Depicting thirteen-year-old girls having sex, consuming alcohol, smoking marijuana and defying adult authorities, Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey’s 1979 novel Puberty Blues[1]Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey, Puberty Blues, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2002. caused a scandal upon its original publication.[2]Australian Story: The Big Chill, ABC Television, broadcast 30 September 2002, transcript online: <http://www.abc.net.au/austory/transcripts/s685468.htm> Accessed 7 July 2003.

For many of the Anglo-Australian girls who reached puberty in the late 1970s or early 1980s, the novel and Bruce Beresford’s 1981 film adaptation coincided with real-life aspirations to engage in the activities depicted therein.[3]Australian girls of Mediterranean or Asian background, by contrast, were less likely to have access to the freedoms depicted in Puberty Blues. More recently, the re-publication of Puberty Blues with two new forewords has imbued Lette and Carey’s depiction of Cronulla ‘surfie chicks’[4]Lette & Carey, p. 1. Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent page references are to this text. with a further historical dimension and positioned it as a potential object of nostalgia. This article uses the novel’s reappearance as a starting point for examining the significance of the Puberty Blues phenomenon, which encompasses both the book and film. A feminist analysis of Puberty Blues is developed here with reference to nostalgic youth films, women’s writing and the female voice.

Revisiting Female Youth

The theme of coming-of-age has been identified with Puberty Blues at various levels. Not only did two teenagers write the novel, but also the film has been linked with Australian cinema’s coming-of-age. In order to address the larger cultural significance of Puberty Blues, this article positions Lette and Carey’s novel and Beresford’s film as two halves of the same phenomenon. This approach reflects the close association that exists between the novel and film, as evidenced in the fact that many of the people who saw the film during its original release did so because of their familiarity with the novel. As Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka have shown, Beresford’s Puberty Blues was released at a time when the Australian film industry was achieving a new maturity. Along with films such as Mad Max 2 (George Miller, 1981) and Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981), Puberty Blues heralded the increasing marketability of film depictions of Australian subjects.[5]Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia Volume 2: Anatomy of a National Cinema, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, p. 151. This was a period in which newly introduced taxation incentives prompted increased investment in the Australian film industry, resulting in turn in a proliferation of market-driven Australian films. As one of the top forty most lucrative Australian films since 1966,[6]See Australian Film Commission, ‘Top Australian films at the Australian box office, 1966 to 31 December 2002’, online: <http://www.afc.gov.au/gtp/mrboxaust.html> Accessed 8 September 2003. The only film centering on teenagers to appear higher in the list is Looking for Alibrandi (Kate Woods, 2000). Puberty Blues is, moreover, the most prominent in a cycle of Australian youth films that emerged in the late 1970s and depicts subcultural themes, a cycle that also includes The FJ Holden (Michael Thornhill, 1977) and Hard Knocks (Don McLennan, 1980). While thus associated at more than one level with Australian cinema’s coming-of-age, Puberty Blues also offers a nascent feminist perspective of adolescence.

To date, the feminist significance of the Puberty Blues phenomenon has received little attention from feminists. Although the novel and film of Puberty Blues have long been perceived as feminist texts, many of the commentators who express this view do not identify themselves as feminists. For example, a 1979 review by social worker Eva Learner dubs Lette and Carey’s novel ‘a feminist’s book; an analysis of social role conditioning from an early age’.[7]Eva Learner, book review of Puberty Blues, The Age (Melbourne), 7 November 1979; reprinted in The Age, section A2, 27 September 2003, p. 2. Similarly, Jim Schembri’s 1982 review of the film highlights ‘the almost brutal singularity of the girls’ subservient sex-maiden roles’, the way in which ‘the ritual-like pairing of Deb and Bruce outlines the group’s respective sex roles’ and the surfie gang’s ‘repression of the girls’ desires’.[8]Jim Schembri, film review of Puberty Blues, Cinema Papers, issue 36, February 1982, p. 72. A few years later, Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka suggest a feminist reading of the film through noting that the script’s positioning of ‘the girls, however passive, as subjects, and the boys as merely their temporary adornments, of little importance or character’ creates ‘a line of resistance in [this] moral comedy’.[9]Dermody & Jacka, op.cit., p. 173. In Peter Coleman’s 1992 study of Beresford’s work, Puberty Blues is described as ‘the sunniest of his feminist films’.[10]Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, HarperCollins, 1992, p. 112. In addition, Kathy Lette has recently dubbed Puberty Blues ‘a strong feminist tract’ that she believes prompted an increase in Australian girls’ participating in surfing.[11]New Dimensions, ABC Television, Broadcast 10 February 2003, transcript online: <http://www.abc.net.au/dimensions/dimensions_in_time/Transcripts/s780748.htm> Accessed 7 July 2003. Meanwhile, the perception of Beresford’s Puberty Blues as a ‘teen-flick, surfie-style comedy’[12]Ann Gul, ‘Bruce Beresford: Puberty Blues’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Film 1978-1992: A Survey of Theatrical Features, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1993, p. 81. seems to have inhibited sustained appreciation of the film among feminists themselves; indeed, until the 1980s, feminist scholars displayed little interest in ‘low’ genres such as horror, comedy and teen film.[13]See, respectively, Carol J. Clover, Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, BFI, London, 1992; Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995; and Frances Gateward and Murray Pomerance (eds), Sugar, Spice, and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002. The feminist significance of Puberty Blues has traditionally been associated with the novel and film’s appeal to female audiences rather than with feminist scholarship.

