In A Place of Greater Safety, Hilary Mantel imagines the following conversation between Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Danton:

‘They talk of a crusade to bring liberty to Europe. Of how it’s our duty to spread the gospel of fraternity.’

‘Spread the gospel? Well, ask yourself – who loves armed missionaries?’

‘Who indeed?’

‘They speak as if they had the interests of the people at heart, but the end of it will be military dictatorship.’[1]Hilary Mantel, A Place of Greater Safety, Harper Perennial, London, UK, 2007 [1992], p. 398.

The conversation dramatises a real moment in the French Revolution: Robespierre’s passionate opposition to the declaration of war in 1792 by the National Assembly on nearly all the countries of Europe. Robespierre was not averse to more than a touch of messianic zeal himself, but he could see the danger of a fervent idealism that fails to take into account the needs and desires of those it professes to serve. And he was prescient: the revolutionary wars morphed into the Napoleonic wars, which temporarily resulted in Napoleon’s siblings and acolytes ruling as the crowned heads of Europe.

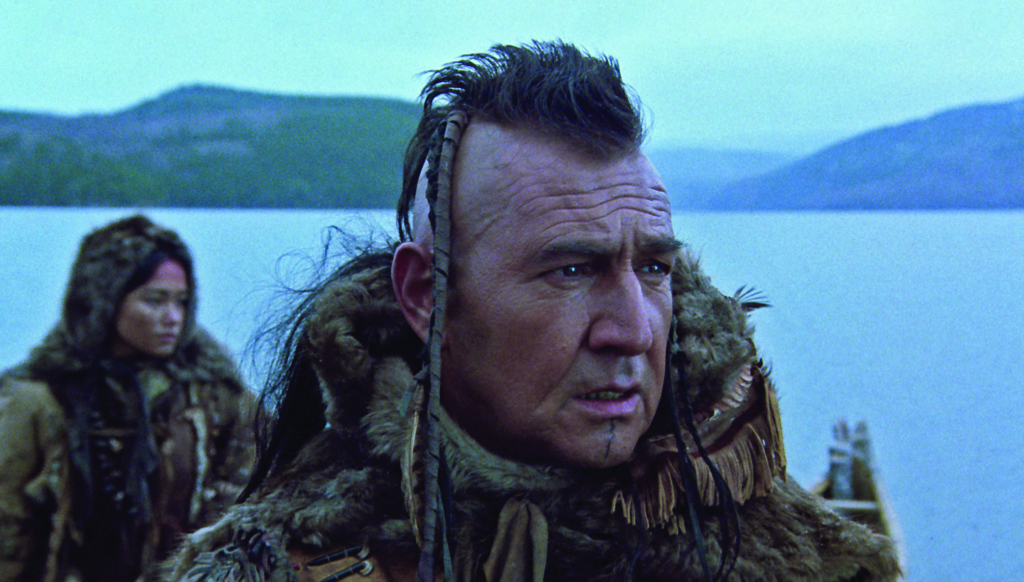

Missionaries, of course, come in guises other than armed foot soldiers of revolutionary governments, and with weapons other than swords and muskets. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the work of Christian missionaries throughout the centuries who, sometimes following in the footsteps of imperial colonisers, sometimes forging their own paths in foreign lands, sought to convert and ‘civilise’ the ‘barbarians’ of these worlds. ‘Soldiers of heaven’, Champlain (Jean Brousseau), the commandant of Quebec, calls the Jesuits as he introduces them to the Algonquins, who will escort the major protagonist of Black Robe (Bruce Beresford, 1991), Father Laforgue (Lothaire Bluteau), on his river journey of 1500 kilometres to the isolated Jesuit mission at Ihonatiria. His weaponry? His own religious fervour, and a promise of ‘Paradise’.

The history of Christian conversion is one rich in dramatic possibilities. In Roland Joffé’s The Mission (1986), for example, the two missionaries, played by Jeremy Irons and Robert De Niro, come across like precursors of twentieth-century Marxist liberation-theology priests, taking up arms in sympathy with the native population against the colonising powers, including the hierarchy of their own church. The mesmerising Ennio Morricone score holds in tension, especially in the closing sequence, a rousing celebration of Native American life intermixed with the nobility of the missionaries’ actions, and an elegiac sense of the impending doom of both.

In Martin Scorsese’s more austere and meditative Silence (2016), Father Rodrigues’ (Andrew Garfield) ‘dark night of the soul’, a compound of physical privation and psychological torture, is made more agonising when he finally meets the ‘Colonel Kurtz’ of his spiritual journey, the apostate Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson). The horror is not so much the latter’s apostasy as the fact that Ferreira agrees with his Japanese captors that Japanese society and culture are barren grounds for a conversion to Christianity.

‘Fear, hostility and despair’

For Brian Moore, the scriptwriter of Black Robe as well as author of the book from which it was adapted, the dramatic possibilities of the narratives of Christian conversion in the early history of Canada were threefold. Two of them he found in his wideranging research into the period. He read extensively on the history of the Jesuits in Canada, beginning with Francis Parkman’s magisterial The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century, which he first became aware of in a Graham Greene essay, before turning to the primary sources inRelations, the voluminous collection of letters the Jesuit missionaries sent back to their superiors in France.

The first of these was the temperament of his protagonist, Father Laforgue, which he drew from the portrait of a Father Chaband, who found so much of the Indian culture and lifestyle – their bodily functions and food, as well as what he saw as their squalor, promiscuity, barbaric cruelty, living in the moment and oppressive communality that allowed little space for privacy – antipathetic, even repelling; yet he made a ‘solemn vow’ to live among them and serve them for the rest of his life. The second was a growing disquiet regarding what, in his view, the research revealed about the irreconcilable differences between the two cultures:

I was made doubly aware of the strange and gripping tragedy that occurred when the Indian belief in a world of night and in the powers of dreams clashed with the Jesuits’ preachments of Christianity and a paradise after death. This novel is an attempt to show that each of these beliefs inspired in the other fear, hostility, and despair.[2]Brian Moore, ‘Author’s Note’, Black Robe, Head of Zeus, London, UK, 2017 [1983], p. xix.

To these, one might add the ridicule and scorn with which First Nations characters view Laforgue: his unwillingness to share his possessions, his chastity, his losing his way in the forest. To the children, he is a figure of bemusement, as they pluck his sparse beard and play a kind of seventeenth-century frisbee with his broad-brimmed hat.

These irreconcilable differences are given dramatic potency in Moore’s script in the developing tension between Laforgue’s fervour for his mission and the growing respect he develops for the Indians’ beliefs. Running parallel to Laforgue’s growing ambivalence, and in contrast to it, is the story of Daniel (Aden Young), his young French guide, and his trusting acceptance of First Nations culture because of his tenacious, even reckless, love for Annuka (Sandrine Holt), the daughter of the Algonquin chief, Chomina (August Schellenberg). To Daniel, the Indians’ vision of a spirit world present in the natural world makes more rational sense than the Christian vision of Paradise ‘where we all sit on clouds and look at God’. In his eyes, their willingness to share and to forgive makes them more ‘Christian’ in their practice than that of so-called Christians.

