Little more than a series of loosely connected sexploitation vignettes surrounding the sexual exploits of its eponymous protagonist, Tim Burstall’s Alvin Purple (1973) was the most successful film at the Australian box office from the years 1971 to 1977.[1]Errol Vieth & Albert Moran, Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, 2005, p. 49. Following Alvin (Graeme Blundell) from schoolboy to waterbed salesman to gigolo, the film was the first big Australian blockbuster of the 1970s:[2]Scott Murray, ‘Australian Cinema in the 1970s and 1980s’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Cinema, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 73. it opened in Sydney and Melbourne at Hoyts in December 1973,[3]Catharine Lumby, Alvin Purple, Currency Press, Sydney, 2008, p. 22. and took more than A$4 million net.[4]ibid., p. 24. By late the following year, it had gone on to become the ‘most profitable Australian feature to date’ at the time.[5]Graham Shirley & Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, Currency Press, Sydney, 1989, p. 268.

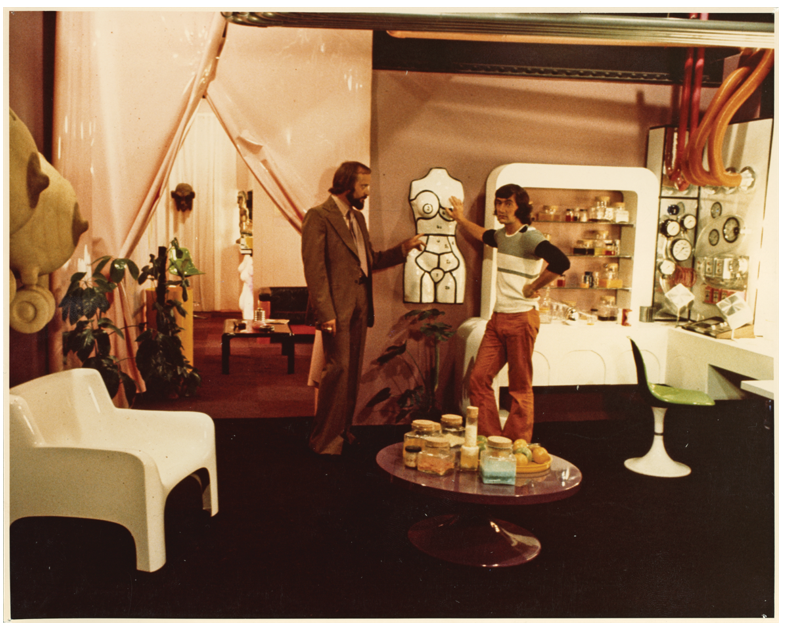

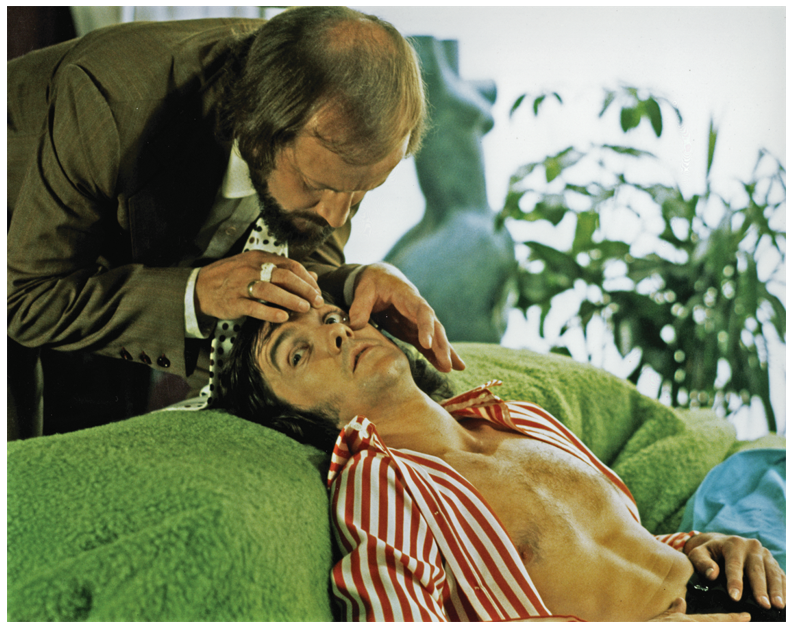

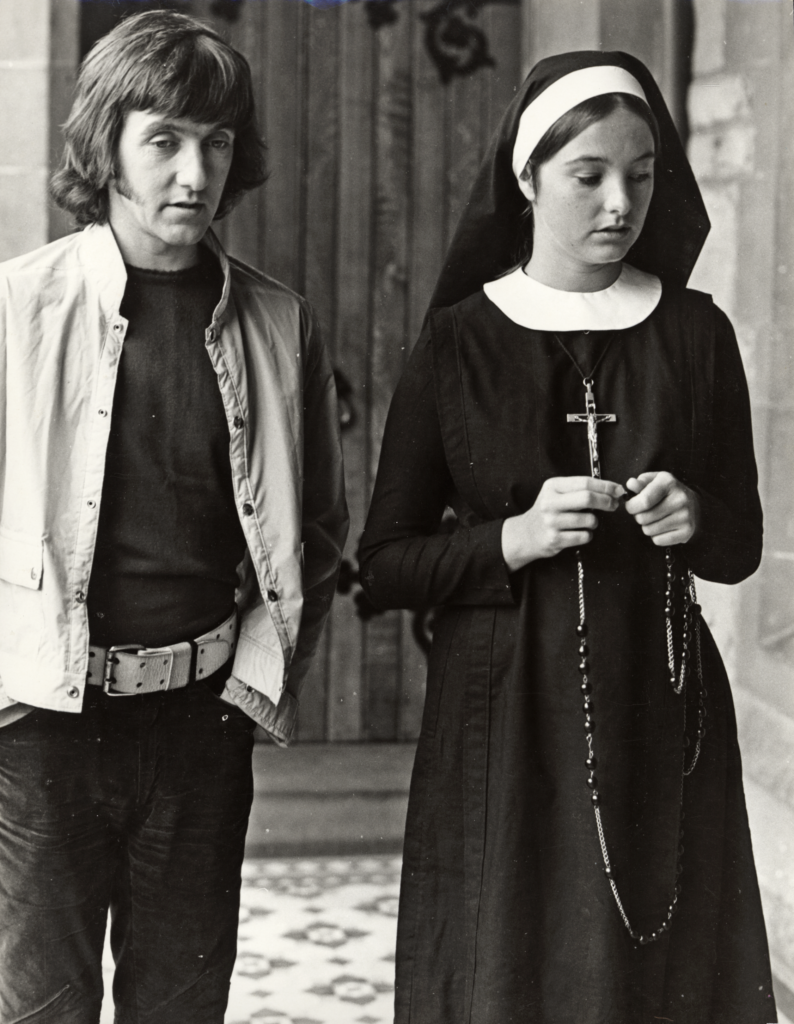

The film begins as the high-school-aged Alvin is assisted by sympathetic male schoolteacher Mr Horwood (Dennis Miller), who offers the boy with magnetic sexual allure an early mark so as to avoid the aggressive pursuits of his female classmates. It is perhaps ironic, then, that Alvin’s first sexual encounter is with the teacher’s wife, Mrs Horwood (Jill Forster). Turning to retail after his twenty-first birthday, Alvin’s brief stint selling waterbeds puts him in close proximity to a range of new sexual partners, again seemingly incapable of resisting his sexual charms. The film documents Alvin’s sexual adventures in loving detail, including liaisons with characters played by iconic 1970s Australian sex symbols Jacki Weaver and Abigail. Turning to psychiatry for help in an attempt to overcome his inability to resist the sexual attentions of women en masse, Alvin soon finds himself in the employ of Dr McBurney (George Whaley) as – effectively – a sex worker who receives women clients the specialist ‘refers’ to him for a kind of medically beneficial sexual ‘treatment’. Dr McBurney’s colleague Dr Liz Sort (Penne Hackforth-Jones) – jealous and hurt by Alvin’s earlier rejection of her sincere affections for him – reveals their business arrangements to the law, which not only lands Alvin in court but also makes him a social pariah. With the support of his girlfriend, Tina Donovan (Elli Maclure), the only woman who appears to have any resistance to his magnetism, Alvin finally emerges victorious, and the film concludes with her in a convent as Alvin works happily in the gardens among her and her chaste peers.

A key work in the Australian film renaissance of the 1970s, Alvin Purple has critically been both condemned and championed. But, despite these positions, the film is almost always framed very much as a product of its time. This reconsideration seeks to explore what the film might offer audiences today, over forty years since its initial release. While undoubtedly problematic in many key instances – its flagrant transphobia and the jokey acceptance of its protagonist’s sexual-assault fantasies numbering among them – it is Alvin’s very ‘softness’ and its relationship to these aspects of the narrative that offer a direct legacy on the kind of discourse that now surrounds gendered violence in contemporary Australia. Less negatively, in some of its most memorable sex vignettes, Alvin Purple offers a vibrant spectacle of the beauty and joy of gendered bodies in full sexual flight, the likes of which are – even by today’s standards – rarely seen on screen in Australia or elsewhere.

Alvin then

