When the great Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène died in June 2007, Western responses were rather muted compared to the copious outpourings that would follow the deaths of European art-cinema giants Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni the very next month. Nevertheless, the passing of this commonly designated ‘father of African cinema’[1]See Sheila Whitaker, ‘Ousmane Sembène’, The Guardian, 12 June 2007, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/jun/11/obituaries>, accessed 27 May 2020. elicited – by the usual Eurocentric Western standards – relatively extensive comment (especially in France, with which he had a long if sometimes fraught personal, artistic and political relationship) via obituaries recounting and often praising his remarkable and genuinely trailblazing dual literary and filmmaking careers. Happily, Sembène left us with an entirely fitting final feature film, Moolaadé (2004). Summarising themes and reworking filmmaking strategies from across his remarkable four decades as a director while adding both a new subject focus and refined formal elements to his cinema, Moolaadé is an at once localised and globally minded iteration of Sembène’s distinctly and unflaggingly ‘engaged’ revolutionary art, an elaborate and quietly radical charting of the historically palimpsestic, diffuse and contingent nature of power, space and change.

A cinematic griot

Commentators have long cited Ousmane Sembène’s vision of cinema’s purpose as political art being ‘a continuation of the work of the griot’ – a kind of traditional West African bard or troubadour – ‘by other means’.[2]Louis Ndong, ‘The Use of Languages as Linguistic Militancy in Ousmane Sembène’s Films: Between Film Aesthetics and Cinematographic Reception’, African Renaissance, vol. 14, no. 3/4, September–December 2017, p. 59. Emphasis added. In this understanding, a historically informed reality, no matter its temporal setting, is rendered on screen accompanied by commentary via a kind of participant-observer – a commentary mounting provocations to the viewer-listener from within the fiction, rather than from a position of claimed objectivity. The result, writes African cinema scholar Jude G Akudinobi, is a kind of ‘night school, a vision of African cinema firmly tied to a transformative function’ through the creation of films ‘advocating an explicitly elucidative, provocative, activist cinema’.[3]Jude G Akudinobi, ‘Durable Dreams: Dissent, Critique, and Creativity in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé’, Meridians, vol. 6, no. 2, 2006, p. 177. Closely connected to this idea is the role and importance of linguistic specificity, diversity and enunciation.

Bringing together a mix of local ‘authenticity’ in the form of multiple languages spoken on screen and a non-naive version of realism rendered through the notion of the ‘cinematic griot’ is an overall sense of performativity encapsulating actors, camera and authorship. The result in the case of Moolaadé is a film that presents very real problems while avoiding claims to transparency or naturalism. This notion of the performative is encapsulated in the director’s approach to mise en scène. ‘Sembène’s mise en scène is antinaturalistic’, African history and film scholar Marissa J Moorman writes of Moolaadé:

From acting style to costumes to props, the viewer’s attention is constantly drawn to the fact of performance and of framing. Camera work reinforces this. Tilted camera angles remind us that we are swooping with the camera into the compound near the beginning of the film, for example.[4]Marissa J Moorman, ‘Radio Remediated: Sissako’s Life on Earth and Sembène’s Moolaadé’, Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, Fall 2017, pp. 111–2. Emphasis removed.

The film’s presentation of very real-world, material and, indeed, political problems – via precise, prominent use of appropriate linguistic and cultural details, by way of the emphasis on performativity and reflexivity rather than representational claims – marks Sembène’s work at large, reaching its most precise, nuanced form with Moolaadé. While this final film occasionally features an actual griot figure on screen, it is the filmmaker’s own voice, through the trademark mix of local material and historical fidelity (or ‘grit’), subjective enunciation, and political analysis that most palpably suggests this role.[5]See Jen Westmoreland Bouchard, ‘Portrait of a Contemporary Griot: Orality in the Films and Novels of Ousmane Sembène’, The Journal of African Literature, no. 6, 2009.

Just as naturalism and representational realism are eschewed, Sembène’s emphasis on linguistic and cultural context is not in the name of nativist colour. As a writer and filmmaker with abiding Marxist convictions, he offers no ahistorical, ‘ontological’ African identity or identities. Rather, as postcolonial African cinema scholar Samba Diop writes,

not overly concerned with a mythical and vain–glorious African past even though he treats the historical past in some of his films, Sembène wants to bring forth the idea of a usable past, in other words, to use the past in order to shed light on the present.[6]Samba Diop, ‘Music and Narrative in Five Films by Ousmane Sembène’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 1, no. 2, 2009, p. 208.