The third dramatic possibility for Moore was the product of his determination not to write a historical novel. Instead he found the ‘model’ for his narrative in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and the idea of a spiritual journey, ‘a tale, a journey into an unknown destination, to an unknown ending’.[3]Brian Moore, quoted in Colm Tóibín, ‘Introduction’, in ibid., p. xiii. However, Father Laforgue’s spiritual journey of self-discovery is to an ending that is far more explicit, and more horrifying, than the gnomic utterances of Conrad’s Kurtz. ‘The horror! The horror!’ of Moore’s tale is the bleak recognition in the film’s ‘epitaph’ that the conversion of the Huron tribe to Christianity was a Pyrrhic victory at best, as turning the other cheek made them easy prey for their bitter enemies, the unconverted Iroquois. No wonder critic Roger Ebert sat in the cinema after viewing the film, this ‘bleak and dour affair’, as he calls it, ‘in a state of depressed suspension’.[4]Roger Ebert, ‘Black Robe’, RogerEbert.com, 1 November 1991, <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/black-robe-1991>, accessed 26 May 2020.

A ‘hack plodder’ … not

If Moore’s novel was the catalyst for the film, its actual creation was made possible by the happy conjunction of the following: Bruce Beresford’s tenacity in pursuing the film rights and the chance to direct; the signing of a film co-production agreement between Australia and Canada in 1990; and Samson Productions’ Sue Milliken’s willingness to put her money where her acumen was.

Beresford read the novel on publication and immediately made overtures to Moore directly regarding the film rights, only to discover that they had already been sold in Canada to Robert Lantos, whose Alliance Communications eventually became Canada’s largest independent production house. Beresford offered to direct, but was told that the company had David Cronenberg in mind. That eventually fell through, and the director’s role was offered to Beresford, who suspected his recent success with Driving Miss Daisy (1989) was a key reason for the offer. In addition to that was the knowledge of, and respect for, his growing body of work, including Breaker Morant (1980) and The Fringe Dwellers (1986), films that had been critically and financially successful internationally, despite some stinkers such as King David (1985) – of which Beresford quipped, ‘People walk out of it on aeroplanes. They asked for parachutes so they don’t have to watch it.’[5]Bruce Beresford, quoted in Liz van den Nieuwenhof, ‘What’s Driving Mr Beresford’, Sunday Herald Sun Sunday Magazine, 9 January 2000, p. 9. These were light years away from his earliest feature work, the execrable but now iconic Barry McKenzie films, which, he said, might have sunk his career were it not for the timely intervention of Phillip Adams with an offer to direct a different kind of quintessential Oz film, an adaptation of David Williamson’s play Don’s Party (1976). It may be, too, that Lantos had heard of a fellow producer’s remarks to the critic Michael Sragow that, if you want to make a wilderness film with the explorer as a sort of spiritual adventurer, you ought to get a tough old English director like David Lean or an Australian.[6]Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1992, p. 144.

Beresford once described himself as a ‘hack plodder’[7]Bruce Beresford, quoted in Bruce Domminey, feature on Her Alibi, New Idea, 1 April 1989. when it came to filmmaking. It’s symptomatic of that self-effacing characteristic that led him to reject, in 1996, the Raymond Longford Award. Though flattered, he felt himself too young for a prestigious lifetime-achievement award – prescient, given his body of work in the following twenty-plus years, his most recent being Ladies in Black (2018), a lovely evocation of Sydney in the heyday of the great department stores and the beginnings of a cosmopolitan city life in the presence of a postwar European intellectual diaspora. The fact that Ladies in Black was a project first mooted in the early 2000s is a testimony to Beresford’s patience, as well as his tenacity.

To Daniel, the Indians’ vision of a spirit world present in the natural world makes more rational sense than the Christian vision of Paradise ‘where we all sit on clouds and look at God’.

As for his claim of being a ‘hack plodder’, Beresford’s eclectic and prolific output over a forty-year peripatetic career, his long history of involvement in all aspects of filmmaking (including editing in Nigeria, as well as five years as the inaugural production officer at the British Film Institute’s Production Board), and the testimonies of his film crews and casts belie this. He could be described as a journeyman, perhaps – with more than a touch of professional perfectionism – given his no-nonsense approach to his work and the relative speed with which he moved from one production to another without brooding on success or failure. He is also a confessed workaholic who says, ‘I actually find work enormously relaxing,’[8]Beresford, quoted in van den Nieuwenhof, op. cit., p. 8. though two falls into the icy Saguenay River while filming Black Robe probably tested that sentiment.

Beresford’s co-workers attest to his meticulous planning, complemented by a preparedness for contingencies in his ability to both anticipate and improvise to get the desired effect. Moore said of him: ‘He’s the most intelligent director I’ve ever worked with. He knows exactly what he wants, he’s precise and reasonable and he researches his subject thoroughly in order to get all the details right.’[9]Brian Moore, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, Black Robe press kit, 1991. Peter James, Black Robe’s cinematographer, spoke of Beresford’s generosity in sharing creative decisions, and said of his long working relationship with him, which included television commercials in the 1970s as well as Driving Miss Daisy and Mister Johnson (1990):

Bruce is the only director I’ve worked with whose coverage of a scene is exactly as I’d do it. There’s always a technical sympathy: we tend to agree on just about everything […] when there is a difference of opinion, it’s slight and we quickly agree.[10]Peter James, quoted in Andrew L Urban, ‘Black Robe’, Cinema Papers, no. 82, March 1991, p. 10.

Actors Beresford has directed remark on the harmonious working atmosphere he is able to create on location. Bruce Greenwood said of his work with Beresford on Double Jeopardy (1999) that ‘Bruce creates an easy vibe on a set, the like of which I have never seen’;[11]Bruce Greenwood, quoted in Nui Te Koha, article on Double Jeopardy, Mercury, 25 October 1999. though Ashley Judd, on the same set, found Beresford’s predilection for Aussie idioms a little perplexing: ‘Is “not giving two hoots” a good or a bad thing?’ she pondered.[12]Ashley Judd, quoted in Te Koha, ibid. Paulina Porizkova, working on Her Alibi (1989), said: ‘He’ll do take after take and explain things instead of screaming.’[13]Paulina Porizkova, quoted in Domminey, op. cit.

The testimonies suggest a professionalism that stood Beresford in good stead on a film such as Black Robe, given the constraints under which he worked. The first included a budget of A$11 million and the need to avoid blowouts, though the budget was capacious enough to allow the occasional extravagance in the quest for authenticity, such as spending A$37,000 on cedar bark, transported from British Columbia, to create the Iroquois village to distinguish it from the elm-bark cladding of the Huron village.[14]Urban, op. cit., p. 11. The second was a rigorous working schedule, in a testing location in terms of its accessibility, ruggedness and changeable, volatile weather. The third was working with a cast of, if not exactly thousands, then many non–English speaking Native Americans as extras.

Planning, which, in Beresford’s case, involved both storyboarding and a punctilious preview of the day’s schedule before each shooting, was crucial. But Beresford also showed an ability to adapt, anticipate and improvise as circumstances required. The film required shooting in sequence to take into account the movement from autumn to early winter, and an eye for capitalising on the weather’s ‘moodiness’. James recounted:

One day we were in the middle of shooting a scene in brilliant sunshine. Suddenly the sky clouded over and we had a fierce rainstorm, followed by hail and snow and a spectacular rainbow – all in the space of 15 minutes! We didn’t think anybody’d believe it so we filmed the whole thing![15]Peter James, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, op. cit.

