Who was that other fellow, and why doesn’t he speak English?[1]Spoken by Bernie (Bill Levis) in Episode 3 of The Stranger.

One of the more exciting releases for Australian cultural and television historians appeared relatively quietly on YouTube and ABC iview in early 2020: the 1964–1965 Australian science fiction TV serial The Stranger. Unavailable for decades, the series was restored by the ABC’s RetroFocus project (co-founded by Jon Steiner and Helen Meany) and the ABC Archives team,[2]See Dannielle Maguire & Bridget Judd, ‘The Stranger, Australia’s Answer to Doctor Who, Premieres on ABC iview After Decades in the Vaults’, ABC News, 2 Feb 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-02/abc-iview-to-stream-the-stranger-australian-dr-who/11870424>; ‘Backstory: RetroFocus Unearths Historical Footage in ABC’s Rich Archive to Share with a New Audience’, ABC News, updated 18 May 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/redirects/backstory/2018-07-26/retrofocus-shares-abc-archive-with-digital-audience/10037720>; and Natasha Johnson, ‘How Remastering ABC TV Show The Stranger After 55 Years Brought Joy to Its Star, Ron Haddrick, in His Dying Days’, ABC News, 17 May 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/redirects/backstory/2020-05-17/abc-iview-the-stranger-brings-joy-to-dying-star-ron-haddrick/12243876>, all accessed 16 November 2021. providing an all-too-rare opportunity to experience a piece of Australia’s early television history – a history that, for a range of reasons, still remains largely ephemeral, invisible and neglected. For that reason alone, the difficult work done to make The Stranger available is of undeniable cultural importance and value. While its importance has been primarily framed in relation to its genre and production context, the series also provides an opportunity to reflect on Australia’s role in relation to refugees and international politics, both then and now.