A scathing charter of both French colonialism and corrupt post- and neo-colonial regimes, Sembène is just as hard on indigenous sources of regressive patriarchal, religious, socio-economic and political power.

Sembène’s work invokes the past and associated ongoing traditions primarily where the twin challenges of elusive freedom and equality for everyday people can thereby be better understood and furthered. Unlike familiar binary constructions (often spanning diverse ideological terrain) wherein modernity is a story of essential progress and tradition usually equals conservatism and enslavement, Sembène’s political modernism isolates strains of radical potential and ongoing regression in both the past and the present. This transhistorical critique and engagement reaches its clearest and most sophisticated expression in Moolaadé.

A subtly radical swan song

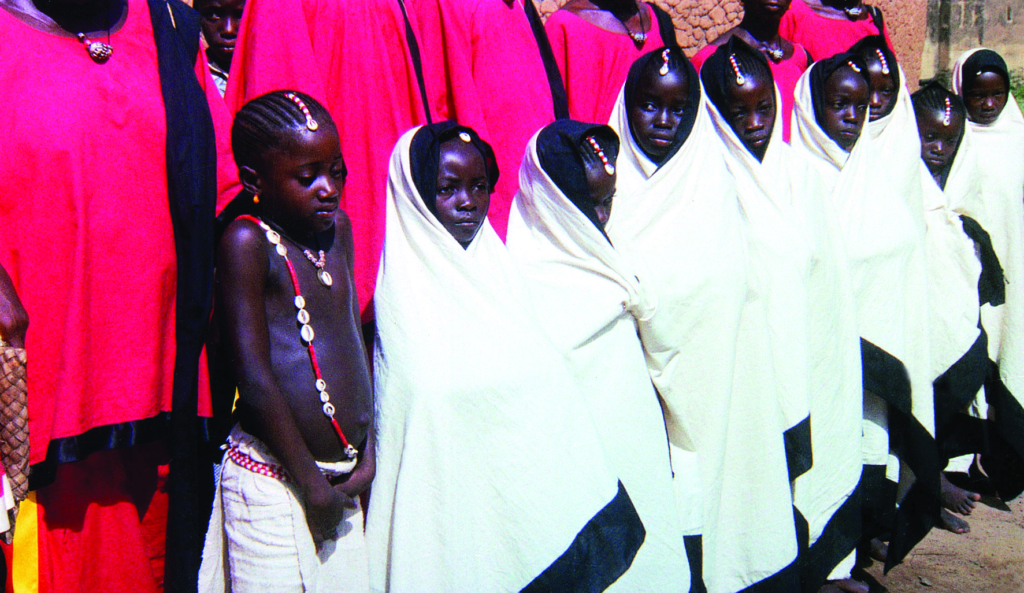

Featuring actors and crew from Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, Morocco, Tunisia, Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire, Moolaadé was reportedly considered by Sembène to be ‘the most African of his films’.[7]Ndong, op. cit., p. 59. Along with Faat Kiné (2001), he apparently conceived of Moolaadé and its never-made follow-up as comprising what Akudinobi describes as a trilogy ‘to honour everyday heroism, challenge certain assumptions about African womanhood, and remarkably demonstrate a range of contexts and indigenous precepts from which alternative modes of dissent, being, and liberation can spring’.[8]Akudinobi, op. cit., p. 177. In the case of this final film, the story features a complicated, stuttering resistance to female genital mutilation in a small West African village against the dictates of its Islamic patriarchs and their female enforcers. This resistance achieves apparent success by invoking another tradition or belief known as the moolaadé, the protective nature of which is symbolised when the rebellion’s notional figurehead, Collé Gallo Ardo Sy (Fatoumata Coulibaly), erects a coloured rope across the doorway of her family compound, which thereby becomes a kind of sanctuary.

