‘One little movie (budget about [A]$100,000) shouldn’t have to carry a responsibility so completely external to its own nature and potential appeal. But it does.’

– Sylvia Lawson, The Canberra Times[1]Sylvia Lawson, ‘Melbourne Premiere of First All-Australian Feature Film in 10 Years: Director’s Lyric Design Realised’, The Canberra Times, 28 March 1969, p. 16.

In early 1969, a group of film critics boarded an Italian ocean liner docked in Port Melbourne to see a new movie from Columbia Pictures.[2]See Richard Campbell, ‘The High-minded Young Australian Observed – Selfconsciously’, The Bulletin, vol. 91, no. 4646, 29 March 1969, p. 42. This was an Australian film that the studio hoped would emerge as a major release, at a time when the conventional wisdom held that there was no audience for local production.[3]See ‘The Australian Film?’, Current Affairs Bulletin, December 1967; and Mike Thornhill, ‘How Can You Like What You Haven’t Seen?’, The Australian, 10 October 1970. In both articles, Thornhill outlines the previous decade’s business conventions and traditions that, he argues, obstructed the evolution of feature film practice in Australia. Columbia believed their fresh acquisition, 2000 Weeks (Tim Burstall, 1969) – a downbeat romantic drama, in the ‘European’ style – might have a chance to break out of what local wits called the ‘corduroy and claret’ arthouse scene. The marketing push for the film, valued at A$10,000, demonstrated a bold confidence.[4]Accompanying the film’s release was an LP of Don Burrows’ soundtrack; a single of Terry Britten’s title song, ‘2000 Weeks’; and a ‘photo novel’, published in 1968 by Sun Books as Two Thousand Weeks: The Book of the Film by Tim Burstall and Patrick Ryan. According to independent exhibitor Paul Brennan, the A$10,000 marketing spend was excessive for a film of this kind in 1969; see David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1980, pp. 21–33.

Made while there was pressure on the federal government to revive the local feature film industry, moribund since World War II,[5]Giorgio Mangiamele’s Clay, an independent privately financed feature shot in Melbourne with a crew of three, appeared at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. However, since Mangiamele’s film wasn’t strictly speaking intended for general release, nor made by a professional crew, most histories foreground 2000 Weeks as the first Australian feature of its decade. That status, and the promise the latter film represented, was repeated in almost every story published or broadcast about the production leading up to its release. Notable examples included ‘The Flickering Future’, Four Corners, 18 May 1968; Phillip Adams, ‘Facing Fearful Odds’, The Bulletin, vol. 89, no. 4592, 9 March 1968, p. 61; James Hall, ‘Suspense on Celluloid’, The Australian, 11 May 1966, p. 11; and Mike Thornhill, ‘A Cinema of Our Own?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 February 1968. Adams and Hall went as far as to claim it was the first wholly Australian feature in almost twenty years. 2000 Weeks was doomed as an ‘event’: dubbed ‘the first fully professional and fully Australian feature to be completed and released here for a decade’,[6]Lawson, op. cit. it opened not in a small two-hundred seat art house, but at the Forum, a once-grand picture palace in downtown Melbourne, on 27 March 1969.[7]See Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985. ‘2000 Weeks is not the film for which we have desperately hoped,’ wrote The Age’s influential critic Colin Bennett.[8]Colin Bennett, ‘Banality Lets Down Our Great Film Hope’, The Age, 29 March 1969. Bennett and Burstall were friendly acquaintances, but fell out after the review, with the director blaming the critic for damaging the film’s box-office return. Controversy was stirred further when a letter published in The Age on 26 April 1969, written by a Kenneth Newcombe, declared that the exhibitors were the true villains for pulling the film. Burstall believed that the letter was written by Bennett, a claim the critic has always denied. Mike Thornhill in The Australian wasn’t much more enthusiastic: ‘Here then was to be a [ninety-minute] Australian feature film in which there wasn’t a kangaroo or koala in sight; a cross between A Man and a Woman [Claude Lelouch, 1966]and The Graduate [Mike Nichols, 1967] […] It fails to grip.’[9]Mike Thornhill, ‘Issues Raised – Verbally’, The Australian, 29 March 1969. The film’s theatrical run lasted just eleven days; later, at a screening at that year’s Sydney Film Festival, punters booed and heckled the picture.[10]Burstall and lead actress Jeanie Drynan were present at the screening, with the latter reportedly fleeing in tears. See Cathy Hope & Adam Dickerson, ‘“Give It a Go You Apes”: Relations Between the Sydney and Melbourne Film Festivals, and the Early Australian Film Industry (1954–1970)’, Screening the Past, issue 30, April 2011, available at <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-30-first-release/%E2%80%98give-it-a-go-you-apes%E2%80%99-relations-between-the-sydney-and-melbourne-film-festivals-and-the-early-australian-film-industry-1954%E2%80%931970/>, accessed 17 May 2021.

