As the Australian film revival of the 1970s flowed into its second decade, several local films benefited from the attention given to antipodean cinema, resulting in critical and commercial success. Released in 1983, Carl Schultz’s drama Careful He Might Hear You, based on Sumner Locke Elliott’s 1963 novel of the same name,[1]While the title of Elliott’s book is Careful, He Might Hear You, the comma was omitted in the film version (albeit retained in some publicity material). was initially met with healthy box office, some amount of critical praise and thirteen Australian Film Institute Award nominations (going on to win eight, including Best Picture). Yet whenever this prolific period of Australian filmmaking is rediscovered and re-examined, Schultz’s film is rarely part of the conversation. Despite its virtues, Careful He Might Hear You is somewhat underappreciated, even ignored – an observation that its producer, Jill Robb, made unequivocally in 2007: ‘I do think that [the film] has been substantially forgotten.’[2]Jill Robb, in the featurette A Child’s Journey from the Page to the Screen: The Making of Careful He Might Hear You, Careful He Might Hear You, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2007.

This unjust erasure is rather surprising given that, as a period piece adapted from an acclaimed literary source, Careful He Might Hear You was following the successful template of many of the still highly regarded Australian films that preceded it. Such works – including Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975), The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Fred Schepisi, 1978) and My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979) – were collectively described by critic Keith Connolly as portraying ‘a distinctive national flavor, most obvious in their rich visual texture’ and ‘combining an awesome natural beauty with high drama’.[3]Keith Connolly, ‘The Proud “New Wave” of Films from Australia’, The New York Times, 15 February 1981, Section 2, p. 1, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1981/02/15/movies/australia-s-pride-is-it-s-new-wave-of-films.html>, accessed 14 February 2022. Film historian Graeme Turner discussed these techniques in further detail, noting a preponderance in the Australian cinema of the period of

films set in the past, foregrounding their Australianness through the re-creation of history and representations of the landscape; lyrically and beautifully shot; and employing aesthetic mannerisms such as a fondness for long, atmospheric shots, an avoidance of action or sustained conflict and the use of slow motion to infer significance.[4]Graeme Turner, ‘Art Directing History: The Period Film’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin, Melbourne, 1989, p. 100. Brian McFarlane notes in his examination of the phenomenon that ‘there was perhaps a sense that some of the respectability of the literary genre would rub off on the film versions’, which ‘were rather consciously aimed at more discerning filmgoers, and as more or less art-house movies’. McFarlane, ‘The Film of the Book: Adaptation and the Australian Cinema’, Metro, no. 149, 2006, pp. 54–5.

Schultz’s film fits all of these classifications in a visual sense: it’s nothing if not rich, lyrical and atmospheric, and captures the geography of Sydney beautifully. It also hews closely to its source text; Michael Jenkins’ screenplay is faithful to the point of being reverential to Elliott’s Miles Franklin Literary Award winner, a barely disguised autobiography that sold 10 million copies internationally.[5]See Brendan Doyle, ‘A Life of Separation from the Ordinary’, Green Left, 17 July 1996, <https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/life-separation-ordinary>, accessed 14 February 2022.