Working with local First Nations people as extras required a similar capacity to improvise. In the torture scene in which the captives, stripped naked, are forced to sing, the observing extras could not bring themselves to laugh mockingly, as required, seeing the actors treated so badly. Beresford then reshot the scene with the camera focused on the Indians while the now rugged-up actors broke into a rousing rendition of ‘Waltzing Matilda’, achieving the required laughter not only from the extras but from the crew as well.[16]Urban, op. cit., p. 12.

The co-production treaty

The co-production treaty between Australia and Canada, negotiated by the Australian Film Commission and Telefilm Canada on behalf of their governments, was ten years in the making, and provided the financial underpinning for films such as Black Robe that could compete with Hollywood, both in American markets and overseas.

The treaty also had creative and cultural implications. It can be best summed up as an industrial agreement that allowed for national, culturally significant stories to be told in commercially viable films made by international casts and crews without succumbing to ‘Hollywood values’. Black Robe was the first production under this agreement; in fact, the film was commissioned by a special memorandum of understanding before the treaty itself was signed. (The reason? The weather. To adapt that oft-quoted mantra from Game of Thrones, winter was coming, and a delayed filming schedule would have been impossible given the fierceness and bleakness of the Canadian winter.) The importance of the treaty was recognised at the Australian premiere of Black Robe, with Margaret Pomeranz hosting, and the federal arts minister and the Canadian high commissioner in attendance.

The financial components of the treaty provided for substantial government-assisted funding, from a variety of sources such as the 10BA incentive scheme and the Australian Film Finance Corporation, but with a requirement that 40 per cent be private investment. On Beresford’s recommendation, Lantos approached Milliken, who had worked with Beresford previously on The Fringe Dwellers, to undertake the task. After she had raised 26 per cent – more than half of the required contribution – her company then provided the remaining shortfall.

For Milliken, the project was a professed labour of love, both groundbreaking and challenging. She was attracted by its similarity to The Fringe Dwellers in its dealing with the impact of white man’s culture on indigenous people. She also welcomed the opportunities it provided for Australian filmmakers to work and develop their skills in collaborative international contexts; though she anticipated there would be creative tensions, given what she had noted about the different working styles of Australian film production units and others:

Australia has the best production system in the world […] There is a good chain of command, people help each other and there is a directness that avoids trouble. Elsewhere, each department has its own little area. They’re less interactive and so it runs less smoothly.[17]Sue Milliken, quoted in ibid., p. 10.

Milliken’s sense of a personal, not just professional, commitment to the project was shared by others. Lantos said the desire to avoid making a conventional Hollywood film meant it was worth waiting five years to raise the finance. Jake Eberts, CEO of British-based Allied Filmmakers, who had provided finance for films such as Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982), Chariots of Fire (Hugh Hudson, 1981) and Driving Miss Daisy, was thrilled that the shooting was taking place in a location where he had spent his childhood.

Bluteau’s portrayal is certainly not the Laforgue visualised by novelist Colm Tóibín in his reading of Moore’s novel, describing the character as ‘a towering and haunting presence in his mixture of will and weakness, faith and fear’.

The treaty’s ‘division of spoils’ awarded the pre-production to the Canadians. Its achievement in creating a sense of anticipation about the film was prodigious: a provocative and intriguing trailer featuring Indians so unlike the Hollywood stereotypes, even the benign version of them in Dances with Wolves (Kevin Costner, 1990); a narrative grounded in early Canadian history that was both a spiritual journey and a love story; the breathtaking landscape evoking the world of a pristine Saint Lawrence River. Alliance Communications ensured the film’s release in almost every possible outlet in Canada, as well as arranging reviews in all available media. Black Robe was also featured in several film and cultural festivals before its commercial release, a decision that not only enhanced its reputation as an art film that might be commercially viable, but also ensured the controversy around the authenticity of its portrayal of First Nations life remained a major public talking point.

The Australian contribution included most of the major creative team: not only Beresford and James, but also other Beresford ‘old hands’, including production designer Herbert Pinter, editor Tim Wellburn and sound recordist Gary Wilkins. Australia was also responsible for the post-production input, which included the sound editing (Penn Robinson and Jeanine Chialvo) and mixing (Phil Judd), while French composer Georges Delerue supervised the music score at the Australian Film Television and Radio School. Black Robe’s title sequence, the work of Australian designer Belinda Bennetts, revealed a remarkable inwardness with the film’s preoccupations. The camera pans over a contemporary map of the area, a map illustrated with demonic, snarling sea monsters and settlers and natives in conflict. The panning movement is interspersed with distinctive woodcuts of symbols of European culture and imperial power – the timepiece reminiscent of the ‘Captain Clock’ that so fascinates the First Nations characters in the opening sequence, the crown, the fort, the sailing ship – and a dangerous wilderness peopled by savage beasts and Indian warriors. The camera’s movement is accompanied by the soothing balm of liturgical music, which feels discordantly disconnected from the visuals. This is a strange, exotic, dangerous new world of cultures in conflict.

‘Determinedly unHollywood’

Critic Judy Stone describes Black Robe as ‘determinedly unHollywood’.[18]Judy Stone, ‘Black Robe Sheds Light on Indian Life’, San Francisco Chronicle, 3 November 1991. Speculating about what this might mean offers a way of appreciating the film’s distinctiveness. A Hollywood version might have featured a name star, highlighted and underscored the many dramatic moments in the script, and provided, if not exactly a happy ending, then at least one that would not have left Ebert so depressed.

Lantos has little doubt that had a Hollywood studio made Black Robe it would have insisted on an American box-office star. Beresford himself was not averse to casting a well-known actor in the role of Father Laforgue, despite his reservations about the star system, which he felt gave lead actors too much say in a film’s creation.[19]van den Nieuwenhof, op. cit., p. 10. Some investors were keen on De Niro or John Malkovich, but Beresford realised fees for such actors would prove prohibitive. For a time, Timothy Dalton was considered, but he cruelled his chances with investors by appearing in The King’s Whore (Axel Corti, 1990), an apparently execrable film in which he ends up suspended in a crucifix-like wheelchair![20]Coleman, op. cit., p. 145.

Bluteau was Beresford’s discovery. By happenstance, he had seen him in the role of a drug-addicted sex worker in a Canadian play, Being at Home with Claude, in London. Beresford thought Bluteau an actor who could convincingly portray faith, which he considered the hardest thing to represent on the screen.[21]Peter Malone, ‘Bruce Beresford’, Peter Malone author website, 15 May 1999, <http://petermalone.misacor.org.au/tiki-index.php?page=Bruce+Beresford&bl>, accessed 26 May 2020. Furthermore, surprisingly for the Canadian producers, Bluteau was fluent in English – an essential requirement, given that a decision had already been made, based on likely distribution markets, to have the French-speaking Jesuits and colonists speak English in contrast to the decision to have the First Nations characters speak in a variety of native tongues.[22]Urban, op. cit., p. 9. There are obviously limits to verisimilitude when it comes to commercial decisions.

