Over a decade on from its first episode, Underbelly remains the last scripted piece of Australian television to become a true phenomenon. Even before it aired, the series dominated discussion around Australian popular culture. Its first season, which was broadcast from February to May 2008 and was adapted from John Silvester and Andrew Rule’s Leadbelly: Inside Australia’s Underworld Wars, chronicles the wheeling, dealing and, most of all, killing that occurred between Melbourne’s organised crime factions from 1995 to 2004. The success of the franchise – which aired a spin-off miniseries, Underbelly Files: Chopper, as recently as last year – is testament both to our baser desires as viewers (with sex and violence ubiquitous throughout) and a distinctively Australian fascination with the darker aspects of our recent history.

What made Underbelly especially memorable before a single episode hit the screen was its well-publicised legal controversies. An injunction from the Supreme Court of Victoria meant that the series aired in Victoria months after the other states, with edits imposed to keep those in active criminal trials anonymous.[1]See ‘Grave Doubts over Underbelly: Court’, The Age, 8 February 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/grave-doubts-over-underbelly-court-20080208-ge6pc2.html>, accessed 25 February 2019. These complications served to both underline the perceived realism of the series – which hewed closely to salacious news reports from only a few years earlier – and further fuel audience interest already stoked by a formidable marketing spend. With the advent of accessible pirating platforms that allowed Victorian viewers to circumvent the injunction,[2]See Nick Miller, ‘Pirates Promise Underbelly Downloads’, The Age, 13 February 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/technology/pirates-promise-underbelly-downloads-20080213-gds0uk.html>, accessed 25 February 2019. it’s not surprising that the show was everywhere in Australia.

The legal drama that consumed the drama series speaks not only to the show’s popularity, but also, more importantly, to the driving philosophy behind it. Before the series premiered, I recall expecting an Australian take on The Sopranos: morally ambiguous protagonists, commentary on the human condition, character studies wrapped in sex and violence. That would’ve aligned the show with the primary mode of prestige television popular at the time. Instead, Underbelly – in all its iterations, with subsequent seasons drilling back into earlier generations of Aussie criminality – is a cruder take on the post-Sopranos ‘golden age’ television model, stringing together a sequence of notable crimes with, often, only a passing interest in characterisation. The bulk of the series adopts a Wikipedia approach to storytelling, dutifully including significant events that would warrant a subheading or dot point on, say, the ‘Melbourne Gangland Killings’ page. Convicted criminals’ exploits are given prime placement, while unsolved crimes – or those too obscure to make headlines – are left to languish on the margins.

While this model is perhaps precautionary (that is, sticking to established facts to mitigate the threat of legal action), I think it’s key to understanding the series’ appeal. With Australia’s past rarely portrayed prominently in pop culture beyond Ned Kelly and Gallipoli, Underbelly’s success can be – at least partially – credited to its local audience’s desire to see the messier moments of our modern history. And, even if there hasn’t really been an Australian series to follow in Underbelly’s footsteps, this mode of storytelling has seen more than its fair share of imitators on local television in the years since, from Hawke to Molly.

