This article contains examples of historical racist language and imagery that some readers may find distressing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are also warned that the article features images and names of deceased individuals.

In June 2020, Netflix removed four Australian comedy shows starring Chris Lilley from its platforms in Australia and New Zealand.[1]See Jake Kanter, ‘Netflix Removes Chris Lilley Shows, but BBC Stands by Comedian – Including N-word Blackface Sketch’, Deadline,10 June 2020, <https://deadline.com/2020/06/netflix-bbc-chris-lilley-smouse-1202955205/>, accessed 7 July 2020. While no official reason was given, it was commonly assumed that this action was prompted by Black Lives Matter protests in the United States and around the world – demonstrations that have primarily served to bring attention to disproportionate rates of police violence against unarmed black people,[2]See Leah Asmelash, ‘How Black Lives Matter Went from a Hashtag to a Global Rallying Cry’, CNN, 26 July 2020, <https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/26/us/black-lives-matter-explainer-trnd/index.html>, accessed 15 August 2020. but also since sparked discussions about broader issues surrounding racial inequality, including that of media representation. The streaming service’s move brought renewed attention to longstanding criticisms of the programs, which feature several characters portrayed by Lilley, a white actor, using dark make-up – the practice known as blackface.[3]See, for example, Tyler Jenke, ‘Chris Lilley Under Fire for Sharing Controversial Blackface Video on Social Media’, The Brag, 30 July 2017, <https://thebrag.com/chris-lilley-under-fire-for-sharing-blackface-video-on-social-media/>, accessed 15 August 2020. But far from being outliers, these series were merely the most recent in a long line of Australian TV shows and films that have made use of the technique for either comedic or dramatic reasons.

This article seeks to provide a brief overview of the history of blackface[4]For the purpose of this discussion, I am concentrating on blackface, rather than associated issues of historical whitewashing, colourism, yellowface and blackvoice; these will be touched on in passing, but are not the focus of the piece. on Australian television. It is hoped it will be of some use as an introductory primer for those unfamiliar with the topic, but it is not meant to be definitive – the issue is so complex that any such endeavour would require a book-length study. In addition, far too much critical discourse about blackface has already been dominated by white critics, policymakers and creatives; as a white writer, I suggest that this article be read in conjunction with existing work on the matter by writers of colour.[5]See, for example, Maxine Beneba Clarke, ‘White Australia Has a Blackface History’, Overland, no. 199, Winter 2010, available at <https://overland.org.au/previous-issues/issue-199/feature-maxine-clarke/>; Morgan Godfrey, ‘Jonah from Tonga: The Modern Minstrel Show?’, The Guardian, 23 April 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/23/jonah-from-tonga-the-modern-minstrel-show>; Liz McNiven, ‘A Short History of Indigenous Filmmaking’, australianscreen <https://aso.gov.au/titles/collections/indigenous-filmmaking/>, all accessed 24 August 2020; and Marcia Langton, ‘Well I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and About Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, North Sydney, NSW, 1993.

An Australian tradition of minstrelsy

When people in the English-speaking world think of blackface today, it is primarily associated with the bad old days of slavery and racial segregation in the United States. It was there that minstrel shows, in which white performers painted their faces black in order to embody exaggerated African-American stereotypes, proliferated – a phenomenon that later came to be seen as deeply symbolic of a culture in which black Americans were openly discriminated against and treated as inferior, and, in the words of US researcher John Strausbaugh, by the 1960s ‘had become one of the few very absolute taboos in American culture’.[6]John Strausbaugh, quoted in Sean Illing, ‘The Complicated, Always Racist History of Blackface’, Vox, 17 February 2019, <https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/2/11/18215370/blackface-virginia-ralph-northam-american-history>, accessed 20 August 2020.

In Australia, the cultural role of blackface has been different, but not in the way that is often presumed. Many Australians over fifty years of age will be able to recall The Black and White Minstrel Show, a prime-time variety TV program produced by the BBC that made copious usage of blackface in its songs and performances. It originally screened from 1958 to 1978, and reruns could be seen on air in this country as late as 1987.[7]See TV guide, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 January 1987, p. 34.

Less well remembered, however, is the fact that Australia had its own small-screen minstrel series. Hal Lashwood’s Alabama Jubilee was first broadcast out of Sydney on the ABC from March 1958 until July 1959, going into hiatus for around a year before briefly re-emerging as Hal Lashwood’s Minstrel Show. Each of these programs, which appear to have featured essentially the same content, were devised and presented by Lashwood, a white entertainer with extensive experience in vaudeville, radio and theatre.[8]See Joyce Morgan, ‘Lashwood, Harold Francis (Hal) (1915–1992)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2016, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lashwood-harold-francis-hal-17116/>, accessed 24 August 2020. Episodes typically consisted of Lashwood appearing as the compere, Mr Interlocutor, who would interact with his sidekicks Mr Bones (Syd Heylen) and Mr Tambo (usually played by Jimmy Hanlon). Other regulars included Miss Carolina (Peggy Mortimer), Mr Melody (Neil Williams) and Mr Dixie (Jack Kersh). These were stock characters from minstrel stage shows: the cast wore minstrel dress and black make-up, the latter of which reportedly took fifteen minutes to apply and half-an-hour to remove. Episodes ran for thirty minutes and featured songs, dances and comedy, along with performances from guest stars (including some black performers, such as Indigenous singer Heather Pitt).[9]See ‘Ladies and Gentlemen … Be Seated’, ABC Weekly, vol. 20, no. 26, 25 June 1958, p. 9, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1436714371>, accessed 24 August 2020. Lashwood described the Alabama Jubilee as follows:

This show has tremendous appeal so far as children are concerned. For that reason I make sure that nothing to which exception could be taken goes into the material. I know that this is not sophisticated, subtle stuff – but then it’s not meant to be.[10]Hal Lashwood, quoted in ‘Simple Appeal of Show’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1958, p. 9.

The best-remembered instalment of Hal Lashwood’s Minstrel Show was an episode that aired in December 1960 featuring a guest appearance from African-American performer Paul Robeson, who was famed for his civil-rights activism as well as his cultural accomplishments as an actor and singer.[11]In the episode, Robeson sang several songs to a multiracial group of children. See ‘Television Topics’, The Biz, 21 December 1960, p. 8, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article190740891>, accessed 24 August 2020.