Bluteau certainly showed intensity and commitment in the way he prepared for the role. Critic Andrew L Urban, when visiting the set, spoke of him as a ‘formidable actor’ and ‘the most dedicated actor [he had] ever seen on a set’:

Whether he is called or not, he is there, absorbing, watching – and discussing ideas with Beresford or James. He wants to know every frame, and has a possessive view of the film […] He has to know, and to agree with, all the major creative decisions.[23]ibid., p. 12.

Whether those qualities translated into a screen presence requiring similar attributes was a moot point among critics. Urban thought it did, pointing to a ‘spiritual credibility’ in Bluteau’s performance, evinced by ‘a certain inner stillness and a tremendous self-discipline’.[24]ibid. It was a quality lost on reviewer Sandra Hall: ‘With his martyr’s zeal, slight build, doggy brown eyes and terrier’s whiskers, Bluteau’s Laforgue may come across as authentically pious but he also has the look of a puppy waiting to be kicked.’ She added that the actor’s response to all of Laforgue’s trials and tribulations is ‘an all-purpose mournfulness’.[25]Sandra Hall, ‘High Morals, Low Drama’, The Bulletin, 3 March 1992, p. 106. The New York Times’ Vincent Canby felt something similar:

The characters, as written and performed, are perfunctory functions of the plot. Mr. Bluteau […] looks right as Father Laforgue, but the priest goes through the film simply responding to the world around him. He’s a passive and rather wimpish figure instead of a heroically troubled one.[26]Vincent Canby, ‘Saving the Huron Indians: A Disaster for Both Sides’, The New York Times, 3 October 1991, <https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/30/movies/review-film-saving-the-huron-indians-a-disaster-for-both-sides.html>, accessed 26 May 2020.

Bluteau’s portrayal is certainly not the Laforgue visualised by novelist Colm Tóibín in his reading of Moore’s novel, describing the character as ‘a towering and haunting presence in his mixture of will and weakness, faith and fear’ and a ‘doubtful and determined hero’.[27]Tóibín, op. cit.,p. xiii. Casting an actor such as Liam Neeson might have realised that visualisation (Oskar Schindler as Father Laforgue?), but it might also have skewed the film’s intention, which was to see in Laforgue’s personal narrative a larger tension between two conflicting cultures. An actor with the kind of resonance Neeson’s screen persona possesses might have made a more optimistic ending possible, one focused on the film’s penultimate moment, Laforgue’s final act of redemptive understanding – praying for the Hurons’ relief from physical suffering, not their salvation. In other words, an ending that focuses on a heroic, altruistic decision by the film’s protagonist, and an ending without the grim ‘epitaph’ that focuses on the wider devastating implications of the Jesuits’ presence in New France in the first place.

Many of the Canadian reviewers were overwhelmed by the ways in which the cinematography evoked the role the landscape – and the human interaction with it – had played in shaping the country’s history.

What critics such as Hall and Canby fail to recognise, however, is the ways in which Beresford makes Laforgue’s inner spiritual life a cinematic creation, and the ways in which Bluteau’s slightness and youthfulness, even his wimpishness, are integral to that creation. In the opening shot of the film, Laforgue’s image fills the screen; but as he walks away from the camera, he is revealed as a diminutive figure, incongruously at odds with this rudimentary European settlement and his fellow Europeans who precariously inhabit it. He impatiently paces through the settlement with his eye on the cabin where not only his journey is sanctioned but also his fate is predicted by the commandant and the Jesuit superior. Neither of them expect him to survive. His moralistic reproach of the experienced trappers and their dealings with the natives reveals his naivety, his gaucheness and a sort of arrogance in the sureness of his judgement.

At the conclusion of the film, the chief of the epidemic-stricken Huron tribe asks Laforgue, ‘Do you love us?’ Before he answers affirmatively, images of the First Nations people he has encountered on his journey flash before his eyes: not only the Algonquins who guide him, but also the Iroquois chief who orders his torture, and Mestigoit (Yvan Labelle), the annoying, though hardly menacing, dwarfish shaman who convinces the Algonquins that Laforgue is a demon. It’s as if the whole weight of the human experience of his trip informs his answer.

Between these two moments, we get a rich cinematic portrait of Laforgue’s interior life. In three sharply drawn vignettes, his genteel Europeanness and his youthful, naive idealism are established. He is intrigued rather than repelled by the mutilated priest and his tale of a service that will bring ‘civilisation’ to ‘barbarism’. The cultured musical-salon scene suggests he finds it easy to remain chaste when sexual desire is expressed or constrained through rituals of romantic courtship and arranged marriages; but it is much harder for him to deny his sexual arousal when confronted with the raw sensuality of Daniel and Annuka making love. The conversation with his mother as he prays at the statue of Saint Joan of Arc in Rouen suggests that the prospect of martyrdom, as much as that of missionary service, motivates him. Collectively, the vignettes reinforce a sense of what Fenek Solère refers to as Laforgue’s ‘flawed and meager personal resources […] as he undertakes his river journey, the classic water passage motif intended to depict the inner journey of self-discovery’.[28]Fenek Solère, ‘Irreconcilable Differences: The Two Versions of Black Robe’, Counter-Currents Publishing website, 15 August 2018, <https://www.counter-currents.com/2018/08/irreconcilable-differences-2/>, accessed 26 May 2020.

As well as such cinematic construction of character and motivation, Moore judiciously adapts selected conversations from his novel to show the conflicted nature of Laforgue’s faith. Significantly, they are conversations with two of the most morally honourable characters in the film, Daniel and Chomina, pitting Laforgue’s Christian faith against First Nations beliefs. As discussed above, Daniel’s growing love for Annuka educates him into a sympathetic understanding of how the Indians see and experience the natural world as also being a spirit world.

An even more powerful passage in the book is the one in which the dying Chomina scorns the ‘Normans’ for being so oblivious to the ‘Paradise’ that is present in the natural world:

Look around you. The sun, the forest, the animals. This is all we have. It is because you Normans are deaf and blind that you think this world is a world of darkness and the world of the dead is a world of light. We who can hear the forest and the river’s warnings, we who speak with the animals and the fish and respect their bones, we know that is not the truth. If you have come here to change us, you are stupid. We know the truth. The world is a cruel place but it is the sunlight. And I grieve now, for I am leaving it.[29]Moore, Black Robe,op. cit., p. 166.

In the face of such powerfully articulated beliefs, Laforgue’s faith seems jejune and clichéd … and wavering. Beresford puts it bluntly: ‘Chomina is a raving intellectual compared to the Jesuits who, basically, lived in cuckoo-land.’[30]Bruce Beresford, quoted in Elaine Dutka, ‘Do Indians Lose Again in Black Robe? They Assail New Film While Writer and Director Defend It’, Los Angeles Times, 11 November 1991, <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-11-11-ca-991-story.html>, accessed 26 May 2020. By the time Laforgue reaches the mission, he is well prepared to resist the sophism of the dying Father Jerome (played by a grizzled Frank Wilson, looking disconcertingly like his famous stage performance of Falstaff), who sees in the Hurons’ illness a chance to deceive them into baptism by offering it as a cure for their suffering. Laforgue may go through the motions of baptism, but there is no expression of joy from him at the Hurons’ salvation. His focus in his last prayer is on the alleviation of the Hurons’ physical suffering. ‘Spare them. Spare them, O Lord.’ In the novel, Moore describes the moment thus: ‘And a prayer came to him, a true prayer at last.’[31]Moore, op. cit., p. 249.

