THE NFSA RESTORES COLLECTION: PART 54

My interest is in human behaviour and the representation of the human spirit and what it means to be alive.

– Lawrence Johnston[1]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Dreaming in Motion: Celebrating Australia’s Indigenous Filmmakers, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 2007, p. 40, available at <https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Dreaming-in-Motion.pdf>, accessed 30 August 2021

When it was released in 1994, Lawrence Johnston’s poetic documentary Eternity hit a sweet spot within the Australian as well as international festival landscape: it was ambitious in conception, a cinematic work adopting a formalist approach that foregrounded representation, aesthetic choices, and a notable documentary voice.[2]For more on the notion of documentary voice, see Bill Nichols, ‘The Voice of Documentary’, Film Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, Spring 1983, pp. 17–30. Johnston combined found footage, film noir–style re-creations, talking-head interviews, distinctive editing and an evocative orchestral soundtrack to present a unique and unexpected version of the history he was recounting. He had been captivated by the mythology that had formed around Arthur Stace, a man who wrote the word ‘Eternity’ in chalk on the footpaths of Sydney for decades until his death in 1967.

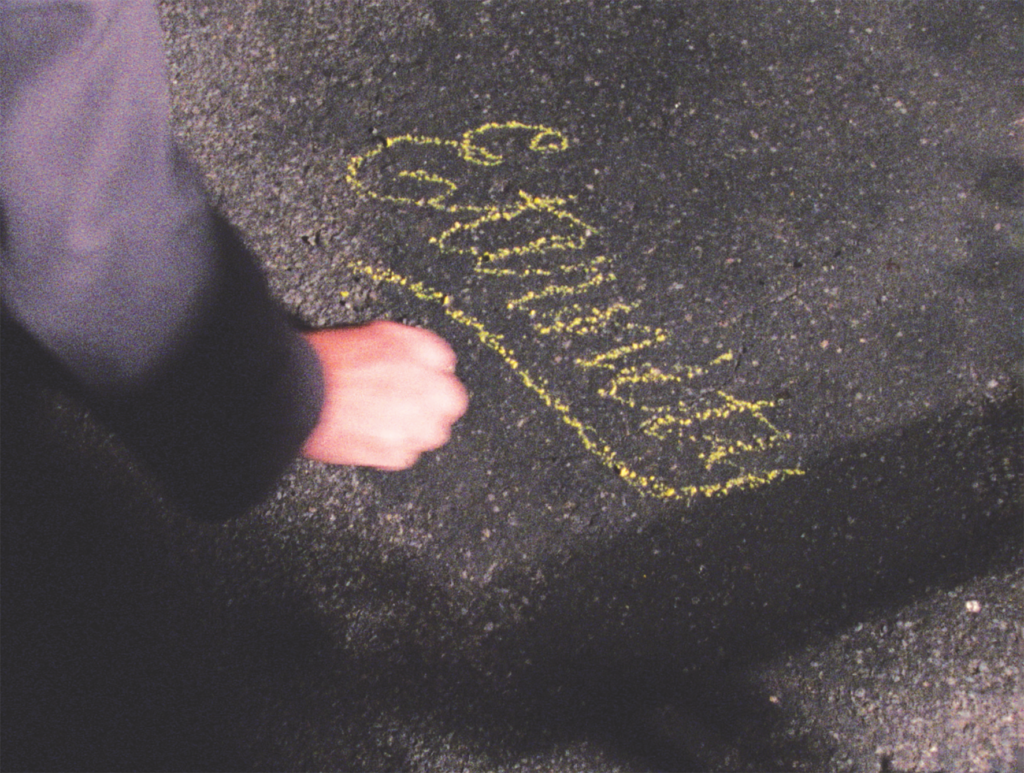

The legend of ‘Mr Eternity’ had grown out of the longevity of Stace’s self-imposed mission, his capacity to do his work without being noticed, and the beautiful and distinctive way the single word was written each time, in what interviewee Dorothy Hewett describes in the film as ‘perfect copperplate script’. Johnston’s film communicates fascination with such a modest endeavour becoming part of the mythos of Sydney, a city typically associated with earthly pleasures. Eternity also foregrounds individual experience through its inclusion of a wide range of personal testimonies from interviewees, an eclectic assemblage of ‘witnesses’ who reveal the different ways in which a significant collective memory can be inflected and construed. The poetic impact of Eternity relates to its contrapuntal representation of the alternative – ‘other’ – Sydney through which Stace moved, alongside individual stories and recollections that attest to the power of the personal.

In 2019, the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) completed a restoration and digitisation of Eternity as part of the NFSA Restores program, offering audiences the opportunity to revisit the film or see it for the first time. The subsequent premiere of the restored version of the film at the Sydney Film Festival that June marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of its initial release. Commenting prior to a Melbourne screening of the restored film, Johnston remarked, ‘One of our aims was to make a film that whenever you watched it, you weren’t really quite sure when it was made in time.’[3]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in David Tiley, ‘Eternity 24 Times a Second to Stop the Passage of Time’, Screenhub, 9 October 2019, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2019/10/09/eternity-24-times-a-second-to-stop-the-passage-of-time-258974/>, accessed 30 August 2021. Accordingly, intersecting with memory and myth, Eternity weaves its narrative out of patterns of experience, held together by the chronology of Stace’s life story. While this evocative approach to the past does indeed give Eternity a timeless quality, the film itself is very much part of history – a history that includes the climactic lighting up of the Sydney Harbour Bridge with a replica of Stace’s distinctive insignia during the fireworks display that ushered in the new millennium. In this context, Johnston’s rhythmical repetition of shots featuring the Harbour Bridge has a kind of ghostly prescience.

