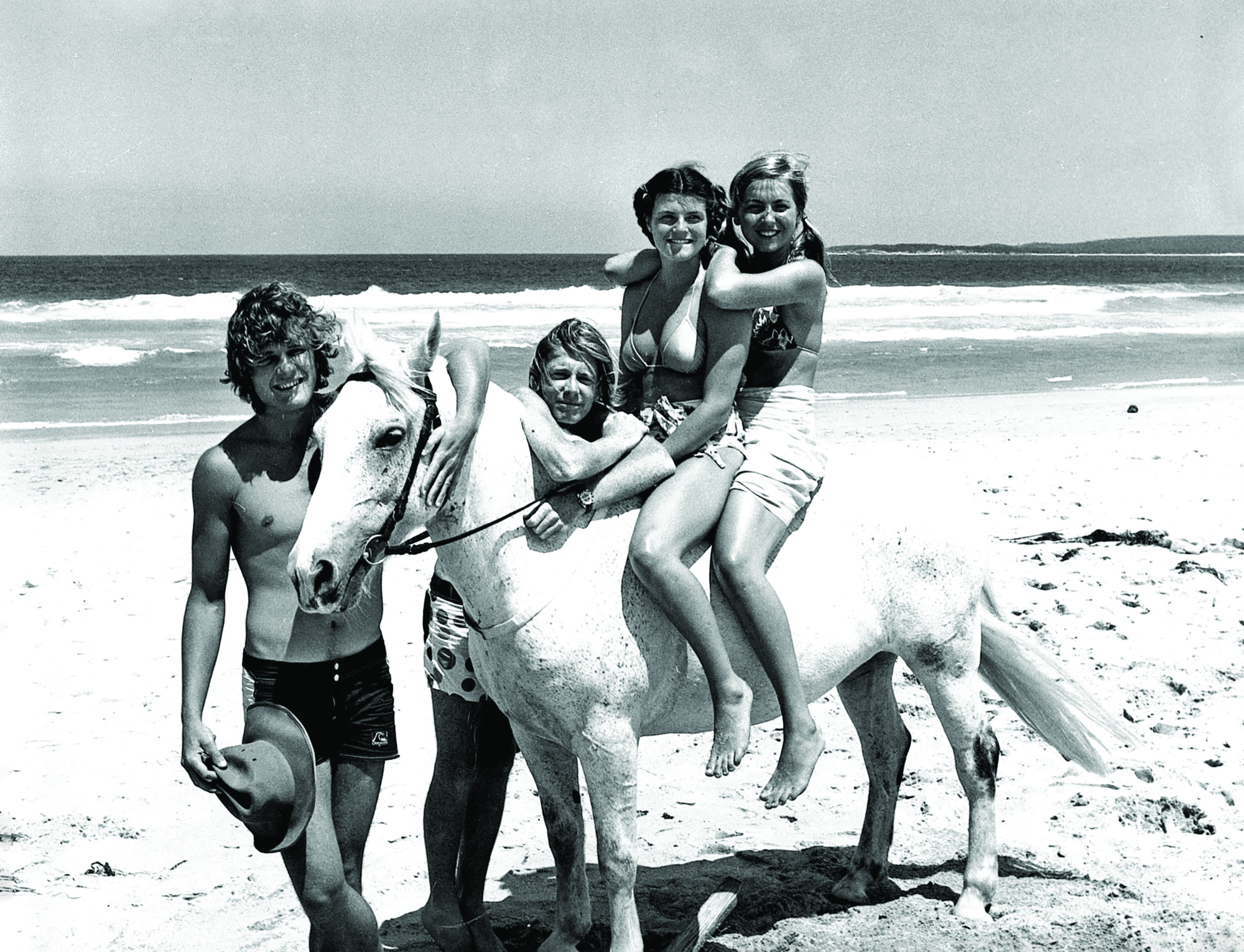

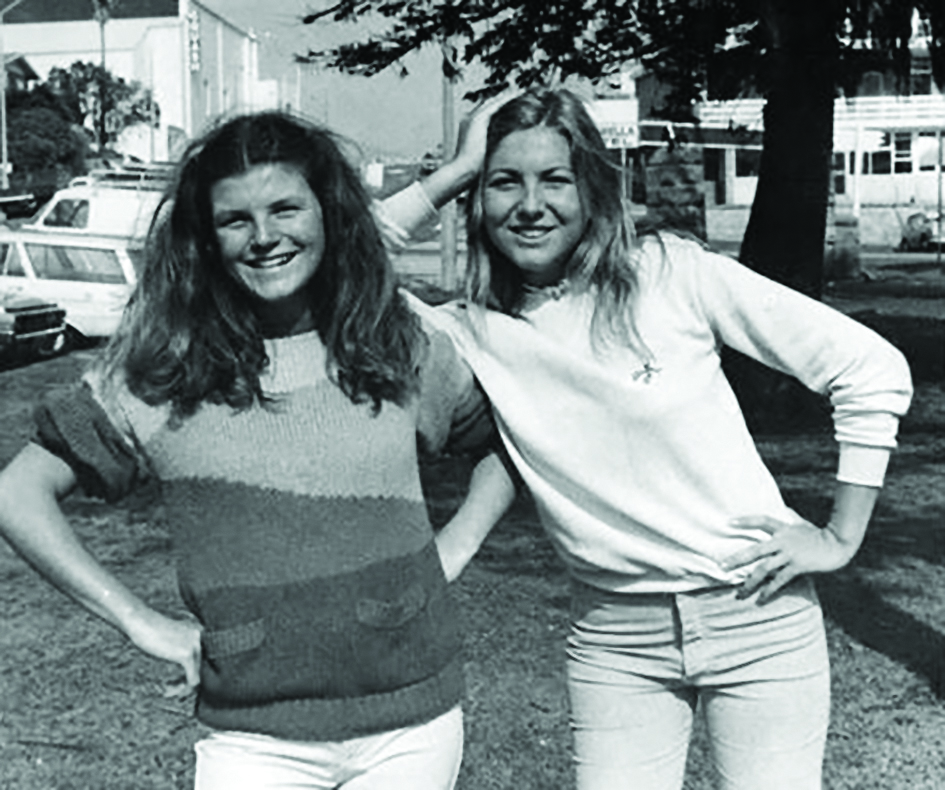

It is important that Puberty Blues (Bruce Beresford, 1981) ends with a freeze-frame. The film, which follows Sue Knight (Jad Capelja) and Debbie Vickers (Nell Schofield) as they navigate growing up in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire, gained infamy for its frank depiction of adolescence. Based on the classic novel of the same name by Gabrielle Carey and Kathy Lette, the film critiques the misogyny of surfie subculture during the 1970s; this critique is central to the film’s ending.

In what is, for critic Rose Capp, the film’s ‘defining moment’, Debbie and Sue grab a surfboard and head down to Cronulla beach for a surf, much to the surprise of their high school peers.[1]Rose Capp, ‘Chicks Don’t Surf: Puberty Blues (Bruce Beresford, 1981)’, Senses of Cinema, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2011/key-moments-in-australian-cinema-issue-70-march-2014/chicks-dont-surf-puberty-blues-bruce-beresford-1981/>, accessed 11 November 2021. This simple act challenges the chauvinistic maxim that ‘girls don’t surf’, repeated throughout the film and screamed by the boys watching on. It’s a moment of quiet rebellion, observed with admiration by the other girls sitting on the sand. But this is not where Puberty Blues ends. Soon after their surf, Debbie and Sue are standing atop a grassy bluff, basking in the glow of their victory. ‘I bet we’re dropped,’ Sue says with a smile, referring to the possibility of being dumped by her boyfriend, Danny (Tony Hughes). ‘Who cares?’ Debbie replies. ‘Yeah,’ comes Sue’s reply. ‘Who cares?’ The film freezes on this moment: two girls laughing on a sandy outcrop overlooking Cronulla beach. It’s a simple, joyous tableau. The credits roll.

What do we see in this canonical Australian film now, forty years since its premiere? How does the film, and the feminist critique it advanced, look back at us and contemporary Australia?