Several critics commented on the film’s narrative unfolding like a documentary: determined to stick to the facts as it unhurriedly moves to its conclusion without lingering over or highlighting any number of dramatic moments in the narrative. Beresford himself thought that his scrupulous attempt to ensure neither the Jesuits’ nor the Indians’ points of view were privileged in the telling contributed to this effect.[32]David Marshall & Rea Turner, ‘At Last, a Co-production We Can All Enjoy: Black Robe and Golden Fiddles’, Media International Australia, no. 66, November 1992, p. 96. The potentially dramatic moments suitable for the Hollywood treatment might have included Laforgue’s discovery of Annuka and Daniel making love; the decision of the Algonquins to abandon him and Chomina’s change of heart; any number of moments in the capture and torture scenes involving the Iroquois; or Laforgue’s discovery of the putrescent body of the murdered Father Duval at the mission: all ideal moments for a musical score to heighten the tension and underscore the drama … though that would have required a composer with a very different sensibility from Delerue’s.

Beresford has expressed irritation with scores that drown out natural sounds, while recognising that there is heavy pressure on directors to use Erich Korngoldian scores spelling out every emotion or thrill, or to let music intrude when there are none at all.[33]‘The Sound of Pictures: Bruce Beresford’, The Music Show with Andrew Ford, Radio National, 14 January 2020 <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/musicshow/the-sound-of-pictures-bruce-beresford/11682020>, accessed 26 May 2020. As such, Delerue was the ideal composer for the director. In Black Robe, there is no music to heighten tension or to underscore every emotion. Wherever appropriate, Delerue allows the landscape to ‘speak’ in its natural sounds, perhaps most powerfully in the scene in which Laforgue approaches the Huron village. The howling wind reinforces the physical bleakness of the landscape and the emotional bleakness of what he is about to discover, a community dying of influenza.

There is one exception, and it is a grand and appropriate one in both its splendour and its subtlety. That is the motif that accompanies the journey itself. The music soars as the canoes push off from the shore in the glorious autumnal weather. The camera opens out to include the presence of the sailing ship, no doubt recently arrived from the old world. It is as if we are invited to see this journey in canoes as the final stage of an epic physical journey between worlds, from the familiarity of the old into the strangeness of the new. As the journey becomes progressively more arduous and the party of travellers is reduced to three survivors in one canoe, the motif returns, only more subdued.

The theme works to underscore Beresford’s belief that what is to be celebrated is the physical journey itself, whatever its motives:

Even if you have no religious faith whatever or […] even if you despised the Jesuits, you would still find it an interesting story […] It is a wonderful adventure of the spirit and of the body. What those people did, going to a country where winters were far more severe than anything they had known in Europe, meeting people who were far more fierce than anyone they had ever encountered […] It’s the equivalent of today’s people getting into space shuttles and going off into space.[34]Beresford, quoted in Malone, op. cit.

Elsewhere, he described the Jesuits with Beresfordian bluntness: ‘They make [Arnold] Schwarzenegger look like a sissy.’[35]Bruce Beresford, quoted in Urban, op. cit., p. 9.

The ‘spirit’ in the landscape

Black Robe was both a critical and commercial success, especially in Canada, winning six Genies (the Canadian equivalent of the Oscars) in 1991. Both the cinematography and the production design were singled out for special praise.

Many of the Canadian reviewers were overwhelmed by the ways in which the cinematography evoked the role the landscape – and the human interaction with it – had played in shaping the country’s history. Writing for Montreal’s Gazette, critic John Stone called the film ‘a violent, unflinching, and brutally honest look at a pivotal period of Canadian history. It makes Dances with Wolves look like a Disney fantasy.’[36]Marshall & Turner, op. cit., pp. 95–6. There are images of Indians paddling canoes against the current for twelve hours a day, trudging through deep snow to hunt moose, dragging canoes along the banks of near-frozen rivers, huddling together for warmth in communal huts. There are moments of serenity in the landscape – especially at dusk as the Indians set up camp and Laforgue strolls the river bank, meditating – but the dominant image is that of humans pitted against nature. As Laforgue approaches the Huron village, the spiky palisades of its wall give the appearance of a giant hedgehog curled defensively: not just against human enemies, but against the fury of winter itself. A recurring long shot of an image of canoes as minuscule dots in a vast terrain reminds one of Thomas Hardy’s description in Tess of the d’Urbervilles of Tess and Marian picking swedes at that ‘grim starve-acre place’, Flintcomb-Ash, ‘crawling over the surface […] like flies’.[37]Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Broadview, Peterborough, ON, 1996 [1891], p. 312. This is a world that is at best indifferent, at worst hostile, to human endeavour. In the dying Chomina’s words: ‘The world is a cruel place …’

But it is also, for Chomina, ‘the sunlight’, and James evokes this as well. For the cinematographer, the landscape was more than a backdrop to the action; as Urban paraphrases him, ‘the trees and the rivers are as much characters as the people: they look brighter or bleaker, and they contribute to the mood’.[38]Urban, op. cit., p. 11. It is more, however, than mood. There is a sense in which the evocation of the landscape subliminally endorses the First Nations view of the natural world as both real and spiritual. The most startling example of this is when Laforgue becomes lost in the forest, and the trees momentarily take on the semblance of the pillars of the European cathedral where he encountered the mutilated priest. The forest, too, is a religious place, but Laforgue, as a ‘deaf and blind Norman’, cannot feel it. Instead, he feels fear, even terror, and then relief when he meets the Indians, who move relaxedly and assuredly through the forest while good-naturedly chiding Laforgue for his stupidity in feeling ‘lost’.

The illusion of ‘authenticity’

Similarly, praise was accorded to the production and costume design work of Pinter, Renée April and John Hay, and their teams, for the seemingly authentic look of the film. Their obsession with authenticity seemed contagious. One gets the impression that everyone involved with the film engaged in research of one kind or another to achieve that authenticity, beginning with Moore himself, who – along with his exhaustive reading of the Jesuits’ histories of the period – travelled to research centres in Canada where records of early Iroquois and Huron history and customs are kept, and to sites of early Iroquois and Huron settlements. To find actors and extras for the film, casting director Clare Walker and Beresford braved a swamp in northern Quebec in black-fly season to observe Cree people still living a traditional life style. James’ decision to film the seduction scene through the fire was based on a Jesuit’s remark about the Indians that he came across during his research: ‘They spend their lives in smoke – and eternity in flames.’[39]James, quoted in ibid., p. 10.