The impact of 2000 Weeks’ failure on Burstall’s career was instant. His production company, Eltham Films, was dissolved after co-founder Patrick Ryan – who had worked with Burstall for the better part of the decade, producing more than twenty of the director’s shorts starting with The Prize (1960) and going on to co-write and co-produce 2000 Weeks – left the business, having contributed a substantial portion of his personal fortune to the film’s budget. Yet, ten years later, Burstall had become the most prolific and commercially successful filmmaker of Australia’s ‘film renaissance’. His hit films of the 1970s – Stork (1971), Alvin Purple (1973) and Petersen (1974) among them – were hardly critics’ favourites, and were routinely dismissed as crude entertainment at best, crass commercialism at worst.[11]See Stratton, op. cit.; and Graeme Blundell, ‘Memoirs of a Sexual Rebel, Faded Emblem of an Age’, The Australian, 17 February 2012, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/memoirs-of-a-sexual-rebel-faded-emblem-of-an-age/news-story/f4abc35baa2288cb44d8fb9320a1efec>, accessed 14 May 2021. For those who remembered 2000 Weeks at all, these works seemed a betrayal of the earlier high-minded ambitions of Burstall, Ryan and their colleagues. Burstall credited the fate of 2000 Weeks as the catalyst for the dramatic change in his artistic direction, and, in the years that followed, stoked its reputation as an unqualified disaster.[12]Burstall explains that the budget derived from a 45 per cent split in the partnership between principals Eltham Films and Senior Films, along with a 10 per cent contribution from the Victorian Film Labs; the filmmakers split the marketing cost fifty-fifty with Columbia. See Scott Murray, ‘Tim Burstall’, Cinema Papers, no. 23, September–October 1979, p. 493. Whatever view one takes on the film’s cinematic merits,[13]Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper point out that not all of the reviews were bad: British critic Dilys Powell expressed admiration for the film’s ‘sincerity’ in The Sunday Times, and a screening at the 1969 Moscow Film Festival was well received. See Pike & Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, rev. edn, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1998 [1980], p. 244. revisiting the moment of 2000 Weeks reveals much about the unique challenge of making an Australian film at the end of the 1960s.