Johnston’s aesthetic choices in Eternity connect with themes relating to identity, place and purpose. He has described himself as a humanist, a quality that is revealed in the film through the chorus of individual voices connected by a shared desire to find meaning in Stace’s endeavour and that draw on the collaborative dimension of documentary.[4]For a thoughtful discussion on collaborative documentary, see Leah Anderst, ‘Memory’s Chorus: Stories We Tell and Sarah Polley’s Theory of Autobiography’, Senses of Cinema, issue 69, December 2013, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/memorys-chorus-stories-we-tell-and-sarah-polleys-theory-of-autobiography>, accessed 11 July 2021. For Stace, the decades-long project was an evangelical mission relating to his own spiritual and personal redemption from alcoholic social outcast to teetotal Christian proselytiser. As unexpected as it might initially seem that Johnston – a gay man, the co-founder of the Melbourne Queer Film Festival and a non-Christian – should be drawn to such a story, he related to Stace as a fellow outsider and non-conformist:

I’m not a Christian person myself, so I don’t think [it’s] great that he was pushing the word of God, because that can be incredibly conservative and oppressive. His behavior – what he did – and the way it affected people by seeing it, and the way they interpreted it – to me that’s the beauty of the story.[5]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Pauline Adamek, ‘Eternity – A Filmic Tribute to a Sydney Ghost by Lawrence Johnston’, ArtsBeatLA, 20 January 2013, <http://www.artsbeatla.com/2013/01/eternity/>, accessed 11 July 2021.

Johnston had initially discovered the story when he saw a picture of Stace in a catalogue produced for the REMO General Store in Sydney and found himself captivated by the image’s Diane Arbus–like strangeness. This photograph, taken by The Sydney Morning Herald’s Trevor Dallen in 1963, was referencing a commercial collaboration between pop artist Martin Sharp and retail entrepreneur Remo Giuffré that drew on Sharp’s ‘Eternity’ project to create merchandise (including limited-edition prints, hats and T-shirts).[6]See Remo Giuffré, ‘Eternity’, REMO General Store website, 21 July 2020, <https://remogeneralstore.com/blogs/news/eternity>, accessed 11 July 2021. In the mural Sharp created as part of the REMO collaboration, he reproduced a version of Stace’s insignia in canary yellow on a vivid blue background. Because Johnston arrived at his documentary subject by way of Sharp and the REMO General Store, he began the project with a perception of Stace’s ‘Eternity’ as a floating signifier, absorbing preferred or invested meanings that would reveal a range of personal and shared dreams and desires.

Production, promotion and reception

Eternity was Johnston’s second film, following on from the mid-length dramatic feature Night Out (1990), his Swinburne Film and Television School graduation work, which was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival. However, when producer Susan MacKinnon pitched Eternity to the ABC, Johnston’s Cannes credentials didn’t garner a presale; the response she received, she recounts, was that ‘the story was a beautiful script, but the subject matter was too marginal’.[7]Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Pamela Beere Briggs, ‘Talking Heads: Eternity’s Lawrence Johnston and Susan MacKinnon’, International Documentary, vol. 14, no. 1, February 1995, available at <https://www.documentary.org/feature/talking-heads-eternitys-lawrence-johnston-and-susan-mackinnon>, accessed 2 September 2021. The marginal nature of the narrative subject was the essence of the story, however, and it was the artistry of Johnston’s creative perspective that made MacKinnon so passionate about the project. (‘Eternity particularly made me feel that film was an art-form [… and] not fodder for television stations,’ she later recalled.[8]Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Trish FitzSimons, Pat Laughren & Dugald Williamson, Australian Documentary: History, Practices and Genres, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011, p. 101.) Johnston’s vision and poetic approach held more sway with the Australian Film Commission (AFC), which, under the aegis of director of film development Peter Sainsbury, was seeking at this time to support documentaries that promised ‘radical aesthetic achievement’.[9]Peter Sainsbury, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., p. 134. Film Victoria had already provided Johnston with A$20,000 in research funding; MacKinnon states that, by the time she was seeking finance for its production, ‘Lawrence had written a full-length script [that was] very close to how the film ended up.’[10]MacKinnon, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., p. 101. As Tim Read – a successor of Sainsbury’s in the commission’s film-development role – relates, the effect of AFC funding priorities at this time was that ‘different kinds of documentaries stood a chance of receiving investment finance, without editorial or programming philosophy to guide decisions’.[11]Tim Read, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., pp. 134–5. The Eternity production received A$300,000 in finance from the AFC and a A$20,000 top-up from the New South Wales Film Commission. In a 1995 interview published in the US magazine International Documentary, Johnston highlighted how this form of public support liberated the project from the time-consuming pressure faced by independent documentarians in the United States of having to finance their projects through private sponsorship.[12]Briggs, op. cit.

Eternity premiered at the Sydney Film Festival in 1994, and subsequently received a limited theatrical release in Australia through Ronin Films. MacKinnon was determined to gain as much traction for the film as possible, and launched an energetic marketing campaign. Sydney was the epicentre of all this activity, which included a team of volunteers using stencils to chalk the word ‘Eternity’ on Sydney footpaths during the night as well as a window display for the film at the REMO Department Store.[13]FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, op. cit., p. 101. Those who saw the film in Sydney at the Academy Twin would have also encountered Sharp’s mural, which was ‘hauled in and installed’ for the duration of its four-week season.[14]David Tiley, ‘Long Tail: An Object Lesson in the Reach for Eternal Sales’, Screenhub, 25 July 2014, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2014/07/25/long-tail-an-object-lesson-in-the-reach-for-eternal-sales-244946/>, accessed 2 September 2021. Reviewers responded to the enigmatic portrayal of the film’s subject and its poetic resonance;[15]Barbara Creed, ‘Ghost Who Walked the City Streets’, The Age, 23 March 1995, p. 20. for instance, then-president of the Film Critics Circle of Australia Peter Crayford deemed it ‘one of the best Australian films of any length made in 1994’ in a piece for The Australian Financial Review.[16]Peter Crayford, ‘Shorts Long on Variety’, The Australian Financial Review, 16 June 1995, p. 18.

