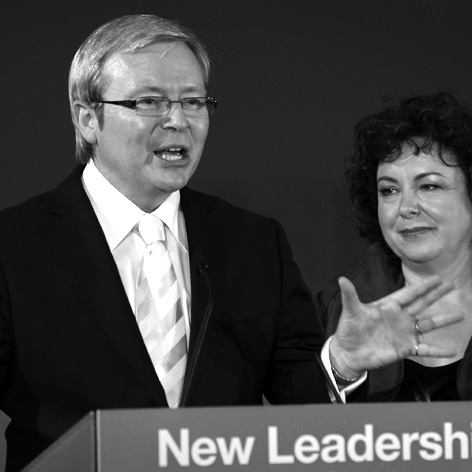

The possibility of a ‘changing of the guard’ story, the time for a new face, came to play a significant role in many media reports from early December 2006 – when Rudd replaced Beazley as leader of the Labor Party. John Howard had already won four elections in a row, including one where he easily defeated the hapless Beazley. Howard was now the second longest-serving prime minister after Robert Menzies.

Here we had the makings of a real contest and a gripping human interest story. A new Opposition leader was in place, yet in late 2006 Kevin Rudd was not all that well known. He was seemingly very different in style and temperament to his predecessors, the affable but lacklustre Beazley and the more volatile Mark Latham. It must be remembered that Latham had also helped create some media excitement when he first became leader of the Labor Party. He had successfully challenged Simon Crean, someone widely perceived by the media as being rather bland. This is what McLuhan had intended when he spoke of the importance of personalities over policies in television reports on the political process.

The gladiatorial American presidential election system has become our de facto political model despite the maintenance of the British parliamentary system.

There is also no doubt that journalists and reporters look forward to election campaigns when more charismatic, challenging and unpredictable characters emerge on the political scene. They can write more interesting profiles. More unexpected things happen. More people take an interest in what is going on when the human interest factor is maximized.

This is how the Australian political system and its reporting has become far more American over the past two to three decades. The gladiatorial American presidential election system has become our de facto political model despite the maintenance of the British parliamentary system. The human qualities and persona of the leader of the party is now, more often than not, more important than the actual policies being pronounced. This is increasingly how politics is being reported by mainstream media and, therefore, largely perceived by most Australian voters.

New media laws: cross-media ownership

Another factor we need to keep in mind when looking at media coverage of the 2007 federal election is that this was the first campaign held since media ownership regulations had been radically altered by (the now former) communications minister Senator Helen Coonan. Commercial media outlets did not spend much time or effort critically examining the ramifications of the abolition of both the cross-media and foreign ownership restrictions (which had been in place since 1987). The virtual dynastic fiefdoms of Murdoch, Packer and Fairfax were enthusiastic and long-time supporters of the lifting of the restrictions. With this, their victory was now enshrined in legislation.

The lifting of the restrictions would irrevocably change the media landscape. Television station owners could now own major newspapers in the same capital cities. Alternately, newspaper owners could now own television stations, and each category could now buy radio stations. For major commercial media players this represented a real opening up of the market. Under the new legislation, there would also be no formal limits to foreign owners.

Media theorists who took the position that the media always had some power to shape agendas and public opinion would now be even more concerned with greater concentration of media power. The power to set agendas would now be more systematic and comprehensive.

Yet these familiar theoretical and ideologically driven arguments were considered to be outdated, irrelevant and illogical according to Coonan, Howard and even former communications minister Senator Richard Alston before them. A counter argument had been well developed and went something like this: the new age of multi-channelling, digital television and the Internet (itself with associated applications such as blogs and popular sites such as MySpace and YouTube) all meant that media diversity was now a fact of life and here to stay. Any talk of the power of old media barons such as Murdoch, Fairfax and Packer was now truly anachronistic.

The death of PBL magnate Kerry Packer in late 2005 and the seeming indifference to the old family media empire by his only son and major inheritor, James, further indicated that there was merit in the claim that media moguls were no longer a force. James Packer has in fact sold seventy-five per cent of the family empire to a foreign equity group and has acquired some more gambling institutions. Interestingly, James Packer has recently teamed up with Lachlan Murdoch to form an intriguing new alliance to head the remains of the Packer media empire. As with Foxtel and the failed One.Tel venture, it creates a link between two of the oldest and most powerful names in Australian media.

With Senator Coonan’s new media legislation, foreign equity corporations could now play a more dominant role in shaping Australian media organizations and this would arguably also work to enhance diversity and plurality of voices and opinion. In this process ‘a thousand flowers could now bloom’ (from an infamous Mao Zedong quote) and the 2007 federal election would be noteworthy because of the increasingly important role played by a more diversified and interactive new media. As a consequence of this, it was argued that there would be a corresponding increase in diversity of opinion and analysis which truly reflected a plural society. With these changes, the democratic process was being well and truly served.

New media in the 2007 campaign

There is no doubt that in this election new media in general, and YouTube, MySpace, various blog sites and ‘alternative’ online domains (like Crikey and newmatilda.com) in particular, played an increasingly important role in delivering political online content. Interestingly, John Howard’s primary forays into YouTube seemed to have backfired in that his political video messages made for the youth-orientated web site were mocked by many who watched and responded to his messages.