Noting distributor/exhibitor Village Roadshow’s ability ‘to think outside the square’, Ben Goldsmith, Susan Ward and Tom O’Regan identify that the company’s preliminary involvement in production came with the formation of Hexagon Productions with Alvin Purple director Tim Burstall and the production house Bilcock & Copping. As their first film project, Alvin Purple proved a remarkably successful investment for Village Roadshow, rendering it ‘the first major Australian exhibitor to directly assist the revival of Australian feature film production’.[6]Ben Goldsmith, Susan Ward & Tom O’Regan, Local Hollywood: Global Film Production and the Gold Coast, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2010, p. 123. Numerous critics have emphasised the contrast between Alvin Purple’s financial success and its critical dismissal,[7]See, for example, ibid.; Murray, op. cit., p. 73; and Shirley & Adams, op. cit., p. 268. the latter typified by John Tittensor’s 1974 Cinema Papers review, which mused:

How is a sex comedy to be wrung from people whose idea of what’s funny is at best rudimentary and whose appreciation of the significance, as distinct from the practice, of sex is either non-existent or so vulnerable to commercial pressures as to be beneath consideration?[8]John Tittensor, quoted in Lumby, op. cit., pp. 23–4.

Yet, as Catharine Lumby cannily indicates, not all initial reviews were so dismissive: Sandra Hall at The Bulletin, for example, called the film ‘cheerfully sexist, unashamedly mindless and, in the carry-on manner, leaves no innuendo unexploited’.[9]Sandra Hall, quoted in Lumby, ibid., p. 23. In terms of its commercial appeal, however, there was little debate: the film inspired the sequels Alvin Rides Again (David Bilcock & Robin Copping, 1974) and Melvin: Son of Alvin (John Eastway, 1984) as well as a thirteen-part 1976 ABC television series. Goldsmith, Ward and O’Regan also emphasise its appeal on the drive-in circuit, and to its primarily young-adult demographic.[10]Goldsmith, Ward & O’Regan, op. cit., p. 123.

Along with Stork (Tim Burstall, 1971) and The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (Bruce Beresford, 1972), Alvin Purple is often said to typify the so-called ocker films that, according to Errol Vieth and Albert Moran, ‘celebrated the more vulgar side to an alleged typical “Australiannness”’.[11]Vieth & Moran, op. cit., p. 53. For O’Regan, ‘a defining characteristic of ocker was its unabashed celebration of the “Australian”, particularly the vernacular, whether in speech, content, or action’. He continues:

This celebration was couched in aggressively Australian or ‘strine’ accent. If ocker represented the elevation of slang and bad manners it did so in the context of an inventive, usually male, anti-language for bodily functions, sex, drinking and women. Ocker implied a resolutely hedonistic outlook. Out of this sprang its obsessive concern with the pleasures of the body. This led not only to the highlighting of drinking alcohol but also to the highlighting of sex – getting enough of it, not getting enough of it – talking about it – such that emotional relationships, marriage, even mateship were seen to hinge upon it.[12]Tom O’Regan, ‘Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1989, p. 76.

For Vieth and Moran, the ocker movies ‘had financial success at home and were popular overseas, and thus pointed the way to the possibility of a revived Australian film industry’.[13]Vieth & Moran, op. cit., p. 53. These films, in large part, capitalised on cultural shifts in Australia towards a more liberal approach to film censorship in the late 1960s, which were rendered formally through a relaxation of federal policies under the governance of then–customs minister Don Chipp; this, in turn, led to the creation of the R certificate in 1971.[14]ibid., p. 83. A number of changes to Australian film culture were subsequently effected: films were censored and banned less, mainstream cinemas benefited from a rise in box-office takings, tiny newsreel theatres were converted into ‘R houses’, while drive-ins began introducing separate screenings for G-rated family films and more adult, M-rated later sessions for older audiences. It was in this climate that sexploitation films like Stork and Alvin Purple sought to profit from these broader cultural shifts for their own benefit, upping the sex and nudity as promotional drawcards.[15]ibid. For Scott Murray, this climate precisely explains why sex comedies such as Alvin Purple ‘represented the first wave of the Australian renaissance’, as ‘[l]ocal film-makers sought to cash in on this market’.[16]Murray, op. cit., p. 73.