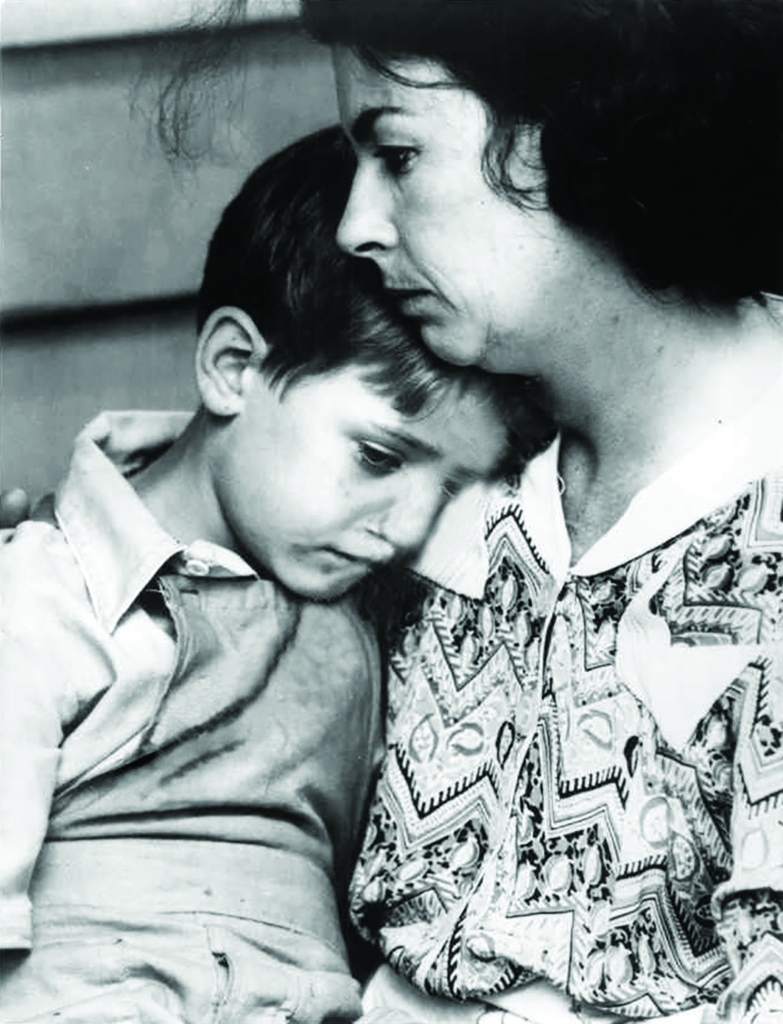

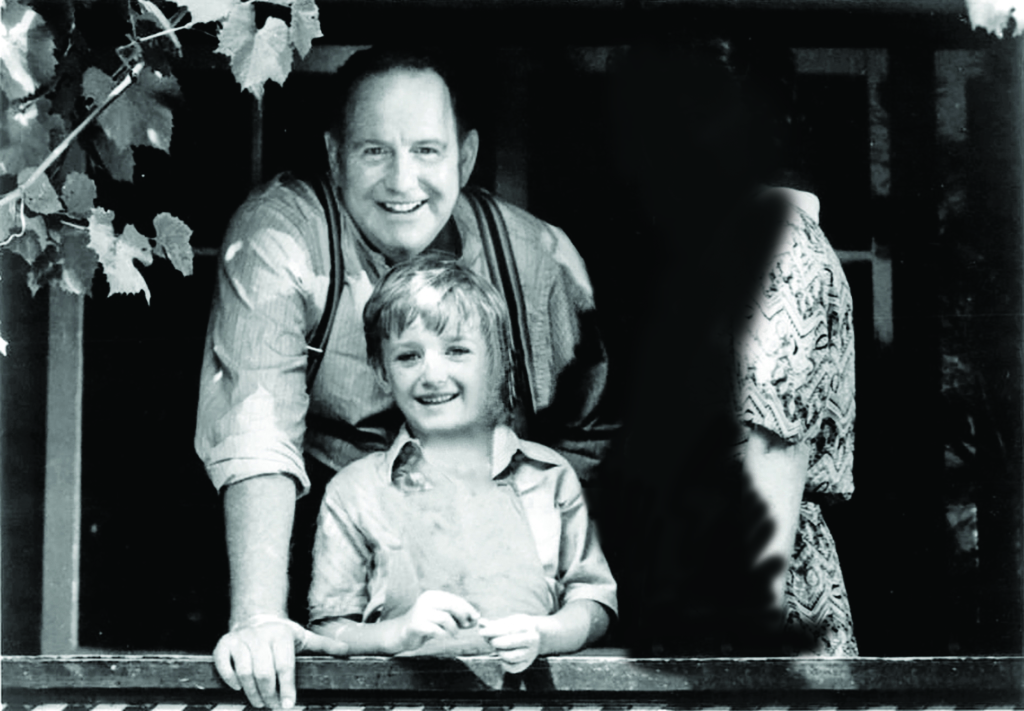

Set in Sydney during the 1930s, Schultz’s film opens with a tight close-up of a young boy’s eyes as he lies in bed overhearing an adult conversation. Orphaned from birth, PS (Nicholas Gledhill) lives with his aunt Lila (Robyn Nevin) and uncle George (Peter Whitford), but his late mother’s presence still looms: the family refers to her, deity-like, as ‘Dear One’; while ‘PS’ is the nickname she bestowed on her son before she passed away, describing him as ‘a postscript to her ridiculous life’. The subject of the night-time discussion he is listening to is the return from Europe of his aunt Vanessa (Wendy Hughes), whom he has never met, but who will, upon her arrival in Sydney, insist on sharing in his guardianship. This shift in circumstances uproots PS from his life with Lila and George, placing him at the centre of an unsettling psychological – and, at times, quite literal – tug of war.

Living with a wealthy elderly cousin in a mansion complete with servants and birds in elaborate gilded cages, Vanessa is proper to the point of being rigid and repressed. Despite her initial promises to not ‘upset the rhythm of his life’, she pulls an unwilling PS into her refined world with a tenacity that borders on smothering. His torment is exacerbated by a humiliating initiation at his new private school, where he is forced to take his trousers down and endure a whipping at the hands of a female classmate.

When PS’ alcoholic father, Logan (John Hargreaves), turns up, Vanessa attempts to curry favour with him in the hope he will sign over full custody. In a moment of desperation and perhaps manipulation, she begs of him, ‘Love me.’ He rejects her, disappearing as quickly as he emerged.

As the relationship between the aunts becomes increasingly adversarial, the case eventually ends up in the Supreme Court of New South Wales, which awards full custody to Vanessa after the judge mistakenly infers that PS has been coached by Lila. Devastated by the decision, PS withdraws from Vanessa, reciting pleases and thank yous in unfeeling monotone and seeming to derive a sinister pleasure from finding ways to torment her. Defeated, she finally relinquishes control, sending him back to Lila and George. ‘It seems I’ve finally done something to please you,’ she tells him during their final goodbye. ‘Now everybody’s going to get what they want.’ Vanessa’s gilded cages are open at last, setting the stage for her eventual death in a ferry accident on Sydney Harbour.