Despite MacKinnon’s valiant effort to build a commercial audience for Eternity, a 56-minute poetic documentary was never going to have the critical attention or popularity won that year by the dazzling dramatic features The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) and Muriel’s Wedding (PJ Hogan, 1994). On the festival circuit, however, it achieved outstanding success. Not only was Eternity screened at more than sixty film festivals, but it also won a slew of awards both in Australia and internationally, including the Silver Hugo for Best Documentary at the 1994 Chicago International Film Festival and the nod for Best Achievement in Cinematography in a Non-Feature Film at the 1994 Australian Film Institute Awards. Its screening at the Toronto International Film Festival generated some screenings in the US, including a four-month season at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.[17]See Tiley, ‘Long Tail’, op. cit. Much to MacKinnon’s satisfaction, she was able to secure a A$25,000 licence fee from the ABC as a result of Eternity’s creative and critical success. In the long term, much of its viewership came from DVD sales; MacKinnon notes that the film has had ‘a significant life with religious audiences’, as well as solid sales to university and school libraries in Australia and New Zealand.[18]Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Tiley, ibid. In choosing to restore and digitise Eternity as part of its NFSA Restores program, the NFSA emphasised that it could now ‘be seen on the big screen in today’s digital cinemas’.[19]Chris Arneil, ‘New Restoration Premieres at Sydney Film Festival’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 7 June 2019, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/nfsa-restores-eternity-premiere-sydney-film-festival>, accessed 11 July 2021. Importantly, during an era of constant change and obsolescence, the film’s selection for restoration, digitisation and preservation by the NFSA is an acknowledgement of its cultural importance and ongoing place in Australian screen culture and history.

Locating meaning

Watching the film decades after its initial release highlights the way that it speaks to the present as an ongoing story, due to the purity of its articulation of human experience and the search for meaning. One of the outstanding aspects of Johnston’s representation of this search in terms of both individual and collective identities is his complete lack of judgement. Ironically, in his 2017 book Mr Eternity: The Story of Arthur Stace, Roy Williams rues the ‘ambivalence’ Johnston reveals in interviews about his subject’s religious message.[20]Roy Williams with Elizabeth Meyers, Mr Eternity: The Story of Arthur Stace, Acorn Press, Sydney, 2017. But the beauty of the way that the individual voices and testimonies are woven into the fabric of the film is that each is given a space and a place in Johnston’s exploration of purpose and identity, including those who perceive Stace’s work through the lens of faith.

The beauty of the way that the individual voices and testimonies are woven into the fabric of the film is that each is given a space and a place in Johnston’s exploration of purpose and identity.

As a beneficiary of the AFC’s ‘unhindered support for the director’s voice’,[21]FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, op. cit., p. 135. Johnston was able to pursue his conception of Eternity as a poetic documentary with a dreamlike sense of place, impressionistic editing, atmospheric music and film noir aesthetic. In his approach to his subject, Johnston is on the side of documentary filmmakers who, in the words of director Werner Herzog’s Minnesota Declaration, pursue an illuminating truth ‘through fabrication and imagination and stylization’ rather than adhering to ‘the truth of accountants’.[22]Werner Herzog, ‘Minnesota Declaration’, 30 April 1999, available at <https://www.wernerherzog.com/complete-works-text.html#2>, accessed 11 July 2021. In documenting Stace’s ‘extraordinary story’,[23]‘It’s not an ordinary story, and I think that’s the reason people go to see movies: […] to see extraordinary stories.’ Lawrence Johnston, in ‘Eternity: Lawrence Johnston Interview’, The Movie Show, 1994, available at <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/11676227585/eternity-lawrence-johnston-interview>, accessed 11 July 2021. Johnston had no interest in realism, and the wealth of archival footage that he accessed is incorporated into the narrative in surprising ways; as the director puts it, ‘It was always meant to be a cinematic documentary, rather than a realist one. If we had made a real documentary out of it, it would have lost the magic.’[24]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit. In this way, Eternity brings to mind Bill Nichols’ classic articulation of the documentary voice through which the filmmaker makes visible a documentary text’s ‘epistemological and aesthetic assumptions’ and its nature as discourse ‘through [its] very tissue and texture’.[25]Nichols, op. cit., p. 18. However, whereas Nichols suggests the documentary voice can be compromised by a non-hierarchical approach to the truth value granted to interviews and interviewees, in Eternity, the truth does indeed lie in the voice of every interviewee, with each separate and individual voice woven into the tissue and texture of Johnston’s documentary narrative.

A distinctive element of the experience of watching Eternity is the authenticity granted to each of the witnesses. There are two distinctive threads: one made up of those who ‘read’ Stace’s evangelical mission ‘with the grain’; and the other, of those who interpret the ‘Eternity’ message in individual terms, more or less against the grain. Within the documentary, these voices and testimonies are given equal weight: the declamatory certainty of Ruth Ridley (daughter of evangelist John, whose sermon ‘Echoes of Eternity’[26]An audio recording of John Ridley’s sermon can be downloaded from SermonIndex.net at <https://www.sermonindex.net/modules/mydownloads/viewcat.php?cid=629>, accessed 11 July 2021. inspired Stace to begin what would become his life’s work) that he was an instrument of God;[27]She describes Stace’s ‘Eternity’ as ‘a sermon he was writing in the streets’. painter and filmmaker George Gittoes’ intimate memory of an encounter with him and its significance in his own life and art; poet and novelist Hewett’s writerly perception of him as a Sydney identity; Dallen’s down-to-earth account of taking the iconic photograph of him; and the recollections of Australian Red Cross volunteers Shirley Wood and Helen Livingstone about their time working with him at the charitable organisation. As Stace moves through the film like a ghost, his written word is brought to life through the witnesses. Their perception of who he was and what his work means to them reveals a vivid sense of who these people are and how each perceives their own life and place in the world. As they are offered, the witnesses’ testimonies come together to create a kind of medley, with each unique perspective revealing how people create personal meaning out of shared stories and demonstrating how – as the director has described it – ‘Stace’s work tied a city together in a common experience’.[28]Greg Burchall, ‘Film Portrait of Mysterious Evangelist Night Writer’, The Age, 4 April 1995, p. 20.