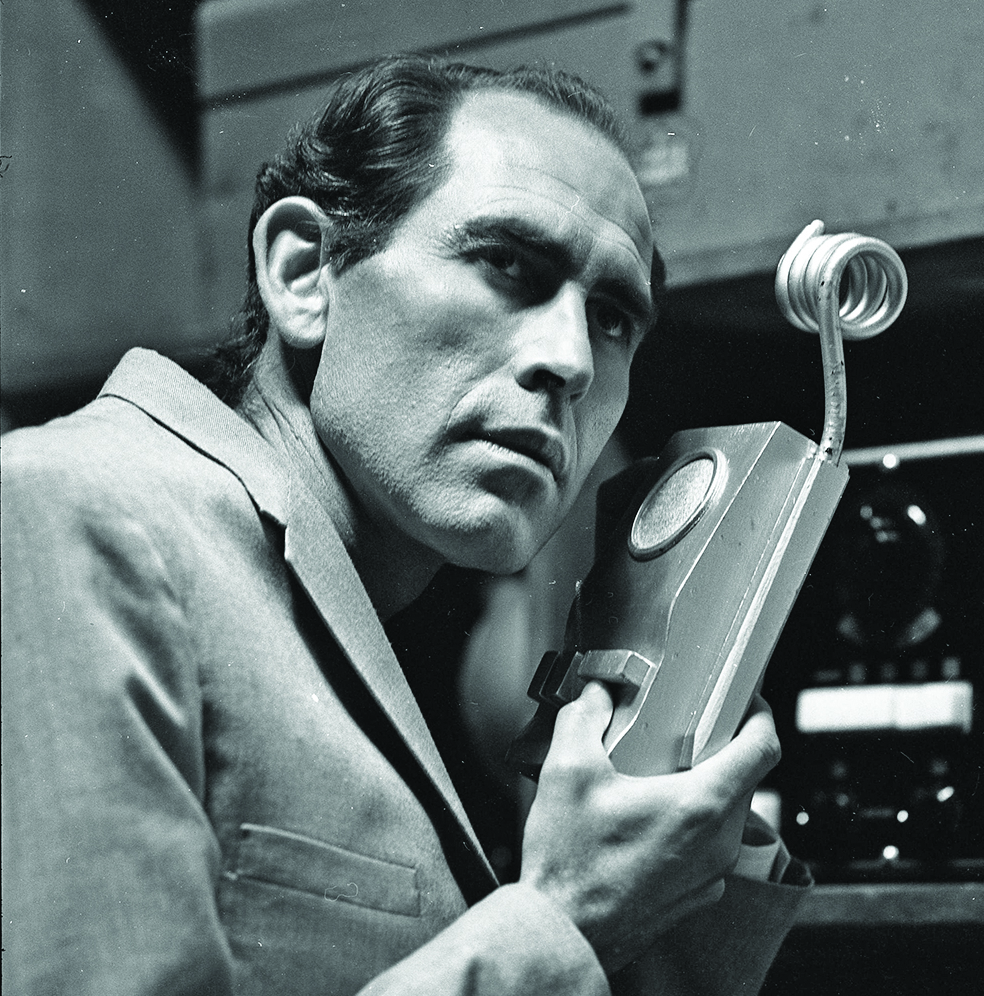

The Stranger’s initial tone is one of mystery and uncertainty. A clap of thunder introduces a rain-drenched suburban Sydney street where a ‘no through traffic’ sign can be glimpsed in the light of sporadic lightning flashes (a fleeting frame-edge detail likely barely visible in the original broadcast). A hand reaches into the frame as though feeling the falling rain, its counterpart then entering the frame to delicately touch the wet palm. The hands belong to a tall, focused man (Ron Haddrick) drenched by the rain, who enters the gate of a house marked ‘Headmaster: St. Michael’s School for Boys’. Arriving at the front door, he calmly lies on his back on the front steps, reaches behind him, knocks and, seemingly satisfied, shuts his eyes and waits. The scene fades to the opening credits shot of the Parkes radio telescope in New South Wales, followed by some brief outer-space imagery, linking the ominous noir-like suburban scene taking place down here with unknown mysteries taking place somewhere out there.

‘You can’t fool them’

At the time of its airing, discussion of The Stranger and its relevance focused strongly on its supposed connections to scientific feasibility and location filming along with its production context, perhaps suggesting a level of discomfort with science fiction as a genre and a vehicle for social commentary. While reportedly developing an adult following[3]‘The Stranger Has Visited Canberra’, The Canberra Times, 19 October 1964, p. 17, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/131755571>, accessed 1 October 2021. and being described as ‘one of the ABC’s top-rating serials’,[4]‘He’s No Stranger to Us Now’, TV Week (Adelaide), 3 July 1965, p. 10. the series is overtly positioned in contemporaneous news articles as being targeted at children and a level of childhood ‘sophistication’; accordingly, the initial coverage of The Stranger focused strongly on ideas of accuracy and believability. For instance, the series is presented in Adelaide’s TV Week of 25 April 1964 as ‘a S-F thriller for young ’uns’, with the focus on accuracy being directly linked to the notion that ‘young viewers have become sophisticated’: the article goes on to note that ‘producer Storry Walton, and designer Geoffrey Wedlock, took great care to check the accuracy of the production’, including having the design of the series’ spaceship ‘checked by the CSIRO’.[5]‘The Stranger: A S-F Thriller for Young ’Uns’, TV Week (Adelaide), 25 April 1964, p. 20.

In the 29 April 1964 edition of The Australian Women’s Weekly, Nan Musgrove offers a similar view in an article titled ‘KIDS! – You Can’t Fool Them’, also noting the CSIRO’s involvement as well as that the spaceship design had been ‘sent to be checked by a leading engineering firm’.[6]Nan Musgrove, ‘KIDS! – You Can’t Fool Them’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 29 April 1964, p. 15, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/51775573>, accessed 1 October 2021. Producer Walton is quoted suggesting that

children and young teenagers are so sophisticated these days that anything presented to them has to be scientifically feasible. It cannot be entirely imaginative, entirely Buck Rogers. It has to have a broad and sound basis of known scientific fact.[7]Storry Walton, quoted in Musgrove, ibid.

Along with scientific feasibility, Musgrove also indicates the ‘attention to detail’ that ‘gives great meaning to that important phrase “a good production”’, noting the use of location filming in Sydney settings such as St. Paul’s College, Hunters Hill and the suburban railway station of Berowra.[8]Musgrove, ibid. A 1964 TV Times article similarly emphasises the location specifics of filming and Walton’s focus on feasibility: ‘I feel children know quite a bit about such things, so we had to have something that looked scientifically correct and was feasible aerodynamically.’[9]Storry Walton, cited in Johnson, op. cit.

Just as the early commentary on The Stranger seems to have largely taken its lead from Walton’s focus on sophistication and feasibility (traits also associated with the work of series writer GK Saunders[10]See ‘G. K. Saunders’, Austlit, updated 10 October 2012, <https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/A15456>, accessed 1 October 2021.), ABC materials associated with the 2020 rerelease maintain this emphasis. A discussion about Saunders’ work on the series is introduced with the subheading ‘More realism than Doctor Who’,[11]Maguire & Judd, op. cit. William Hartnell, who played the Doctor in Doctor Who from 1963 to 1966, was quoted in Adelaide’s 8 May 1965 edition of TV Week with a somewhat different framing of the genre’s relation to feasibility: ‘I am hypnotised by Dr. Who, myself […] When I look at a script I find it unbelievable. So I allow myself to be hypnotised by it. Otherwise I would have nothing to do with it.’ Hartnell, quoted in ‘He Hypnotises Himself’, TV Week (Adelaide), 8 May 1965, p. 31. and similarly quotes Walton: ‘What we had going for us is that we used real people and entirely plausible ideas.’[12]Storry Walton, quoted in Maguire & Judd, ibid. In another ABC News article, archivist Steiner emphasises the show’s ‘quite […] sophisticated and complex story’.[13]Jon Steiner, quoted in Johnson, op. cit.