Style and substance

Despite featuring a male protagonist, Careful He Might Hear You shares many qualities with the ‘women’s pictures’ of Hollywood’s Golden Age, particularly in its depiction of Vanessa. In her exhaustive study A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930–1960, film historian Jeanine Basinger sees through the soap-opera conceits of the genre, arguing that, at their core, such films ‘tell the truth […] because they are about the unhappiness of women’ and ‘tell all the lies in the world to make that one point clear’.[6]Jeanine Basinger, A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930–1960, Knopf Doubleday, New York, 2013 [1993], p. 7. Accordingly, throughout Careful He Might Hear You, Vanessa’s unhappiness is palpable but never articulated; as unhappy as she is, her unwillingness to have her wishes denied spreads her misery to all those around her. This refusal to be marginalised serves as both impetus and tragic downfall for Vanessa, and again links Schultz’s film with its classical predecessors; as Basinger puts it, ‘The woman’s film accomplishes one important thing for its viewers: it puts the woman at the center of the universe.’[7]ibid., p. 15.

When the film was initially optioned for a US adaptation in the 1960s, Elliott wanted his friend Vivien Leigh cast as Vanessa[8]Sharon Clarke, ‘Sumner Locke Elliott: Writing Life’, PhD thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, 1995, p. 213, fn. 21. (Elizabeth Taylor was also considered for the role before the American production was shelved[9]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Careful He Might Hear You (1983)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/careful-he-might-hear-you/notes/>, accessed 14 February 2022.). In the hands of a Hollywood diva, the role of Vanessa could have verged on overly theatrical or camp; Hughes, by contrast, mostly manages to keep the character grounded, although there is a sparkle of grandiosity in her performance. In one scene, she coolly chastises her sister, ‘I don’t know why you’re being so dramatic about this,’ as she delectably draws a whirlwind of drama into everyone’s lives.