Urban canvas

Johnston begins Eternity with a montage of mid-twentieth-century archival footage of well-known international landmarks and locales – the Empire State Building, Times Square, Trafalgar Square, the Eiffel Tower, Parisian cafes, Hollywood Boulevard and the Sydney Harbour Bridge – separated by a swinging pendulum. The director explains the purpose of the sequence thus:

It was to set up that there are icons in our lives that bring us together in common experience and it’s those commonalities that make us connect with one another. ‘Eternity’ was an icon in this city, Sydney, for forty years.[29]Johnston, quoted in Adamek, op. cit.

This brief opening montage is also replete with the signs that are such a feature of urban landscapes; in their similarity to and difference from Stace’s chalked sign, they highlight the tension in the film around the search for identity and purpose through either the lived experience of the city or the pursuit of eternal life. The intercontinental expansiveness of the opening is reoriented by a series of extreme close-up shots of a dictionary entry for the word ‘eternity’. White against a black background like Stace’s white chalked word on asphalt, the fragments of incomplete words and definitions introduce themes of mortality and eternal life, while also heralding the disruptive formal choices Johnston and cinematographer Dion Beebe make in framing the re-created scenes of Arthur Stace (as played by Les Foxcroft) walking through the streets of Sydney. Familiar places are made unfamiliar, unsettling and disorienting to the viewer – a world made strange. Shooting on 16mm film, Beebe transformed these dramatised scenes into the haunting images envisaged by Johnston, who recalls telling the cinematographer that he ‘wanted the Arthur Stace figure to walk through the film like a ghost, just as he had walked through the lives of the people in Sydney’.[30]Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit.

Johnston has described the influence of his formative love of Hollywood films on his approach to filmmaking, and in Eternity the film noir aesthetic is a key aspect of his address to the audience.[31]John Hughes, ‘Life or the Transience of Existence: Director Lawrence Johnston Interviewed by John Hughes’, Cinema Papers, no. 112, October 1996, p. 9. Dark shadows and silhouettes, evocative lighting and disjunctive camera angles, anonymous urban nightscapes and fragmented bodies take the narrative beyond history. Johnston explains that this otherworldliness was central to his conception of Eternity as an immersive cinematic documentary – one that would eschew the realism associated with television documentaries:

When you go into the film, it’s a dark kind of world, and you’re submerged into it. Dion Beebe and I planned the way the film would look so that it would be seen on a larger screen in the dark.[32]Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit.

Through Stace’s haunting presence and journey across time and space, as critic Pamela Beere Briggs has put it, ‘the viewer becomes a witness and a participant in shared memory’,[33]Briggs, ibid. and is engaged in a process of personal and existential reflection similar to that demonstrated by the interviewees. In turn, the viewer is positioned within the extended conversation formed out of the recollections and meanings drawn from and imposed upon Stace’s project.

Ross Edwards’ symphony Da Pacem Domine is a dominant element in the soundscape and integral to the elegiac mood of the narrative. It functions as a sonic representation and accompaniment to Stace’s haunting presence, and communicates a similar unsettling tone of displacement. The ominous notes of the symphony not only suggest Stace’s resolute commitment to his journey, but also the relentless passage of time, a sombre reminder of mortality that is echoed in the tolling of the bell in the GPO clock tower. Two other pieces of music are also featured: a burst of the African-American spiritual ‘Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho’ accompanying the bright lights of pagan Kings Cross; and Albert Hay Malotte’s arrangement of ‘The Lord’s Prayer’,which accompanies Stace’s conversion and is reprised at the end of the film. The final moments of Eternity take the form of a defamiliarising coda in which the transcendent magnificence of Malotte’s work is undercut by a disjunctive montage of rapid cuts and flashes of light that fragments and disembodies Stace’s figure. At this final stage of the narrative, Stace’s passage through the world of the film loses its structuring purpose of drawing together the layers of collective and individual memory, and the symbolic persona that has been constructed around his story breaks apart. The montage evokes a barrage of camera flashes, a metaphor that picks up on the motif of film and photography that punctuates the narrative, and suggests an analogy between photography’s impossible desire to resist the march of time by ‘capturing’ life and the search for the man at the film’s centre.[34]Roland Barthes describes the photograph as ‘a figuration of the motionless and made-up face through which we see the dead’. Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Cape, London, 1982, p. 32.

Rather than an eclectic patchwork, the film is structured more as a poetic tapestry representing the connections between people’s diverse experiences.

Up until this dramatic disjuncture, the dramatised scenes of Stace’s life journey are a distinctive, expressionistic, at times surreal narrative and visual strand holding together the biographical collage that surrounds it. This collage combines recorded witness interviews, expressive composed shots, still images and archival footage that is at times thematic, illustrative or dramatically evocative, such as the shot from Painted Daughters (F Stuart Whyte, 1925) of pigeons fluttering as a man emerges from a bar doorway.[35]Briggs, op. cit. Rather than an eclectic patchwork, the film is structured more as a poetic tapestry representing the connections between people’s diverse experiences. The extensive use of dissolves expresses this continuity both within and across time, as does the use of split edits and voiceover in the sound design.