The cultural importance of The Stranger is also asserted in relation to the 2020 rerelease through its description as ‘Australia’s first locally-produced science fiction television show and one of the first Australian series to be sold overseas’[14]Maguire & Judd, op. cit. – although ‘television show’ is perhaps a slightly misleading rewording of the more specific ‘television series’ in an otherwise near-identical passage in Tammy Burnstock’s curator’s notes on the series on australianscreen,[15]Tammy Burnstock, ‘Curator’s notes’, ‘The Stranger – Series 1 Episode 1’, australianscreen,<https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/the-stranger-episode-1/notes/>, accessed 1 October 2021. The page is undated, but it appears to have been published prior to the 2020 rerelease. while the aforementioned 1964 TV Times article refers to The Stranger as ‘our first space serial’.[16]Cited in Johnson, op. cit.

The idea of ‘firsts’ can often require some quibbling and contextualisation, even when technically correct. The Stranger, at any rate, certainly wasn’t the first intersection between Australian television and science fiction, and what’s potentially significant in a production context isn’t necessarily notable for actual viewers, then or now. The Adelaide TV Week summary, for example, isn’t particularly beguiled by the science fiction element, introducing the series as ‘more science fiction on ABS2’ and observing that ‘so many films and TV shows are devoted to space travel and science’.[17]‘The Stranger: A S-F Thriller for Young ’Uns’, op. cit.

One such show was the children’s TV series Mr. Squiggle – making its debut in 1959 – whose titular character is labelled in a clip on australianscreen as ‘Australia’s first astronaut’,[18]‘Mr Squiggle and Friends – Episode 148 (c.1960)’, australianscreen,<https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/mr-squiggle-episode-148/>, accessed 1 October 2021. although that’s perhaps stretching the comparison a little. More pertinently, Stephen Vagg writes that the Australian-produced TV film The Astronauts (Christopher Muir, 1960) was ‘broadcast live from the ABC’s studios at Ripponlea’ and ‘later purchased for screening in the USA on the CBS network’, with local promotional advertisements referring to it as the ‘first live TV play on space travel’; Vagg goes on to note similar locally produced broadcasts such as The End Begins (Ray Rigby, 1961), The Road (Patrick Barton, 1964) and Campaign for One (Brian Faull, 1965).[19]Stephen Vagg, ‘Forgotten Australian TV plays: The Astronauts’, FilmInk, 11 July 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/forgotten-australian-tv-plays-the-astronauts/>, accessed 1 October 2021. Even earlier, Tomorrow’s Child (John Coates, 1957), a ‘satirical comedy of the future’,[20]Advertisement, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 April 1957, p. 7. is described in The A.B.C. Weekly as ‘the first hour-length “live” play on Channel 2’.[21]‘Looking Ahead on Channel 2 (ABN)’, The A.B.C. Weekly, vol. 19, no. 18, 4 May 1957, p. 33, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1499738178/view?partId=nla.obj-1499927237#page/n32/mode/1up>; see also ‘Tomorrow’s Child (9 April 1957)’ Australian TV Plays, <https://australiantvplays.blogspot.com/p/tomorrows-child-9-april-1957.html>, both accessed 1 October 2021. Whatever the accuracy of the claim that The Stranger was the country’s first small-screen sci-fi work – or debates over what exactly constitutes a ‘television show’ – what’s clear is that, at this time, science fiction TV was varied and well established overseas,[22]See, for example, Jonathan Bignell, ‘Space for “Quality”: Negotiating with the Daleks’, in Bignell & Stephen Lacey (eds), Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2005, p. 77. and Australian screens in the 1960s were full of imported US and UK material.[23]A June 1964 issue of TV Week notes that ‘if the audience reaction is favorable, ADS7 will screen […] sci-fi movies in a regular program entitled Science Fiction Theatre’. Tom McKain, ‘Sci-fi Segment Screened on Seven’, TV Week (Adelaide), 27 June 1964, p. 24.

‘Do you come from Europe?’

