Largely absent from Australia’s cinema boom of the 1970s were representations of contemporary urban society. Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975); Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975); Newsfront (Phillip Noyce, 1978); The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Fred Schepisi, 1978); My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979): the most memorable features of the time – and, for that matter, the ones most people remember today – were handsomely shot period films that took audiences back to the frontier years of the mid-nineteenth through to the mid-twentieth century, with narratives most often played out in the nation’s enigmatic outback zone. There were various dissenting examples, including films of the so-called ocker and Ozploitation genres. But, for the most part, the lives and trials of people living in modern-day urban Australia were limited to a few quietly-played-out affairs somewhere within the vague category of what Tom O’Regan calls ‘the lower-budgeted, modestly-promoted […] art-house film’.[1]Tom O’Regan, ‘The Enchantment with Cinema: Film in the 1980s’, in Albert Moran & O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1989, pp. 118–46. One of the few examples of such films made in Australia in the 1970s was Esben Storm’s 27A (1974).

On the face of things, there did not seem to be too much ordinariness on show in the 1980s either. That decade is now chiefly renowned for its blockbusters – movies like Gallipoli (Weir, 1981), Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986) and the Mad Max sequels[2]Mad Max 2 (George Miller, 1981) and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller, 1985). that took local cinema into the international arena. Yet this was also a period in which more filmmakers began to set their sights on reflecting back at us the intricacies of the commonplace, especially regarding the everyday lives of those on the metaphorical fringes of Australia’s burgeoning metropolitan areas. Although many of these films are sadly disregarded today – some never even made available in the DVD format – they can be seen as crucial forerunners to the successful naturalistic dramas of future directors such as Rowan Woods and Sarah Watt.

Two of the best cases in point are John Duigan’s Winter of Our Dreams (1981) and Paul Cox’s Lonely Hearts (1982).[3]Though both Winter of Our Dreams and Lonely Hearts have been released on DVD, they are not exactly easy to find today. In his book The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton describes how numerous worthy Australian films of the 1980s for various reasons faded into obscurity almost as soon as they were released. See Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990. This is not least because both stand as defining moments in the careers of filmmakers who had already shown evidence of their ability to represent contemporary Australia in smaller-scale films – Duigan with Mouth to Mouth (1978); Cox with Kostas (1979) – and were at the same time on the pathway to even greater achievements in the realm of the so-called personal film.[4]Duigan’s 1987 Australian Film Institute Awards Best Picture winner The Year My Voice Broke is regarded as one of the classic coming-of-age narratives in Australian cinema, while Cox’s Lonely Hearts, Man of Flowers (1983), My First Wife (1984) and Cactus (1986) surely form the finest quartet of consecutive films made by any Australian director.

Set in Sydney and Melbourne respectively, Winter of Our Dreams and Lonely Hearts are examples of a cinema that eschews violence, fantasy and/or historical verisimilitude, instead concentrating on important social themes (most notably, alienation) refracted through the drama of personal relationships and the minutiae of everyday lives. Yet they are, as each director has pointed out, not exclusively intimate films. In the former case, Duigan noted at the time that he saw Winter of Our Dreams as ‘no less political’ than his previous work, ‘though it operates in a different way’.[5]John Duigan, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘John Duigan and Winter of Our Dreams’, Cinema Papers, no. 33, July–August 1981, p. 228. Similarly, Cox has argued that all of his films ‘deal with the human condition’, and that ‘to do that is a great political act’.[6]Paul Cox, quoted in Richard Phillips, ‘An Interview with Paul Cox, Director of Innocence: “Filmmakers Have a Duty to Speak Out Against the Injustices in the World”’, World Socialist Web Site, 6 January 2001, <https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2001/01/pcox-j06.html>, accessed 4 August 2021.