Speaking in tongues

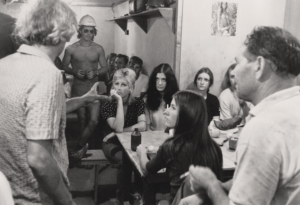

The witness interviews are central to Eternity’s poetic documentary style, to Johnston’s wider exploration of shared and individual memory, and to the humanism that drives his work as a whole. They are shot in colour to communicate a sense of the present and of lives being lived, and contrast with the eeriness of the black-and-white, shadow-filled mise en scène dominating the film’s depiction of the past. In her 1995 review of Eternity, written during its short season at the George Cinemas in Melbourne, Barbara Creed suggests that the interviews can ‘seem oddly out of place’ in a ‘documentary that generally shuns realism’.[36]Creed, op. cit. Yet Johnston – with some exceptions – eschews the naturalism that conventionally communicates documentary authenticity, instead composing, lighting and shooting these interviews to imbue them with a vintage quality that highlights their connection to the past through the process of remembering. In sharing their memories and experience of Stace and his ‘Eternity’ project, the witnesses reveal as much about themselves as they do about the object of their accounts. When describing the people he interviewed for his later documentary Neon (2015), Johnston highlighted the importance of personality in the interviewed subject: ‘It’s like an actor; they’re giving a performance in a sense.’[37]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Tracey Korsten, ‘Feeling the Glow: Lawrence Johnston’s Neon’, Glam Adelaide, 24 August 2016, <https://glamadelaide.com.au/feeling-the-glow-lawrence-johnstons-neon/>, accessed 11 July 2021. And in Eternity, the individuality of each witness is integral to the film’s exploration of Stace’s life story, with their shared presence contrasting with his shadowy identity. The way these testimonies are staged and woven into the overall visual landscape of the film contributes to Johnston’s thesis about the meanings that have accrued around Stace’s work and the interconnection between individual and collective memories and identities.

With a couple of exceptions, each witness is positioned in front of a rear projection. This backdrop may or may not communicate something significant about who they are and the story they are telling, and contrasts with the recurring shot of the silhouetted figure of Foxcroft’s Stace in front of a blank screen. The staging of the witness testimonies creates an uncanny decoupage-like border around the person speaking, while the gentle shadow cast by the warm key light adds a theatrical quality (poet Robyn Ravlich is one of the few interviewees who is not shot in front of a projected background, her interview instead being lit with the natural light coming in from a window). Because we are expecting to be able to interpret what these people mean within the larger story that Johnston is telling about memory and identity, the naturalistic style of Ravlich’s presentation is full of meaning and asks to be interpreted in the same way as the stagy artifice of the other interviews. Is the more conventional documentary style with which her interview is filmed aligned with the gravity of her persona? Is it communicating that she is not actually a witness, as the producer of The Eternity Enigma, a 1992 ABC radio documentary about Stace?[38]A recording of Ravlich’s program is available at <http://mpegmedia.abc.net.au/innovation/sidetracks/sydney_content/mp3/eternity/eternity_mobile.mp3>, accessed 5 September 2021. Ravlich’s positioning in Eternity seems to suggest an alternative mode of documentary practice, a reflective approach to the evidence that yields illuminating insight but should not be mistaken for the full story. Instead, Ravlich’s perceptive observations are incorporated into the medley of voices and testimonies activated by the ‘Eternity’ mythology.

While Johnston’s non-hierarchical approach and activation of the witnesses’ separate accounts have been situated above in the collective terms of the medley – where each individual contribution becomes part of the whole – groups of individual voices could also be said to work together in harmony. This is most obvious in the case of Stace’s Christian friends and acquaintances, but equally relates to the representation of bohemian Sydney. The staging of the Christian witnesses, all of whom knew Stace personally, is made distinctive through the Romantic picturesque style of the background images projected behind them. The arrangement and composition of the interviewed subjects in front of these backdrops brings to mind both the symbolic codes of classic portraiture and the kitsch scenic backgrounds favoured by photographers in the first half of the twentieth century. Ruth Ridley’s compelling testimony, which might best be described as an oration, is delivered in front of an image of a blue-tinted moonlit seascape of jagged rocks and ominous dark clouds. Other Christian friends and acquaintances – Wood, Reverend Bernard Judd, Reverend George Rees, Rex Beaver and May Thompson – are also placed against backgrounds that draw on the awe-inspiring beauty of nature. This picturesque imagery reaches its apotheosis in Paddy Newnham’s account of Stace’s death, where the raging rock-strewn torrent projected behind him dissolves into an image of a storm-tossed ocean. The camera rises upwards to reveal a sky above illuminated by a cross adorned with a crown of thorns. Johnston has commented that viewers of Eternity mistakenly perceive him to be religious, and it is not difficult to see how the imagery he chooses in these sequences could lead to this assumption. Instead, the crucifixes, statuary and exalted religious symbolism connect with Johnston’s exploration of the influence of faith on memory and experience, and are evidence of his openness to the different ways that people bring meaning to their lives, particularly through their memories of the past.

Another grouping is formed out of those whom Stace influenced creatively: Gittoes, Sharp, Hewett, actor Colin Anderson and architect Ridley Smith. With the exception of Hewett, the artists are posed in front of an identifying back projection in the same way as Stace’s friends and acquaintances, but without the latter grouping’s stylistically similar imagery. This second group instead foregrounds Stace’s unwitting place in a tradition of Sydney art making, and the staging of their testimonies reflects the range of meanings engendered by individual interpretations of a shared myth, one that may or may not be based on religious faith. Gittoes and Sharp are interviewed in front of their celebrated artworks inspired by Stace; Smith is framed by James Cant’s The Bridge, a 1945 modernist painting featuring the Harbour Bridge; and Anderson, remembered for singing the ‘Eternity’ song at a university revue, is posed against an impressionistic image of Stace’s legendary insignia.