Story and production

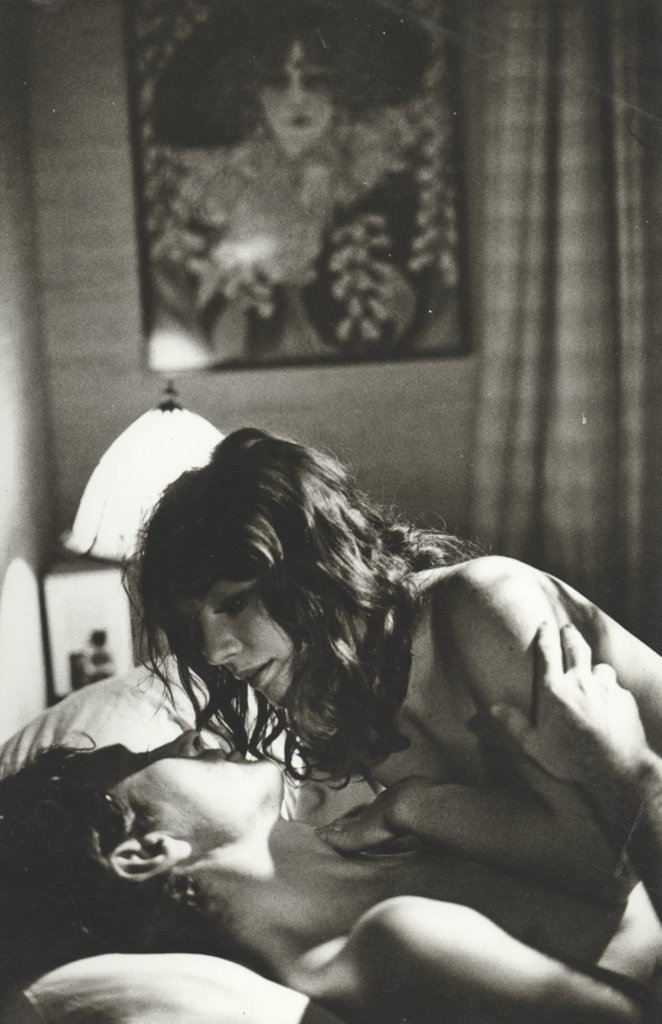

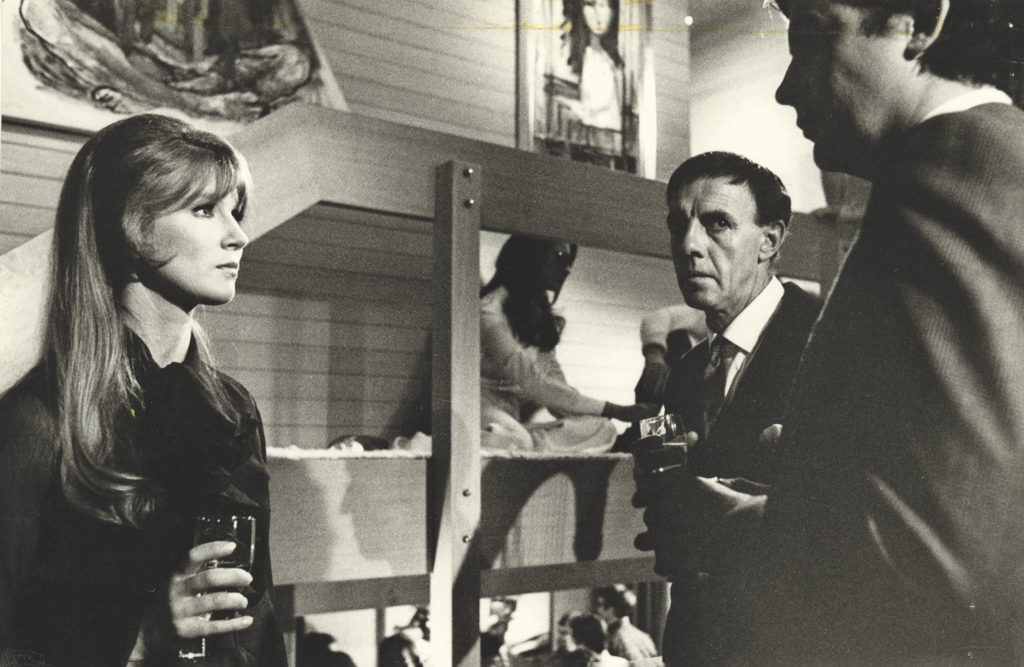

2000 Weeks is the story of a young man’s existential dread. At thirty, Will (Mark McManus) is a journalist torn up over his love life and career. His open marriage with Sarah (Eileen Chapman) has lost its emotional authenticity. Jacky (Jeanie Drynan), his girlfriend, is leaving for London, and his dad (Michael Duffield) has been given a week to live. Will contemplates fleeing from all of it – perhaps overseas – so that he can pursue his ambition of writing a novel, but his situation is thrown into high relief when an old school pal, Noel (David Turnbull), who is now a successful expat living in London, arrives in Melbourne to make a documentary about Australia. Will listens with growing impatience but the ostensible tolerance of a saint to Noel’s lengthy monologues at the expense of his home country: about its suspicion of artists, its open hostility to intellectuals.[14]Fleeing the country, usually for England, was a middle-class rite of passage for multiple generations of Australians with artistic inclinations; famous expats of a slightly younger group than Burstall, including Clive James, Bruce Beresford, Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Barry Humphries, produced a virtual cottage industry in memoirs chronicling the Down Under of the 1950s or thereabouts as a ‘cultural desert’. See Ian Britain, ‘Barry Humphries and the “Feeble Fifties”’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 27, no. 109, October 1997, p. 6. ‘I associate [Australia] with all the things I wanted to escape from when I left,’ Noel says. ‘The hideous provincial attitudes of everyone, the awful mediocrity. To me, Australia always seemed a nation without a mind.’

Burstall’s film is episodic to the point that certain story elements feel like non sequiturs. Yet some of this action is crucial to its ideas.

Burstall’s film is episodic to the point that certain story elements feel like non sequiturs (a quality that proved a bête noire for its critics). Yet some of this action is crucial to its ideas. Early on, Will learns that he has an opportunity to write teleplays. The publisher of his newspaper, involved in TV network broadcasting, is branching into producing local drama – something of an innovation, since most programming of the time was imported.[15]See Graham Shirley & Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, rev. edn, Currency Press, Woollahra, NSW, 1989 [1983], p. 189. This bit of plot is given next to no screen time (though it does help trigger the film’s climactic fistfight; more on that later.)