On the surface maintaining a relatively light touch and even genuine humour despite its subject matter, Moolaadé’s approach to narrative, aesthetic form and character psychology may be more familiar to Western and other audiences than that of some of the director’s previous work. But the colourful and often very beautiful, immaculately framed and thematically resonant images also work to seduce the viewer into engaging with a film that articulates with absolute clarity and power that progress is not achieved by ‘roping off’ the past.[9]Akudinobi cites an Australian review, whose title – ‘Roping Out the Horrors of the Past’ – demonstrates the problem of Western responses that maintain a binary understanding of history, as an example of ‘the hermeneutic dangers that African films and institutions face as they traverse global cultural zones’. See ibid., p. 188. While the past may be riddled with well-known oppression and violence, this film shows how it also contains hidden revolutionary potential – and that the present is no different. Both are thereby connected not only intimately, but also in palimpsestic, contingent but non-linear ways, the film showing sediments of radical possibility hidden beneath a dominant religious and patriarchal regime.

The two most striking, symbolically loaded images demonstrating the shrouded revolutionary potential of such palimpsestic history are those directly associated with the idea from which the film gets its title, moolaadé – a pre-Islamic force that may be translated loosely as ‘magical protection’, and that Sembène defined as ‘sanctuary, asylum and the right to protection’.[10]Ousmane Sembène, quoted in Jacqueline Fitzgerald, ‘Stand Against Genital Mutilation’, Chicago Tribune, 1 December 2004, <https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2004-12-01-0412010043-story.html>, accessed 27 May 2020. These two images are: the ant hill that stands near the mosque at the centre of the village, the home of what the community believes is an ancient spirit known as the moolaadé; and the rope with which Collé cordons off her compound, invoking this ancient power. Embodying the spirit of the village’s first king, killed by his subjects in an act of rebellion as punishment for violent and oppressive rule, the moolaadé is said by local folklore to dwell within (or perhaps itself comprise) this ant hill. Housing an entirely local power born of the revolt by the villagers’ ancient ancestors, the ant hill predates the neighbouring mosque that was built upon the community’s conversion to Islam. While marking potentially competing histories, beliefs and political power, these two structures sitting side by side, according to Ugandan literature professor Dominica Dipio, demonstrate for the village patriarchs the ‘incontestable connection between their tradition and Islam’,[11]Dominica Dipio, ‘Gender Wars Around Religion and Tradition in Sembène Ousmane’s Moolaadé’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010, pp. 128–9. and thereby the dual-strength nature of their ongoing rule encompassing pre- and post-Islamic conversion and the resulting cultural and political hybridisation. But the real, if until now suppressed, historical contradiction between these metaphysical and political poles is unleashed when Collé calls upon the protective power of the moolaadé to shelter prepubescent girls fleeing the ritual of genital mutilation. Enforced by women known as the salindana, who are charged with administering the ritual – significantly enough, carrying it out just outside the village – and implicitly supported by both men and some other women, this mutilation is, the community’s rulers insist, a Muslim dictate. With its origins going back further than the Islam practised and enforced (in selective form) by the elders, the moolaadé, we are told by the latter in frustration, cannot be breached or undone except by the person who first invoked it. The film thereby shows how, rather than requiring secular-humanitarian intervention from outsiders, the means to progressive change can lie within a community itself through the harnessing of potentially revolutionary forces germane to a local culture and its hybrid belief systems and palimpsestic history.

To focus on the problem of female genital mutilation can chime with Western stereotypes about Africa’s ‘barbaric’ cultural practices. Crucially, however, the film suggests no recourse to first-world political or NGO-type interference.

Zimbabwean media studies scholar Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro argues that Collé’s control over the moolaadé and the reason for its invocation suggest ‘a social justice traditional system [that] is not gendered and therefore offers both male and female parties the potential to negotiate the power dynamics at work in their society’.[12]Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro, ‘The Representation of African Womanhood in Sembène’s Moolaadé: An Africana Womanist Reading’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 9, no. 2/3, 2017, p. 251. This enables the film to set up one of its core themes, a central paradox of patriarchal societies often commented on by feminists in the West and beyond: while men concern themselves with political, economic, moral and religious control in society at large, they are, in the process, often absent from the society’s everyday workings due to travelling on political missions or communing for extended sessions in the mosque. By being tasked to run the domestic sphere and enabling family and social life to function on the material level, women have room to manoeuvre when it comes to upsetting the system ‘at home’, especially if they come together in doing so. Dipio writes of the way that Sembène charts the shifting and forever-fluid politics of the village’s starkly gendered regime of space, highlighting how women, as subjects ensuring the mechanics of the everyday – while being positioned in social structures designed from above to limit their power – thereby have increased motivation and are more likely agents of potential revolutionary change compared to the largely absent men:

Women dominate, both in terms of their physical presence and the roles they play in the film. The actions in the film, just like the life in the community, are driven by them. Their presence and contributions are evident in mundane activities, as the opening sequence of the film makes clear. The director plays with the irony of the dominance of this physical presence of the women and their absence in decision–making, even in matters that affect their health and well–being […] While the women are associated with the material, the men are portrayed as the custodians of the ideological, the mythical and the spiritual.[13]Dipio, op. cit., p. 125.

Throughout Moolaadé, we are reminded of this latent material and thereby potentially real political power, and that it can only amount to anything when women achieve substantial solidarity. On the one hand, African cinema and media theorist Sheila Petty writes, this results in the portrayal of ‘a female domestic space circumscribed within caring for family and home, and seems to imply that this is a community that is secure in its practice of traditional values’.[14]Sheila Petty, ‘Postcolonial Transformations: From Emitaï (Sembène 1971) to Moolaadé (Sembène 2004)’, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 2011, p. 332. On the other, we increasingly see how women possess a very different kind of potential agency through their assigned roles, and the degree to which this patriarchally defined culture relies on them.

One of the formal means Sembène uses to demonstrate the importance of this very female-aligned material space is select employment of parallel-editing and cross-cutting techniques. This is how the viewer gleans most clearly that the film’s story is not about one woman or one moment in time, or even perhaps one village (even though Moolaadé never shows us another space), but rather a potential rupture in the political order taking in the most immediate domestic and village levels, events occurring nearby, and much further afield. Discussing the cross-cut sequence connecting close-up shots of Collé as she experiences painful sex with her husband, Ciré (Rasmané Ouédraogo), and images of the girls imprisoned at the ritual-circumcision site, Dipio writes of the

link between excision in childhood and the woman’s sacrifice of sexual pleasure throughout life. The salindana’s painful operation on a struggling child is inter–cut with Ciré making love to Collé [… who] is wounded just like the little girl pinned down by the salindana.[15]Dipio, op. cit., p. 131.

Using such cross-cutting as well as parallel editing elsewhere to show the village’s multiple spaces and their connections regarding both patriarchal power and its potential sources of challenge, the film allows the viewer time to take in the sheer beauty and performative life of this milieu. But such often-seductive aesthetics ought not to blind the viewer to the film’s political impulse, nor its genuine risk.

On the surface at least, to focus on the problem of female genital mutilation can chime with Western stereotypes about Africa’s ‘barbaric’ cultural practices. Crucially, however, the film suggests no recourse to first-world political or NGO-type interference. Chikafa-Chipiro summarises the potential impasse here:

Moolaadé elicits multifaceted readings where on the one hand Sembène is viewed as a champion of African women’s cause by bringing to light the misogynistic practice of ‘FGM’ while at the same time he may be condemned for reproducing an imperialistic, pornotropic and/or western feminist narrative of African barbarism, although the practice of FGM was not only practised in Africa.[16]Chikafa-Chipiro, op. cit., p. 249.

Rather than invoking privileged psychological modes wherein individual subjects drive a story forward – and, thereby, further resonate with familiar calls for a liberal interventionism celebrating heroic, Western-approved or -provided figures at the local and global levels – familiar Hollywood character-building techniques such as cross-cutting can also work to very different purposes, ends that Sembène has long pursued.

Sequences like the one evoked by Dipio above have an effect less of further enforcing Collé as the primary and thereby special and privileged agent of this story than of quietly emphasising a non-individuated understanding of history and potential revolutionary change – an approach familiar from previous Sembène films, and befitting his politics. The closer we look at precisely how the narrative is driven forward, the less it – including the film’s apparently triumphant conclusion – appears to have a singular causal agent. ‘Collé comes off as victorious despite her hurt body’, writes Chikafa-Chipiro of her enduring a public whipping by Ciré.[17]ibid., p. 256. But to treat Moolaadé’s final scene as confirming yet another case of protagonistic action would be to simplify and ultimately overlook the more diffuse, historically palimpsestic way Sembène tells this story – in other words, where transformative power really lies.

