Australia’s independent videogames scene is globally unique: here, there is very little to be independent from. Most other game development hubs – places like Toronto, London, Kyoto, Seattle – have a ‘big end’ of town, where major companies provide both steady employment for a large body of workers and a kind of flat palate of establishment taste to rebel against. Australia had this once, in the form of companies with big international investment and contracts to fulfil. Then a mixture of local mismanagement and the global financial crisis meant that all but a few sold up, shut down and moved out.[1]For more on the post-GFC videogames landscape in Australia, see John Banks & Stuart Cunningham, ‘Games Production in Australia: Adapting to Precariousness’, in Michael Curtin & Kevin Sanson (eds), Precarious Creativity: Global Media, Local Labor, University of California Press, Oakland, 2016, pp. 186–99.

All that was left was independence. And so Australia’s videogames culture is now defined not by any kind of rebellion against the Man, but by gradations of independence – from financial to aesthetic to labour conditions and back again. When what constitutes a big company is just twenty employees strong, that certainly makes for an independent videogames scene that looks nothing like its counterparts elsewhere in the world.

Often, that difference has resulted in creative success – particularly in the freedom to experiment and switch up the rules, whether in terms of quality of narrative (2018’s Florence, by Mountains); niche, old-fashioned experiences (2017’s Hollow Knight, by Team Cherry); or experiments with revenue streams (such as 2014’s microtransaction- and sponsorship-led Crossy Road, by Hipster Whale). Australia has led the world across each at various points in recent times.

Today, Australia produces some of the most varied and unusual independent videogames in the world. There is always more to challenge, more to question – more independence to be found. From memes to nostalgia, geographic reflection to comedy, here are some recent noteworthy successes.

Red Desert Render’s landscapes … are distinctively Australian: foregrounds filled with familiar dry scrub, and distances populated by hazy blue mountains.

Untitled Goose Game

House House, 2019

Few videogames ever achieve a place in the zeitgeist the way House House’s Untitled Goose Game has. In late 2019, this modest, Melbourne-made goose was everywhere: in memes, of course, on seemingly every social-media platform, but also on protest signs (against Brexit, against neo-Nazis, against climate change),[2]See, for example, Amrita Khalid, ‘How Untitled Goose Game Became a Left-wing Meme’, Quartz, 20 December 2019,<https://qz.com/1771229/how-untitled-goose-game-became-a-left-wing-meme/>, accessed 25 February 2020. on stage with the Muppets,[3]See Nicole Carpenter, ‘I Wish the Untitled Beaker Game Was Real’, Polygon, 13 December 2019, <https://www.polygon.com/game-awards-tga/2019/12/13/21020430/untitled-goose-game-muppet-labs-beaker-collab-tga-2019>, accessed 25 February 2020. and in celebrity endorsements from the likes of venerable pop-punk band Blink-182, and model and Twitter royalty Chrissy Teigen.[4]See Ben Gilbert, ‘Everyone from Chrissy Teigen to Blink-182 Is Freaking Out About a Goose Game – One Look at the Bizarre New Game Explains Why’, Business Insider, 2 October 2019, <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/what-is-the-untitled-goose-game-people-are-talking-about-2019-10> , accessed 25 February 2020.

The appeal of Untitled Goose Game, which perhaps comes down to cathartic wish fulfilment, is summed up fairly well in its official tagline: ‘It’s a lovely day in the village, and you are a horrible goose.’[5]See Untitled Goose Game official website, <https://goose.game>, accessed 25 February 2020. On a Nintendo Switch, PC, Mac, PlayStation 4 (PS4) or Xbox, players take on the role of said horrible goose and terrorise a small pseudo-British village by stealing its inhabitants’ possessions, inconveniencing them in their daily routines and generally being quite mean.