Yet the focus on female coming-of-age in the novel and film of Puberty Blues is of considerable significance from a feminist perspective. Lette and Carey’s novel employs a double-layered temporal structure that is characteristic of coming-of-age stories, in which the body of the narrative is often set in the past and recounted by one of the characters.[14]Lesley Speed, ‘Tuesday’s Gone: The Nostalgic Teen Film’, Journal of Popular Film & Television, vol. 26. no. 1, spring 1998, p. 25. In the novel, the character of Debbie narrates her teenage experiences that she and her best friend, Sue, had at the age of thirteen, thus situating the narrative in the early 1970s. This retrospective narrational framework is also evident in the novel’s inclusion of an epilogue that chronicles the subsequent activities of the main characters. Beresford’s film, while omitting the epilogue, replicates the novel’s retrospective framework through employing a first-person female voice-over that comments on the narrative in the past tense. With the re-publication of the novel, this retrospective framework is augmented with a further historical dimension that issues from the inclusion of two new forewords. Respectively attributed to expatriate Australian women – pop singer Kylie Minogue and feminist author and academic Germaine Greer – these forewords imbue the novel’s depiction of coming-of-age with larger significance.

The addition of forewords by women with high cultural profiles creates an enhanced sense of the novel’s historical significance and influence upon its readers. For instance, Minogue’s nostalgic comment that reading Puberty Blues was ‘[a] uniquely Australian experience and a fond memory of my early teenage years’[15]Kylie Minogue, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, p. ix. fuses her pop star identity with her portrayal during the 1980s of the archetypal teenage character of Charlene in the television soap opera Neighbours. In particular, Minogue’s account of reading Puberty Blues at the age of thirteen is invested with a latent sexuality that both prefigures and expands upon her present-day girl/woman public persona:

I had shimmied my way waist-high under the bed with my bare feet over the heating duct. Perfect. I was whisked away into a world of boys, the beach and best friends … Such things were important to know and I was fascinated … Needless to say I was straight on the phone for a ridiculous length of time to my ‘bestie’ as soon as I had finished.[16]Minogue, p. ix.

Superimposing a narrative of her own girlhood over the novel’s content, Minogue’s foreword retrospectively idealizes Puberty Blues as a source of vicarious experience and, by extension, an anticipated maturity. Indeed, many readers and viewers now perceive Puberty Blues as an object of nostalgia, linked to an era in which youth cultures were less laden with designer brands and economic rationalism was not yet a household phrase. Yet, while the depiction of a naïve femininity that craves experience is central to the appeal of Lette and Carey’s novel, I will demonstrate that there also exist tensions between the nostalgic overtones of Minogue’s foreword and Puberty Blues’ depiction of less pleasurable past experiences.

An aversion to nostalgia is suggested in Germaine Greer’s foreword, which positions the novel as central to a survey of the hedonistic activities of successive youth cohorts from the 1970s to the present: ‘Puberty Blues is not only a period piece, nor is its colour merely local. The tribal society into which Debbie and Sue are so painfully and destructively inducted still rules in the dead reaches of suburbia.’[17]Germaine Greer, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, p. xi. Although Greer’s teenage years preceded the 1970s by two decades, her apparent familiarity with the social rituals of younger generations infuses her foreword with an authority that reinforces the novel’s capacity to serve as a social document:

The boredom that so terrified Debbie and Sue has deepened into total inertia and deep silence; in most of the endless streets of Australian suburbia absolutely nothing is happening except behind the closed doors of teenagers’ bedrooms, on the Net and on the phone. Nowadays the location for the weekend’s rave is published on the Net at the last minute; the venue is usually Crown land, so that no one can be busted for allowing drugs to be sold on the premises, and the dealers are there in droves.[18]ibid., p. xii.

While canonizing Puberty Blues for an era in which the social surveillance of youth continues to fuel debate,[19]A recent contribution to this debate is Alissa Quart’s Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers, Random House, London, Sydney, Auckland & Parktown, 2003. Greer’s foreword enhances her existing authority in relation to younger generations. The new edition of Puberty Blues re-exposes and aligns Greer to Generation X, a cohort that is likely to have been central to the novel’s original readership, and which is said to have ‘forgotten’ her.[20]Christine Wallace, Greer: Untamed Shrew, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1997, p. 330. Whereas Minogue positions Puberty Blues as a source of nostalgia, Greer’s foreword to the novel offers a privileged and rather more pessimistic exposition of social realities with which Lette and Carey’s portrait of youth is aligned. The significance of the depiction of the past in Puberty Blues can be elaborated in relation to feminism’s widespread influence.

Indeed, many readers and viewers now perceive Puberty Blues as an object of nostalgia, linked to an era in which youth cultures were less laden with designer brands and economic rationalism was not yet a household phrase.