For Pinter, when working on a period so early in North American history, ‘the research (was) the most fascinating part’.[40]Herbert Pinter, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, op. cit. He loved the fact that the film was shot in mud and snow, replicating the fact that, for the Jesuits, the winter of 1634 was the bleakest they had ever encountered. The production team hired an army of tradespeople and specialist artisans, such as clockmakers and armourers, to create furniture, tools, canoes, weapons, whole villages in different kinds of bark – the lot. The costumes for a cast of 400 were made of furs rejected by the garment industry and ‘weathered’ with mud and latex. The jewellery and decorations were made from an assortment of chicken and fish bones, porcupine quills and feathers, but few beads, since beads were a recently introduced European trading commodity.

It was, of course, an illusion of ‘authenticity’. No actor (with the possible exception, perhaps, of Daniel Day-Lewis) wants to be the real thing in temperatures of −30 degrees Celsius for the sake of art. So performers were fitted with wetsuits under their costumes when paddling on the river, and woollen socks, plastic bags and felt boots under their moccasins, which meant ‘everyone ended up with size 11 feet’.[41]ibid.

‘They did it like dogs in the dirt’ … or did they?

A film’s claim to ‘authenticity’, however, can be a double-edged sword, as Ward Churchill, the film’s sternest critic, attests. Black Robe, he said, ‘is expressly intended to convey a bedrock impression that what is depicted is “the way it really was”’.[42]Ward Churchill, ‘And They Did It Like Dogs in the Dirt …: An Indigenist Analysis of Black Robe’, reprinted in Fantasies of the Master Race: Literature, Cinema, and the Colonization of American Indians, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1998, p. 226. As far as he was concerned, that was a myth – aided by film critics ‘who postured as if they were suddenly possessed of an all-encompassing and scholarly historical competence’[43]ibid., p. 228. – that needed challenging. He argued that the film’s look of authenticity blindsided them to deficiencies in its depiction of First Nations culture and beliefs.

Criticism of a like kind, however, was there well before the publication of Churchill’s provocative essay ‘And They Did it Like Dogs in the Dirt …: An Indigenist Analysis of Black Robe’ in 1992. Both Moore and Beresford realised that there were features of the novel that would prove controversial if they were included in the script. One was the passage in which the Iroquois not only kill Chomina’s young son but cook and eat him (as well as Laforgue’s finger, severed by a clam shell, for good measure). The other was the constant stream of Algonquin language and banter that was ‘ribald, acerbic, and scatological’.[44]Hall, op. cit., p. 106. There is no ‘Agnonha will cut our balls off’, or ‘as fast as wet shit through a bumhole’ or ‘What is that dog talk, you hairy pig?’ in the film. More’s the pity, Hall thought, given it reduced the irreverence of much of the Algonquins’ dealing with Laforgue and made the film err on the side of solemnity.[45]ibid. The decision to restrain such language, Moore suggests, was also a practical one. Subtitles full of such a rich mix of ribald and scatological idioms would have looked risible, and possibly distracted the audience’s attention from the visual narrative itself.

Such discreet self-censorship was evidently insufficient to quell criticism. Whenever Moore visited the set, many of the First Nations performers either snubbed him or argued with him about aspects of the ways in which their culture was portrayed.[46]Stone, op. cit. In one instance, they convinced Moore to change the details of the killing of Chomina’s son, arguing that no chief would do that. The compromise was to have the boy killed by one of the Iroquois war party.

The arguments continued with successive screenings and panel discussions as the film was released throughout North America. In Los Angeles, Bonnie Paradise of the American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts complained, ‘This movie shows savage hostility – not our culture.’[47]Bonnie Paradise, quoted in Dutka, op. cit. Three of the major First Nations actors involved in the film offered differing perspectives, however. Billy Two Rivers, who plays Ougbemat and also coached the cast in the Mohawk language, thought the film truer to historical fact than Dances with Wolves, though the latter portrayed native people more positively. He was sceptical, however, of the research on which the film was based. He believed the Jesuit letters in Relations distorted the facts, exaggerating the deprivation and brutalities the missionaries confronted, thereby making their service seem more heroic as a way of raising funds for their missionary work.[48]Stone, op. cit. Schellenberg agreed that there was an element of stereotyping in the portrayal of the Indians as ‘one-dimensional primitive characters seen through the eyes of white men’, but quipped, ‘If the movie offended you, don’t read the book.’[49]August Schellenberg, quoted in Dutka, op. cit. Tantoo Cardinal, who plays Chomina’s wife, welcomed the controversy as a catalyst for political action on indigenous rights: ‘All this rabble-rousing is actually exciting. Friction is necessary for change.’[50]Tantoo Cardinal, quoted in ibid. After seeing the film at its world premiere, she apologised to Moore: ‘I misjudged you. I didn’t realise the film was about spiritual matters. I liked it.’[51]Tantoo Cardinal, quoted in Stone, op. cit.

Moore himself expressed surprise at the reactions of First Nations critics:

Bruce’s intent […] and mine was to be deeply sympathetic to the Indians – people who believed in their world of nights and the power of dreams – and critical of the Jesuits who were arrogant and ruthless about baptizing them. If anyone should protest, it should be Jesuits […] but they haven’t said a word.[52]Brian Moore, quoted in Dutka, op. cit.

For his part, Churchill acknowledges Black Robe as a magnificent aesthetic and technical achievement. He praises Beresford’s artistic integrity in how he captures a ‘certain sense of his subject matter in ways which are not so much atmospheric as environmental in their nuance and intensity’.[53]Churchill, op. cit.,p. 225. He identifies the components that contributed to that artistic integrity: James’ ‘brilliant’ cinematography, Delerue’s ‘superbly understated’ score, Pinter’s production design and the interactions between the ensemble of experienced and novice actors that allowed the latter ‘to transcend themselves in the quality of their performances’.[54]ibid., p. 227. As well as the First Nations extras, the novice actors included the young romantic leads, high school student Holt and Young, a teenage Canadian-born Australian, a sort of hybrid symbol of the international interconnections of the production. And Churchill is particularly insightful about the ways in which Wellburn’s editing contributed to the film’s documentary-like narrative pace, describing the outcome as

a nearly perfect editing balance of pace and continuity, carrying the viewer along through the movie’s spare 100 minutes even while instilling the illusion that things are stretching out, incorporating a scope and dimension which, upon reflection, one finds to have been entirely absent.[55]ibid., p. 225.

The sticking point for Churchill, however, is the film’s depiction of First Nations culture as one given to voracious sexuality and promiscuity, irrational and primitive spirituality, and barbaric, ritualistic violence – with no corresponding counterpoint representing the brutality of the French colonising powers. Most controversially, he states that, for all Black Robe’s technical achievements, this unconscious bias makes it the kind of film that the Nazis might have made about their vanquished opponents had they won World War II.[56]ibid., p. 234. The end product, he argues, is one that puts an aesthetic gloss on what was basically an act of genocide, and that stifles genuine engagement with the real issues and consequences of indigenous–settler relations in Canada.

The sticking point for Churchill is the film’s depiction of First Nations culture as one given to voracious sexuality and promiscuity, irrational and primitive spirituality, and barbaric, ritualistic violence.