Hewett pairs with Ravlich in being the only other witness without an identity-building back projection; but in contrast to the utilitarian set-up of Ravlich’s interview, her vivid red dress against the purple velvet of an antique chaise longue strikes a theatrical note. She recounts how the experience of encountering the word ‘Eternity’ – its white letters written on a black surface, she says, were like receiving a message from outer space – and then later finding out about its writer inspired an episode in her debut novel Bobbin Up. As she reads the passage from her book about ‘a little man in a stiff, starched collar and a high-crowned felt hat’ who squats down to write the word in ‘perfect copperplate’, the episode is re-created visually and incorporated into the expressionistic visual aesthetic of the Eternity narrative as a whole. The dramatisation of Hewett’s work is a vivid example of how the interviewees’ memories are woven into the fabric of the film, dissolving the border between their past experiences and the film narrative, as well as between the individual meanings and identities that are brought together through the mythology accrued by a single inscribed word.

The power of Stace’s decades-long journey through the streets of Sydney and beyond relates to the purity of the message he shared and his purposeful commitment to his sacred mission. The weight of meaning this single word bears is at the heart of its significance, and leads Sharp and Gittoes in particular to connect with Stace as a fellow artist. For Sharp, Stace’s work based on a single word is comparable to Patrick White’s novels, and encountering it ‘made walls disappear’. In a similar vein, Gittoes reflects that, in his encounter with Stace as a ‘fifteen-year-old boy looking for signs’, ‘the one word seemed to be a whole book of words’. His expressive account of seeing Stace reflected in glass is replete with detail and significance, in the way that a memory can become part of a person’s identity through being honed and polished over time.

The word made manifest

The turning point within the Eternity narrative, Stace’s embrace of John Ridley’s sermon as a message to him from God, leads into a fugue-like sequence in which extreme close-ups of ‘Eternity’ being chalked on the ground interconnect with witnesses’ recollections of their experience of encountering the inscription on the streets of Sydney. The slow and rhythmical movements of the disembodied hand holding the chalk are accompanied by the rasping sound of chalk on hard paving and the choral majesty of Malotte’s ‘Lord’s Prayer’, an aural contrast that draws attention to the earthbound simplicity of Stace’s project and its sacred purpose. As the witnesses attest to the impact and mystery of ‘Eternity’, much is made of the miracle of the actual writing of the word, with Stace having been instantly and wondrously invested with the ability to not only write his inscription in ‘perfect copperplate’, but also subsequently reproduce the same perfection up to half-a-million times over nearly four decades. Integral to Johnston’s film is the power of the word in place, and the mystery and impact of its appearance. Religion becomes folklore through the visual repetition of the moment of writing, the sound of chalk on the ground and the layering of voices describing a shared experience emerging from a magical space in the city.

Eternity is a film about Sydney. It is an exploration of the meaning that a city accrues over time and the myths that emerge as part of a shared history. Sharp positions Stace’s ‘Eternity’ as ‘belong[ing] to the language of Sydney’, and Hewett describes Stace himself as being part of the fabric and identity of a city characterised by its eccentrics. While various witness accounts describe the breadth of Stace’s work – which stretched across Sydney, out into the suburbs and eventually to other towns – his journey is depicted as an urban one, connected with the built environment of the inner city. Anderson, who grew up in Newcastle, recalls being captivated by the idea of Stace’s ‘Eternity’ as synonymous with the exotic nature of the cosmopolitan city, while Ravlich’s upbringing in the country left her completely unprepared for the transgressive possibility that someone might write on the built environment (photojournalist Mark Balfour refers to Stace as Australia’s first graffiti artist, a description that has now become part of the ‘Eternity’ story). The version of Sydney communicated through the film noir aesthetic is a place of dark shadows, ominous silhouetted shapes, and extreme camera angles and perspectives. Sydney – known for being, as Johnston puts it, ‘very glitzy, and modern’[39]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Sarah Swain, ‘Exclusive: Legendary Sydney Figure “Mr Eternity” Brought Back to Life’, 9News, 11 June 2019, <https://www.9news.com.au/national/sydney-film-festival-mr-eternity-arthur-stace-film/7abef3eb-11c2-4d44-bcbf-15d2e30aee8c>, accessed 11 July 2021. – becomes its shadow self, a place of ‘memory and meaning and mortality’.[40]Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Burchall, op. cit. The gravity of the soundtrack builds on this sense of a city that wears its past heavily. Johnston found it fascinating that Stace’s conversion occurred at the same time as the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, perceiving the coincidence as a coming together of two icons of the city. In Eternity’s opening montage, the bridge is presented in colour as an emblem of the city; when it next appears, it has been incorporated into the sombre black-and-white mise en scène of Stace’s dramatised life story, looming in the background as he heads into the future as a redeemed man; in a subsequent scene, it becomes a surface to be written on; and it figures once more in the bleak sequence set on Observatory Hill in which he contemplates the urban landscape after the death of his wife. For the Christian witnesses, the city is a halfway house on the way to eternal life; for others, such as Ravlich, the city itself is a place of eternal life, built out of lived experience and the stories and mythologies that emerge in its wake.

For the Christian witnesses, the city is a halfway house on the way to eternal life; for others, such as Ravlich, the city itself is a place of eternal life, built out of lived experience and the stories and mythologies that emerge in its wake.

One of the most vivid histories to emerge in the film is the tale of the bell in the GPO clock tower. A man by the name of Sydney Davies approached Johnston with a story from his time as a quantity surveyor for a company working on the rebuilding of the structure. The project had reached the point at which the huge hour bell had been lifted into the tower, and, on the following day, workers discovered the word ‘Eternity’ inscribed on the inside of the bell in Stace’s familiar handwriting. As Davies relates the story in the film, he enacts Johnston’s conceit that interviewees are witnesses providing testimony: through his careful choice of words, dramatic timing, general air of gravity and weighting of each detail, he is providing an important piece of evidence to support the mythology that has grown up around Stace. Of the discovery of the word chalked inside the bell, Davies attests, ‘I have no hesitation to fix it to the man who wrote “Eternity” over every footpath everywhere in Sydney.’ Many of the witnesses who are interviewed in Johnston’s film had already contributed to Ravlich’s radio documentary a few years earlier, but this was a new story that emerged when Johnston was researching the film, and the revelation that the chalked inscription was still there thirty years later is a moment of great significance in the film.[41]Briggs, op. cit. Davies’ story forges a powerful connection with Johnston’s use of the tolling of the bell as a metaphor for mortality. At the same time, the discovery that Stace’s insignia can still be found in the bell long after his death builds on the idea of the city’s connection to eternity through the lives that have passed through it and the stories it has accrued over time.