Germaine Greer’s commentary on Puberty Blues facilitates a sustained reading of the novel’s relationship to second wave feminism. Indeed, Puberty Blues was published in an era when feminist texts and other published female perspectives often attracted considerable media attention. Like Greer’s book The Female Eunuch, Lette and Carey’s novel resulted in its authors being positioned as celebrities.[21]Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, HarperCollins, London, 1993. Pivotal to this celebrity was the book’s use of racy autobiographical material.[22]Australian Story: The Big Chill, op. cit., unpaginated. Like Greer, Lette and Carey were also satirical performers, the latter forming a comedy duo called the Salami Sisters who delivered songs offering ‘satirical slices of life’, mainly ‘about the sex war’.[23]Australian Story: The Big Chill, op. cit., unpaginated. Moreover, both Greer and Lette are British-based Australians whose work draws on a rhetorical style that is ‘unmistakably antipodean: forthright, without regard to the authority of entrenched institutions … , and manifesting a biting wit’.[24]Wallace, op. cit., p. 289. Indeed, the writing career that Lette built on the success of Puberty Blues forms part of the increasing international influence of expatriate Australians, of whom Greer remains one of the most prominent examples. The relationship between Puberty Blues and second wave feminism can be further examined in relation to the novel and film’s portrayals of the past.

The depiction in Puberty Blues of coming-of-age can be linked to the film’s association with a particular period in the history of the Australian film industry and also to second wave feminism. In addition, the re-publication of the novel invokes retrospective views of female youth that augment the story’s original temporal framework. The feminist significance of the depiction of the past in Puberty Blues can be identified with the film’s ambivalent relationship to youth films that centre on male characters.

Female Coming-of-age and Surfie Culture

Puberty Blues contrasts with a contemporaneous cycle of nostalgic youth films that centre on male characters. Commentators on Beresford’s film have noted that scenes depicting heroin abuse, gang rape and teenage pregnancy imbue the film with a bleakness that undercuts its ostensible mood of light comedy.[25]See, for instance, Coleman, op. cit. p. 112; Gul, op. cit. p. 81; and Schembri, op. cit. p. 73. This bleakness is also evident in the novel’s epilogue, which reveals that several characters subsequently develop drug habits and/or die. In this way, Puberty Blues eschews the idealization of the past that characterizes nostalgic coming-of-age films such as The Year My Voice Broke (John Duigan, 1987) and Stand By Me (Rob Reiner, 1986), both of which centre upon male characters. Indeed, the nostalgic idealization of the past has been identified most strongly with male perspectives. For instance, Janice Doane and Devon Hodges argue that nostalgic tendencies in literature and theory often work against feminist values through seeking to reinstate ‘natural, fixed sexual difference’.[26]Janice Doane and Devon Hodges, Nostalgia and Sexual Difference: The Resistance to Contemporary Feminism, Methuen, New York & London, 1987, p. 7. Nostalgic writers are thus engaged in a ‘rhetorical practice’[27]Doane & Hodges, ibid., p. 3. that constructs ‘the past [as] a product of their own textual strategies’.[28]Doane & Hodges, ibid., p. 8. Similarly, The Year My Voice Broke invests in traditional gender roles through privileging the writerly voice-over of the character of Danny, who tends to idealize events that took place during his youth in the 1960s.[29]Speed, op.cit., pp. 25-26. Puberty Blues, by contrast, eschews the coming-of-age story’s tendency to idealize the past.