Hughes’ first scene sees her framed in silhouette, backlit with a halo-like outline, exquisitely adorned by one of Bruce Finlayson’s period costumes as she caresses an ornate cigarette holder. She plants a kiss on a motionless PS, the pair framed in a tight close-up more familiar to intimate love scenes. ‘Well well, PS – at last,’ she sighs. Like the female stars of yesteryear, Hughes owns the screen, menacing and alluring in equal measure.

Finlayson’s costuming is only one piece in Schultz’s sumptuous and sensual re-creation of an Australia that was already long gone by 1983. This plush visual sensibility is skilfully rendered by director of photography John Seale (who would use Careful He Might Hear You as a springboard for a successful, Oscar-winning Hollywood career in cinematography); he perfectly captures the unique Australian light, along with the tension in the air brought about by the conflicting passions and desires of the characters.

Not all of the film’s elements are quite so meticulously handled, however. Careful He Might Hear You occasionally teeters towards melodrama, a tendency reinforced by the intense and at times intrusive strings from Ray Cook’s score that threaten to swamp the film’s more delicate dramatic moments. According to critic David Stratton, the director later regretted that he ‘never had time to modify the score which, on a couple of occasions, underlines what is already on screen far too insistently’.[10]David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan MacMillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 183.

Wrestling with identity

The melodrama is underpinned by Schultz’s representation of Australia’s Depression-era class divide, symbolically represented by the harbour separating Vanessa’s Elizabeth Bay mansion from Lila’s humbler, working-class cottage in Neutral Bay. The family drama serves as a microcosm of broader class warfare, as if the soul of the nation is at stake. Indeed, set at a time when many white Australians saw themselves as British subjects, the film, like the book,[11]Infamously cantankerous Australian author Patrick White showered the novel with praise on its release, writing in a letter to Elliott: ‘What a relief to read a novel about people of flesh and blood […] And you have brought it out so beautifully, both in atmosphere and place, tone of voice, and the characters, above all the characters …’ White, quoted in Clarke, op. cit., p. 420. in many ways depicts the birth of a new national identity – albeit one that is still somewhat elusive and contested nearly forty years later,[12]See Jill Sheppard & Nicholas Biddle, ‘Class, Capital, and Identity in Australian Society’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 52, no. 4, 2017, pp. 500–16. with ugly and classist perspectives never far from the surface.[13]For an example of such rhetoric, see Pru Goward, ‘Why You Shouldn’t Underestimate the Underclass’, The Australian Financial Review, 19 October 2021, <https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/don-t-underestimate-the-underclass-20211018-p5910c>, accessed 3 March 2022. Schultz’s success in capturing the social and cultural conflicts of Elliott’s novel could be attributed to his being an émigré from Hungary, which gave him a safe distance from which to see Australia for all its idiosyncrasies.

The melodrama is underpinned by Schultz’s representation of Australia’s Depression-era class divide, symbolically represented by the harbour separating Vanessa’s Elizabeth Bay mansion from Lila’s humbler, working-class cottage in Neutral Bay.

Vanessa’s attempts to turn PS into an Anglophile – sending him to a stuffy school where a stern teacher mocks his broad Aussie accent: ‘You’re at a nice private school now, and we always keep our vowels nice and open’ – are ultimately unsuccessful. She also attempts to teach him appropriate dining etiquette, saying, ‘Only tradespeople tuck their napkins into their collar’; she insists on riding lessons and punishing piano practice with a torturous metronome. When PS returns for visits to his aunt and uncle, he does so in a hearse-like chauffeur-driven car, leading a perplexed Lila to comment that ‘he comes back a little bit changed’. Her fears are realised when PS calls a young playmate ‘common’ and sparks a neighbourhood conflict.

This Pygmalionesque conditioning serves to emasculate PS – a fate worse than death in a machismo-obsessed culture – leading Logan to chide Vanessa, ‘What are you trying to do, turn him into a little sissy?’ In another scene, horrified to learn that the boy is taking dancing classes, Logan screams at her, ‘You’re turning him into a bloody poof!’ A queer reading of the film could interpret PS as being both obsessed with and repulsed by Vanessa, this glamorous, exotic and perplexing new presence in his life. Yet, to forge his own identity, he must sever this attachment and assert himself. ‘I’m not going back [to Vanessa],’ he declares to both aunts. ‘I decided myself.’ In a fit of rage, he destroys Vanessa’s bathroom along with all its feminine accoutrements, leaving a plume of powders and perfumes.

