THE NFSA RESTORES COLLECTION: PART 57

In Celia (1989), writer/director Ann Turner engages with the intersection between the public realm and the experience of everyday life. Presented from the perspective of child protagonist Celia Carmichael (Rebecca Smart), Turner’s debut feature depicts – in saturated colours and golden light – the Melbourne suburbs of the late 1950s as a world of sleepovers, backyard barbecues, granny flats and leafy backyards. They are also revealed to be a place of parochialism and barely repressed brutality. Poised between the emotional realism of Celia’s subjectivity and the city’s documented past, Celia highlights multiple layers of history and reveals the local and personal impact of political events and decisions.

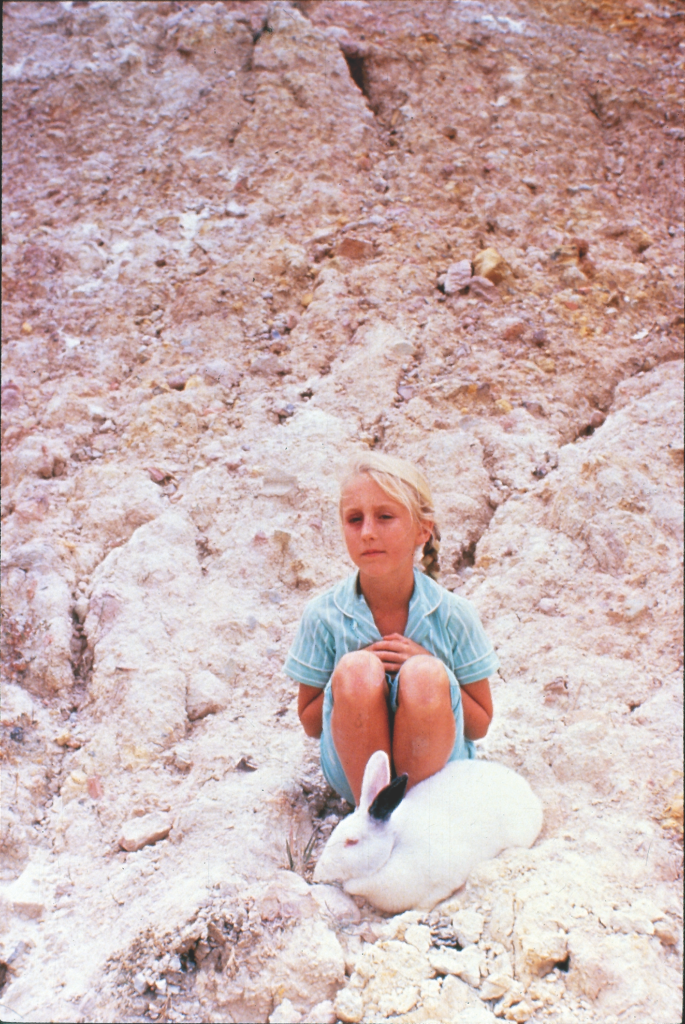

Turner’s initial inspiration for the Celia narrative was the Victorian rabbit ‘muster’ of 1958, in which pet rabbits were either euthanised or rounded up and sent to Melbourne Zoo as part of a government response to the threat posed by wild rabbits to farmland in the state.[1]See Ron Burnett, ‘Take the Bunny and Run: Memories of Childhood and Ann Turner’s Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 72, March 1989, p. 8; and ‘Zoo Rabbit Trouble’, The Age, 3 February 1958, p. 7. This ineffectual bureaucratic decision reached into the very heart of family life and, in Celia, becomes a metaphor for the vulnerability of the private realm to misdirected political power.

Vulnerability and violence: A synopsis

Celia is set in the comfortable middle-class Melbourne suburb of Surrey Hills, and the opening shot of the sequence that precedes the titles is idyllic: a small girl with flaxen plaits emerges within a sunny garden filled with birdsong; she is carefully balancing a teacup and saucer as she makes her way down the path to a green-painted granny flat. As soon as she goes inside, the mood changes: the golden summer light is replaced by a more ominous, red-hued gloom (created by red curtains), and Celia discovers that her adored grandmother (Margaret Ricketts) has died during the night.

The shock of this discovery and Celia’s ongoing grief and trauma are central to the events of the narrative as they play out. In the process of grappling with the immutable reality of death and the loss of her grandmother, she becomes both fascinated and haunted by the eponymous monsters of ‘The Hobyahs’, a nineteenth-century fairytale about gruesome fantastical creatures that come in the night to steal old ladies.[2]The tale was first published in The Journal of American Folklore in 1891. See Michelle De Stefani, ‘Taming the Hobyahs: Adapting and Re-visioning a British Tale in Australian Literature and Film’, TEXT, no. 43, October 2017, <http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue43/De%20Stefani.pdf>, accessed 2 June 2022. As a consequence of becoming aware of death and recognising it as the hidden underside of life, Celia experiences a critical moment of change, beginning to see the people around her through new eyes. This is further exacerbated by the dimming of her faith in the integrity of her father, Ray (Nicholas Eadie), and her secure and predictable middle-class childhood is increasingly revealed to be harbouring the kind of senseless cruelty and hatred that is given such graphic metaphorical expression in the story of the Hobyahs.

Moving seamlessly between Celia’s child’s-eye view and a faithful rendering of local, national and international historical events, Turner exposes postwar anxieties about social change and resistance to difference. In Celia, the difference that Ray is so determined to resist enters his life in the shape of new next-door neighbours the Tanners. Celia is instantly drawn to this family, particularly the energy and modern outlook of the mother, Alice (Victoria Longley), who, much to Celia’s fascination, plays with her children. Ironically, given his determined conformity, Ray also responds to Alice’s allure, but does this through predatory behaviour that highlights his hypocrisy and the toxic patriarchal underside of the 1950s nuclear family. He goes on to institute a personal witch-hunt against the communist Tanners, and is responsible for Alice’s husband, Evan (Martin Sharman), losing his job and having to move his family to Sydney where he can find work.