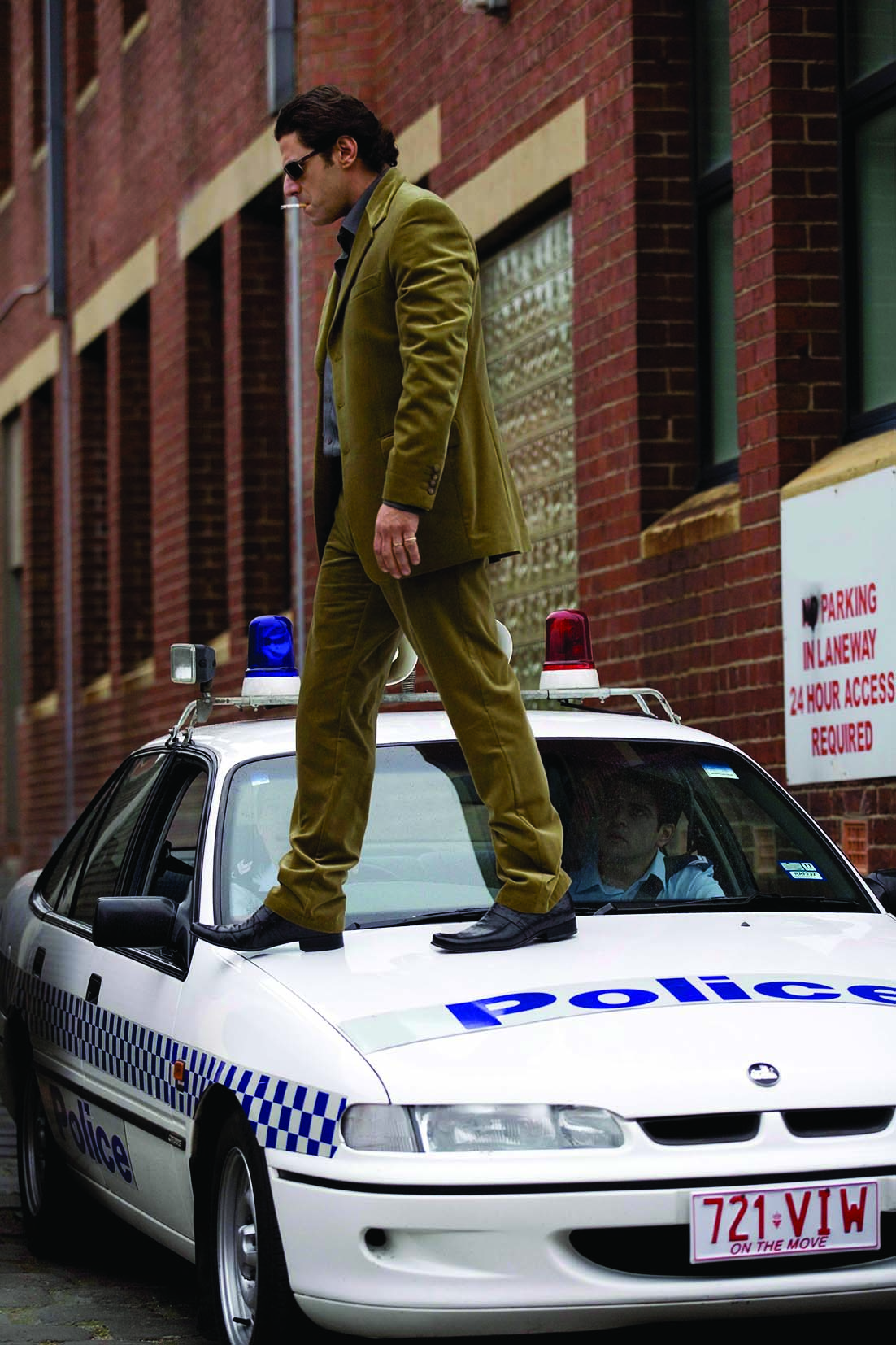

As I rewatch Underbelly with fresh eyes, what stands out is its flop-sweat anxiousness to be liked by Australian audiences. Unlike its more prestigious American contemporaries, Underbelly eschews restraint and ambiguity in favour of attention-grabbing conventions. A blaring soundtrack is filled with contemporary pop songs, and Caroline Craig’s narration clarifies narrative specifics while doling out moral judgement. (Case in point: when Jason Moran, played by Les Hill, is released from prison in the eighth episode of Season 1, she explains that he ‘finished his sentence for being a vicious, brutal, ugly little turd’.) Each episode is dotted with various incidences of sex, drugs and violence, and any ‘boring’ stuff (you know, like dialogue) is often underlined with overexposed, fragmentary step printing.[3]A stuttering style of stop-motion most memorably used in Wong Kar Wai’s 1994 film Chungking Express, employed here for emphasis or to attempt to evoke excitement. Aesthetically, the show strongly evokes the likes of Quentin Tarantino’s early films or Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, except without attaining analogous artistry.

Unlike its more prestigious American contemporaries, Underbelly eschews restraint and ambiguity in favour of attention-grabbing conventions … Each episode is dotted with various incidences of sex, drugs and violence.