Distant lives: Winter of Our Dreams

At the beginning of the 1980s, Australia was a nation in transition, the activism of the Vietnam War era and the hope for change induced by the Whitlam government having been largely usurped by a familiar patriarchal conservatism that set itself against ‘threats to the Australian way of life’.[7]As stated by David Kemp, a senior adviser to the Fraser government, in Quadrant in 1977. Cited in Richard White, Inventing Australia, Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1981, pp. 164–5. It is against this backdrop that Winter of Our Dreams’ Rob (Bryan Brown) and Lou (Judy Davis) negotiate their lives in a decaying yet characterful inner Sydney prior to the gentrification of the 1990s and beyond.

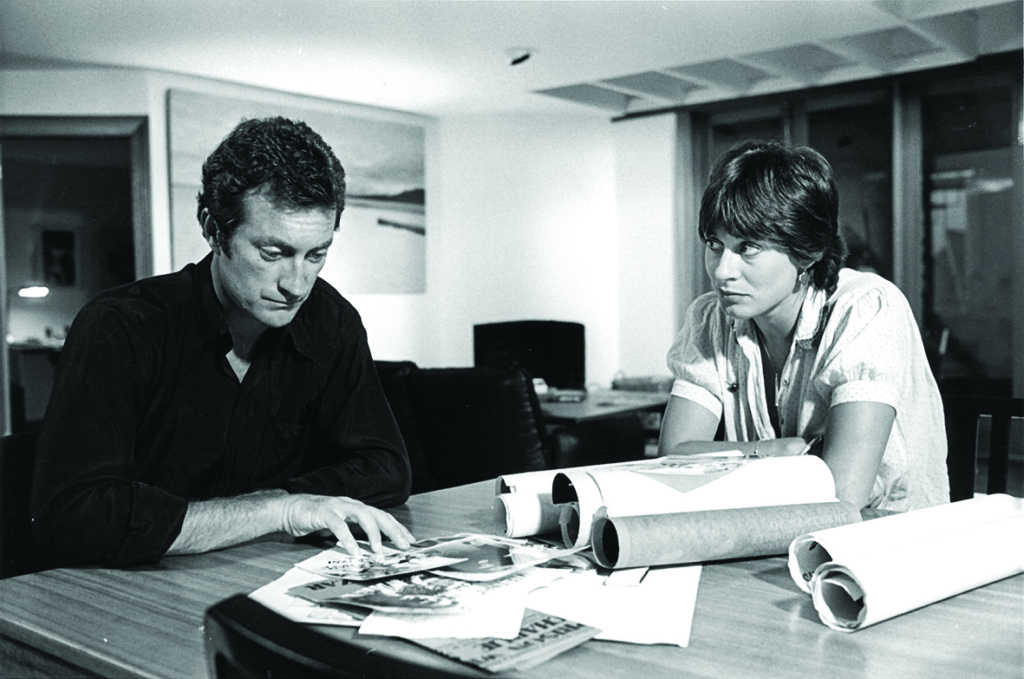

Laconic Kings Cross bookstore owner Rob clings rather tenuously to his political past: he maintains an open relationship with his partner Gretel (Cathy Downes), an academic; they live in a swish Balmain house, though Rob still plays for the local Trotskyites’ soccer team. His life seems mired in a detached defeatism, more stimulated by combat with a computerised chess opponent than his wife’s sexual conquests. Lou, meanwhile, seems intrigued by Rob’s radicalism, but is for now trapped in a web of homelessness, sex work and heroin addiction.

It is notable how pretty much everyone in Winter of Our Dreams sits on the sidelines, looking on at the world around them without doing much to alter it. Even the line of cops perpetually watching over a group of anti-uranium protesters maintain their distance, seemingly not concerned with wading in to menace the crowd and verifying the sordid reputation of Sydney’s police circa the early 1980s. The only characters in the film who exude real warmth are the protesters themselves, who appear sporadically at the fringes of the narrative, eventually offering companionship to the increasingly lost and disillusioned Lou.

The Sydney of Winter of Our Dreams is largely shorn of that city’s iconic signifiers: while the harbour itself features briefly as a means of transport (via ferry), the Harbour Bridge, Opera House and newly built Centrepoint Tower are absent. This is the 1980s inner-urban Sydney that the travel brochures overlooked: a city that, as Delia Falconer puts it, ‘insists on eternal shadows dogging [its] beauty, on some principle of distortion’.[8]Delia Falconer, Sydney, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, p. 52. It is also the real heart of the metropolis: the backstreets, alleyways and other in-between spaces where day-to-day stories of isolation and anxiety, grief and melancholy play out.