Four decades on, this ending remains an emblem for the Australian new wave, itself coming of age at the time. It also resembles that of another famous coming-of-age story ending with a freeze-frame, François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959). In this film, lead character Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) escapes a correctional facility for troubled youths to wander along a Normandy beach. With waves lapping at his feet, he turns to stare directly at the camera. This is where the film ends, with a close-up of Antoine’s expression frozen in place following an act of adolescent rebellion. Why does he look at us? What does he see? And what does this tell us about our role as spectators of the film? ‘At the end,’ wrote Arlene Croce of the scene in 1969, ‘you are no longer looking at the film – the film is looking at you.’[2]Arlene Croce, ‘The 400 Blows’, Film Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 3, Spring 1960, p. 38. This idea is equally helpful for understanding Puberty Blues. What do we see in this canonical Australian film now, forty years since its premiere? How does the film, and the feminist critique it advanced, look back at us and contemporary Australia? For a film that is interested in ways of looking and being observed, these questions offer a productive point from which to revisit its arguments – in other words, to ‘look’ back on an era of Chiko Rolls, endless Aussie summers and rusty panel vans and, in doing so, see contemporary Australia reflected back in a new light.

According to author Christos Tsiolkas, Beresford was ‘clearly influenced’ by the ‘spirit’ of The 400 Blows, ‘if not the film itself’.[3]Christos Tsiolkas, ‘Ladies in Black’, The Saturday Paper, 29 September 2018, available at <https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2018/09/29/ladies-black/15381432006919>, accessed 11 November 2021. Yet the view of Sydney’s sun-kissed Cronulla beach at the end of Puberty Blues is a far cry from the windblown coast of northern France. This contrasting setting also belies a tonal difference that separates both films. In The 400 Blows, a freeze-frame leaves audiences with an irresolvable anxiety for Antoine and his future. Puberty Blues, on the other hand, uses a similar beachside freeze-frame to instil a sense of hope for these girls and the future of the feminist rebellion they have just enacted. The continuation of their laughter on the soundtrack offers an extradiegetic promise that their victory against the sexism of their classmates will continue long after we’ve stopped watching them. They are not even looking at us, in the end, but at each other. If Antoine’s frozen gaze and the camera’s coinciding optically printed zoom bring the spectator into his bleak world, then the moment of camaraderie shared by Debbie and Sue places us on the outer, as observers.

This concluding attempt to position our viewership external to the girls is important. Throughout the film, it is Debbie and Sue who have been relegated to being spectators. They begin by observing the popular girls from their high school with envy. Once they gain entry into the ‘top surfie gang’, they are restricted to watching the boys surfing from the beach due to the sexist assumption that they are incapable of joining them. Debbie’s repeated suggestion, in contrast, that the group ‘go see a picture’ on a rainy day midway through the film seems an apt symbol: an example of spectatorship that does not relegate one to being a bystander. At least, in the context of a trip to the cinema, watching is an action that means one is included in the experience, rather than looking on from the outside.

Debbie and Sue grapple not only with the enforced passivity of their roles as spectators, but also with the prospect of being observed themselves. When they are looked at in the film, it is generally with derision, lust or indifference – all of which serve to objectify them. Often, such objectification is conducted in front of an audience of their peers. ‘Do I look all right?’ Debbie enquires after being told that a boy, Bruce (Jay Hackett), likes her. ‘Rootable,’ replies Tracey (Sandy Paul), prompting a chorus of laughter. Soon after, Debbie is making out with Bruce in front of a group of catcalling onlookers. The scene cuts between the kiss and mid-level close-ups of reactions from this leering crowd, emphasising how it is seen rather than how she experiences it. Debbie’s and Sue’s popularity, and their value as girls, is inextricably linked to how they are perceived; knowing this, they spend a majority of the film seeking ways to rise to, manipulate or cultivate this perception.

Debbie and Sue grapple not only with the enforced passivity of their roles as spectators, but also with the prospect of being observed themselves. When they are looked at in the film, it is generally with derision, lust or indifference.