Despite Vanessa’s attempts to turn PS into a proper gentleman, all she inadvertently achieves is infantilising him. Schultz’s film renders him perpetually prepubescent, reinforced by the high camera angles from which he is seen and even a reference Vanessa makes to Peter Pan. He nonetheless manages to make sense of this adult world, seeing and hearing all, rendering the title of the film redundant. As such, the film is an agonising depiction of a child being cruelly bandied about, as deft and compelling as custody drama Kramer vs. Kramer (Robert Benton, 1979).

In her study of Elliott’s life, Sharon Clarke observed that, like his literary counterpart, the author felt a

sense of alienation and difference from other children […] Not being the ‘same’ he had therefore become ‘other’. As a child, he had awkwardly resigned himself to the part of the ‘outsider’ which he seemed destined to play.[14]Clarke, op. cit., pp. 12–3.

Vanessa’s final piece of advice to PS is to ‘find out who you are and you’ll find out how to love someone’. Elliott himself was circumspect about his sexuality until well into his seventies. His final novel, Fairyland, published in 1990, a year before his death, focuses on a young gay man coming of age in 1930s Sydney. As the book is also considered to be autobiographical, it’s easy to see the new protagonist of Seaton Daly, orphaned and raised by relatives, as a fully grown PS.

The climax of Careful He Might Hear You sees PS finally assert his will and retaliate, tormenting Vanessa with a cruel game. He leads his schoolfriends in mocking his aunt’s unsuccessful attempts at seduction, hugging pillows and pleading, ‘Hold me, Logan!’ As a thunderstorm rages, PS makes chilling eye contact with Vanessa, smiling deviously as she teeters on the precipice of a nervous breakdown. In these scenes, he embodies the qualities of other demonic children from cinema, such as Damien (Harvey Stephens) in The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) or Rebecca Smart’s titular protagonist in Celia (Ann Turner, 1989).

Adding to this streak of horror are the film’s incestuous undertones. In an earlier scene, Vanessa, deathly afraid of thunderstorms, holds PS tightly as though a substitute lover, breathing heavily and moaning until the storm passes. Adopting the emotional blackmail of an abuser once morning breaks, she says, ‘I’d rather you didn’t mention to anyone about last night. Promise?’ – the latter more of a menacing threat than a question.

Despite this odd seesawing in tone between melodrama and horror, there is a perverse relish in how Vanessa’s climactic death is shown. Elliott gave the character a fiery death in the novel, and Schultz stages her demise as one of the more cinematic moments in the film. As her passenger ferry is engulfed by a large cruise liner, Vanessa is sent hurtling into the hereafter, her last moments framed underwater, surrounded by swirling debris. Elliott’s real-life aunt and nemesis, in contrast, died from a more anticlimactic heart ailment; as Clarke observes, while the author’s mother’s death ‘gave him physical life, so his aunt’s death gave him emotional and spiritual freedom, a catharsis’.[15]ibid., p. 143. In the final scene, PS is now able to reclaim his birth name, declaring to his family (and to the audience), ‘That’s who I am. I’m Bill.’

Reception and legacy

Schultz’s adaptation of Careful He Might Hear You was feted in the US, listed among the National Board of Review’s Top Ten Films of 1984. The film made A$2.4 million at the Australian box office[16]Film Victoria, ‘Australian Films at the Australian Box Office’, 2011, p. 10, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20140209075310/http://www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/967/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf>, accessed 17 February 2022. and a similar amount on the American arthouse circuit,[17]‘Careful, He Might Hear You’, Box Office Mojo, <https://www.boxofficemojo.com/release/rl1565033985/>, accessed 17 February 2022. something few Australian films manage to achieve four decades on. Despite this success and a premiere screening at the Venice Film Festival, the film surprisingly struggled to find a distributor in Europe.