Alongside the tensions that play out around the Tanners, the rabbit muster that inspired the film is woven into the fabric of the narrative through the figure of Murgatroyd, Celia’s doomed pet rabbit. When the rabbit muster is declared, Murgatroyd is rounded up with relentless determination by local policeman and close family friend Sergeant John Burke (William Zappa) and taken to Melbourne Zoo. Murgatroyd becomes a form of litmus test relating to the integrity of the people in Celia’s life, revealing, in turn, Ray’s hypocrisy; John’s officious authoritarianism; the savagery of John’s daughter, school bully Stephanie (Amelia Frid); and the growing strength and independence of Celia’s mother, Pat (Mary-Anne Fahey). When Murgatroyd is found dead at the zoo, it has become increasingly apparent to Celia that her world is full of Hobyahs, intent on destroying everything she loves. Her fear and trauma reach their climax when John appears in the Carmichaels’ kitchen with a puppy as a peace offering; mistaking him for a Hobyah – or, arguably, seeing him in his true Hobyah colours – Celia shoots him dead with her father’s gun. For the viewer, this event is shocking and unexpected, but also appropriate and fitting within the film’s imaginative and narrative framework.

In the film’s final scene, the narrative returns to the quarry that, throughout the film, has acted as a wild zone associated with the children and their own culture of cruelty and aggression. This concluding scene acts as a form of coda to offer an alternative perspective on the events that have taken place, and to restate the power and meaning of the cultural space created and occupied by children. At this point, there has been a recalibration of the group dynamics. Celia is now leading a group comprising Stephanie and her allies as well as the gentle Heather (Clair Couttie). Heather has previously attempted to keep a foot in both Celia’s and Stephanie’s warring camps, but, having witnessed the shooting, has become bonded by blood to Celia. Celia, with the utmost confidence and authority, presides over a ritual hanging in which Heather is strung up in place of the ‘filthy man’ who murdered John. Celia pronounces that ‘justice has been done and the case rests forever’, and the children race off as a united group – albeit with the hapless Heather lagging behind.

Funding and production

Turner struggled to fund Celia’s production, with some investor reluctance relating to the original script’s political nature.[3]See Ina Bertrand, ‘Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 73, May 1989, p. 61. This was in spite of some impressive writing credentials that set her apart. She had received the award for best screenplay for her graduate film Flesh on Glass (1981)at Swinburne Technical College, and her script for Celia won the Australian Writers’ Guild’s Monte Miller Award for Best Unproduced Screenplay in 1984. It nevertheless took Turner three more years to raise the money to begin production in 1987. She was able to negotiate a deal between Hoyts, a distributor that would guarantee a cinema release, and the independent production company Seon Films. Film Victoria and the Australian Film Commission also provided funding. The A$1.4 million budget was very tight, and necessitated quite a bit of careful planning, ingenuity and goodwill. In his introduction for UK boutique DVD company Second Run’s 2009 release of the film, then–BFI National Archive curator Michael Brooke observes that one of the positives of the modest funding that Turner eventually managed to procure was that it allowed Celia to remain true to its original concept: ‘There was complete casting freedom, and no demands that a very Australian script be altered to appeal to an international audience.’[4]Michael Brooke, ‘Celia’, booklet essay, Celia,DVD, Second Run, 2009, pp. 3–9.

A particular strength of the film is the way its intensely local focus creates a microcosm that tells a much larger story relating to conservative paranoia, patriarchal authority and fear of difference.

A particular strength of the film is the way its intensely local focus creates a microcosm that tells a much larger story relating to conservative paranoia, patriarchal authority and fear of difference. Peta Lawson’s evocative production design is integral to the specificity of time and place that lends such assuredness to the narrative, as is Rose Chong’s costume design. In terms of casting, securing Smart – who had already impressed in the miniseries The Shiralee – for the lead role was particularly opportune. Turner had originally envisaged Celia as dark-haired, but Smart was the obvious choice, with her dimples and golden plaits adding to the film’s unsettling blurring of the line between appearance and reality. Other outstanding performances included those by Fahey and Longley, who received the film’s sole Australian Film Institute Award nominations; they were both nominated for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, with Longley winning the category. For the film’s cinematography, Turner was fortunate to have engaged Geoffrey Simpson, who created the disquieting and expressive contrast between the golden serenity of summer in the suburbs and the shadowy night-time world of the Hobyahs. As monsters seen through a child’s eyes, the Hobyahs’ blending of the kitsch and the uncanny was achieved through special-effects make-up, costume and carefully choreographed movement.[5]See Seon Films, Celia press kit, 1989, p. 3.

Reception and legacy

Celia was well reviewed at the time of its theatrical release, with critics responding to its representation of the hypocrisy of the adult world from a child’s perspective and its interweaving of the personal and the political. In his review for The Sydney Morning Herald, David Stratton compared the film to Fred Schepisi’s The Devil’s Playground (1976) in terms of its exploration of ‘the hypocrisy of a blinkered adult world against which the child rebels’;[6]David Stratton, ‘It’s Not All Child’s Play’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1989, p. 14. and, in Cinema Papers, Ina Bertrand noted the clarity of ‘the child’s-eye-view’ in exposing the ‘bigotry of the period’.[7]Bertrand, op. cit.

Celia nevertheless performed poorly at the Australian box office. There was undoubtedly a domestic audience for Australian cinema at this time, but it was hard to market due to being an adult film told from a child’s perspective. Prior to its release, executive producer Bryce Menzies commented:

Marketing is not a piece of cake on this one. It’s not a children’s film, it’s an adult picture, and distributors get very nervous if they think it’s a kid’s film because they don’t do so well.[8]Bryce Menzies, quoted in Brooke, op. cit.