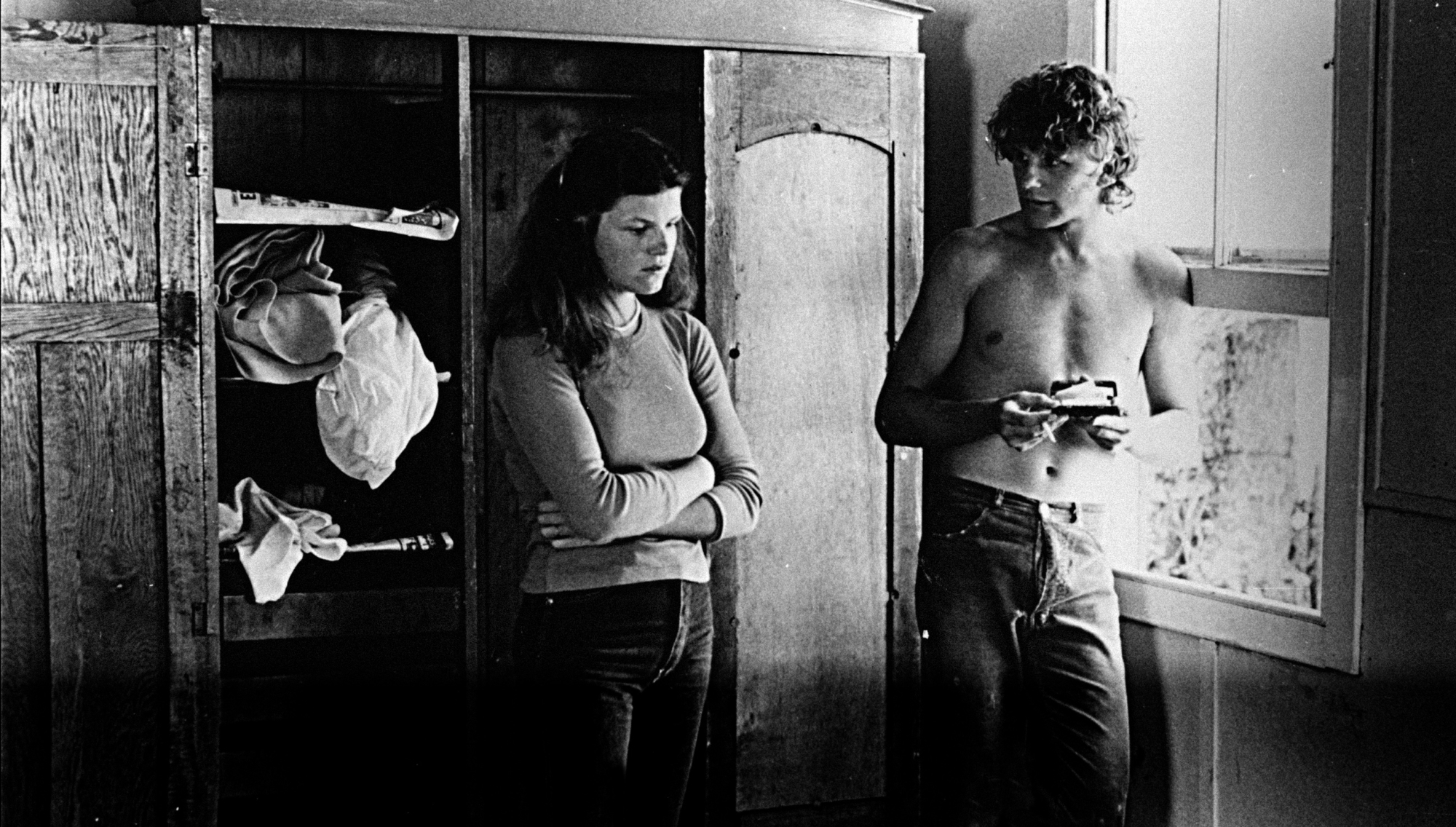

Puberty Blues depicts life in the Australian surf culture of the early 1970s as being frequently less than fulfilling for girls. Debbie’s (Nell Schofield) first sexual encounters, for instance, are presented as being banal and perfunctory. The film conveys the limited scope of her relationship with her boyfriend, Bruce (Jay Hackett), through visually creating a sense of spatial and psychological discomfort. In a scene in which Debbie and Bruce attempt to have sex in the back of his panel van, for example, their lack of meaningful interaction is emphasized through a series of shots in which the characters are respectively positioned at the left and right extremes of the widescreen frame. The sense of spatial confinement is reinforced through the visually flattening effect of the panel van’s dark purple interior, and accentuated when Bruce accidentally hits his head on the vehicle’s ceiling. An ambivalent association between humour and pain is evident in the film’s juxtapositioning of such moments of slapstick with the narrator’s refusal to idealize the relationship: ‘[T]hat was the courting ceremony in Sylvania Heights, where I grew up. But at least I was doing something on Saturday nights.’ Similarly, a later sequence in which Bruce and Debbie attempt to have sex at a party conveys the vacuity of the experience through employing a low level tracking shot that frames the empty space below the bed. The film’s depiction of Debbie’s unsatisfying sexual experiences reveals an ambivalent view of the past.

In Puberty Blues the surfing subculture serves as a post-countercultural locus for hedonistic behaviour among suburban, middle-class male youth. Whereas boys in the subculture seem to benefit from surfing’s traditional association with ‘hedonism, individualism and a transgressive and sexually unruly masculine spectacle’,[30]Jeff Lewis, ‘In Search of the Postmodern Surfer: Territory, Terror and Masculinity’, Sport, Culture & Society, vol. 3, 2003, p. 64. the novel reveals that girls’ activities are limited to the roles of ‘top chick’ (p. 8), ‘moll’ (p. 5) and ‘dickhead’ (p. 2). Within this context, the surfie gang of which Debbie and Sue become members is a local, apolitical extension of the male-dominated youth counterculture in which Greer participated as a groupie during the late 1960s. Just as tensions existed between second wave feminism and the music counterculture,[31]Wallace, op.cit., pp. 169-173. in Puberty Blues the surfing subculture is depicted as both attracting the female protagonists and motivating their eventual defiance of its customs.

This paradox, which seems to underpin the tension between nostalgia and the pessimistic view of the past in the novel and film of Puberty Blues, can be linked to feminism’s analysis of the mythology of romantic love. For instance, Greer’s assertion that ‘in search of romance many women would gladly sacrifice their own moral judgement of their champion’[32]Greer, The Female Eunuch, p. 202. is echoed in the following passage from Lette and Carey’s novel:

All our attempts at romance failed miserably and the only time we ever got close to our boyfriends was when they were on top of us panting. It was hopeless from the beginning but we kept trying. We lived for those boys. (p. 69)

Although apolitical, Puberty Blues’ depiction of dissatisfying aspects of the protagonists’ experiences can be understood in relation to feminism.