It was clear that Howard looked uncomfortable and spoke in his customary formal manner, which did not fit with the more carefree and casual nature of YouTube. It must be said that Kevin Rudd’s efforts on YouTube were less newsworthy because they did not attract as much criticism. Yet, while these and other web sites were full of political content and plenty of opinions, more often than not they were reporting and commentating on stories already broken by the mainstream traditional media sources.

In essence, traditional daily newspapers still provided detailed information and political content and analysis leading up to the election. Talk radio stations supplied plenty of content as politicians seemed keen to be interviewed by the talkback hosts. Television news and current affairs programs (especially on the ABC and SBS) continued to provide an ample amount of commentaries and news to political junkies.

It must be acknowledged that survey findings on the popularity of Internet sources indicate that it is still very low. Roy Morgan research published in 2007 points to the fact that around fifty-three per cent of people get most of their news and current affairs from television. A further twenty-one per cent rely on hard copy newspapers while seventeen per cent receive most of their news from radio. The final nine per cent of the electorate rely primarily on the Internet to get most of their political information. It will be most interesting to see how much this changes in the next decade.

A strong case can be made that newspapers – and there are now only twelve capital city and national papers in the country – still help set agendas for other media forms. This is especially true for radio – whose talkback hosts rely heavily on newspaper reports, as do the producers of current affairs television programs. If all media outlets have a form of symbiotic relationships between each other, then newspapers still have a dominant role because they employ more journalists and reporters to create content.

There is no doubt that radio and television have heavily cut back on their human resources on the news desks. What is also noteworthy (and ironic) is that while news-papers still lead and feed other media forms, overall circulation figures continue to fall, a fact which is a worldwide trend with most dailies.

In coming to terms with the debate about the significance of the Internet in creating more diversity, there is no dispute that over the last few years the circulation figures of newspapers and overall audience numbers watching television are falling while Internet usage has increased dramatically. Yet it is still difficult to maintain that the rise in Internet usage actually translates a rise in the level of diversity and opinion.

This is the main argument that technology optimists use when talking about the breakdown of the old media monopolies. This was the main argument used by those who advocated the dropping of all cross-media ownership restrictions in 2006. The Internet would indeed ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’.

The reality of the situation, however, is really quite different. And for critics of commercial media conglomerates, it is not altogether surprising. It was never going to be the case that old media moguls – especially mega-successful ones like Rupert Murdoch – were not going to invest heavily in online sites. This involvement goes well beyond Murdoch acquiring MySpace for a cool US$580 million in 2005.

A worldwide trend has seen established media operators and nearly all major newspaper conglomerates effectively go online. This has provided a huge amount of online material created directly by journalists and reporters already working for their hard copy editions. Maybe this is becoming a case of ‘better the devil you know’ because when web sites are measured (as they can so easily be by visit counts as well as by surveys), they consistently reveal that mainstream sites are by far the most popular ones chosen by members of the public who go online.

Again, Roy Morgan research indicates that for Australian news and current affairs the ‘usual suspects’ were well up there on the most visited lists. So ninemsn.com.au, news.com.au, fairfax.com.au and abc.net.au are dominant. This fact has been corroborated by other research conducted by Margaret Simons and Alan Kohler. It is claimed that around eighty to eighty-five per cent of accessed online content is being provided by the established media organizations – indeed the visits count for Crikey and newmatilda.com did not even rate a mention in the survey findings.

The claims made about the huge diversity in opinions that the Internet has opened up are (at least up until now) premature. Yes, the Internet contains literally millions of independent sites, blogs and discussion groups. Yet the fact of the matter is that most people rarely make regular use of them as they surf around the well-known and established media brand names.

Swinging and uncommitted voters

Many political theorists and media analysts have long agreed that the tone and content of media coverage leading up to an election can play a significant role in influencing swinging, undecided and uncommitted voters. In recent Australian elections it has been variously estimated that the number of swinging and undecided voters has now reached between twenty and thirty per cent of the electorate. This is a much higher figure than the five to ten per cent which was the generally agreed-upon percentage allocated to those type of voters in the 1970s and 1980s.

The issue here is the crucial role the media play in providing up-to-date political news, commentaries and information to swinging, uncommitted and undecided voters. Whatever the actual number of these voters, most Australian federal elections since the 1960s have resulted in total swings between the two major parties of between one to five per cent. Indeed any swing over six to seven per cent in two-party preferred terms is described as a landslide. If a substantially larger proportion of voters consider themselves, and are judged to be, swinging, undecided or uncommitted voters, then the question of where and how they get their information in order to finally decide how to vote becomes even more critical.

Spin doctors and media control

Major political parties work assiduously in an ongoing campaign to garner public support. They know full well that this can only be realistically achieved if media reports on their activities are relatively positive. The 1996 federal election saw a shift in the way political parties approached the media. It was a process that was well overdue as far as the political parties were concerned. The role of public relations within the marketing sphere had long been applied in the worlds of corporate business and finance, but an increasing importance was now being attached to the creation of minders and spin doctors in political parties. The upper echelons in the parties saw a need to recruit media-trained and savvy professionals who could subject the media to different pressures in order to get the ‘right’ messages out.

The spin doctors would work to help control the information which was going out on mainstream media outlets. Their job was to ensure that all of the information about the party on any given day had a positive slant. In this important way, a counter force was developing against the media to modify the free flow of information.

The methods used by these new media liaison officials included working on increasing the frequency of pre-prepared press handouts, briefings and statements which became a more controlled way of channelling information. There has been a dramatic reduction in direct questioning and open-ended forums to focus on key policy areas.