Reception to Lashwood’s minstrel programs appears to have been generally positive; The Sydney Morning Herald, for instance, declared it ‘refreshing to find a show with a direct, simple appeal’.[12]‘Simple Appeal of Show’, op. cit. There was some criticism, however – Max Harris, writing in The Bulletin, called the Alabama Jubilee ‘dismal’ (albeit apparently more for its production values than its insensitivities);[13]See Max Harris, ‘A New Cultural Deal?’, The Bulletin, 28 October 1961, p. 32, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-679975519/view?partId=nla.obj-680027263#page/n31/mode/1up>, accessed 15 August 2020. and Sydney’s Tribune, the organ of the Communist Party of Australia, ran a letter to the editor decrying the disrespectfulness of an ABC television announcer’s use of the N-word when promoting the show on air, though the writer did not cast aspersions on the program itself.[14]‘Negroes Defamed’, Tribune, 15 April 1959, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article236739624>, accessed 24 August 2020.

The existence of a homegrown minstrel show on prime-time Australian television may seem odd today, but was not so in 1959. Originally imported from the United States and Britain in the 1830s, minstrelsy soon found an enthusiastic reception in Australia, particularly in the second half of the nineteenth century, when it was arguably the most popular form of entertainment in the country.[15]See ‘The Evolution of Vaudeville’, The Age, 31 May 1941, p. 11, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/205149923>; and Gary Le Gallant, ‘Minstrelsy in Australia: A Brief Overview’, Warren Fahey’s Australian Folklore Unit, 14 May 1986, <https://www.warrenfahey.com.au/enter-the-collection/the-collection-m-z/minstrelsy/>, both accessed 24 August 2020. Australia produced several noted minstrel artists, including Harry Cash, Maud Fanning and Tom Coogan; legendary figures of Australian theatre, such as Roy ‘Mo’ Rene and George Brown Sorlie, were minstrels early in their careers; and one-time prime minister Arthur Fadden belonged to an amateur minstrel troupe in his early days.[16]See Margaret Bridson Cribb, ‘Fadden, Sir Arthur William (1894–1973)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1996, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fadden-sir-arthur-william-10141>, accessed 24 August 2020. Minstrel shows mainly satirised black Americans, but occasionally blackface was used to depict Aboriginal people – particularly in amateur theatricals during the early twentieth century – and local minstrels sometimes incorporated an Aboriginal-themed musical number into their act for variety.[17]See ‘Entertainments’, The Daily Herald, 12 November 1917, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article105440192>, accessed 17 July 2020. Meanwhile, visiting African-American performers were for a time denied entry to the country and subjected to considerable public hostility.[18]See ‘Australia Bars Negroes’, Variety, 2 May 1928, p. 1.

For over a hundred years, minstrelsy was the leading way many Australian audiences were exposed to black culture: through buffoonish caricatures that ridiculed and dehumanised groups of people.

The popularity of minstrelsy in Australia faded over the course of the twentieth century, due as much to changing tastes and competition from other modes of entertainment as to increases in racial sensitivity.[19]See Josephine O’Neill & Barrett Fleming, ‘A King Honoured Him’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1957, p. 9. However, the decline was a slow one, and minstrelsy not only continued to be performed on local stages until the 1980s,[20]The most common defence was exemplified in 1987 by Ken Jeacle, promoter for a stage version of The Black and White Minstrel Show, who told The Canberra Times:‘This show is purely and simply a character musical variety show. The black makeup is purely and simply a character makeup. And it’s not even black, it’s brown.’ Jeacle, quoted in Karen Middleton, ‘Black and White Minstrel Show’, The Canberra Times, 17 September 1987, The Good Times lift-out p. 11, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122122468>, accessed 24 August 2020. but also proved adaptable to other formats. For instance, from the 1930s to the 1960s, Australian audiences could listen to local radio programs such as C. & G. Minstrels and Minstrel Memories, the latter a 1964 production hosted by Lashwood.[21]See Richard Waterhouse, From Minstrel Show to Vaudeville: The Australian Popular Stage, 1788–1914, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW, 1990.

Lashwood was a passionate lobbyist for local content on Australian screens; he once said that the popularity of Alabama Jubilee served as ‘one more vindication of [his] belief that, given the facilities, the Australian artist is as good as any in the world’.[22]Lashwood, quoted in ‘Simple Appeal of Show’, op. cit. And his troupe was not the only domestic minstrel act to appear on television – comedy duo Skit and Skat, played by Al Kenny and Maurie Fields in blackface, guest-starred on Say It with Music in 1957 as well as the variety program Sydney Tonight in 1958. But Lashwood’s group would be the only one to have its own show, and that ended in 1961. This appears to have been due to a combination of cultural cringe and the economics of television production rather than any cultural opposition to the concept – as with many areas of Australian show business both in the 1960s and today, the minstrel market was dominated by an overseas behemoth (in this case, The Black and White Minstrel Show), and it was hard for local acts to compete. Regardless, memory of the existence of Australian minstrel artists faded over time, and the practice came to be seen as an American problem that had little relevance to Australian culture or history.[23]See David T Smith, ‘Why Isn’t Blackface Taboo for Australians?’, The New York Times, 4 November 2016 <https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/08/opinion/why-isnt-blackface-taboo-for-australians.html>, accessed 17 August 2020. But, for over a hundred years, minstrelsy was how numerous Australian performers made their living, and the leading way many Australian audiences were exposed to black culture: through buffoonish caricatures that ridiculed and dehumanised groups of people who historically had been and continued to be disenfranchised in white-majority societies.Even today, Lashwood’s minstrel shows remain among the very few prime-time Australian television programs in which the majority of regular characters have been black.

A dramatic monopoly

Blackface in drama served a different purpose to that in minstrelsy. The latter used make-up as a deliberately exaggerated effect for comic purposes, and there was minimal attempt at pretending the actors really were black. In contrast, blackface in dramatic depictions generally aimed at realism: the intent was to create suspension of disbelief in the eyes of the audience so that they could feel that they were observing a genuinely black character.