With the benefit of hindsight, Turner has reflected that the film’s generic complexity also made it a hard sell at the time of its release:

I studied film at a time when you were encouraged to explore playing with genres, to not need to fit your film into one box […] Fresh from that experience, Celia became its own beast and didn’t fit easily into a particular genre. That certainly didn’t do it any favours at the box office, but it meant that it could be a story that wasn’t beholden to rigid rules, and that’s possibly helped it to have a long life.[9]Ann Turner, quoted in Craig Martin, ‘Trust Your Instinct: An Interview with Ann Turner’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016 <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/ann-turner-interview/>, accessed 20 April 2022.

The film retains this originality and unexpectedness when viewed today, while its uncanny blending of the real and the fantastical speaks to the present-day crisis of confidence in public narratives and surface appearances.

When Celia emerged at the end of the 1980s, Australians were not only falling out of love with homegrown period films in general, but also fairly indifferent to the 1950s nostalgia that had become a staple of American screen culture by this time. There is of course nothing nostalgic about Celia – it has been described as ‘anti-nostalgia’[10]Time Out review cited in ‘Ann Turner’s Films – What the Critics Said’, Ann Turner official website, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20170208224935/https://www.annturnerauthor.com/ann-turner-films-what-the-critics-said>, accessed 20 April 2022. – but, in the Australian films being made at this time as well as those that would make an impact in the 1990s, there was a significant move away from narratives set in the past. Representations of history had become associated with the ‘worthiness’ of ‘the AFC genre’, a term coined by Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka.[11]Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, Anatomy of a National Cinema, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2,Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, p. 28, Celia’s symbolic layering is not only a far cry from the episodic literalness described by Jacka and Dermody, but references some of the conventions of the Australian period film in order to challenge and upset audience expectations. In this case, its evocative period detail reflects a community that relies on conformity and convention to hide what is really going on.

In counterpoint to its lacklustre performance in Australian cinemas, Celia was a festival favourite: it had its world premiere in the Panorama section of the Berlin International Film Festival in February 1989; went on to win the Grand Prix at the Créteil International Women’s Film Festival; and continued to have an impressive run at festivals into the 1990s. The film also received a theatrical release across a wide range of countries including the UK, West Germany, Canada, Japan, Austria, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. At the time of Celia’s theatrical release in the UK, Hilary Mantel was one of many reviewers who engaged enthusiastically with its originality and the complexity of its representation of experience:

It is about childhood, but specifically about the point where the retributive fantasies of the child connect with the retributive fantasies of the adult world; and so in the broadest sense it is a political film.[12]Hilary Mantel, ‘The Violence of Children’, The Spectator, 31 March 1990, p. 43.

While only landing a limited theatrical release in the US, Celia’sarthouse status was confirmed with a screening in New York at the Museum of Modern Art in 1990 and a very respectful review from film critic Janet Maslin in The New York Times. Maslin described the film as a ‘transfixing, assured, extremely lucid attempt to see the world from Celia’s point of view’.[13]Janet Maslin, ‘A Child’s Response to the Tyranny of Grown-ups’, The New York Times, 19 March 1990, <https://www.nytimes.com/1990/03/19/movies/reviews-film-festival-a-child-s-response-to-the-tyranny-of-grown-ups.html>, accessed 20 April 2022. She also compared Celia’s ‘controlled, decorous style’ with ‘the deceptive serenity of a Blue Velvet [David Lynch, 1986]’,[14]ibid. an observation that foregrounds the uncanniness of the surface world presented in Celia, as well as Turner’s subtle but unsettling portrayal of the ordinary as ‘masking’ destructive elements of human nature and society. Maslin’s reference to Lynch prepares the way for twenty-first century readings of Celia through a horror lens that imbues the ordinary with danger and threat.

The (well-deserved) critical approval and festival recognition Celia received after its initial release related to its status as a quality independent film, and also to the sophistication of its exploration of childhood and politics within the microcosm of a sleepy Melbourne suburb. To mark Celia’s twenty-year anniversary in 2009, it was released on DVD in the UK by Second Run and in Australia by Umbrella Entertainment. To ensure home viewers could enjoy the best version of the film possible at this time, a new anamorphic transfer was made from original materials under Turner’s supervision.[15]See Celia DVD listing, Second Run website, <https://www.secondrundvd.com/release_celia.html>, accessed 21 April 2022. The Second Run release included a newly filmed interview with Turner and a booklet featuring excellent new essays written by Brooke and Australian historian Joy Damousi. The booklet also included the full text of the Australian version of ‘The Hobyahs’ that had made such an impression on Turner as a child, and that is so integral to the imaginary and figurative landscape of the film’s narrative. Celia’s inclusion in Second Run’s slate of new releases reconfirmed its status as a quality film and reconnected it to its arthouse roots. When the Institute of Contemporary Art in London marked Second Run’s ten-year anniversary with a special screening series, Celia was selected for the program by author Kim Newman, who described it as ‘one of the great movies about the terrors, wonders and strangeness of childhood, and a still-undervalued classic of Australian cinema’.[16]Kim Newman, quoted in ‘10 Years of Second Run: Kim Newman Selects and Marc Isaacs Introduces Celia’, Institute of Contemporary Arts website, 23 Sep 2015, <https://archive.ica.art/whats-on/10-years-second-run-kim-newman-selects-and-marc-isaacs-introduces-celia/>, accessed 21 April 2022. The company’s subsequent Blu-ray release of Celia in 2021 was made possible by a 2017 restoration of the film by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.[17]See ‘Celia: The Mask – Digital Restoration’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/celia-mask-digital-restoration>, accessed 3 June 2022.