The publication of Puberty Blues coincides with the emergence of a subgenre that appeared after the late 1960s and which centres upon women’s revelations of their sexual experiences. In her examination of the female sexual ‘confessional novel’, Rosalind Coward explains that this subgenre emerged as a result of changing sexual roles but is not directly linked to feminism.[33]Rosalind Coward, ‘The True Story of How I Became My Own Person’ in Female Desire, Paladin, London, 1985, pp. 179-180. Exemplified by Kate Millett’s Sita and Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room,[34]Kate Millett, Sita, Ballantine, New York, 1979; Marilyn French, The Women’s Room, Sphere, London, 1978. the female sexual confessional novel emphasizes the role of the protagonist’s past sexual experiences in the development of her mature identity. Despite its inclusion of sexual subject matter, however, this subgenre reflects a ‘shift rather than a liberation in the treatment of sexuality’, in which ‘the discourses are directed at making sex explicit rather than denying it’.[35]Coward, op.cit., p. 182. Equally, the abundance of references in Puberty Blues to ‘root[ing]’, ‘screw[ing]’ and the purported dangers of being perceived as a ‘tight-arsed prickteaser’ (p. 23) reflect a liberalization of publishing censorship practices but do not undermine the sexist stereotyping to which the protagonists are subjected by their peers. While the focus of Puberty Blues on adolescents entails a more limited retrospective framework than those of adult confessional novels, the concerns of the latter subgenre are echoed in Lette and Carey’s juxtapositioning of female oppression with the theme of the acquisition of sexual experience.

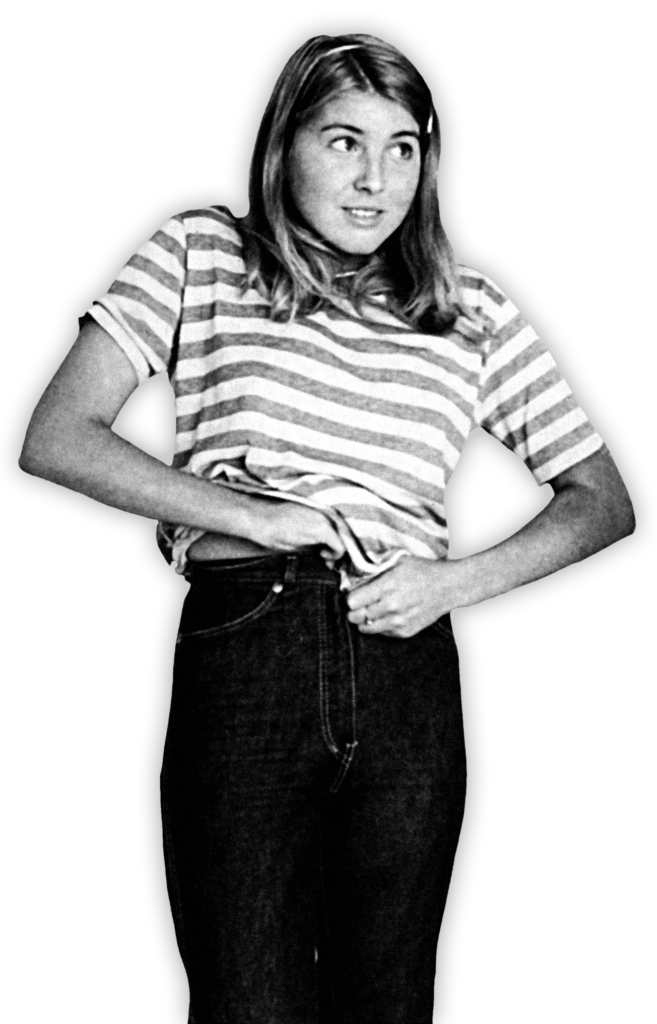

In the surfing subculture of Puberty Blues, the value of female experience is defined in relation to men’s desires and in isolation from feminism. This is a subculture in which girls are permitted neither to eat in front of boys nor to let their eyes stray from watching their boyfriends surf. The misogyny that pervades the world of Puberty Blues is nowhere more evident than in a sequence in the film where the character of Freda (Tina Robinson) is unceremoniously abandoned by three boys after being manipulated into having sex with them.[36]In the novel her name is spelt Frieda, and the girl involved in this incident is another, more peripheral, character. See Lette & Carey, pp. 73-75. In Puberty Blues, girls’ acquisition and display of experience is linked not to their own fulfillment but to acceptance by other gang members, as the novel reveals: ‘To graduate into the [Greenhills] surfie gang you had to be desired by one of the surfie boys, tell off a teacher, do the Scotch drawback and know all about sex’ (p. 7). Juxtaposed with the story’s emphasis on female sexual availability are tensions between girls whose aspirations coincide with the gang’s activities and girls whose aspirations do not.