Prior to World War II, non-white characters in Australian dramatic stage shows and films were overwhelmingly played by white actors.[24]See Bruce Lawrence Dennett, ‘The Genesis of Indigenous Australian Characterisations in Feature Films’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, May 2012, available at <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b9b5/44fe0d25f59482044b1be32f7362bd042903.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. The first substantial play on an Australian subject written, published and performed in the country, Henry Melville’s 1834 production The Bushrangers; or, Norwood Vale, featured an Aboriginal character depicted by a white performer in blackface.[25]See Richard Fotheringham (ed.), Australian Plays for the Colonial Stage: 1834–1899, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld, 2006, p. 18, fn. 4. The same was the case for the first Aboriginal character to play a large role in a film, in Robbery Under Arms (Charles MacMahon, 1907).[26]Aboriginal trackers appear in the first feature made in Australia, The Story of the Kelly Gang (Charles Tait, 1906), but it is difficult to tell whether they are played by white performers in blackface or Aboriginal actors. See Ina Bertrand & William D Routt, ‘The Picture that Will Live Forever’: The Story of the Kelly Gang, The Moving Image series, no. 8, ATOM, St Kilda, Vic., 2007. The exclusion of Indigenous performers from most areas of the stage and screen industries mirrored the larger racial segregation that was the norm in Australia in the first half of the twentieth century – another uncomfortable aspect of Australian history that has sometimes been glossed over.[27]See Anna Kelsey-Sugg & Annabelle Quince, ‘Watershed Moments in Indigenous Australia’s Struggle to Be Heard’, ABC Radio National, 4 July 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-04/complex-history-of-indigenous-and-non-indigenous-australia/9930944>, accessed 20 August 2020.

Nonetheless, it was harder for cinema-goers than it was for theatre audiences to suspend disbelief watching a ‘blacked-up’ actor; the use of close-ups and camera lights, in particular, exposed the crudity of the technique to a greater degree. Accordingly, actors of colour, while still a minority, appeared with more regularity in film than on stage. The now-lost A Bushranger’s Ransom, or a Ride for a Life (EJ Cole, 1911) advertised itself as featuring ‘the first Australian aboriginal [sic] actor to appear in a photo. play’, the legendary stockrider Mulga Fred.[28]See ‘Entertainments’, The Brisbane Courier,3 April 1911, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19699763>, accessed 24 August 2020. Aboriginal performers were also cast in Moora Neya, or the Message of the Spear (Alfred Rolfe, 1911), Robbery Under Arms (Kenneth Brampton, 1920), The Dingo (Brampton, 1923), The Tenth Straw (Robert McAnderson, 1926), The Kid Stakes (Tal Ordell, 1927), The Romance of Runnibede (Scott R Dunlap, 1928) and Uncivilised (Charles Chauvel, 1936); Aboriginal boxer Sandy McVea had a key support role in The Enemy Within (Roland Stavely, 1918), as did Torres Strait Islander Utan – appearing alongside fifty-five ‘mostly Torres Strait’ extras – in Typhoon Treasure (Noel Monkman, 1938).[29]See, ‘On Location in the Coral Sea: Filming Typhoon Treasure’, The Telegraph (Brisbane), 18 December 1937, p. 18, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article184100208>, accessed 24 August 2020. Nonetheless, these were exceptions, and the Indigenous actors who did appear often did so alongside white cast members in blackface.[30]See Dennett, op. cit.; and Benjamin Miller, ‘The Mirror of Whiteness: Blackface in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, Spectres, Screens, Shadows, Mirrors: Special Issue, 2007 <https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/10252>, accessed 24 August 2020.

After World War II, blackface became less frequent, and a number of Aboriginal actors emerged on Australian screens, such as Henry Murdoch, Neza Saunders, Clyde Combo and Johnny Cadell; Robert Tudawali and Rosalie Kunoth-Monks played the lead roles in the feature film Jedda (Chauvel, 1955).[31]Despite this progress, Aboriginal performers were still subjected to discriminatory treatment. In 1951, an Actors’ Equity campaign – led by none other than Lashwood – protested against Indigenous extras being paid less than whites on the feature film Kangaroo (Lewis Milestone, 1952). See ‘Aboriginal Actors’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1951, p. 5. In addition, Aboriginal performers sometimes had to get government permission to accept work; see, for example, Peter Forrest, ‘Tudawali, Robert (1929–1967)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2002 <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/tudawali-robert-11889>, accessed 28 August 2020. However, just because blackface was less common did not mean that it had stopped. The second male lead in Jedda, the stockman Joe, was played by a white actor in dark make-up (Paul Reynall), while the second female lead in the film Captain Thunderbolt (Cecil Holmes, 1955), the Aboriginal woman Maggie, was played by Loretta Boutmy in what appears to be blackface.[32]Maggie was based on the real-life Aboriginal bushranger Mary Ann Bugg, who routinely inspired characters in films played by white actors in blackface – for instance, Ruby Butler’s performance as ‘Sunday’ in Thunderbolt (Jack Gavin, 1910), possibly the first depiction of a real-life Aboriginal person in a film. Both characters were described as ‘half-caste’, a technique often used to make the casting of white actors in black roles more palatable to audiences.

This duality of casting approaches for characters of colour – a combination of blackface and Aboriginal or other non-white actors[33]Not all black actors in early Australian television were Aboriginal. Harry Willis, an Australian of Jamaican descent, was cast as a Maori chief in an episode of ATN-7’s 1962 historical serial Jonah, and African-American dancer Joe Jenkins played lead roles in a number of TV dramas for the ABC, including a 1960 adaptation of The Emperor Jones. Jenkins was also a regular on the prime-time 1961 ABC variety show Just Barbara, which starred African-American singer Barbara Virgil, and Willis hosted the 1958 ABC variety show Aloha Hawaii – indicating that Australian television networks may have been more willing to showcase black talent if it was non-Aboriginal. – bled into early Australian television drama. The first recurring series made in Australia to regularly feature black characters was Whiplash, a western about a stagecoach line in nineteenth-century Australia that screened from 1960 to 1961. Aboriginal characters in the series were mostly played by Indigenous actors (such as Tudawali, Cadell and Murdoch), but the episode ‘The Legacy’ used a white actor in blackface (Reg Livermore), while ‘Dutchman’s Reef’ and ‘The Bone That Whispered’ told stories of whites who went to live among Aboriginal peoples, covering themselves in full-body black make-up. Likewise, the 1960 live TV play Dark Under the Sun concerned the relationship between a white woman and a ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal man; the latter was played by white actor Edward Brayshaw in dark make-up.

The visibility of Aboriginal actors on television screens shot up sharply in the second half of the 1960s and the early 1970s. In particular, the years 1965 to 1973 saw a number of key moments in modern-day Indigenous history, including the Wave Hill walk-off, the 1967 Referendum, the New South Wales Freedom Ride, the appointment of Neville Bonner to the Senate, the knighting of Douglas Nicholls, the international sporting achievements of Lionel Rose and Evonne Goolagong, the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra and the end of the White Australia policy. During this time, Aboriginal actors began guest-starring in increasing numbers on Australian drama series such as Homicide, Skippy the Bush Kangaroo and Riptide; Bob Maza and Bindi Williams had recurring roles on Bellbird and Woobinda (Animal Doctor), respectively; and Athol Compton had a starring part in the Hollywood-financed film The Games (Michael Winner, 1970).