While all of these points are undeniably important in terms of understanding The Stranger’s place within Australia’s TV and cultural history, perhaps the most potent element of The Stranger – and one that maintains strong currency in both its original and rerelease contexts – is its fairly overt thematic focus on the topic of refugees and migrants.

This is not an uncommon theme for science fiction stories, of course, with strange and benevolent visitors from other places often coming into conflict with local norms, rules and authorities. But how The Stranger engages – simultaneously indirectly and overtly – with these ideas in a specifically Australian context, and in the context of Australia in the early 1960s, is perhaps a stronger marker of what the series can offer to a modern cultural discussion.[24]Maguire and Judd briefly note this connection: ‘[The Stranger] also brings up the issue of how society should treat refugees.’ Maguire & Judd, op. cit.

Genre texts are, of course, long established as being as notable for their underlying connections and concerns as their more fantastical or prophetic elements; as Patrick Parrinder puts it, ‘[Brian] Aldiss and [Ursula K] Le Guin, among others, have frequently asserted that the genre’s portrayal of the future of space travel, alternative Societies and alternative life-forms is at bottom metaphorical.’[25]Patrick Parrinder, ‘Science Fiction: Metaphor, Myth or Prophecy?’, in Karen Sayer & John Moore (eds), Science Fiction, Critical Frontiers, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2000, p. 27. This can also contribute to positioning a text like The Stranger within the broader context of the work and approach of writer Saunders and other key Australian film and television figures in producer Walton and director Gil Brealey. Brealey was later, in his obituary, described by Walton as having had a ‘belief that film was not only for entertainment but also an instrument of enlightenment and a way to better understand the human condition’.[26]Storry Walton, ‘Film Director Lifted Australian Cinema out of Stagnation’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/gil-brealey-obituary-australian-film-picnic-20180425-p4zbk7.html>, accessed 11 October 2021.

The Stranger quickly establishes ethnicity as a key focus for interrogating the idea of alien difference. After Haddrick’s initially unnamed character staggers into the suburban Sydney house in Episode 1 and presents himself as being without memory, his background and accent are the first points of reference: ‘Well, at least we can tell from your speech that you’re not Australian-born. Do you come from Europe?’ (‘Yes, perhaps,’ he replies.)

He is revealed as multilingual, and speaks English in a somewhat stilted manner with a heavy accent. When he adopts a name, Adam Suisse, his new surname is drawn from attempts to pinpoint exactly where in Europe he might be from (as for his first name, he reasons, ‘I cannot remember past happenings, so I am a new man, no? And the name for a new man, it is Adam’). When, in Episode 3, teenagers Bernie (Bill Levis), Jean (Janice Dinnen) and Peter (Michael Thomas) follow Adam to his ship in the mountains and find him with a companion and a spaceship, the question is still one of basic Earthbound cultural differences: ‘Who was that other fellow, and why doesn’t he speak English?’

‘Their leader – she’s a woman’

Establishing whether or not The Stranger – or any media text – can be said to have or present a particularly coherent view of the cultural tensions of its time is fraught with difficulties. Nevertheless, within the limitations of a format that prioritises an ongoing series of tensions and looming threats over polemic, The Stranger appears to favour the welcoming of migrants and refugees, along with Australia maintaining a strong voice on the global stage. Certainly, the young characters who serve as the show’s focal point (particularly in the first season) are consistently supportive of Adam’s inclusion, quick to learn and eager to support the wandering people of the planet Soshuniss; they’re alert to variation from their cultural expectations, but also immediately receptive to engagement. For instance, when they meet the first Soshun (Mary Mackay) – the elected leader of Soshuniss’ people – Bernie rushes to Peter to holler, ‘It’s a woman, Peter! The Soshun’s a woman!’.

Within the limitations of a format that prioritises an ongoing series of tensions and looming threats over polemic, The Stranger appears to favour the welcoming of migrants and refugees, along with Australia maintaining a strong voice on the global stage.

Moments later, they’re introducing themselves in the awkwardly hopeful way that well-meaning strangers might try out a new language, with pleasant laughter all around at the effort. The Stranger doesn’t have much opportunity to develop the planet’s culture beyond a few brief and unremarkable theatrics, but the sequence of the children on Soshuniss is primarily one of embracing new cultural mundanities rather than a suggestion of a shocking or confronting difference to be negotiated. When Jean refers to the Soshun’s gender in the following episode, it’s somewhat more calmly (‘Their leader – she’s a woman’), although there is little focus on female characters after this (and the Soshun soon makes way for a male successor).

