This article refers to the original Japanese-language releases.

A host of Japanese animators have been feted for the mantle of ‘next Miyazaki’, but Mamoru Hosoda once came close: he was initially commissioned by Studio Ghibli to direct Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyakazi, 2004),[1]See Mark Schilling, ‘Studio Ghibli’s New Film to Be Directed by Rival’, ScreenDaily, 2 September 2001, <http://www.screendaily.com/studio-ghiblis-new-film-to-be-directed-by-rival/406748.article>, accessed 30 May 2017. before withdrawing from the project. Hosoda never helmed a film for Ghibli, but the four features he made after graduating into the realm of anime auteur – The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006), Summer Wars (2009), Wolf Children (2012) and The Boy and the Beast (2015) – have been some of the most artful animated pictures of this century.

Born in 1967 in Kamiichi, Hosoda was, like so many animators, inspired by Miyazaki, after seeing the great master’s debut, The Castle of Cagliostro, on its release in 1979.[2]Carlos Aguilar, ‘The Boy and the Beast Dir. Mamoru Hosoda on Shared Fatherhood & Why His Films Deal with Two Worlds’, Indiewire, 15 January 2016, <http://blogs.indiewire.com/sydneylevine/the-boy-and-the-beast-dir-mamoru-hosoda-on-shared-fatherhood-why-his-films-deal-with-two-worlds-20160115>, accessed 30 May 2017. He started out among Toei Animation’s factory floor of animators, such rigorous conditions instilling in him a strong work ethic. He rose through the ranks by working on anime franchises: Dragon Ball Z, Sailor Moon and Digimon. Hosoda’s first feature-length directorial credit, Digimon: The Movie (2000), wasn’t actually a feature, though: an American studio edited together shorter made-for-TV episodes directed by both Hosoda and Shigeyasu Yamauchi and called it a ‘movie’ for US audiences. His first true feature was One Piece: Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island (2005), the sixth movie in the One Piece pirate-adventure series. Hosoda admitted that his early motivations were just to make ‘films that were really hard-edged, slick and stylish’,[3]Mamoru Hosoda, in the featurette Direction File (A Talk with the Director Mamoru Hosoda), The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, DVD, Madman, 2009. but that changed when he started making his own features.

His four films are fantastical works: The Girl Who Leapt Through Time involves time travel and its attendant conundrums; Summer Wars, a collision between real and virtual realms; Wolf Children is about half-human, half-wolf kids; and The Boy and the Beast is set between modern-day Shibuya and an underworld of anthropomorphised animals. But they’re all imbued with real emotions and relatable situations, their fantastical adventures all, essentially, symbols of the disorienting upheaval of adolescence. Each boasts a young protagonist in a coming-of-age setting; the four alternate between female and male leads, between shōjo and shōnen styles.[4]The term shōjo refers to ‘anime and manga […] aimed at girls between the ages of ten and eighteen’ that ‘tend to focus on romance and interpersonal relationships’, while shōnen is aimed at ‘young boys under the age of fifteen’, ‘have a young male hero’ and ‘are focused on action, adventure, and fighting’; see Richard Eisenbeis, ‘How to Identify the Basic Types of Anime and Manga’, Kotaku, 8 March 2014, <https://www.kotaku.com.au/2014/03/how-to-identify-the-basic-types-of-anime-and-manga/>, accessed 30 May 2017. In making films about young people, Hosoda is speaking to his audience: ‘I want to make movies that reaffirm the future, and let them know that this world is a world worth living in.’[5]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Aguilar, op. cit.

Hosoda’s films are all ensconced within the Japanese concept of seishun, the springtime of youth. Both Summer Wars and The Boy and the Beast span years, showing their protagonists grow from children into young adults. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Summer Wars deal with nascent pubescent feelings of desire, attraction, love. These aren’t, simply, coming-of-age tales, but ones in which Hosoda uses the liminal upheaval of youth as narrative impetus. ‘I think of movies as depicting moments of change,’ Hosoda says. ‘Change is growth, and that change also possesses the same dynamism that movies do. The most shining example of the dynamism of that change is children.’[6]ibid.

While typical narratives of this sort – from The Wizard of Oz to Spirited Away – set a lone youngster on a quest, Hosoda finds the heart, and heartache, in Wolf Children’s growing-up story by shifting perspectives. His great study of childhood is told, unexpectedly, as a shrine to motherhood.