In fact, Winter of Our Dreams is awash with a general melancholy. The blue, washed-out tones of the film are evocative of such feelings. Lou, in particular, is at a loss in her own life. In her fragility, loneliness and inability to have much agency due to drug addiction and poverty, there is a profound sense of her living at the edge of society – never quite belonging anywhere or to anyone. This makes her burgeoning bond with Rob particularly poignant, as he is comfortably middle-class, so much so that he seems to run his bookstore more as a hobby than a job. Rob’s life is largely buffered from the cold, harsh street life of Kings Cross in which Lou must eke out her existence.

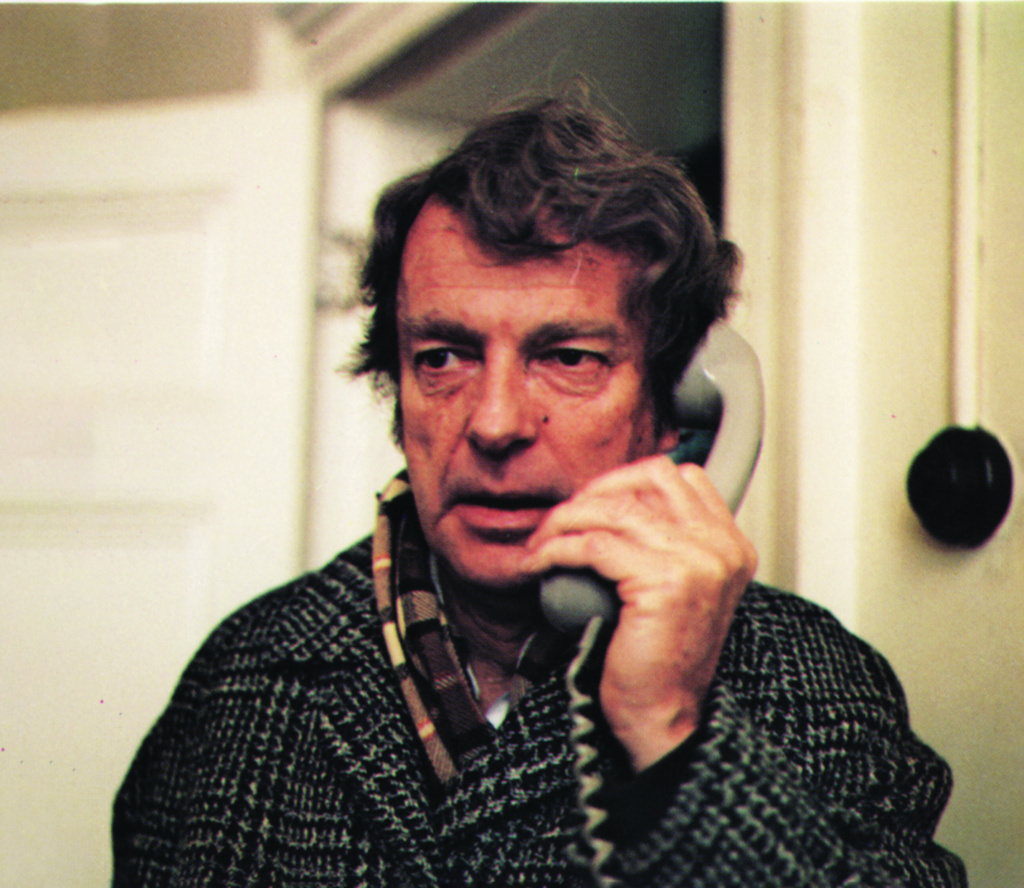

Missed connections and squandered opportunities haunt the film – indeed, it is bookended by them. At the outset, a young woman, who we later learn is Rob’s ex-girlfriend Lisa (Margie McCrae), tries to connect with him by ringing from a public telephone – possibly a last-ditch attempt to seek support before taking her own life – only for him to miss her call by seconds. Likewise, near the conclusion of the film, after Lou has weaned herself off heroin and invites Rob over for lunch, he cancels at the last minute, choosing instead to play in a soccer game.