Female characters are depicted as being actively engaged in the maintenance of conformity of opinion and action within the gang. In the film, for instance, girls use insults to reinforce the gang’s boundaries when Debbie and Sue (Jad Capelja) are bullied on the school bus and when the Greenhills girls vilify Freda, and to reinforce conformity within the gang when Debbie reveals that she is bored with their activities. Just as unseen boys are heard referring to girls as ‘molls’ in some scenes in the film, freedom of female speech and action is usually depicted as serving subcultural rather than individual interests. Whereas Debbie and Sue are frequently positioned as victims of verbal attacks and only occasionally are perpetrators, the film depicts other girls in the gang as repeatedly deriving collective power from rebuking girls within and outside the gang.

Girls’ involvement in verbally reinforcing conformity is particularly evident in the film’s use of off screen dialogue, which can be examined in relation to Kaja Silverman’s equation of the disembodied cinematic voice with diegetic and social power.[37]Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, 1988. In her book The Acoustic Mirror, Silverman argues that the female voice in Hollywood films often ‘coexist[s] with the female body … at the price of its own impoverishment and entrapment’.[38]ibid., p. 141. This constraint is associated with classical cinema’s ‘close identification of the female voice with spectacle and the body’.[39]ibid., p. 39. By contrast, Silverman reveals, feminist cinema has enabled the female voice to ‘pull … away from any fixed locus within the image track, away from the constraints of synchronization’.[40]ibid., p. 141. Beresford’s Puberty Blues, although a market-driven film with origins far removed from independent feminist cinema, employs disembodied female dialogue in depicting how characters exercise influence within the surfing subculture.

The film’s opening sequence, for example, shows Sue and Debbie being subjected to a variety of insults when they attempt to occupy an area of beach frequented by the Greenhills gang, of which they wish to become members. In particular, the protagonists are referred to as ‘brown-nosers’ and ‘little crawlers’. Yet, although the scene highlights the Greenhills girls’ presence on the same beach, the characters from whom the insults originate are not readily identifiable because the slurs occur off screen when the protagonists alone are in shot. The effect in the film of such disembodied verbal attacks is to characterize the Greenhills girls’ behaviour as collective rather than individual. The use of offscreen verbal abuse in Beresford’s Puberty Blues underscores the surfing subculture’s isolation from feminism, depicting girls’ involvement in maintaining subcultural conformity as a source of tension between female characters. Debbie and Sue’s ultimate defiance of the subculture is thus implicitly a response to the conformist attitudes of female as well as male gang members.

The feminist significance of Puberty Blues is evident in the novel and film’s ambivalent depiction of past experiences of girlhood. Despite its apolitical subject matter, Puberty Blues’ depiction of the protagonists’ experiences can be linked to the feminist critique of romance and to female confessional fiction. Yet the isolation of the world of Puberty Blues from feminism is also manifested in the tensions between girls that precipitate Debbie and Sue’s ultimate defiance of the surfing subculture.