Despite its popular appeal, however, Alvin Purple’s origins lie in a far more elite cultural sphere. Burstall himself had won an award at the Venice Film Festival in 1960 for his short film The Prize, but, despite this achievement, the dismal state of the local industry was such that it took nine years for him to attempt a feature film. The time in between was spent directing for television, making short films (predominantly documentary in tone, and almost all on Australian art and artists). As Lumby notes, when the feature 2000 Weeks was made in 1969, ‘the Australian film industry was in a state of abject crisis – less than fifty domestic feature films had been made between the years 1940 and 1964’.[17]Lumby, op. cit., p. 15. But 2000 Weeks was a commercial and critical disaster, and it was not until Stork that Burstall’s fortunes began to shift. Although Stork was one of the first ocker comedies and hits of the Australian New Wave, its origins revealed Burstall and his collaborators’ far-from-ocker social milieu – the film was, for starters, based on David Williamson’s play The Coming of Stork, which had played at Carlton’s legendary experimental playhouse La Mama Theatre,[18]ibid., p. 18. an iconic institution in Australian avant-garde performance history opened by Burstall’s late wife Betty in 1967. Burstall himself was educated at prestigious institutions such as Geelong Grammar School and the University of Melbourne,[19]ibid., p. 20. supporting Lumby’s broader point that ‘as was also true of the Barry McKenzie movies, many of those involved in making Alvin were actually drawn from the contemporary intellectual and cultural elites’.[20]ibid., p. 18. As Michelle Arrow notes, these kinds of ‘crossovers between the new [Australian] cinema and radical theatre’ was not unique to Burstall, observing that Blundell himself was part of the ‘countercultural’ Australian Performing Group (APG).[21]Michelle Arrow, Friday on Our Minds: Popular Culture in Australia Since 1945, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009, p. 114.

The gender politics presented in Alvin Purple are, by contemporary standards, archaic, strange and at times … undeniably shocking. Yet, at other times, the film celebrates a love of sex that, in a post-HIV world, is rarely depicted with such boisterous simplicity.

These origins clarify the logic driving one of Alvin Purple’s primary sources beyond the ocker model so successfully brought to the screen in previous years with both Stork and Barry McKenzie. For Moran and Vieth, the British sex comedy Tom Jones (Tony Richardson, 1963) – based on Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling – was a clear influence on Alvin Purple, noting that it ‘owes much of its overall structure, most especially in its second half, to the “mock epic” structure of both the British film and the Fielding novel on which it was based’.[22]Albert Moran & Errol Vieth, Film in Australia: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2006, p. 62. Yet, for O’Regan, Alvin Purple also ‘extended the project begun with The Naked Bunyip [John B Murray, 1970] and to a lesser extent Libido [Fred Schepisi et al., 1973]’[23]O’Regan, op. cit., p. 85. – films far more explicitly sexual than either Barry McKenzie or Stork.

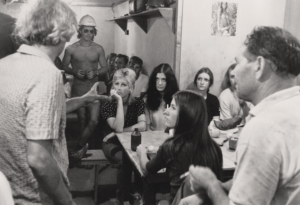

This intersection of cinematic titillation and classic literature manifested in Alvin Purple in other ways. On the back of Stork’s success, the Alvin Purple project began when Burstall sought ideas for sexploitation vignettes from a number of writers, seeking to cash in on the rise of both sexploitation itself and sexually explicit content in more highbrow art cinema at the time.[24]Lumby, op. cit., p. 21. Hexagon had initially intended to launch with the drama Petersen (eventually directed by Burstall in 1974, the film starring Weaver, Jack Thompson and Wendy Hughes), but it was postponed. In the interim, Burstall conceived a portmanteau film consciously modelled on Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1971 film The Decameron – itself based on a novel by fourteenth-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio – which had been hugely successful in Australia following the loosening of censorship restraints. Although story ideas came in from authors of high calibre, including Williamson, Bob Ellis and Frank Hardy, it was one by Alan Hopgood that provided the bare bones of Alvin Purple; Burstall was so impressed with it that he discarded the portmanteau idea and decided to expand the Alvin Purple segment to an entire film.[25]Shirley & Adams, op. cit., p. 268. With a mostly improvised script, the film began shooting in March 1973 for five-and-a-half weeks with a budget of A$202,000, A$500 of which per week was paid to Blundell as lead actor.[26]Lumby, op. cit., p. 22. This budget allowed the film to be shot on 35mm – an upgrade from Stork, which was shot on 16mm and then ‘blown up to 35mm’.[27]ibid.

Alvin now

Put simply, Alvin Purple was a phenomenal commercial success. But the critical backlash to the film – and defences of it – far outlasted its commercial longevity.

Despite the film being widely considered a key part of the ocker tradition that played such an important role in the Australian film renaissance of the 1970s, many critics have noted that Alvin himself is distinctly not ocker. But, in light of the ‘ocker’ category’s almost-aggressive concern with bodies and the bodily, the sexuality displayed in Alvin Purple perhaps understandably makes it enough to forgive the film’s being classified as one, despite Alvin’s own obvious lack of ‘ockerishness’. On this front, the original context of Alvin Purple is crucial. As Lumby notes, Burstall’s film ‘arrives on the brink of enormous social change but before the broader Australian public had processed their own personal positions on issues around sexual liberation and feminism’. She also asserts that

Alvin is a film set at a time before the term ‘sexist’ was routinely applied to sexualized representations of women. It was made when the so-called sexual revolution (or at least the titillating idea of it) was beginning to go mainstream in Australia and on the cusp of a broader awareness of the growing feminist backlash against the inequality that has so often underpinned the promise of sexual freedom. It was a period in which Australian women were beginning to openly explore their sexual subjectivity, their desires and their relationships to their traditional roles as sexual partners, wives and mothers.[28]ibid., pp. 31, 30.