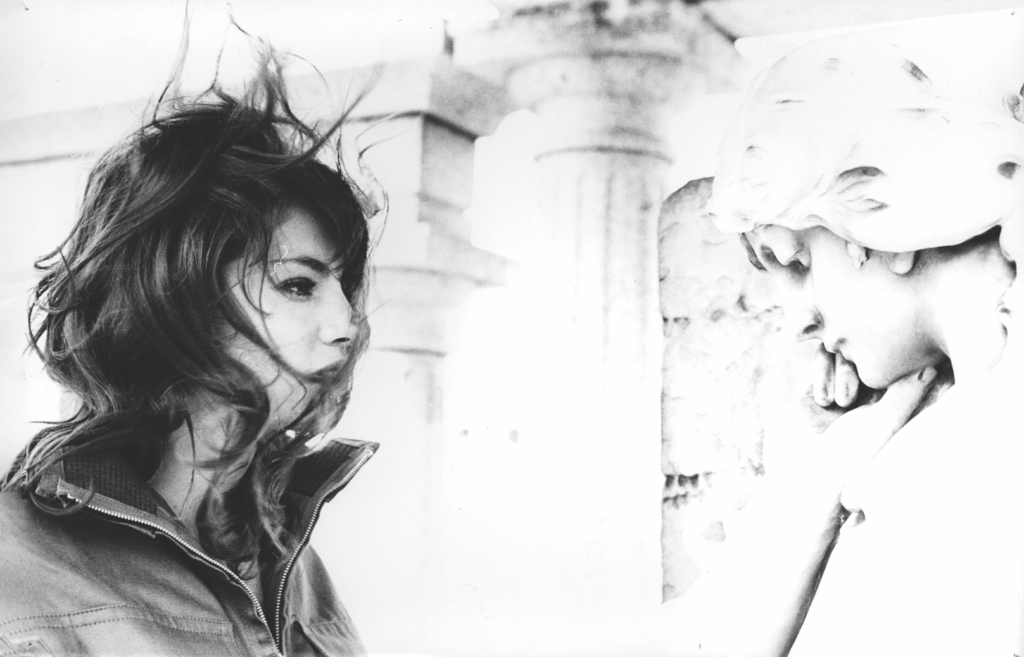

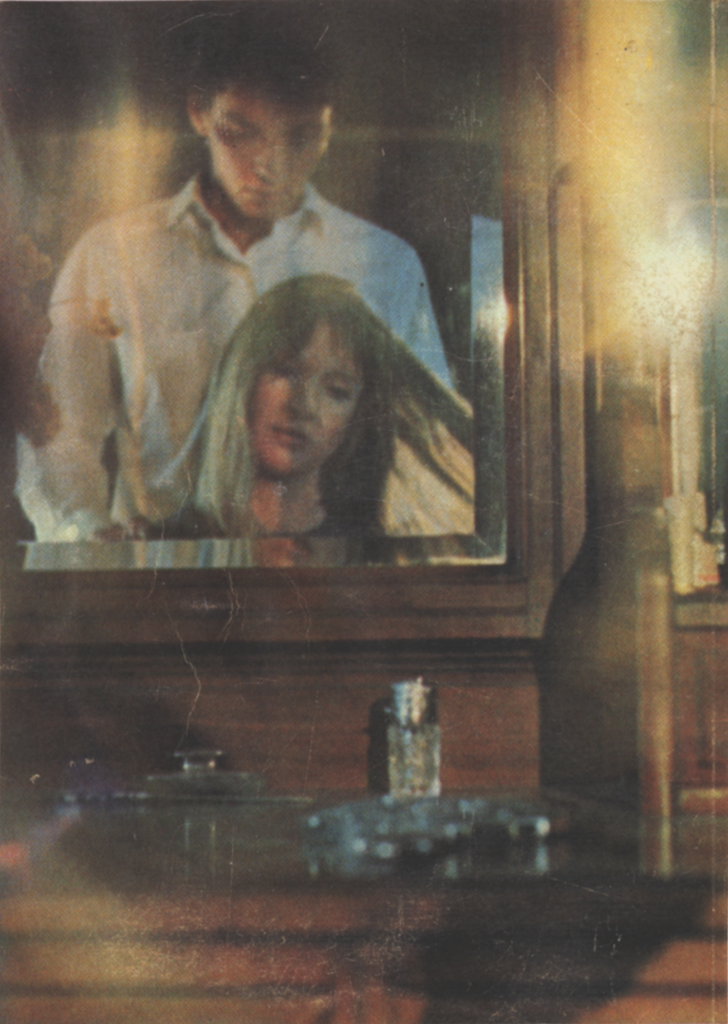

Threaded throughout 2000 Weeks is a series of what Burstall called ‘Felliniesque’[16]Burstall’s crack about Fellini was typical of a personality given to flippant shorthand that can sound pretentious in print but was primarily aimed at pithiness; in short, there is no whiff of surrealism in 2000 Weeks. To conserve space, I have elected not to deal closely with the materiality of the film – its sound, image and mise en scène – but it’s worth noting that Burstall and his collaborators divide the ‘past’ from the ‘present’ by mobilising simple techniques: wide lens, high contrast, soft focus and/or ’extreme’ angles for the flashbacks, and more subtle shades of contrast, observational eye-level compositions and occasional expressive point-of-view shots for the present. flashbacks – crucial moments in Will’s past, through childhood, adolescence and early marriage – that feed his present-day emotional crisis as reminders of old wounds, unresolved quarrels and simpler, more innocent times. The film attracted praise for its performances, but not for its characterisations. Will’s almost superhuman ability to withstand every emotional issue – with nothing more than inscrutable handsomeness and the distracted air of someone with important things on his mind – drew stinging rebukes. Critic Paul Byrnes writes of Will that ‘his passivity is partly the fashion – European cinema was full of young artistic men in existential crises, in films like Blow Up [Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966]’.[17]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘2000 Weeks’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/2000-weeks/notes/>, accessed 17 May 2021. Burstall, for his part, talked about the influence of Ingmar Bergman, but some critics (like Thornhill, who otherwise praised Robin Copping’s cinematography[18]Thornhill, ‘Issues Raised’, op. cit.) felt that 2000 Weeks’ mood was romantic, emphasising beauty for its own sake. The film is, crudely put, ‘realist’, but the quotidian never really intrudes; the settings feel abstract, or self-consciously ‘poetic’ (for instance, Will and Jacky discuss their dissolving relationship in a graveyard). Most commentators have positioned 2000 Weeks rather unhelpfully as an imitation European ‘art movie’ – a romantic melodrama in the manner of, say, Lelouch. The film’s mystique, however, was founded a very long way from Deauville.[19]One of the key settings of Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman.

Development and thematic concerns

2000 Weeks began development soon after Burstall and his family had returned from the United States, where the director had studied acting and filmmaking on a Harkness Fellowship.[20]While in the US, Burstall made several films, studied at the Actors Studio and got an attachment on Hombre (Martin Ritt, 1967). As a rule, he told me, he favoured ‘actor management’ as the principal role of the director, and subordinated a lot of ‘technique’ to the camera department. Ryan and Burstall had been trying to make a feature since 1960. ‘There was a feeling that filmmaking was not for us, meaning Australians,’ Burstall recounted in 2003.[21]Tim Burstall, interview with author, 2003. While researching this piece, the author also drew upon previous personal interviews conducted over the years with Adams, Betty Burstall, Rod Bishop, Drynan, John Flaus, Geoff Gardner, John B Murray, Scott Murray, Pike, Stratton and Thornhill, as well as the 2000 Weeks cast and crew interviews available in the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia’s Oral History collection. ‘The government saw itself as having no role,’ he observed previously, in an interview in Cinema Papers. ‘The major distributors were unable to return money on any of the few films that had been made […] The few Australian features which had been released had given the industry a very bad image.’[22]Tim Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 492. Here, Burstall might be thinking of British–Australian co-production They’re a Weird Mob (Michael Powell, 1966) and American–Australian co-production Journey out of Darkness (James Trainor, 1967). Thornhill backed up this characterisation of the low regard in which the industry was held in the 1960s: ‘Filmmaking was not seen as “culture”; it was seen as pap made by technicians and paid for by businessmen.’[23]Mike Thornhill, interview with author, circa 2003.