It will come as no surprise to those who have worked with teenagers (or reflected on their own adolescence) to note the film’s interest in this experience of being observed. A presumption that one is under constant scrutiny is the quintessential adolescent experience, and often cause for self-consciousness and social anxiety. In 1967, child psychologist David Elkind introduced the term ‘imaginary audience’ in describing a period of adolescent development characterised by ‘continually constructing, or reacting to’ a feeling of being under surveillance.[4]David Elkind, ‘Egocentrism in Adolescence’, Child Development, vol. 38, no. 4, December 1967, p. 1030. How one reacts to this perceived surveillance, and the power it has to determine one’s behaviour, is inevitably informed by socially constructed ideas of what constitutes ‘normal’ behaviour – in other words, what behaviours might be denigrated or applauded by this imaginary audience. That these ideas of ‘normal’ are gendered – specifically, androcentric – is central to Puberty Blues’ critique.

This concept of coming of age being powerfully informed by an imaginary audience and the values one projects onto it is demonstrated by the male characters in the film. Besides Chiko Rolls, dumplings and sex, the boys require observation, specifically from girls. ‘You weren’t watching,’ Bruce complains to Debbie when he returns from having caught a ‘really good wave’; in his view, she has failed to do what is required of her. His and his mates’ actions consequently appear as a kind of performance that relegates the girls whom they’re ‘going round with’ to rapt members of an audience ready to applaud them. These boys make a spectacle of their masculinity and the privileges it affords them – most obviously, the capacity to surf – and require validation from onlookers to affirm their ability to make use of these privileges.

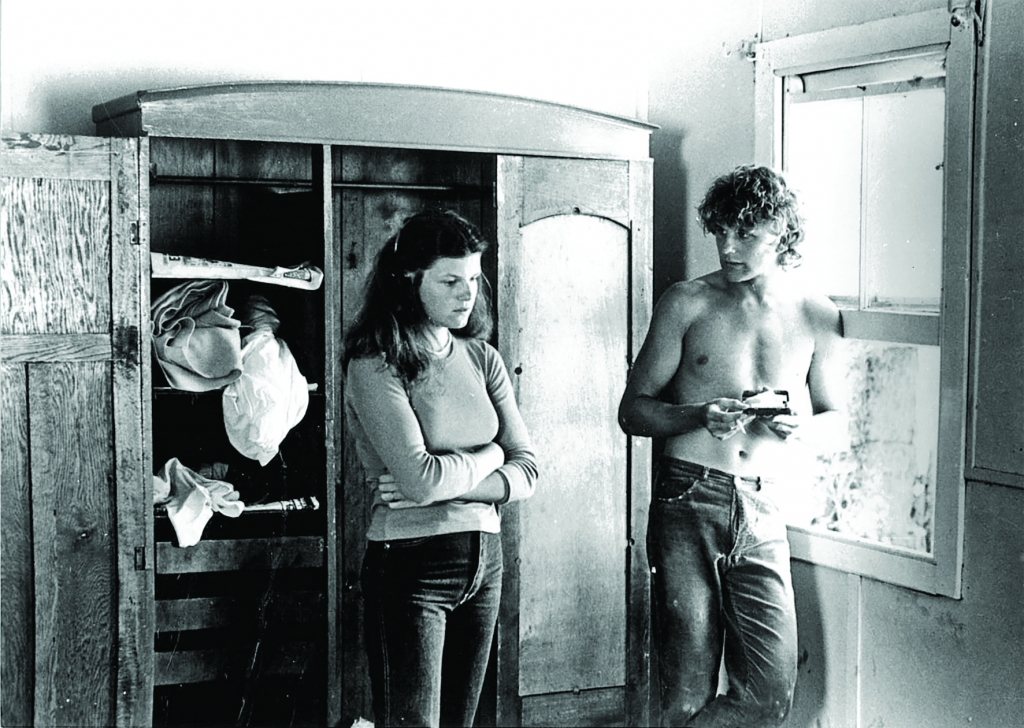

The insecurities implied by the value they attribute to being observed and the validation it affords is an idea explicitly toyed with throughout the film. In the back of Bruce’s much-admired panel van – decorated with bumper stickers with slogans such as ‘To all you virgins: thanks for nothing’ – Debbie sits, waiting for him to remove his clothes. Bruce quickly grabs his ‘toolbox’ to source a condom while Debbie, seemingly curious, watches him. Bruce soon catches her eye and returns her gaze with reproach, and she quickly looks away.