The PR and advertising experts hired by political parties also had a vital role in selling the messages from the party to the electorate. The 2007 campaign created a new record (estimated at over $100 million) for the amount spent on the official six-week campaign. On top of this, in the lead-up to the election there were the government-sponsored ‘announcements’ and ‘information campaigns’ on the implementation of WorkChoices, which was estimated to cost over $120 million.[1]The Age, 28 November 2007, p.5.

The Labor Party was also heavily into PR marketing hype when the 2007 campaign opened. The slogan ‘Working Australian Families’ became a catchcry for nearly all domestic policies introduced by Rudd or any of his shadow ministers. PR and advertising are now central instruments in the creation of political reality. Increasingly, the language used to persuade us to buy consumer goods throughout the year become the same as those used to persuade us to vote for one party rather than another at election time.

In general terms, the main goal for key party officials now is to ensure that a positive item become ‘the grab’ or ‘sound bite’ that will lead the news. This is more often than not a well-rehearsed piece but it helps ensure that there is less unsolicited questioning and hopefully less opportunity for the dreaded political gaffe.

The 2007 election campaign was highlighted by some reporters now trying to keep tabs on how many gaffes had been committed (Peter Garrett, Tony Abbott, Nicole Cornes and, on the day before the election, Jackie Kelly were the obvious standouts.) Yet the way in which the election campaign had descended to tightly controlled scripts (with spin doctors literally working overtime) had basically changed the nature of political campaigns.

There are strong arguments suggesting that the electorate – and ultimately the democratic process – has been short-changed in this. Party officials reduce direct questioning and public access to politicians, and thus limit the opportunities of journalists and reporters to do their job.

In this situation, the Australian political system has been weakened, and is nowhere near the more open and transparent American model. There, in the lead-up to the US national conventions through the primary and caucus ballots held in the fifty states, reporters have far more opportunities to ask questions and follow-up questions without notice, while members of the public are much freer to ask direct questions to political candidates.

This adds up to an increasingly prevalent and disconcerting notion that political discourse in Australia is being shaped more and more by two opposing forces. On the one hand, the political players and their minders are becoming increasingly cautious of overly exposing their major candidates to the often confrontational and sensationalist tabloid media. At the same time, and in trying to counter this, media corporations are often involved in reporting elections not merely to provide information, but in order to affect outcomes in particular ways.

The major campaign issues

This was an election where a large number of media commentators and political analysts observed that as the campaign progressed, there were few major differences between the policies of the Coalition and the Labor Party. There was nothing really new in this convergence of the two major parties as veteran observers had been noting this trend since 1983 with the Hawke/Keating governments.

This is not to say that there were no differences. Symbolic issues such as Australia signing the Kyoto Protocol, reconciliation with Indigenous Australians (and an official apology), initial dates for the withdrawal of Australian troops from Iraq and opposing policies on the controversial WorkChoices legislation were clearly matters of important policy differentiation.

Yet, during the campaign period, even on the contentious industrial relations front, the changes the ALP sought to the obviously unpopular WorkChoices were being modified and toned down as the six-week campaign unfolded. Additionally, the big tax cuts,

the education policies, the policies on the environment – especially on timber giant Gunns’ saw mills in Tasmania – demonstrated a fair amount of what became known as ‘me-tooism’.

Media reports across the board also concentrated on the performance of high-profile Labor environment spokesman Peter Garrett. His well-known background as an conservation activist, agitator and rock star with Midnight Oil placed him at the forefront of Labor’s new team when he was first introduced as a politician and as shadow minister of conservation and environment. His former membership and close association with the Greens Party seemingly assured his genuine credentials and integrity on this front.

During the election campaign, even the conservative Packer magazine The Bulletin[2]Brian Toohey, ‘How Peter Garrett Lost His Voice’, The Bulletin, 15 October 2007. sarcastically reported that Garrett had now ‘lost his voice’. His continuous back flips and policy turnarounds – on issues such as the Gunns/Tasmanian forests and Port Phillip Bay dredging disputes – left many Labor supporters with a deep sense of confusion and disappointment.

This was one of the strongest indicators of the Rudd Labor team’s approach to not stray too far away from the Howard Government’s positions. Most media reports rightly pointed out this cautious, conservative and unashamedly pragmatic approach from Labor. It further strengthened the view that this election campaign was descending to a contest between Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

For some on the left of the political spectrum, observing Kevin Rudd proudly announce that he was a ‘conservative’ on all economic issues pointed to a disturbing vision of a younger and more energetic version of John Howard. The campaign descended to one where both leaders were claiming to be more economically conservative than the other. Rudd was also robust when announcing his ongoing loyalty to the American alliance, arguing that Australia would maintain and maybe even increase its military commitment to the war in Afghanistan. At the same time, Rudd made some references about possible Australian troop reductions in Iraq without being too specific on the details.

There were times where political commentators and media reports across the board were agreeing with Howard’s assessment that ‘Kevin 07’ seemed to be adapting many Liberal Party initiatives. The more cynically minded of those reports concluded that this imitation was indeed the most sincere form of flattery. The ultra-cautious, low-risk approach of the Rudd campaign seemed to be based on highly pragmatic rather than traditional ideological Labor standpoints. Media reports across the board about this were frequent, implying that there wasn’t a huge effective difference between Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

The media could legitimately argue that anything that happened after the 2007 federal election was basically going to be business as usual as far as most issues were concerned. If, for all intents and purposes, there was not much difference between the parties’ policies, perhaps there wasn’t much point in endorsing one party with vigour while condemning the other.