Burstall, for his part, talked about the influence of Ingmar Bergman, but some critics felt that 2000 Weeks’ mood was romantic, emphasising beauty for its own sake.

While still in the US, Burstall met with an executive from United Artists who advised on the best path to getting a feature up in Australia – he paraphrased the counsel he received as: ‘Make something for the international arthouse market, because the most you’ll get back in the local market is [A]$50,000.’[24]Burstall, interview with author, op. cit. Burstall and Ryan formulated a production model based on Bergman’s low-budget enterprises: a shooting schedule of eleven weeks, practical locations, a small cast, a crew of fourteen and a budget of A$100,000. Over a period of several weeks, Ryan and Burstall met regularly and recorded the sessions on tape; they mapped out story situations, characters and ideas. Then Burstall, working alone, composed the script, while Ryan and associate producer John B Murray raised finance and worked on the contingencies.

For the film’s theme, Burstall and Ryan elected to focus on adultery, a subject the director was intimately familiar with.[25]It should be noted that certain aspects of the film are drawn from Ryan’s life as much as its director’s: for instance, unlike Burstall, Ryan had worked as a journalist. In the late 1940s, when they were still only in their early twenties, Tim and Betty Burstall settled in Eltham, on Melbourne’s outer rim, which had a reputation at the time as an enclave for progressives; they joined the Communist Party and began leading an open marriage. ‘Follow your lust,’ Burstall recounted, of the prevailing philosophy of the moment, ‘but don’t fall in love.’[26]Burstall, interview with author, op. cit. This situation becomes Will’s dilemma with his wife and his lover in 2000 Weeks.[27]In 1954, Burstall expended many of his waking hours in a romantic pursuit of nineteen-year-old university student Julia Fay Rosefield; more than one scene in 2000 Weeks seems inspired by the tensions this relationship created in his marriage, friendships and peer group (as well as those of Rosefield, who later rose to prominence as poet Fay Zwicky), though sources close to Burstall have told me the film’s narrative more reflected a personal situation occurring in the decade that followed the diaries. See Blundell, op. cit.

In November 1953, at twenty-six, Burstall began a journal from which he hoped would emerge ‘the Great Australian Novel’ (an ambition that Will, too, inherited). He called his diary ‘The Memoirs of a Young Bastard Who Sunbaked and Rooted and Went to Branch Meetings’.[28]Burstall’s various papers, including his complete and unedited diaries from 1953 to 1956, are collected at the State Library of Victoria. A section of the diary was later published in 2012; in its introduction, Hilary McPhee writes, ‘The Burstall diaries were written against the backdrop of an Australia easily caricatured as dull and provincial, straitjacketed by suburban convention and communist paranoia.’ McPhee, ‘About the Burstall Diaries’, in Tim Burstall, Memoirs of a Young Bastard: The Diaries of Tim Burstall, November 1953 to December 1954, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic., 2012, pp. IX–X. From its very first entry, Burstall and Ryan found the title of the film: ‘two thousand weeks’ was a catchphrase among the director’s pals referring to their perception that, upon reaching the age of thirty, forty years was all the time anyone had left to realise their ambitions, to find themselves in their work or to discover whatever it was that was important. For Burstall, it seemed no time at all.[29]Burstall, ibid.

The diaries help to reimagine 2000 Weeks’ ambitions as something quite alive and visceral rather than abstract, without excusing the film’s flaws. This is particularly true of the film’s major set piece, reminiscent of the cruel gamesmanship of what Burstall calls his ‘tribe’. This is where Noel challenges Jacky and Sarah to an ‘honesty test’. He goads the pair into declaring the reality of their emotional lives with Will; for Noel, their mutual embarrassment exposes the limits of their ‘liberalism’.

Burstall privately conceded that he was offering a brutal self-assessment with both the Will and Noel characters, an essay on the limits of courage masked in self-indulgence (he fought shy of assertions of latent misogyny).[30]Burstall, interview with author, op. cit.; the male principals in 2000 Weeks are unreconstructed sexists who treat the women they are involved with with a certain amount of contempt, something that disturbed viewers at the time. Publicly, he felt the love triangle baffled ‘a general audience’, apportioning prevailing morality as one cause of the film’s commercial failure: ‘If the characters had been deceiving each other, and not openly declaring their relationships, it probably would have met with greater acceptance,’ he said in 1979. ‘It may have been all right in a French film, but not in an Australian [one].’[31]Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 495.