Ghosts of Sydney

While Johnston has pointed to the haunting image of Stace that he stumbled upon in the REMO catalogue as his initial inspiration for the film, a deeper motivation was grief. In interviews following Eternity’s release, Johnston has described how his growing awareness of the impermanence of human existence influenced the film; he has spoken of the loss of close friends through AIDS,[42]ibid. to whom the film is dedicated (together with his Swinburne Film and Television School mentor Brian Robinson, who had recently died of a heart attack).[43]Burchall, op. cit. Despite his thesis that the city is a kind of eternity, Johnston has created Sydney as a liminal space, using the visual language of film noir to suggest Stace’s continued haunting presence as a signifier of mortality, as well as conveying the threat and promise that the single word ‘eternity’ carries with it. The city to which Stace lays claim is monumental and impersonal, a noplace that exists outside of time and offers little trace of human life. The sombre notes of Edwards’ symphony, which was written as a threnody – or lament – for his terminally ill friend Stuart Challender, build on the film’s theme of haunting, loss and mortality.[44]See ‘Ross Edwards: Symphony no. 1 Da Pacem Domine (1991)’, ABC Classic, 14 December 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/classic/read-and-watch/classic-australia/ross-edwards-symphony-no-1-1991/10619828>, accessed 11 July 2021.

In presenting the shadow side of Sydney, one that carries with it the complex history of the diverse lives that have been lived there over time, Johnston engages with the uncanny: the familiar made unfamiliar. Much as film noir, in the tradition of urban gothic, builds the fear of the unknown into the city, the recognisable and familiar becomes shadowy and uncertain in his film. As Stace makes his way across the haunted cityscape of Sydney inscribing it with his one-word sermon, this process of writing and inscription bears with it a history of colonisation and dispossession. Ravlich describes Stace’s project as a ‘marking out of territory’ in the form of ‘a white Christian songline’, a description that draws attention to the way each of the witnesses draws meaning from Stace’s project as a way of marking out their own territory and place in the world. Johnston is a man who likes signs – so much so that he later made an entire film about them, Neon – but his interest is in the significance they accrue and what they communicate about people’s connection to place. Eternity is a palimpsest, writing layers of evocation and interpretation over the meaning, influence and affect of Stace’s ‘Eternity’. If the eternity of the city is one based on history, human experience and memory, then there are many other voices to be heard, and many other stories to be told.

Select bibliography

‘Eternity: Lawrence Johnston Interview’, The Movie Show, 1994, available at <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/11676227585/eternity-lawrence-johnston-interview>.

Pauline Adamek, ‘Eternity – A Filmic Tribute to a Sydney Ghost by Lawrence Johnston’, ArtsBeatLA, 20 January 2013, <http://www.artsbeatla.com/2013/01/eternity/>.

Chris Arneil, ‘New Restoration Premieres at Sydney Film Festival’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 7 June 2019, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/nfsa-restores-eternity-premiere-sydney-film-festival>.

Pamela Beere Briggs, ‘Talking Heads: Eternity’s Lawrence Johnston and Susan MacKinnon’, International Documentary, vol. 14, no. 1, February 1995, available at <https://www.documentary.org/feature/talking-heads-eternitys-lawrence-johnston-and-susan-mackinnon>.

Greg Burchall, ‘Film Portrait of Mysterious Evangelist Night Writer’, The Age, 4 April 1995, p. 20.

Barbara Creed, ‘Ghost Who Walked the City Streets’, The Age, 23 March 1995, p. 20.

Trish FitzSimons, Pat Laughren & Dugald Williamson, Australian Documentary: History, Practices and Genres, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011.

John Hughes, ‘Life or the Transience of Existence: Director Lawrence Johnston Interviewed by John Hughes’, Cinema Papers, no. 112, October 1996, pp. 6–9.

Sarah Swain, ‘Exclusive: Legendary Sydney Figure “Mr Eternity” Brought Back to Life’, 9News, 11 June 2019, <https://www.9news.com.au/national/sydney-film-festival-mr-eternity-arthur-stace-film/7abef3eb-11c2-4d44-bcbf-15d2e30aee8c>.

David Tiley, ‘Eternity 24 Times a Second to Stop the Passage of Time’, Screenhub, 9 October 2019, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2019/10/09/eternity-24-times-a-second-to-stop-the-passage-of-time-258974/>.

David Tiley, ‘Long Tail: An Object Lesson in the Reach for Eternal Sales’, Screenhub, 25 July 2014, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2014/07/25/long-tail-an-object-lesson-in-the-reach-for-eternal-sales-244946/>.