House House initially struck on the game idea as a joke (Wouldn’t it be funny to make a game about a goose?) and couldn’t decide on a name. By the end of 2019, though, its publisher, the Portland-based Panic Inc., had announced the game had sold more than 1 million copies.[6]See Cody Peterson, ‘Untitled Goose Game Passes One Million Units Sold in Three Months’, Screen Rant, 31 December 2019,<https://screenrant.com/untitled-goose-game-number-sold-one-million/>, accessed 25 February 2020. It is, I think, the kind of game that could only have been made in Australia, and possibly particularly Melbourne – House House is a product not so much of the global videogames industry, but rather of a city that values an interest in culture and creativity. The four developers – Jacob Strasser, Stuart Gillespie-Cook, Michael McMaster and Nico Disseldorp – studied fine arts and filmmaking, not coding or 3D modelling.[7]See ‘House House: Docklands Spaces and Renew Australia Alumni Making Big Waves in the Gaming Industry’, Renew Australia website, 30 October 2019, <https://www.renewaustralia.org/2019/10/4-questions-with-house-house-docklands-spaces-and-renew-australia-alumni-making-big-waves-in-the-gaming-industry>, accessed 25 February 2020.

Untitled Goose Game was crowned Game of the Year at both the 2019 Australian Game Developers Awards and the 2020 DICE Awards; at the time of writing, it is also a finalist for two awards at the Independent Games Festival, perhaps the most prestigious international indie-game event around.

I must also admit to not being dispassionate here, as I worked with House House to arrange the piano preludes of classical composer Claude Debussy to dynamically score the game. Another element unusual for videogames, the music was inspired by how popular classical pieces were used as a kind of vernacular soundtrack in the early years of silent film. It has been truly surreal to see this eccentric local creation become a global hit.

Unusually for a game of any size, Paperbark employed the expertise of a ‘resident ecologist’ to ensure every square centimetre of the game’s environment would be exciting, accurate and educational.

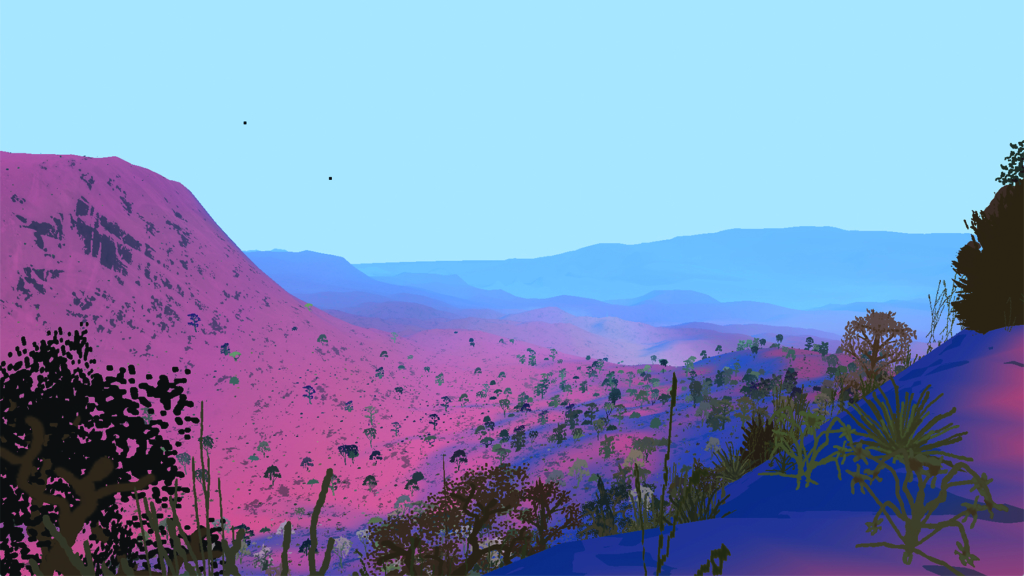

Red Desert Render

Ian MacLarty, 2019

https://ianmaclarty.itch.io/red-desert-render

Ian MacLarty has, for some time now, been among the most prolific and interesting solo game developers working in Australia, and his 2019 output proved to be no different. Along with dexterous PC/Mac/Android/iOS puzzle game JUMPGRID, that year saw him release Red Desert Render, an idiosyncratic reflection on Australia’s landscape for PC, Mac and Linux.