The new nationalism

AA Phillips’ essay ‘The Cultural Cringe’[32]AA Phillips, ‘The Cultural Cringe’, Meanjin, vol. 9, no. 4, Summer 1950, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/the-cultural-cringe-by-a-a-phillips/>, accessed 17 May 2021. appeared in Meanjin in 1950, soon after then–prime minister Robert Menzies’ conservative Liberal–Country Party coalition was first elected to office. ‘Phillips wished to create a national culture that conceded no inferiority to Britain,’ explains historian Rollo Hesketh, ‘and indeed was unembarrassed to be Australian.’[33]Rollo Hesketh, ‘A.A. Phillips and the “Cultural Cringe”: Creating an “Australian Tradition”’, Meanjin, vol. 72, no. 3, 2013, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/a-a-phillips-and-the-icultural-cringei-creating-an-iaustralian-traditioni/>, accessed 17 May 2021.

Phillips’ piece – which, it should be noted, was not discussing the production of art (specifically literature) but its reception[34]I’m indebted to Ian Anderson for this point; see Anderson, ‘“Freud Has a Name for It”: A.A. Phillips’s “The Cultural Cringe”’, Southerly, vol. 69, no. 2, January 2009, pp. 127–47. – made an impression on Burstall; in the diaries, he finds himself defending Australia’s cultural potential and reality against men and women who sound a lot like Noel (such as Clive James, who notoriously referred to the country as ‘a mysterious triangle in the South Pacific where talent disappears’[35]Clive James, quoted in Kenneth Minogue, ‘Cultural Cringe: Cultural Inferiority Complex and Republicanism in Australia’, National Review, vol. 47, no. 25, 31 December 1995, p. 21.). The climactic punch-up between Noel and Will fuses sex and cultural ‘cringe’: Noel has slept with Jacky, called her a whore, and made certain that Will won’t get a job on the new TV show, with its English producers expressing no interest in breaking in new Australian talent; Will responds by punching Noel in the face. Burstall encouraged an interpretation here of ‘cultural commentary’.[36]This scene may be loosely autobiographical; Burstall told me that he got involved in fistfights ‘at least one a year’ until he was forty.

On 1 November 1967, then–prime minister Harold Holt announced the creation of the Australia Council for the Arts: an extraordinary policy reversal that met with widespread approval in the media.[37]I am indebted to Stuart Ward for his superb gloss on the moment of Australia’s ‘new nationalism’ from circa 1967 to 1972. See Ward, ‘“Culture up to Our Arseholes”: Projecting Post-imperial Australia’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 51, no. 1, March 2005, p. 55. What Burstall and his collaborators were satirising as complacency and cultural suffering in 2000 Weeks had given way to a fresh confidence. This was further bolstered by a speech by Holt’s successor, John Gorton, on 26 January 1968 – shortly after 2000 Weeks began shooting – in which he stated that ‘national development’ was a priority, an approach that was later dubbed ‘the new nationalism’.[38]See ‘We’re Not That Much All Right, John’, The Bulletin, vol. 89, no. 4587, 3 February 1968, p. 11. Embedded in this idea was a program to support the arts, including film, an ambition that Gough Whitlam’s incoming government enthusiastically embraced when it came to power in 1972.[39]See Ward, op. cit. By 1973, the mood had turned gleeful. Filmmakers’ sweet relief mixed with an air of – perhaps deserved – self-congratulation as suburban audiences flocked to see Australian-made hit films and production surged.[40]Pike and Cooper provide some helpful insights on three films that ‘proved’ to exhibitors that there was, after all, an audience for Australian films: Stork, The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (Bruce Beresford, 1972) and Alvin Purple. See Pike & Cooper, op. cit., pp. 262, 265, 274.

At this point, 2000 Weeks – a film whose published screenplay was ‘dedicated to the future of the Australian film industry’ – had mostly been forgotten, already consigned to more or less where it sits today in the Australian cinema canon: as an outlier and a relatively obscure footnote (to this day, the film has never been available on any home-release format, and public screenings are rare[41]Three short clips from the film are available on the film’s Australian Screen page; see ‘2000 Weeks’, op. cit.). It is possible to exaggerate the significance of what critics saw as the esoteric intellectual pretensions of the film as the key to its ‘failure’, but any review of the contemporary criticism reveals an overall frustration with it as narrative and as cinema. Burstall – whose focus thereafter would be dedicated to crafting a unique vernacular for the local mainstream and building a business, as much as a career – took this last point to heart: ‘I asked actors to act unactable things,’ he said in 1979, ‘and say unsayable things.’[42]Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 493.

The future of the industry was indeed bright in the immediate years that followed 2000 Weeks’ release: 120 films were made here between 1970 and 1980, and the institutional support for the arts was, in the country’s short post-settlement history, unprecedented. It was a time that satirists, nonetheless, thought ripe for mocking. At the pictures, Will’s earnest hope for a new nationalism had morphed into the spectacular overconfidence of Barry ‘Bazza’ McKenzie (Barry Crocker). Turning his gaze upon the Old World of Europe in Barry McKenzie Holds His Own (Bruce Beresford, 1974), the titular larrikin sees no promise: ‘Don’t let this clapped-out culture grab you, mate,’ Bazza tells an expat friend. ‘I mean, back in Oz now we’ve got culture up to our arseholes.’