Collé’s initial gesture of offering the young girls protection is obviously crucial to the film, but it is also easy to overlook that she takes them in at her own daughter Amsatou’s (Salimata Traoré) insistence, following some initial hesitation. At first, Collé doesn’t seem at all interested in starting a political revolt, initially demanding the girls leave and even threatening them. The gradually ensuing resistance to regressive tradition that then grows among some of the women is very much born of modest initial actions, and lives through concurrently strong and fragile female solidarity. When she later tires of the struggle, fresh determination comes from other women within her own family (first, her husband’s eldest wife) and then beyond it, including those who initially opposed Collé’s behaviour. The potential lies in a combination of the material and solidary therein: women’s historical, communal suffering, but also the latent power hidden within their assigned domestic roles. For Moolaadé to downplay the importance of this would not only be to overlay the social reality Sembène presents with a kind of idealistic wish fulfilment highly familiar from Western cinema and political culture at its liberal-humanitarian apogee (or nadir), but also entirely out of keeping with this Marxist filmmaker’s previous work and sensibility.

Contingent power, mutating social space

In this film, power – be it that of the gradually developing, notional protagonist or the village patriarchs – is never secure. At one point, a high-angle crane shot shows Collé in her family compound standing in the middle of the seated girls, seemingly in a position of some authority as the protector of extremely vulnerable minors. In an adjoining scene, the senior wife gives Collé orders, as befits the family pecking order. Yet, just as the girls’ desperation, victimhood and lack of power started a chain reaction enabling the exercise of remarkable female agency, her painful sex with Ciré leads directly to growing solidarity with his other two wives when they subsequently treat her wounds. And when Ciré eventually succumbs to more hardline patriarchal pressure via his brother’s insistence that the unruly wife be brought to heel, publicly whipping her in an attempt to force an end to the moolaadé, she is concurrently – like the girls at the story’s genesis – at her most vulnerable and desperate while also on the brink of real change, embodying a dramatic conduit for female-driven and -affected social revolution finally played out on the highly theatrical space of the village square.

The theatre-like whipping scene exemplifies the film’s presentation of power as always contingent and thereby potentially undermined due to the inherently social nature of space. This is driven home through Sembène’s approach to framing throughout the film, showing different figures wielding meaningful agency, then losing it. At any moment, power can give way to the constantly mutating political reality of theatricalised social space, which thereby becomes the stage for entirely contingent portrayals of individual and group agency. At the heart of this contingency is a fundamental ambiguity and instability when it comes to rigid enforcements of gender ideology, despite the apparently unyielding patriarchal society at hand.

The charting of power undertaken by the film includes seen and unseen forces, the latter encapsulating both the religious (or mystical) and ‘ancient’, along with secular, ‘modern’ ones. In circles of almost infinite dimension, spanning the intimate to the social and the global, here is a portrayal of space featuring multiple contested sites and meanings. While the world beyond the village and immediate surrounds is never seen as such, its physical manifestations are apparent on screen in the form of the women’s radios, the aerial antenna and consumer goods at the stall run by the important character of Mercenaire (Dominique Zeïda). The latter, along with Ibrahima (Théophile Sowié) – heir to the village throne whom we see returning from France – are the two key human agents suggesting the presence of a more cosmopolitan, global masculinity and world.

Examining the film’s symbolic presentation of contrasting forces, Moorman describes four ‘poles’, or ‘towers’, representing different power sources spanning the ancient and the modern.[18]Moorman, op. cit., p. 110. Existing palimpsest-like in the village, spanning substantial historical periods, these are the ant hill, the mosque, the radio pyre and Mercenaire’s stall. The first of these suggests the ancient, the second invokes Islam, the third embodies modern communications and the fourth represents global capitalism at the local level. This last pole may be modest in physical size, but is figuratively immense. Situated just beyond the village square, which Moorman describes as ‘the scene of village conviviality, ritual, justice, debate, and exchange’,[19]ibid. Mercenaire’s cart suggests the ultimate threat to tradition, for now kept violently at bay: global-capitalist modernity, by way of the region’s former colonial power, adding yet another layer to the film’s palimpsestic rendering of space.[20]Mercenaire sells baguettes to the locals and speaks in French to fellow cosmopolitan Ibrahima, who accuses him of exploiting the villagers by selling stale bread at inflated prices. Replying that bread is cheaper than rice or millet, the petit-capitalist adds, ‘You’ve been to Europe; you know what free market and globalisation mean.’ Mercenaire’s name has an additional, related meaning when he describes having been part of an international ‘peacekeeping’ force.