The sound of silence

It became evident early on that the Murdoch newspapers, which included most of the capital city tabloids as well as the national broadsheet, The Australian, were opting for a return of the Howard Government. Major stories and opinion pieces by prominent News Corporation writers such as Andrew Bolt, Terry McCrann, Greg Sheridan and Paul Kelly were certainly not pushing for a change of government. Editorial pieces leading up to the election were similarly predisposed to the Howard Government.

This was maintained throughout the campaign and the only real surprise occurred in The Australian on the Friday before the election. Somewhat out of left field, the all-important and highly anticipated editorial cautiously urged readers to vote for the ALP and Kevin Rudd. On the same day the Herald Sun was firm in its editorial that the sensible voter would surely have to vote for a return of a deserving Howard Government.

For two Murdoch publications, this was surprising but not entirely unprecedented. In 1993, The Australian had urged its readers to vote for Labor’s Paul Keating, while on the same day its tabloid stable-mate the Herald Sun urged readers to vote for Liberal Party leader John Hewson.

Murdoch publicly stated somewhat coyly during the 2007 Australian election campaign that he was ‘staying out’ of the battle and would not direct his editors to vigorously campaign for one side or the other. Murdoch’s decision could have been made for either of the following reasons. Firstly, the two major parties were sufficiently in agreement on most issues so it really didn’t matter who won. Secondly, Murdoch may well have decided to sit this particular Australian election out. This could in part have been due to recent publicity concerning the history of his political involvement and active campaigning on behalf of individual candidates and parties across three continents. The most recent example of this was the open hostility and strike action taken when Murdoch took over the prestigious Wall Street Journal in 2007. He may be one of the last of a dying breed of traditional media moguls, but for those working within the industry the feeling is that he certainly can still pack a lethal punch when he feels so inclined.

Meanwhile, in the Fairfax press there was a somewhat surprising outcome when it came to the final day before the election. The Age, which had generally been publishing pro-Rudd views in editorials and opinion pieces by regular columnists like Michelle Grattan, Tony Wright, Tim Colebatch, Leslie Cannold, Catherine Deveny and guest columnists like Robert Manne, took the unusual step of deliberately not endorsing any party. On the same day, The Sydney Morning Herald firmly opted for Kevin Rudd while the Australian Financial Review endorsed a return of the Howard Government.

What can we make of this? What goes on in media conglomerates when opposing political opinions are expressed? Is there indeed a case to be made by those who argue that not all newspapers owned by the same magnate necessarily speaks with the one voice? Is it true that individual editors of Murdoch’s dailies were able to freely decide to endorse whichever party or leader they genuinely believed would lead the nation more competently? Apologists for the current state of ownership and control of the media argue in this way and would like us to think so.

Opposing views within the same media group

It is more constructive to argue against this by stating that the only time there is diversity of mainstream media opinion is where we have the Tweedledum/Tweedledee situation in place. If Paul Keating and Bob Hawke between them were drawing the Labor Party away from traditional left to the centre or right by privatizing major Australian institutions like the Commonwealth Bank, CSIRO and Qantas, deregulating financial institutions and floating the Australian dollar on money exchanges, then surely there wasn’t that much of a difference between the major parties. They had all come around to following a globalized agenda which was well and truly supported by huge media conglomerates.

It could be argued that when there are very important national and international issues at stake where politicians from opposing sides really do disagree, the media moguls have far less patience and tolerance in allowing for diverse opinions. So, for example, when it came to making decisions about whether to support George W. Bush’s plans to invade Iraq and overthrow Saddam Hussein as part of the ‘War Against Terror’, all 175 of Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers editorialized with one approving voice. Readers were firmly advised that we all needed to support Bush’s brave plan to invade Iraq and effect regime change. In the US, Murdoch’s ratings-winning cable Fox News channel (‘for fair and balanced news’) had been leading this charge unashamedly for a number of years.

It could be argued that when there are very important national and international issues at stake where politicians from opposing sides really do disagree, the media moguls have far less patience and tolerance in allowing for diverse opinions.

Another interesting example of this in 2007 was Murdoch’s conversion to climate change after being a ‘climate change sceptic’ for many years. Again readers were about to witness a fairly uniform change in the tone of articles and editorials in his newspapers.

Arguably, when it really matters and there is a clear-cut choice between very different policy outcomes, old media moguls seem to come out fairly consistently with a uniform voice. If it is true of Rupert Murdoch in Australia, Great Britain and the US, it is also true of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy when he was prime minister and owner of huge amounts of diverse Italian media outlets. There was a remarkably similar set of circumstances in Thailand where former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra was at the same time a privileged owner of major Thai media outlets.

It is of course perfectly acceptable for a media boss to express firm views on the editorial content that he or she owns and controls. What becomes more problematic is the situation where these outlets command such a large proportion of the content that is distributed to the public.