At the same time, however, it would be unhelpful to lean too far towards essentialist readings of women’s sexuality at the time and how it pertains to the reception of Alvin Purple. While Lumby claims that the movie ‘reflects and refracts so many of the cultural, political and sexual anxieties of its time’, especially in regard to ‘the nudge-nudge humour, the anxiety about where female sexual desire fits into heterosexuality, the electricity of burgeoning cultural and political change’,[29]ibid., pp. 3–4. Susan Magarey notes – with reference to the case study of a woman named Joyce Nicholson – that this was not the case for all women:

Joyce Nicholson was having her first experience of a demonstration in Bourke Street in Melbourne at the time when the film was screening. Young women from Women’s Liberation were directing the march. They would shout through their loudspeakers ‘What do you want?’ and the marchers would reply ‘We want equality!’ ‘When do you want it?’ ‘Now!’ And as they reached the movie-theatre, the young women shouted, ‘Fuck Alvin Purple!’ ‘I remember’, said Joyce, ‘we all shouted “Fuck Alvin Purple!” Well, I’d never used the word “fuck” in my life’.[30]Susan Magarey, Dangerous Ideas: Women’s Liberation – Women’s Studies – Around the World, The University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide, 2014, pp. 23–4.

Magarey pinpoints that, in Nicholson’s case at least, Alvin’s ‘nudge-nudge humour and anxiety about female desire’ were simply not part of the world that she had experienced. She adds that her leaving that world was very distinctly through the women’s movement itself protesting against Alvin Purple: ‘Joyce had been brought up very strictly […] For her, sexual liberation came with and from Women’s Liberation, not from either the Pill or the sexual revolution.’[31]ibid., p. 24. To champion Alvin Purple in a purely historical sense as a kind of blanket symbol for a mass awakening of the national sex-political consciousness risks losing the value of stories like Nicholson’s, even if they are the exception and not the rule.

Likewise, few acknowledge that the gender politics presented in Alvin Purple are, by contemporary standards, archaic, strange and at times – particularly with regard to the aggressive, unabashed transphobia – undeniably shocking. Yet, at other times, the film celebrates a love of sex that, in a post-HIV world, is rarely depicted with such boisterous simplicity. As will be elaborated on shortly, the body-painting sex scene in particular is surely one of the most joyful representations of human copulation in Australian cinema history. The challenge with Alvin Purple, then, is to keep a historical perspective so as to avoid dehistoricising the film completely while simultaneously finding a space to talk about the experience of watching the film today, over forty years since its initial release.

If Lumby and O’Regan are anything to go by, this sense of forgiveness appears to be easier for older critics who remember the film at its time of release than younger ones who discovered it for the first time on DVD in more recent years. As a member of the latter category, my difficulties with Alvin Purple begin before the opening credits even appear: the film commences with the eponymous hero of the film fantasising about sexually assaulting a woman on a tram, leading to the actual sexual harassment of another. As a voiceover laments the loss of the protagonist’s youthful success with women and begrudgingly welcoming the ‘sexless seventies’, Alvin daydreams about walking up to a young woman on the tram, ripping her blouse open and exposing her breasts. Soon after, he imagines an idealised scenario in which he successfully propositions another woman by complimenting her on her ‘breasts’, the mechanics of the gag reliant on a quick cut to the reality of the situation whereby he bluntly tells the same woman she has nice ‘tits’. As Lumby describes it, the traditional assessment of this scene at least implies that ‘the young women are dressed provocatively and fashionably in stark contrast to the prim clothing and gazes of the matrons on the tram. Alvin can’t help having sex on his mind.’[32]Lumby, op. cit., p. 26. Notions such as this echo notions I myself find deeply troubling, especially in the context of contemporary Australia: Boys will be boys. The girls were asking for it.

Watching and reading about Alvin Purple today, there is a sense that critics of a certain generation have been eager to draw a generational line in the sand: you weren’t there, you don’t get it. As O’Regan noted in 1989, Alvin Purple was ‘a film for a particular time in the cinema’. As a softcore sex comedy, ‘Alvin represents the precarious position of socially acceptable “porn” before the opening up of R circuits showing films devoid of the panache and humour of Alvin’; as such, Burstall’s film and those like it ‘are not so much films in a film world as films with a particular kind of relation to their social audience of the time’.[33]O’Regan, op. cit., pp. 85–6. Framing her lengthy assessment of the film in proudly subjective terms – she talks warmly of writing ‘Alvin’ on her pencil case in purple texta as a thirteen-year-old, love heart over the ‘i’ and all[34]Lumby, op. cit., p. 3. – Lumby, too, suggests much of the film is destined to remain untranslatable for contemporary audiences:

Modern viewers of Alvin Purple are likely to find the appeal of the double entendres and Brian Cadd’s speeded-up Benny Hill-style music (which signals to viewers that ‘girls are chasing men’) baffling. If you grew up though, as I did, with British nudge-nudge jokes there’s an element of nostalgic camp in this kind of comedy.[35]ibid., p. 25.

Lumby defends these aspects by claiming that ‘Alvin shouldn’t have to live or die in Australian film history on the grounds of how well it translates for contemporary viewers’. Instead, she argues strongly that the film’s real legacy is its representation of masculinity in crisis, and how certain kinds of films celebrating sex were – for this brief moment in Australian film history – mainstream box-office catnip.[36]ibid.

Both watching the film today and reading the criticism around it, claims such as this contain an air of warning – an implied suggestion that to do so would find a younger critic in the midst of some kind of weird Baby Boomer territorial land-claim. As Lumby’s Benny Hill reference indicates, Alvin Purple should, of course, not be simplistically dismissed for its overt markers in both formal style and – more significantly – ideological position in terms of representation. But, surely, this does not mean Alvin Purple should be protected by some kind of invisible wall of nostalgia against contemporary assessments. Like Lumby, I agree that its significance today lies in what it can tell us about Australian masculinity – but, for me, Alvin’s softness and status as the ‘everyman’ are far more foreboding. And this does not refer to only the character himself: watching Alvin Purple in 2016, the tits-and-arse humour, I can understand when placed in the context of its era of production. What sits less easily, however, is – for starters – the fact that the film opens with a fantasy of sexual assault by its supposedly lovable ‘everyman’ protagonist.

Much has been made by critics of Alvin’s status as an everyman. As Murray contends, ‘[t]he aim was for audiences to identify with an “ordinary” guy who “got lucky”’.[37]Murray, op. cit., p. 73. For O’Regan, not only is Alvin ‘both a gentleman and a “normal” man with normal appetites’, but it is almost he who is the victim:

Alvin is about a man pursued from adolescence by girls and women who mostly seek to offer themselves to him while at other times seeking mindlessly to ravish him. Alvin’s mundane goals of leading a quiet, normal life and having a normal emotional and sexual relationship with his girlfriend are continually frustrated by both the circumstances of his attractiveness to the opposite sex and the assumed impossibility of his ability to refuse their sexual advances.[38]O’Regan, op. cit., p. 86.