The genesis of Red Desert Render lies in Rockstar Games’ blockbuster western Red Dead Redemption 2 (RDR2) from 2018. MacLarty, along with an informal group of Australian game developers calling themselves ‘The Grannies’, gained a small amount of notoriety online for pushing RDR2 to its limits, exploring – via glitches and exploits – environments in the game that the original developers thought would never be reached. When you look into the horizon in a big open-world title like RDR2, you usually cannot go there; it is an illusion of geography, a non-space suggesting that the landscape is bigger than it actually is. The Grannies, however, determinedly found ways to force the game into permitting them into these no-go zones and discover this digital world’s behind-the-scenes areas. These were environments at the ‘uncanny valley’[8]See Jeremy Hsu, ‘Why “Uncanny Valley” Human Look-alikes Put Us on Edge’, Scientific American, 3 April 2012, <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-uncanny-valley-human-look-alikes-put-us-on-edge/> , accessed 25 February 2020. intersection of photoreal geography and glitched digital non-spaces. The adventures of MacLarty and his compatriots, captured in screenshots and video, were ghostly and strangely exciting.[9]See Luke Plunkett, ‘Red Dead Online Players Escape Game World, Find Beautiful Desert Paradise’, Kotaku, 26 June 2019, <https://www.kotaku.com.au/2019/06/red-dead-online-players-escape-game-world-find-beautiful-desert-paradise/>, accessed 25 February 2020.

Red Desert Render is MacLarty’s creative response to these experiences, capturing some of the unpredictability and otherworldliness of the environments they discovered. The player can forward-roll down hills, or take a bath to grant temporary – and disorienting – flight abilities. Red Desert Render’s landscapes, however, are far from RDR2’s stereotypical American west. Instead, they are distinctively Australian: foregrounds filled with familiar dry scrub, and distances populated by hazy blue mountains.

Another point of interest is that MacLarty is using an intriguing pay-what-you-want model for Red Desert Render. Spend US$20 or more on it and he’ll custom-generate a unique world for you to explore, available to nobody else. A bespoke place for a bespoke videogame.

It is all very cute, and, if you are a pigeon fancier, the game’s charm will already be quite strong. However, Pigeon Game’s genius lies in its playful subversion of the stock-standard dude-bro tech culture that still underpins many of today’s videogames.

Frog Detective series

Worm Club, 2018–2019

Videogames are not often funny. There are pockets of humour, yes – particularly the absurdist English PC homebrew scene of the 1980s, or more recently in deliberately comedic games like Jazzpunk (Necrophone Games, 2014). Otherwise, videogames have traditionally been much better at being exciting, perplexing or surprising than at humour.

Yet the two Frog Detective games – whose full titles are Grace Bruxner Presents the Haunted Island, a Frog Detective Game (2018) and Frog Detective 2: The Case of the Invisible Wizard (2019), and which are playable on PC or Mac – are very funny. They star the titular Frog Detective, whose attitude to crime is a mixture of consternation and confusion; players solve extremely low-stakes mysteries (Is there a ghost on the island? Who destroyed the Invisible Wizard’s welcome parade?) by chatting with a cast of good-humoured animal characters who are largely just happy to have someone to speak to at all (or sing to, in the case of Mary the Rhinoceros). The game’s hilarious dialogue, by the titular Grace Bruxner, is best read out loud, in company and in silly voices while our hero – who, let it be known, cannot wear hats – comes to terms with the superior crime-solving abilities of Lobster Cop.

(Like Untitled Goose Game, I also provided music for both Frog Detective titles, which, although not influencing my view of them as genuinely funny games, does reinforce my own track record of only composing for animal-themed Australian-made indie games.)