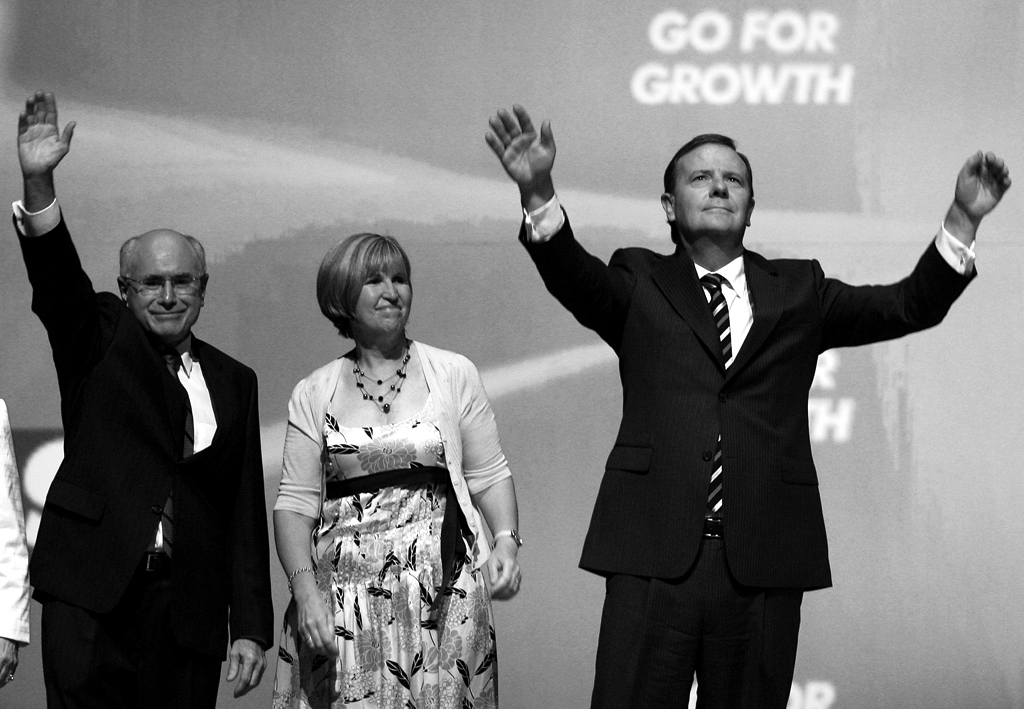

A slippery issue: The Worm in The Great Debate

A highly anticipated event in the 2007 election campaign was ‘The Great Debate’ between the two major party leaders, a debate which is traditionally broadcast live on national television. Other debates are held on television and radio between lesser lights in various ministerial and shadow positions, but nothing is as intensive as the preparation and publicity surrounding the big one. The Great Debate naturally roused speculation on who would win the arguments on substantive policy issues. Yet for many viewers it was also about who would appear more confident and at ease while responding to the pressure of live television and an audience of millions. Live television still seems to provide a forum where what you say becomes almost secondary to how you say it.

The contentious issue which came to dominate most of the pre- and post- debate assessments was The Worm, an electronic line which moved up and down on screen indicating viewer response. Here we had television contributing something unique towards the political process, in the same way that technology has affected the televising (and therefore the playing) of professional sport by gradually replacing umpires and referees.

The Worm, this unique televisual adjunct to the debate, had in fact been used before. Ninety ‘uncommitted’ randomly sampled voters were chosen by the network. These ninety people were then allocated a remote control that they could manipulate in a positive or negative direction upon hearing what either candidate had to say. This instant judgement was then aggregated by computers to create The Worm.

Television is becoming increasingly fond of creating content which allows for the making of instant judgements by audiences. Since the rise and rise of reality television, viewers are constantly encouraged to evict or vote in/out contestants they like/don’t like solely based on the evidence provided to them via edited footage.

There are many problems associated with the making of snap judgements such as these. There is little or no time given for contemplation or weighing up counter arguments that may or may not be given or might have been edited out. We are positioned as instant experts in order to pronounce instantaneous verdicts. On first reflection, this process does seem enabling and interactive as well as democratic. Yet there is something quite superficial, slick, and opaque about this transaction. Every issue and individual is easily reduced and a personalized snap judgement made to affect some outcome.

Liberal Party minders were clear that a condition of the 2007 Great Debate was that there was to be no Worm. This was in fact the way the 2007 televised debate was seen on the ABC. Yet on the higher rating Nine Network, The Worm did in fact appear throughout the debate, despite some last-minute attempts to pull the plug on it.

The net effect of The Worm in the 2007 debate was that is caused much internal bickering between various media and political figureheads. The Worm came out clearly in favour of Rudd. This was not altogether surprising as Howard had clearly lost the corresponding last Great Debate in 2004 against Beazley. Interestingly, this had obviously not adversely affected Howard’s chances in the 2004 election.

Accusations and counter accusations were made by Liberal Party and Nine Network sources. Ray Martin defended his network vigorously while Andrew Bolt of the Herald Sun suggested that Nine was blatantly biased in favour of Rudd and the ALP. If this was all getting out of hand, the important issues to consider were whether The Great Debate had any impact on changing voter intentions or whether it worked to reinforce existing opinions and attitudes.

Surveys of larger groups, and political pundits and commentators generally, agreed that Rudd had performed more creditably on the night. Yet again the electorate was left to speculate on a messy process where the media were central characters in an event which is designed to enhance democracy.

Kev’s Party: election night

The television networks were again going to dominate the election night coverage itself as the counting of votes proceeded. Election night is conventionally understood as an occasion when most who are interested in the election outcome will glue themselves to their television sets. Many baby boomers still speak of the tradition of election night parties – replicating David Williamson’s famous stage play Don’s Party which was based on the 1969 federal election.