Given a new life through its restoration, Celia was included in the Pioneering Women program curated by scholar Alexandra Heller-Nicholas as part of the 2017 Melbourne International Film Festival.[18]See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Why Pioneering Women?’, Melbourne International Film Festival blog, 1 August 2017, <https://miff.com.au/blog/view/4250/why-pioneering-women>, accessed 21 April 2022. The program had the aim of acknowledging the achievements of groundbreaking women directors working in the Australian screen industry in the 1980s and 1990s, with Heller-Nicholas choosing ten ‘should-be classics’.[19]Cameron Williams, ‘Redefining the Retrospective: Pioneering Women’, RealTime, 2 August 2017, <https://www.realtime.org.au/redefining-the-retrospective-pioneering-women>, accessed 21 April 2022. With a few notable exceptions, the contribution made by female filmmakers to twentieth-century Australian screen culture has been underappreciated; in describing the program and its organising logic, Heller-Nicholas observes that foregrounding the achievements of distinctive women filmmakers contributes to present-day discussions about the gender imbalance in the Australian film industry: ‘We know women can make rich, diverse, unique cinema not as some vague “maybe,” but because we have concrete evidence.’[20]Heller-Nicholas, quoted in Williams, ibid. In accounting for Celia’s relative obscurity, Heller-Nicholas refers to the interpretative challenge Turner’s experimentation with genre posed at the time of its release: ‘At the time [it] really confused critics with what we see now is its remarkable playfulness and spirit of experimentation with genre.’[21]ibid. Through its subversion of viewer expectations and its depiction of Australian suburban life as uncanny and cruel, Celia was ahead of its time.

Horror vs arthouse: Publicity and marketing

Alongside Celia’s identity as a great film that struggled to find not only an audience but also its rightful place in the Australian cinema canon, the film’s history has been significantly influenced by a series of marketing gambits designed to solve the problem of finding an audience for an adult film featuring a child protagonist. In Australia, the film was marketed in terms of Celia’s fantasy life and the film’s imaginary (‘A simple child’s story has captured her imagination … It may never let her go’), but other markets drew on the trope of the monstrous child to attract a wider audience through a focus on genre.[22]See Craig Martin, ‘Monsters, Masks and Murgatroyd: The Horror of Ann Turner’s Celia’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/horror-ann-turner-celia/>, accessed 3 June 2022. For Celia’s British theatrical release, the distributor had a bet each way. The film poster cited Derek Malcolm’s hugely appreciative review for The Guardian (‘Little short of miraculous … The most striking debut to reach us from Australia during the 80s’), while also emblazoning an image of Celia with the tagline ‘A tale of innocence corrupted’. In the image, Celia looks terrified as gruesome black talons reach out for her; the impression, as Brooke describes it, is of a ‘crude child-in-peril exploitation film’.[23]Brooke, op. cit., p. 9.

Albeit sensationalised, the British poster only alludes to the violence that takes the audience so much by surprise in Celia, but there was no such care to avoid spoilers in the artwork used for the 1990 VHS release in the United States. When distributor Trylon Video acquired the rights for the US home-viewing market, they had no interest in any prestige Celia had accrued on the festival circuit or as special-event cinema. Instead, they promoted Celia as an Ozploitation-style horror film, renaming it Celia: Child of Terror and giving it the tagline ‘the eerie, chilling tale of one child’s terror’. The cover art features a shot of Celia wearing bright red lipstick war paint and wielding the gun that will kill John. The red is repeated in the thickly daubed lettering of the title and in the background image of the burning house that often dominates Celia’s dreams. In combination with a reference to ‘shades-of-Carrie horror’ and a warning that ‘this is one kids film that’s made for adults’ in review excerpts, the packaging of the VHS builds a set of expectations that work against the grain of a narrative that so carefully balances the ordinary and the fantastical, and the personal and the social. This re-presentation of Celia as horror appears to have been an attempt to smooth out the very purposeful generic complexity that Turner had incorporated into the narrative. More than two decades later, US distributor Scorpion Releasing brought out a DVD of Celia that also packaged it as B-grade horror, under the ‘Katarina’s Nightmare Theater’ label.[24]See Martin, ‘Monsters, Masks and Murgatroyd’, op. cit.

In Australia, the film was marketed in terms of Celia’s fantasy life and the film’s imaginary, but other markets drew on the trope of the monstrous child to attract a wider audience through a focus on genre.

While Celia’s lowbrow shadow life in the US works at odds with, for example, Second Run’s aim in 2009 to return Celia to a cinephile audience, the film’s association with horror has become more intriguing in the decades that have followed its release. Over time, what may have begun as a reductive marketing strategy has evolved in line with changing perceptions of horror and its capacity to delve into past and present trauma. Most notably, the lens of horror proved productive in opening Celia up to a new audience through its selection for the opening night of the Stranger With My Face International Film Festival, a festival focusing on ‘female directors working in horror and related genres’.[25]‘About SWMF’, Stranger With My Face International Film Festival website, <https://www.strangerwithmyface.com/about-swmf/>, accessed 3 June 2022. When asked about giving Celia such a prominent position in the festival, co-founder and programmer Briony Kidd conceded that it was ‘a bit of a strange film to open a horror festival’, but alluded to its marketing in the United States and that ‘it has enough elements for people to think of it in that way’.[26]Briony Kidd, quoted in Rochelle Siemienowicz, ‘Get Familiar with the Stranger With My Face Film Festival’, SBS Movies, updated 24 February 2015, <https://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2014/08/19/get-familiar-stranger-my-face-film-festival>, accessed 21 April 2022. Moreover, while genre is about building audience expectations, it can also work as a provocation to make viewers alert to the subversion of genre norms.

In the case of Celia, an orchestrated tension develops between the overwrought and grief-stricken protagonist’s fantastical imaginings and the realist representation of external events in the adult world. Then, as the narrative plays out, external reality becomes increasingly unfathomable, and the adults in the ‘real’ world become less able to be trusted. In the film’s shocking and violent penultimate act, there is a grim logic in the way that the psychological horror of the Hobyahs becomes indistinguishable from an everyday world of petty tyranny and callous betrayal. Read with the grain, the scene where Celia shoots John could be described as a form of narrative invasion, in which the internalised fantastical realm overtakes/overwrites the real. And, indeed, this is how reviewers engaged with the film on its initial release. Mantel provocatively suggested that a viewer’s response to the ‘central final event is a matter of temperament, or perhaps a matter of what you can face’ – an observation that goes to the very heart of Turner’s exploration of the boundary between appearance and reality – while for others, Celia’s violent disruption of narrative and genre boundaries and expectations was perceived as a betrayal of the viewing contract. For instance, Stratton felt the film was not dark enough to signal and prepare the way for the narrative rupture wrought by the shooting;[27]Stratton, op. cit. and, despite name-checking Blue Velvet, Maslin observed that ‘when the film takes a lethal turn it seems to be going too far’.[28]Maslin, op. cit.