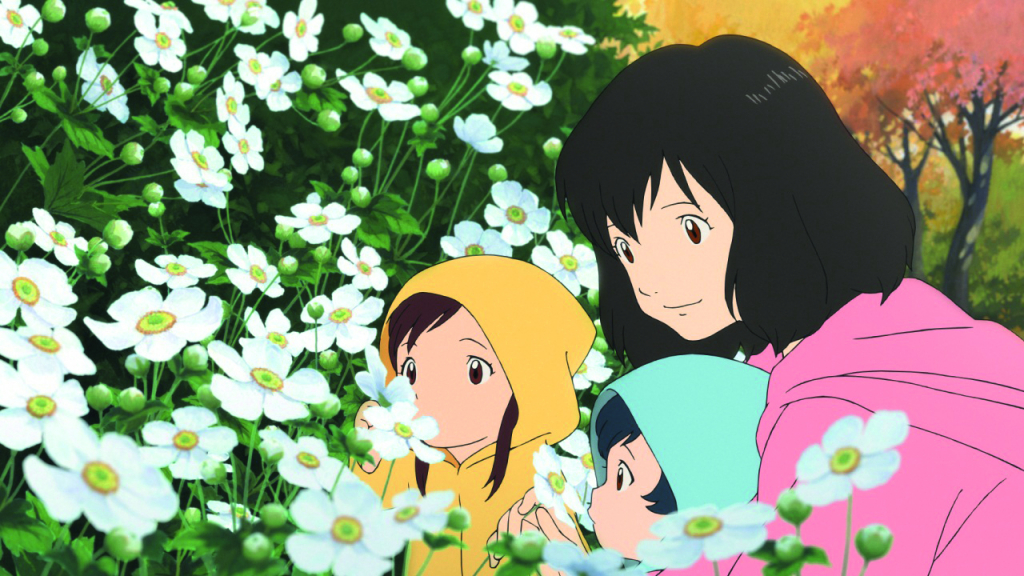

Wolf Children is Hosoda’s great study of childhood, following a brother and sister from birth through to independence. Of course, they’re half-human, half-wolf, the director inspired not just by Japanese folklore and animism (their blood is part Honshū wolf), but by kids stories, in which adults are few and children and animals are peers. As the director explains, ‘before children live in the world of their parents and other people, they must learn the principles, truths, and important things they need to live in the world of animals’.[7]bid. Yet, while typical narratives of this sort – from The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) to Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001) – set a lone youngster on a quest, Hosoda finds the heart, and heartache, in Wolf Children’s growing-up story by shifting perspectives. His great study of childhood is told, unexpectedly, as a shrine to motherhood. ‘I wanted to outline parenthood […] where the relationship starts and where it ends,’ Hosoda has said; ‘the passing of time in this story is stretched out over 13 years. It was necessary to show everything that a parent does for their children.’[8]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Ryan Huff, ‘Interview with Wolf Children Director Mamoru Hosoda’, Madman website, 20 January 2014, <https://www.madman.com.au/news/interview-with-wolf-children-director-mamoru-hosoda/>, accessed 30 May 2017.

Hana (Aoi Miyazaki) is a solitary student living in Tokyo who meets a mysterious, unnamed young man (Takao Ohsawa) – another lonely soul – at a university lecture. At first, they bashfully bond in shared learning: their first date finds them silently reading in the library (this bookish romantic angle later repeated by Hosoda in The Boy and the Beast). Inevitably, their nascent courtship has to hit a moment of revelation: the Wolf Man (as the credits list him) shows her his true, furry colours. As wolf, he’s still a handsome specimen, with the floppy fringe of a J-pop idol and shining blue eyes. He’s attractive enough that they get fresh when he’s still in wolf form – bestiality has never seemed so sweet! – and, via a nimble passing-of-time montage, we see the pair settling into domesticity, self-sufficiency and homebirth. First comes a girl, Yuki, and then a boy, Ame;[9]Yuki is voiced as a child by Momoka Ohno and as a teenager by Haru Kuroki, while Ame, by Amon Kabe and Yukito Nishii. the former, born on a snowy day, and the latter, a rainy one. The arrival of children stirs paternal instincts and, upon Ame’s birth, tragedy strikes, as their wolf father, out hunting to provide for his new cub, is killed. The tragedy is made genuinely tragic by the bleak, unexceptional way Hosoda depicts it: Hana, worried, heads out into the rainstorm with young children strapped to her back and front, and ends up seeing the father of her children, still in wolf form, dead in a drainage ditch, being bagged up by sanitation officers.