Despite the coming of new media, it is still the relatively big and wide television screen which best brings the excitement of watching the live counting of votes. The ABC and commercial networks Seven and Nine had plenty to offer on Saturday 24 November. Naturally there was a difference in the style of coverage between the ABC (hosted by Kerry O’Brien, with Julia Gillard and Nick Minchin as well as the legendary Anthony Green), and Channel Nine (hosted by Ray Martin with Laurie Oakes, Michael Kroeger and Robert Ray). The ABC was offering more traditional and in-depth coverage and analysis of the swings, percentage shifts, seats won and lost, along with forward computer projections. Across the dial, Channel Seven with Sunrise hosts ‘Mel’ and ‘Kochie’ (with Jeff Kennett, Peter Beattie and Joe Hockey) opted for a more light-hearted and entertainment-driven approach. The highlight of that telecast was the look on Jackie Kelly’s face when Jeff Kennett admonished her about the disgraceful phoney pamphlet incident. This was a made-for-television moment.

The actual figures in the ratings race for all networks (the total figure according to OzTam was 2.84 million) were considerably higher than for normal Saturday night viewing. The ABC coverage won the night with an average national viewing audience of 1.12 million. Channel Seven came in next with 967,000 and Channel Nine came in third with 763,000. Channel Ten and SBS also provided more limited coverage during the night. Furthermore, cable station Sky News also had extensive live coverage of the counting of votes.

Election night television coverage is a strange night in the political cycle. In order to achieve balance, networks like to have their sets equally divided between Coalition and Labor representatives as well as allowing for minor party representation whenever this is deemed to be appropriate.

Yet the political point-scoring and argumentative and combative approach that normally applies is – for a few hours at least – often put into the background as political operatives reflect on the performance of their party in what seems a more open and honest way.

For keen observers, these politicians are more humanized than at any other time of the political cycle. Some in-jokes, casual banter and genuinely interesting anecdotal material somehow spill out into the air. At times it is also the case that what is said is not as important or interesting as how it is said. This becomes live human drama which sometimes elevates to melodrama. It again emphasizes that live television provides election night news more effectively than other media forms.

The concession speeches

For many non-government supporters, the concession speech delivered by outgoing prime minister John Howard was something they had been anticipating and salivating about for some time. Many were keen to see a tear or two – a la Malcolm Fraser in 1983 after his defeat at the hands of Bob Hawke. Television does best what other media forms still cannot fully do: get the camera up close and very personal and show ‘live’ that which humanizes the particular moments that help dramatize the intensity of feelings. We are still at the stage with the most advanced technology where big picture screens on television can do this more effectively than mere words in newspapers, on radio or on web sites viewed on computers or mobile phones with poorer quality and much smaller images.

The concession speech was a bit of an anti-climax for any Howard haters who were watching. This was because there were no tears being shed and an apparent sincerity in the claim that ‘I take full responsibility for this defeat’. It also reinforced the long-held and often-begrudging view that Howard – right up until the end – was the ultimate and consummate professional in his performances on national television broadcasts.

As the prime minister elect, Kevin Rudd certainly gave a polished performance in his victory speech. He took the opportunity to again outline the ‘Kevin 07’ broad vision for Australia’s future – and of course for all of ‘Australia’s Working Families’. It was all very predictable and highlighted the fact that these media performances by our political leaders are well prepared and thought through before their delivery.

While there are other aspects of election night on television which deliver more ad-libbed and personalized impromptu statements, this election night delivered a more bland set of responses when it came to the concession/victory speeches. Unfortunately this seems to be part of the bigger picture when it comes to the way political actors choose to perform in set pieces in front of national media outlets.