The series’ casual negotiation of cultural variance perhaps also suggests the ease of its disappearance. After acknowledging and politely negotiating language differences, the Soshun makes it clear that she can speak English (‘You wonder that I speak your language?’; ‘Well, yes … no … well, I mean, yes.’) and has studied ‘many of [their] books’. The Soshun’s following speech to the children, which establishes her people’s underlying goal as the narrative unfolds, fits in closely with the then-prevailing policy in Australia of ‘assimilation’, in which, in the words of sociology professor Andrew Jakubowicz, ‘migrants were to become “Australian” as quickly as possible, with limited assistance from the Government’:[27]Andrew Jakubowicz, ‘Commentary on: Welcoming New Migrants as New Australians’, Making Multicultural Australia website, <http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/library/media/Timeline-Commentary/id/11.Welcoming-new-migrants-as-New-Australians>, accessed 1 October 2021.

We are good people, not ignorant people […] When we live with you on your planet, all our knowledge is your knowledge. We will share all things, teach each other many things. We have wandered in space many generations – this is not possible forever. Before I die, I wish my people to live on a friendly, beautiful planet as they were intended by nature.

The Soshun’s speech is clear on the idea of shared benefit within a pre-existing and idealised Australian context; after the children leave, she continues: ‘My people, I wish you all to study the English language very carefully – because I believe the great event that we have been preparing for is very close.’

This focus on reciprocal benefit broadly aligns the Soshun’s attitude with the ideal of the European migrant as defined by Australia’s 1950s and early 1960s Good Neighbour movement. As Jakubowicz summarises it, this emphasised ‘helping immigrants to learn English, encouraging schools to aid in assimilating migrant youth and encouraging all migrants to become naturalised’, along with ‘some recognition that immigration was a two-way opportunity’: that ‘“older” Australians could learn from new migrants as well as teach them, and migrants should be recognised for their contribution to the development of the Australian economy’.[28]ibid. The Commonwealth Department of Immigration’s guide to the Good Neighbour movement described assimilation as:

a process of give and take – a two-way process […] It requires Australians to offer the hand of friendship and to make allowances for differences in mannerisms or accent of the newly arrived. It requires the newcomers to try to learn and appreciate the customs and traditions of their new homeland and to live in harmony with themselves and with their new fellow citizens.[29]Commonwealth Department of Immigration, A Handbook of the Good Neighbour Movement: To Assist People Interested in the Assimilation of Migrants, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52847074/view?partId=nla.obj-101243931>, accessed 1 October 2021.

Politics researcher Gwenda Tavan argues that this approach ‘indicated anxiety about the pace of economic and social change in the postwar period’ and a ‘desire to preserve the “British–white” identity and social–liberal values that had traditionally defined Australian social life’, but that it ultimately ‘proved untenable’.[30]Gwenda Tavan, ‘“Good Neighbours”: Community Organisations, Migrant Assimilation and Australian Society and Culture, 1950–1961’, Australian Historical Studies, 1997, vol. 27, no. 109, 1997, p. 77.

‘The Soshun of Australia’

As the cluttered interests of the adult world take over, The Stranger moves from its initial science fiction premise – a broad children’s investigation adventure with a mysterious ‘foreigner’ – through stages of media-related chaos, international tensions with United Nations involvement, and strategy changes brought about by a new Soshun and a more assertive regime. Ultimately, the series’ narrative revolves around the danger posed by corporate machinations attempting to bypass the authority of individual nations, the oversight of the United Nations and the idea of a benevolent scientific approach.

It’s particularly interesting to see an Australian narrative positioning Australia on the global stage, with locations like Canberra and Parkes central to global discussions. While the famous remark often attributed to actor Ava Gardner that Australia was the perfect place to make a film about the end of the world was fabricated,[31]See Adrian Danks, ‘“There Is Still Time … Brother”: On the Beach and Lawrence Johnston’s Fallout’, Senses of Cinema, no. 61, July 2013, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/uncategorized/there-is-still-time-brother-on-the-beach-and-lawrence-johnstons-fallout/>; and Chris Flynn, ‘The Australian Book You’ve Finally Got Time For: On the Beach by Nevil Shute’, The Guardian, 21 May 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/21/the-australian-book-youve-finally-got-time-for-on-the-beach-by-nevil-shute>, both accessed 1 October 2021. it was nonetheless a commonplace sentiment at the time; in a 1965 TV documentary about Australians living in London, expat journalist Phillip Knightley confides, ‘At the moment Sydney is still on the periphery of international news […] Each time I go there I feel that the world’s passing me by.’[32]Phillip Knightley, in The Australian Londoners (Stefan Sargent, 1965), cited in Pat Laughren, ‘The 1960s Down Under: Television, Documentary and the “New Nationalism”’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2010, p. 374.