Then there’s the nudity. A few years before Game of Thrones weaponised gratuitous nudity, Underbelly ensured that nearly every episode featured female actors (and, very occasionally, male ones) doffing their clothes at the thinnest excuse. Sometimes, it was unnamed extras gyrating in the series’ many strip-club or massage-parlour scenes; just as often, main characters showcased their naughty bits to keep audiences’ eyes glued to the screen. The most notorious example is surely found in the sixth episode of Season 3, subtitled The Golden Mile, in which police officer Debbie Webb (Cheree Cassidy) – whose nakedness would’ve served no real narrative justification – holds a meeting at a nudist beach. This emphasis on sex appeal aligns Underbelly more closely with the more exploitative television shows of the era (think: Californication or Spartacus) than with prestige series like Mad Men or The Wire.

Despite this, I’m not convinced that Underbelly truly fits in with any of the television shows coming out of the States at the time. It’s structurally unusual, for starters: its anthology format, with each season tackling a new era with (mostly) new actors, wasn’t popularised in the US until American Horror Story circa 2011. Meanwhile, the historical subject matter, while far from exceptional in the context of audiovisual narratives, was distinct at the time in both its currency and detail. There are plenty of historical television series and feature-length biopics, but, until Underbelly, few television shows represented recent events in this sort of warts-and-all detail. Indeed, the closest equivalent in American television wouldn’t arrive until 2016 series American Crime Story, the first season of which focused on OJ Simpson’s trial.

Earlier, I mentioned Underbelly’s ‘Wikipedia storytelling’. That approach is hardly restricted to this show; countless Hollywood biographical/historical films have assumed the same dot-point approach to narrative (Bryan Singer’s 2018 Bohemian Rhapsody, Morten Tyldum’s 2014 The Imitation Game, and so on), to varying results. But, when used across up to thirteen episodes in multiple seasons,[4]The first four seasons each had thirteen episodes, while seasons five and six as well as associated spin-off Fat Tony & Co had eight, eight and nine episodes, respectively. the strengths and weaknesses of this storytelling style become very apparent.

Let’s start with the weaknesses. First, there are the sacrifices to narrative coherence necessitated by the artistic decision to cram in every major crime across the time period depicted. Whether it’s the late Season 1 introduction of Keith Faure (Kim Gyngell; the character was unnamed due to the aforementioned injunction), the Les and Brian Kane (Martin Dingle Wall and Tim McCunn) diversion in Season 2, subtitled A Tale of Two Cities, or the shift in focus to Michael ‘Doc’ Kanaan (Ryan Corr) in The Golden Mile, the series frequently diverges from established protagonists for quick detours that tick off big headlines but only have a tangential connection to the core storyline. Then there’s the obligatory tiptoeing around crimes that never produced a conviction. That’s most pronounced in the legally fraught first season, particularly in the showdown between Mick Gatto (Simon Westaway) and Andrew ‘Benji’ Veniamin (Damian Walshe-Howling) that led to the latter’s demise and Gatto’s being charged with murder, for which he was later acquitted. Veniamin’s death is kept off screen, while associated attempts to evoke ambiguity are largely unsuccessful: Gatto comes off as, if not the good guy, then at least innocent.

It’s the same story with the portrayal of The Golden Mile’s John Ibrahim (Firass Dirani). Initially framed as the protagonist of this season, Ibrahim – who’s never been successfully convicted of a crime – floats through the narrative without much agency or purpose. His inclusion in the Kings Cross–centric season is mandated by his notorious profile, but the screenwriters seem adrift when it comes to meaningfully incorporating him into the storyline, splitting the difference by portraying him as both a saint (as when he tries to defuse a violent brawl) and a criminal (as when he dodges conviction for the murder of Talal Assaad, played by Rahel Romahn). This approach to presenting a character as ‘multidimensional’ speaks to the showrunners’ obvious desire for their show to be perceived as authentic; however, for audience members, it’s frequently frustrating.

It’s not all bad news. While Underbelly’s first season particularly suffers from scattershot storytelling, the two subsequent seasons attain a tighter focus despite having expanded the ‘core’ cast. These prequel seasons – centring on events in Melbourne and Sydney from 1976 to 1987 (A Tale of Two Cities) and Kings Cross from 1988 to 1999 (The Golden Mile) – did have the luxury of more legal freedom than Season 1, given they’re dealing with events from decades, not years, prior. But I’d argue that the real strength of these seasons is that they use the theme of police corruption not only as a narrative throughline (featuring returning actors), but also to examine systemic cultural and logistical issues that allowed organised crime to thrive, rather than being reduced to isolated pockets of greed and vice.