Davis’ performance as Lou is unforgettable: she exposes the audience to the knife edge of her fragile identity, one drenched in an inconsolable loneliness. The profundity of her sense of abandonment brings to the fore the importance of human relationships and how they largely determine the quality of one’s life. In the end, Lou’s vulnerability and anguish – conveyed through a close-up of her face – leaves us pondering whether she, like Lisa before her, is teetering on the edge of citified oblivion.

Sex and sensitivity: Lonely Hearts

If Duigan’s film unlocked the door to true-to-life drama set at the fringes of suburbia circa 1981, Lonely Hearts, filmed approximately six months later in the depths of the Victorian winter, pushed it wide open.[9]Despite its title, Winter of Our Dreams was shot in the summer of 1980–1981. See ‘Winter of Our Dreams’, OzMovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/winter-of-our-dreams>, accessed 5 August 2021. The first – along with Man of Flowers and My First Wife – of an inner Melbourne–based trilogy from the director, Lonely Hearts affirmed Cox’s position as one of the most gifted local filmmakers of the period.

The first – along with Man of Flowers and My First Wife – of an inner Melbourne–based trilogy from the director, Lonely Hearts affirmed Cox’s position as one of the most gifted local filmmakers of the period.

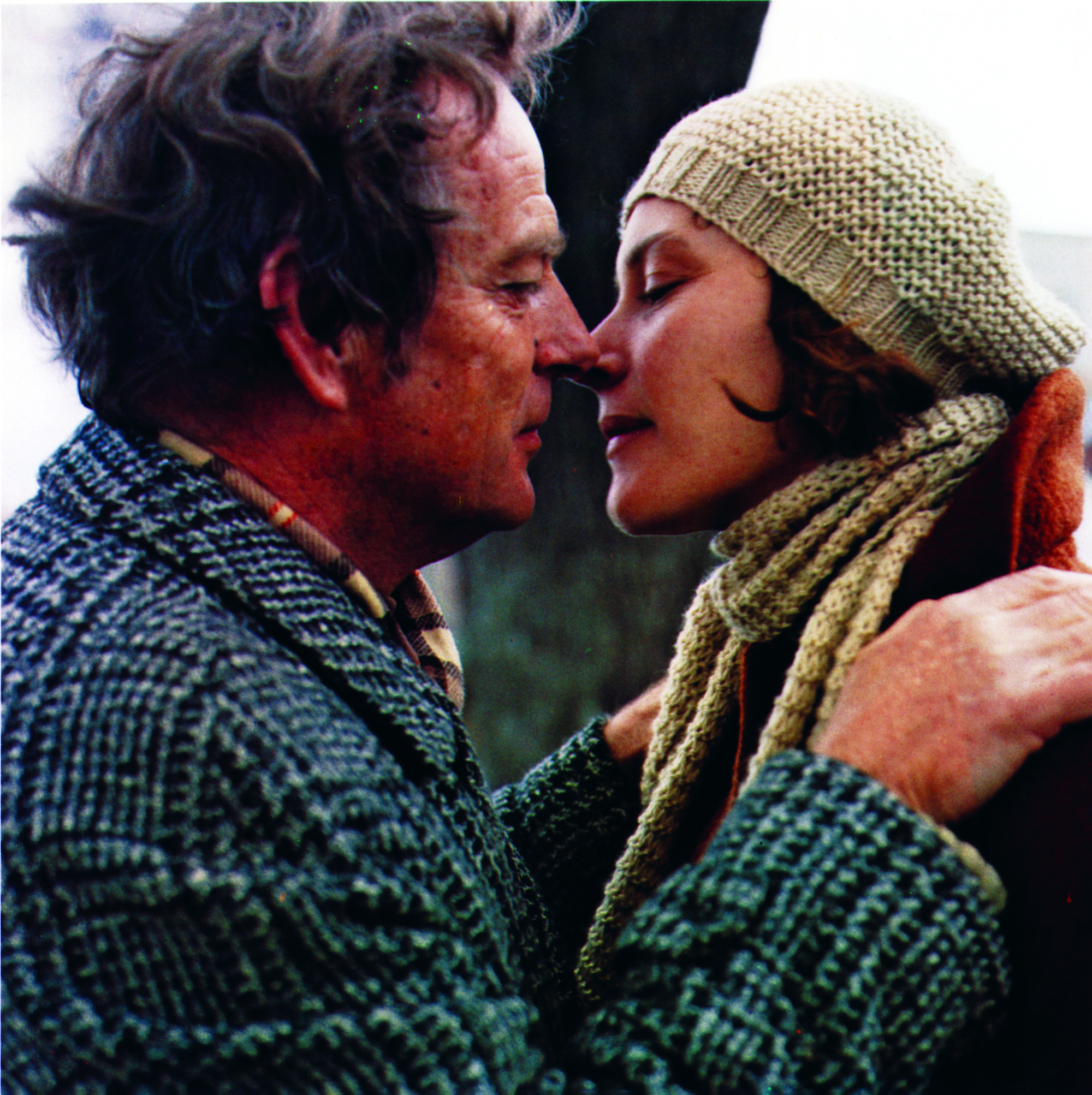

The film follows Patricia (Wendy Hughes) and Peter (Norman Kaye) as they embark on an awkward, fitful courtship after meeting through a dating agency. The film’s sexual tension juxtaposes Peter’s likeable awkwardness with Patricia’s at-times-excruciating sexual inexperience. Through the latter’s therapy sessions, we learn about her anxieties around intimacy. This has the effect of infusing every encounter she has with Peter with a degree of apprehension.