Horror in broad daylight

For an audience reading the film as horror from the very first appearance of the Hobyahs, on the other hand, the real is already monstrous. According to Turner, her experience with university students studying Celia has alerted her to the impulse for new – younger – audiences to give the psychological horror of the Hobyahs predominance in their reading of the film. ‘The students read Celia far more as a horror movie than a political/historical one,’ she has observed. ‘The Hobyahs at the start led the journey for their interpretation.’[29]Turner, quoted in Martin, ‘Trust Your Instinct’, op. cit. From this perspective, the quaint charm of the Surrey Hills neighbourhood and the suburban gentility of its inhabitants are perceived from the beginning to be a threat to Celia’s safety. With present-day audiences being more acutely aware of the vulnerability of children to the power wielded by adults in the guise of what is ordinary or normal, the eruption of violence in the film seems logical given the secrecy and repression that constitute its social and institutional landscape. The cold-hearted cruelty displayed by Stephanie and her gang adds to this disturbing portrayal of the dark underside of middle-class suburbia, particularly as her power and impunity stem from a chilling understanding of adult hypocrisy.

The unsettling sense that appearances cannot be trusted is established in Celia’s prologue with its allusion to ‘Little Red Riding Hood’: Celia is dressed in red as she heads along the garden path to make a delivery to her grandmother. In Charles Perrault’s version of the fairytale, not only has the grandmother been eaten by the wolf by the time Red Riding Hood arrives, but her unwary granddaughter will suffer the same fate due to her naivety. In contrast, by Celia’s penultimate sequence, its young protagonist has lost all trust in the safety and security of her environment and reacts with defensive aggression against the imagined threat posed by an uninvited visitor.

The Hobyahs that emerge from Celia’s unconscious after her grandmother dies accrue greater symbolic meaning as Celia loses faith in the authority of the adult world. The Hobyahs represent all that is left unsaid: the reality of death; the pain of grief and loss; family secrets and resentments; the petty injustices of institutional power; and the reactive absurdity of political decision-making. By foregrounding the destructive and ultimately fatal consequences of this culture of repression, Celia portrays how the public and private realms intersected during the 1950s and how, as Damousi describes, the conservative ideologies of the time drew on ‘fear and over-reaction’ to control and organise family and community life.[30]Joy Damousi, ‘Rabbit Unrest’, Vertigo, vol. 4, no. 3, Summer 2009, available at <https://www.closeupfilmcentre.com/vertigo_magazine/volume-4-issue-3-summer-2009/rabbit-unrest/>, accessed 3 June 2022.

Through the film’s centring of the real-life but farcical decision made by the Victorian state government of the time to ban pet rabbits, Turner highlights the political expediency of deflecting attention from a more complex problem by creating and then solving a different one.[31]Ann Turner, in the featurette Interview with Ann Turner, Celia, DVD, Second Run, 2009. In this case, rounding up pet rabbits in the city is offered up as a (completely ineffectual) solution to the rabbit plague destroying the livelihoods of farmers in the country. A similar process of deflection is enacted by Ray when he exposes Evan as a communist. Rather than being motivated by a sense of public duty, Ray’s actions are driven by his unresolved resentment about his own mother’s communist sympathies and his implication in her activities. They are also fuelled by his unrequited desire for Alice. His hypocrisy is exposed when the family has to leave for Sydney due to Ray’s actions and Steve (Alexander Hutchinson), the eldest Tanner child, observes, ‘If Mr Carmichael hadn’t tried to kiss Mum all the time, we could have stayed.’

Hierarchies of gender

While the domestic space in the 1950s was perceived as a retreat from the troubles of the outside world, the Carmichaels’ home foregrounds themes of appearance and reality and the repressive social control that comes with the pressure to conform. Within his own small family, Ray is the patriarch, often fun and loving but always in control. He is the decision-maker, while Pat quietly keeps the household running. Ray perceives his role within his family in terms of defending social norms relating to the preservation of the ‘Australian way of life’, a diffuse concept emerging out of 1950s Cold War ideology that, in historian Richard White’s words, ‘provided a mental bulwark against communism, against change, against cultural diversity’.[32]Richard White, Inventing Australia: Images and Identity, 1688–1980, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1981, p. 161. As historian Richard Waterhouse has argued, this worldview treated domesticity as an ‘expression of citizenship’, authenticating the inward-looking nuclear family and its connection to commodity culture.[33]Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman, South Melbourne, Vic., 1995, p. 201. For instance, although aware of Celia’s desperate desire for a pet rabbit, Ray is sure that he will be able to buy her off with an alternative gift of a Malvern Star bicycle (an iconic Melbourne-made status symbol). In this vein, an undercurrent of the cultural uniformity of the middle-class suburb in which Celia is set relates to the invisibility of the wider social change brought by postwar migration – change that was resisted during this period through assimilationist policies and normative social attitudes.[34]See White, op. cit., p. 160.

Informed by the cultural paranoia surrounding the communist threat to the status quo in the aftermath of World War II, Ray bears huge resentment towards his mother for her nonconformist politics. He perceives her participation in the peace movement as a denial of his contribution to protecting his country:

What do you think Uncle John and I would have done during the war? Let the Japs bayonet us and dig bamboo under our nails and say, ‘Thank you, honourable sirs, we love you,’ while they bombed Australia?

After his mother’s death, Ray’s determination to suppress the complexity of their shared history and conflicted relationship is initially expressed by locking up her backyard flat and forbidding Celia to enter. Subsequently, in a chilling scene that makes a mockery of his championing of freedom, he gathers up her books and burns them in a backyard bonfire.