Alvin is far from the Australian ocker ‘hard man’, with the titular character of Barry McKenzie (Barry Crocker) at one end of the spectrum, Mick (Paul Hogan) of Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986) somewhere in the middle, and Mick Taylor (John Jarratt) of Wolf Creek (Greg McLean, 2005) at the other end. Mick Taylor offers a useful counterpoint from which to consider an unlikely avenue of critical investigation that O’Regan alludes to but does not explore further. When taken in the context of Alvin’s ‘fantasy’ sexual assault in the film’s opening scene, however, this wave to horror may assist in casting Burstall’s film in a new light. Discussing the myriad aggressive sexual attention that Alvin receives from the bulk of the film’s female characters, O’Regan notes: ‘If Alvin were to resist these advances his normality and libido would be in question. Thus the film is able to position Alvin as simultaneously ultra-normal and monstrous.’[39]ibid.

This monstrosity works two ways, however, casting the aggressive sexual pursuit of Alvin as ‘no less than an elaborated vagina dentata structure’.[40]ibid. At the time O’Regan was writing on Alvin Purple, Barbara Creed’s book The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis was still a few years off, but his evocation of violent feminine monstrosity is difficult to avoid: the implication, it seems, is that there is a kind of violence implicit in the assertive female sexuality on display in Alvin, which – when juxtaposed with the literal act of sexual violence Alvin fantasises about – suggests that, while not exactly ‘rape-revenge’ in the most traditional sense, the film affords these women a degree of table-turning upon Alvin and so-called ‘soft’ predators like him.

Alvin Purple is – as its opening moments make clear – not just a comic sex fantasy, but it is explicitly, on Alvin’s part, told through the character’s own fantasies of sexual violence. The very women who seek to seduce Alvin (whom he finds somehow impossible to resist, thus denying his own ability to control himself – boys, it seems, again, will be boys) are framed, therefore, as sharing the tendency towards sexual aggression: ‘soft’ men might daydream about sexually assaulting women on trams, the film suggests, but look, women can’t keep their hands off poor Alvin! This is despite the fact that ‘poor Alvin’ is an active participant in almost all of his sexual encounters except – importantly – those with Dr Sort, which are the products of her blackmailing him. Yet, even here, it is worth pointing out that she herself suffered workplace sexual harassment at the hands of her boss, Dr McBurney. There’s an echo again of the rape-revenge tradition, particularly contemporary manifestations whereby women who have survived sexual assault in turn use it as a weapon for their vengeance.[41]See, for example, Straightheads (Dan Reed, 2007), The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Niels Arden Oplev, 2009; David Fincher, 2011), and Steven R Monroe’s 2010 remake of Meir Zarchi’s 1978 exploitation classic I Spit on Your Grave. As awful as her behaviour is, it pales next to those opening few moments of the film in which our ‘hero’ is introduced as a man who daydreams about assaulting women. While, to Lumby, it was ‘the passivity of the Alvin character [that] was a revelation to [her] when [she] first revisited the film’[42]Lumby, op. cit., p. 27. in 2008, for me it was the privileging of Alvin’s sexual assault fantasies in this introductory scene that came as the real shock. Watching the film again in 2016, I find the film undeniably fascinating; however, because of this opening, Alvin always remains at a remove from my experience of the film: he’s not lovable, but is instead rather typical of the kind of masculine thuggery that Australia has a long tradition of simultaneously privileging and excusing, from Ned Kelly to Chopper Read.

Alvin Purple is not exactly The Birth of a Nation (DW Griffith, 1915), but Lumby is correct in asserting that Alvin’s worth as a piece of Australian cinema shouldn’t be evaluated solely by contemporary standards.[43]ibid., p. 25. But surely Alvin himself shouldn’t get away criticism-free. And, I would argue, there is a contemporary relevance – even urgency – to that opening scene, and how it stands in the broader context of the film itself and its critical history: with its ‘soft everyman’ protagonist, the sympathetic sexual assailant we are introduced to offers unique insight into historical traces of a cultural phenomenon that are only too relevant in contemporary Australia, particularly in terms of sexual violence. When Lumby notes that ‘there’s been remarkably little written about the way a film like Alvin Purple points up male anxieties about gender and sexuality’,[44]ibid., p. 28. she is referring to the film in a historical context, pertaining to its era of production and initial release. But in its depiction of a ‘soft everyman’ who daydreams of sexually assaulting women – and the championing of this kind of masculinity as somehow representative of ‘true’ Australian masculinity – it becomes impossible, in 2016, to avoid the outcome of that logic. We hear its echoes in public discourse every time the agency and subjectivity of women in cases of assault is denied. We hear it in Mark Latham’s vitriolic attacks on domestic violence campaigner Rosie Batty,[45]John Carney, ‘“A Generalised Campaign Against All Australian Men”: Mark Latham Attacks Australian of the Year Rosie Batty on Triple M for Her Work Opposing Domestic Violence’, Daily Mail, 22 January 2016, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3411207/Mark-Latham-attacks-Rosie-Batty-s-domestic-violence-campaign-Triple-M-radio-show.html>, accessed 11 November 2016. and in his claims that men are the real victims who turn to domestic violence as a ‘coping mechanism’.[46]‘Mark Latham: Former Labor Leader Says Domestic Violence a “Coping Mechanism” for Men’, ABC News, 22 January 2016, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-01-22/mark-latham-under-fire-for-triple-m-podcast-domestic-violence/7107650>, accessed 11 November 2016. We hear it when it is suggested that women who go home with AFL players are somehow asking for it, and surely aren’t expecting just ‘a cup of Milo’.[47]In 2010, in light of a scandal surrounding a woman’s allegations of sexual assault against a Collingwood Football Club player, Peter ‘Spida’ Everitt notoriously tweeted: ‘At 3am when you are blind drunk & you decide to go home with a guy ITS NOT FOR A CUP OF MILO!’; see Thomas Hunter & Will Brodie, ‘“Spida” Turns on Women over Collingwood Sex Allegations’, The Age, 5 October 2010, <http://www.theage.com.au/afl/afl-news/spida-turns-on-women-over-collingwood-sex-allegations-20101005-1659d.html>, accessed 11 November 2016. This is our current crisis of masculinity. And the positioning of the sexual assault fantasy at the beginning of Alvin Purple and the ‘free pass’ it has received both in the film itself and from critics reveal an awkward truth: we have championed as iconic and loveable this so-called hero we see as a comic victim of his own attractiveness, regardless of the fact that he daydreams about sexually assaulting women. Alvin Purple is, from this perspective, inescapably a troubling watch in 2016, which raises an important question: in the face of all this, is there anything left to redeem it?