What causes Bruce’s reaction? Is it that Debbie caught him in a moment of physical vulnerability? On the surface, Debbie seems to be conforming to the spectator role previously required of her on the beach. While this scene is absent from Carey and Lette’s novel, there is a similar scene early on that proves helpful in understanding what is happening here. As they return from the surf, the boys begin to change out of their swimming costumes. In the process, they reveal their self-consciousness:

The ultimate disgrace for a surfie was to be seen in his scungies. They were too much like underpants. The boys didn’t want us checking out the size of their dicks.[5]Gabrielle Carey & Kathy Lette, Puberty Blues, Random House Australia, Melbourne, 2012 [1979], p. 8.

Bruce’s unsaid reprimand directed at Debbie is testament to this self-consciousness, particularly when being observed in a sexual context or in a sexual way. Here, Debbie’s watching has the capacity to disempower him; specifically, it has the potential to compromise his masculinity, or the performance of masculinity that he and the boys have showcased so successfully by surfing. The threat of disempowerment characterises the ‘imaginary audience’ Bruce projects onto Debbie’s curious gaze. His subsequent defensiveness masks an anger that, as the film subsequently shows us, carries with it the threat of violence. When Debbie throws a glass of beer at Strach (Ned Lander) during a party, the violence he threatens in response is contingent on Debbie’s action as much as by the fact that it occurred in front of an audience of his peers. For Debbie and Sue, coming of age in this deeply patriarchal setting – a subculture in which, as surfing scholar Jeff Lewis puts it, ‘hedonism, individualism and a transgressive and sexually unruly masculine spectacle’ were put on a pedestal[6]Jeff Lewis, ‘In Search of the Postmodern Surfer: Territory, Terror and Masculinity’, in James Skinner, Keith Gilbert & Allan Edwards, Some Like It Hot: The Beach as a Cultural Dimension, Meyer and Meyer Sport, Oxford, UK, 2003, p. 64. – means learning both how to be perceived and how to perceive, as well as the possibly violent repercussions for failing to enact what is learned.

Cultural studies scholar Tom O’Regan contends that Puberty Blues Others its Australian audience by asking them ‘to play anthropologist to their culture’.[7]Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 250. Our role as contemporary viewers is, academic Daniel Mudie Cunningham points out, one characterised by ‘anthropological “work”’ – a process heavily informed by the distance from which we study a subculture and time period different from our own.[8]Daniel Mudie Cunningham, ‘Puberty Blues’, Senses of Cinema, no. 33, October 2004, <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2004/cteq/puberty_blues/>, accessed 11 November 2021. The critical distance that such a role implies is surely bolstered by the nostalgia that characterised Puberty Blues initially, and, forty years later, much more acutely informs how we see it now. Yet what this anthropological mode of viewership ultimately reveals is the painful relevance of these themes today.

When Debbie and Sue dive into the water at the end of Puberty Blues, they become the observed, rather than the observers. The power of their final act of quiet rebellion is a result of them choosing to surf despite the chauvinistic taunts coming from the boys and girls on the beach. In ignoring them, they relegate their peers to the role of passive onlookers. Debbie and Sue do not conform to the rubric for ‘normal’ behaviour to which others seek to restrict them.

On 6 September 2021, Prime Minister Scott Morrison delivered a keynote address for the National Summit on Women’s Safety. His speech, which referred to the ‘serious failings in this very workplace, in this Parliament House’, was an implicit response to increased scrutiny of his government’s handling of – among other things – an allegation from former ministerial adviser Brittany Higgins that she had been raped by a fellow staffer.[9]Katina Curtis, ‘“Australia Has a Problem”, PM Tells Women’s Safety Summit’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/too-many-women-do-not-feel-safe-pm-20210906-p58p4w.html>, accessed 11 November 2021. Thousands of people watched the Prime Minister’s address, but many critiqued it as pure spectacle. ‘Words are meaningless without action,’ columnist Rachel Withers wrote;[10]Rachel Withers, ‘Talk Is Cheap’, The Monthly, 6 September 2021, <https://www.themonthly.com.au/today/rachel-withers/2021/06/2021/1630907813/talk-cheap>, accessed 11 November 2021. while Higgins observed that ‘platitudes and warm sentiments’ are insufficient.[11]Brittany Higgins, quoted in Curtis, op. cit. This audience was not imagined, nor was it capitulating to the placating intent some saw in Morrison’s speech. In other words, viewers were empowered by their refusal to remain bystanders and a desire to see the Prime Minister put the sentiments being expressed into practice. This was a kind of feminist reversal of the misogynistic perception depicted in Puberty Blues: behind the camera to which Morrison spoke was an audience looking back, creating their own rubric for what they needed to see his government do.