Ray’s identity has become defined by self-deceit and fear of difference, but his determination to conform frequently conflicts with his love for his daughter. This makes Ray’s allegiances unpredictable – he whips Celia with his belt for throwing voodoo dolls through Stephanie’s window, but defends her right to keep Murgatroyd when John tries to seize her. Citing the containment and repression required to maintain the family as an institution, film critic Robin Wood has famously observed that horror is the genre where the ‘American family […] always rightly belonged’;[35]Robin Wood, ‘The American Family Comedy: From Meet Me in St. Louis to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’, Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, MI, 2018. accordingly, Ray’s abrupt shifts between fatherly affection, paranoia and arrogance render the family an unsafe space.

The Hobyahs represent all that is left unsaid: the reality of death; the pain of grief and loss; family secrets and resentments; the petty injustices of institutional power; and the reactive absurdity of political decision-making.

The representation of the nuclear family in Celia foregrounds issues around gender and power that emerge from the repressive politics that organise everyday life in the film’s present. With Ray as the head of the household, Pat is given little room for any kind of expression of opinion or identity; instead, it is her role to maintain order and keep up appearances. This work mostly remains invisible, but is communicated through costume and production design: Pat and Celia’s clothes are immaculate; the family home is neat and orderly; and dinner is a wholesome plate of meat and three veg. Pat is required to moderate her presence and remain as inconspicuous as possible in her role as wife and mother, perhaps as a counter to the powerful influence Ray’s mother has had on his life. Ironically, while the living and breathing Pat occupies a tentative and conditional place in her own household, Celia’s grandmother’s presence makes itself felt even after her death. She haunts the narrative, not just through Celia’s grief but also through Ray’s furious attempts to obliterate her memory and her influence. Pat’s submission to her husband’s point of view is further signalled at the barbecue when she suggests that Celia’s grandmother’s room needs to be cleared of her things because their presence is ‘unhealthy’.

Like Ray, Celia barely registers Pat’s personhood, but is attracted to the self-confidence and dynamic presence of Alice, who becomes a substitute for her grandmother. While Alice has a coincidental connection to Celia’s grandmother through their shared politics, her difference to those around her is initially indicated by her willingness to join in her children’s games, her substantial book collection and her indifference to cake-baking. That these small details should be indicators of her individuality speaks to the narrow parameters of the role allocated to women in 1950s society that, in White’s words, ‘worked to keep them in their place’.[36]White, op. cit., p. 165. In fact, as much as her social and political perspective reaches well beyond suburban Melbourne, even Alice is defined by her role as housewife and mother, and finds herself both belittled by and cleaning up after her male communist comrades. Strength emerges more effectively in female solidarity when Pat and Alice forge a connection based on Pat’s disillusionment with Ray.

In turn, Pat and Celia form an alliance through their growing awareness of Ray’s hypocrisy. Pat finds her voice initially within the family home when she stops Ray from whipping Celia with a belt, and subsequently in the public arena of parliamentary politics when she adds her voice to the ultimately successful protest movement against the pet rabbit muster. Despite her assertion of independence and the role she plays in this public resistance, however, Pat doesn’t provide Celia with the happy ending she wishes for. Instead, Murgatroyd’s sodden corpse represents the death of trust and a victory for the Hobyahs.

Celia’s narrative is not one that provides a resolution to or escape from the deceit and hypocrisy against which its protagonist struggles. The eruption of violence, in which Celia responds to the relentless mounting up of trauma by shooting what she thinks is the Hobyah, offers no release and only leads to further repression. At this point in the narrative, it becomes Pat’s responsibility to protect her daughter and preserve the family through her silence. The family dynamic has shifted, placing Celia and Pat in the powerful but also insidious position of the keepers of secrets. The pact between daughter and mother is described by Turner as Celia’s induction into the corrupt world of adulthood.[37]Turner, in Interview with Ann Turner, op. cit.

Secrets and lies

As well as being a film about adult bigotry and the limitations of public and private institutions, Celia is also a narrative about childhood. Rather than investing in either conventional understandings of youthful innocence or more sensationalist horror tropes relating to the evil child, Turner explores children’s culture as distinct from, but also responsive to, adult rules and behaviour. In an interview that accompanied the film’s initial release, she described how she drew on the emotional intensity of her own childhood friendships and experiences:

We either liked people enormously and would die for them, or we held them in a position of extreme dislike and they were enemies […] Our games were often very violent […] At the time it often seemed funny rather than violent.[38]Turner, quoted in Burnett, op. cit., p. 9.

The children lead an alternative life beyond the adult gaze, symbolised by the separate space of the quarry, which is the locus of bitter warfare between Stephanie’s gang and the one Celia forms with the Tanner children. In contrast to the deceit and petty vindictiveness exhibited by adults, the children are overtly and proudly partisan. Celia is resolute in her loyalty to the Tanner boys when John unfairly singles them out for punishment, and when her father betrays the Tanners’ father by reporting on him as a communist, Celia responds by joining with the Tanners in a ritual to express their fury at his mean-spirited duplicity (along with that displayed by John and Stephanie). Although the children exist and connect with one another in an alternative zone of experience, they are also products of their families: the monstrous Stephanie has been formed out of her father’s amoral pettiness; the open-hearted Tanners reflect their dynamic and principled parents; and Celia’s own forthright approach connects her to her free-thinking grandmother but also hints at a more functional family life disrupted by Cold War paranoia.

Within this sphere of childhood, with its fierce loyalties and partisan allegiances, Heather is an elusive and ambiguous character. Rarely speaking and seamlessly drifting between the two axes of power represented by Celia’s and Stephanie’s respective gangs, Heather could be regarded as either an impartial go-between or a double agent. She baulks at declaring her loyalty to Celia through a blood oath, and walks off hand in hand with Stephanie after the fight between the rival gangs. In the chilling episode in which Stephanie brands Murgatroyd, Heather looks on; her distress is undeniable, but she fails to intervene. In the context of a narrative about authoritarianism and intolerance, she is not a pacifist, but rather a bystander whose attempts to remain neutral make her complicit with Stephanie’s cruelty and duplicity.