Predictably, Churchill’s essay provoked considerable debate in academia. Kristof Haavik, for example, takes on each aspect of Churchill’s criticisms of the film in a meticulously argued, forensic rebuttal.[57]Kristof Haavik, ‘In Defense of Black Robe: A Reply to Ward Churchill’, American Indian Culture and Research Journal,vol. 31, no. 4, 2007, pp. 97–120. He locates every example of First Nations life portrayed in the film in historical records and sources, as well as eliciting the ways in which they are given specific and nuanced dramatic life. For example, without dismissing the Algonquins’ casual promiscuity or downplaying Annuka’s forthright sexuality, he notes that the genuine love she and Daniel share is expressed with tenderness and intimacy. They do not consummate it ‘like dogs in the dirt’. Similarly, the Iroquois’ torture of the captives is portrayed as brutal and ritualistically cruel. For reviewer Peter Stack, ‘the violence stops just short of unbearable’,[58]Peter Stark, ‘A Dark, Gritty View of Frontier Clash’, San Francisco Chronicle, 8 November 1991. but in Haavik’s view the scene is not sensationalised, nor are the Iroquois demonised for their behaviour. When Daniel angrily exclaims that ‘the Iroquois are not men; they are animals’, Chomina chides him, ‘They are the same as us or Hurons.’

More importantly, Haavik explores the ways in which the film reveals its respect for First Nations culture and beliefs in cinematic terms. In the ceremony celebrating the impending journey, the European and native cultures are juxtaposed as ones sharing similar rituals. Both Champlain and Chomina as chieftains are seen preparing for the ceremony by donning their ‘armour’ and ceremonial robes; both settlers and Indians celebrate the occasion with music. The fact that Champlain’s robe is made of beaver skins leads one of the settlers to ask, acerbically, ‘Who is colonising who?’ It is a question that resonates throughout the film. The fact that the script focuses on Daniel’s transformation rather than the more lurid images of settlers ‘going native’ in the opening scenes of the novel, suggests the question might be rephrased as ‘Who is civilising who?’ Daniel’s boredom with life in the settlement and his shallow toying with the possibilities of becoming a priest back in France suggest an aimless, drifting life, whereas his love for Annuka and his acceptance of her culture give his life richness and purpose. Similarly, the way Chomina’s death is filmed portrays the She Manitou who comes to claim his spirit not as the hallucination of a dying man, but as a palpable presence, glimpsed in the landscape through the falling snow.

At the conclusion of his essay, Haavik assesses the film as being more than even-handed in its recognition of the respective claims of the settlers and the Indians to being ‘civilised’. Like Moore, he implies that it is the Jesuits who perhaps should have complained about their representation, not First Nations viewers. Black Robe’s trajectory, he argues, from ‘the very first shot […] of sea monsters on the map’ indicates ‘how little Europeans of the time understood about the broader world’. Thus, he argues, the film

presents the falsehood of European beliefs, the humanity of Indians, the inherent value of their civilization, and the catastrophic results of tampering with it, no matter how generous the intentions. A straight line of ignorance and condescension leads from the sea serpent of the first frame to the destruction of the Huron described in the last.[59]Haavik, op. cit., pp. 114–5.

‘No matter how generous the intentions.’ As with the Jesuits, so with postcolonial texts when it comes to representing the Other, perhaps even more so with a film adaptation of a novel than the novel itself. Elizabeth Flann saw this as a problem with Black Robe’s climactic moment in which the Hurons confront Laforgue with the question, ‘Do you love us?’ Laforgue is allowed his conflicted confusions, whereas the Hurons’ perspective is reduced to an almost caricature-like ‘childlike simplicity’.[60]Elizabeth Flann, ‘A Sea Change: Two Journeys from Home to the New World. A Postcolonial Examination of the Films The Piano and Black Robe’, Practice: A Journal of Visual, Performing and Media Arts, no. 1, Summer 1996/1997, pp. 3–11. The film elides the considerable space the novel gives to the ways in which First Nations people – be they Algonquin, Huron or Iroquois – discuss, debate, confer, decide or even vote on everything from how to interpret a particular dream to how to deal with the Jesuits (kill them? Ransom them?). There are certainly short scenes, ‘snapshots’, of the Indians parleying throughout the film that cumulatively suggest a mixture of rationality and sophism in their thinking, just as there is in European habits of thought, but they lack the nuanced dramatisation present in the novel.

A caveat: Saint Joan?

Finally, a caveat, and probably a pedantic one, about a film I consider a very impressive achievement. Given Black Robe’s rigorous approach to authenticity, I found it a little disconcerting that Laforgue is shown worshipping before a statue of Saint Joan in Rouen. It is true that Joan of Arc was burnt at the stake in Rouen some 200 years before the film’s action, and there may well have been a statue of her in Rouen as a place of pilgrimage. But Saint Joan? Joan was not canonised until 1920, though I grant that the locals may well have considered her not only a martyr but an unofficial ‘saint’, well before she was recognised as such by the Church.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Vincent Canby, ‘Saving the Huron Indians: A Disaster for Both Sides’, The New York Times, 3 October 1991, <https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/30/movies/review-film-saving-the-huron-indians-a-disaster-for-both-sides.html>.

Ward Churchill, ‘And They Did It Like Dogs in the Dirt …: An Indigenist Analysis of Black Robe’, Fantasies of the Master Race: Literature, Cinema, and the Colonization of American Indians, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1998, pp. 225–37.

Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Roberstson, Sydney, 1992, pp. 144–50.

Elaine Dutka, ‘Do Indians Lose Again in Black Robe? They Assail New Film While Writer and Director Defend It’, Los Angeles Times, 11 November 1991, <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-11-11-ca-991-story.html>.

Elizabeth Flann, ‘A Sea Change: Two Journeys from Home to the New World. A Postcolonial Examination of the Films The Piano and Black Robe’, Practice: A Journal of Visual, Performing and Media Arts, no. 1, Summer 1996/1997, pp. 3–11.

Kristof Haavik, ‘In Defense of Black Robe: A Reply to Ward Churchill’, American Indian Culture and Research Journal,vol. 31, no. 4, 2007, pp. 97–120.

Sandra Hall, ‘High Morals, Low Drama’, The Bulletin, 3 March 1992, p. 106.

Dougal Macdonald, ‘Masterly Tale of Invasion of Early Canada’, The Canberra Times, 29 February 1992.

Peter Malone, ‘Bruce Beresford’, Peter Malone author website, 15 May 1999, <http://petermalone.misacor.org.au/tiki-index.php?page=Bruce+Beresford&bl>.

David Marshall & Rea Turner, ‘At Last, a Co-production We Can All Enjoy: Black Robe and Golden Fiddles’, Media International Australia, no. 66, November 1992, pp.93–8.

Brian Moore, Black Robe, Head of Zeus, London, UK, 2017 [1983].

Fenek Solère, ‘Irreconcilable Differences: The Two Versions of Black Robe’, Counter-Currents Publishing website, 15 August 2018, <https://www.counter-currents.com/2018/08/irreconcilable-differences-2/>.

Peter Stack, ‘A Dark, Gritty View of Frontier Clash’, San Francisco Chronicle, 8 November 1991.

Judy Stone, ‘Black Robe Sheds Light on Indian Life’, San Francisco Chronicle, 3 November 1991.