What is perhaps most affecting about Debbie and Sue’s defining moment at the end of Puberty Blues is the reaction it prompts in those watching from the sand. Extreme close-ups of reproachful boys are replaced by close-ups of bemused girls. As the scene continues, we see their facial expressions change from reproach to curiosity, and, finally, to joyous awe. In the background, a song written by New Zealand rock band Split Enz plays: ‘I don’t wanna suffer these conditions no more / Haven’t I the right to say / I don’t wanna suffer these conditions no more’. In finding a way to subvert the sexist culture surrounding them, Debbie and Sue exercise control over how they are perceived, forcing those watching to look inward and consider the sexism that informs their self-perception. It is a similar mode of self-critique that one wishes to provoke in our government today.

When Puberty Blues concludes with its freeze-frame, Debbie and Sue – unlike The 400 Blows’ young protagonist – are free from us as spectators, free from having to react to external forces of observation. The hopeful tone struck by this ending emerges from the implication that these two teenage girls continue laughing and talking long after our observation of them has stopped. They are able, one could imagine, to get a Chiko Roll unobserved, surf unobstructed and remain in their perpetual Aussie summer. Forty years on, it might be difficult to accept the optimistic future imagined by this simple ending. But if the ongoing response to the sexism that remains in Australia today tells us anything, it’s that – should we take a second to look for it – there is potential for change all around us.

Endnotes

| 1 | Rose Capp, ‘Chicks Don’t Surf: Puberty Blues (Bruce Beresford, 1981)’, Senses of Cinema, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2011/key-moments-in-australian-cinema-issue-70-march-2014/chicks-dont-surf-puberty-blues-bruce-beresford-1981/>, accessed 11 November 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Arlene Croce, ‘The 400 Blows’, Film Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 3, Spring 1960, p. 38. |

| 3 | Christos Tsiolkas, ‘Ladies in Black’, The Saturday Paper, 29 September 2018, available at <https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2018/09/29/ladies-black/15381432006919>, accessed 11 November 2021. |

| 4 | David Elkind, ‘Egocentrism in Adolescence’, Child Development, vol. 38, no. 4, December 1967, p. 1030. |

| 5 | Gabrielle Carey & Kathy Lette, Puberty Blues, Random House Australia, Melbourne, 2012 [1979], p. 8. |

| 6 | Jeff Lewis, ‘In Search of the Postmodern Surfer: Territory, Terror and Masculinity’, in James Skinner, Keith Gilbert & Allan Edwards, Some Like It Hot: The Beach as a Cultural Dimension, Meyer and Meyer Sport, Oxford, UK, 2003, p. 64. |

| 7 | Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 250. |

| 8 | Daniel Mudie Cunningham, ‘Puberty Blues’, Senses of Cinema, no. 33, October 2004, <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2004/cteq/puberty_blues/>, accessed 11 November 2021. |

| 9 | Katina Curtis, ‘“Australia Has a Problem”, PM Tells Women’s Safety Summit’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/too-many-women-do-not-feel-safe-pm-20210906-p58p4w.html>, accessed 11 November 2021. |

| 10 | Rachel Withers, ‘Talk Is Cheap’, The Monthly, 6 September 2021, <https://www.themonthly.com.au/today/rachel-withers/2021/06/2021/1630907813/talk-cheap>, accessed 11 November 2021. |

| 11 | Brittany Higgins, quoted in Curtis, op. cit. |