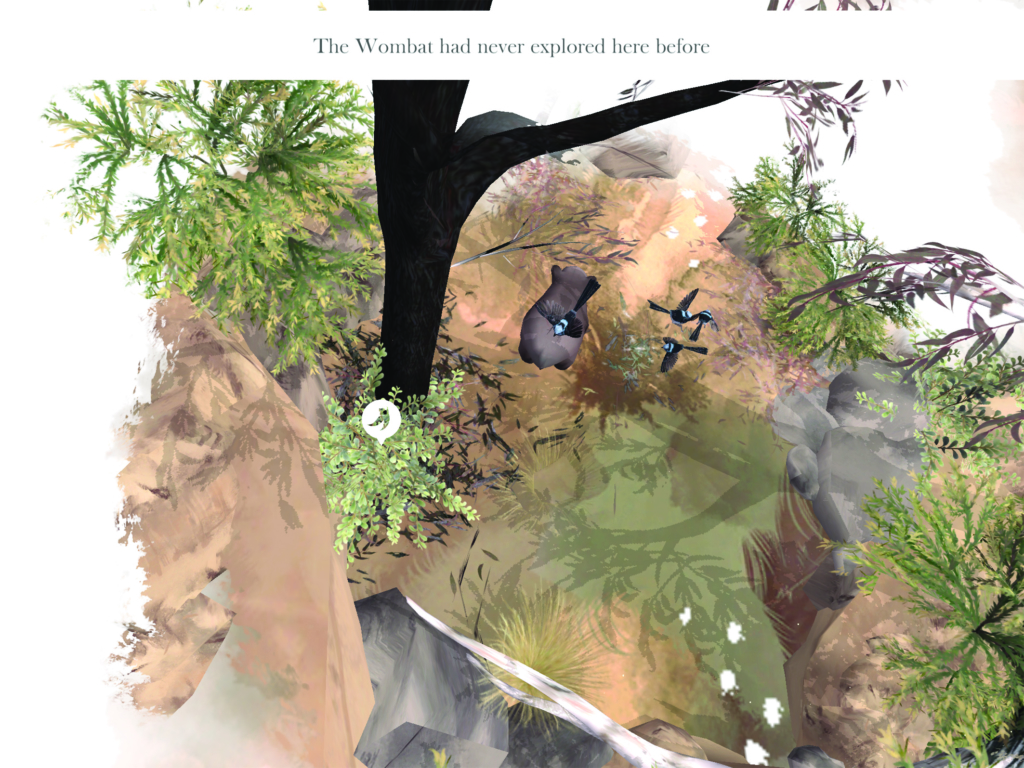

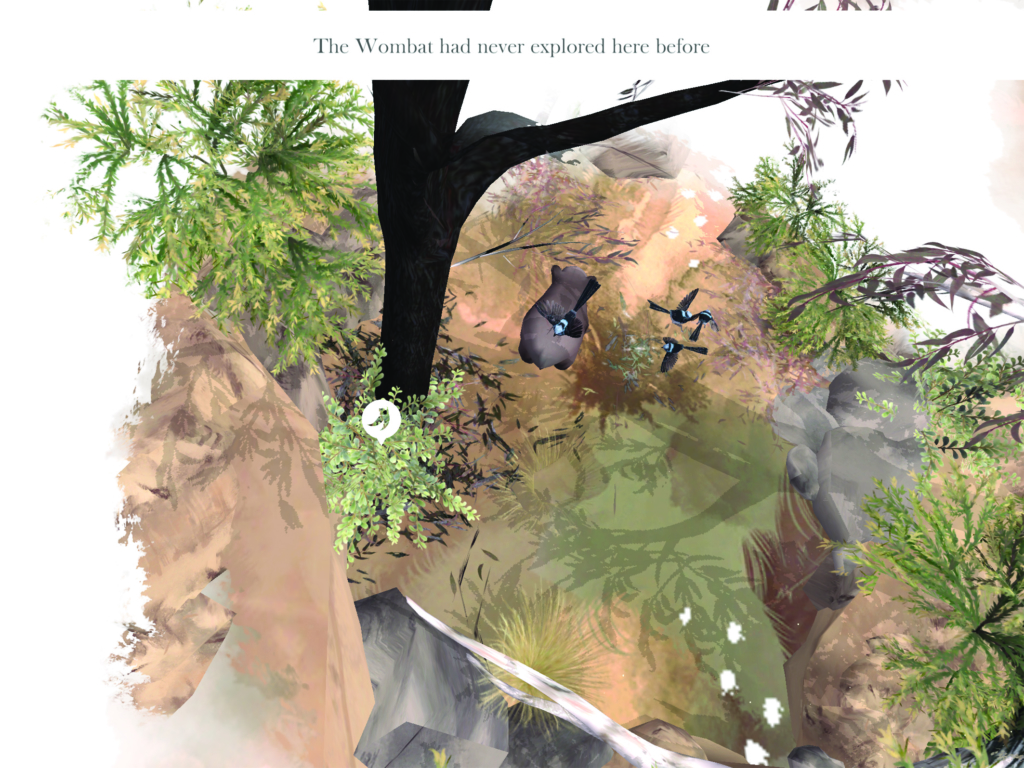

Paperbark

Paper House, 2018

Even now, two years after its release, iOS/PC/Mac game Paperbark remains the most carefully authentic representation of the Australian landscape in videogames. Inspired by classic children’s picture books like Possum Magic, Blinky Bill and Diary of a Wombat, the game began its life as the final-year university project of creators Terry Burdak, Nina Bennett and Ryan Boulton.[10]See Johnny Lieu, ‘The iOS Game That Lets You Explore Australia as a Wombat’, Mashable, 2 November 2017, <https://mashable.com/2017/11/02/paperbark-game-interview-pax/>, accessed 25 February 2020. However, Paperbark so clearly filled a significant gap in videogames culture that the trio – now operating as the collective Paper House – saw it through to commercial release after several years of dedicated development post-graduation.

Paperbark tells a quiet tale about a curious and friendly wombat wandering around meticulously recreated scrub on a hot summer’s day. The picture-book inspiration is not limited to the game’s imagery, but carries over to the touching and meandering story, which is narrated by Georgia Maq of Melbourne indie rock band Camp Cope.

The game offers players the opportunity to collect in-game stickers of native flora and fauna, as well as an array of sounds immediately recognisable to anyone who has spent time in Australia’s bushland. Unusually for a game of any size – let alone a small, independently made release – Paperbark employed the expertise of a ‘resident ecologist’ (Dr Emma Razeng) to ensure every square centimetre of the game’s environment would be exciting, accurate and educational.