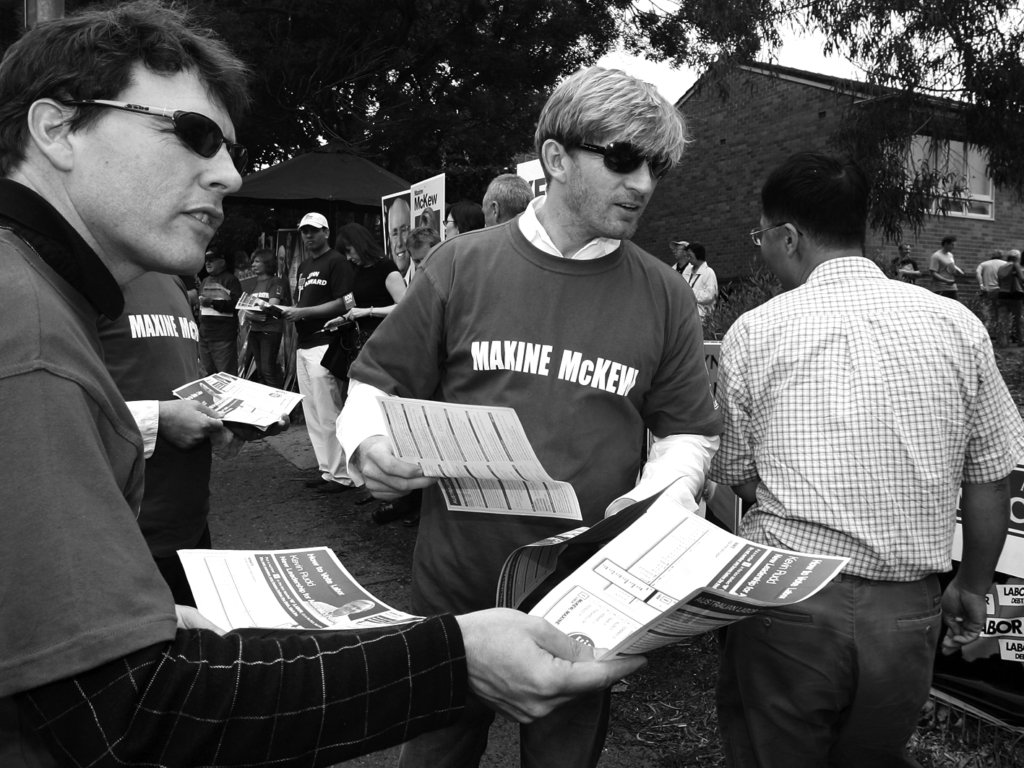

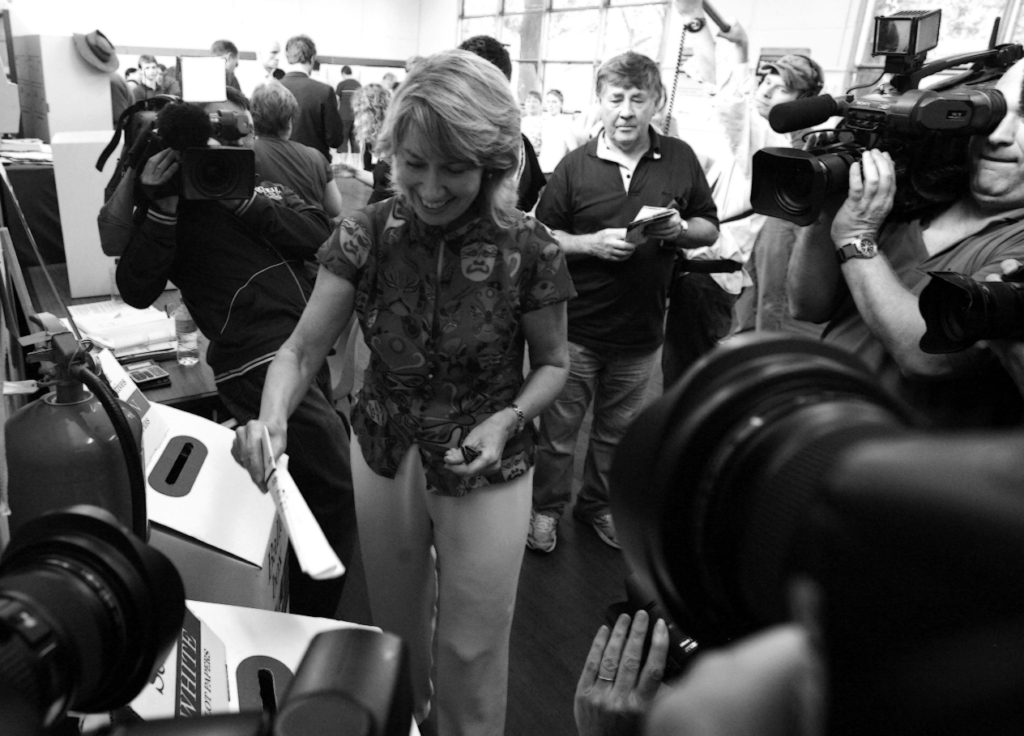

Maxine McKew and Bennelong

For most viewers on the election night coverage, the main event was sometimes overshadowed by the result in one very specific contest in inner Sydney. Saturation media coverage and conjecture, again fanned by innumerable polling, meant that Bennelong was the most discussed and analysed single electorate in the land. There was widespread speculation that it might only be the second time in Australian political history where a sitting prime minister lost his own seat. Many journalists were assigned by media outlets to cover this electorate and one of them, Margot Saville, wrote a book about Maxine McKew’s campaign which was published within days of her victory. On election night her victory looked more and more likely as the evening wore on.

Tellingly, the media assessment of the contest centred around the personality, enthusiasm and energy surrounding former ABC presenter McKew. In a very real sense, this was a case where the media was reporting on one of its own. For some long-time critics, the perceived difficulty for the ABC coverage, anchored by McHugh’s former colleague Kerry O’Brien, was to maintain a semblance of balance. For them (and perhaps even to some others) there was a delightful and embarrassing moment where O’Brien slipped up when announcing that in Bennelong there had been ‘a pronounced swing towards the ABC’.

There is still a great deal in Marshall McLuhan’s 1960 observation about television’s growing effects on the political process. McLuhan was adamant that television was helping make politics resemble a live sports event. Personalities would come to dominate the political narrative as never before – and would indeed become even more important than policies. Anticipation which had been building for the entire year now culminated in personal excitement and disappointment.

It remains true that television (and the media in general) loves conflict, animosity and clear winners and losers who emerge after battle. As mentioned earlier, many have observed that the language of sport has indeed infiltrated the discourse of politics and business – and vice versa.

Maxine McKew was a heroic victor surrounded by euphoric supporters. John Howard’s innings had come to an end. Whichever way the networks and voters felt at the end of the evening, few could ever doubt that it was a great night’s entertainment. No wonder so many had organized those election night parties!