Alvin forever

The real legacy of Alvin Purple, as Lumby sees it, is what it ‘tell[s] us about what it was possible to do in Australian film-making then and now’.[48]Lumby, op. cit., p. 53. Reciting the oft-told narrative of Australian cinema history, she recalls that, after an onslaught of critical and institutional attacks, ‘the anti-ocker forces won out and Australian cinema took a very different turn […] becoming hailed as a standard-bearer for a much-touted Australian cultural renaissance dominated by arty period films’.[49]ibid., p. 65. The success of Alvin Purple leads Lumby to a question that dominates Australian film-criticism discourse today:

what future is left for Australian films that deal in themes that attract large local audiences but don’t cross over into the international market[?] Where, in other words, are the local films that speak to and entertain mainstream Australian audiences? Why do so many Australian films fail at the local box office? Is the local audience now so irreversibly split into those who are only interested in seeing high-budget Hollywood movies and those who dutifully trot off to see ‘serious’ local fare?[50]ibid.

If its critical history is anything to go by, Alvin Purple seems to be predominantly quarantined to the somewhat-limited space of ‘historically significant’, which, while a successful method of eliding the undeniably icky aspects of its gender politics, also risks turfing the metaphorical baby with the bath water. When I watch the film today – although with a distance from the character of Alvin for the reasons outlined above – I am struck by the fact that Alvin Purple is simply, at times, a gorgeous film. A cursory stroll through some of its more memorable sequences underscores that, although Alvin Purple might have lost something crucial over time in terms of its ideological acceptability, it does not lack a distinctly and proudly Melburnian gloss and a fundamental love of spectacle, be it centered on flesh, face or space.

Alvin Purple is, aside from anything else, a love letter to Melbourne. The sexual assault fantasy is introduced with a close-up of a now soon-to-be-phased-out W-class tram as it barrels along what was then Route 64: although the route may have changed, this same route today services the journey between the University of Melbourne and East Brighton, just down from St Kilda on Port Phillip Bay. But it is in the film’s climax – itself a word appropriately full of smutty innuendo – that Alvin Purple reaches peak Melbourne status. After being acquitted in court of criminal wrongdoing, Alvin’s brief sojourn at home is interrupted by an angry mob of men: the husbands of the women Alvin had ‘serviced’ during his time working for Dr McBurney. Chased to a skydiving centre, Alvin hides on a plane and is forced to jump from it over the Yarra River, running along the foreground in front of Melbourne’s 1970s cityscape. Drenched and befouled by its iconic sludge, Alvin climbs out of the river and heads to Alexandra Gardens, only to again find himself prey to a group of sexually aroused young women, seemingly unable to resist his sexual magnetism. The chase that follows is a joy to watch, showing an old Melbourne starkly different from the sanitised, tourist-friendly version of official memory: this is the everyday Melbourne of the early 1970s. We are taken past St Paul’s Cathedral across from Flinders Street Station, along busy Swanston Street, and arrive at the corner of Collins and Elizabeth streets, where Alvin is ‘rescued’ by a sympathetic policeman before finding true peace with girlfriend Tina at a local monastery.

