“… every day and everywhere, man is stopped by myths, referred by them to this motionless prototype that lives in his place, stifles him in the manner of a huge internal parasite and assigns to his activity the narrow limits within which he is allowed to suffer without upsetting the world: bourgeois pseudo-physics is in the fullest sense a prohibition for man against inventing himself … For the Nature, in which they [men] are locked up under the pretext of being eternalized, is nothing but an Usage. And it is this Usage, however lofty, that they must take in hand and transform.”[1]Gardener, C . and Young, R. (1981) ‘Science on TV: A Critique’. In: Popular Television and Film, BFI/Open University Press, London, 1981: p. 178.

I wonder how many well-meaning people have dozed off while watching a science program on TV? Chances are, if they woke up, they would be met with a talking head, earnestly discussing life in a freshwater pond, or a white coat enumerating the joys of liver transplants. It’s enough to make a grown-up want to switch back to The Young Ones for a really fresh and honest look at life.

Why does science on television enjoy immunity from the same standards of criticism applied to other TV programs? Even the hardest-nosed reviewers prod gingerly at Life On Earth and Beyond 2000, afraid of yanking the tail of a very sacred cow. All we ask of a science program is that it be entertaining and not too demanding (God forbid that science should dare to ask of the viewer the level of involvement required by, say, a Geoffrey Robertson Hypothetical!). Why is this so?

Empiricism and Ephemeral Truths

The word ‘science’ invokes images of disinterested men and (less often) women in white coats decanting test-tubes, fiddling with tiny wafers of scratched silicon, calibrating awesome machines, encoding the world into mathematical formulae, and generally being busy unearthing the secrets of the universe. The myth operating behind these images is that of science as progressive, neutral, utilitarian, empiricist, value-free – transcending the mud-wrestling and toad-racing of everyday life with its aggression, deceit, competition, greed, and folly.

Scientific methodology, based on empiricism, reinforces this picture: certain knowledge is assured by the existence of the self as thinker and observer. Empiricism seeks to restore man to all-knowingness, putting the cogito into the Cartesian sum, and taking the ghost out of the machine. Empiricists would have us believe that objective truth exists autonomously ‘out there’, a fait accompli waiting to be observed and described. Thus language – particularly scientific language – is merely the unmisted mirror with which we transmit or reflect this autonomous body of knowledge.

Reflect … or represent? The deconstructionist Jacques Derrida proposed that science, like all western philosophy, is a discourse linked to the “repressive ideology of reason”, which can be traced back to the classical equation between truth and logic. One of the most important things that Derrida ‘did’ to philosophy was to examine it as writing, and not as pure thought. He exposed the fallacy underlying empiricism that reason can dispense with language and arrive at pure, self-authenticating truth. He proposed that, rather than encoding truth, language actively conceptualizes and constructs it.

Despite Derrida’s argument, we remain romantically fixated on the classical notion of pure thought reached via invisible language. Indeed, empiricism is so deeply entrenched in our way of thinking that we aren’t aware of its pervasiveness. Descartes ultimately enabled NASA to put a man on the moon, but he also triggered a fragmentation in general thinking that led to reductionism in the western mind.

One field of science – modern physics – has left the ’empiricist imperative’ behind. New physics acknowledges that the act of observing is part of, and therefore changes, the system of observer and observed. Thus, a researcher is not an impartial neutral purveyor of ‘the facts’ but a highly-charged mass of ideas, beliefs, prejudices, memories, learning, and ambitions (not to mention grant applications) that screens and selects the world of his direct or extended senses, a world that itself responds to the presence of an observer. Unfortunately for science, physics is alone in its enlightenment. The fields of biology, medicine and social sciences are still dividing and splitting, and trafficking in tyrannical truths.

The Voice of God

How does empiricism influence the way science appears on the box? As I have pointed out, science is concerned with making language invisible in its pursuit of objective truth. This translates onto TV as observational realism – a window on the world.