Moorman suggests that the village’s ‘four poles’ are ‘forces with a vertical presence in society, which Sembène represents visually’, defining a tower as

a physical structure that connects heaven and earth, divine and secular power […] Each of the towers in this film also has horizontal reach, rendered diegetically: around the question of the moolaadé, the everyday practices of Islam and their technological mediation, new commodities and price exploitation, and the relationship of the radios and television to NGOs and outside forces.[21]Moorman, op. cit., p. 110.

The poles represent different kinds of contrasting and connected power that, in many respects, Sembène’s political perspective would suggest to be commonly regressive. But their contradictions are useful and generative: once put into conflict, potentially opening the door to more radical destabilisation and change.

So what ultimate vision of such forces – their contradiction and mutual destabilisation upon repeated human resistance ‘from below’ – does Moolaadé provide? Collé becomes a kind of beacon or radio, and thereby an alternative, human and revolutionary ‘pole’, through her rebellion and suffering. A growing number of women cheer her on in the final scene, appearing victorious by film’s end. Her appropriation of space via the moolaadé may have worked to kick off a select form of revolutionary change, at least for now. But while the sclerotic, entirely hypocritical rules of the patriarchs have suffered a blow, a perhaps slightly more liberal-seeming regime will likely rebuild quickly enough. The women would thereby return to their polygynous lives and roles. In fact, while the filmmaker’s critical view of polygamy is well known,[22]See David Murphy, Sembene: Imagining Alternatives in Film & Fiction, 2000, James Currey, Oxford, UK, 2000, p. 142. even this particular patriarchal tradition provides another fascinating case in which the women’s rebellion would have been far less likely to occur without the potential of solidarity – as opposed to intra-family female competition – enabled by an oppressive custom. Tradition is again thereby harnessed, or appropriated, for progressive ends irrespective of its male-authored design and social purpose. Having demonstrated how patriarchal power is always vulnerable to a stealth attack from under its very nose via the domestic and social structures it authors and seemingly controls, the women’s polygamy-aided victory is nonetheless quite likely to give way to a reaffirmed, marginally updated model of patriarchal control no matter the family structure and sexual dictates. The reality of social space’s potential instability cuts both ways.

The wider world is represented at the human level by Mercenaire and Ibrahima, despite the open conflict between the two (at one point, the former accuses the latter and his male relatives of being paedophiles), with both eventually siding with the women’s uprising. Yet the most important ally is the only seemingly inhuman one: technology, via the radios and aerial as well as the spectre of television (Ibrahima brings a set home from France only for his father, the King, to ban it). This ‘virtual’ modern media reality provides the film’s largest, most diffuse, trans-ideological and important spatial dimension, the ‘pole’ against which the elders cannot sustain their fight, no matter how many radios they burn. Despite its worldly, inhuman nature, this modern technological dimension is associated very much with the women. Positing these heavily gendered bodies and technology as crucially integrated in the process of becoming a social force due to the association of the women’s growing power with their access to radio-sourced information, Moorman concludes:

The poles of the square have been disrupted, if not completely rearranged. The ending is both clear and inconclusive: a new order is imminent, even if exactly what form it will take remains to be determined. The particular patriarchal power structure that existed has been struck a powerful blow. And the new high tower, a frame unto itself, is the aerial antenna, both vertical and horizontal at once. The [concluding] song, clearly West African, sonically ties the last scenes together and suggests that this form of media is no less foreign than any other, that its politics will be a question of practice.[23]Moorman, op. cit., pp. 113–4.

We should not expect a longstanding leftist filmmaker to uncritically celebrate the power of mass media, and Moorman’s concluding point is apposite. Sembène does not suggest a simple binary pitting modernity against tradition, as we have seen. Both always need interrogation, their politics an ongoing ‘question of practice’. Moolaadé expertly shows how history – which, for our Marxist filmmaker, must include the present – is always in flux, containing within it the seeds of revolutionary potential while also offering copious ongoing evidence of reactionary control, cobbled together and sustained via ancient and modern means, over human populations.