MAIN CAST

Arthur Stace Les Foxcroft Radio Announcer Gordon Weiss Young Colin Anderson Neil Jordan Young George Gittoes Angus Benfield

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1994 Length 56 minutes Director Lawrence Johnston Production Company Vivid Pictures Producer Susan MacKinnon Cinematographer Dion Beebe Editor Annette Davey Art Director Tony Campbell Sound Recordist Paul Finlay Sound Designer Liam Egan Composer Ross Edwards

Endnotes

| 1 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Dreaming in Motion: Celebrating Australia’s Indigenous Filmmakers, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 2007, p. 40, available at <https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Dreaming-in-Motion.pdf>, accessed 30 August 2021 |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on the notion of documentary voice, see Bill Nichols, ‘The Voice of Documentary’, Film Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, Spring 1983, pp. 17–30. |

| 3 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in David Tiley, ‘Eternity 24 Times a Second to Stop the Passage of Time’, Screenhub, 9 October 2019, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2019/10/09/eternity-24-times-a-second-to-stop-the-passage-of-time-258974/>, accessed 30 August 2021. |

| 4 | For a thoughtful discussion on collaborative documentary, see Leah Anderst, ‘Memory’s Chorus: Stories We Tell and Sarah Polley’s Theory of Autobiography’, Senses of Cinema, issue 69, December 2013, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/memorys-chorus-stories-we-tell-and-sarah-polleys-theory-of-autobiography>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 5 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Pauline Adamek, ‘Eternity – A Filmic Tribute to a Sydney Ghost by Lawrence Johnston’, ArtsBeatLA, 20 January 2013, <http://www.artsbeatla.com/2013/01/eternity/>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 6 | See Remo Giuffré, ‘Eternity’, REMO General Store website, 21 July 2020, <https://remogeneralstore.com/blogs/news/eternity>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 7 | Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Pamela Beere Briggs, ‘Talking Heads: Eternity’s Lawrence Johnston and Susan MacKinnon’, International Documentary, vol. 14, no. 1, February 1995, available at <https://www.documentary.org/feature/talking-heads-eternitys-lawrence-johnston-and-susan-mackinnon>, accessed 2 September 2021. |

| 8 | Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Trish FitzSimons, Pat Laughren & Dugald Williamson, Australian Documentary: History, Practices and Genres, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011, p. 101. |

| 9 | Peter Sainsbury, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., p. 134. |

| 10 | MacKinnon, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., p. 101. |

| 11 | Tim Read, quoted in FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, ibid., pp. 134–5. |

| 12 | Briggs, op. cit. |

| 13 | FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, op. cit., p. 101. |

| 14 | David Tiley, ‘Long Tail: An Object Lesson in the Reach for Eternal Sales’, Screenhub, 25 July 2014, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2014/07/25/long-tail-an-object-lesson-in-the-reach-for-eternal-sales-244946/>, accessed 2 September 2021. |

| 15 | Barbara Creed, ‘Ghost Who Walked the City Streets’, The Age, 23 March 1995, p. 20. |

| 16 | Peter Crayford, ‘Shorts Long on Variety’, The Australian Financial Review, 16 June 1995, p. 18. |

| 17 | See Tiley, ‘Long Tail’, op. cit. |

| 18 | Susan MacKinnon, quoted in Tiley, ibid. |

| 19 | Chris Arneil, ‘New Restoration Premieres at Sydney Film Festival’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 7 June 2019, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/nfsa-restores-eternity-premiere-sydney-film-festival>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 20 | Roy Williams with Elizabeth Meyers, Mr Eternity: The Story of Arthur Stace, Acorn Press, Sydney, 2017. |

| 21 | FitzSimons, Laughren & Williamson, op. cit., p. 135. |

| 22 | Werner Herzog, ‘Minnesota Declaration’, 30 April 1999, available at <https://www.wernerherzog.com/complete-works-text.html#2>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 23 | ‘It’s not an ordinary story, and I think that’s the reason people go to see movies: […] to see extraordinary stories.’ Lawrence Johnston, in ‘Eternity: Lawrence Johnston Interview’, The Movie Show, 1994, available at <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/11676227585/eternity-lawrence-johnston-interview>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 24 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit. |

| 25 | Nichols, op. cit., p. 18. |

| 26 | An audio recording of John Ridley’s sermon can be downloaded from SermonIndex.net at <https://www.sermonindex.net/modules/mydownloads/viewcat.php?cid=629>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 27 | She describes Stace’s ‘Eternity’ as ‘a sermon he was writing in the streets’. |

| 28 | Greg Burchall, ‘Film Portrait of Mysterious Evangelist Night Writer’, The Age, 4 April 1995, p. 20. |

| 29 | Johnston, quoted in Adamek, op. cit. |

| 30 | Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit. |

| 31 | John Hughes, ‘Life or the Transience of Existence: Director Lawrence Johnston Interviewed by John Hughes’, Cinema Papers, no. 112, October 1996, p. 9. |

| 32 | Johnston, quoted in Briggs, op. cit. |

| 33 | Briggs, ibid. |

| 34 | Roland Barthes describes the photograph as ‘a figuration of the motionless and made-up face through which we see the dead’. Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Cape, London, 1982, p. 32. |

| 35 | Briggs, op. cit. |

| 36 | Creed, op. cit. |

| 37 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Tracey Korsten, ‘Feeling the Glow: Lawrence Johnston’s Neon’, Glam Adelaide, 24 August 2016, <https://glamadelaide.com.au/feeling-the-glow-lawrence-johnstons-neon/>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 38 | A recording of Ravlich’s program is available at <http://mpegmedia.abc.net.au/innovation/sidetracks/sydney_content/mp3/eternity/eternity_mobile.mp3>, accessed 5 September 2021. |

| 39 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Sarah Swain, ‘Exclusive: Legendary Sydney Figure “Mr Eternity” Brought Back to Life’, 9News, 11 June 2019, <https://www.9news.com.au/national/sydney-film-festival-mr-eternity-arthur-stace-film/7abef3eb-11c2-4d44-bcbf-15d2e30aee8c>, accessed 11 July 2021. |

| 40 | Lawrence Johnston, quoted in Burchall, op. cit. |

| 41 | Briggs, op. cit. |

| 42 | ibid. |

| 43 | Burchall, op. cit. |

| 44 | See ‘Ross Edwards: Symphony no. 1 Da Pacem Domine (1991)’, ABC Classic, 14 December 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/classic/read-and-watch/classic-australia/ross-edwards-symphony-no-1-1991/10619828>, accessed 11 July 2021. |