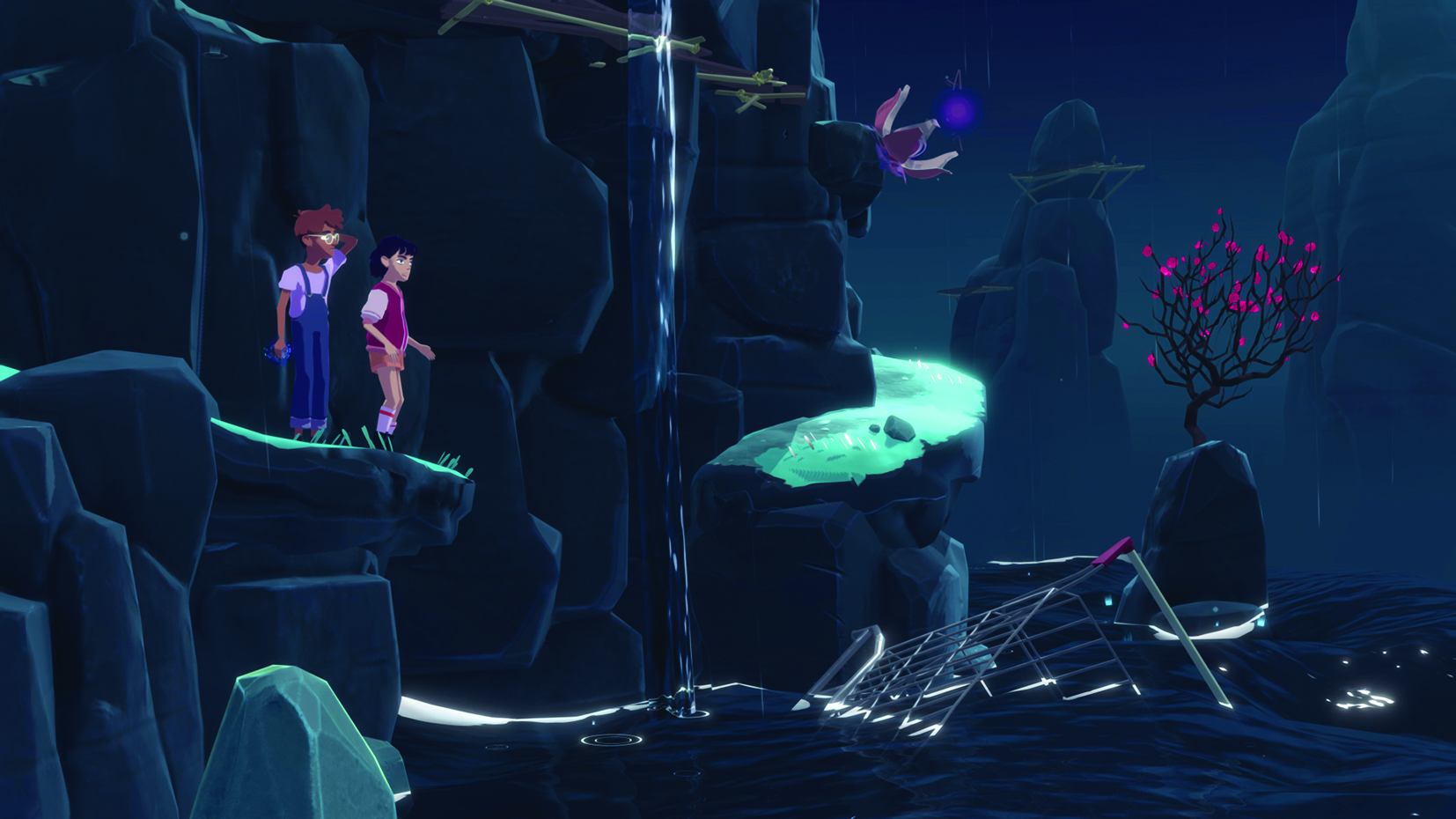

The Gardens Between

The Voxel Agents, 2018

The Gardens Between is a puzzle videogame for PC, Mac, Switch, PS4, Xbox and iOS with a unique system of control: as the players move, so does time. If the player halts, time pauses. If the player goes backwards, time follows suit. It allows for a genuinely unusual form of activity in a videogame that forces the player to think across multiple dimensions of movement, interaction and chronology.

That The Gardens Between uses this game mechanic to tell a nostalgic story – written by Brooke Maggs, now narrative designer on Remedy Entertainment’s Control, one of the biggest videogames of 2019 – about childhood, friendship and loss only amplifies its appeal. The striking art style is also reinforced by local musician and Triple J announcer Tim Shiel’s poignant soundtrack.

The Gardens Between is one of those rare works that combines a narrative theme with a way of interacting, and a way of being, in a videogame. What does it mean to return to the past, to push back through our memories? Is the past a better place only via the lens of a backwards glance? This is a game of childhood memory palaces, transformed into responsive mystery boxes.