Collaborative, diffuse agency

Thinking through its multilayered presentation of power, space and agency, Moolaadé emerges less as one woman’s heroic story and more as an expert articulation and summation of Sembène’s particular approach to storytelling and history. The film’s updated cinematic form and mode of political address result in some ‘decoys’ suggesting that individual character psychology and heroic-mythic action – obsessed over by so much Western filmmaking from Hollywood through to mainstream art cinema – does ultimately save the day. On closer inspection, Moolaadé offers an especially stealthy incarnation of Sembène’s distinct, revolutionary brand of political modernism.

To suggest that Collé’s act of asylum kicks off this story of potentially significant historico-political change would be quite inaccurate. Sembène repeatedly shows that progress is brought about not by a single person’s actions, but rather by a series of related events driven by living history. Within the microsociety of a West African village, the spark for rebellion is nothing more than some frightened girls’ intuitive flight from horrible suffering and violence. That this fact is not especially stressed by the film provides a founding example of Sembène’s subtlety and even slyness, demonstrating how the first step towards overcoming reactionary traditions can be easily misidentified, or indeed missed. When Collé is first informed by the now-teenage Amsatou – whom she had previously refused to have cut – why the girls have arrived at the compound, her initial response is far from welcoming. ‘Suspecting bad behaviour on the part of the girls,’ Petty writes, Collé ‘raises the broom she has been sweeping with, but is prevented from disciplining the children when her daughter, Amsatou, points out that, based on their attire, the girls have fled the excision ritual.’[24]Petty, op. cit., p. 332. As herself a literal embodiment of dominant history’s potential subversion, the daughter needs to remind her mother of her own reputation and, thereby, obligation in the form of an expanded ethico-social responsibility.

Not so much intellectual or political, the event leading to Amsatou reminding Collé of her historical actions is the entirely human cause of seeking to avoid suffering, even if that means refusing the enforced dictates of one’s local culture. By asking Collé for protection due to her reputation, the girls implicitly challenge her to develop an enlarged perspective beyond the self-interest of family. In both the origin of their actions and target for asylum, the girls thereby intuitively play out principles long emphasised by leftist analyses of history and progress.

When Collé’s gradual determination later falters, first the eldest wife and then other mothers outside the family take on the mantle, giving the train of events set in motion a thoroughly social momentum. Meanwhile, longstanding historical developments beyond the village are making themselves felt through outside voices – the French-speaking Mercenaire and Ibrahima, who is also French-educated – but also those heard by the women on their radios, by which they learn that female circumcision is not required by Islamic law. Any revolutionary change takes years, decades or sometimes centuries to brew, but its definitive moment can be very swift. Meanwhile, the ‘success’ and meaning of any such development are also never secure. Radical change cannot take place in a vacuum: no single person or even group can bring it about. The film also shows how it does not occur at, or as, some sort of historical ‘ground zero’. Collé’s actions are, thereby, not in the name of secular reason and ‘human rights’ prevailing over tradition and religion (as Western fantasies may often have it). Rather, tradition is invoked as another version of power that appears to secular minds as much (or even more) ‘mumbo jumbo’ as the customised Islam doggedly enforced by the village elders.

A stealthy revolution

Just as the film portrays the cause of revolutionary change as not lying with any kind of singular agency, neither thereby is it shown to require radical newness. Instead, Moolaadé presents history by examining its more palimpsestic, always contradictory dimensions, drawing out revolutionary potential and upending the artificially ordered and (would-be) secure workings of power presumed to operate under the stable thumb and heel of reactionary men. With multiple sites and spaces playing their concurrent role in Sembène’s thoroughly cinematic, ‘presentational’ version of theatricalised space, the magical ability of some colourful yet prosaic rope draped across an open clay doorway shows the importance of metaphysics and power – hardly differentiable, as they are – to how we understand and see space, and the way space can be appropriated and thereby remade by what appears on the surface to be the simplest change and rearticulation. What becomes of such an act – an appropriation of normally conservative, supposedly unchanging space and tradition – is, however, never predictable.