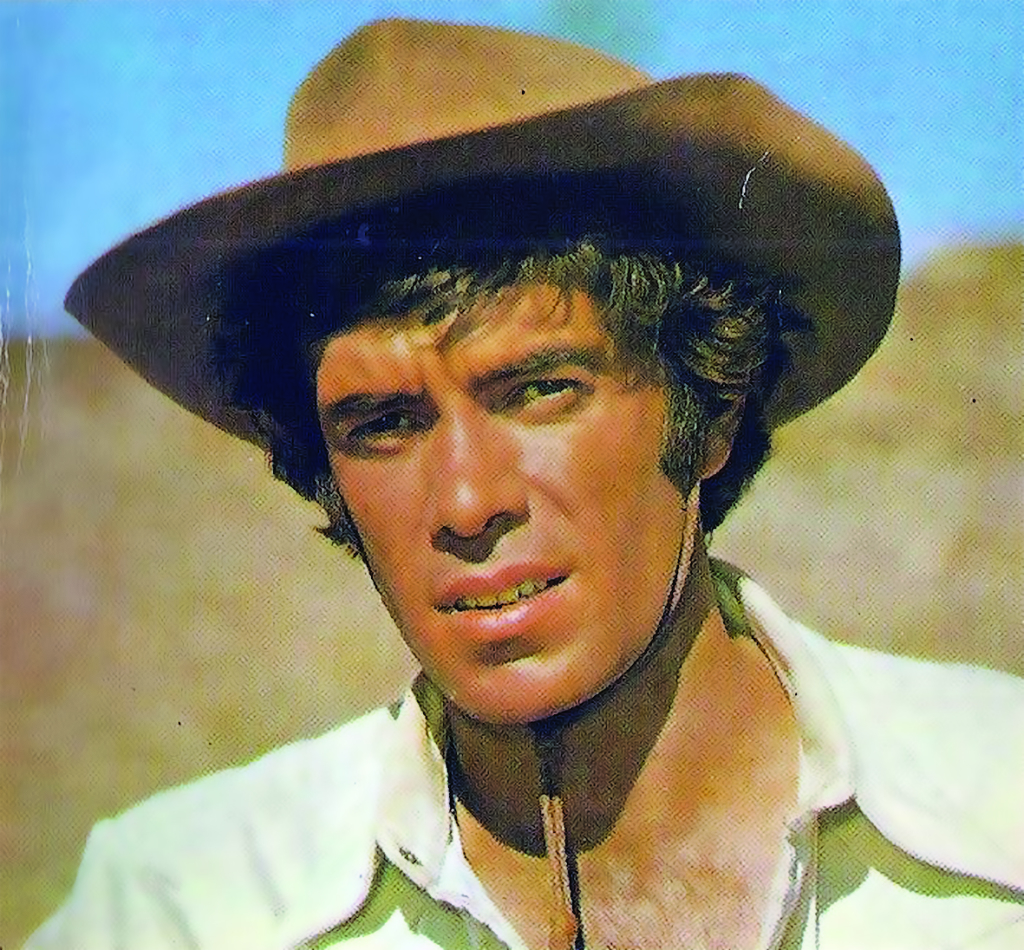

Despite this, blackface continued to be used on Australian television, particularly for leading roles. The 1966 ABC children’s adventure series Wandjina! featured a regular Aboriginal character, Linda, played by Julianna Allan in blackface, while the 1968 ATN-7 limited series The Battlers starred white actor Vincent Gil as an Indigenous boxer whose story was loosely based on the life of Rose. White Harold Hopkins was cast as a Melanesian in the 1969 ABC TV adaptation of Pastures of the Blue Crane, though he played the role without make-up.[34]See Alan Attwood, ‘The Case of Bony Is Not All Black and White’, The Sunday Age, 30 June 1991, p. 9. As producer Sue Milliken, who worked on the show, wrote in her memoir, ‘Casting white actors to play Aborigines in lead roles was the way it was done then.’[35]See Sue Milliken, Selective Memory: A Life in Film, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, Vic., 2018. The feature film Journey out of Darkness (James Trainor, 1967) starred white Ed Devereaux in blackface and a ‘flattened’ nose as an Aboriginal tracker – in pursuit of another Indigenous character, played by Sri Lankan singer Kamahl, whose love interest was played by Arrernte actor Julie Williams.[36]See ‘Native Girl Topless in Film Scene’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 1967, p. 32. ‘If the producers had had the time, they undoubtedly would have cast about for an Aboriginal actor,’ said Devereaux at the time. ‘But they had to have a man with experience.’[37]Ed Deveraux, quoted in Josephine O’Neill, ‘How an Actor Went Native …’, The Sun–Herald,3 December 1967, p. 106. The casting of Devereaux and Kamahl has been called ‘probably the worst case of miscasting in the history of Australian film’.[38]Ben Holgate, ‘Take Two on Black Cinema’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 October 1995, p. 17.