Pigeon Game

Leura Smith, 2018

https://smitleu.itch.io/pigeon-game

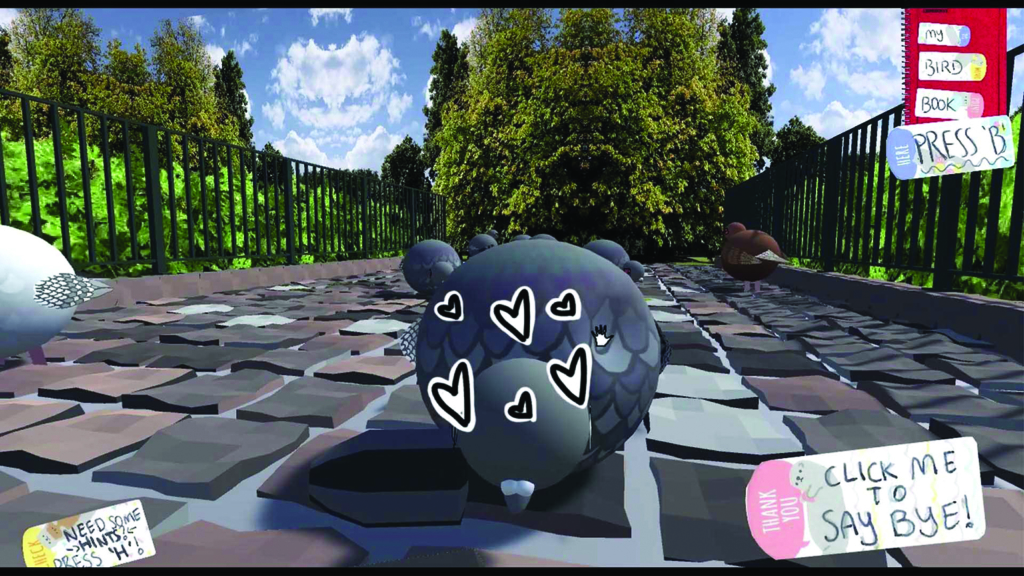

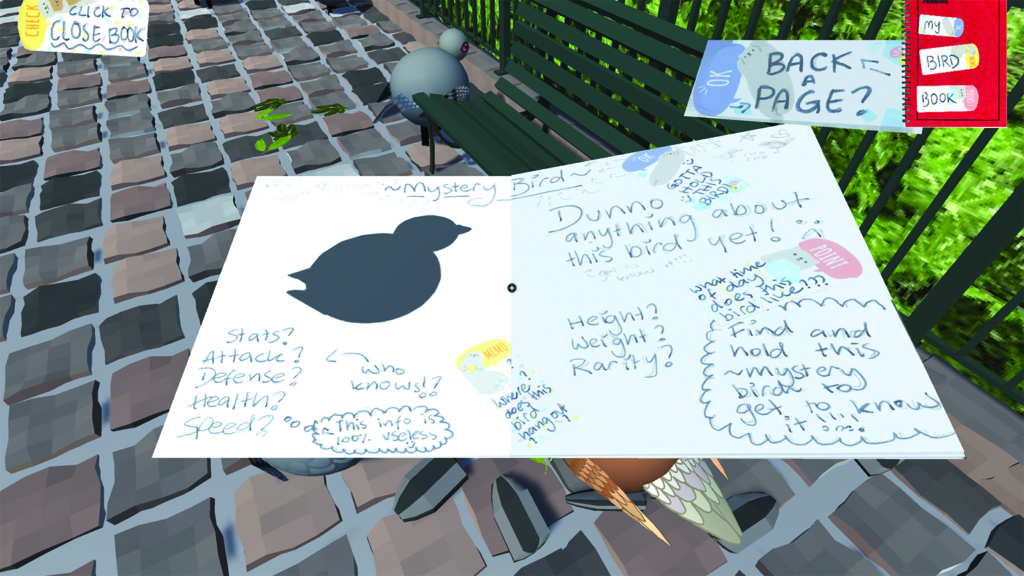

Pigeon Game is precisely the sort of short and endearingly strange independent game made possible by the dramatic shifts in game production and distribution over the last decade. Whereas making games was, for a time, an incredibly expensive endeavour involving the licensing of production software and the physical dissemination of the end result, now both of these things can be done for very little cost using free software and platforms. This has meant big changes in what kinds of games we have seen developed – across subject matter, length (lower costs mean less emphasis on expense-justifying substance) and styles of production.

Pigeon Game – for PC, Mac and Linux, with a mobile version pending – was made by Leura Smith while she was a young game design university student in Melbourne. It is free (or cheap, through a name-your-own-price download model), and it is very short. Its objective is simple: you follow bulbous and dimwitted pigeons around a courtyard, before picking one up and holding it. Once held, the pigeon can be rolled around the player’s hands like a softly cooing water balloon. That’s it – that’s the game.

It is all very cute, and, if you are a pigeon fancier, the game’s charm will already be quite strong. However, Pigeon Game’s genius lies in its playful subversion of the stock-standard dude-bro tech culture that still underpins many of today’s videogames.

Understanding this all comes back to something called ‘assets’. Today, when making a videogame using free software like Unity or Unreal (two common platforms), designers can take shortcuts by using pre-made assets provided either free or at cost. Imagine that you are making a first-person shooter but can’t budget a week of time accurately 3D-modelling a gun to use in the game. Instead of reinventing the wheel, you can easily purchase a pre-prepared gun asset and pop it into your game in minutes. The same can be done with almost anything, forming a practical catalogue of standard-issue objects to make videogames out of. Houses, trees, even characters … and boobs.

Smith’s unusually bulbous pigeons have their own secret: they are repurposed from breasts available as stock assets for otherwise-uncritical game developers to include as literal sexualised objects in their games.[11]See Meghann O’Neill, ‘Games Are Sometimes Better When They Aren’t All About Saving the World’, Junkee, 18 December 2018, <https://junkee.com/personal-games/187345> ; and ‘Freeplay Parallels 2018’, YouTube, 13 January 2019, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edEWV0UNpx4>, both accessed 3 March 2020. With Pigeon Game, Smith has not only created a game that is the antithesis of masculine videogames culture – it is not violent, nor is it driven by a honed rules-and-reward gameplay system – but also used its own tools to do so. This is not a piece of overt commentary, but rather an ingenious bricolage that appropriates elements of a dominant culture to make something infinitely more interesting and provocative.