Moolaadé appears to conclude with the positive portrayal of a chain of events spanning the local to the global, playing out within a few hundred square metres. However, while conservative social forces may be sclerotic, when provoked into a defensive posture they can easily be reborn in a more nimble form in the interests of maintaining power. The patriarchally mandated religious imprimatur to mutilate women’s bodies that Collé and some of the women seem to have succeeded in destroying by the film’s end was itself sustained through the selective application of Islamic law and the hiding of contradiction beneath the performative illusion of stability and coherence. There is no guaranteeing that the forces of reaction will not once more master their traditional art through a stealth comparable to that demonstrated by women in this film. Nevertheless, Moolaadé demonstrates with forensic skill and real force that, no matter how seemingly entrenched, power is always vulnerable to solidarity. Just as importantly, it shows how the palimpsestic history and space that such power tries so hard to pretend is surer ground in fact offers real potential for the status quo’s material overthrow, via a combination of historical forces set in train – no matter how little agency and revolutionary intention any such rebellion’s human initiators may initially exhibit.

This article has been refereed.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Sheila Whitaker, ‘Ousmane Sembène’, The Guardian, 12 June 2007, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/jun/11/obituaries>, accessed 27 May 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Louis Ndong, ‘The Use of Languages as Linguistic Militancy in Ousmane Sembène’s Films: Between Film Aesthetics and Cinematographic Reception’, African Renaissance, vol. 14, no. 3/4, September–December 2017, p. 59. Emphasis added. |

| 3 | Jude G Akudinobi, ‘Durable Dreams: Dissent, Critique, and Creativity in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé’, Meridians, vol. 6, no. 2, 2006, p. 177. |

| 4 | Marissa J Moorman, ‘Radio Remediated: Sissako’s Life on Earth and Sembène’s Moolaadé’, Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, Fall 2017, pp. 111–2. Emphasis removed. |

| 5 | See Jen Westmoreland Bouchard, ‘Portrait of a Contemporary Griot: Orality in the Films and Novels of Ousmane Sembène’, The Journal of African Literature, no. 6, 2009. |

| 6 | Samba Diop, ‘Music and Narrative in Five Films by Ousmane Sembène’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 1, no. 2, 2009, p. 208. |

| 7 | Ndong, op. cit., p. 59. |

| 8 | Akudinobi, op. cit., p. 177. |

| 9 | Akudinobi cites an Australian review, whose title – ‘Roping Out the Horrors of the Past’ – demonstrates the problem of Western responses that maintain a binary understanding of history, as an example of ‘the hermeneutic dangers that African films and institutions face as they traverse global cultural zones’. See ibid., p. 188. |

| 10 | Ousmane Sembène, quoted in Jacqueline Fitzgerald, ‘Stand Against Genital Mutilation’, Chicago Tribune, 1 December 2004, <https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2004-12-01-0412010043-story.html>, accessed 27 May 2020. |

| 11 | Dominica Dipio, ‘Gender Wars Around Religion and Tradition in Sembène Ousmane’s Moolaadé’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010, pp. 128–9. |

| 12 | Rosemary Chikafa-Chipiro, ‘The Representation of African Womanhood in Sembène’s Moolaadé: An Africana Womanist Reading’, Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 9, no. 2/3, 2017, p. 251. |

| 13 | Dipio, op. cit., p. 125. |

| 14 | Sheila Petty, ‘Postcolonial Transformations: From Emitaï (Sembène 1971) to Moolaadé (Sembène 2004)’, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 2011, p. 332. |

| 15 | Dipio, op. cit., p. 131. |

| 16 | Chikafa-Chipiro, op. cit., p. 249. |

| 17 | ibid., p. 256. |

| 18 | Moorman, op. cit., p. 110. |

| 19 | ibid. |

| 20 | Mercenaire sells baguettes to the locals and speaks in French to fellow cosmopolitan Ibrahima, who accuses him of exploiting the villagers by selling stale bread at inflated prices. Replying that bread is cheaper than rice or millet, the petit-capitalist adds, ‘You’ve been to Europe; you know what free market and globalisation mean.’ |

| 21 | Moorman, op. cit., p. 110. |

| 22 | See David Murphy, Sembene: Imagining Alternatives in Film & Fiction, 2000, James Currey, Oxford, UK, 2000, p. 142. |

| 23 | Moorman, op. cit., pp. 113–4. |

| 24 | Petty, op. cit., p. 332. |