Heather’s bystander status is disrupted when her own rabbit is found dead alongside Murgatroyd at the Zoo; and when Heather witnesses the shooting of John, she is required to declare her allegiance to Celia by finally taking the blood oath she has been avoiding. In the final scene, Celia presides over Heather’s symbolic hanging – partly to punish her for her divided allegiances, partly to give Stephanie the opportunity to avenge her father’s death, but mostly to allow Celia to divest herself of any guilt or responsibility for the shooting. Heather’s status has changed from bystander to stand-in. After John’s death and its subsequent cover-up, the Hobyah isn’t destroyed but finds a new host in Celia, who now delights in wielding the power of the tormentor. She has learned the lessons of a corrupt adult world organised around hypocrisy, deflection and intimidation, and both Stephanie and Heather defer to her authority. While one contemporaneous review complained that Celia ‘suffers from having more than one ending’,[39]Bertrand, op. cit., p. 61. the film’s coda is integral to an understanding of the way that societies based on repression replicate themselves, and that a failure to come to terms with past and present trauma curses future generations.

The resonance of this ‘ending’, which refuses resolution through any kind of restoration of childhood innocence, opens the narrative up to the wider reality that exists beyond the margins of Celia’s insular suburban setting. There is no innocence or resolution to be found in a community so wholeheartedly committed to the preservation of surface appearances and a status quo based on silence and the suppression of dissent.

Celia was released in 1989, the year following the official celebration of the bicentenary of the colonisation of Australia marked by the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. This anniversary was countered with an alternative history of invasion that articulated the dispossession and loss experienced by Australia’s First Peoples.[40]See Kate Darian-Smith, ‘Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: A Long History of Celebration and Contestation’, The Conversation, 26 January 2017, <https://theconversation.com/australia-day-invasion-day-survival-day-a-long-history-of-celebration-and-contestation-70278>, accessed 3 June 2022. In the narrative of Celia, the brutal reality of colonisation is the unacknowledged shadow side of the placid suburban ordinariness that is policed with such determination. For Ray, the Tanners’ politics and the rabbit plague threaten the security of everyday life and are to be resisted, but he is oblivious to the fact that his comfortable life is built on unacknowledged trauma and a history of denial.

In Celia, the rabbit plague is the return of the repressed, a grim eruption of a national unconscious that refuses to acknowledge the trauma of colonisation. The only people of colour seen within the hermetic microcosm of Celia’s neighbourhood are represented through the racist stereotypes and crude exoticism of King of the Zombies (Jean Yarbrough, 1941),the film screened during the Carmichael family’s second visit to the cinema. In King of the Zombies, the expression of difference as ‘Other’ is channelled through the horror motif of the ‘living dead’, a figure that represents what won’t be repressed. The children draw on the film’s depiction of ritual when they burn effigies of their enemies to channel their resistance to the repressive power wielded within their community. Subsequently, in Celia’s chilling conclusion, the symbolic hanging sees the children again enacting an appropriated ritual. In this case, the source of their knowledge exists outside the diegesis, implicating the children in a history of violence and exclusion.

With reference to Celia, Heller-Nicholas suggests that ‘horror is feeling history through the gut’.[41]Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, in the featurette There’s Something About Celia, Celia, Blu-ray, Second Run, 2021. In Turner’s layered exploration of all that remains unsaid in Australian postcolonial society, the ordinary and the everyday are haunted by a failure to acknowledge responsibility and speak the truth. In Celia, the domestic space of the suburban home is rendered uncanny by the determination to choose appearance over reality. Celia’s child’s-eye view is not innocent – this is not an innocent world – but a terrifying and terrified awareness of the secrets and lies on which her world is built. She is, indeed, ‘a child of terror’.

Select bibliography

Ina Bertrand, ‘Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 73, May 1989, p. 61.

Michael Brooke, ‘Celia’, booklet essay, Celia, DVD, Second Run, 2009, pp. 3–9.

Ron Burnett, ‘Take the Bunny and Run: Memories of Childhood and Ann Turner’s Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 72, March 1989, pp. 6–10.

Joy Damousi, ‘Rabbit Unrest’, Vertigo, vol. 4, no. 3, Summer 2009, available at <https://www.closeupfilmcentre.com/vertigo_magazine/volume-4-issue-3-summer-2009/rabbit-unrest/>.

Michelle De Stefani, ‘Taming the Hobyahs: Adapting and Re-visioning a British Tale in Australian Literature and Film’, TEXT, no. 43, October 2017, <http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue43/De%20Stefani.pdf>.

Craig Martin, ‘Monsters, Masks and Murgatroyd: The Horror of Ann Turner’s Celia’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/horror-ann-turner-celia/>.

Craig Martin, ‘Trust Your Instinct: An Interview with Ann Turner’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016, <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/ann-turner-interview/>.

Janet Maslin, ‘A Child’s Response to the Tyranny of Grown-ups’, The New York Times, 19 March 1990, <https://www.nytimes.com/1990/03/19/movies/reviews-film-festival-a-child-s-response-to-the-tyranny-of-grown-ups.html>.