Special thanks to Chris McCullough, who originally commissioned me to research and write a series about the Australian new wave twenty years ago, and to all the interviewees; and fond thanks to the Burstall and Ryan families and Tony Buckley. Thanks, too, to all at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, especially Simon Drake. Personal thanks to Pamela Talty.

Endnotes

| 1 | Sylvia Lawson, ‘Melbourne Premiere of First All-Australian Feature Film in 10 Years: Director’s Lyric Design Realised’, The Canberra Times, 28 March 1969, p. 16. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Richard Campbell, ‘The High-minded Young Australian Observed – Selfconsciously’, The Bulletin, vol. 91, no. 4646, 29 March 1969, p. 42. |

| 3 | See ‘The Australian Film?’, Current Affairs Bulletin, December 1967; and Mike Thornhill, ‘How Can You Like What You Haven’t Seen?’, The Australian, 10 October 1970. In both articles, Thornhill outlines the previous decade’s business conventions and traditions that, he argues, obstructed the evolution of feature film practice in Australia. |

| 4 | Accompanying the film’s release was an LP of Don Burrows’ soundtrack; a single of Terry Britten’s title song, ‘2000 Weeks’; and a ‘photo novel’, published in 1968 by Sun Books as Two Thousand Weeks: The Book of the Film by Tim Burstall and Patrick Ryan. According to independent exhibitor Paul Brennan, the A$10,000 marketing spend was excessive for a film of this kind in 1969; see David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1980, pp. 21–33. |

| 5 | Giorgio Mangiamele’s Clay, an independent privately financed feature shot in Melbourne with a crew of three, appeared at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. However, since Mangiamele’s film wasn’t strictly speaking intended for general release, nor made by a professional crew, most histories foreground 2000 Weeks as the first Australian feature of its decade. That status, and the promise the latter film represented, was repeated in almost every story published or broadcast about the production leading up to its release. Notable examples included ‘The Flickering Future’, Four Corners, 18 May 1968; Phillip Adams, ‘Facing Fearful Odds’, The Bulletin, vol. 89, no. 4592, 9 March 1968, p. 61; James Hall, ‘Suspense on Celluloid’, The Australian, 11 May 1966, p. 11; and Mike Thornhill, ‘A Cinema of Our Own?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 February 1968. Adams and Hall went as far as to claim it was the first wholly Australian feature in almost twenty years. |

| 6 | Lawson, op. cit. |

| 7 | See Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), An Australian Film Reader, Currency Press, Sydney, 1985. |

| 8 | Colin Bennett, ‘Banality Lets Down Our Great Film Hope’, The Age, 29 March 1969. Bennett and Burstall were friendly acquaintances, but fell out after the review, with the director blaming the critic for damaging the film’s box-office return. Controversy was stirred further when a letter published in The Age on 26 April 1969, written by a Kenneth Newcombe, declared that the exhibitors were the true villains for pulling the film. Burstall believed that the letter was written by Bennett, a claim the critic has always denied. |

| 9 | Mike Thornhill, ‘Issues Raised – Verbally’, The Australian, 29 March 1969. |

| 10 | Burstall and lead actress Jeanie Drynan were present at the screening, with the latter reportedly fleeing in tears. See Cathy Hope & Adam Dickerson, ‘“Give It a Go You Apes”: Relations Between the Sydney and Melbourne Film Festivals, and the Early Australian Film Industry (1954–1970)’, Screening the Past, issue 30, April 2011, available at <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-30-first-release/%E2%80%98give-it-a-go-you-apes%E2%80%99-relations-between-the-sydney-and-melbourne-film-festivals-and-the-early-australian-film-industry-1954%E2%80%931970/>, accessed 17 May 2021. |

| 11 | See Stratton, op. cit.; and Graeme Blundell, ‘Memoirs of a Sexual Rebel, Faded Emblem of an Age’, The Australian, 17 February 2012, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/memoirs-of-a-sexual-rebel-faded-emblem-of-an-age/news-story/f4abc35baa2288cb44d8fb9320a1efec>, accessed 14 May 2021. |

| 12 | Burstall explains that the budget derived from a 45 per cent split in the partnership between principals Eltham Films and Senior Films, along with a 10 per cent contribution from the Victorian Film Labs; the filmmakers split the marketing cost fifty-fifty with Columbia. See Scott Murray, ‘Tim Burstall’, Cinema Papers, no. 23, September–October 1979, p. 493. |

| 13 | Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper point out that not all of the reviews were bad: British critic Dilys Powell expressed admiration for the film’s ‘sincerity’ in The Sunday Times, and a screening at the 1969 Moscow Film Festival was well received. See Pike & Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977, rev. edn, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1998 [1980], p. 244. |

| 14 | Fleeing the country, usually for England, was a middle-class rite of passage for multiple generations of Australians with artistic inclinations; famous expats of a slightly younger group than Burstall, including Clive James, Bruce Beresford, Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Barry Humphries, produced a virtual cottage industry in memoirs chronicling the Down Under of the 1950s or thereabouts as a ‘cultural desert’. See Ian Britain, ‘Barry Humphries and the “Feeble Fifties”’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 27, no. 109, October 1997, p. 6. |

| 15 | See Graham Shirley & Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, rev. edn, Currency Press, Woollahra, NSW, 1989 [1983], p. 189. |