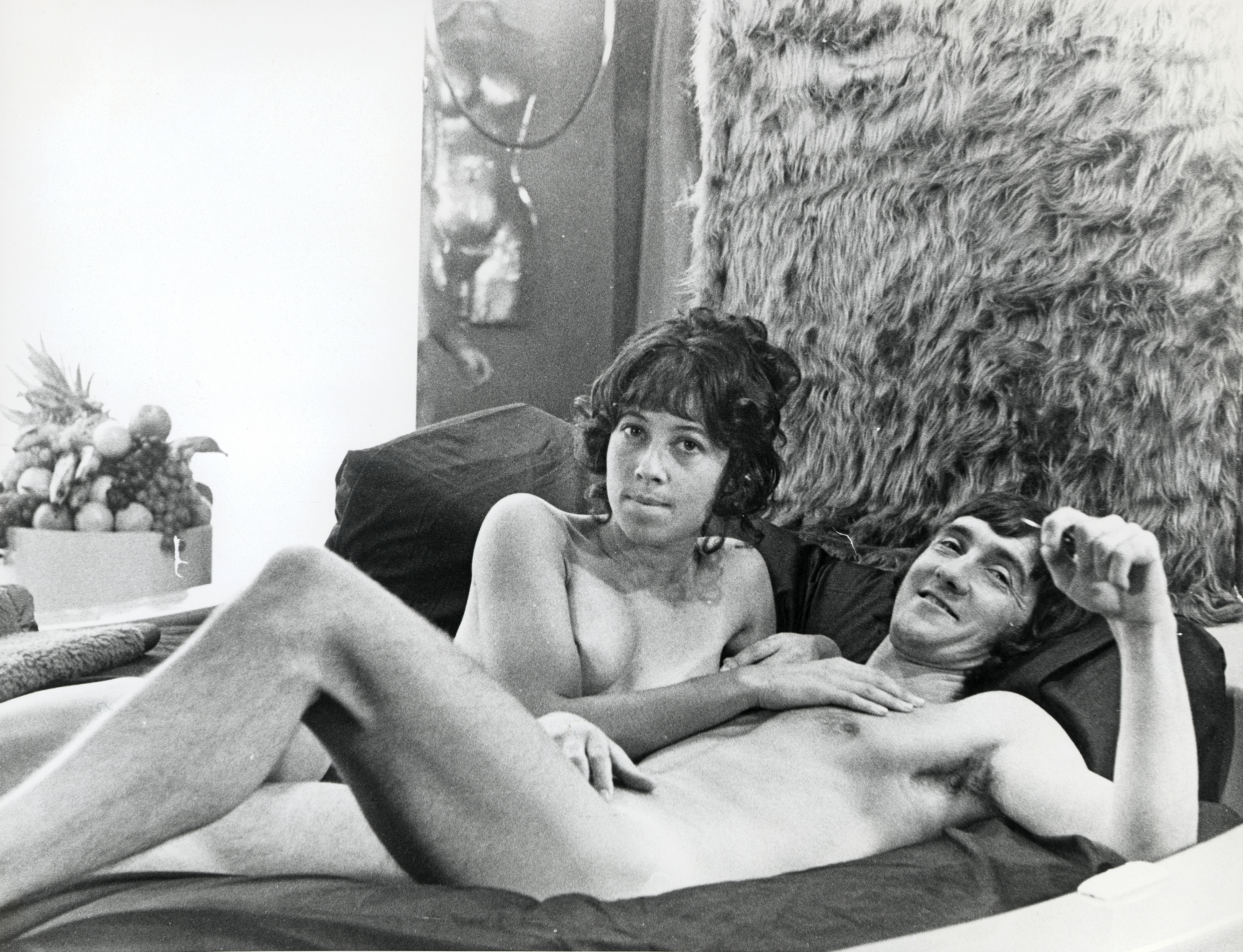

But Alvin Purple’s most memorable offerings are its few uncomplicated, joyful depictions of hetero-sex. After his twenty-first birthday, Alvin looks for a job to suit his ‘special talents’ and ends up hired to sell waterbeds in the homes of potential customers. This is the section of the film in which Alvin’s prowess with women is first displayed in quick succession – and, despite the uncomfortable transphobic ‘gag’ that is unquestionably difficult to excuse from a contemporary perspective, the range of women he attracts is broad in terms of ages and class. It is here that the sex scene involving body paints finds itself; it is probably the most playful moment of the entire film, and certainly the site of its greatest and most enduring visual spectacle. This is, in no uncertain terms, a beautiful sequence, as both Alvin and his partner revel in the muck of entwined bodies, the bright, synthetically coloured paints swirling and merging to an earthy, primal brown as their coitus reaches its conclusion. Little is said during the body-painting sex scene because little needs to be: faces smile, bodies writhe, colours rise and fall. For a brief instance, gendered bodies – and all the complicated ideological baggage that comes with them – collapse into shape, tone and movement. This scene is and always will be Alvin Purple’s crowning achievement.

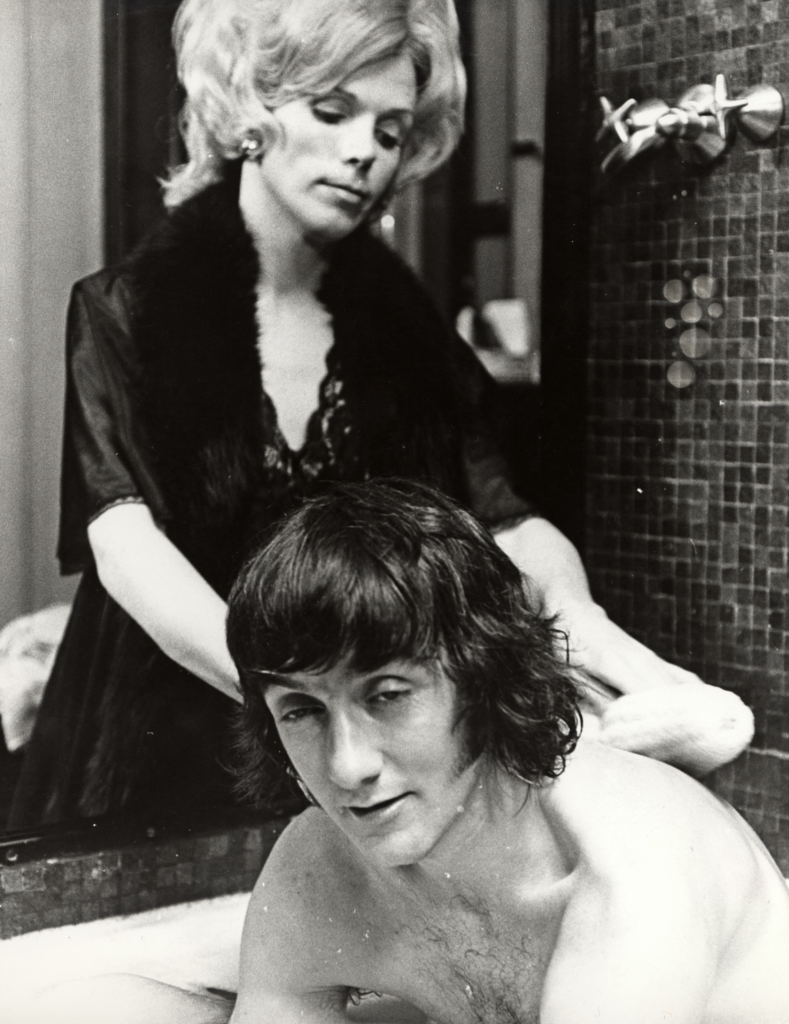

Although not as visually compelling in its simplicity and form, a subsequent S&M encounter is another sex vignette we see early on in Alvin’s waterbed-salesman period that briefly transcends the specificity of its era of production. Certainly, the strong ‘dominant’ woman with the whip and spurs speaks to the emerging popular image of ‘liberated’ women so culturally potent at the time, but there’s much more going on here. Reflecting the broader anxieties about masculinity in this context that Lumby has examined in depth, Alvin seems unsure of how to negotiate this sexual encounter until the spurs pierce the waterbed, flooding the setting with water and pitting its participants as soggy, giggling equals. Again, there is something elemental to this particular moment: instead of colour, here the dominant element is water, reducing its participants to something wholly primal, almost pre-ideological, with notions of ‘equality’ seemingly natural givens rather than sociopolitical sites for struggle. Taken in the context of the film as a whole, this and the body-painting sex vignette in particular stand out for this very reason. Regardless of their gender, the participants in these two sequences look more comfortable and at home in these stylised moments than in any of the more supposedly ‘realistic’ (in terms of setting and dialogue) sex scenes elsewhere in the film.

And it is precisely due to moments such as these that we should celebrate the film. Of all the aspects of Alvin Purple that Lumby champions, that people look like they are having fun when they have sex is the most simple and yet the most significant: ‘it seems so hard to imagine what positive images of women and men having sex might look like in mainstream Australian movies’.[51]ibid., p. 69. The point is a good one: there are no other instances in Australian film that I can think of that come close to Alvin Purple’s body-painting scene and its sheer celebration of shagging, depicted as a joyful experience for both participants. But it may be worthy of note that the kind of rampant sexuality depicted in Alvin Purple predated the rise of HIV – the kind of sex romp that Alvin’s story revels in is very much an artefact from another time entirely. In the specific context of Australia, maybe it’s simply a lot harder at this present point in time to joke about sex in a culture where cases of gendered and domestic violence are on the rise, when there are government-sanctioned camps on Nauru where refugees are raped, and when good old AFL boys are slapped on the wrist for sexual assault.