Just like that, Hana is made a single mother, thereby amplifying her maternal sacrifice. Raising a pair of wolf children in a Tokyo apartment soon proves impossible: the kids (boisterous Yuki, reticent Ame) equal parts wild toddlers and naughty puppies, child-protection case workers wondering why the children have never had check-ups or vaccinations, Hana unsure of whether to take her sick kids to a paediatrician or veterinarian. The answer is to move to the middle of nowhere: an old, dilapidated, Totoro-esque[10]My Neighbor Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988). house miles from neighbours, on the edge of a wild forest, where the rent, in the words of the area’s lone real estate agent, is ‘practically free’. Here, the kids are free to transform into wolves (when they change, their pants magically disappear, but their scarves or jumpers are left preppily tied around their lupine necks) to engage with their animal instincts in the wild. Their Otherness makes for ready parable – at one point, Ame weeps of storybooks, ‘Why is the wolf always the bad guy? Everyone hates them, and they’re always killed in the end’ – but the children are never persecuted, nor discovered. They’re taught to keep their wolfiness a family secret (spelt out, beautifully, in pencil drawings done by Hana), something they struggle to do when angry.

The threat of discovery becomes amplified when the kids go off to school, and Yuki, as adolescent, earns the male attentions of rebellious Sohei (Takuma Hiraoka). Here, Hosoda plays out normal parental anxieties in a mystical tale: as Yuki and Ame grow increasingly independent, their mother must slowly let them go, with a mixture of melancholy, pride and pain. Yuki, once the boisterous pup who had to learn ‘no other girls played with rat snakes for fun’, yearns to be more and more human, finding their out-of-the-way house too far from friends, society, culture. Ame, once shy and timid, spends more and more time as a wolf, learning the ways of the wild from his ‘sensei’, a wise old fox. He, in contrast to his sister, never wants to leave the forest, chooses to be animal over human. During a climactic storm (a Miyazaki-ish touch), we feel a mother’s role washed away – she no longer protector, no longer needed. There’s a real sense of loss as Hana must learn to let go, sending her kids off into the world with the hopes that they’ll live lives worthy, true. ‘Looking back on the twelve years she spent raising us,’ Yuki says, in voiceover, ‘Mother smiled, saying that it was over in a moment, like a fairytale.’

Hosoda employs an old-fashioned tool of animation – the reuse of backgrounds to save labour hours – as an artistic, cinematic device, the repetition of scenes, locations and compositions a way of showing different moments as being the same instant in time. Or, in contrast, heightening the passage of it.