While reviews were generally on the positive side at the time,[18]For a detailed summary, see ‘Key Details’, ‘Careful He Might Hear You’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/careful-he-might-hear-you#details>, accessed 17 February 2022. Schultz managed to appease at least one important critic. Elliott himself was overjoyed with the film, standing in line at a cinema in New York. ‘I wanted to call out: “This is my movie! This is my movie!”’[19]Sumner Locke Elliott, quoted in Clarke, ibid., p. 425. The novel was reissued by Text Classics in 2013, with a new preface written by Nevin. Elliott’s novel is now considered a modern Australian classic, ensconced proudly and justifiably in the literary canon. Equally deserving of reappraisal is Schultz’s film, another modern classic that reflects back to its homegrown audience how our country once was – and, perhaps, who we still are.

Endnotes

| 1 | While the title of Elliott’s book is Careful, He Might Hear You, the comma was omitted in the film version (albeit retained in some publicity material). |

|---|---|

| 2 | Jill Robb, in the featurette A Child’s Journey from the Page to the Screen: The Making of Careful He Might Hear You, Careful He Might Hear You, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2007. |

| 3 | Keith Connolly, ‘The Proud “New Wave” of Films from Australia’, The New York Times, 15 February 1981, Section 2, p. 1, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1981/02/15/movies/australia-s-pride-is-it-s-new-wave-of-films.html>, accessed 14 February 2022. |

| 4 | Graeme Turner, ‘Art Directing History: The Period Film’, in Albert Moran & Tom O’Regan (eds), The Australian Screen, Penguin, Melbourne, 1989, p. 100. Brian McFarlane notes in his examination of the phenomenon that ‘there was perhaps a sense that some of the respectability of the literary genre would rub off on the film versions’, which ‘were rather consciously aimed at more discerning filmgoers, and as more or less art-house movies’. McFarlane, ‘The Film of the Book: Adaptation and the Australian Cinema’, Metro, no. 149, 2006, pp. 54–5. |

| 5 | See Brendan Doyle, ‘A Life of Separation from the Ordinary’, Green Left, 17 July 1996, <https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/life-separation-ordinary>, accessed 14 February 2022. |

| 6 | Jeanine Basinger, A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930–1960, Knopf Doubleday, New York, 2013 [1993], p. 7. |

| 7 | ibid., p. 15. |

| 8 | Sharon Clarke, ‘Sumner Locke Elliott: Writing Life’, PhD thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, 1995, p. 213, fn. 21. |

| 9 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Careful He Might Hear You (1983)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/careful-he-might-hear-you/notes/>, accessed 14 February 2022. |

| 10 | David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan MacMillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 183. |

| 11 | Infamously cantankerous Australian author Patrick White showered the novel with praise on its release, writing in a letter to Elliott: ‘What a relief to read a novel about people of flesh and blood […] And you have brought it out so beautifully, both in atmosphere and place, tone of voice, and the characters, above all the characters …’ White, quoted in Clarke, op. cit., p. 420. |

| 12 | See Jill Sheppard & Nicholas Biddle, ‘Class, Capital, and Identity in Australian Society’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 52, no. 4, 2017, pp. 500–16. |

| 13 | For an example of such rhetoric, see Pru Goward, ‘Why You Shouldn’t Underestimate the Underclass’, The Australian Financial Review, 19 October 2021, <https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/don-t-underestimate-the-underclass-20211018-p5910c>, accessed 3 March 2022. |

| 14 | Clarke, op. cit., pp. 12–3. |

| 15 | ibid., p. 143. |

| 16 | Film Victoria, ‘Australian Films at the Australian Box Office’, 2011, p. 10, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20140209075310/http://www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/967/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf>, accessed 17 February 2022. |

| 17 | ‘Careful, He Might Hear You’, Box Office Mojo, <https://www.boxofficemojo.com/release/rl1565033985/>, accessed 17 February 2022. |

| 18 | For a detailed summary, see ‘Key Details’, ‘Careful He Might Hear You’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/careful-he-might-hear-you#details>, accessed 17 February 2022. |

| 19 | Sumner Locke Elliott, quoted in Clarke, ibid., p. 425. |