The centrality of such corruption is significant – and rare. As critic Lauren Carroll Harris has argued in Daily Review, Aussie crime shows and movies typically offer ‘a simplistic, cops-and-robbers, goodies-and-baddies view of the police’, with corruption only depicted as ‘individual and isolated incidents of illegitimate policing’.[5]Lauren Carroll Harris, ‘What Australian Screen Stories Get Wrong About Police, Crime and Brutality’, Daily Review, 1 December 2016, <https://dailyreview.com.au/australian-screen-stories-get-wrong-police-crime-brutality/53132/>, accessed 25 February 2019. Though that dynamic was maintained, somewhat implausibly, in Underbelly’s first season, both subsequent seasons use findings from the 1995–1997 Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service (seen in The Golden Mile) to present a portrait of a deeply corrupt and misogynistic[6]And every other kind of -phobic you could think of. Case in point: the death of The Golden Mile’s trans sex worker Wanda (Mitch Bartlett), who is treated with disdain by the officers who discover her body. culture at the core of Australia’s justice system.

The second and third seasons credit the success of the criminals featured to neither genius nor dumb luck, but rather the tacit permission of a justice system content to look the other way … for a price.

The second and third seasons credit the success of the criminals featured to neither genius nor dumb luck, but rather the tacit permission of a justice system content to look the other way … for a price. While I’m not completely convinced by the contemporaneous claims that Underbelly glamorised crime or violence,[7]See Richard Clune & Yoni Bashan, ‘Underbelly Gangster Glamour Wears Off’, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 January 2010, <https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/underbelly-gangster-glamour-wears-off/news-story/7f39da23c8aa04c5c2d2a82fa80745e1>, accessed 25 February 2019. the portrayed exploits of the convicted criminals do tend to pale in comparison to the nefariousness of those tasked with stopping them. It’s telling that some of the series’ most affecting moments involve police officers, whether it’s the murder of A Tale of Two Cities’ corrupt lawyer Brian Alexander (Damian de Montemas) or the sexual assault of The Golden Mile’s rookie detective Claudia Campanelli (Megan Drury).

Though reports at the time suggested that the fourth season, Razor, would centre on Queensland corruption leading up to the Fitzgerald Inquiry,[8]‘Fourth Series of Underbelly Series to Be Set in Queensland’, Herald Sun, 25 November 2009, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/television/fourth-series-of-underbelly-series-to-be-set-in-queensland/news-story/e87ae7dcca41babf9af8fdef5661e511>, accessed 25 February 2019. the eventual angle producers took was notably different, rewinding eight decades to the ‘razor gangs’ of the 1930s. For me, this is where the series begins to hit diminishing returns. Granted, the particulars are much the same – brawls, boobs and betrayals – but the core of cultural critique impelling the best episodes of the series thus far fades away for a return to empty, historically relevant thrills. While Underbelly continued to draw audiences, with Razor’s premiere the highest-rating TV drama episode in Australia for 2011,[9]See the entry for 2011 in Screen Australia, ‘Top 50 Episodes on Australian Free-to-air Television, 5-city-metro, 2008–2017’, ‘Top-rating Australian TV Drama – Metro & Regional’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/television/australian-content/top-drama-titles>, accessed 25 February 2019. the show’s cultural prominence was undeniably fading as its subject matter deviated from recognisable recent figures and headlines.