One is able to surmise that Patricia’s decision to live alone in a one-bedroom apartment has been a first, tentative, courageous move towards independence from her elderly, smothering parents, whose sole purpose in life seems to be to keep their daughter festooned in cotton wool. The regularity of her parents’ phone calls enquiring into her whereabouts when she is not at home, as well as their hostility towards her involvement in an amateur theatre company, reveals the high level of control they seek to exert over her. Yet while Peter comes across as having the upper hand in the intimacy stakes in this tentative setting, he is mostly browbeaten in life (especially by his bossy sister Pamela, played by another Cox regular, Julia Blake).

Secrets infuse Peter’s character in Lonely Hearts, providing the film with a degree of pathos. For instance, he conceals from Patricia the fact that he wears a toupee and is an occasional kleptomaniac. Also, he is not incapable of being playfully deceptive, such as when he pretends to be a blind piano tuner, only for his client to then witness him get into a car and drive off. It is these small details that give his character a degree of humanity and levity. Patricia, on the other hand, cannot help but display her self-consciousness – until, in the end, the veneer finally cracks and she turns on her suffocating parents (with the aid of stage director George, played by Jon Finlayson, who adds a further humorous note to proceedings).

Cox doubtless carefully chose August Strindberg’s 1887 theatrical work The Father to be the play-within-a-film in Lonely Hearts, foregrounding as it does the efforts of a married couple to control the future life and career of their daughter. In his analysis of the film in Metro, Neil Sinyard argues that Patricia’s commitment to performing in the play is unpersuasive since it contradicts her personality; while he acknowledges that such a pursuit could be seen as an attempt to escape from the self, he asserts that the notion is not adequately explored in the film.[10]See Neil Sinyard, ‘Lonely Hearts’, Metro, no. 178, Spring 2013, p. 85. Regardless, the stage-production narrative serves as an effective plot device that enables a second level of storytelling to emerge among the play’s clumsy amateur cast, revealing Lonely Hearts once more to be a film deeply sensitive to the fine detail of human experience.