Certainly, then, as now, Australia remained in something of a stand-off with the rest of the world in relation to migration. A letter from the 2 January 1960 edition of Melbourne’s The Age from Kelvin A Mather expresses concern over an approach that he feels is intended to ‘squeeze out the less desirable aliens of this world’:

Long have I grown angry at, what appears to me, the self-righteousness and unreasonableness of many Australians regarding what are considered the necessary qualifications for a migrant to settle in this fair land […] Since when have British peoples been more deserving than many others […]? Meanwhile, the United Nations continues to paint a depressing picture of the growing needs of many underprivileged men, women and children throughout the world.[33]Kelvin A Mather, ‘Tolerance in Migration’, letter to the editor, The Age, 2 January 1960, p. 2.

The concern over the ‘necessary qualifications’ referred to in this letter had long been established in Australia; at the time of The Stranger’s production, the White Australia Policy was still in place.

The Stranger, somewhat hopefully, places a solution to some of these international cultural tensions inside the Australian prime minister’s office: quite literally, in fact, with some key final scenes being filmed in the office of then–prime minister Robert Menzies.[34]Maguire & Judd, op. cit. The prime minister of the series (played by Chips Rafferty), or ‘Soshun of Australia’, not only intervenes to end a global stand-off with asylum seekers from space, but also confronts big-money interests to make sure that the Soshuniss refugees are provided with their own land, free from corporate control and ownership.

While The Stranger’s representation of migration may indicate an idealised vision of White Australia Policy–era assimilation programs, connecting fictional media with real cultural contexts[35]See, for example, Russell Marks, ‘The Left and Australian Nationalism Since the 1960s: A History of Rejection and Ambivalence’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2019, pp. 145–59; and Tavan, op. cit. is an unavoidably complex discussion. The recent reintroduction of The Stranger presents an opportunity to consider the series more closely in relation to the changes in Australian policy from assimilation through ‘integration’ (in the 1960s) to ‘multiculturalism’ (in the 1970s)[36]See Bruce Pennay, ‘Beautiful Balts: From Displaced Persons to New Australians [Book Review]’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 104, no. 1, June 2018, p. 111. – what Tavan describes as the country’s eventual ‘shift from a “British–white”, monocultural definition of the nation to one conceptualised in pluralistic and multicultural terms’.[37]Tavan, op. cit., p. 98. Engagement with this topic cannot, of course, be achieved simply through analysing a single media text, or without considering the exclusions facing non-European migrants and the lingering ‘spirit of White Australia’[38]Matthew Jordan, ‘“Not on Your Life”: Cabinet and Liberalisation of the White Australia Policy, 1964–67’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, p. 195. even after reforms – along with, in law professor Irene Watson’s words, the ‘effects of state protectionist and assimilationist policies instituted in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’[39]Irene Watson, Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law, Routledge, Abingdon, UK & New York, 2014, p. 57. and ‘the phenomenon of colonialism and the impact it has had upon Indigenous Peoples’ lives, laws and territories’ in Australia and around the world.[40]ibid., p. 1.

However we understand The Stranger’s representation of migration today, Australia’s ongoing reluctance to support refugees,[41]See Tom Lowrey, ‘How Many Afghan Refugees Is Australia Taking? Are We Going to Expand Our Refugee Intake?’, ABC News, 19 August 2021, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-19/afghan-refugee-intake-australia-humanitarian-visa-taliban/100388678>, accessed 1 October 2021. the condemnation the country has received on the global stage,[42]See Tom Stayner, ‘UN Condemns Australia’s “Discriminatory” Restrictions Preventing Refugees Reuniting with Family’, SBS News, 21 May 2021, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/un-condemns-australia-s-discriminatory-restrictions-preventing-refugees-reuniting-with-family/24bedcab-0370-4527-897f-91d48c6a102a>, accessed 1 October 2021. its extraordinary payments to corporate entities to imprison asylum seekers[43]See Jane McAdam, ‘Secrecy over Paladin’s $423 Million Contract Highlights Our Broken Refugee System’, The Conversation, 18 June 2019, <https://theconversation.com/secrecy-over-paladins-423-million-contract-highlights-our-broken-refugee-system-118996>; and Sharon Labi, ‘Aussie Taxpayers Funding Multi-billion-dollar Detention Centre Bill’, 9News, 27 July 2020, <https://www.9news.com.au/national/australia-detention-taxpayer-costs-serco-parliamentary-inquiry-figures-politics-news/c90d7552-0a83-4ad4-84c6-4ce6fd1366be>, both accessed 1 October 2021. and its cruelty towards the vulnerable[44]See Ben Doherty, ‘Three Members of Biloela Family Granted Year-long Visas but They’ll Have to Remain in Perth’, The Guardian, 23 September 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/sep/23/three-members-of-biloela-family-granted-year-long-visas-but-theyll-have-to-remain-in-perth>, accessed 1 October 2021. are just a few of the realities that make the series’ representation of Australia as any kind of powerful international citizen and leader its most painfully unfeasible fantasy.