Digging into these television ratings helps us to understand the legacy of Underbelly. Granted, the series hasn’t disappeared entirely, as last year’s Chopper – with Vince Colosimo returning to the role of Alphonse Gangitano for the third time – attests, but it’s certainly not the juggernaut it once was. It’s also tempting to slot Underbelly into the continuum of crime dramas that have aired in Australia across the decades, as Andrew Nette did in his 2015 Metro piece ‘Crime Pays: Underbelly, Homicide and Blue Murder’.[10]Andrew Nette, ‘Crime Pays: Underbelly, Homicide and Blue Murder’, Metro, no. 183, Summer 2015, pp. 50–5. But, with only a passing interest in police-procedural conventions and an emphasis on crime over the investigation of the same, Underbelly feels like an outlier in this subgenre.[11]Interestingly, despite Underbelly’s success, there hasn’t really been an Australian series to follow directly in its footsteps in terms of exploiting the ‘true crime plus sex plus violence’ formula. The closest we’ve gotten is 2012’s Bikie Wars: Brothers in Arms, which I’d forgive you for forgetting. Rather, I’d argue that Underbelly’s legacy is found by checking the highest-rating Australian TV drama the year after Razor: the miniseries Howzat! Kerry Packer’s War. Or two years after that, when Underbelly spin-off Fat Tony & Co was outperformed by the miniseries Never Tear Us Apart: The Untold Story of INXS.[12]See the 2012 and 2014 figures, respectively, in Screen Australia, ‘Top 10 Titles on Free-to-air Television, 2008–2018’, ‘Top-rating First-release Australian Adult TV Drama’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/television/australian-content/top-drama-titles/first-release-series>, accessed 25 February 2019. Such ripped-from-the-headlines dramatisations[13]Though I don’t mean to contend that Underbelly inspired the production of such miniseries, which have dominated Australian scripted television over the past decade. For example, The King: The Story of Graham Kennedy (Matthew Saville, 2007) played on cable television a year before Underbelly and garnered significantly high TV ratings at the time. might diverge sharply from Underbelly’s subject matter, but each is intent on depicting episodes from Australia’s recent past with the same grit and glitz granted to American history in Hollywood films.

As evidenced by these ratings, this mode of storytelling clearly resonates with Australian audiences. This isn’t necessarily a surprise; true-crime and historical/biographical stories have always been broadly popular to a range of audience demographics both here and abroad.[14]See, respectively, Rob Owen, ‘True Crime Tales Are on the Rise Across Broadcast and Cable’, Variety, 3 August 2017, <https://variety.com/2017/tv/news/manhunt-unabomber-menendez-brothers-the-keepers-unsolved-1202510421/>; and Kat Eschner, ‘Why Do We Love Period Dramas So Much?’, Smithsonian.com, 15 December 2016, <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-we-love-period-drama-180961474/>, both accessed 27 February 2019. But Underbelly and the ‘Wikipedia’ miniseries that followed in its wake feel specifically geared to local audiences. That’s in part an obvious consequence of the subject matter; it’s hard to imagine international markets being especially interested in the crook culture of Kings Cross or the pitch that Samuel Johnson is Molly Meldrum.[15]Johnson was ‘hand-picked’ by Meldrum himself for the role; see Cameron Adams, ‘Samuel Johnson Transforms into Molly Meldrum for a New Miniseries’, News.com.au, 16 February 2015, <https://www.news.com.au/entertainment/tv/samuel-johnson-transforms-into-molly-meldrum-for-a-new-miniseries/news-story/7d08b01a7379e745d3bb5afd5793e7f4>, accessed 27 February 2019.

More significantly, the forthright mythmaking showcased in Underbelly and its ilk caters to a specifically Australian inclination to celebrate – or, at least, express fascination in – the dirtiest corners of our history. Whereas other nations’ most enduring historical icons might be war heroes or noble leaders, Australia’s is almost certainly Ned Kelly. An outlaw. A ‘rebel’. Remembered primarily for that fearsome suit of armour that’s indelibly associated with his inability to escape capture. His failure, in other words. As much as Australian myth does have a tinge of the jingoistic – cricketer Don Bradman’s intimidating batting ability, the so-called Anzac legend, platitudes about mateship – our ingrained tall poppy syndrome ensures that it’s the grimier legends that tend to take hold of the public imagination. Bob Hawke remains one of our most popular former politicians, not for any significant policy positions, but arguably for his ability to chug yard glasses (and, perhaps, his notorious infidelity) – which is why he gets to be played by Richard Roxburgh (in Emma Freeman’s Hawke, 2010) while Robert Menzies remains relegated to history textbooks.