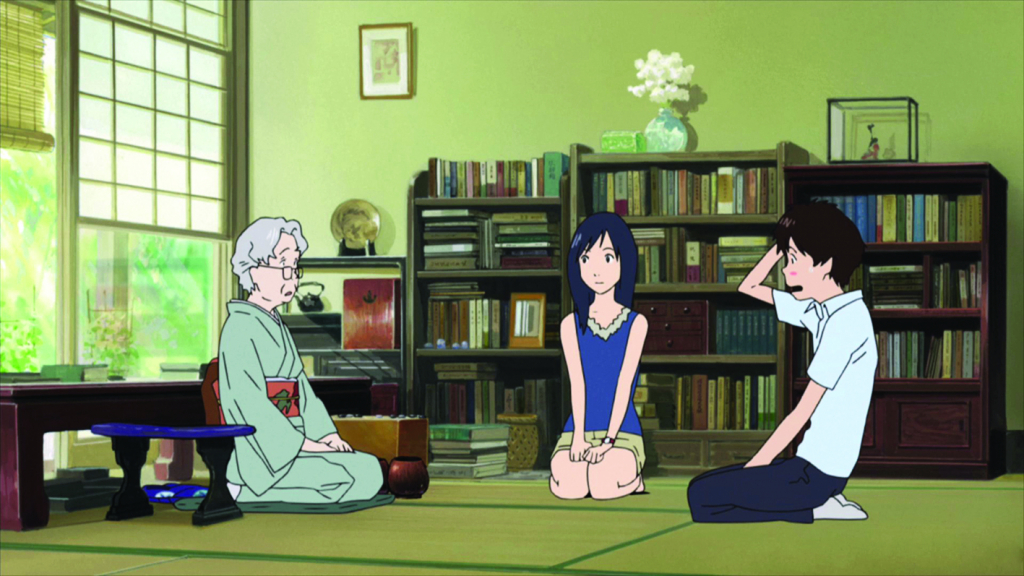

Hosoda followed up Wolf Children’s portrait of motherhood with a film essentially about fatherhood – or, at least, a young boy’s desire for alpha-male role models. The Boy and the Beast is set, largely, in an underworld of yōkai, anthropomorphised animals that live by a code steeped in martial-arts notions of honour, sacrifice. Here – as intoned by an opening fanfare that sets up the narrative as a story within a story – the lord of the realm is about to ascend into godhood, and needs to anoint his successor. Iozen (Kazuhiro Yamaji), a magnanimous warthog with a leonine mane, seems like a natural choice, whereas the bear-like Kumatetsu (Kōji Yakusho) – brash, arrogant, obnoxious – doesn’t even have a pupil to his name. Enter Ren (Aoi Miyazaki / Shōta Sometani), an orphaned, angry runaway from the teeming streets of Shibuya, who finds his way into the animal underworld of Jutengai, which exists as a hidden mirror-world to Tokyo. They make a natural pair – a master needing a student; a boy, a father figure – their constant bickering coming from their hard-headed similarity. Over time, each learns from the other: Ren how to fight; Kumatetsu, to find equanimity while sparring; both, to crack open their hyper-masculine facades and let love in. While there’s monastic devotion and Eastern mysticism familiar from samurai flicks, The Boy and the Beast feels just as much like a sports movie: a cantankerous coach and a misfit pupil bonding together to find unlikely success.

Outside of this masculine world of ritualised fights – equal parts kendo sparring and buck-like butting of alpha-male heads – an adolescent Ren slips away, back to the Tokyo he abandoned as a child. There, he spends time in libraries with love-interest Kaede (Suzu Hirose), ravenous for all the schooling, all the knowledge, that he’s missed out on. This manifests in a desire to be a ‘normal person doing normal things’, and a yearning to return to the human world. There, he seeks out the absent father who was pushed out of his life in childhood, but those who raised him – Kumatetsu, monastic pig Hyakushūbō (Lily Franky) and wry monkey Tatara (Yō Ōizumi) – who actually showed up every day, rain or shine, are the biggest influence on our hero, Hosoda lionising the quotidian simplicities of parental sacrifice.

The film’s fantasy world is a place where humans can deal with their problems through conquering symbolic fights, but, inevitably, there’s bleed between the two. And so the climactic show-stopper is a wild fight between Ren and a rival human, Ichirōhiko (Haru Kuroki / Mamoru Miyano), who was Iozen’s pupil, and who also straddles – and moves between – the realms of man and yōkai. The showdown happens back in Shibuya, and is a sequence of unrestrained animated ambition, on the scale of a superhero movie. Ichirōhiko becomes a monstrous black whale rippling with electricity, swimming underneath city streets, exploding out of the ground in showers of luminous raindrops. Cars and trucks are sent flying, mass destruction is on a disaster-movie scale, and Tokyo’s downtown skyline shakes.

It’s reminiscent of Summer Wars, another film filled with wild visual ambition, dual realms and a ‘fate of the world’–worthy climax. Hosoda was inspired to write it after seeing his wife’s growing obsession with online gaming; to him, that symbolised a shift away from human interactions and the traditional, and towards digital realms and modern values. He folded that into a ‘meet the family’ story that was inspired, too, by his marriage, and meeting his new in-laws: ‘All these people who were total strangers before, were suddenly my family,’ Hosoda says. ‘Your family suddenly doubles in size […] I wanted to put that into a film.’[11]Mamoru Hosoda, in the featurette Interview with Mamoru Hosoda, Summer Wars, DVD, Madman, 2011.