Defiance and Social Mobility

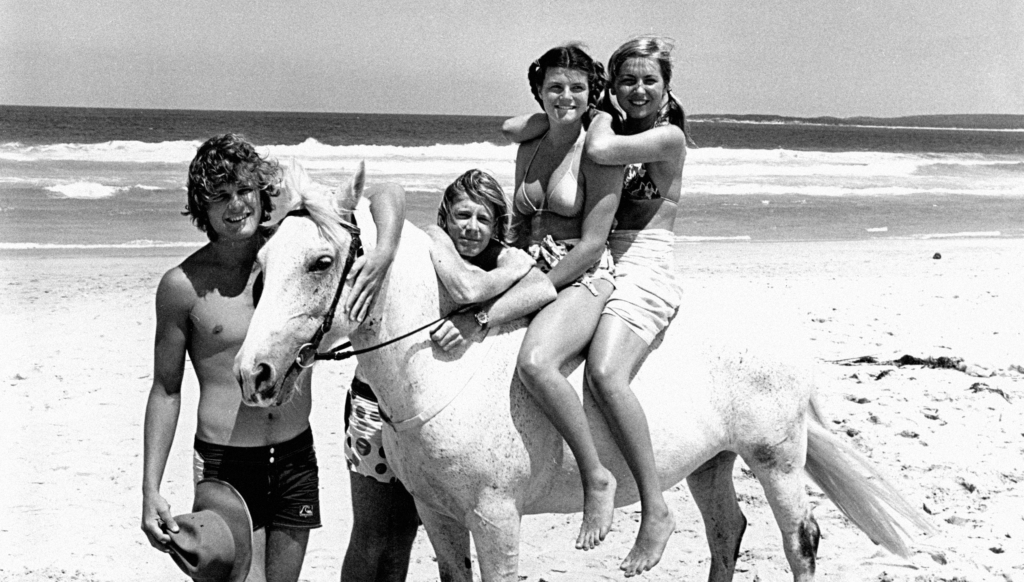

In Puberty Blues the protagonists’ defiance of the surfie gang’s conformism and gendered division of labour echoes Greer’s ‘advocacy of delinquency’ among women.[41]Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, p. 25. Debbie and Sue’s rebellion against the surfing subculture is most spectacularly evident when the protagonists go surfing in the film’s final sequence, thus defying their peers’ prohibition of female participation in the sport. Even today, many female spectators experience a sense of exhilaration when the jeers of onlookers in the film are subdued by Debbie’s display of her surfing ability. In this sequence, the protagonists’ perseverance in the face of verbal slurs – such as ‘Slack-arsed molls!’ and ‘You chicks are bent!’ – is comparable to the forthrightness with which they earlier defied adult authorities by participating in acts of delinquency, such as smoking, underage drinking and cheating in a school examination. Indeed, Debbie and Sue’s decision to surf can be viewed as an act of delinquency in relation to the gang’s prohibition of female surfing. Yet, unlike cheating on exams and smoking in the school toilets, the protagonists’ attempt at surfing implicitly benefits them through effecting their independence from the gang’s constraints on female behaviour. Their sense of newfound liberty is highlighted in the film’s final shot when Sue laughingly declares, ‘I bet we’re dropped!’ and Debbie responds with: ‘Who cares?’ Far from being an isolated act of defiance, moreover, the climactic surfing scene forms part of a larger emphasis in Puberty Blues on the protagonists’ subcultural mobility.

Debbie and Sue’s ultimate rebellion forms an extension of their earlier traversals of social boundaries. In the novel, for instance, the final surfing sequence is preceded by an episode in which the protagonists go surfing while their boyfriends are away but are deterred by the arrival of some ‘cool’ surfers (pp. 29-31). Equally, the film’s final sequence is prefigured in its opening scene, in which Debbie and Sue seek to transcend their ‘dickhead’ status by joining the elite Greenhills gang. The film’s first and last scenes are linked by the use of tracking shots to highlight Debbie and Sue’s dogged transition along a crowded beach. As the opening scene progresses, the protagonists’ independent spirit becomes evident when they leave the crowds and the camera shifts from a series of frontal positions to trail behind them. In the final sequence, the camera again follows the girls when they emerge from the surfboard shop and make their way along the beach. Here, the class undertones of the Cronulla hierarchy are evident when they are heard being called ‘Westies’, a reference to working-class residents of Sydney’s western suburbs. Yet the final scene also demonstrates the protagonists’ increased resistance to the Greenhills gang when Debbie and Sue pause to greet the maligned character of Freda. In Beresford’s Puberty Blues, the protagonists’ quest to participate in surfing is linked to their capacity to independently pursue goals in the face of subcultural opposition.

The story’s depiction of pressures to conform within the surfing subculture is symptomatic of the barriers facing girls of the 1970s and early 1980s who pursued unorthodox goals. Indeed, Germaine Greer implicitly links the novel’s depiction of female social mobility to Lette and Carey’s own later trajectories:

Debbie and Sue are the only ones among their peers to reject their slavish dependence on the boys and motivate themselves to accomplish something[.] Carey and … Lette don’t tell us how they did it; if we want to motivate our children to follow their example, we cannot leave it to dumb luck.[42]Germaine Greer, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, pp. xii-xiii.

I propose that what enables the protagonists in Puberty Blues to ‘motivate themselves to accomplish something’ is their ability to leave the past behind and to embrace new experiences. The refusal of Puberty Blues to either idealize or forget past events is evident in the endings of the novel and the film, where the protagonists vigorously discard past relationships and embark on new experiences. The novel, for instance, ends with the revelation that Sue and Debbie ‘[r]an away from school and at eighteen wrote this book’ (p. 116). Equally, the final scene of Beresford’s film depicts Debbie and Sue’s participation in surfing as both an extension of and a departure from their involvement in the surfing subculture. Far from yearning for the past, the protagonists utilize their prior acceptance into the culture as a source of knowledge that enables them to attempt to surf. The film thus identifies surfing, as an emblem of risk-taking and exhilaration,[43]John Fiske, ‘Surfalism and Sandiotics: The Beach in Oz Culture’, Australian Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, September 1983, online: <http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/serial/AJCS/1.2/Fiske.html> pp. 138-9. Accessed 31 October 2003. For a theoretical examination of the relationship between feminism and risk-taking in the form of physical stunts, see Mary Russo, ‘Up There, Out There: Aerialism, the Grotesque, and Critical Practice’, in The female grotesque: risk, excess and modernity, Routledge, New York & London, 1995, pp. 17-51. with the defiance of social customs and the embrace of new experiences. Fundamental to the feminist significance of Puberty Blues is an emphasis on past experiences as a basis for embracing the present and future.

With the appearance of a new edition of Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey’s Puberty Blues, both the novel and Beresford’s film have been situated in a larger historical context. Presenting a perspective of youth that exists in tension with the coming-of-age story’s tendency to idealize the past, Puberty Blues aligns the protagonists’ teenage years with a period in which activities such as surfing had not as yet been altered by feminism. Within this context, Debbie and Sue use the surfing subculture as a means of reinventing themselves by becoming members of an elite gang. Yet this experience also prompts their defiance of the surfing subculture’s customs. The protagonists’ ultimate participation in surfing engages impulses encouraged by second wave feminism, forming a prescient and powerfully iconic visual representation of female involvement in traditionally male-dominated water sports.