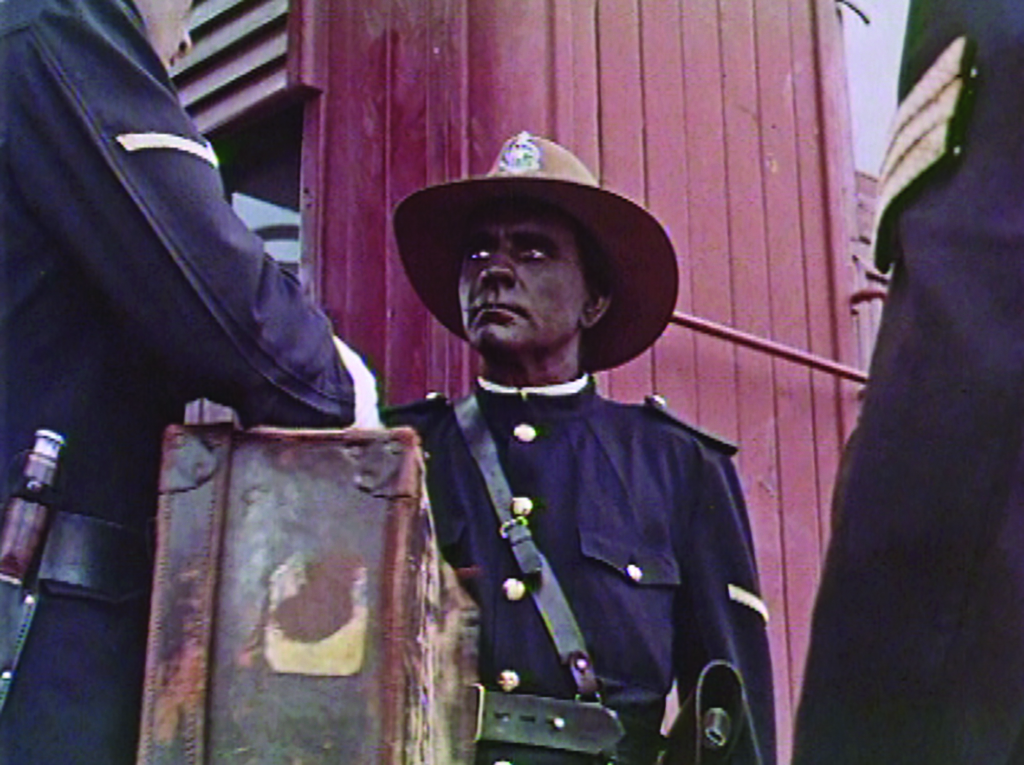

Blackface in Australian television drama reached an apogee with the 1972–1973 detective series Boney, based on Arthur Upfield’s acclaimed series of novels about detective Napoleon ‘Bony’ Bonaparte, son of a white father and Aboriginal mother. It was the first time an Indigenous character had been the protagonist of a recurring drama series; he was played by white New Zealander James Laurenson in dark make-up.

This decision received more criticism than any prior blackface casting in the history of Australian entertainment.[39]See, for example, Don Storey, ‘Boney’, Classic Australian Television, 2013, , accessed 20 August 2020. In a 1972 interview in The Sydney Morning Herald, Laurenson claimed that the show’s production company had ‘searched long and hard for an Aboriginal Boney’ without success; but Maza – who is extensively quoted in the same article – contended, ‘I could have guaranteed [producer] John McCallum ten articulate, sophisticated black people to play that part. He didn’t look very hard. Did he look at all?’[40]Bob Maza, quoted in Lenore Nicklin, ‘Black Is White and White Is Black’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1972, p. 7. The series did employ some Aboriginal actors – such as David Gulpilil, in his first screen role following Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971) – but occasionally resorted to blackface among its guest cast as well.

Boney proved a turning point in the use of blackface on Australian television drama; it is hard to find examples of it being used afterwards. Not only were audiences becoming increasingly sensitive to cultural and racial considerations, but they were no longer willing to accept that level of inauthenticity. There were still, however, numerous examples of non-Aboriginal actors, particularly whites, being cast as Aboriginal characters without make-up. Notably, white actor Cameron Daddo played Inspector Bonaparte, described now as ‘one-eighth Aboriginal’, in Bony, a 1991 TV-movie adaptation of the Upfield novels. When it was decided to turn Bony into a recurring series, Aboriginal groups protested over Daddo’s casting; after four months of negotiation, an agreement was reached with the Grundy Organisation that, among other things, Bony’s backstory would be adjusted so he no longer had any black ethnicity (but had instead been raised by Aboriginals), Aboriginal actors would be cast in non-stereotypical roles, a script consultative committee would advise on cultural issues, and the show would not engage in ‘blacking-up’ of performers.[41]Danielle Talbot, ‘TV’s New Deal: White Is White and Black Is Black’, The Age, 26 June 1991, p. 1. In hindsight, this was a progressive agreement suggesting reforms that would later be standardised,[42]See Terri Janke, Pathways & Protocols: A Filmmaker’s Guide to Working with Indigenous People, Culture and Concepts, Screen Australia, Sydney, NSW, 2009. but whose potential was not immediately realised by an industry that more likely saw it as a burden than an opportunity. If nothing else, however, it did formalise the death of blackface in Australian television drama.

Mockery and mockumentary

In comedy, however, blackface continued to thrive until recent years. From the 1970s to the 2000s, white comic Louis Beers performed regularly on stage in blackface and on radio as the Aboriginal character King Billy Cokebottle, a figure very much in the minstrel tradition.[43]See John van Tiggelen, ‘Call This Funny?’, Good Weekend, 6 October 2001, pp. 31–4. Beers was given his own television special in character on Sky in 1994,[44]See TV guide, Now, 2–8 October 1994, p. 62. but his act’s on-screen appearances were few. It has been been rare for white performers on Australian television to use blackface to deliberately satirise Aboriginal people, but there have been exceptions, such as Sam Newman’s appearance in blackface on The Footy Show (AFL)in 1999 mocking Noongar footballer Nicky Winmar.[45]See Karen Lyon, ‘Footy Show’s Black-face Gag Sparks Storm of Protest over Racism’, The Age, 26 March 1999, p. 3. Generally, however, the practice has been taboo on screen (if less so on stage) – Newman’s segment was highly controversial, as was Beers’ entire career.[46]See Karen Austin, ‘Aboriginal Humour: An Investigation into the Nature and Purposes of Indigenous Australian Performance Humour and Its Contributions to Australian Culture’, PhDthesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, August 2017, available at <https://flex.flinders.edu.au/file/663b8af3-5a52-465f-851109faea5ec821/1/08082017%20THESIS%20AUSTIN%202017%283%29.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020.