This article has been refereed.

Endnotes

| 1 | Spoken by Bernie (Bill Levis) in Episode 3 of The Stranger. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Dannielle Maguire & Bridget Judd, ‘The Stranger, Australia’s Answer to Doctor Who, Premieres on ABC iview After Decades in the Vaults’, ABC News, 2 Feb 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-02/abc-iview-to-stream-the-stranger-australian-dr-who/11870424>; ‘Backstory: RetroFocus Unearths Historical Footage in ABC’s Rich Archive to Share with a New Audience’, ABC News, updated 18 May 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/redirects/backstory/2018-07-26/retrofocus-shares-abc-archive-with-digital-audience/10037720>; and Natasha Johnson, ‘How Remastering ABC TV Show The Stranger After 55 Years Brought Joy to Its Star, Ron Haddrick, in His Dying Days’, ABC News, 17 May 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/redirects/backstory/2020-05-17/abc-iview-the-stranger-brings-joy-to-dying-star-ron-haddrick/12243876>, all accessed 16 November 2021. |

| 3 | ‘The Stranger Has Visited Canberra’, The Canberra Times, 19 October 1964, p. 17, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/131755571>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 4 | ‘He’s No Stranger to Us Now’, TV Week (Adelaide), 3 July 1965, p. 10. |

| 5 | ‘The Stranger: A S-F Thriller for Young ’Uns’, TV Week (Adelaide), 25 April 1964, p. 20. |

| 6 | Nan Musgrove, ‘KIDS! – You Can’t Fool Them’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 29 April 1964, p. 15, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/51775573>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 7 | Storry Walton, quoted in Musgrove, ibid. |

| 8 | Musgrove, ibid. |

| 9 | Storry Walton, cited in Johnson, op. cit. |

| 10 | See ‘G. K. Saunders’, Austlit, updated 10 October 2012, <https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/A15456>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 11 | Maguire & Judd, op. cit. William Hartnell, who played the Doctor in Doctor Who from 1963 to 1966, was quoted in Adelaide’s 8 May 1965 edition of TV Week with a somewhat different framing of the genre’s relation to feasibility: ‘I am hypnotised by Dr. Who, myself […] When I look at a script I find it unbelievable. So I allow myself to be hypnotised by it. Otherwise I would have nothing to do with it.’ Hartnell, quoted in ‘He Hypnotises Himself’, TV Week (Adelaide), 8 May 1965, p. 31. |

| 12 | Storry Walton, quoted in Maguire & Judd, ibid. |

| 13 | Jon Steiner, quoted in Johnson, op. cit. |

| 14 | Maguire & Judd, op. cit. |

| 15 | Tammy Burnstock, ‘Curator’s notes’, ‘The Stranger – Series 1 Episode 1’, australianscreen,<https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/the-stranger-episode-1/notes/>, accessed 1 October 2021. The page is undated, but it appears to have been published prior to the 2020 rerelease. |

| 16 | Cited in Johnson, op. cit. |

| 17 | ‘The Stranger: A S-F Thriller for Young ’Uns’, op. cit. |

| 18 | ‘Mr Squiggle and Friends – Episode 148 (c.1960)’, australianscreen,<https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/mr-squiggle-episode-148/>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 19 | Stephen Vagg, ‘Forgotten Australian TV plays: The Astronauts’, FilmInk, 11 July 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/forgotten-australian-tv-plays-the-astronauts/>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 20 | Advertisement, The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 April 1957, p. 7. |

| 21 | ‘Looking Ahead on Channel 2 (ABN)’, The A.B.C. Weekly, vol. 19, no. 18, 4 May 1957, p. 33, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1499738178/view?partId=nla.obj-1499927237#page/n32/mode/1up>; see also ‘Tomorrow’s Child (9 April 1957)’ Australian TV Plays, <https://australiantvplays.blogspot.com/p/tomorrows-child-9-april-1957.html>, both accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 22 | See, for example, Jonathan Bignell, ‘Space for “Quality”: Negotiating with the Daleks’, in Bignell & Stephen Lacey (eds), Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2005, p. 77. |

| 23 | A June 1964 issue of TV Week notes that ‘if the audience reaction is favorable, ADS7 will screen […] sci-fi movies in a regular program entitled Science Fiction Theatre’. Tom McKain, ‘Sci-fi Segment Screened on Seven’, TV Week (Adelaide), 27 June 1964, p. 24. |