In most science documentaries, the voice of an omniscient, often invisible, narrator acts as a metaphor of truth and authenticity (the ‘unmisted mirror’); it is also metonymic of the scientific community – neutral, objective, detached, harmonious, and disinterested. His (for it is nearly always mature, patient, moderate, restrained, dignified and male) is the “Voice of God”, the observer on the periphery, organizing the cosmos, and holding imminent chaos at bay. On the part of the viewer, such a voice “… induces deference and organizes consent by eliciting willingness to be the passive recipient of versions of history organized and presented for our edification”.[2]Fiske, J. and Hartley, J. (1978) Reading Television. New Accents Series, Methuen, New York.

David Attenborough (much though I admire the virtuosity of his work) is a well-known example. His two series of natural history documentaries, Life On Earth and The Living Planet, are organised around the central thesis that patterns of existence have clearly defined, causal explanations. He provides a generalized taxonomy of the living outer layer of the ball of mud on which we live, a taxonomy that is absolute – no further correspondence will be entered into. Not only does his voice induce deference – it is the very soul of nineteenth century naturalism – but all grey areas are made black or white by the programs’ narrative system of closure.

Biological theories, however sound they may appear, have a history of fallibility; scientists construct models-of-best-fit to accommodate existing empirical data. Sooner or later, these models are replaced slowly or knocked down by new ones. Gradual evolution by natural selection is the model that Darwin proposed last century to explain the patterns and diversity of life. But it has shortcomings, and over the last few years its ascendence has been challenged by other ideas. Life On Earth nevertheless selects for us a body of evidence (and a single point of view) that testifies to the integrity of the classic model of evolution by natural selection. No ambiguity or uncertainty is allowed to crack the flawless edifice.

Like the voice, the camera in this series is all-pervasive, re-presenting the real world on the screen. The narration – the story of living things, selected, modified, or disposed of by the ruthless hand of Mother Nature – provides a structure into which appropriate pictures fit. The images are ordered naturalistically; thus, a close-up shot of ants filmed in a studio will be portrayed as an event observed in the wild.

It’s all a version of empiricism: the message underlying this observational, naturalistic style is that we cannot go beyond the surface appearance of things. Here is the world as it is – without ambiguity, without paradox, purveyed with value-free objectivity. All human fingerprints are carefully wiped away.

Science and Goanna-Oil Salesmen

Television, like science, is a selected, constructed process of representation. But whereas the codes that structure scientific language are literate and logical – the codes of the written word – those that structure the language of TV are visual and verbal. The sense of TV is in pictures and sounds, the sense of science is in symbols (including words) and syntax. As Fiske and Hartley put it

“… television is to some extent subversive of the very values most prized by literacy … the narrative development from cause to effect, universality and abstraction, clarity, and a single tone of voice. Television, on the other hand, is ephemeral, episodic, specific, concrete, and dramatic in mode … and its logic is oral and visual.”[3]R. Barthes, Mythologies, Granada, London, 1972: pp. 155–6.

This subversive, or rather perversive, role is evident in one of television’s highest rating science programs, Beyond 2000. With its well-coiffed reporters, exotic locations, and ad-punctuated segments, the program has all the glamour and restlessness of Sixty Minutes. The presenters use the same pseudo-journalistic style, packaging science (rather than news) as a commodity and as entertainment; their Lois Lane curiosity stops short, however, of querying the methodology and social or historical context of research.

They report to us from what appears to be one of the higher floors of a building in the futuristic city depicted in the opening credit, materializing and dissolving (“Beam me up Scottie”) in a set that vaguely resembles a spaceship. To heighten this sense of unreality, the reporters are filmed through fog filters (the image contrasting absurdly with the sharp focus on close-up shots of hands), shimmering like holographic ambassadors from Tomorrowland. Their context gives them prescience – they look out at us with the wisdom of hindsight, empowered by their position in the future.

If you have trouble distinguishing between the program and intervening ads, don’t panic. Like the rest of commercial television, the program is in the business of selling “bums on seats” to advertisers. But here, the sponsorship relationship (life insurance, personal computers, food, etc.) directly influences the form and content of the show.

Beyond 2000 markets the future-world – it sells science without responsibility, a techno-cargo cult. It displays a Utopia that could only be peopled by the well-heeled: gadgets and gizmos that will make our increased leisure time more fun; expensive medical technology that will be available to a tiny percentage of the world’s population (at the cost of more urgently needed help for the rest).