Hollywood biopics may turn to hagiography more often than not, but Australian historical series, miniseries and films tend to centre on our crudeness, our corruption, our – if you’re being generous – ‘larrikin spirit’. The success of Underbelly can partly be credited to Aussie audiences’ desire to see our culture, even the seedy stuff, as significant. At the same time, it speaks to a roughness at the core of our character. Colonial Australia did, after all, begin with ships full of convicts; Underbelly reminds us that we haven’t necessarily travelled all that far.

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘Grave Doubts over Underbelly: Court’, The Age, 8 February 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/grave-doubts-over-underbelly-court-20080208-ge6pc2.html>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Nick Miller, ‘Pirates Promise Underbelly Downloads’, The Age, 13 February 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/technology/pirates-promise-underbelly-downloads-20080213-gds0uk.html>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 3 | A stuttering style of stop-motion most memorably used in Wong Kar Wai’s 1994 film Chungking Express, employed here for emphasis or to attempt to evoke excitement. |

| 4 | The first four seasons each had thirteen episodes, while seasons five and six as well as associated spin-off Fat Tony & Co had eight, eight and nine episodes, respectively. |

| 5 | Lauren Carroll Harris, ‘What Australian Screen Stories Get Wrong About Police, Crime and Brutality’, Daily Review, 1 December 2016, <https://dailyreview.com.au/australian-screen-stories-get-wrong-police-crime-brutality/53132/>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 6 | And every other kind of -phobic you could think of. Case in point: the death of The Golden Mile’s trans sex worker Wanda (Mitch Bartlett), who is treated with disdain by the officers who discover her body. |

| 7 | See Richard Clune & Yoni Bashan, ‘Underbelly Gangster Glamour Wears Off’, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 January 2010, <https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/underbelly-gangster-glamour-wears-off/news-story/7f39da23c8aa04c5c2d2a82fa80745e1>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 8 | ‘Fourth Series of Underbelly Series to Be Set in Queensland’, Herald Sun, 25 November 2009, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/television/fourth-series-of-underbelly-series-to-be-set-in-queensland/news-story/e87ae7dcca41babf9af8fdef5661e511>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 9 | See the entry for 2011 in Screen Australia, ‘Top 50 Episodes on Australian Free-to-air Television, 5-city-metro, 2008–2017’, ‘Top-rating Australian TV Drama – Metro & Regional’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/television/australian-content/top-drama-titles>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 10 | Andrew Nette, ‘Crime Pays: Underbelly, Homicide and Blue Murder’, Metro, no. 183, Summer 2015, pp. 50–5. |

| 11 | Interestingly, despite Underbelly’s success, there hasn’t really been an Australian series to follow directly in its footsteps in terms of exploiting the ‘true crime plus sex plus violence’ formula. The closest we’ve gotten is 2012’s Bikie Wars: Brothers in Arms, which I’d forgive you for forgetting. |

| 12 | See the 2012 and 2014 figures, respectively, in Screen Australia, ‘Top 10 Titles on Free-to-air Television, 2008–2018’, ‘Top-rating First-release Australian Adult TV Drama’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/television/australian-content/top-drama-titles/first-release-series>, accessed 25 February 2019. |

| 13 | Though I don’t mean to contend that Underbelly inspired the production of such miniseries, which have dominated Australian scripted television over the past decade. For example, The King: The Story of Graham Kennedy (Matthew Saville, 2007) played on cable television a year before Underbelly and garnered significantly high TV ratings at the time. |

| 14 | See, respectively, Rob Owen, ‘True Crime Tales Are on the Rise Across Broadcast and Cable’, Variety, 3 August 2017, <https://variety.com/2017/tv/news/manhunt-unabomber-menendez-brothers-the-keepers-unsolved-1202510421/>; and Kat Eschner, ‘Why Do We Love Period Dramas So Much?’, Smithsonian.com, 15 December 2016, <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-we-love-period-drama-180961474/>, both accessed 27 February 2019. |

| 15 | Johnson was ‘hand-picked’ by Meldrum himself for the role; see Cameron Adams, ‘Samuel Johnson Transforms into Molly Meldrum for a New Miniseries’, News.com.au, 16 February 2015, <https://www.news.com.au/entertainment/tv/samuel-johnson-transforms-into-molly-meldrum-for-a-new-miniseries/news-story/7d08b01a7379e745d3bb5afd5793e7f4>, accessed 27 February 2019. |