Cameron Williams, ‘Redefining the Retrospective: Pioneering Women’, RealTime, 2 August 2017, <https://www.realtime.org.au/redefining-the-retrospective-pioneering-women>.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1989 Length 102 minutes Production Company Seon Films Producers Timothy White, Gordon Glenn Director Ann Turner Writer Ann Turner Director of Photography Geoffrey Simpson Editor Ken Sallows Production Designer Peta Lawson Costume Designer Rose Chong Music Chris Neal

MAIN CAST

Celia Carmichael Rebecca Smart Ray Carmichael Nicholas Eadie Alice Tanner Victoria Longley Pat Carmichael Mary-Anne Fahey Granny Margaret Ricketts Steve Tanner Alexander Hutchinson Karl Tanner Adrian Mitchell Meryl Tanner Callie Gray Evan Tanner Martin Sharman Heather Goldman Clair Couttie Mr. Goldman Alex Menglet Stephanie Burke Amelia Frid Sergeant John Burke William Zappa

Endnotes

| 1 | See Ron Burnett, ‘Take the Bunny and Run: Memories of Childhood and Ann Turner’s Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 72, March 1989, p. 8; and ‘Zoo Rabbit Trouble’, The Age, 3 February 1958, p. 7. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The tale was first published in The Journal of American Folklore in 1891. See Michelle De Stefani, ‘Taming the Hobyahs: Adapting and Re-visioning a British Tale in Australian Literature and Film’, TEXT, no. 43, October 2017, <http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue43/De%20Stefani.pdf>, accessed 2 June 2022. |

| 3 | See Ina Bertrand, ‘Celia’, Cinema Papers, no. 73, May 1989, p. 61. |

| 4 | Michael Brooke, ‘Celia’, booklet essay, Celia,DVD, Second Run, 2009, pp. 3–9. |

| 5 | See Seon Films, Celia press kit, 1989, p. 3. |

| 6 | David Stratton, ‘It’s Not All Child’s Play’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1989, p. 14. |

| 7 | Bertrand, op. cit. |

| 8 | Bryce Menzies, quoted in Brooke, op. cit. |

| 9 | Ann Turner, quoted in Craig Martin, ‘Trust Your Instinct: An Interview with Ann Turner’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016 <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/ann-turner-interview/>, accessed 20 April 2022. |

| 10 | Time Out review cited in ‘Ann Turner’s Films – What the Critics Said’, Ann Turner official website, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20170208224935/https://www.annturnerauthor.com/ann-turner-films-what-the-critics-said>, accessed 20 April 2022. |

| 11 | Susan Dermody & Elizabeth Jacka, Anatomy of a National Cinema, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2,Currency Press, Sydney, 1988, p. 28, |

| 12 | Hilary Mantel, ‘The Violence of Children’, The Spectator, 31 March 1990, p. 43. |

| 13 | Janet Maslin, ‘A Child’s Response to the Tyranny of Grown-ups’, The New York Times, 19 March 1990, <https://www.nytimes.com/1990/03/19/movies/reviews-film-festival-a-child-s-response-to-the-tyranny-of-grown-ups.html>, accessed 20 April 2022. |

| 14 | ibid. |

| 15 | See Celia DVD listing, Second Run website, <https://www.secondrundvd.com/release_celia.html>, accessed 21 April 2022. |

| 16 | Kim Newman, quoted in ‘10 Years of Second Run: Kim Newman Selects and Marc Isaacs Introduces Celia’, Institute of Contemporary Arts website, 23 Sep 2015, <https://archive.ica.art/whats-on/10-years-second-run-kim-newman-selects-and-marc-isaacs-introduces-celia/>, accessed 21 April 2022. |

| 17 | See ‘Celia: The Mask – Digital Restoration’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/celia-mask-digital-restoration>, accessed 3 June 2022. |

| 18 | See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Why Pioneering Women?’, Melbourne International Film Festival blog, 1 August 2017, <https://miff.com.au/blog/view/4250/why-pioneering-women>, accessed 21 April 2022. |

| 19 | Cameron Williams, ‘Redefining the Retrospective: Pioneering Women’, RealTime, 2 August 2017, <https://www.realtime.org.au/redefining-the-retrospective-pioneering-women>, accessed 21 April 2022. |

| 20 | Heller-Nicholas, quoted in Williams, ibid. |

| 21 | ibid. |

| 22 | See Craig Martin, ‘Monsters, Masks and Murgatroyd: The Horror of Ann Turner’s Celia’, Senses of Cinema, no. 81, December 2016, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/beyond-the-babadook/horror-ann-turner-celia/>, accessed 3 June 2022. |

| 23 | Brooke, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 24 | See Martin, ‘Monsters, Masks and Murgatroyd’, op. cit. |

| 25 | ‘About SWMF’, Stranger With My Face International Film Festival website, <https://www.strangerwithmyface.com/about-swmf/>, accessed 3 June 2022. |

| 26 | Briony Kidd, quoted in Rochelle Siemienowicz, ‘Get Familiar with the Stranger With My Face Film Festival’, SBS Movies, updated 24 February 2015, <https://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2014/08/19/get-familiar-stranger-my-face-film-festival>, accessed 21 April 2022. |

| 27 | Stratton, op. cit. |

| 28 | Maslin, op. cit. |

| 29 | Turner, quoted in Martin, ‘Trust Your Instinct’, op. cit. |

| 30 | Joy Damousi, ‘Rabbit Unrest’, Vertigo, vol. 4, no. 3, Summer 2009, available at <https://www.closeupfilmcentre.com/vertigo_magazine/volume-4-issue-3-summer-2009/rabbit-unrest/>, accessed 3 June 2022. |

| 31 | Ann Turner, in the featurette Interview with Ann Turner, Celia, DVD, Second Run, 2009. |

| 32 | Richard White, Inventing Australia: Images and Identity, 1688–1980, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1981, p. 161. |

| 33 | Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman, South Melbourne, Vic., 1995, p. 201. |

| 34 | See White, op. cit., p. 160. |

| 35 | Robin Wood, ‘The American Family Comedy: From Meet Me in St. Louis to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’, Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, MI, 2018. |

| 36 | White, op. cit., p. 165. |

| 37 | Turner, in Interview with Ann Turner, op. cit. |

| 38 | Turner, quoted in Burnett, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 39 | Bertrand, op. cit., p. 61. |

| 40 | See Kate Darian-Smith, ‘Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: A Long History of Celebration and Contestation’, The Conversation, 26 January 2017, <https://theconversation.com/australia-day-invasion-day-survival-day-a-long-history-of-celebration-and-contestation-70278>, accessed 3 June 2022. |

| 41 | Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, in the featurette There’s Something About Celia, Celia, Blu-ray, Second Run, 2021. |