Each program segment is tantalizingly brief, a technological fix – no time for reflection or questions, it’s off to Japan to see the latest in Space Invader technology. As with all texts, ideological meanings operate at a latent level; they don’t have to be apprehended by the viewer to be assimilated. By celebrating the unstated, unassumed values of our materialist society, Beyond 2000 educates its audience in the myth of science as utilitarian, positivist, and as master of Nature. Behind the breathless pace, we read the message “Progress is inevitable: keep up or drop out”.

This attitude can be summed up as social Darwinism – survival of the fiscal in a blood-stained ‘market-place’. Thus a video games report proclaimed that “… the extremely competitive video game world demands the highest standards of electronic engineering sophistication” in “… a market in which scores of new games emerge every year and only the best survive”. Well, really – is the need that dramatic? Can we turn around and challenge this oppressor or do we keep fleeing in the face of the inevitable, as this program advocates?

By shifting its locus to a dream-like future, Beyond 2000 absolves itself of the need to address imminent problems presented by the March of Science: computerized fishing reels take precedence over more important issues (such as the fate of humanity being decided by technocrats). But then, the aim of the program is to gratify the worst materialist fantasies of viewers, not make them wonder about the alleged virtue of science and scientists.

In ‘special feature’ programs, we are presented with spectacles that serve only to increase our sense of impotence and deference: how to survive a nuclear war (shouldn’t we be putting our efforts and imagination into insuring that it doesn’t happen?); the wonders of the ocean and how man is conquering it (leaving one with the feeling that pretty soon science will leave no wonders for man to conquer).

There’s no denying that the program is entertainment, another homage to the altar of the McNair-Anderson cult by the high priests of commercial television. But if it is setting the agenda for our future – which appears lo be its aim – it is an irresponsible agenda that demands only a dependent, passive, consumerist response to ‘progress’ on our part.

Bad For Your Health?

The Living Planet and Beyond 2000 are two of the ways the TV industry has found of packaging science. Before finishing this discussion. I would like to briefly mention another genre – the medical.