In Summer Wars, Kenji (Ryunosuke Kamiki) is a high-school maths whiz who spends his spare time participating in – and serving as moderator of – the virtual-reality realm OZ, a Sgt. Pepper’s–esque psychedelic fantasia filled with its players’ cutesy avatars. It’s an internet platform becoming enfolded with the Internet of Things: not a total escape from reality, but an online realm in which banal tasks – like banking or paying bills – can be performed in videogame guise. With government organisations, utilities companies, banks and brands all horning in on OZ – and with people’s personal information entirely integrated within – it’s a white whale for hackers; soon enough, flaws are exploited, identities seized, security compromised, society thrown into chaos. At the same time that this calamity befalls Japan, Kenji is far from home. He’s been recruited by his school’s cutest, most popular girl, Natsuki (Nanami Sakuraba), to pose as her boyfriend – yes, that old sitcom ruse! – at her grandmother’s ninetieth birthday party in the countryside. And so, like Hosoda himself, Kenji meets a whole host of in-laws, the film thirty characters deep, its zany family members so vast that the impossibility of remembering them all is turned into a joke. The whole clan – young and old, male and female, loud and shy, black sheep and matriarch – must band together to combat those waging war on society, be it via favour-wrangling, game-playing or grit. Hosoda evokes samurai tradition and familial honour, and employs the tropes of action movies: military hardware, dramatic hacking, the threat of nuclear explosion, a ticking-clock countdown. Here, the antidote to the individualism of the online realm, and the egomania of trolling, is the collective power of community and family.

Whereas Summer Wars is ‘about the vitality of a Japanese rural family’, Hosoda offers that ‘The Girl Who Leapt Through Time [is] about the vitality of a teenage girl’.[12]ibid. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s 1967 novel of the same name has been adapted countless times over the years – for TV and feature film, live action and animation, even turned into a song – but Hosoda uses this famous source text as a springboard, his true debut feature having an in-built brand name on its side, but exploring ideas and animation styles that’ve become his trademark. His The Girl Who Leapt Through Time makes the protagonist of the original story an eccentric aunt, ceding the narrative to a modern-day niece, Makoto (Riisa Naka), whose high-school days are winding up, with summer – and its chirping cicadas, sweaty nights and baseball games – in the air. Her best friends are two sporty dudes: the devoted doctor-in-waiting Kōsuke (Mitsutaka Itakura) and the mysterious, rebellious transfer student Chiaki (Takuya Ishida). There’s a love triangle, of sorts, lurking there; much of the drama in The Girl Who Leapt Through Time comes with heaving teen emotions, high-school social strata, and the inability to own up to fond feelings for the ‘wrong’ paramour.

Anchored in the recognisably domestic and adolescent, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time’s heady exploration of time travel – or, as it poses them, ‘time leaps’ – always feels like a product of emotions. Makoto discovers her ability to move through time while averting tragedy: after crashing her bike through a level-crossing barrier in front of an oncoming train, she loops back to mere minutes before. Soon, she learns to control her jumps in time and, being a teenager, puts it to her advantage: bending time to ace tests, eat her favourite meals, get extra karaoke-booth sessions, thrash the boys at baseball. Hosoda animates the wormholes she moves through with familiar visual devices: liquid clocks, surrealist imagery, scurrying digital numbers, paisley mandalas, a psychedelic wash of water – all suspended in black nothingness. Leaping about is a total lark, but, when her aunt cautions that ‘maybe there’s someone out there having a rough time because of your good times’, the dark side of time travel soon comes up: the butterfly effect of tampering with events leads to classic ripples of divergent fate, others suffering as Makoto succeeds. As her number of ‘allowed’ skips counts down, she has to try and fix what she’s fucked up. Makoto does the same things over and over, but also does the same things as her aunt – history forever repeating, the film beginning and ending at the same moment on a baseball pitch, the narrative a möbius strip, time a flat circle.

Hosoda employs an old-fashioned tool of animation – the reuse of backgrounds to save labour hours – as an artistic, cinematic device, the repetition of scenes, locations and compositions a way of showing different moments as being the same instant in time. Or, in contrast, heightening the passage of it. In The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, Makoto moves repetitively through the same exact frames as she plays out time, over and over – first ‘mastering’ her new skill, then desperately trying, and often failing, to put things right. But, in Wolf Children, Hosoda shows the changing of seasons – and the progression of romance – by having his budding paramours returning to the same places, the same routines, at different times. Charting, as it does, roughly fifteen years, Wolf Children needs to find creative ways to move through time, and Hosoda shows himself to be an artful, masterful proponent of one of movie-making’s most tired tropes: the passing-of-time montage. He uses it to show romance blossoming (with meal preparation a huge part), pregnancy arriving (so much vomiting!), Hana boning up on homebirth, her children arriving. Once they move to the country, there’s a renovation montage (fixing roof, floorboards, windows, planting vegetables), then a sequence in which the kids explore the woods, hunting vermin, reptiles, birds. Later, there’s a training montage showing Ame learning from his sensei.