| 24 | Maguire and Judd briefly note this connection: ‘[The Stranger] also brings up the issue of how society should treat refugees.’ Maguire & Judd, op. cit. |

| 25 | Patrick Parrinder, ‘Science Fiction: Metaphor, Myth or Prophecy?’, in Karen Sayer & John Moore (eds), Science Fiction, Critical Frontiers, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2000, p. 27. |

| 26 | Storry Walton, ‘Film Director Lifted Australian Cinema out of Stagnation’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/gil-brealey-obituary-australian-film-picnic-20180425-p4zbk7.html>, accessed 11 October 2021. |

| 27 | Andrew Jakubowicz, ‘Commentary on: Welcoming New Migrants as New Australians’, Making Multicultural Australia website, <http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/library/media/Timeline-Commentary/id/11.Welcoming-new-migrants-as-New-Australians>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 28 | ibid. |

| 29 | Commonwealth Department of Immigration, A Handbook of the Good Neighbour Movement: To Assist People Interested in the Assimilation of Migrants, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52847074/view?partId=nla.obj-101243931>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 30 | Gwenda Tavan, ‘“Good Neighbours”: Community Organisations, Migrant Assimilation and Australian Society and Culture, 1950–1961’, Australian Historical Studies, 1997, vol. 27, no. 109, 1997, p. 77. |

| 31 | See Adrian Danks, ‘“There Is Still Time … Brother”: On the Beach and Lawrence Johnston’s Fallout’, Senses of Cinema, no. 61, July 2013, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/uncategorized/there-is-still-time-brother-on-the-beach-and-lawrence-johnstons-fallout/>; and Chris Flynn, ‘The Australian Book You’ve Finally Got Time For: On the Beach by Nevil Shute’, The Guardian, 21 May 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/21/the-australian-book-youve-finally-got-time-for-on-the-beach-by-nevil-shute>, both accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 32 | Phillip Knightley, in The Australian Londoners (Stefan Sargent, 1965), cited in Pat Laughren, ‘The 1960s Down Under: Television, Documentary and the “New Nationalism”’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2010, p. 374. |

| 33 | Kelvin A Mather, ‘Tolerance in Migration’, letter to the editor, The Age, 2 January 1960, p. 2. |

| 34 | Maguire & Judd, op. cit. |

| 35 | See, for example, Russell Marks, ‘The Left and Australian Nationalism Since the 1960s: A History of Rejection and Ambivalence’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2019, pp. 145–59; and Tavan, op. cit. |

| 36 | See Bruce Pennay, ‘Beautiful Balts: From Displaced Persons to New Australians [Book Review]’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 104, no. 1, June 2018, p. 111. |

| 37 | Tavan, op. cit., p. 98. |

| 38 | Matthew Jordan, ‘“Not on Your Life”: Cabinet and Liberalisation of the White Australia Policy, 1964–67’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, p. 195. |

| 39 | Irene Watson, Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law, Routledge, Abingdon, UK & New York, 2014, p. 57. |

| 40 | ibid., p. 1. |

| 41 | See Tom Lowrey, ‘How Many Afghan Refugees Is Australia Taking? Are We Going to Expand Our Refugee Intake?’, ABC News, 19 August 2021, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-19/afghan-refugee-intake-australia-humanitarian-visa-taliban/100388678>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 42 | See Tom Stayner, ‘UN Condemns Australia’s “Discriminatory” Restrictions Preventing Refugees Reuniting with Family’, SBS News, 21 May 2021, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/un-condemns-australia-s-discriminatory-restrictions-preventing-refugees-reuniting-with-family/24bedcab-0370-4527-897f-91d48c6a102a>, accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 43 | See Jane McAdam, ‘Secrecy over Paladin’s $423 Million Contract Highlights Our Broken Refugee System’, The Conversation, 18 June 2019, <https://theconversation.com/secrecy-over-paladins-423-million-contract-highlights-our-broken-refugee-system-118996>; and Sharon Labi, ‘Aussie Taxpayers Funding Multi-billion-dollar Detention Centre Bill’, 9News, 27 July 2020, <https://www.9news.com.au/national/australia-detention-taxpayer-costs-serco-parliamentary-inquiry-figures-politics-news/c90d7552-0a83-4ad4-84c6-4ce6fd1366be>, both accessed 1 October 2021. |

| 44 | See Ben Doherty, ‘Three Members of Biloela Family Granted Year-long Visas but They’ll Have to Remain in Perth’, The Guardian, 23 September 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/sep/23/three-members-of-biloela-family-granted-year-long-visas-but-theyll-have-to-remain-in-perth>, accessed 1 October 2021. |