| 16 | Burstall’s crack about Fellini was typical of a personality given to flippant shorthand that can sound pretentious in print but was primarily aimed at pithiness; in short, there is no whiff of surrealism in 2000 Weeks. To conserve space, I have elected not to deal closely with the materiality of the film – its sound, image and mise en scène – but it’s worth noting that Burstall and his collaborators divide the ‘past’ from the ‘present’ by mobilising simple techniques: wide lens, high contrast, soft focus and/or ’extreme’ angles for the flashbacks, and more subtle shades of contrast, observational eye-level compositions and occasional expressive point-of-view shots for the present. |

| 17 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘2000 Weeks’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/2000-weeks/notes/>, accessed 17 May 2021. |

| 18 | Thornhill, ‘Issues Raised’, op. cit. |

| 19 | One of the key settings of Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman. |

| 20 | While in the US, Burstall made several films, studied at the Actors Studio and got an attachment on Hombre (Martin Ritt, 1967). As a rule, he told me, he favoured ‘actor management’ as the principal role of the director, and subordinated a lot of ‘technique’ to the camera department. |

| 21 | Tim Burstall, interview with author, 2003. While researching this piece, the author also drew upon previous personal interviews conducted over the years with Adams, Betty Burstall, Rod Bishop, Drynan, John Flaus, Geoff Gardner, John B Murray, Scott Murray, Pike, Stratton and Thornhill, as well as the 2000 Weeks cast and crew interviews available in the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia’s Oral History collection. |

| 22 | Tim Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 492. Here, Burstall might be thinking of British–Australian co-production They’re a Weird Mob (Michael Powell, 1966) and American–Australian co-production Journey out of Darkness (James Trainor, 1967). |

| 23 | Mike Thornhill, interview with author, circa 2003. |

| 24 | Burstall, interview with author, op. cit. |

| 25 | It should be noted that certain aspects of the film are drawn from Ryan’s life as much as its director’s: for instance, unlike Burstall, Ryan had worked as a journalist. |

| 26 | Burstall, interview with author, op. cit. |

| 27 | In 1954, Burstall expended many of his waking hours in a romantic pursuit of nineteen-year-old university student Julia Fay Rosefield; more than one scene in 2000 Weeks seems inspired by the tensions this relationship created in his marriage, friendships and peer group (as well as those of Rosefield, who later rose to prominence as poet Fay Zwicky), though sources close to Burstall have told me the film’s narrative more reflected a personal situation occurring in the decade that followed the diaries. See Blundell, op. cit. |

| 28 | Burstall’s various papers, including his complete and unedited diaries from 1953 to 1956, are collected at the State Library of Victoria. A section of the diary was later published in 2012; in its introduction, Hilary McPhee writes, ‘The Burstall diaries were written against the backdrop of an Australia easily caricatured as dull and provincial, straitjacketed by suburban convention and communist paranoia.’ McPhee, ‘About the Burstall Diaries’, in Tim Burstall, Memoirs of a Young Bastard: The Diaries of Tim Burstall, November 1953 to December 1954, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic., 2012, pp. IX–X. |

| 29 | Burstall, ibid. |

| 30 | Burstall, interview with author, op. cit.; the male principals in 2000 Weeks are unreconstructed sexists who treat the women they are involved with with a certain amount of contempt, something that disturbed viewers at the time. |

| 31 | Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 495. |

| 32 | AA Phillips, ‘The Cultural Cringe’, Meanjin, vol. 9, no. 4, Summer 1950, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/the-cultural-cringe-by-a-a-phillips/>, accessed 17 May 2021. |

| 33 | Rollo Hesketh, ‘A.A. Phillips and the “Cultural Cringe”: Creating an “Australian Tradition”’, Meanjin, vol. 72, no. 3, 2013, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/a-a-phillips-and-the-icultural-cringei-creating-an-iaustralian-traditioni/>, accessed 17 May 2021. |

| 34 | I’m indebted to Ian Anderson for this point; see Anderson, ‘“Freud Has a Name for It”: A.A. Phillips’s “The Cultural Cringe”’, Southerly, vol. 69, no. 2, January 2009, pp. 127–47. |

| 35 | Clive James, quoted in Kenneth Minogue, ‘Cultural Cringe: Cultural Inferiority Complex and Republicanism in Australia’, National Review, vol. 47, no. 25, 31 December 1995, p. 21. |

| 36 | This scene may be loosely autobiographical; Burstall told me that he got involved in fistfights ‘at least one a year’ until he was forty. |

| 37 | I am indebted to Stuart Ward for his superb gloss on the moment of Australia’s ‘new nationalism’ from circa 1967 to 1972. See Ward, ‘“Culture up to Our Arseholes”: Projecting Post-imperial Australia’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 51, no. 1, March 2005, p. 55. |

| 38 | See ‘We’re Not That Much All Right, John’, The Bulletin, vol. 89, no. 4587, 3 February 1968, p. 11. |

| 39 | See Ward, op. cit. |

| 40 | Pike and Cooper provide some helpful insights on three films that ‘proved’ to exhibitors that there was, after all, an audience for Australian films: Stork, The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (Bruce Beresford, 1972) and Alvin Purple. See Pike & Cooper, op. cit., pp. 262, 265, 274. |

| 41 | Three short clips from the film are available on the film’s Australian Screen page; see ‘2000 Weeks’, op. cit. |

| 42 | Burstall, quoted in Murray, op. cit., p. 493. |