There has been no such reticence towards lampooning other racial groups. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the sketch shows The D Generation, Fast Forward and The Late Show had several episodes featuring performers in blackface, brownface and yellowface;[47]See Sam Duncan, ‘When Comedy Was Anything but Politically Correct: As Comedians Mourn the Death of Australian Jokes, We Take a Look Back at Old Sketches That Would Cause Outrage Today’, Daily Mail Australia, 2 May 2018 <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5680605/The-old-Australian-comedy-sketches-NEVER-away-today-political-correctness.html>, accessed 24 August 2020. In the mid 1990s, Greg Ritchie’s brownface character Mahatma Cote was a regular feature on Channel Nine’s cricket coverage and The Footy Show (NRL);[48]See Matt Condon, ‘Sultana of Sport’, Now, 2–8 July 1995, pp. 8–9. and the ABC’s Monte Dwyer once presented the weather in dark make-up imitating singer Bobby McFerrin.[49]See ‘Monte Dwyer Sizzle’, YouTube, 4 December 2011, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cE930rIs36E>, accessed 24 August 2020. In 2007, The Chaser Decides featured a Jackson 5–style performance in blackface, a skit that presenter Chas Licciardello much later conceded was ‘wrong’ and ‘almost identical’[50]Chas Licciardello, in ‘Is Blackface on Australian TV Really That Bad?’, YouTube, 30 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qylLWyjxZrs>, accessed 24 August 2020. to the notorious ‘Jackson Jive’ blackface dance number on Hey Hey It’s Saturday in 2009. That latter performance led to an on-air apology from host Daryl Somers – not so much for the act as for offending guest Harry Connick Jr – but was nonetheless defended by many media commentators at the time.[51]See Meg Watson, ‘Here’s What Happened When Australia Defended Blackface in 2009’, Junkee, 23 February 2016, <https://junkee.com/heres-happened-australia-defended-blackface-2009/73879>; Meg Watson, ‘Here Are All the High-profile Australians Who’ve Defended Blackface Lately’, Junkee, 22 February 2016, <https://junkee.com/here-are-all-the-high-profile-australians-who-defended-blackface-today/73840>; and ‘Hey Hey It’s Time to Talk About Blackface!’, It’s Not a Race, Radio National, 31 May 2017, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/itsnotarace/hey-hey-its-time-to-talk

-about-blackface/8568856>, all accessed 24 August 2020.

While this relatively recent enthusiasm for using blackface for comic purposes was not a uniquely Australian phenomenon – many comedy series in the UK and US alike, including 30 Rock, Little Britain, Peep Show, Community and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, have made use of it in the twenty-first century, albeit more often than not making blackface’s taboo status the subject of the joke and presenting the practice as unambiguously racist[52]Many episodes from these shows have since been withdrawn from streaming services. See Christi Carras, ‘These TV Shows Recently Removed Blackface Episodes. Here’s What You Need to Know’, Los Angeles Times, 30 June 2020, <https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-06-30/blackface-episodes-pulled-the-office-golden-girls-30-rock?>, accessed 24 August 2020. – one of its most notable exponents has been writer-performer-director Chris Lilley, who in several shows over the past decade-and-a-half has used the device for the characters Jonah Takalua in Summer Heights High and Jonah from Tonga, S.mouse in Angry Boys, and Jana Melhoopen-Jonks in Lunatics (he also used yellowface to portray Ricky Wong in We Can Be Heroes – who in turn performs a stage show in blackface – and Jen Okazaki in Angry Boys). ‘I don’t think there should be any rules,’ Lilley offered, when asked about his use of make-up in 2013. ‘Things seem to be a little more relaxed in Australia with that kind of thing. But I think it’s all about the context.’[53]Chris Lilley, quoted in Eric Spitznagel, ‘Q&A: Chris Lilley on Drag, Blackface, Teenage Girls & Confrontational Comedy’, Esquire, 14 November 2013, <https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/interviews/a25930/chris-lilley-interview/>, accessed 24 August 2020.

Lilley’s work is unusual in that it it is comedy that combines elements of Australia’s two earlier blackface traditions: minstrelsy and drama. The majority of Australian blackface on television that has been played for laughs has previously been presented in a sketch- or variety-show format, but Lilley works in the genre of mockumentary, which aims for a sense of reality, albeit in a comic way; in his words, ‘I wanted people to tune in and think that they might be watching a real documentary. I wanted them to think, “This seems real.”’[54]ibid. Unlike, say, Mahatma Cote, his characters are not experienced in brief snippets, but in long-running serial story arcs over multiple episodes. Lilley’s work has been much acclaimed and much criticised; the criticism, seemingly once marginalised, has increased in size and scope in recent years.[55]See, for example, Seini F Taumoepeau, ‘Chris Lilley’s Jonah Is Not from Tonga, I Am. It’s Time to Dismantle Racist Brownface Stereotypes’, The Guardian, 12 June 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/12/chris-lilleys-jonah-is-not-from-tonga-i-am-its-time-to-dismantle-racist-brownface-stereotypes>; Dory Jackson, ‘Chris Lilley Accused of Blackface in Lunatics: Examining the Comedian’s Other Controversial Characters’, Newsweek,11 April 2019, <https://www.newsweek.com/chris-lilley-alleged-trans-racial-character-other-suspect-portrayals-1393171>; Patrick Marlborough, ‘Why Australia Won’t Face Up to a Problem Like Chris Lilley’, Junkee,4 July 2017, <https://junkee.com/chris-lilley-blackface-jonah/110989>; and ‘Jonah From Tonga: Community Takes to Social Media to Share Disappointment at Stereotypes’, ABC News, 12 June 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-06-12/jonah-from-tonga-social-media-reaction/5518516>, all accessed 24 August 2020. With the recent publicity around the removal of four of his shows from Netflix’s platform, and an increasing reluctance from producers to green-light comedy that could be deemed racially insensitive, it may be that we have seen the last of blackface on Australian TV for a long time.

Reflecting and listening

For over 150 years, blackface has been a feature of Australian theatre, film and television. As the practice was both originally imported from overseas and most prominently opposed in the US, many Australians have come to see it as mostly a foreign construct, one whose negative cultural baggage we are safely insulated from. However, Australia has its own blackface tradition, its own black population who were depicted in demeaning and humiliating ways, its own black actors who were passed over for roles, and its own black critics (who were usually ignored). Australia also still retains its own legal protections for blackface – the courts ruled that Beers’ King Billy Cokebottle routine was shielded from prosecution under Section 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act as an ‘artistic work’.[56]See Karina Marlow, ‘A History of Section 18C and the Racial Discrimination Act’, NITV News, 18 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2016/08/16/history-section-18c-and-racial-discrimination-act>, accessed 24 August 2020.

It seems unlikely that any performer will appear in blackface on Australian television, film, stage, radio or theatre in the immediate future. However, considering this country’s history of enthusiasm for the practice, even after well-publicised objections in the 1970s and beyond, there is no guarantee that this will not change in the future, unless adjustments are made to the traditional production models of and critical discourse surrounding Australian television – in particular, to not just give black people space to talk, but to seriously listen to what they are saying.[57]For more on this topic, see Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020.