These six games only begin to reveal the complex layers of independent creativity apparent in Australia’s videogames communities. They are smart, critical and aware of the world they take place in. But so are so many others.

Just a brief look at some of the more interesting games currently being made in Australia emphasises the depth of the creative work being done here. Take Wayward Strand (Ghost Pattern, 2019), a game about a young girl visiting a 1970s Australian hospital – that’s also a ship floating in mid-air – for the first time. The game unfolds in real time, too, meaning there’s no guarantee that any character will stay where you’ve left them, or that you’ll be in the right place at the right time to catch a key event. Dead Static Drive (Team Fanclub) is a forthcoming highlight that combines the old-school feel of the original Grand Theft Auto (BMG Interactive, 1997) with a kind of eldritch horror. It’s the cool of Drive (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2011) or Bullitt (Peter Yates, 1968), the dreaminess of David Lynch, and the dread of John Carpenter rolled into one. Or take Wood & Weather, Paper House’s recently announced toy-box cityscape game about climate change. Or Heavenly Bodies, 2pt Interactive’s upcoming cooperative game in which players take control of Sputnik-era astronauts fumbling around in zero gravity – equal parts hilarious and horrifying. Even if they aren’t all set in Australia, each of these independent videogames is, in one way or another, ineffably Australian. Each takes creative risks and critical approaches to game making in an industry that understands independence in gradations rather than binaries.

Endnotes

| 1 | For more on the post-GFC videogames landscape in Australia, see John Banks & Stuart Cunningham, ‘Games Production in Australia: Adapting to Precariousness’, in Michael Curtin & Kevin Sanson (eds), Precarious Creativity: Global Media, Local Labor, University of California Press, Oakland, 2016, pp. 186–99. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See, for example, Amrita Khalid, ‘How Untitled Goose Game Became a Left-wing Meme’, Quartz, 20 December 2019,<https://qz.com/1771229/how-untitled-goose-game-became-a-left-wing-meme/>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 3 | See Nicole Carpenter, ‘I Wish the Untitled Beaker Game Was Real’, Polygon, 13 December 2019, <https://www.polygon.com/game-awards-tga/2019/12/13/21020430/untitled-goose-game-muppet-labs-beaker-collab-tga-2019>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 4 | See Ben Gilbert, ‘Everyone from Chrissy Teigen to Blink-182 Is Freaking Out About a Goose Game – One Look at the Bizarre New Game Explains Why’, Business Insider, 2 October 2019, <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/what-is-the-untitled-goose-game-people-are-talking-about-2019-10> , accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 5 | See Untitled Goose Game official website, <https://goose.game>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 6 | See Cody Peterson, ‘Untitled Goose Game Passes One Million Units Sold in Three Months’, Screen Rant, 31 December 2019,<https://screenrant.com/untitled-goose-game-number-sold-one-million/>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 7 | See ‘House House: Docklands Spaces and Renew Australia Alumni Making Big Waves in the Gaming Industry’, Renew Australia website, 30 October 2019, <https://www.renewaustralia.org/2019/10/4-questions-with-house-house-docklands-spaces-and-renew-australia-alumni-making-big-waves-in-the-gaming-industry>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 8 | See Jeremy Hsu, ‘Why “Uncanny Valley” Human Look-alikes Put Us on Edge’, Scientific American, 3 April 2012, <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-uncanny-valley-human-look-alikes-put-us-on-edge/> , accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 9 | See Luke Plunkett, ‘Red Dead Online Players Escape Game World, Find Beautiful Desert Paradise’, Kotaku, 26 June 2019, <https://www.kotaku.com.au/2019/06/red-dead-online-players-escape-game-world-find-beautiful-desert-paradise/>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 10 | See Johnny Lieu, ‘The iOS Game That Lets You Explore Australia as a Wombat’, Mashable, 2 November 2017, <https://mashable.com/2017/11/02/paperbark-game-interview-pax/>, accessed 25 February 2020. |

| 11 | See Meghann O’Neill, ‘Games Are Sometimes Better When They Aren’t All About Saving the World’, Junkee, 18 December 2018, <https://junkee.com/personal-games/187345> ; and ‘Freeplay Parallels 2018’, YouTube, 13 January 2019, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edEWV0UNpx4>, both accessed 3 March 2020. |