Andrew L Urban, ‘Black Robe’, Cinema Papers, no. 82, March 1991, pp. 6–12.

Liz van den Nieuwenhof, ‘What’s Driving Mr Beresford’, Sunday Herald Sun Sunday Magazine, 9 January 2000, pp. 8–10.

MAIN CAST

Father Laforgue Lothaire Bluteau Daniel Aden Young Annuka Sandrine Holt Chomina August Schellenberg Chomina’s Wife Tantoo Cardinal Ougebmat Billy Two Rivers Neehatin Lawrence Bayne Awondoie Harrison Liu Oujita Wesley Côté Father Jerome Frank Wilson Champlain Jean Brousseau Mestigoit Yvan Labelle

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1991 Length 101 minutes Executive Producers Jake Eberts, Brian Moore & Denis Héroux Producers Robert Lantos, Sue Milliken & Stéphane Reichel Director Bruce Beresford Writer Brian Moore Director of Photography Peter James Editor Tim Wellburn Music Georges Delerue Production Designer Herbert Pinter Costume Designers Renée April & John Hay Art Director Gavin Mitchell Supervising Sound Editor Penn Robinson Dialogue Editor Jeanine Chialvo Casting Director Clare Walker

Endnotes

| 1 | Hilary Mantel, A Place of Greater Safety, Harper Perennial, London, UK, 2007 [1992], p. 398. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Brian Moore, ‘Author’s Note’, Black Robe, Head of Zeus, London, UK, 2017 [1983], p. xix. |

| 3 | Brian Moore, quoted in Colm Tóibín, ‘Introduction’, in ibid., p. xiii. |

| 4 | Roger Ebert, ‘Black Robe’, RogerEbert.com, 1 November 1991, <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/black-robe-1991>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 5 | Bruce Beresford, quoted in Liz van den Nieuwenhof, ‘What’s Driving Mr Beresford’, Sunday Herald Sun Sunday Magazine, 9 January 2000, p. 9. |

| 6 | Peter Coleman, Bruce Beresford: Instincts of the Heart, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1992, p. 144. |

| 7 | Bruce Beresford, quoted in Bruce Domminey, feature on Her Alibi, New Idea, 1 April 1989. |

| 8 | Beresford, quoted in van den Nieuwenhof, op. cit., p. 8. |

| 9 | Brian Moore, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, Black Robe press kit, 1991. |

| 10 | Peter James, quoted in Andrew L Urban, ‘Black Robe’, Cinema Papers, no. 82, March 1991, p. 10. |

| 11 | Bruce Greenwood, quoted in Nui Te Koha, article on Double Jeopardy, Mercury, 25 October 1999. |

| 12 | Ashley Judd, quoted in Te Koha, ibid. |

| 13 | Paulina Porizkova, quoted in Domminey, op. cit. |

| 14 | Urban, op. cit., p. 11. |

| 15 | Peter James, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, op. cit. |

| 16 | Urban, op. cit., p. 12. |

| 17 | Sue Milliken, quoted in ibid., p. 10. |

| 18 | Judy Stone, ‘Black Robe Sheds Light on Indian Life’, San Francisco Chronicle, 3 November 1991. |

| 19 | van den Nieuwenhof, op. cit., p. 10. |

| 20 | Coleman, op. cit., p. 145. |

| 21 | Peter Malone, ‘Bruce Beresford’, Peter Malone author website, 15 May 1999, <http://petermalone.misacor.org.au/tiki-index.php?page=Bruce+Beresford&bl>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 22 | Urban, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 23 | ibid., p. 12. |

| 24 | ibid. |

| 25 | Sandra Hall, ‘High Morals, Low Drama’, The Bulletin, 3 March 1992, p. 106. |

| 26 | Vincent Canby, ‘Saving the Huron Indians: A Disaster for Both Sides’, The New York Times, 3 October 1991, <https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/30/movies/review-film-saving-the-huron-indians-a-disaster-for-both-sides.html>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 27 | Tóibín, op. cit.,p. xiii. |

| 28 | Fenek Solère, ‘Irreconcilable Differences: The Two Versions of Black Robe’, Counter-Currents Publishing website, 15 August 2018, <https://www.counter-currents.com/2018/08/irreconcilable-differences-2/>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 29 | Moore, Black Robe,op. cit., p. 166. |

| 30 | Bruce Beresford, quoted in Elaine Dutka, ‘Do Indians Lose Again in Black Robe? They Assail New Film While Writer and Director Defend It’, Los Angeles Times, 11 November 1991, <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-11-11-ca-991-story.html>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 31 | Moore, op. cit., p. 249. |

| 32 | David Marshall & Rea Turner, ‘At Last, a Co-production We Can All Enjoy: Black Robe and Golden Fiddles’, Media International Australia, no. 66, November 1992, p. 96. |

| 33 | ‘The Sound of Pictures: Bruce Beresford’, The Music Show with Andrew Ford, Radio National, 14 January 2020 <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/musicshow/the-sound-of-pictures-bruce-beresford/11682020>, accessed 26 May 2020. |

| 34 | Beresford, quoted in Malone, op. cit. |

| 35 | Bruce Beresford, quoted in Urban, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 36 | Marshall & Turner, op. cit., pp. 95–6. |

| 37 | Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Broadview, Peterborough, ON, 1996 [1891], p. 312. |

| 38 | Urban, op. cit., p. 11. |

| 39 | James, quoted in ibid., p. 10. |

| 40 | Herbert Pinter, quoted in Hoyts Distribution, op. cit. |

| 41 | ibid. |

| 42 | Ward Churchill, ‘And They Did It Like Dogs in the Dirt …: An Indigenist Analysis of Black Robe’, reprinted in Fantasies of the Master Race: Literature, Cinema, and the Colonization of American Indians, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1998, p. 226. |

| 43 | ibid., p. 228. |

| 44 | Hall, op. cit., p. 106. |

| 45 | ibid. |

| 46 | Stone, op. cit. |

| 47 | Bonnie Paradise, quoted in Dutka, op. cit. |

| 48 | Stone, op. cit. |

| 49 | August Schellenberg, quoted in Dutka, op. cit. |

| 50 | Tantoo Cardinal, quoted in ibid. |

| 51 | Tantoo Cardinal, quoted in Stone, op. cit. |

| 52 | Brian Moore, quoted in Dutka, op. cit. |

| 53 | Churchill, op. cit.,p. 225. |

| 54 | ibid., p. 227. |

| 55 | ibid., p. 225. |

| 56 | ibid., p. 234. |

| 57 | Kristof Haavik, ‘In Defense of Black Robe: A Reply to Ward Churchill’, American Indian Culture and Research Journal,vol. 31, no. 4, 2007, pp. 97–120. |

| 58 | Peter Stark, ‘A Dark, Gritty View of Frontier Clash’, San Francisco Chronicle, 8 November 1991. |

| 59 | Haavik, op. cit., pp. 114–5. |

| 60 | Elizabeth Flann, ‘A Sea Change: Two Journeys from Home to the New World. A Postcolonial Examination of the Films The Piano and Black Robe’, Practice: A Journal of Visual, Performing and Media Arts, no. 1, Summer 1996/1997, pp. 3–11. |