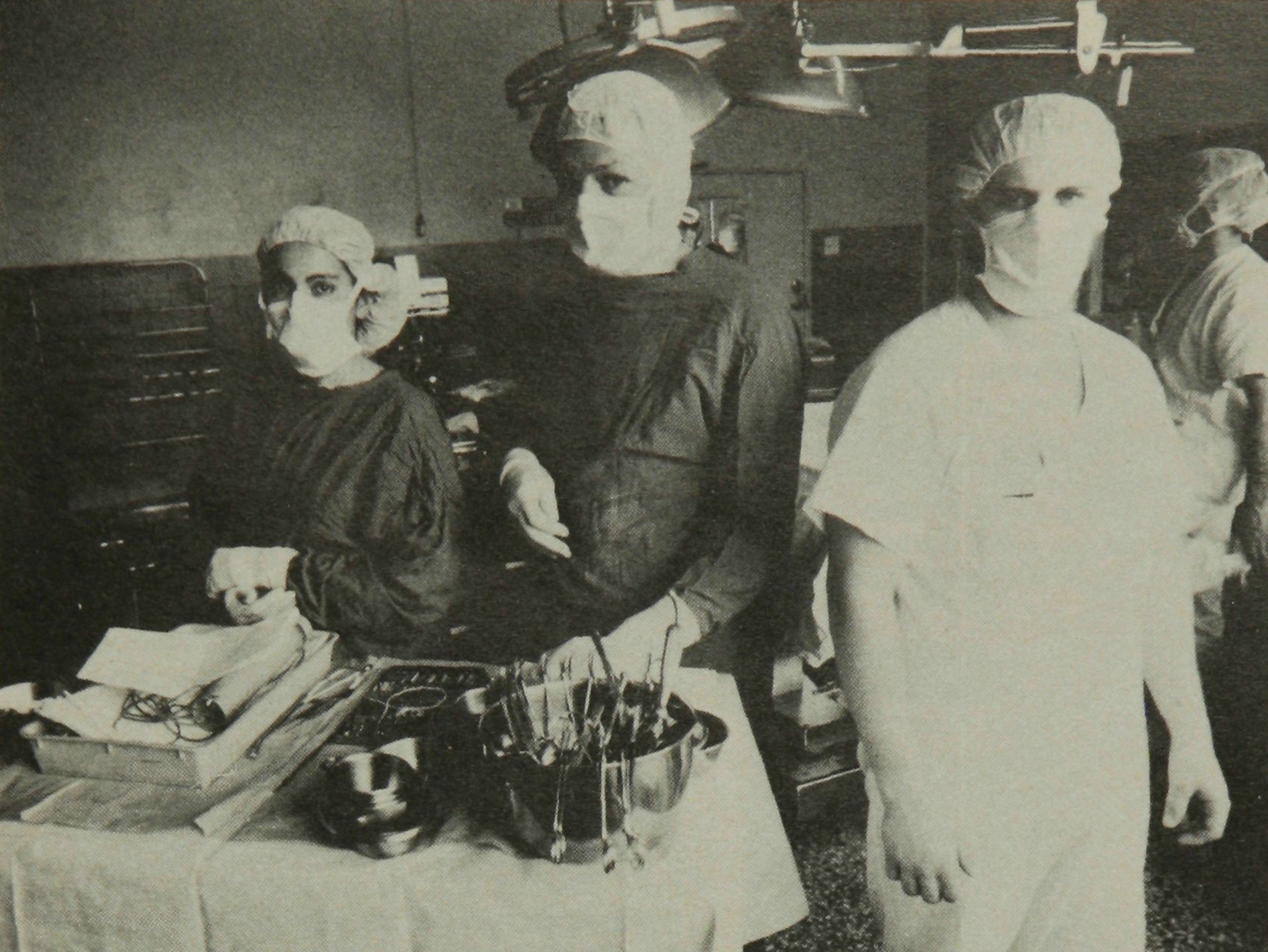

Series and programs dealing with cancer, AIDS, and organ transplants cater to those latent Mr Hydes skulking in many of us – the voyeur and the hypochondriac. (Why else would anyone want to watch bloody operations over their microwaved TV dinner? Perhaps the final joke will be a Dr Duncan’s Video Symptom Show as depicted on that ultimate talking-head series, Max Headroom.)

The mode of address is more dramatic than the other genres: it offers us science as self-revelation, the drama of the human body’s struggle against its environment. It sanctions the idea of medicine’s role as curative, rather than preventive: drugs for all occasions, ad hoc surgery, if-all-else-fails-transplant-somelhing, or bring-in-the-expensive-machine-that-goes-‘bip’. We see a lot of sickness, giving us the impression that illness is a norm. Health, on the other hand, doesn’t bring in the research grants or make for voyeuristic entertainment.

Technology and medicine are changing the way we live, work, play, and reproduce, and for many of us television is a primary source of information about these changes. Yet the current TV representations of science inhibit debate through their patina of empiricism and authority, and their cargo-cult promises. These representations discourage audiences from thinking about the social implications and origins of research (the social and ethical consequences of in vitro fertilization; the narrowing boundary between science and the market-place, dependence on multi-nationals for funding; privacy infringements of new information technology; the role of military spending), and alternative ideologies and viewpoints (energy-efficient lifestyles; systems of medicine founded on health rather than sickness; humanism instead of consumerism).

Is there a light at the end of the tube? Are we all condemned to an eternity of being blinded with science? Perhaps we will have to wait for the advent of guerilla TV, or a laboratory sitcom, or even a Hypothetical on science, with a range of critics from outside disciplines, rather than the usual Big Names trotted out for every public forum on things scientific.

Meanwhile, thank Thatcher for The Young Ones.

Endnotes

| 1 | Gardener, C . and Young, R. (1981) ‘Science on TV: A Critique’. In: Popular Television and Film, BFI/Open University Press, London, 1981: p. 178. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Fiske, J. and Hartley, J. (1978) Reading Television. New Accents Series, Methuen, New York. |

| 3 | R. Barthes, Mythologies, Granada, London, 1972: pp. 155–6. |