The author would like to thank the many colleagues who gave feedback on this article.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Jake Kanter, ‘Netflix Removes Chris Lilley Shows, but BBC Stands by Comedian – Including N-word Blackface Sketch’, Deadline,10 June 2020, <https://deadline.com/2020/06/netflix-bbc-chris-lilley-smouse-1202955205/>, accessed 7 July 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Leah Asmelash, ‘How Black Lives Matter Went from a Hashtag to a Global Rallying Cry’, CNN, 26 July 2020, <https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/26/us/black-lives-matter-explainer-trnd/index.html>, accessed 15 August 2020. |

| 3 | See, for example, Tyler Jenke, ‘Chris Lilley Under Fire for Sharing Controversial Blackface Video on Social Media’, The Brag, 30 July 2017, <https://thebrag.com/chris-lilley-under-fire-for-sharing-blackface-video-on-social-media/>, accessed 15 August 2020. |

| 4 | For the purpose of this discussion, I am concentrating on blackface, rather than associated issues of historical whitewashing, colourism, yellowface and blackvoice; these will be touched on in passing, but are not the focus of the piece. |

| 5 | See, for example, Maxine Beneba Clarke, ‘White Australia Has a Blackface History’, Overland, no. 199, Winter 2010, available at <https://overland.org.au/previous-issues/issue-199/feature-maxine-clarke/>; Morgan Godfrey, ‘Jonah from Tonga: The Modern Minstrel Show?’, The Guardian, 23 April 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/23/jonah-from-tonga-the-modern-minstrel-show>; Liz McNiven, ‘A Short History of Indigenous Filmmaking’, australianscreen <https://aso.gov.au/titles/collections/indigenous-filmmaking/>, all accessed 24 August 2020; and Marcia Langton, ‘Well I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television …’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and About Aboriginal People and Things, Australian Film Commission, North Sydney, NSW, 1993. |

| 6 | John Strausbaugh, quoted in Sean Illing, ‘The Complicated, Always Racist History of Blackface’, Vox, 17 February 2019, <https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/2/11/18215370/blackface-virginia-ralph-northam-american-history>, accessed 20 August 2020. |

| 7 | See TV guide, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 January 1987, p. 34. |

| 8 | See Joyce Morgan, ‘Lashwood, Harold Francis (Hal) (1915–1992)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2016, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lashwood-harold-francis-hal-17116/>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 9 | See ‘Ladies and Gentlemen … Be Seated’, ABC Weekly, vol. 20, no. 26, 25 June 1958, p. 9, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1436714371>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 10 | Hal Lashwood, quoted in ‘Simple Appeal of Show’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1958, p. 9. |

| 11 | In the episode, Robeson sang several songs to a multiracial group of children. See ‘Television Topics’, The Biz, 21 December 1960, p. 8, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article190740891>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 12 | ‘Simple Appeal of Show’, op. cit. |

| 13 | See Max Harris, ‘A New Cultural Deal?’, The Bulletin, 28 October 1961, p. 32, available at <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-679975519/view?partId=nla.obj-680027263#page/n31/mode/1up>, accessed 15 August 2020. |

| 14 | ‘Negroes Defamed’, Tribune, 15 April 1959, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article236739624>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 15 | See ‘The Evolution of Vaudeville’, The Age, 31 May 1941, p. 11, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/205149923>; and Gary Le Gallant, ‘Minstrelsy in Australia: A Brief Overview’, Warren Fahey’s Australian Folklore Unit, 14 May 1986, <https://www.warrenfahey.com.au/enter-the-collection/the-collection-m-z/minstrelsy/>, both accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 16 | See Margaret Bridson Cribb, ‘Fadden, Sir Arthur William (1894–1973)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1996, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fadden-sir-arthur-william-10141>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 17 | See ‘Entertainments’, The Daily Herald, 12 November 1917, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article105440192>, accessed 17 July 2020. |

| 18 | See ‘Australia Bars Negroes’, Variety, 2 May 1928, p. 1. |

| 19 | See Josephine O’Neill & Barrett Fleming, ‘A King Honoured Him’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1957, p. 9. |

| 20 | The most common defence was exemplified in 1987 by Ken Jeacle, promoter for a stage version of The Black and White Minstrel Show, who told The Canberra Times:‘This show is purely and simply a character musical variety show. The black makeup is purely and simply a character makeup. And it’s not even black, it’s brown.’ Jeacle, quoted in Karen Middleton, ‘Black and White Minstrel Show’, The Canberra Times, 17 September 1987, The Good Times lift-out p. 11, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122122468>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 21 | See Richard Waterhouse, From Minstrel Show to Vaudeville: The Australian Popular Stage, 1788–1914, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW, 1990. |

| 22 | Lashwood, quoted in ‘Simple Appeal of Show’, op. cit. |

| 23 | See David T Smith, ‘Why Isn’t Blackface Taboo for Australians?’, The New York Times, 4 November 2016 <https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/08/opinion/why-isnt-blackface-taboo-for-australians.html>, accessed 17 August 2020. |

| 24 | See Bruce Lawrence Dennett, ‘The Genesis of Indigenous Australian Characterisations in Feature Films’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, May 2012, available at <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b9b5/44fe0d25f59482044b1be32f7362bd042903.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 25 | See Richard Fotheringham (ed.), Australian Plays for the Colonial Stage: 1834–1899, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld, 2006, p. 18, fn. 4. |

| 26 | Aboriginal trackers appear in the first feature made in Australia, The Story of the Kelly Gang (Charles Tait, 1906), but it is difficult to tell whether they are played by white performers in blackface or Aboriginal actors. See Ina Bertrand & William D Routt, ‘The Picture that Will Live Forever’: The Story of the Kelly Gang, The Moving Image series, no. 8, ATOM, St Kilda, Vic., 2007. |

| 27 | See Anna Kelsey-Sugg & Annabelle Quince, ‘Watershed Moments in Indigenous Australia’s Struggle to Be Heard’, ABC Radio National, 4 July 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-04/complex-history-of-indigenous-and-non-indigenous-australia/9930944>, accessed 20 August 2020. |

| 28 | See ‘Entertainments’, The Brisbane Courier,3 April 1911, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19699763>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 29 | See, ‘On Location in the Coral Sea: Filming Typhoon Treasure’, The Telegraph (Brisbane), 18 December 1937, p. 18, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article184100208>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 30 | See Dennett, op. cit.; and Benjamin Miller, ‘The Mirror of Whiteness: Blackface in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, Spectres, Screens, Shadows, Mirrors: Special Issue, 2007 <https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/10252>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 31 | Despite this progress, Aboriginal performers were still subjected to discriminatory treatment. In 1951, an Actors’ Equity campaign – led by none other than Lashwood – protested against Indigenous extras being paid less than whites on the feature film Kangaroo (Lewis Milestone, 1952). See ‘Aboriginal Actors’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1951, p. 5. In addition, Aboriginal performers sometimes had to get government permission to accept work; see, for example, Peter Forrest, ‘Tudawali, Robert (1929–1967)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2002 <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/tudawali-robert-11889>, accessed 28 August 2020. |