It goes without saying, then, that the kinds of sexual anxieties to which Alvin Purple speaks are therefore not the same as the sexual anxieties that concern us now. And perhaps even more generally, from a contemporary perspective, it’s hard to watch Alvin Purple today and accept that the story of a sex addict is an appropriate subject for comedy: now that this compulsion is considered less a key to ‘sexy good times’ than a significant clinical disorder, the types of films we get about the subject are less Alvin Purple than they are far more tonally bleak fare, such as Steve McQueen’s Shame (2011) and Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac (2013). So, while accepting Alvin Purple today as a radical or instructive text beyond its original context in any sense is a difficult pill to swallow, what remains less debatable is this: the film is, in its best moments, unapologetically joyous in how it celebrates the spectacle of returning to the elemental, transcending politics and making sex our own.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Paul Harris, Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild Untold Story of OZploitation!, Madman Entertainment, Melbourne, 2008.

John Hinde, ‘Barry McKenzie and Alvin Ten Years Later’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985.

Catharine Lumby, Alvin Purple, Currency Press, Sydney, 2008.

Scott Murray, ‘Australian Cinema in the 1970s and 1980s’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Cinema, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994.

Tom O’Regan, ‘Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1989.

Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film, 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980.

Graham Shirley & Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, Currency Press, Sydney, 1989.

MAIN CAST

Alvin Purple Graeme Blundell Dr Liz Sort Penne Hackforth-Jones Dr McBurney George Whaley Tina Donovan Elli Maclure Spike Dooley Alan Finney Mr Horwood Dennis Miller Mrs Horwood Jill Forster Judge Noel Ferrier

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1973 Length 97 minutes Director Tim Burstall Producer Tim Burstall Original Screenplay Alan Hopgood Cinematographer Robin Copping Editor Edward McQueen-Mason Production Manager Hal McElroy Art Director Neil Angwin

Endnotes

| 1 | Errol Vieth & Albert Moran, Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, 2005, p. 49. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Scott Murray, ‘Australian Cinema in the 1970s and 1980s’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Cinema, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 73. |

| 3 | Catharine Lumby, Alvin Purple, Currency Press, Sydney, 2008, p. 22. |

| 4 | ibid., p. 24. |

| 5 | Graham Shirley & Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, Currency Press, Sydney, 1989, p. 268. |

| 6 | Ben Goldsmith, Susan Ward & Tom O’Regan, Local Hollywood: Global Film Production and the Gold Coast, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2010, p. 123. |

| 7 | See, for example, ibid.; Murray, op. cit., p. 73; and Shirley & Adams, op. cit., p. 268. |

| 8 | John Tittensor, quoted in Lumby, op. cit., pp. 23–4. |

| 9 | Sandra Hall, quoted in Lumby, ibid., p. 23. |

| 10 | Goldsmith, Ward & O’Regan, op. cit., p. 123. |

| 11 | Vieth & Moran, op. cit., p. 53. |

| 12 | Tom O’Regan, ‘Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1989, p. 76. |

| 13 | Vieth & Moran, op. cit., p. 53. |

| 14 | ibid., p. 83. |

| 15 | ibid. |

| 16 | Murray, op. cit., p. 73. |

| 17 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 15. |

| 18 | ibid., p. 18. |

| 19 | ibid., p. 20. |

| 20 | ibid., p. 18. |

| 21 | Michelle Arrow, Friday on Our Minds: Popular Culture in Australia Since 1945, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009, p. 114. |

| 22 | Albert Moran & Errol Vieth, Film in Australia: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2006, p. 62. |

| 23 | O’Regan, op. cit., p. 85. |

| 24 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 21. |

| 25 | Shirley & Adams, op. cit., p. 268. |

| 26 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 22. |

| 27 | ibid. |

| 28 | ibid., pp. 31, 30. |

| 29 | ibid., pp. 3–4. |

| 30 | Susan Magarey, Dangerous Ideas: Women’s Liberation – Women’s Studies – Around the World, The University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide, 2014, pp. 23–4. |

| 31 | ibid., p. 24. |

| 32 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 26. |

| 33 | O’Regan, op. cit., pp. 85–6. |

| 34 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 35 | ibid., p. 25. |

| 36 | ibid. |

| 37 | Murray, op. cit., p. 73. |

| 38 | O’Regan, op. cit., p. 86. |

| 39 | ibid. |

| 40 | ibid. |

| 41 | See, for example, Straightheads (Dan Reed, 2007), The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Niels Arden Oplev, 2009; David Fincher, 2011), and Steven R Monroe’s 2010 remake of Meir Zarchi’s 1978 exploitation classic I Spit on Your Grave. |

| 42 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 27. |

| 43 | ibid., p. 25. |

| 44 | ibid., p. 28. |

| 45 | John Carney, ‘“A Generalised Campaign Against All Australian Men”: Mark Latham Attacks Australian of the Year Rosie Batty on Triple M for Her Work Opposing Domestic Violence’, Daily Mail, 22 January 2016, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3411207/Mark-Latham-attacks-Rosie-Batty-s-domestic-violence-campaign-Triple-M-radio-show.html>, accessed 11 November 2016. |

| 46 | ‘Mark Latham: Former Labor Leader Says Domestic Violence a “Coping Mechanism” for Men’, ABC News, 22 January 2016, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-01-22/mark-latham-under-fire-for-triple-m-podcast-domestic-violence/7107650>, accessed 11 November 2016. |

| 47 | In 2010, in light of a scandal surrounding a woman’s allegations of sexual assault against a Collingwood Football Club player, Peter ‘Spida’ Everitt notoriously tweeted: ‘At 3am when you are blind drunk & you decide to go home with a guy ITS NOT FOR A CUP OF MILO!’; see Thomas Hunter & Will Brodie, ‘“Spida” Turns on Women over Collingwood Sex Allegations’, The Age, 5 October 2010, <http://www.theage.com.au/afl/afl-news/spida-turns-on-women-over-collingwood-sex-allegations-20101005-1659d.html>, accessed 11 November 2016. |

| 48 | Lumby, op. cit., p. 53. |

| 49 | ibid., p. 65. |

| 50 | ibid. |

| 51 | ibid., p. 69. |