Training montages are also plentiful in The Boy and the Beast. They’re, of course, to show the progress of a pupil – learning discipline and devotion in both his domestic tasks and his martial-arts practice – but Hosoda uses this device to show great spans of time in motion. Making use of the animated medium, he moves fluidly forward: as Kumatetsu and Ren practice-spar, the years pass around them, Ren growing ever bigger as they do, the boy turning into a man without a cut. This is reminiscent of Hosoda’s greatest passing-of-time sequence, a single ‘tracking shot’ from Wolf Children. It begins on Ame’s first day of school and, as it tracks along the various classrooms, we move back and forth between him and his sister, seamlessly moving up grades, three years passing without an animated edit.

As well as having a gift for montages, Hosoda is, like many anime directors, obsessed with rendering the natural world. He shows snow falling in eddying, erratic patterns; pollen blown in the air; flowers, trees and powerlines wobbling in the wind; the heads of sunflowers hanging heavy; rain dripping from eaves; waterfalls spraying clouds of mist, sending water into mountain streams; lakes stilled, then rippling; spider webs glistening with the previous night’s rainfall; butterflies fluttering, dragonflies buzzing and sparrows flitting over green fields. He animates using photographic effects: isolated focus, both blurring out close figures or isolating them in shallow depth of field; sunlight bleeding into the ‘lens’; CCTV footage thick with grain; computer screens featuring a constant ‘roll’ imperceptible to the naked eye. When Hosoda pens the lyrics for a ‘theme song’ heard in Wolf Children’s end credits, we get an inside glimpse into the way he conceives of his films: ‘running in the snow, counting clouds / playing in the rain, being blown by the wind / buried under flowers, playing grass kazoos,’ sings Ann Sally. Similarly, the thematic power-ballad by Hanako Oku that turns up both in and at the end of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time begins: ‘your back, running on the baseball field / was freer than the clouds floating in the sky’. Mountainous cloud formations may be Hosoda’s number-one visual fetish, lovingly rendered – not just in all of the four films, but in the poster art for all four films – billowing and bulbous, piled up high above the horizon. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time finishes with its heroine, Makoto, standing on a baseball diamond, staring up at a giant mass of clouds, the horizon promising her the unknown, a young protagonist with her whole life – a life worth living – in front of her.

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/the-boy-and-the-beast

Endnotes

| 1 | See Mark Schilling, ‘Studio Ghibli’s New Film to Be Directed by Rival’, ScreenDaily, 2 September 2001, <http://www.screendaily.com/studio-ghiblis-new-film-to-be-directed-by-rival/406748.article>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Carlos Aguilar, ‘The Boy and the Beast Dir. Mamoru Hosoda on Shared Fatherhood & Why His Films Deal with Two Worlds’, Indiewire, 15 January 2016, <http://blogs.indiewire.com/sydneylevine/the-boy-and-the-beast-dir-mamoru-hosoda-on-shared-fatherhood-why-his-films-deal-with-two-worlds-20160115>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

| 3 | Mamoru Hosoda, in the featurette Direction File (A Talk with the Director Mamoru Hosoda), The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, DVD, Madman, 2009. |

| 4 | The term shōjo refers to ‘anime and manga […] aimed at girls between the ages of ten and eighteen’ that ‘tend to focus on romance and interpersonal relationships’, while shōnen is aimed at ‘young boys under the age of fifteen’, ‘have a young male hero’ and ‘are focused on action, adventure, and fighting’; see Richard Eisenbeis, ‘How to Identify the Basic Types of Anime and Manga’, Kotaku, 8 March 2014, <https://www.kotaku.com.au/2014/03/how-to-identify-the-basic-types-of-anime-and-manga/>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

| 5 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Aguilar, op. cit. |

| 6 | ibid. |

| 7 | bid. |

| 8 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Ryan Huff, ‘Interview with Wolf Children Director Mamoru Hosoda’, Madman website, 20 January 2014, <https://www.madman.com.au/news/interview-with-wolf-children-director-mamoru-hosoda/>, accessed 30 May 2017. |

| 9 | Yuki is voiced as a child by Momoka Ohno and as a teenager by Haru Kuroki, while Ame, by Amon Kabe and Yukito Nishii. |

| 10 | My Neighbor Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988). |

| 11 | Mamoru Hosoda, in the featurette Interview with Mamoru Hosoda, Summer Wars, DVD, Madman, 2011. |

| 12 | ibid. |