This article has been refereed.

Endnotes

| 1 | Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey, Puberty Blues, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2002. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Australian Story: The Big Chill, ABC Television, broadcast 30 September 2002, transcript online: <http://www.abc.net.au/austory/transcripts/s685468.htm> Accessed 7 July 2003. |

| 3 | Australian girls of Mediterranean or Asian background, by contrast, were less likely to have access to the freedoms depicted in Puberty Blues. |

| 4 | Lette & Carey, p. 1. Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent page references are to this text. |

| 5 | Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia Volume 2: Anatomy of a National Cinema, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, p. 151. |

| 6 | See Australian Film Commission, ‘Top Australian films at the Australian box office, 1966 to 31 December 2002’, online: <http://www.afc.gov.au/gtp/mrboxaust.html> Accessed 8 September 2003. The only film centering on teenagers to appear higher in the list is Looking for Alibrandi (Kate Woods, 2000). |

| 7 | Eva Learner, book review of Puberty Blues, The Age (Melbourne), 7 November 1979; reprinted in The Age, section A2, 27 September 2003, p. 2. |

| 8 | Jim Schembri, film review of Puberty Blues, Cinema Papers, issue 36, February 1982, p. 72. |

| 9 | Dermody & Jacka, op.cit., p. 173. |

| 10 | Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, HarperCollins, 1992, p. 112. |

| 11 | New Dimensions, ABC Television, Broadcast 10 February 2003, transcript online: <http://www.abc.net.au/dimensions/dimensions_in_time/Transcripts/s780748.htm> Accessed 7 July 2003. |

| 12 | Ann Gul, ‘Bruce Beresford: Puberty Blues’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Film 1978-1992: A Survey of Theatrical Features, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1993, p. 81. |

| 13 | See, respectively, Carol J. Clover, Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, BFI, London, 1992; Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995; and Frances Gateward and Murray Pomerance (eds), Sugar, Spice, and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002. |

| 14 | Lesley Speed, ‘Tuesday’s Gone: The Nostalgic Teen Film’, Journal of Popular Film & Television, vol. 26. no. 1, spring 1998, p. 25. |

| 15 | Kylie Minogue, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, p. ix. |

| 16 | Minogue, p. ix. |

| 17 | Germaine Greer, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, p. xi. |

| 18 | ibid., p. xii. |

| 19 | A recent contribution to this debate is Alissa Quart’s Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers, Random House, London, Sydney, Auckland & Parktown, 2003. |

| 20 | Christine Wallace, Greer: Untamed Shrew, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1997, p. 330. |

| 21 | Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, HarperCollins, London, 1993. |

| 22 | Australian Story: The Big Chill, op. cit., unpaginated. |

| 23 | Australian Story: The Big Chill, op. cit., unpaginated. |

| 24 | Wallace, op. cit., p. 289. |

| 25 | See, for instance, Coleman, op. cit. p. 112; Gul, op. cit. p. 81; and Schembri, op. cit. p. 73. |

| 26 | Janice Doane and Devon Hodges, Nostalgia and Sexual Difference: The Resistance to Contemporary Feminism, Methuen, New York & London, 1987, p. 7. |

| 27 | Doane & Hodges, ibid., p. 3. |

| 28 | Doane & Hodges, ibid., p. 8. |

| 29 | Speed, op.cit., pp. 25-26. |

| 30 | Jeff Lewis, ‘In Search of the Postmodern Surfer: Territory, Terror and Masculinity’, Sport, Culture & Society, vol. 3, 2003, p. 64. |

| 31 | Wallace, op.cit., pp. 169-173. |

| 32 | Greer, The Female Eunuch, p. 202. |

| 33 | Rosalind Coward, ‘The True Story of How I Became My Own Person’ in Female Desire, Paladin, London, 1985, pp. 179-180. |

| 34 | Kate Millett, Sita, Ballantine, New York, 1979; Marilyn French, The Women’s Room, Sphere, London, 1978. |

| 35 | Coward, op.cit., p. 182. |

| 36 | In the novel her name is spelt Frieda, and the girl involved in this incident is another, more peripheral, character. See Lette & Carey, pp. 73-75. |

| 37 | Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema, Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, 1988. |

| 38 | ibid., p. 141. |

| 39 | ibid., p. 39. |

| 40 | ibid., p. 141. |

| 41 | Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, p. 25. |

| 42 | Germaine Greer, ‘Foreword’ in Lette & Carey, pp. xii-xiii. |

| 43 | John Fiske, ‘Surfalism and Sandiotics: The Beach in Oz Culture’, Australian Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, September 1983, online: <http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/serial/AJCS/1.2/Fiske.html> pp. 138-9. Accessed 31 October 2003. For a theoretical examination of the relationship between feminism and risk-taking in the form of physical stunts, see Mary Russo, ‘Up There, Out There: Aerialism, the Grotesque, and Critical Practice’, in The female grotesque: risk, excess and modernity, Routledge, New York & London, 1995, pp. 17-51. |