| 32 | Maggie was based on the real-life Aboriginal bushranger Mary Ann Bugg, who routinely inspired characters in films played by white actors in blackface – for instance, Ruby Butler’s performance as ‘Sunday’ in Thunderbolt (Jack Gavin, 1910), possibly the first depiction of a real-life Aboriginal person in a film. |

| 33 | Not all black actors in early Australian television were Aboriginal. Harry Willis, an Australian of Jamaican descent, was cast as a Maori chief in an episode of ATN-7’s 1962 historical serial Jonah, and African-American dancer Joe Jenkins played lead roles in a number of TV dramas for the ABC, including a 1960 adaptation of The Emperor Jones. Jenkins was also a regular on the prime-time 1961 ABC variety show Just Barbara, which starred African-American singer Barbara Virgil, and Willis hosted the 1958 ABC variety show Aloha Hawaii – indicating that Australian television networks may have been more willing to showcase black talent if it was non-Aboriginal. |

| 34 | See Alan Attwood, ‘The Case of Bony Is Not All Black and White’, The Sunday Age, 30 June 1991, p. 9. |

| 35 | See Sue Milliken, Selective Memory: A Life in Film, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, Vic., 2018. |

| 36 | See ‘Native Girl Topless in Film Scene’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 1967, p. 32. |

| 37 | Ed Deveraux, quoted in Josephine O’Neill, ‘How an Actor Went Native …’, The Sun–Herald,3 December 1967, p. 106. |

| 38 | Ben Holgate, ‘Take Two on Black Cinema’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 October 1995, p. 17. |

| 39 | See, for example, Don Storey, ‘Boney’, Classic Australian Television, 2013, , accessed 20 August 2020. |

| 40 | Bob Maza, quoted in Lenore Nicklin, ‘Black Is White and White Is Black’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1972, p. 7. |

| 41 | Danielle Talbot, ‘TV’s New Deal: White Is White and Black Is Black’, The Age, 26 June 1991, p. 1. |

| 42 | See Terri Janke, Pathways & Protocols: A Filmmaker’s Guide to Working with Indigenous People, Culture and Concepts, Screen Australia, Sydney, NSW, 2009. |

| 43 | See John van Tiggelen, ‘Call This Funny?’, Good Weekend, 6 October 2001, pp. 31–4. |

| 44 | See TV guide, Now, 2–8 October 1994, p. 62. |

| 45 | See Karen Lyon, ‘Footy Show’s Black-face Gag Sparks Storm of Protest over Racism’, The Age, 26 March 1999, p. 3. |

| 46 | See Karen Austin, ‘Aboriginal Humour: An Investigation into the Nature and Purposes of Indigenous Australian Performance Humour and Its Contributions to Australian Culture’, PhDthesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, August 2017, available at <https://flex.flinders.edu.au/file/663b8af3-5a52-465f-851109faea5ec821/1/08082017%20THESIS%20AUSTIN%202017%283%29.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 47 | See Sam Duncan, ‘When Comedy Was Anything but Politically Correct: As Comedians Mourn the Death of Australian Jokes, We Take a Look Back at Old Sketches That Would Cause Outrage Today’, Daily Mail Australia, 2 May 2018 <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5680605/The-old-Australian-comedy-sketches-NEVER-away-today-political-correctness.html>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 48 | See Matt Condon, ‘Sultana of Sport’, Now, 2–8 July 1995, pp. 8–9. |

| 49 | See ‘Monte Dwyer Sizzle’, YouTube, 4 December 2011, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cE930rIs36E>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 50 | Chas Licciardello, in ‘Is Blackface on Australian TV Really That Bad?’, YouTube, 30 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qylLWyjxZrs>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 51 | See Meg Watson, ‘Here’s What Happened When Australia Defended Blackface in 2009’, Junkee, 23 February 2016, <https://junkee.com/heres-happened-australia-defended-blackface-2009/73879>; Meg Watson, ‘Here Are All the High-profile Australians Who’ve Defended Blackface Lately’, Junkee, 22 February 2016, <https://junkee.com/here-are-all-the-high-profile-australians-who-defended-blackface-today/73840>; and ‘Hey Hey It’s Time to Talk About Blackface!’, It’s Not a Race, Radio National, 31 May 2017, <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/itsnotarace/hey-hey-its-time-to-talk -about-blackface/8568856>, all accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 52 | Many episodes from these shows have since been withdrawn from streaming services. See Christi Carras, ‘These TV Shows Recently Removed Blackface Episodes. Here’s What You Need to Know’, Los Angeles Times, 30 June 2020, <https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-06-30/blackface-episodes-pulled-the-office-golden-girls-30-rock?>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 53 | Chris Lilley, quoted in Eric Spitznagel, ‘Q&A: Chris Lilley on Drag, Blackface, Teenage Girls & Confrontational Comedy’, Esquire, 14 November 2013, <https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/interviews/a25930/chris-lilley-interview/>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 54 | ibid. |

| 55 | See, for example, Seini F Taumoepeau, ‘Chris Lilley’s Jonah Is Not from Tonga, I Am. It’s Time to Dismantle Racist Brownface Stereotypes’, The Guardian, 12 June 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/12/chris-lilleys-jonah-is-not-from-tonga-i-am-its-time-to-dismantle-racist-brownface-stereotypes>; Dory Jackson, ‘Chris Lilley Accused of Blackface in Lunatics: Examining the Comedian’s Other Controversial Characters’, Newsweek,11 April 2019, <https://www.newsweek.com/chris-lilley-alleged-trans-racial-character-other-suspect-portrayals-1393171>; Patrick Marlborough, ‘Why Australia Won’t Face Up to a Problem Like Chris Lilley’, Junkee,4 July 2017, <https://junkee.com/chris-lilley-blackface-jonah/110989>; and ‘Jonah From Tonga: Community Takes to Social Media to Share Disappointment at Stereotypes’, ABC News, 12 June 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-06-12/jonah-from-tonga-social-media-reaction/5518516>, all accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 56 | See Karina Marlow, ‘A History of Section 18C and the Racial Discrimination Act’, NITV News, 18 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2016/08/16/history-section-18c-and-racial-discrimination-act>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 57 | For more on this topic, see Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. |