Yet how quickly over December/Christmas and the New Year period did things go back to ‘business as usual’. While some attention was given to late election results as well as some seats still in doubt, the urgency and excitement in the coverage had now well and truly dissipated. In the holiday/silly summer season, the media paid little attention to politics. Meanwhile the television cameras were momentarily focused on new Prime Minister Rudd attending the Boxing Day test match in place of his predecessor, the ‘cricketing tragic’.

Conclusion

For those who followed the saturated media coverage of the 2007 Australian federal election, a number of salient features stood out. As in the past, the media not only reported the campaign – they helped to shape it in a number of ways.

The incessant media-commissioned polls over the past twelve months helped set agendas. They kept politicians, media reporters and journalists, as well as the general public, constantly aware of who was in the lead and who was behind the eight ball. This had the effect of shaping the way both major political parties ran their campaigns.

The 2007 federal election saw a little less political bias or direct media influence than in other recent campaigns. This was most likely due to the Tweedledum/Tweedledee nature of the two major parties as they came to announce similar policies on a number of important issues.

There was a distinctive feeling at the business end of the campaign that it really didn’t matter who won – as both Murdoch and Fairfax groups argued in different publications. The future of the nation wasn’t really at risk and we had two major parties basically heading in the same direction on most domestic and foreign policy issues. The game was really centred around the personalities – and ultimately the question of whether we wanted some change at the top after eleven years of the Howard Government.

It is, of course, true that with the Internet, blogs, digital multi-channelled subscription television and all other forms of new media, we have come a long way since the early 1900s. Those were the days when William Randolph Hearst owned and dominated such a huge proportion of American media outlets (fictionalized so famously in Orson Welles’ classic Citizen Kane [1941]). Lord Beaverbrook similarly held and dominated vast amounts of British media outlets. They both had formidable power to make or break governments and shape the political climate and culture of the day.

Today we need to think seriously about the quality and free flow of information and opinion emanating from media conglomerates, political spin doctors and commissioned pollsters. We also seriously need to sit back and reflect on how far we have actually come.

THE AGENDA-SETTING FUNCTION OF THE MEDIA

Mainstream media provides most of the electorate with news, analysis and opinions about the current state of political play. Citizens generally either read, watch or listen to these themselves, or indirectly come into contact with the general pattern of events by speaking to others – who in turn have accessed media reports. This is the scenario in which media theorists developed the Agenda-Setting Function Theory.

This was a theory that suggested that the media could help shape the debates and arguments about important issues by setting the terms of reference about how they would be discussed. Articulated in the 1960s and 1970s by theorists such as Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams, the theory posited that mainstream media outlets had the ability to help shape the way critical issues were understood – not by telling audiences what to think (as the exponents of the 1920s and 1930s ‘magic bullet’ or ‘hypodermic needle theory’ had done ), but what they could think about.

This theory had plenty of supporters, particularly when the mainstream media were owned and operated by very few dominant media moguls who were able to wield considerable power to shape political agendas. This was the primary reason most governments were concerned about media diversity and tried – with very limited success – to curb the amount of media ownership any individual owner could personally control.

There is plenty of anecdotal and more substantiated evidence to suggest that the personal whims of media magnates have in fact helped shape election outcomes in the past. The 1972 and 1975 campaigns have, for example, been well documented. The Murdoch newspaper stable had an important role to play in first helping Whitlam come to power by being enthusiastic about his campaign and even contributing funds for it. Soon after this, however, Murdoch became completely disenchanted with the Whitlam Government and worked vehemently against him through negative editorials, opinion pieces and even in slanted news stories. These all undoubtedly helped contribute to Whitlam’s defeat three years later.

Before he became prime minister, Paul Keating openly stated that in his view the Melbourne Herald and Weekly Times Pty Ltd and the Sydney Fairfax groups were consistently anti-Labor in both their reporting of political news as well as in opinion pieces and editorials. In 1993, Keating cut a deal with the now notorious Canadian media proprietor Conrad Black, who was then the largest and most influential stakeholder of the Fairfax newspaper chain. In exchange for ‘reasonable and fair’ coverage of the election campaign that year, Black was promised that future legislation in the next Keating Government would ensure an increase to foreign ownership limits for him.

In another famous example, just prior to the 1996 federal election, Kerry Packer personally anointed John Howard, the then Opposition leader, on his network’s top-rating national program A Current Affair. This became the first election victory for John Howard.

While other well-known and/or respected members in the community are also free to endorse any party or candidate they happen to choose, it is reasonable to conclude that an endorsement carries a lot more weight when it comes from a major media owner.

There is an ongoing concern expressed by latter-day Agenda Setting theorists in the field (such as Noam Chomsky and John Pilger) and populists (like Michael Moore) about media conglomerates helping to shape political outcomes, such as the results of major elections and the elevation of those who assume leadership of major political parties. Rupert Murdoch himself was quite a fan of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and US president Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Murdoch openly supported them in a raft of editorials and with favourable personal comments whenever he was interviewed.

Murdoch also made no secret of his admiration of both US president Bill Clinton and British prime minister Tony Blair. Murdoch has been courted by many political figures who have been known to cancel other pressing engagements in order to have an audience with him over a working breakfast, lunch or dinner. Current US President George W. Bush is the latest beneficiary of this, and the acclaimed documentary Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism (Robert Greenwald, 2004) carefully outlines

the ways in which Murdoch’s cable Fox News station vigorously supports Bush’s political agendas.