When juxtaposed with Winter of Our Dreams, it is tempting to see Lonely Hearts – with its rigidly lower-middle-class suburban setting and happy(ish) ending – as steeped in conservative values. Patricia and Peter operate within a vastly different social world from Rob and Lou: a dimly lit, largely unadventurous world of workaday jobs (bank clerk; piano tuner) and proper cultural interests (Strindberg on the stage, classical music on the stereo). On the face of it, Winter of Our Dreams is a rock concert to Lonely Hearts’ tea party.

Yet despite his penchant for the middlebrow end of the highbrow world, Cox as a director is one of the great radicals of the everyday. Though a generation removed from Duigan – Cox was born in 1940, within the so-called ‘silent generation’, while Duigan, born in 1949, is a confirmed boomer – his gaze is similarly focused on society’s outsiders. While Cox’s Patricia and Peter might not be as openly daring in aesthetics and relationships as Duigan’s Rob and Lou, the complexity and dignity of their portrayal nonetheless situates Cox alongside Duigan as an artist who specialises in shining a light on what we might term ‘commonplace defiances’.

Closer to home: Existentialist cinema

Winter of Our Dreams and Lonely Hearts focus on commonplace human relationships and interactions, much as it might be said that Duigan and Cox are for the most part directors who take human interaction as their primary subject matter. Thus Lisa’s suicide in Winter of Our Dreams and the death of Peter’s mother in Lonely Hearts – critical life events alluded to at the beginning of the respective films – quickly recede into the background, in order for more routine concerns of life and love to take over. In the early 1980s, these were archetypal ‘arthouse’ works, low-key and largely destined for short runs in specialist theatres (though Lonely Hearts was a minor hit in the US).

Today, however, the ‘arthouse’ descriptor seems less applicable to this style of film, particularly as it has been popularly used to categorise such diverse (and starkly different) works as The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970), A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971), Being John Malkovich (Spike Jonze, 1999), Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001) and The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009). So when Adrian Martin asks if Cox’s films could endure comparison with the oeuvres of an Andrei Tarkovsky or a Béla Tarr,[11]Adrian Martin, ‘Ozploitation Compared to What? A Challenge to Contemporary Australian Film Studies’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, 2010, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 9–21. While Martin’s wider point is well taken in terms of the cult/avant-garde focus of these various filmmakers, it is not so clear where one could begin in measuring Cox’s minimal, uniquely Australian style up against the epic sweep of Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979) or Werckmeister Harmonies (Tarr, 2000) – nor is it clear why one would want to do so. the question is perhaps beside the point. Both Winter of Our Dreams and Lonely Hearts, arising out of a specific cultural moment in Australian film (and Australian life more generally), might bear better comparison to examples of the various alternative Australian music scenes of the early 1980s. For instance, think of how homespun, lo-fi productions like The Go-Betweens’ 1983 song ‘Cattle and Cane’ or The Triffids’ 1986 album In the Pines belatedly received international recognition; or of how musicians from the early 1980s Melbourne experimental scene – Warren Burt, David Chesworth, Philip Brophy and others – were adding their own unique sounds to that period’s global ‘thoroughgoing critique of rock music and its received wisdoms’.[12]Jon Dale, ‘Once upon a Time in Melbourne’, Wire, October 2006, issue 272, pp. 32–7. In a similar way, these two striking yet intimate films can remain outside of unseemly attempts to position them in any hierarchy of greatness. Instead, they stand alongside Breaker Morant (Bruce Beresford, 1980), Careful, He Might Hear You (Carl Schultz, 1983) and other better known features as valuable contributions to both the local and international cinema of the early 1980s.

Where they are strikingly different from other local and international examples is their style. Though the term ‘personal film’ has been applied,[13]Les Rabinowicz has said that ‘within the film industry [Cox is] often described as the “champion of the personal film”’. Rabinowicz, ‘Australian Film Industry Profile: Paul Cox’, Metro, no. 66, 1985, p. 16. Likewise, in his study of Winter of Our Dreams, Neil Rattigan calls it ‘a personal film with a sense of commitment’. Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, TX, p. 322. a more appropriate label may be ‘existentialist cinema’. This is because these are films that focus on the human condition and the nature of individual experience: quite simply, they attempt to ‘show us […] how people live’.[14]William Pamerleau, Existentialist Cinema, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 2. It’s true that Picnic at Hanging Rock and Breaker Morant also do that to some extent; almost any movie does. But the plot in those films is driven by a crisis of some kind – the children going missing in the former case; the court martial of the accused murderers in the latter – and they are also greatly impinged upon by the historical or period nature of their narratives and by the way each is presented (through cinematography, editing, sound design and so forth).

The goals of Duigan’s Winter of Our Dreams and Cox’s Lonely Hearts seem far more modest. Yet despite their intimate focus, neither film can be underestimated for the power of their insight into the human condition more generally (in particular, the universal need for companionship). And while this might seem trifling, the personal is political in the sense that it is about navigating the difficult and messy spheres of human emotion and ethics that bleed into – and, in fact, become a microcosm of – the wider spectrum of public/political connections, in which principles of trust and ethical interpersonal behaviour are crucial. In short, both films show us how to live in the world.

Endnotes

| 1 | Tom O’Regan, ‘The Enchantment with Cinema: Film in the 1980s’, in Albert Moran & O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1989, pp. 118–46. One of the few examples of such films made in Australia in the 1970s was Esben Storm’s 27A (1974). |

|---|---|

| 2 | Mad Max 2 (George Miller, 1981) and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller, 1985). |

| 3 | Though both Winter of Our Dreams and Lonely Hearts have been released on DVD, they are not exactly easy to find today. In his book The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton describes how numerous worthy Australian films of the 1980s for various reasons faded into obscurity almost as soon as they were released. See Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990. |

| 4 | Duigan’s 1987 Australian Film Institute Awards Best Picture winner The Year My Voice Broke is regarded as one of the classic coming-of-age narratives in Australian cinema, while Cox’s Lonely Hearts, Man of Flowers (1983), My First Wife (1984) and Cactus (1986) surely form the finest quartet of consecutive films made by any Australian director. |

| 5 | John Duigan, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘John Duigan and Winter of Our Dreams’, Cinema Papers, no. 33, July–August 1981, p. 228. |

| 6 | Paul Cox, quoted in Richard Phillips, ‘An Interview with Paul Cox, Director of Innocence: “Filmmakers Have a Duty to Speak Out Against the Injustices in the World”’, World Socialist Web Site, 6 January 2001, <https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2001/01/pcox-j06.html>, accessed 4 August 2021. |

| 7 | As stated by David Kemp, a senior adviser to the Fraser government, in Quadrant in 1977. Cited in Richard White, Inventing Australia, Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1981, pp. 164–5. |

| 8 | Delia Falconer, Sydney, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, p. 52. |

| 9 | Despite its title, Winter of Our Dreams was shot in the summer of 1980–1981. See ‘Winter of Our Dreams’, OzMovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/winter-of-our-dreams>, accessed 5 August 2021. |

| 10 | See Neil Sinyard, ‘Lonely Hearts’, Metro, no. 178, Spring 2013, p. 85. |

| 11 | Adrian Martin, ‘Ozploitation Compared to What? A Challenge to Contemporary Australian Film Studies’, Studies in Australasian Cinema, 2010, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 9–21. While Martin’s wider point is well taken in terms of the cult/avant-garde focus of these various filmmakers, it is not so clear where one could begin in measuring Cox’s minimal, uniquely Australian style up against the epic sweep of Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979) or Werckmeister Harmonies (Tarr, 2000) – nor is it clear why one would want to do so. |

| 12 | Jon Dale, ‘Once upon a Time in Melbourne’, Wire, October 2006, issue 272, pp. 32–7. |

| 13 | Les Rabinowicz has said that ‘within the film industry [Cox is] often described as the “champion of the personal film”’. Rabinowicz, ‘Australian Film Industry Profile: Paul Cox’, Metro, no. 66, 1985, p. 16. Likewise, in his study of Winter of Our Dreams, Neil Rattigan calls it ‘a personal film with a sense of commitment’. Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, TX, p. 322. |

| 14 | William Pamerleau, Existentialist Cinema, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 2. |